Targeting Monocytes and Their Derivatives in Ovarian Cancer: Opportunities for Innovation in Prognosis and Therapy

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

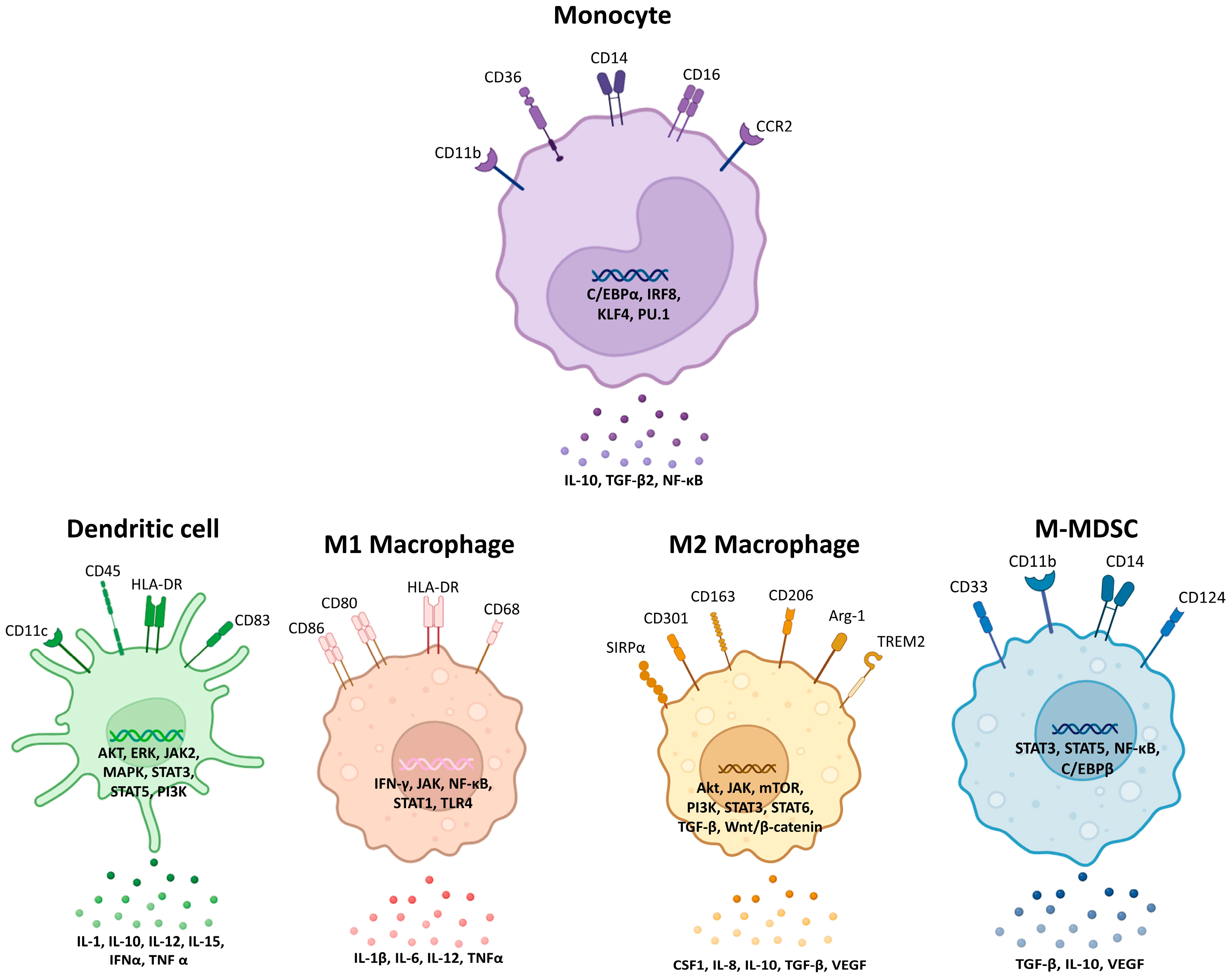

2. Monocytes, Macrophages, Dendritic Cells, and Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells: Origins, Functions, and Evolving Concepts in Ovarian Cancer

2.1. Monocytes

2.2. Macrophages

2.3. Dendritic Cells

2.4. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells

3. Therapeutic Strategies Targeting Monocytes and Their Derivatives in Ovarian Cancer

3.1. Targeting Monocyte Recruitment

3.2. Macrophage Reprogramming

3.3. Targeting Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells (MDSCs)

3.4. Dendritic Cell (DC) Therapies

4. Prognostic Significance of Monocytes in Ovarian Cancer

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AKT | Protein kinase B |

| ALDH+ | Aldehyde dehydrogenase-positive |

| APCs | Antigen-presenting cells |

| ARG1 | Arginase-1 |

| C/EBPα | CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha |

| C5 | Complement component C5 |

| CA-125 | Cancer antigen 125 |

| CAR-M | Chimeric antigen receptor macrophage |

| cDCs | Conventional dendritic cells |

| CMOP | Common monocyte progenitor |

| CSF-1 | Colony stimulating factor 1 |

| CSF-1R | Colony stimulating factor 1 receptor |

| DCs | Dendritic cells |

| EMT | Epithelial-mesenchymal transition |

| EOC | Epithelial ovarian cancer |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| EVs | Extracellular vesicles |

| FIGO | International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics |

| GM-CSF | Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

| HE4 | Human epididymis protein 4 |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| IDO | Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase |

| IFN-α | Interferon-alpha |

| IFN-γ | Interferon-gamma |

| IL | Interleukin |

| iNOS | Inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| IRF | Interferon regulatory factor |

| JAK | Janus kinase |

| KLF4 | Krueppel-like factor 4 |

| LMR | Lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| mDCs | Myeloid dendritic cells |

| MDSCs | Myeloid-derived suppressor cells |

| MHC | Major histocompatibility complex |

| MLR | Monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio |

| MMCs | Myeloid mononuclear cells |

| M-MDSCs | Monocytic MDSCs |

| MMPs | Matrix metalloproteinases |

| NF-κb | Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NK | Natural killer |

| OC | Ovarian Cancer |

| OS | Overall survival |

| PD-1 | Programmed death-1 |

| pDCs | Plasmacytoid dendritic cells |

| PDGF | Platelet-derived growth factor |

| PD-L1 | Programmed death-ligand 1 |

| PFS | Progression-free survival |

| PGE2 | Prostaglandin E2 |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| PMN-/G-MDSCs | Polymorphonuclear or granulocytic MDSCs |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| STAT | Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription |

| TAMs | Tumour-associated macrophages |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor beta |

| TME | Tumour microenvironment |

| TNF-α | Tumour necrosis factor-alpha |

| Tregs | Regulatory T cells |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, G.; Weroha, S.J.; Cliby, W. Ovarian Cancer: A Review. JAMA 2025, 334, 1278–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farghaly, S.A. Advances in Diagnosis and Management of Ovarian Cancer; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, W.H.; DeFazio, A.; Kasherman, L. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in ovarian cancer: Where do we go from here? Cancer Drug Resist. 2023, 6, 358–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giornelli, G.H. Management of relapsed ovarian cancer: A review. Springerplus 2016, 5, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindemann, K.; Gao, B.; Mapagu, C.; Fereday, S.; Emmanuel, C.; Alsop, K.; Traficante, N.; Harnett, P.R.; Bowtell, D.D.L.; deFazio, A. Response rates to second-line platinum-based therapy in ovarian cancer patients challenge the clinical definition of platinum resistance. Gynecol. Oncol. 2018, 150, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilliams, M.; Mildner, A.; Yona, S. Developmental and functional heterogeneity of monocytes. Immunity 2018, 49, 595–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, S.; Plüddemann, A.; Martinez Estrada, F. Macrophage heterogeneity in tissues: Phenotypic diversity and functions. Immunol. Rev. 2014, 262, 36–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzerodt, A.; Moulin, M.; Doktor, T.K.; Delfini, M.; Mossadegh-Keller, N.; Bajenoff, M.; Sieweke, M.H.; Moestrup, S.K.; Auphan-Anezin, N.; Lawrence, T. Tissue-resident macrophages in omentum promote metastatic spread of ovarian cancer. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 217, e20191869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.Q. The mechanism of the anticancer function of M1 macrophages and their use in the clinic. Chin. J. Cancer 2012, 31, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaishi, K.; Komohara, Y.; Tashiro, H.; Ohtake, H.; Nakagawa, T.; Katabuchi, H.; Takeya, M. Involvement of M2-polarized macrophages in the ascites from advanced epithelial ovarian carcinoma in tumor progression via Stat3 activation. Cancer Sci. 2010, 101, 2128–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, A.A.; Hufnagel, D.H.; Harris, W.; Bullock, K.; Glass, E.B.; Liu, E.; Barham, W.; Crispens, M.A.; Khabele, D.; Giorgio, T.D.; et al. Increased canonical NF-kappaB signaling specifically in macrophages is sufficient to limit tumor progression in syngeneic murine models of ovarian cancer. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teleanu, R.I.; Chircov, C.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Teleanu, D.M. Tumor angiogenesis and anti-angiogenic strategies for cancer treatment. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 9, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinartz, S.; Schumann, T.; Finkernagel, F.; Wortmann, A.; Jansen, J.M.; Meissner, W.; Krause, M.; Schworer, A.M.; Wagner, U.; Muller-Brusselbach, S.; et al. Mixed-polarization phenotype of ascites-associated macrophages in human ovarian carcinoma: Correlation of CD163 expression, cytokine levels and early relapse. Int. J. Cancer 2014, 134, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, R.J.A.; Hoogstad-van Evert, J.S.; Hagemans, I.M.; Brummelman, J.; van Ens, D.; de Jonge, P.; Hooijmaijers, L.; Mahajan, S.; van der Waart, A.B.; Hermans, C.; et al. Increased peritoneal TGF-beta1 is associated with ascites-induced NK-cell dysfunction and reduced survival in high-grade epithelial ovarian cancer. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1448041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Wu, Y.; Li, Q.; Hong, W.; Yang, Y.; Hu, X.; Yang, Y.; Lu, T.; Zhao, X.; Wei, X. Colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor inhibition combined with paclitaxel exerts effective antitumor effects in the treatment of ovarian cancer. Genes Dis. 2024, 11, 100989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Parayath, N.N.; Ene, C.I.; Stephan, S.B.; Koehne, A.L.; Coon, M.E.; Holland, E.C.; Stephan, M.T. Genetic programming of macrophages to perform anti-tumor functions using targeted mRNA nanocarriers. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-J.; Hodeib, M.; Chang, J.; Bristow, R.E. Survival impact of complete cytoreduction to no gross residual disease for advanced-stage ovarian cancer: A meta-analysis. Gynecol. Oncol. 2013, 130, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraji, M.; Sudo, T.; Iwasaki, S.-i.; Ueno, S.; Wakahashi, S.; Yamaguchi, S.; Fujiwara, K.; Nishimura, R. Histopathology predicts clinical outcome in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and debulking surgery. Gynecol. Oncol. 2013, 131, 531–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.-p.; Liu, Y.-h.; Liu, Z.-y.; Wang, L.-j.; Jing, C.-x.; Zhu, S.; Zeng, F.-f. Pretreatment lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio as a predictor of survival among patients with ovarian cancer: A meta-analysis. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, 11, 1907–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cucurull, M.; Felip, E.; Garcia, J.J.; Erasun, C.; Angelats, L.; Teruel, I.; Martinez-Román, S.; Hernández, J.; Esteve, A.; España, S.; et al. Prognostic value of monocyte to lymphocyte ratio (MLR) in epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC). J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, e17066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-Nunes, D.L.; Mendes-Frias, A.; Silvestre, R.; Dinis-Oliveira, R.J.; Ricardo, S. Immune tumor microenvironment in ovarian cancer ascites. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, J.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, C.; Cai, L.; Li, D.; Cao, J. Progress in applicability of scoring systems based on nutritional and inflammatory parameters for ovarian cancer. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 809091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Fang, Y.; Mo, Z.; Lin, Y.; Ji, C.; Jian, Z. Prognostic value of lymphocyte to monocyte ratio in pancreatic cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis including 3338 patients. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 18, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, P.; Low, E.; Harper, E.; Stack, M.S. Metalloproteinases in ovarian cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Bairi, K.; Al Jarroudi, O.; Afqir, S. Inexpensive systemic inflammatory biomarkers in ovarian cancer: An umbrella systematic review of 17 prognostic meta-analyses. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 694821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinman, R.M. Decisions about dendritic cells: Past, present, and future. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2012, 30, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynn, T.A.; Vannella, K.M. Macrophages in tissue repair, regeneration, and fibrosis. Immunity 2016, 44, 450–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amit, I.; Winter, D.R.; Jung, S. The role of the local environment and epigenetics in shaping macrophage identity and their effect on tissue homeostasis. Nat. Immunol. 2016, 17, 18–25, Erratum in Nat. Immunol. 2017, 18, 246. https://doi.org/10.1038/ni0217-246b. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G.D.; Hamers, A.A.; Nakao, C.; Marcovecchio, P.; Taylor, A.M.; McSkimming, C.; Nguyen, A.T.; McNamara, C.A.; Hedrick, C.C. Human blood monocyte subsets: A new gating strategy defined using cell surface markers identified by mass cytometry. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2017, 37, 1548–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.A.; Zhang, Y.; Fullerton, J.N.; Boelen, L.; Rongvaux, A.; Maini, A.A.; Bigley, V.; Flavell, R.A.; Gilroy, D.W.; Asquith, B.; et al. The fate and lifespan of human monocyte subsets in steady state and systemic inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 2017, 214, 1913–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawamura, S.; Onai, N.; Miya, F.; Sato, T.; Tsunoda, T.; Kurabayashi, K.; Yotsumoto, S.; Kuroda, S.; Takenaka, K.; Akashi, K.; et al. Identification of a human clonogenic progenitor with strict monocyte differentiation potential: A counterpart of mouse cMoPs. Immunity 2017, 46, 835–848.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champhekar, A.; Damle, S.S.; Freedman, G.; Carotta, S.; Nutt, S.L.; Rothenberg, E.V. Regulation of early T-lineage gene expression and developmental progression by the progenitor cell transcription factor PU.1. Genes Dev. 2015, 29, 832–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laiosa, C.V.; Stadtfeld, M.; Xie, H.; de Andres-Aguayo, L.; Graf, T. Reprogramming of committed T cell progenitors to macrophages and dendritic cells by C/EBPα and PU.1 transcription factors. Immunity 2006, 25, 731–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, T.; Thotakura, P.; Tanaka, T.S.; Ko, M.S.; Ozato, K. Identification of target genes and a unique cis element regulated by IRF-8 in developing macrophages. Blood 2005, 106, 1938–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurotaki, D.; Osato, N.; Nishiyama, A.; Yamamoto, M.; Ban, T.; Sato, H.; Nakabayashi, J.; Umehara, M.; Miyake, N.; Matsumoto, N.; et al. Essential role of the IRF8-KLF4 transcription factor cascade in murine monocyte differentiation. Blood 2013, 121, 1839–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegler-Heitbrock, L.; Ancuta, P.; Crowe, S.; Dalod, M.; Grau, V.; Hart, D.N.; Leenen, P.J.; Liu, Y.-J.; MacPherson, G.; Randolph, G.J.; et al. Nomenclature of monocytes and dendritic cells in blood. Blood 2010, 116, e74–e80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passlick, B.; Flieger, D.; Ziegler-Heitbrock, H. Identification and characterization of a novel monocyte subpopulation in human peripheral blood. Blood 1989, 74, 2527–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odunsi, K. Immunotherapy in ovarian cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, viii1–viii7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.; Klink, M. The Role of Tumor-Associated Macrophages in the Progression and Chemoresistance of Ovarian Cancer. Cells 2020, 9, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Ma, C.; Wu, Q.; Yu, M. Ovarian cancer derived extracellular vesicles promote the cancer progression and angiogenesis by mediating M2 macrophages polarization. J. Ovarian Res. 2024, 17, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.C.; Liao, Y.C.; Chen, P.M.; Yang, Y.Y.; Wang, Y.H.; Tung, S.L.; Chuang, C.M.; Sung, Y.W.; Jang, T.H.; Chuang, S.E.; et al. Periostin promotes ovarian cancer metastasis by enhancing M2 macrophages and cancer-associated fibroblasts via integrin-mediated NF-κB and TGF-β2 signaling. J. Biomed. Sci. 2022, 29, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prat, M.; Le Naour, A.; Coulson, K.; Lemée, F.; Leray, H.; Jacquemin, G.; Rahabi, M.C.; Lemaitre, L.; Authier, H.; Ferron, G.; et al. Circulating CD14high CD16low intermediate blood monocytes as a biomarker of ascites immune status and ovarian cancer progression. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e000472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Ye, B.; Chi, H.; Cheng, C.; Liu, J. Identification of peripheral blood immune infiltration signatures and construction of monocyte-associated signatures in ovarian cancer and Alzheimer’s disease using single-cell sequencing. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villani, A.C.; Satija, R.; Reynolds, G.; Sarkizova, S.; Shekhar, K.; Fletcher, J.; Griesbeck, M.; Butler, A.; Zheng, S.; Lazo, S.; et al. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals new types of human blood dendritic cells, monocytes, and progenitors. Science 2017, 356, eaah4573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapellos, T.S.; Bonaguro, L.; Gemund, I.; Reusch, N.; Saglam, A.; Hinkley, E.R.; Schultze, J.L. Human Monocyte Subsets and Phenotypes in Major Chronic Inflammatory Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loercher, A.E.; Nash, M.A.; Kavanagh, J.J.; Platsoucas, C.D.; Freedman, R.S. Identification of an IL-10-producing HLA-DR-negative monocyte subset in the malignant ascites of patients with ovarian carcinoma that inhibits cytokine protein expression and proliferation of autologous T cells. J. Immunol. 1999, 163, 6251–6260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Wang, X.; Cheng, X.; Liu, Z.; Yin, Y.; Li, X.; Huang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Guo, W.; Ginhoux, F.; et al. Single-cell analyses implicate ascites in remodeling the ecosystems of primary and metastatic tumors in ovarian cancer. Nat. Cancer 2023, 4, 1138–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steitz, A.M.; Steffes, A.; Finkernagel, F.; Unger, A.; Sommerfeld, L.; Jansen, J.M.; Wagner, U.; Graumann, J.; Muller, R.; Reinartz, S. Tumor-associated macrophages promote ovarian cancer cell migration by secreting transforming growth factor beta induced (TGFBI) and tenascin C. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, L.S.; Robinson, M.; Stevenson, D.; Amador, I.C.; Jordan, G.J.; Valencia, S.; Navarrete, C.; House, C.D. Chemotherapy Enriches for Proinflammatory Macrophage Phenotypes that Support Cancer Stem-Like Cells and Disease Progression in Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Res. Commun. 2024, 4, 2638–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, B.; Sarkar, M.; Ghosh, D.; Mishra, S.; Bose, S.; Khan, M.M.A.; Ganesan, S.K.; Chatterjee, N.; Srivastava, A.K. Tumor-associated macrophages contribute to cisplatin resistance via regulating Pol eta-mediated translesion DNA synthesis in ovarian cancer. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2025, 82, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, N.; Wu, W.; Li, H.; Chen, J.; Guo, X. Molecular mechanism of CD163+ tumor-associated macrophage (TAM)-derived exosome-induced cisplatin resistance in ovarian cancer ascites. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreejit, G.; Fleetwood, A.J.; Murphy, A.J.; Nagareddy, P.R. Origins and diversity of macrophages in health and disease. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 2020, 9, e1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, F.O.; Gordon, S. The M1 and M2 paradigm of macrophage activation: Time for reassessment. F1000prime Rep. 2014, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rőszer, T. Understanding the Mysterious M2 Macrophage through Activation Markers and Effector Mechanisms. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 816460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sica, A.; Mantovani, A. Macrophage plasticity and polarization: In vivo veritas. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, P.J.; Allen, J.E.; Biswas, S.K.; Fisher, E.A.; Gilroy, D.W.; Goerdt, S.; Gordon, S.; Hamilton, J.A.; Ivashkiv, L.B.; Lawrence, T.; et al. Macrophage activation and polarization: Nomenclature and experimental guidelines. Immunity 2014, 41, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Galán, L.; Olleros, M.L.; Vesin, D.; Garcia, I. Much more than M1 and M2 macrophages, there are also CD169+ and TCR+ macrophages. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyken, S.J.; Locksley, R.M. Interleukin-4-and interleukin-13-mediated alternatively activated macrophages: Roles in homeostasis and disease. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 31, 317–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Li, G.; Jiang, C.; Hu, J.; Hu, X. Regulatory mechanisms of macrophage polarization in adipose tissue. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1149366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Zhao, F.; Cheng, H.; Su, M.; Wang, Y. Macrophage polarization: An important role in inflammatory diseases. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1352946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweer, D.; McAtee, A.; Neupane, K.; Richards, C.; Ueland, F.; Kolesar, J. Tumor-associated macrophages and ovarian cancer: Implications for therapy. Cancers 2022, 14, 2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Cai, D.J.; Li, B. Ovarian cancer stem-like cells elicit the polarization of M2 macrophages. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 11, 4685–4693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Li, S.; To, K.K.; Zhu, S.; Wang, F.; Fu, L. Tumor-associated macrophages remodel the suppressive tumor immune microenvironment and targeted therapy for immunotherapy. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 44, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerneur, C.; Cano, C.E.; Olive, D. Major pathways involved in macrophage polarization in cancer. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1026954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Xiao, M.; Cao, G.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Zijtveld, S.; Delvoux, B.; Xanthoulea, S.; Romano, A.; et al. Human monocytes differentiate into tumor-associated macrophages upon SKOV3 cells coculture and/or lysophosphatidic acid stimulation. J. Inflamm. 2022, 19, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; He, Y.; Sun, X.; Li, Q.; Wang, W.; Zhao, A.; Di, W. A high M1/M2 ratio of tumor-associated macrophages is associated with extended survival in ovarian cancer patients. J. Ovarian Res. 2014, 7, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macciò, A.; Gramignano, G.; Cherchi, M.C.; Tanca, L.; Melis, L.; Madeddu, C. Role of M1-polarized tumor-associated macrophages in the prognosis of advanced ovarian cancer patients. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisoni, E.; Benedetti, F.; Minasyan, A.; Desbuisson, M.; Cunnea, P.; Grimm, A.J.; Fahr, N.; Capt, C.; Rayroux, N.; De Carlo, F.; et al. Myeloid cell networks govern re-establishment of original immune landscapes in recurrent ovarian cancer. Cancer Cell 2025, 43, 1568–1586.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Chen, J.; Tan, M.; Tan, Q. The role of macrophage polarization in ovarian cancer: From molecular mechanism to therapeutic potentials. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1543096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Bian, Z.; Liu, Y. Dual role of SIRPα in macrophage activation: Inhibiting M1 while promoting M2 polarization via selectively activating SHP-1 and SHP-2 signal. J. Immunol. 2017, 198, 67.12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binnewies, M.; Pollack, J.L.; Rudolph, J.; Dash, S.; Abushawish, M.; Lee, T.; Jahchan, N.S.; Canaday, P.; Lu, E.; Norng, M.; et al. Targeting TREM2 on tumor-associated macrophages enhances immunotherapy. Cell Rep. 2021, 37, 109844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.; Wang, C.-X.; Ou, Z.-Y. TGF-β1 and IL-10 expression in epithelial ovarian cancer cell line A2780. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2015, 14, 2179–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarkowski, R.; Polak, G.; Wertel, I.; Kotarska, M. Evaluation of IL-10 and TGF-beta levels and myeloid and lymphoid dendritic cells in ovarian cancer patients. Ginekol. Pol. 2011, 82, 446324. Available online: https://journals.viamedica.pl/ginekologia_polska/article/view/46324/33111 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Zhang, L.; Liu, W.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Sun, H. Prognostic value of serum IL-8 and IL-10 in patients with ovarian cancer undergoing chemotherapy. Oncol. Lett. 2019, 17, 2365–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Luo, F.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, W.; Xiang, T.; Pan, Q.; Cai, L.; Zhao, J.; Weng, D.; Li, Y.; et al. CircITGB6 promotes ovarian cancer cisplatin resistance by resetting tumor-associated macrophage polarization toward the M2 phenotype. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e004029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Yin, Q.; Wu, Z.; Li, W.; Huang, J.; Chen, B.; Yang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Zeng, L.; Wang, J. Inflammation and Immune Escape in Ovarian Cancer: Pathways and Therapeutic Opportunities. J. Inflamm. Res. 2025, 18, 895–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauneck, F.; Oliveira-Ferrer, L.; Muschhammer, J.; Sturmheit, T.; Ackermann, C.; Haag, F.; Schulze zur Wiesch, J.; Ding, Y.; Qi, M.; Hell, L.; et al. Immunosuppressive M2 TAMs represent a promising target population to enhance phagocytosis of ovarian cancer cells in vitro. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1250258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ma, C.; Li, X.; Yang, F.; Wang, N.; Ji, G.; Liu, Q.; Zhu, H.; Xu, S.; Li, H. Unraveling the role of M2 TAMs in ovarian cancer dynamics: A systematic review. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, J.; Li, Z.; Lin, C.; Wang, D.; Yu, L.; Xiao, X. The role of circRNAs in regulation of drug resistance in ovarian cancer. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1320185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, V.; Tallapragada, S.; Schaar, B.; Kamat, K.; Chanana, A.M.; Zhang, Y.; Patel, S.; Parkash, V.; Rinker-Schaeffer, C.; Folkins, A.K.; et al. Omental macrophages secrete chemokine ligands that promote ovarian cancer colonization of the omentum via CCR1. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallapragada, S.; Chan, J.; Krishnan, V.; Dorigo, O. Abstract 6810: Macrophage secreted CCL9/CCL5 induces CCR1-mediated ovarian cancer metastasis to the omentum in the absence of CCL6. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, 6810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, C.; Huang, X.; Lin, S.; Huang, H.; Cai, Q.; Wan, T.; Lu, J.; Liu, J. Expression of M2-polarized macrophages is associated with poor prognosis for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2013, 12, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, D.; Mao, Y.; Mo, F.; Du, W.; Ma, X. Prognostic significance of tumor-associated macrophages in ovarian cancer: A meta-analysis. Gynecol. Oncol. 2017, 147, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hume, D.A. Macrophages as APC and the dendritic cell myth. J. Immunol. 2008, 181, 5829–5835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shortman, K.; Liu, Y.-J. Mouse and human dendritic cell subtypes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002, 2, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudziak, D.; Kamphorst, A.O.; Heidkamp, G.F.; Buchholz, V.R.; Trumpfheller, C.; Yamazaki, S.; Cheong, C.; Liu, K.; Lee, H.-W.; Park, C.G.; et al. Differential antigen processing by dendritic cell subsets in vivo. Science 2007, 315, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reizis, B.; Bunin, A.; Ghosh, H.S.; Lewis, K.L.; Sisirak, V. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells: Recent progress and open questions. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 29, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanova, D.Y.; Moroz, L.L. The ancestral architecture of the immune system in simplest animals. Front. Immunol. 2025, 15, 1529836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Upadhyay, R.; Pokrovskii, M.; Chen, F.M.; Romero-Meza, G.; Griesemer, A.; Littman, D.R. Prdm16-dependent antigen-presenting cells induce tolerance to gut antigens. Nature 2025, 642, 756–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collin, M.; Bigley, V. Monocyte, macrophage, and dendritic cell development: The human perspective. In Myeloid Cells in Health and Disease: A Synthesis; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brencicova, E.; Jagger, A.L.; Evans, H.G.; Georgouli, M.; Laios, A.; Attard Montalto, S.; Mehra, G.; Spencer, J.; Ahmed, A.A.; Raju-Kankipati, S.; et al. Interleukin-10 and prostaglandin E2 have complementary but distinct suppressive effects on Toll-like receptor-mediated dendritic cell activation in ovarian carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyne, H.E.; Stone, P.J.; Burnett, A.F.; Cannon, M.J. Ovarian tumor ascites CD14+ cells suppress dendritic cell-activated CD4+ T-cell responses through IL-10 secretion and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. J. Immunother. 2014, 37, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broz, M.L.; Binnewies, M.; Boldajipour, B.; Nelson, A.E.; Pollack, J.L.; Erle, D.J.; Barczak, A.; Rosenblum, M.D.; Daud, A.; Barber, D.L.; et al. Dissecting the tumor myeloid compartment reveals rare activating antigen-presenting cells critical for T cell immunity. Cancer Cell 2014, 26, 638–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Paulete, A.R.; Teijeira, A.; Cueto, F.J.; Garasa, S.; Perez-Gracia, J.L.; Sanchez-Arraez, A.; Sancho, D.; Melero, I. Antigen cross-presentation and T-cell cross-priming in cancer immunology and immunotherapy. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, xii74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caro, A.A.; Deschoemaeker, S.; Allonsius, L.; Coosemans, A.; Laoui, D. Dendritic Cell Vaccines: A Promising Approach in the Fight against Ovarian Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 4037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgdorf, S.; Porubsky, S.; Marx, A.; Popovic, Z.V. Cancer Acidity and Hypertonicity Contribute to Dysfunction of Tumor-Associated Dendritic Cells: Potential Impact on Antigen Cross-Presentation Machinery. Cancers 2020, 12, 2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labidi-Galy, S.I.; Treilleux, I.; Goddard-Leon, S.; Combes, J.D.; Blay, J.Y.; Ray-Coquard, I.; Caux, C.; Bendriss-Vermare, N. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells infiltrating ovarian cancer are associated with poor prognosis. Oncoimmunology 2012, 1, 380–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, C.; Rampf, E.; Toth, B.; Brunnhuber, R.; Weissenbacher, T.; Friese, K.; Jeschke, U. Ovarian cancer-derived glycodelin impairs in vitro dendritic cell maturation. J. Immunother. 2009, 32, 492–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawlowska, A.; Kwiatkowska, A.; Suszczyk, D.; Chudzik, A.; Tarkowski, R.; Barczynski, B.; Kotarski, J.; Wertel, I. Clinical and Prognostic Value of Antigen-Presenting Cells with PD-L1/PD-L2 Expression in Ovarian Cancer Patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surowka, J.; Wertel, I.; Okla, K.; Bednarek, W.; Tarkowski, R.; Kotarski, J. Influence of ovarian cancer type I and type II microenvironment on the phenotype and function of monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2017, 19, 1489–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Curiel, T.J.; Coukos, G.; Zou, L.; Alvarez, X.; Cheng, P.; Mottram, P.; Evdemon-Hogan, M.; Conejo-Garcia, J.R.; Zhang, L.; Burow, M.; et al. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, 942–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Kryczek, I.; Zou, L.; Daniel, B.; Cheng, P.; Mottram, P.; Curiel, T.; Lange, A.; Zou, W. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells induce CD8+ regulatory T cells in human ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 5020–5026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, C.; Gregorio, J.; Wang, Y.H.; Ito, T.; Meller, S.; Hanabuchi, S.; Anderson, S.; Atkinson, N.; Ramirez, P.T.; Liu, Y.J.; et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells promote immunosuppression in ovarian cancer via ICOS costimulation of Foxp3+ T-regulatory cells. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 5240–5249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conejo-Garcia, J.R.; Benencia, F.; Courreges, M.C.; Kang, E.; Mohamed-Hadley, A.; Buckanovich, R.J.; Holtz, D.O.; Jenkins, A.; Na, H.; Zhang, L.; et al. Tumor-infiltrating dendritic cell precursors recruited by a beta-defensin contribute to vasculogenesis under the influence of Vegf-A. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, 950–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veglia, F.; Sanseviero, E.; Gabrilovich, D.I. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the era of increasing myeloid cell diversity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talmadge, J.E.; Gabrilovich, D.I. History of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2013, 13, 739–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veglia, F.; Perego, M.; Gabrilovich, D. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells coming of age. Nat. Immunol. 2018, 19, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, Y.; Cheng, D.; Jia, Q.; Xiong, H.; Zhang, J. Mechanisms Underlying the Role of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in Clinical Diseases: Good or Bad. Immune Netw. 2021, 21, e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groth, C.; Hu, X.; Weber, R.; Fleming, V.; Altevogt, P.; Utikal, J.; Umansky, V. Immunosuppression mediated by myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) during tumour progression. Br. J. Cancer 2019, 120, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehn, B.H.; Apostolova, P.; Haverkamp, J.M.; Miller, J.S.; McCullar, V.; Tolar, J.; Munn, D.H.; Murphy, W.J.; Brickey, W.J.; Serody, J.S.; et al. GVHD-associated, inflammasome-mediated loss of function in adoptively transferred myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Blood 2015, 126, 1621–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yang, K.; Pang, L.; Fei, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, J. ANKRD22 is a potential novel target for reversing the immunosuppressive effects of PMN-MDSCs in ovarian cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e005527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabuchi, S.; Sasano, T.; Komura, N. Targeting Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in Ovarian Cancer. Cells 2021, 10, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taki, M.; Abiko, K.; Baba, T.; Hamanishi, J.; Yamaguchi, K.; Murakami, R.; Yamanoi, K.; Horikawa, N.; Hosoe, Y.; Nakamura, E.; et al. Snail promotes ovarian cancer progression by recruiting myeloid-derived suppressor cells via CXCR2 ligand upregulation. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obermajer, N.; Muthuswamy, R.; Odunsi, K.; Edwards, R.P.; Kalinski, P. PGE2-induced CXCL12 production and CXCR4 expression controls the accumulation of human MDSCs in ovarian cancer environment. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 7463–7470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Deng, Z.; Peng, Y.; Han, L.; Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Li, B.; Zhao, J.; Jiao, S.; Wei, H. Ascites-derived IL-6 and IL-10 synergistically expand CD14+HLA-DR-/low myeloid-derived suppressor cells in ovarian cancer patients. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 76843–76856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horikawa, N.; Abiko, K.; Matsumura, N.; Hamanishi, J.; Baba, T.; Yamaguchi, K.; Yoshioka, Y.; Koshiyama, M.; Konishi, I. Expression of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor in Ovarian Cancer Inhibits Tumor Immunity through the Accumulation of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 587–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okla, K.; Czerwonka, A.; Wawruszak, A.; Bobinski, M.; Bilska, M.; Tarkowski, R.; Bednarek, W.; Wertel, I.; Kotarski, J. Clinical Relevance and Immunosuppressive Pattern of Circulating and Infiltrating Subsets of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells (MDSCs) in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, J.; Wu, W.; Gao, H.; Liu, N.; Zhan, G.; Li, L.; Han, L.; Guo, X. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells promote epithelial ovarian cancer cell stemness by inducing the CSF2/p-STAT3 signalling pathway. FEBS J. 2020, 287, 5218–5235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komura, N.; Mabuchi, S.; Shimura, K.; Yokoi, E.; Kozasa, K.; Kuroda, H.; Takahashi, R.; Sasano, T.; Kawano, M.; Matsumoto, Y.; et al. The role of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in increasing cancer stem-like cells and promoting PD-L1 expression in epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2020, 69, 2477–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, M.; Zhang, P.; Huang, L.; Ai, X.; Yang, Z.; Shen, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, P.; et al. Suppressing MDSC Infiltration in Tumor Microenvironment Serves as an Option for Treating Ovarian Cancer Metastasis. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 3697–3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okla, K. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells (MDSCs) in Ovarian Cancer-Looking Back and Forward. Cells 2023, 12, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, K.P.; Gluck, L.; Martin, L.P.; Olszanski, A.J.; Tolcher, A.W.; Ngarmchamnanrith, G.; Rasmussen, E.; Amore, B.M.; Nagorsen, D.; Hill, J.S.; et al. First-in-human study of AMG 820, a monoclonal anti-colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor antibody, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 5703–5710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negus, R.P.; Stamp, G.W.; Hadley, J.; Balkwill, F.R. Quantitative assessment of the leukocyte infiltrate in ovarian cancer and its relationship to the expression of C-C chemokines. Am. J. Pathol. 1997, 150, 1723–1734. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, T.; Mitamura, T.; Wang, L.; Kubota, S.I.; Murakami, M.; Tanaka, S.; Watari, H. Combination therapy with bevacizumab and a CCR2 inhibitor for human ovarian cancer: An in vivo validation study. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 9697–9708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, S.K.; Papadopoulos, K.; Fong, P.C.; Patnaik, A.; Messiou, C.; Olmos, D.; Wang, G.; Tromp, B.J.; Puchalski, T.A.; Balkwill, F.; et al. A first-in-human, first-in-class, phase I study of carlumab (CNTO 888), a human monoclonal antibody against CC-chemokine ligand 2 in patients with solid tumors. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2013, 71, 1041–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pienta, K.J.; Machiels, J.P.; Schrijvers, D.; Alekseev, B.; Shkolnik, M.; Crabb, S.J.; Li, S.; Seetharam, S.; Puchalski, T.A.; Takimoto, C.; et al. Phase 2 study of carlumab (CNTO 888), a human monoclonal antibody against CC-chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2), in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Investig. New Drugs 2013, 31, 760–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikeghbal, P.; Burke, D.; Armijo, D.; Aldarondo-Quinones, S.; Lidke, D.S.; Steinkamp, M.P. The Influence of Macrophages within the Tumor Microenvironment on Ovarian Cancer Growth and Response to Therapies. bioRxiv 2025, bioRxiv 2025.01.29.635532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhani, N.J.; Stewart, D.; Richardson, D.L.; Dockery, L.E.; Van Le, L.; Call, J.; Rangwala, F.; Wang, G.; Ma, B.; Metenou, S.; et al. First-in-human phase I trial of the bispecific CD47 inhibitor and CD40 agonist Fc-fusion protein, SL-172154 in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, e010565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Zuo, D.; Xu, J.; Feng, Y.; Xue, D.; Zhang, L.; Lin, L.; Zhang, J. A clinical study of autologous chimeric antigen receptor macrophage targeting mesothelin shows safety in ovarian cancer therapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 17, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeku, O.O.; Barve, M.; Tan, W.W.; Wang, J.; Patnaik, A.; LoRusso, P.; Richardson, D.L.; Naqash, A.R.; Lynam, S.K.; Fu, S.; et al. Myeloid targeting antibodies PY159 and PY314 for platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, e010959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattan, R.; Dar, S.; Rasool, N.; Ali-Fehmi, R.; Giri, S.; Munkarah, A.R. Depletion of immunosuppressive myeloid-derived suppressor cells impedes ovarian cancer growth. Gynecol. Oncol. 2017, 145, 213–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udumula, M.P.; Sakr, S.; Dar, S.; Alvero, A.B.; Ali-Fehmi, R.; Abdulfatah, E.; Li, J.; Jiang, J.; Tang, A.; Buekers, T.; et al. Ovarian cancer modulates the immunosuppressive function of CD11b+Gr1+ myeloid cells via glutamine metabolism. Mol. Metab. 2021, 53, 101272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Fan, Z.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Yue, D.; Qin, G.; Zhang, T.; et al. Metformin-Induced Reduction of CD39 and CD73 Blocks Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cell Activity in Patients with Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 1779–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soong, R.S.; Anchoori, R.K.; Yang, B.; Yang, A.; Tseng, S.H.; He, L.; Tsai, Y.C.; Roden, R.B.; Hung, C.F. RPN13/ADRM1 inhibitor reverses immunosuppression by myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 68489–68502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Alexander, E.T.; Minton, A.R.; Peters, M.C.; van Ryn, J.; Gilmour, S.K. Thrombin inhibition and cisplatin block tumor progression in ovarian cancer by alleviating the immunosuppressive microenvironment. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 85291–85305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, K.M.; Byrne, K.T.; Molloy, M.J.; Usherwood, E.M.; Berwin, B. IL-10 immunomodulation of myeloid cells regulates a murine model of ovarian cancer. Front. Immunol. 2011, 2, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandalaft, L.E.; Chiang, C.L.; Tanyi, J.; Motz, G.; Balint, K.; Mick, R.; Coukos, G. A Phase I vaccine trial using dendritic cells pulsed with autologous oxidized lysate for recurrent ovarian cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2013, 11, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rob, L.; Cibula, D.; Knapp, P.; Mallmann, P.; Klat, J.; Minar, L.; Bartos, P.; Chovanec, J.; Valha, P.; Pluta, M.; et al. Safety and efficacy of dendritic cell-based immunotherapy DCVAC/OvCa added to first-line chemotherapy (carboplatin plus paclitaxel) for epithelial ovarian cancer: A phase 2, open-label, multicenter, randomized trial. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e003190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cibula, D.; Rob, L.; Mallmann, P.; Knapp, P.; Klat, J.; Chovanec, J.; Minar, L.; Melichar, B.; Hein, A.; Kieszko, D.; et al. Dendritic cell-based immunotherapy (DCVAC/OvCa) combined with second-line chemotherapy in platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer (SOV02): A randomized, open-label, phase 2 trial. Gynecol. Oncol. 2021, 162, 652–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.M.; Bast, R.C., Jr. Early detection of ovarian cancer. Biomark. Med. 2008, 2, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Siu, M.K.Y.; Ngan, H.Y.S.; Chan, K.K.L. Molecular Biomarkers for the Early Detection of Ovarian Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenzel, A.E.; Abrams, S.I.; Joseph, J.M.; Goode, E.L.; Tario, J.D., Jr.; Wallace, P.K.; Kaur, D.; Adamson, A.K.; Buas, M.F.; Lugade, A.A.; et al. Circulating CD14+ HLA-DRlo/- monocytic cells as a biomarker for epithelial ovarian cancer progression. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2021, 85, e13343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soibi-Harry, A.P.; Amaeshi, L.C.; Garba, S.R.; Anorlu, R.I. The relationship between pre-operative lymphocyte to monocyte ratio and serum cancer antigen-125 among women with epithelial ovarian cancer in Lagos, Nigeria. ecancermedicalscience 2021, 15, 1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Shen, G.; Li, Y.; Xie, Y.; Ma, X.; Jiang, L.; Lv, Q. Lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio after primary surgery is an independent prognostic factor for patients with epithelial ovarian cancer: A propensity score matching analysis. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1139929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chetrit, A.; Hirsh-Yechezkel, G.; Ben-David, Y.; Lubin, F.; Friedman, E.; Sadetzki, S. Effect of BRCA1/2 mutations on long-term survival of patients with invasive ovarian cancer: The national Israeli study of ovarian cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greten, F.R.; Grivennikov, S.I. Inflammation and cancer: Triggers, mechanisms, and consequences. Immunity 2019, 51, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Jiang, H.; Shu, C.; Hu, M.-q.; Huang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Li, R.-f. Prognostic value of lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio in ovarian cancer: A meta-analysis. J. Ovarian Res. 2019, 12, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Åstrand, A.; Wingren, C.; Walton, C.; Mattsson, J.; Agrawal, K.; Lindqvist, M.; Odqvist, L.; Burmeister, B.; Eck, S.; Hughes, G.; et al. A comparative study of blood cell count in four automated hematology analyzers: An evaluation of the impact of preanalytical factors. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0301845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulati, G.; Uppal, G.; Gong, J. Unreliable automated complete blood count results: Causes, recognition, and resolution. Ann. Lab. Med. 2022, 42, 515–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiak, A.; Ziółkowska, E.; Korycka-Wołowiec, A. The diagnostic pitfalls and challenges associated with basic hematological tests. Acta Haematol. Pol. 2022, 53, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanzad, M.; Hajian-Tilaki, K. Methods of determining optimal cut-point of diagnostic biomarkers with application of clinical data in ROC analysis: An update review. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2024, 24, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc-Durand, F.; Clemence Wei Xian, L.; Tan, D.S. Targeting the immune microenvironment for ovarian cancer therapy. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1328651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, K.; Alexander, C.; Webb, J.R.; Sun, W.; Dillon, K.; Kalloger, S.E.; Gilks, C.B.; Clarke, B.; Köbel, M.; Nelson, B.H. Absolute lymphocyte count is associated with survival in ovarian cancer independent of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. J. Transl. Med. 2012, 10, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salima, S.; Sampeliling, D.G.; Permadi, W.; Sasotya, R.S.; Aziz, M.A.; Kurniadi, A.; Nisa, A.S. Analysis of inflammation parameter value lymphocyte monocyte ratio (LMR), platelet lymphocyte ratio (PLR), and systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) to differentiate malignant and benign ovarian tumors. BMC Res. Notes 2025, 18, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Yang, L.; Liu, D.; Li, W.M. Prognostic value of pretreatment lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio in lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2021, 20, 1533033820983085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, P.; Huang, L.; Lin, L.; Chen, Y.; Guo, X. The prognostic utility of the ratio of lymphocyte to monocyte in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1394154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Zhou, L.; Ouyang, J.; Yang, H. Prognostic value of lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio in ovarian cancer: A meta-analysis. Medicine 2019, 98, e15876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, L.; Song, Y.; Zhao, X. Prognostic significance of lymphocyte monocyte ratio in patients with ovarian cancer. Medicine 2020, 99, e19638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Hu, H.; Tang, F.; Lin, D.; Shen, R.; Deng, L.; Tang, Y.; Deng, L.; Zhou, M.; Li, J.; et al. Combined preoperative LMR and CA125 for prognostic assessment of ovarian cancer. J. Cancer 2020, 11, 3165–3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, M.J.; Yoon, Y.N.; Kang, Y.K.; Kim, C.J.; Nam, H.S.; Lee, Y.S. A novel score using lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio in blood and malignant body fluid for predicting prognosis of patients with advanced ovarian cancer. Cancers 2023, 15, 2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaja, A.; Teruel, I.; Ochoa-de-Olza, M.; Cucurull, M.; Arroyo, Á.J.; Pardo, B.; Ortiz, I.; Gil-Martin, M.; Piulats, J.M.; Pla, H.; et al. Prognostic role of neutrophil, monocyte and platelet to lymphocyte ratios in advanced ovarian cancer according to the time of debulking surgery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cell Type | Physiological Functions/ Introduction | Recruitment/ Differentiation in OC | Immunosuppressive Roles | Contribution to Chemoresistance | Contribution to Metastasis | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monocytes |

|

|

|

|

| [9,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52] |

| Macrophages |

|

|

|

|

| [25,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84] |

| DCs |

|

|

|

|

| [85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105] |

| MDSCs |

|

|

|

|

| [48,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122] |

| Cell Type | Therapeutic Strategy | Key Findings | Evidence Type | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monocyte | Blocking Monocyte Recruitment: CSF-1/CSF-1R axis |

| Preclinical + Clinical (NCT01444404) (NCT02713529) | [9,16,123] |

| Blocking Monocyte Recruitment: CCL2/CCR2 axis |

| Preclinical + Clinical (NCT00537368) | [124,125,126,127] | |

| Macrophage | Macrophage Reprogramming: M2 → M1 phenotype |

| Preclinical | [17,70,128] |

| Dual CD47 blockade + CD40 agonism (SL-172154) |

| Clinical (NCT04406623) | [129] | |

| CAR-Macrophage (CAR-M) Therapy |

| Clinical (NCT06562647) | [130] | |

| TREM-2 Targeting (PY159, PY314) |

| Early Clinical (NCT04682431) (NCT04691375) | [131] | |

| MDSCs | Targeting MDSCs: Depletion |

| Preclinical | [132,133] |

| Targeting MDSCs: Functional Inhibition |

| Preclinical | [134,135,136] | |

| Targeting MDSCs: Recruitment Blockade |

| Preclinical | [113,114] | |

| Targeting MDSCs: Differentiation Induction | Blocking IL-10 signalling reprogrammed MDSCs, boosted T-cell activity, and prolonged survival. | Preclinical | [137] | |

| DCs | Dendritic Cell Vaccine (DCVAC/OvCa) |

| Clinical (NCT02107937) (NCT02107950) | [138,139] |

| Study Design [Ref.] | Sample Size | Prognostic Markers Studied | Primary Outcomes | LMR/MLR Cutoff Value(s) | OS Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | PFS Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | Marker Type | Survival Impact | Disease Stage Association | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meta-analysis [20] | 3346 patients from 12 studies | LMR | OS, PFS | Ranged from 1.85 to 4.35 | 1.85 (1.50–2.28) for high vs. low LMR | 1.70 (1.49–1.94) for high vs. low LMR | Prognostic | High LMR is favourable. Stronger association in patients of <55 years. | Higher pretreatment LMR is associated with more favourable outcomes among all stages and subtypes of EOC/OC patients, and stronger associations for younger patients than older patients. | LMR is a simple, cost-effective prognostic biomarker. Future prospective trials are needed. |

| Meta-analysis [148] | 2259 patients from 8 studies | LMR | OS, PFS, Clinicopathological features | Ranged from 1.85 to 4.2 | 1.92 (1.58–2.34) for low vs. high LMR | 1.70 (1.54–1.88) for low vs. high LMR | Prognostic, correlative | Low LMR indicates a poor prognosis. | Low LMR is significantly associated with advanced FIGO stage (III–IV), higher tumour grade (G2/G3), lymph node metastasis, and malignant ascites. | Pre-treatment LMR is a potential marker of poor outcome and is correlated with aggressive tumour characteristics. |

| Meta-analysis [158] | 2343 patients from 7 studies | LMR/MLR | OS, PFS, Clinicopathological parameters | Ranged from 2.22 to 4.35 | 1.81 (1.38–2.37) for low vs. high LMR | 1.65 (1.46–1.85) for low vs. high LMR | Prognostic, correlative | Low LMR is associated with unfavourable survival. | Low LMR is significantly associated with advanced FIGO stage, lymph node metastasis, larger residual tumour, and higher CA-125 levels. | LMR could serve as a promising prognostic biomarker, particularly in China. |

| Meta-analysis [159] | 2809 patients from 9 studies | LMR | OS, PFS | Ranged from 1.85 to 4.35 | 1.71 (1.40–2.09) for low vs. high LMR | 1.68 (1.49–1.88) for low vs. high LMR | Prognostic | Lower LMR is associated with poorer OS and PFS. | Association is significant in both early and advanced stage disease groups. | LMR is a cheap and readily accessible prognostic tool. May assist in research on therapies modulating host immune response. |

| Retrospective Cohort [160] | 214 | LMR, CA-125, COLC (LMR + CA-125) | OS, PFS | LMR: 3.8 | Low LMR: HR = 0.459 (0.306–0.688) (protective effect of high LMR) | Low LMR: HR = 0.494 (0.329–0.742) (protective effect of high LMR) | Prognostic | Low LMR and high CA-125 are independent predictors of poor OS and PFS. | Not specified | Combining LMR with CA-125 (COLC) improves prognostic specificity for mortality compared to either marker alone. |

| Retrospective Study [161] | 92 patients with advanced OC | LMR in blood (bLMR), LMR in malignant fluid (mLMR) | PFS | bLMR: 2.80; mLMR: 2.41 | Not studied | Low bLMR and low mLMR were independently associated with poor PFS. | Prognostic | Low values in both blood and malignant body fluids (ascites, pleural effusion) are associated with a poor prognosis. | Study limited to advanced stage (III–IV) OC | This is the first study validating the clinical value of LMR in malignant body fluids. A combined score (bmLMR) is a better predictor of recurrence. |

| Retrospective Cohort with PSM [145] | 368 (matched to 111 vs. 111) | LMR | OS | LMR: 4.65 | Low LMR: HR = 1.49 (p = 0.041) (increased risk for low LMR) | Not studied | Prognostic | Low preoperative LMR is an independent factor for poor OS after primary surgery. | Low LMR is significantly correlated with advanced FIGO stage, presence of ascites, and poor differentiation. | Low LMR had a noticeable negative effect in younger patients (<65) and those with aggressive tumours. Completing chemotherapy is crucial for low-LMR patients. |

| Retrospective Cohort [162] | 146 (61 PDS, 85 IDS) | NLR, MLR, PLR | OS, PFS | MLR: 0.4 | Not significant | Not significant | Prognostic (in different surgical settings) | In this study of Caucasian patients, MLR was not a significant prognostic factor in either the PDS or IDS groups. | Study limited to advanced stage (III–IV) OC | The timing of surgery may modulate the prognostic impact of inflammatory markers. High NLR and PLR were prognostic in the PDS group, but not the IDS group. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Balan, D.; Kampan, N.C.; Shafiee, M.N.; Plebanski, M.; Abd Aziz, N.H. Targeting Monocytes and Their Derivatives in Ovarian Cancer: Opportunities for Innovation in Prognosis and Therapy. Cancers 2026, 18, 336. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020336

Balan D, Kampan NC, Shafiee MN, Plebanski M, Abd Aziz NH. Targeting Monocytes and Their Derivatives in Ovarian Cancer: Opportunities for Innovation in Prognosis and Therapy. Cancers. 2026; 18(2):336. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020336

Chicago/Turabian StyleBalan, Dharvind, Nirmala Chandralega Kampan, Mohamad Nasir Shafiee, Magdalena Plebanski, and Nor Haslinda Abd Aziz. 2026. "Targeting Monocytes and Their Derivatives in Ovarian Cancer: Opportunities for Innovation in Prognosis and Therapy" Cancers 18, no. 2: 336. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020336

APA StyleBalan, D., Kampan, N. C., Shafiee, M. N., Plebanski, M., & Abd Aziz, N. H. (2026). Targeting Monocytes and Their Derivatives in Ovarian Cancer: Opportunities for Innovation in Prognosis and Therapy. Cancers, 18(2), 336. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020336