First-Line Chemotherapy Regimens for Advanced and Metastatic Leiomyosarcoma: Doxorubicin vs. Gemcitabine—A Systematic Review

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Collection

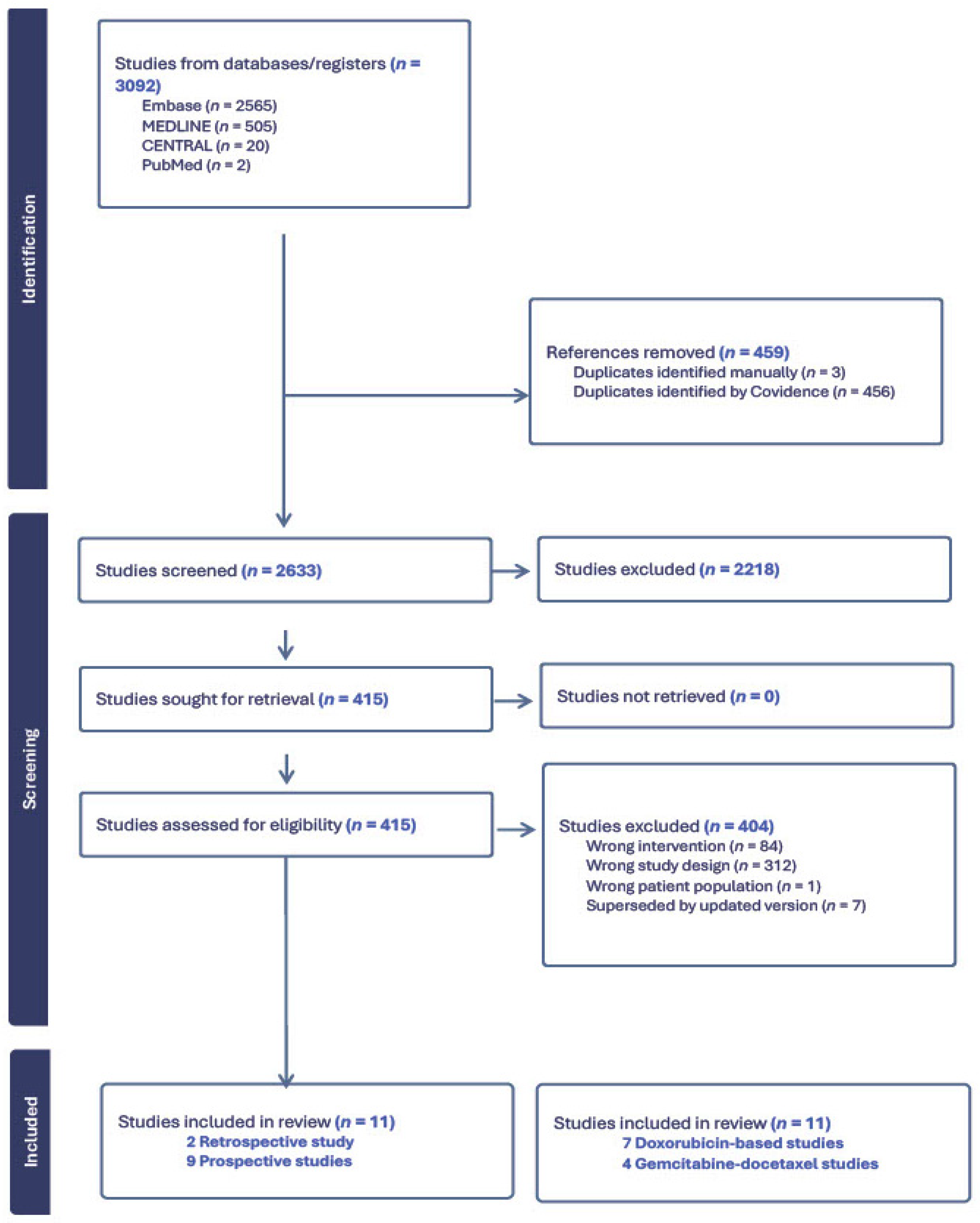

2.4. PRISMA

3. Results

- (1)

- Doxorubicin-based regimens, including combinations with ifosfamide, dacarbazine, trabectedin, and immunotherapy.

- (2)

- Gemcitabine–docetaxel-based regimens, including combinations with bevacizumab.

3.1. Doxorubicin-Based Studies

3.1.1. Population and Response Characteristics

3.1.2. Adverse Effects

3.2. Gemcitabine-Based Studies

3.2.1. Population and Response Characteristics

3.2.2. Adverse Effects

4. Discussion

4.1. Cytotoxic Efficacy

4.2. Treatment Tolerability

4.3. Patient Selection and Disease Heterogeneity

4.4. Emerging Therapies and Future Directions

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LMS | Leiomyosarcoma |

| STS | Soft-tissue sarcoma |

| GD | Gemcitabine–docetaxel |

| STLMS | Non-uterine soft tissue |

| uLMS | Uterine soft tissue |

References

- Board, W. Soft tisse and bone tumors. In WHO Classification of Tumors, 5th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mastrangelo, G.; Coindre, J.-M.; Ducimetière, F.; Dei Tos, A.P.; Fadda, E.; Blay, J.-Y.; Buja, A.; Fedeli, U.; Cegolon, L.; Frasson, A.; et al. Incidence of soft tissue sarcoma and beyond. Cancer 2012, 118, 5339–5348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadeo, B.; Penel, N.; Coindre, J.-M.; Ray-Coquard, I.; Ligier, K.; Delafosse, P.; Bouvier, A.-M.; Plouvier, S.; Gallet, J.; Lacourt, A.; et al. Incidence and time trends of sarcoma (2000–2013): Results from the French network of cancer registries (FRANCIM). BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worhunsky, D.J.; Gupta, M.; Gholami, S.; Tran, T.B.; Ganjoo, K.N.; van de Rijn, M.; Visser, B.C.; Norton, J.A.; Poultsides, G.A. Leiomyosarcoma: One disease or distinct biologic entities based on site of origin? J. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 111, 808–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gootee, J.; Sioda, N.; Aurit, S.; Curtin, C.; Silberstein, P. Important prognostic factors in leiomyosarcoma survival: A National Cancer Database (NCDB) analysis. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2020, 22, 860–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, S.; Serrano, C.; Hensley, M.L.; Ray-Coquard, I. Soft Tissue and Uterine Leiomyosarcoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gage, M.M.; Nagarajan, N.; Ruck, J.M.; Canner, J.K.; Khan, S.; Giuliano, K.; Gani, F.; Wolfgang, C.; Johnston, F.M.; Ahuja, N. Sarcomas in the United States: Recent trends and a call for improved staging. Oncotarget 2019, 10, 2462–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Shi, N.; Naing, A.; Janku, F.; Subbiah, V.; Araujo, D.M.; Patel, S.R.; Ludwig, J.A.; Ramondetta, L.M.; Levenback, C.F.; et al. Survival of patients with metastatic leiomyosarcoma: The MD Anderson Clinical Center for targeted therapy experience. Cancer Med. 2016, 5, 3437–3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacuna, K.; Bose, S.; Ingham, M.; Schwartz, G. Therapeutic advances in leiomyosarcoma. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1149106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Mehren, M.; Kane, J.M.; Agulnik, M.; Bui, M.M.; Carr-Ascher, J.; Choy, E.; Connelly, M.; Dry, S.; Ganjoo, K.N.; Gonzalez, R.J.; et al. Soft Tissue Sarcoma, Version 2.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Canc Netw. 2022, 20, 815–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddon, B.; Strauss, S.J.; Whelan, J.; Leahy, M.; Woll, P.J.; Cowie, F.; Rothermundt, C.; Wood, Z.; Benson, C.; Ali, N.; et al. Gemcitabine and docetaxel versus doxorubicin as first-line treatment in previously untreated advanced unresectable or metastatic soft-tissue sarcomas (GeDDiS): A randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 1397–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taube, J.M.; Klein, A.; Brahmer, J.R.; Xu, H.; Pan, X.; Kim, J.H.; Chen, L.; Pardoll, D.M.; Topalian, S.L.; Anders, R.A. Association of PD-1, PD-1 ligands, and other features of the tumor immune microenvironment with response to anti-PD-1 therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 5064–5074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, L.; Lemery, S.J.; Keegan, P.; Pazdur, R. FDA Approval Summary: Pembrolizumab for the Treatment of Microsatellite Instability-High Solid Tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 3753–3758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Angelo, S.P.; Mahoney, M.R.; Van Tine, B.A.; Atkins, J.; Milhem, M.M.; Jahagirdar, B.N.; Antonescu, C.R.; Horvath, E.; Tap, W.D.; Schwartz, G.K.; et al. Nivolumab with or without ipilimumab treatment for metastatic sarcoma (Alliance A091401): Two open-label, non-comparative, randomised, phase 2 trials. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Therasse, P.; Arbuck, S.G.; Eisenhauer, E.A.; Wanders, J.; Kaplan, R.S.; Rubinstein, L.; Verweij, J.; Van Glabbeke, M.; van Oosterom, A.T.; Christian, M.C.; et al. New Guidelines to Evaluate the Response to Treatment in Solid Tumors. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2000, 92, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhauer, E.A.; Therasse, P.; Bogaerts, J.; Schwartz, L.H.; Sargent, D.; Ford, R.; Dancey, J.; Arbuck, S.; Gwyther, S.; Mooney, M.; et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur. J. Cancer 2009, 45, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maki, R.G.; Wathen, J.K.; Patel, S.R.; Priebat, D.A.; Okuno, S.H.; Samuels, B.; Fanucchi, M.; Harmon, D.C.; Schuetze, S.M.; Reinke, D.; et al. Randomized phase II study of gemcitabine and docetaxel compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with metastatic soft tissue sarcomas: Results of sarcoma alliance for research through collaboration study 002 [corrected]. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 2755–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Broto, J.; Diaz-Beveridge, R.; Moura, D.; Ramos, R.; Martinez-Trufero, J.; Carrasco, I.; Sebio, A.; González-Billalabeitia, E.; Gutierrez, A.; Fernandez-Jara, J.; et al. Phase Ib Study for the Combination of Doxorubicin, Dacarbazine, and Nivolumab as the Upfront Treatment in Patients with Advanced Leiomyosarcoma: A Study by the Spanish Sarcoma Group (GEIS). J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, G.; Blessing, J.A.; Malfetano, J.H. Ifosfamide and doxorubicin in the treatment of advanced leiomyosarcomas of the uterus: A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol. Oncol. 1996, 62, 226–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmonson, J.H.; Blessing, J.A.; Cosin, J.A.; Miller, D.S.; Cohn, D.E.; Rotmensch, J. Phase II study of mitomycin, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in the treatment of advanced uterine leiomyosarcoma: A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2002, 85, 507–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadoux, J.; Rey, A.; Duvillard, P.; Lhommé, C.; Balleyguier, C.; Haie-Meder, C.; Morice, P.; Tazi, Y.; Leary, A.; Larue, C.; et al. Multimodal treatment with doxorubicin, cisplatin, and ifosfamide for the treatment of advanced or metastatic uterine leiomyosarcoma: A unicentric experience. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2015, 25, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pautier, P.; Floquet, A.; Chevreau, C.; Penel, N.; Guillemet, C.; Delcambre, C.; Cupissol, D.; Selle, F.; Isambert, N.; Piperno-Neumann, S.; et al. Trabectedin in combination with doxorubicin for first-line treatment of advanced uterine or soft-tissue leiomyosarcoma (LMS-02): A non-randomised, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ambrosio, L.; Touati, N.; Blay, J.-Y.; Grignani, G.; Flippot, R.; Czarnecka, A.M.; Piperno-Neumann, S.; Martin-Broto, J.; Sanfilippo, R.; Katz, D.; et al. Doxorubicin plus dacarbazine, doxorubicin plus ifosfamide, or doxorubicin alone as a first-line treatment for advanced leiomyosarcoma: A propensity score matching analysis from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group. Cancer 2020, 126, 2637–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pautier, P.; Italiano, A.; Piperno-Neumann, S.; Chevreau, C.; Penel, N.; Firmin, N.; Boudou-Rouquette, P.; Bertucci, F.; Lebrun-Ly, V.; Ray-Coquard, I.; et al. Doxorubicin–Trabectedin with Trabectedin Maintenance in Leiomyosarcoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensley, M.L.; Blessing, J.A.; Mannel, R.; Rose, P.G. Fixed-dose rate gemcitabine plus docetaxel as first-line therapy for metastatic uterine leiomyosarcoma: A Gynecologic Oncology Group phase II trial. Gynecol. Oncol. 2008, 109, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensley, M.L.; Miller, A.; O’Malley, D.M.; Mannel, R.S.; Behbakht, K.; Bakkum-Gamez, J.N.; Michael, H. Randomized phase III trial of gemcitabine plus docetaxel plus bevacizumab or placebo as first-line treatment for metastatic uterine leiomyosarcoma: An NRG Oncology/Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 1180–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddon, B.; Scurr, M.; Jones, R.L.; Wood, Z.; Propert-Lewis, C.; Fisher, C.; Flanagan, A.; Sunkersing, J.; A’Hern, R.; Whelan, J.; et al. A phase II trial to assess the activity of gemcitabine and docetaxel as first line chemotherapy treatment in patients with unresectable leiomyosarcoma. Clin. Sarcoma Res. 2015, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pautier, P.; Italiano, A.; Piperno-Neumann, S.; Chevreau, C.; Penel, N.; Firmin, N.; Boudou-Rouquette, P.; Bertucci, F.; Balleyguier, C.; Lebrun-Ly, V.; et al. Doxorubicin alone versus doxorubicin with trabectedin followed by trabectedin alone as first-line therapy for metastatic or unresectable leiomyosarcoma (LMS-04): A randomised, multicentre, open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 1044–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Cesne, A.; Blay, J.Y.; Domont, J.; Tresch-Bruneel, E.; Chevreau, C.; Bertucci, F.; Delcambre, C.; Saada-Bouzid, E.; Piperno-Neumann, S.; Bay, J.O.; et al. Interruption versus continuation of trabectedin in patients with soft-tissue sarcoma (T-DIS): A randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, G.P.; Blessing, J.A.; Rosenshein, N.; Photopulos, G.; DiSaia, P.J. Phase II trial of ifosfamide and mesna in mixed mesodermal tumors of the uterus (a Gynecologic Oncology Group study). Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1989, 161, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, G.P.; Blessing, J.A.; Barrett, R.J.; McGehee, R. Phase II trial of ifosfamide and mesna in leiomyosarcoma of the uterus: A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1992, 166, 556–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, M.B.; Jagosky, M.H.; Robinson, M.M.; Ahrens, W.A.; Benbow, J.H.; Farhangfar, C.J.; Foureau, D.M.; Maxwell, D.M.; Baldrige, E.A.; Begic, X. Phase II study of pembrolizumab in combination with doxorubicin in metastatic and unresectable soft-tissue sarcoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 6424–6431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, E.; Qin, L.-X.; Thornton, K.A.; Movva, S.; Nacev, B.A.; Dickson, M.A.; Gounder, M.M.; Keohan, M.L.; Avutu, V.; Chi, P. A phase I/II trial of the PD-1 inhibitor retifanlimab (R) in combination with gemcitabine and docetaxel (GD) as first-line therapy in patients (Pts) with advanced soft-tissue sarcoma (STS). J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 11516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smrke, A.; Ostler, A.; Napolitano, A.; Vergnano, M.; Asare, B.; Fotiadis, N.; Thway, K.; Zaidi, S.; Miah, A.; Van Der Graaf, W. 1526MO GEMMK: A phase I study of gemcitabine (gem) and pembrolizumab (pem) in patients (pts) with leiomyosarcoma (LMS) and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma UPS. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, S1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C.W.; Merimsky, O.; Agulnik, M.; Blay, J.Y.; Schuetze, S.M.; Van Tine, B.A.; Jones, R.L.; Elias, A.D.; Choy, E.; Alcindor, T.; et al. PICASSO III: A Phase III, Placebo-Controlled Study of Doxorubicin with or Without Palifosfamide in Patients with Metastatic Soft Tissue Sarcoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 3898–3905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tap, W.D.; Wagner, A.J.; Schöffski, P.; Martin-Broto, J.; Krarup-Hansen, A.; Ganjoo, K.N.; Yen, C.C.; Abdul Razak, A.R.; Spira, A.; Kawai, A.; et al. Effect of Doxorubicin Plus Olaratumab vs Doxorubicin Plus Placebo on Survival in Patients with Advanced Soft Tissue Sarcomas: The ANNOUNCE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2020, 323, 1266–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tap, W.D.; Papai, Z.; Van Tine, B.A.; Attia, S.; Ganjoo, K.N.; Jones, R.L.; Schuetze, S.; Reed, D.; Chawla, S.P.; Riedel, R.F.; et al. Doxorubicin plus evofosfamide versus doxorubicin alone in locally advanced, unresectable or metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma (TH CR-406/SARC021): An international, multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 1089–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movva, S.; Seier, K.; Bradic, M.; Charalambous, K.; Rosenbaum, E.; Kelly, C.M.; Cohen, S.M.; Hensley, M.L.; Avutu, V.; Banks, L.B.; et al. Phase II study of rucaparib and nivolumab in patients with leiomyosarcoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, e012020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Year | Type of Study | Type of Sarcoma | Regimen | Number of Patients (n) | ORR | Median PFS Duration | Median OS Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sutton et al. [20] | 1996 | Prospective phase 2 trial | Advanced uLMS | Doxorubicin and ifosfamide | 35 | 30.3%; n = 10/35 PR—9 CR—1 SD—17 | Median duration of response: 4.1 months | 9.6 months |

| Edmonson et al. [21] | 2002 | Prospective phase 2 trial | uLMS | Doxorubicin, mitomycin and cisplatin | 37 (35 evaluable) | 23%; n = 8/35 PR—5 CR—3 SD—14 | Not reported | 6.3 months |

| Hadoux et al. [22] | 2015 | Retrospective monocentric study | Metastatic and locally advanced uLMS | Doxorubicin, cisplatin and ifosfamide | 38 (33 evaluable) | 48%; n = 16/33 PR—12 CR—4 SD—8 | 9.8 months | 27 months |

| Pautier et al. [23] | 2015 | Prospective non-randomized, multicenter phase 2 trial | Advanced uLMS and LMS | Doxorubicin and trabectedin | 108 47—uLMS 61—LMS | 59.6%; n = 28/47 PR—28 SD—13 DC—41 39.3%; n = 24/61 CR—2 PR—22 SD—32 DC—56 | 8.2 months 12.9 months | 20.2 months 34.5 months |

| D’Ambrosio et al. [24] | 2020 | Retrospective multicenter cohort study | LMS | Doxorubicin and dacarbazine, doxorubicin and ifosfamide, or doxorubicin alone | 303 117—doxorubicin and dacarbazine 71—doxorubicin and ifosfamide 115—doxorubicin alone | 30.9% 19.5% 25.6% | 9.2 months 8.2 months 4.8 months p = 0.0023 HR 0.72 | 36.8 months 21.9 months HR 0.65 30.3 months HR 0.66 p = 0.2089 |

| Pautier et al. [25] | 2024 | Prospective randomized, multicenter, open-label phase 3 trial | Locally advanced or metastatic uLMS and LMS | Doxorubicin and trabectedin, followed by trabectedin maintenance vs. doxorubicin alone | 150 67—uLMS 83—LMS 76—doxorubicin alone group 74—doxorubicin and trabectedin group | 13.2%; n = 10/76 36.5%; n = 27/74 | 6.2 months 12.2 months p ≤ 0.0001 HR 0.37 | 23.8 months 33.1 months p = 0.0253 HR 0.65 OS at 2 years doxorubicin alone (49%) doxorubicin/trabectedin (68%) |

| Martin-Broto et al. [19] | 2025 | Prospective, single-arm cohort phase 1b trial | Advanced LMS and uLMS | Doxorubicin, dacarbazine, and nivolumab | 26 11—uLMS 15—LMS | 56.5%; n = 13/23 PR—13/23 SD—9/23 PD—1/23 | 8.7 months | Not reached 1-year OS rate was 82% |

| Maki et al. [18] | 2007 | Prospective randomized phase 2 trial | Metastatic STS | Gemcitabine and docetaxel vs. gemcitabine alone | 122 49—gemcitabine 9—LMS 73—gemcitabine and docetaxel 29—LMS | 27%; n = 13/49 PR—4/49 SD—26/49 PD—18/49 LMS-specific PR—1/9 32%; n = 23/73 CR—2/73 PR—10/73 SD—39/73 PD—18/73 LMS-specific PR—5/29 | 6.2 months 3.0 months P (superiority) = 0.98 | 17.9 months 11.5 months P (superiority) = 0.97 |

| Hensley et al. [26] | 2008 | Prospective phase 2 trial | Metastatic uLMS | Gemcitabine and docetaxel | 42 | 35.8%; n = 15/42 CR—2/42 PR—13/42 SD—11/42 PD—13/42 | 4.4 months | 16.1 months |

| Hensley et al. [27] | 2015 | Prospective randomized phase 3 trial | Metastatic uLMS | Gemcitabine, docetaxel, and bevacizumab vs. gemcitabine, docetaxel, and placebo | 107 54—gemcitabine, docetaxel, and placebo 53—gemcitabine, docetaxel, and bevacizumab | 31.5%; n = 17/54 SD—17/54 35.8%; n = 19/53 SD—17/54 p = 0.69 | 6.2 months 4.2 months p = 0.58 HR 1.12 | 26.9 months 23.3 months p = 0.81 HR 1.07 |

| Seddon et al. [28] | 2015 | Prospective phase 2 trial | Unresectable LMS | Gemcitabine and docetaxel | 44 | 25%; n = 11/44 PR—11/44 SD—16/44 PD—10/44 | 7.1 months | 17.9 months |

| Study and Year | Chemotherapy Regimen | Grade 3 or 4 Events | Grade 5 Events | Grade 3 or 4 Neutropenia | Grade 3 or 4 Febrile Neutropenia | Grade 3 or 4 Liver Toxicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sutton et al., 1996 [20] | Doxorubicin and ifosfamide | Granulocytopenia—48.6% (17/34) | 5.9% (2/34) | None reported | 5.7% (2/34) | None reported |

| Edmonson et al., 2002 [21] | Doxorubicin, mitomycin, and cisplatin | Leukopenia—89% (33/37) Thrombocytopenia—81% (30/37) | 5.4% (2/37) | None reported | None reported | 2.7% (1/37) |

| Hadoux et al., 2015 [22] | Doxorubicin, cisplatin, and ifosfamide | Nausea—11% (4/38) Vomiting—13% (5/38) Asthenia—18% (7/38) Anemia—55% (20/38) Thrombocytopenia—60% (23/38) | 2.6% (1/38) | 74% (28/38) | 37% (14/38) | None reported |

| Pautier et al., 2015 [23] | Doxorubicin and trabectedin | Thrombocytopenia—37% (40/108) Anemia—27% (29/108) Fatigue—19% (21/180) Leucocytes—76% (82/108) | 2.8% (3/108) | 78% (84/108) | 24% (26/108) | Increased ALT—39% (42/108) |

| D’Ambrosio et al., 2020 [24] | Doxorubicin and dacarbazine, doxorubicin and ifosfamide, or doxorubicin alone | None reported | None reported | None reported | None reported | None reported |

| Pautier at al., 2024 [25] | Doxorubicin alone | Anemia—12% (9/75) Leukopenia—5.33% (4/75) | Cardiac failure −1.33% (1/75) | 16% (12/75) | 9.33% (7/75) | Increased ALT—1% (1/75) Increased AST—1% (1/75) |

| Doxorubicin and trabectedin | Anemia—51.35% (38/74) Leukopenia—98.6% (73/74) Thrombocytopenia—60.81% (45/74) | 0 | Cycle 1 to 6—77.02% (57/74) Cycle 6 to progression—41.9% (31/74) | 21.62% (16/74) | Increased ALT—53% (39/74) Increased AST—16% (12/74) Increased ALP—4% (3/74) Increased bilirubin—11% (8/74) | |

| Martin-Broto et al., 2025 [19] | Doxorubicin, dacarbazine, and nivolumab | Anemia—20.8% (5/23) Leukopenia—25% (6/23) | 0 | 33.4% (8/23) | 4.2% (1/23) | None reported |

| Maki et al., 2007 [18] | Gemcitabine alone | Hemoglobin—13% (6/49) Thrombocytopenia—35% (17/49) | 0 | 28% (14/49) | 7% (3/49) | None reported |

| Gemcitabine and docetaxel | Hemoglobin—7% (5/73) Thrombocytopenia—40% (29/73) | 0 | 16% (12/73) | 5% (4/73) | None reported | |

| Hensley et al., 2008 [26] | Gemcitabine and docetaxel | Leukopenia—14% (6/42) Thrombocytopenia—14% (6/42) Anemia—24% (10/42) | 0 | 16.7% (7/42) | None reported | Elevated AST or ALT—2% (7/42) |

| Hensley et al., 2015 [27] | Gemcitabine, docetaxel, and placebo | Anemia—33% (17/51) Thrombocytopenia—28% (15/51) | 0 | 23% (12/51) | None reported | None reported |

| Gemcitabine, docetaxel, and bevacizumab | Anemia—13% (7/52) Thrombocytopenia—36% (19/52). | 0 | 22% (12/52) | None reported | None reported | |

| Seddon et al., 2015 [28] | Gemcitabine and docetaxel | Anemia—24% (10/42) Thrombocytopenia—7% (3/42) Fatigue—31% (13/42) Dyspnea—17% (7/42) Infection—12% (5/42) | 0 | 12% (5/42) | None reported | None reported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Khan, I.; Agarwal, P.; Assaad, N.E.; Ratan, R.; Nassif Haddad, E.F. First-Line Chemotherapy Regimens for Advanced and Metastatic Leiomyosarcoma: Doxorubicin vs. Gemcitabine—A Systematic Review. Cancers 2026, 18, 335. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020335

Khan I, Agarwal P, Assaad NE, Ratan R, Nassif Haddad EF. First-Line Chemotherapy Regimens for Advanced and Metastatic Leiomyosarcoma: Doxorubicin vs. Gemcitabine—A Systematic Review. Cancers. 2026; 18(2):335. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020335

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhan, Ilma, Priyal Agarwal, Nassar El Assaad, Ravin Ratan, and Elise F. Nassif Haddad. 2026. "First-Line Chemotherapy Regimens for Advanced and Metastatic Leiomyosarcoma: Doxorubicin vs. Gemcitabine—A Systematic Review" Cancers 18, no. 2: 335. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020335

APA StyleKhan, I., Agarwal, P., Assaad, N. E., Ratan, R., & Nassif Haddad, E. F. (2026). First-Line Chemotherapy Regimens for Advanced and Metastatic Leiomyosarcoma: Doxorubicin vs. Gemcitabine—A Systematic Review. Cancers, 18(2), 335. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020335