Low-Grade Fibromyxoid Sarcoma and Related Subtypes: A Systematic Review and Pooled Analysis of 773 Cases

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Study Design and Overview

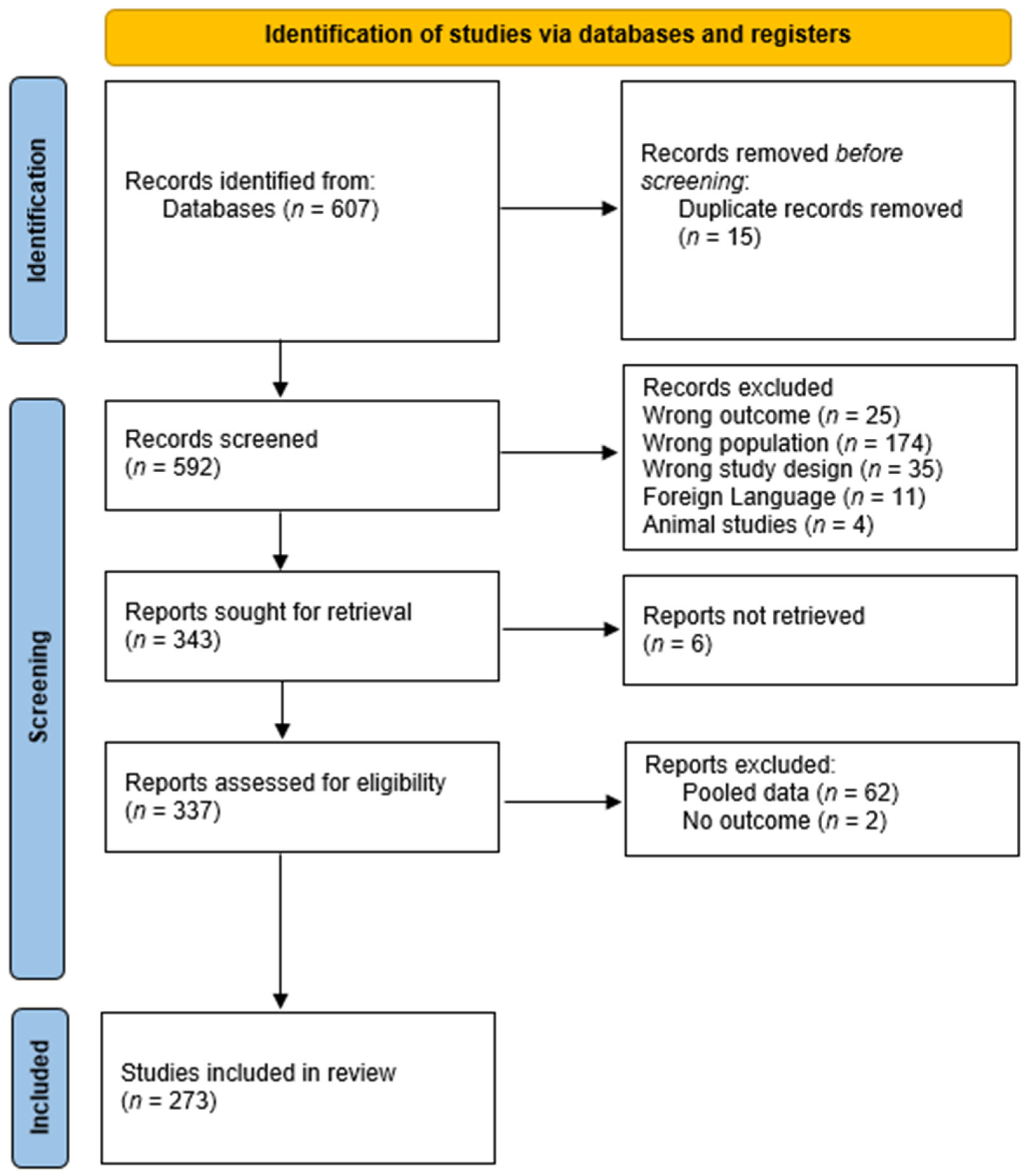

2.2. Search Strategy and Study Selection

2.3. Institutional Cases

2.4. Quality Assessment

2.5. Data Extraction and Synthesis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

3.2. Critical Appraisal

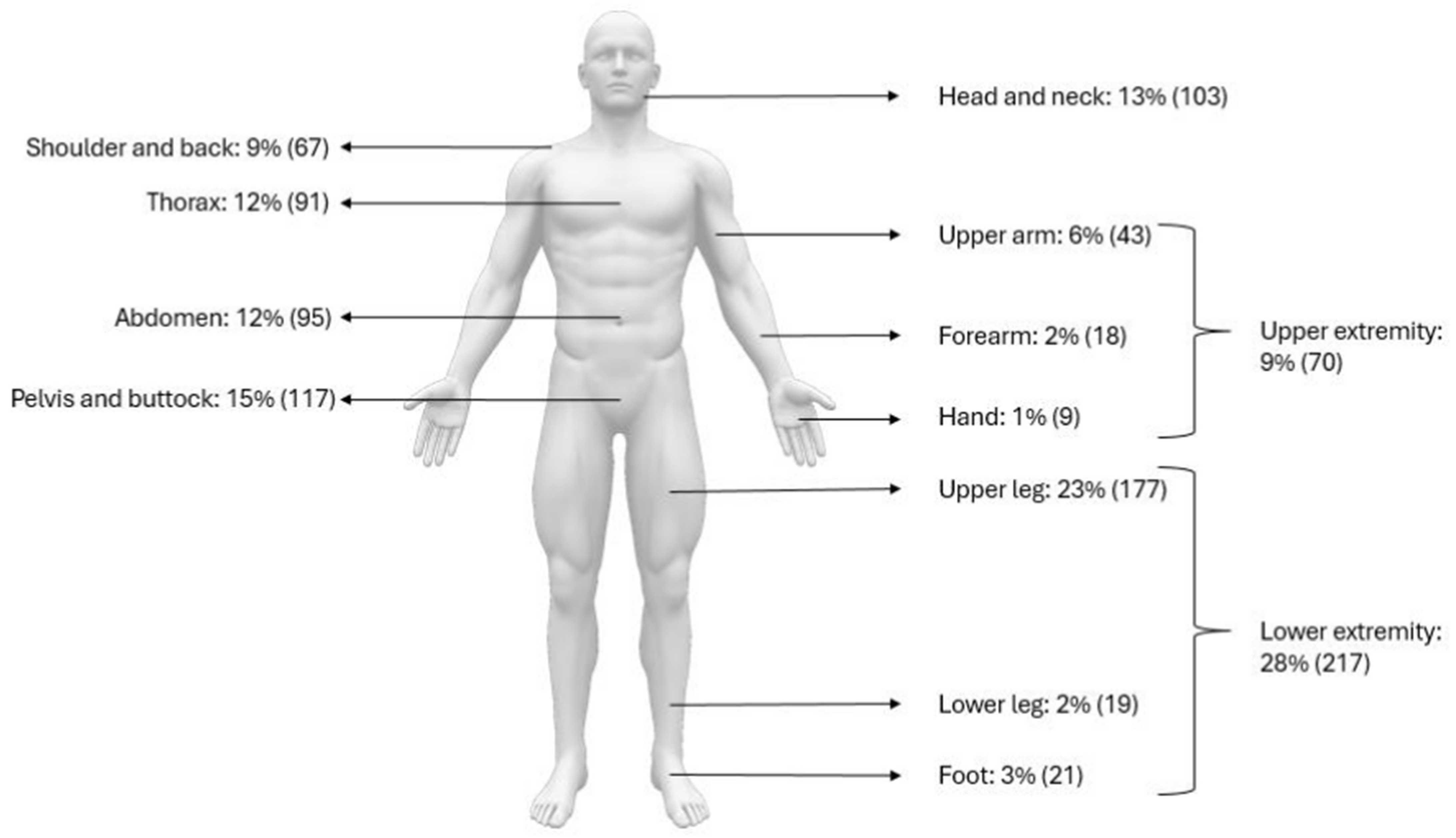

3.3. Patient Demographics and Tumor Distribution

3.4. Histopathology, Immunohistochemistry, and Cytogenetics

3.5. Clinical Presentation and Diagnostic Accuracy

3.6. Radiological Features

3.7. Treatment and Adjuvant Therapy

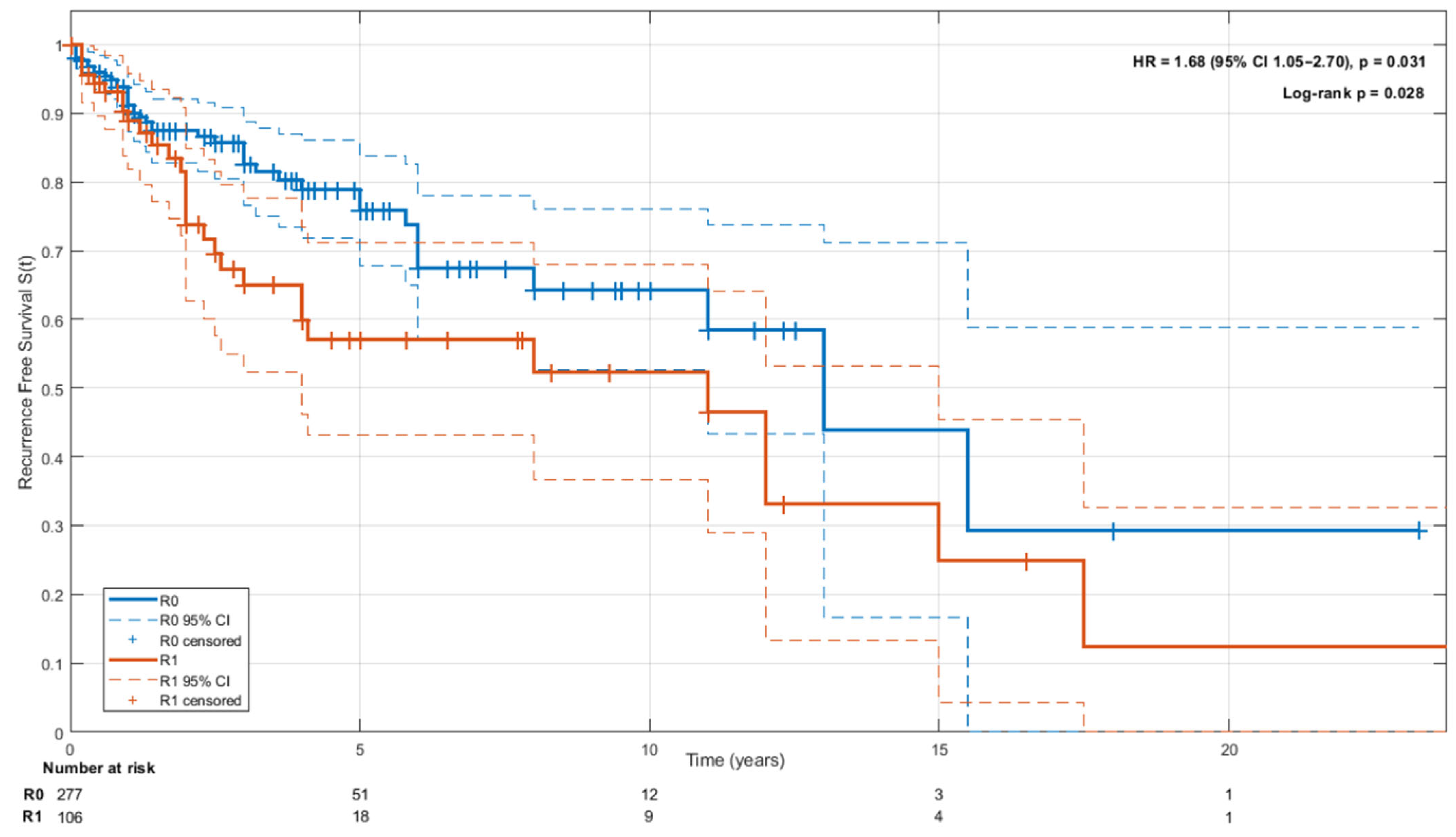

3.8. Oncological Outcomes and Follow-Up

4. Discussion

4.1. Diagnostic Challenges and Biopsy Technique

4.2. Histopathology and Cytogenetics

4.3. Surgical Management and Adjuvant Therapy

4.4. Oncological Outcomes and Prognosis

4.5. Study Limitations

4.6. Clinical Implications

5. Conclusions

Recommendations

- Diagnosis should rely on histology and molecular confirmation obtained through core-needle or open biopsy.

- Primary treatment is surgery with the aim of achieving R0 margins.

- Adjuvant therapies may be considered only within clinical trial settings or for unresectable/metastatic disease.

- Follow-up is advised, initially biannually MRI for five years, and then annually MRI up to 10 years, followed by careful patient education at discharge.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 95%-CI | 95% Confidence Interval | |

| AMC | Academic Medical Center | |

| AWD | Alive with disease | |

| CNB | Core needle biopsy | |

| CREB3L1/2 | Cyclic AMP responsive element-binding protein 3 like 1 and 2 | |

| CT | Computed Tomography | |

| DOD | Death of disease | |

| DOOD | Death of other disease | |

| DPIA | Data protection impact assessment | |

| EWSR1 | Ewing sarcoma RNA binding protein 1 | |

| FFPE | Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded | |

| FISH | Fluorescence in situ hybridization | |

| FNA | Fine needle aspiration | |

| FUS | Fused in sarcoma | |

| HSCTGR | Hyalinizing spindle cell tumor with grand rosettes | |

| IQR | Interquartile ranges | |

| LGFMS | Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma | |

| METC | Medical ethics review committee | |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging | |

| MUC4 | Mucin-related antigen 4 | |

| NCBI | National Center for Biotechnology Information | |

| NED | No evidence of disease | |

| PET | Positron Emissie Tomografie | |

| RT-PCR | Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction | |

| SEF | Sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma | |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences | |

| UFMS | Unclassified fibromyxoid sarcoma | |

| UMC | Amsterdam University Medical Centers | |

| UvA | University of Amsterdam | |

| WHO | World Health Organization | |

| WMO | Medical research involving human subjects act | |

References

- Tang, Z.; Zhou, Z.-H.; Lv, C.-T.; Qin, L.-Y.; Wang, Y.; Tian, G.; Luo, X.-L.; Zhu, Q.; Xu, X.-G. Low-Grade Fibromyxoid Sarcoma: Clinical Study and Case Report. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2010, 68, 873–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maretty-Nielsen, K.; Baerentzen, S.; Keller, J.; Dyrop, H.B.; Safwat, A. Low-Grade Fibromyxoid Sarcoma: Incidence, Treatment Strategy of Metastases, and Clinical Significance of the FUS Gene. Sarcoma 2013, 2013, 256280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Chapter 1 Soft Tissue Tumours. In Soft Tissue and Bone Tumours, 5th ed.; IARC: Lyon, France, 2020; p. 112. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, H.L. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma. A report of two metastasizing neoplasms having a deceptively benign appearance. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1987, 88, 615–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, K.L.; Shannon, R.J.; Weiss, S.W. Hyalinizing spindle cell tumor with giant rosettes: A distinctive tumor closely resembling low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1997, 21, 1481–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekhi, B.; Deshmukh, M.; Jambhekar, N.A. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma: A clinicopathologic study of 18 cases, including histopathologic relationship with sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma in a subset of cases. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 2011, 15, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storlazzi, C.T.; Mertens, F.; Nascimento, A.; Isaksson, M.; Wejde, J.; Brosjö, O.; Mandahl, N.; Panagopoulos, I. Fusion of the FUS and BBF2H7 genes in low grade fibromyxoid sarcoma. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003, 12, 2349–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov (accessed on 1 June 2018).

- GeneCards Human Gene Database. GeneCards—Human Genes. Genecards.Org. Available online: https://www.genecards.org/ (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Guillou, L.; Benhattar, J.; Gengler, C.; Gallagher, G.; Ranchère-Vince, D.; Collin, F.; Terrier, P.; Terrier-Lacombe, M.-J.; Leroux, A.; Marquès, B.; et al. Translocation-positive Low-grade Fibromyxoid Sarcoma: Clinicopathologic and Molecular Analysis of a Series Expanding the Morphologic Spectrum and Suggesting Potential Relationship to Sclerosing Epithelioid Fibrosarcoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2007, 31, 1387–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-Granada, C.; Zhang, L.; Chen, H.; Sung, Y.; Agaram, N.P.; Jungbluth, A.A.; Antonescu, C.R. A genetic dichotomy between pure sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma (SEF) and hybrid SEF/low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma: A pathologic and molecular study of 18 cases. Genes. Chromosom. Cancer 2014, 54, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisaoka, M.; Matsuyama, A.; Aoki, T.; Sakamoto, A.; Yokoyama, K. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma with prominent giant rosettes and heterotopic ossification. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2012, 208, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.K.C. Newly Available Antibodies With Practical Applications in Surgical Pathology. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 2013, 21, 553–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domanski, H.A.; Mertens, F.; Panagopoulos, I.; Åkerman, M. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma is difficult to diagnose by fine needle aspiration cytology: A cytomorphological study of eight cases. Cytopathology 2009, 20, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, S.; Kelliher, E.; Hameed, M. Imaging features of low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma (Evans tumor). Skelet. Radiol. 2012, 41, 1263–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, Y.; Liu, Y.; Song, L.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z. MRI findings of low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma: A case report and literature review. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2018, 19, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamberlain, F.; Engelmann, B.; Al-Muderis, O.; Messiou, C.; Thway, K.; Miah, A.; Zaidi, S.; Constantinidou, A.; Benson, C.; Gennatas, S.; et al. Low-grade Fibromyxoid Sarcoma: Treatment Outcomes and Efficacy of Chemotherapy. In Vivo 2019, 34, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canpolat, C.; Evans, H.L.; Corpron, C.; Andrassy, R.J.; Chan, K.; Eifel, P.; Elidemir, O.; Raney, B. Fibromyxoid sarcoma in a four-year-old child: Case report and review of the literature. Med. Pediatr. Oncol. 1996, 27, 561–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaud, L.; Schartz, N.E.; Bousquet, G.; Sarandi, F.; Verola, O.; Madelaine, I.; Kerob, D.; Lebbe, C. Transient Sunitinib-Induced Coma in a Patient With Fibromyxoid Sarcoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 1569–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenbroucke, J.P.; von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Pocock, S.J.; Poole, C.; Schlesselman, J.J.; Egger, M.; STROBE Initiative. Strengthening the Reporting of Ob-servational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and elaboration. Epidemiology 2007, 18, 805–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Barker, T.H.; Moola, S.; Tufanaru, C.; Stern, C.; McArthur, A.; Stephenson, M.; Aromataris, M. Methodological quality of case series studies: An in-troduction to the JBI critical appraisal tool. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2127–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Tufanaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Sears, K.; Sfetcu, R.; Currie, M.; Lisy, K.; Qureshi, R.; Mattis, P.; et al. Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In JBI Reviewer’s Manual; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, SA, Australia, 2020; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342598414_Chapter_7_Systematic_Reviews_of_Etiology_and_Risk (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Barker, T.H.; Hasanoff, S.; Aromataris, E.; Stone, J.C.; Leonardi-Bee, J.; Sears, K.; Habibi, N.; Klugar, M.; Tufanaru, C.; Moola, S.; et al. The revised JBI critical appraisal tool for the assessment of risk of bias for cohort studies. JBI Evid. Synth. 2024, 23, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermanek, P.; Wittekind, C. The Pathologist and the Residual Tumor (R) Classification. Pathol. Res. Pract. 1994, 190, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheer, M.; Vokuhl, C.; Veit-Friedrich, I.; Münter, M.; von Kalle, T.; Greulich, M.; Loff, S.; Stegmaier, S.; Sparber-Sauer, M.; Niggli, F.; et al. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma: A report of the Cooperative Weichteilsarkom Studiengruppe (CWS). Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2019, 67, e28009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gjeorgjievski, S.G.; Fritchie, K.; Thangaiah, J.J.; Folpe, A.L.; Din, N.U. Head and Neck Low-Grade Fibromyxoid Sarcoma: A Clinicopathologic Study of 15 Cases. Head Neck Pathol. 2021, 16, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geramizadeh, B.; Zare, Z.; Dehghanian, A.R.; Bolandparvaz, S.; Marzban, M. Huge mesenteric low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma: A case report and review of the literature. Rare Tumors 2018, 10, 2036361318777031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulay, K.; Rao, R.; Honavar, S.G.; Reddy, V.A.P. Primary orbital low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma—A case report. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 67, 568–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.M.; Du, W.; Mangano, W.E.; Mei, L. Mediastinal Low-Grade Fibromyxoid Sarcoma With FUS-CREB3L2 Gene Fusion. Cureus 2021, 13, e15606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.-J.; Park, W.-S.; Jin, J.-M.; Ha, C.-W.; Lee, S.-H. Low Grade Fibromyxoid Sarcoma in Thigh. Clin. Orthop. Surg. 2009, 1, 240–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wan, D.; Gao, F. Primary low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma of the breast: A rare case report with immunohistochemical and fluorescence in situ hybridization detection. Hum. Pathol. 2018, 79, 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, Y.; Pang, Y.H.; Sanjeev, J.S.; Kuick, C.H.; Chang, K.T.-E. Primary Renal Hybrid Low-grade Fibromyxoid Sarcoma-Sclerosing Epithelioid Fibrosarcoma: An Unusual Pediatric Case With EWSR1-CREB3L1 Fusion. Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. 2018, 21, 574–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, J.C.; Visa, A.; Zhang, L.; Antonescu, C.R.; Christison-Lagay, E.R.; Morotti, R. Primary Low-Grade Fibromyxoid Sarcoma of the Kidney in a Child with the Alternative EWSR1-CREB3L1 Gene Fusion. Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. 2014, 17, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laliberte, C.; Leong, I.T.; Holmes, H.; Monteiro, E.A.; O’Sullivan, B.; Dickson, B.C. Sclerosing Epithelioid Fibrosarcoma of the Jaw: Late Recurrence from a Low Grade Fibromyxoid Sarcoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2017, 12, 619–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesrouani, C.; Zemoura, L.; Trassard, M.; Lae, M. A hybrid lesion: Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma (LGFMS) and sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma (SEF). Ann. Pathol. 2016, 36, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, S.P.; Bowman, C.J.; Wang, Z.J.; Sheahon, K.M.; Nakakura, E.K.; Cho, S.-J.; Umetsu, S.E.; Behr, S.C. Hybrid Low-Grade Fibromyxoid Sarcoma and Sclerosing Epithelioid Fibrosarcoma of the Pancreas. J. Gastrointest. Cancer 2020, 51, 1025–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Thangaiah, J.J.; Shetty, S.; Policarpio-Nicolas, M.L.C. Bone and soft tissue sarcomas in cerebrospinal fluid and effusion: A 20-year review at our institution. Cancer Cytopathol. 2021, 129, 776–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro-Cervello, C.; Benavent Casanova, O.; Nieto, G.; Mares Diago, F.J.; Navarro, S. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma, an essential differential diagnosis in myxoid tumors with benign appearance. Rev. Esp. Patol. 2018, 51, 178–182. [Google Scholar]

- Seto, T.; Song, M.-N.; Trieu, M.; Yu, J.; Sidhu, M.; Liu, C.-M.; Sam, D.; Pan, M. Real-World Experiences with Pazopanib in Patients with Advanced Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma in Northern California. Med. Sci. 2019, 7, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murshed, K.A.; Ammar, A. Hybrid sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma/low grade fibromyxoid sarcoma arising in the small intestine with distinct HEY1-NCOA2 gene fusion. Pathology 2020, 52, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, S.; VandenBussche, C.J.; Ali, S.Z.; Siddiqui, M.T.; Wakely, P.E. Cytomorphologic findings of low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma. J. Am. Soc. Cytopathol. 2020, 9, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colovic, R.; Grubor, N.; Micev, M.; Jovanovic, M.; Radak, V. Fibromyxoid sarcoma of the pancreas. Srp. Arh. Celok. Lek. 2008, 136, 158–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, H.L. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma: A clinicopathologic study of 33 cases with long-term follow-up. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2011, 35, 1450–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbajian, E.; Puls, F.; Magnusson, L.; Thway, K.; Fisher, C.; Sumathi, V.P.; Tayebwa, J.; Nord, K.H.; Kindblom, L.-G.; Mertens, F. Recurrent EWSR1-CREB3L1 Gene Fusions in Sclerosing Epithelioid Fibrosarcoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2014, 38, 801–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, M.A.; Giles, H.W.; Daley, W.P. Massive low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma presenting as acute respiratory distress in a 12-year-old girl. Pediatr. Radiol. 2009, 39, 396–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alter, R.Y.; Wamsley, C.C.; Mullen, J.T.; Haile, W.Z.; Goldsmith, J.D.; Kasper, E.M. Peripheral nerve fibromyxoid sarcoma. J. Neurosurg. 2014, 121, 576–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chetverikova, E.; Kasenõmm, P. Low-Grade Fibromyxoid Sarcoma of the Lateral Skull Base: Presentation of Two Cases. Case Rep. Otolaryngol. 2019, 2019, 7917040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deewani, M.H.; Awan, M.S.; Din, N.U. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma of the parapharyngeal space: An unusual location. BMJ Case Rep. 2021, 14, e237083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notarnicola, A.; Moretti, L.; Cocca, M.P.; Martucci, A.; Orsini, U.; Moretti, B. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma of the medial vastus: A case report. Musculoskelet. Surg. 2010, 94, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, M.; Koide, K.; Arita, M.; Kawaguchi, K.; Mikuriya, Y.; Iwata, J.; Iwamoto, T. A Low-Grade Fibromyxoid Sarcoma of the Internal Abdominal Oblique Muscle. Case Rep. Surg. 2016, 2016, 8524030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, L.-K.; Tseng, A.H.; Huang, S.-H.; Lee, H.H.-C. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma of the external anal sphincter: A case report. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2017, 15, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugalic, V.; Ignjatovic, I.I.; Kovac, J.D.; Ilic, N.; Sopta, J.; Ostojic, S.R.; Vasin, D.; Bogdanovic, M.D.; Dumic, I.; Milovanovic, T. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma of the liver: A case report. World J. Clin. Cases. 2021, 9, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, K.; Johnstone, K.; Lambie, D.; Frankel, A. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma with high-grade features, a rare finding. ANZ J. Surg. 2021, 92, 1519–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaoutoglou, C.; Lykissas, M.G.; Gelalis, I.D.; Batistatou, A.; Goussia, A.; Doukas, M.; Xenakis, T.A. Low grade fibromyxoid sarcoma: A case report and review of the literature. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2010, 5, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, J.; Shukla, S.; Jah, M.; Singh, A.K.; Goel, M.; Mourya, A.; Sachdeva, N. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma around the knee involving the proximal end of the tibia and patella: A rare case report. Oncol. Lett. 2014, 7, 1308–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Indap, S.; Dasgupta, M.; Chakrabarti, N.; Agarwal, A. Low grade fibromyxoid sarcoma (Evans tumour) of the arm. Indian J. Plast. Surg. 2014, 47, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alatise, O.; Oke, O.; Olaofe, O.; Omoniyi-Esan, G.; Adesunkanmi, A. A huge low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma of small bowel mesentery simulating hyper immune splenomegaly syndrome: A case report and review of literature. Afr. Health Sci. 2013, 13, 736–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chitayat, S.; Barros, R.; Ribeiro, J.G.; Silva, H.A.M.; Sa, F.R.; Reis, B.S.B.; Fosse, A.M., Jr. Case Report: An extremely rare occurrence of recurrent inguinal low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma involving the scrotum. F1000Research 2020, 9, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobin, S.M.; Malone, V.S.; Lopez, L.; Donner, L.R. Unusual Histologic Variant of a Low-Grade Fibromyxoid Sarcoma in a 3-Year-Old Boy with Complex Chromosomal Translocations Involving 7q34, 10q11.2, and 16p11.2 and Rearrangement of the FUS Gene. Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. 2013, 16, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedrak, M.P.; Parker, D.C.; Gardner, J.M. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma with nuclear pleomorphism arising in the subcutis of a child. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2013, 41, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billings, S.D.; Giblen, G.; Fanburg-Smith, J.C. Superficial low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma (Evans tumor): A clinicopathologic analysis of 19 cases with a unique observation in the pediatric population. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2005, 29, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, J.A.; Cates, J.M. Differential Diagnostic Considerations of Desmoid-type Fibromatosis. Adv. Anat. Pathol. 2015, 22, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, K.; Thota, R.; Chaudhary, H.L.; Sharma, M.C.; Thakar, A.; Singh, G. Low-Grade Fibromyxoid Sarcoma of the External Auditory Canal: A Rare Pathology and Unusual Location. Head Neck Pathol. 2019, 14, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagopoulos, I.; Storlazzi, C.T.; Fletcher, C.D.; Fletcher, J.A.; Nascimento, A.; Domanski, H.A.; Wejde, J.; Brosjö, O.; Rydholm, A.; Isaksson, M.; et al. The chimeric FUS/CREB3l2 gene is specific for low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma. Genes Chromosom. Cancer 2004, 40, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, L.A.; Möller, E.; Cin, P.D.; Fletcher, C.D.M.; Mertens, F.; Hornick, J.L. MUC4 Is a Highly Sensitive and Specific Marker for Low-grade Fibromyxoid Sarcoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2011, 35, 733–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuyama, A.; Hisaoka, M.; Shimajiri, S.; Hayashi, T.; Imamura, T.; Ishida, T.; Fukunaga, M.; Fukuhara, T.; Minato, H.; Nakajima, T.; et al. Molecular Detection of FUS-CREB3L2 Fusion Transcripts in Low-grade Fibromyxoid Sarcoma Using Formalin-fixed, Paraffin-embedded Tissue Specimens. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2006, 30, 1077–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, P.P.; Lui, P.C.; Lau, G.T.; Yau, D.T.; Cheung, E.T.; Chan, J.K. EWSR1-CREB3L1 gene fusion: A novel alternative molecular aberration of low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2013, 37, 734–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallejo-Benítez, A.; Rodríguez-Zarco, E.; Carrasco, S.P.; Pereira-Gallardo, S.; Molina, J.B.; García-Escudero, A.; Frías, A.R.; Marcilla, D.; González-Cámpora, R. Expression of dog1 in low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma: A study of 19 cases and review of the literature. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 2017, 30, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scolyer, R.A.; Mccarthy, S.W.; Wills, E.J.; Palmer, A.A. Hyalinising spindle cell tumour with giant rosettes: Report of a case with unusual features including original histological and ultrastructural observations. Pathology 2001, 33, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejarano, P.A.; Padhya, T.A.; Smith, R.; Blough, R.; Devitt, J.J.; Gluckman, J.L. Hyalinizing spindle cell tumor with giant rosettes—A soft tissue tumor with mesenchymal and neuroendocrine features. An immunohistochemical, ultrastructural, and cytogenetic analysis. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2000, 124, 1179–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Petrovic, V.; Torode, I.P.; Chow, C.W. Low grade fibromyxoid sarcoma: Problems in the diagnosis and management of a malignant tumour with bland histological appearance. Pathology 2009, 41, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.-H.; Kim, C.-H.; Kim, J.-H.; Park, J.-E.; Yim, S.-Y. Rare Concurrence of Congenital Muscular Torticollis and a Malignant Tumor in the Same Sternocleidomastoid Muscle. Ann. Rehabil. Med. 2018, 42, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puls, F.; Agaimy, A.; Flucke, U.; Mentzel, T.; Sumathi, V.P.; Ploegmakers, M.; Stoehr, R.; Kindblom, L.-G.; Hansson, M.; Sydow, S.; et al. Recurrent Fusions Between YAP1 and KMT2A in Morphologically Distinct Neoplasms Within the Spectrum of Low-grade Fibromyxoid Sarcoma and Sclerosing Epithelioid Fibrosarcoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2020, 44, 594–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, A.; Bridge, J.A.; Liebner, D.; Chung, C.; Iwenofu, O.H. A YAP1::TFE3 cutaneous low-grade fibromyxoid neoplasm: A novel entity! Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2021, 61, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Cohen, S.; Jour, G. Primary small intestine mesenteric low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma with foci of atypical epithelioid whorls and diffuse DOG1 expression: A case report. Diagn. Pathol. 2020, 15, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritch Lilla, S.A.; Yi, J.S.; Hall, B.A.; Moertel, C.L. A novel APC gene mutation associated with a severe phenotype in a patient with Turcot syndrome. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2014, 36, e177–e179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalthoff, S.; Bredt, M.; Gellrich, N.-C.; Jehn, P. A Rare Pathology: Low-Grade Fibromyxoid Sarcoma of the Maxilla. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2016, 74, 219.e1–219.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Broto, J.; Hindi, N.; Lopez-Pousa, A.; Peinado-Serrano, J.; Alvarez, R.; Alvarez-Gonzalez, A.; Italiano, A.; Sargos, P.; Cruz-Jurado, J.; Isern-Verdum, J.; et al. Assessment of Safety and Efficacy of Combined Trabectedin and Low-Dose Radiotherapy for Patients With Metastatic Soft-Tissue Sarcomas: A Non-randomized Phase 1/2 Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020, 6, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Median (IQR) in Years | Total Number Described | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 35 (21–49) | 773 |

| Symptom duration | 1.0 (0.5–4.0) | 181 |

| Follow-up | 3.0 (1.0–6.1) | 545 |

| Time to local recurrence | 2.8 (0.8–6.0) | 143 |

| Time to lung metastasis | 4.0 (0.0–11.3) | 62 |

| Time to metastasis elsewhere | 2.3 (0.0–9.3) | 54 |

| n (%) | ||

| Female (yes) | 389 (50) | 773 |

| Slow growth | 69 (27) | 257 |

| Rapid growth | 24 (9) | 257 |

| Painless | 75 (29) | 257 |

| Painful | 48 (19) | 257 |

| Deep-seated | 475 (80) | 598 |

| MUC4 positive | 243 (57) | 428 |

| Vimentin positive | 198 (46) | 428 |

| Total FUS gene alteration | 263 (83) | 318 |

| FUS/CREB3 positive | 148 (47) | 318 |

| Pathological proven | 472 (61) | 773 |

| Whoops diagnosis | 101 (32) | 314 |

| Surgery | 760 (98) | 773 |

| R0 resection | 279 (66) | 423 |

| R1 resection | 112 (27) | 423 |

| R2 resection | 19 (5) | 423 |

| (Neo)adjuvant chemotherapy | 49 (6) | 773 |

| (Neo)adjuvant radiotherapy | 79 (10) | 773 |

| Complications | 25 (3) | 773 |

| Survival | 501 (92) | 545 |

| Local recurrence | 143 (19) | 545 |

| Lung metastasis | 62 (11) | 545 |

| Metastasis elsewhere | 54 (10) | 545 |

| R0 n (%) | R1 n (%) | R0 vs. R1 p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Survival | 226 (96) | 69 (89) | 0.02 |

| Local recurrence | 24 (9) | 27 (24) | <0.001 |

| Lung metastasis | 11 (4) | 7 (6) | 0.42 |

| Distant metastasis | 15 (5) | 7 (6) | 0.81 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Krebbekx, G.G.J.; Kleine, E.A.; Savci-Heijink, C.D.; Meijer, D.T.; Donner; Hemke, R.; Verspoor, F.G.M. Low-Grade Fibromyxoid Sarcoma and Related Subtypes: A Systematic Review and Pooled Analysis of 773 Cases. Cancers 2026, 18, 364. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18030364

Krebbekx GGJ, Kleine EA, Savci-Heijink CD, Meijer DT, Donner, Hemke R, Verspoor FGM. Low-Grade Fibromyxoid Sarcoma and Related Subtypes: A Systematic Review and Pooled Analysis of 773 Cases. Cancers. 2026; 18(3):364. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18030364

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrebbekx, Gitte G. J., Elisabeth A. Kleine, C. Dilara Savci-Heijink, Diederik T. Meijer, Donner, Robert Hemke, and Floortje G. M. Verspoor. 2026. "Low-Grade Fibromyxoid Sarcoma and Related Subtypes: A Systematic Review and Pooled Analysis of 773 Cases" Cancers 18, no. 3: 364. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18030364

APA StyleKrebbekx, G. G. J., Kleine, E. A., Savci-Heijink, C. D., Meijer, D. T., Donner, Hemke, R., & Verspoor, F. G. M. (2026). Low-Grade Fibromyxoid Sarcoma and Related Subtypes: A Systematic Review and Pooled Analysis of 773 Cases. Cancers, 18(3), 364. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18030364