Conversational AI-Enabled Precision Oncology Reveals Context-Dependent MAPK Pathway Alterations in Hispanic/Latino and Non-Hispanic White Colorectal Cancer Stratified by Age and FOLFOX Exposure

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Provenance

2.2. Population Stratification and Clinical Subgroup Definitions

2.3. Treatment Exposure Annotation and FOLFOX Classification

2.4. MAPK Pathway Curation and Genomic Alteration Assessment

2.5. Statistical Analyses

2.6. Conversational AI-Enabled Integration and Analytic Workflow

3. Results

3.1. Cohort Composition and Baseline Clinical Characteristics

3.2. Clinical and Genomic Stratification

3.2.1. Hispanic/Latino CRC by Age of Onset and FOLFOX Exposure

3.2.2. Age-, Treatment-, and MAPK-Specific Genomic Patterns in Non-Hispanic White Patients

3.2.3. Ancestry-Specific Genomic Features in Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer by Treatment Context

3.3. Distribution of MAPK Pathway Alterations Across Age, Ancestry, and Chemotherapy Context

3.3.1. Age- and Treatment-Specific Patterns Within Ancestry Groups

3.3.2. Ancestry-Based Comparisons Within Age and Treatment Strata

3.3.3. Interpretation and Integration with Gene-Level Findings

3.4. Gene-Level Landscape of MAPK Pathway Alterations Across Age, Ancestry, and FOLFOX Exposure

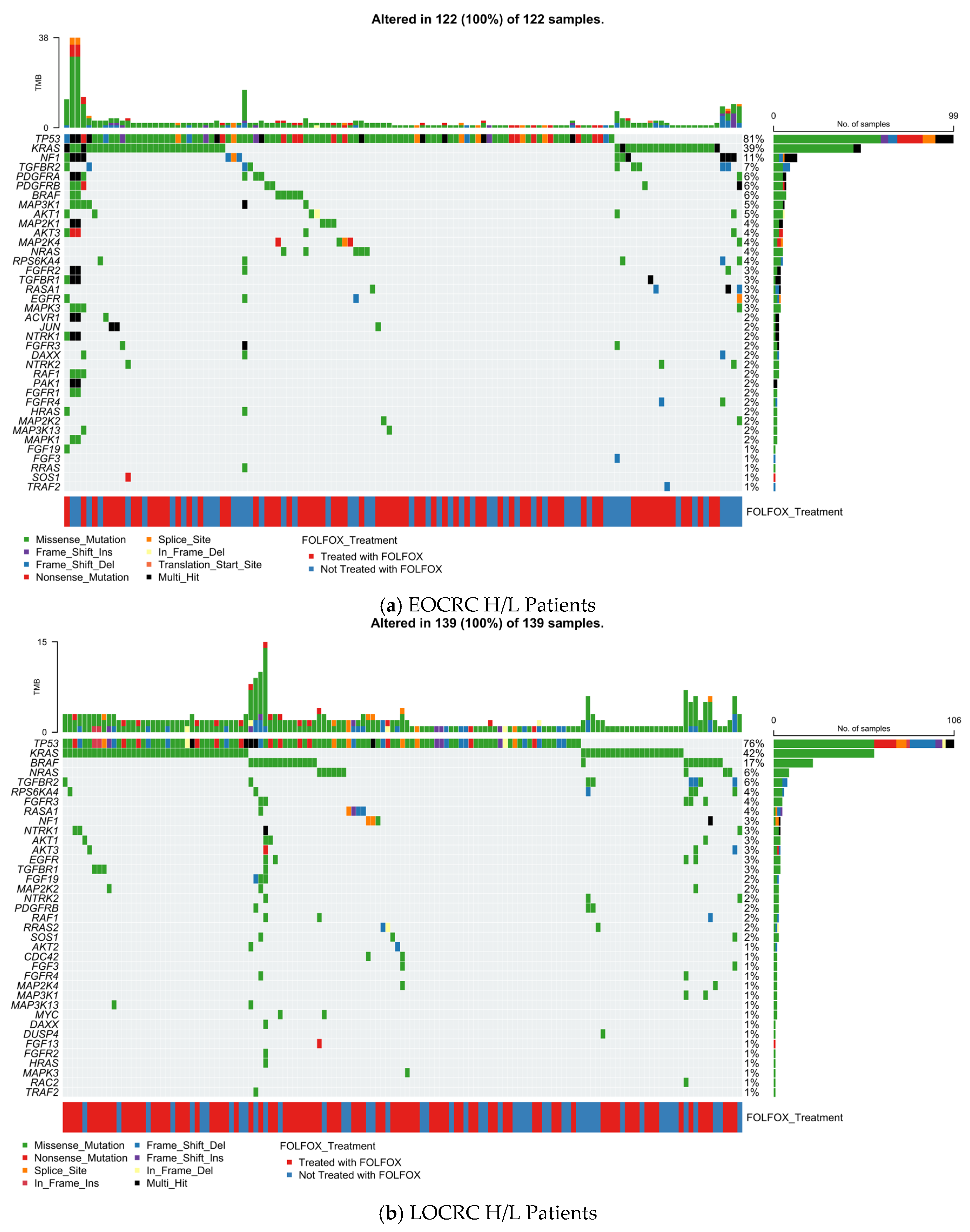

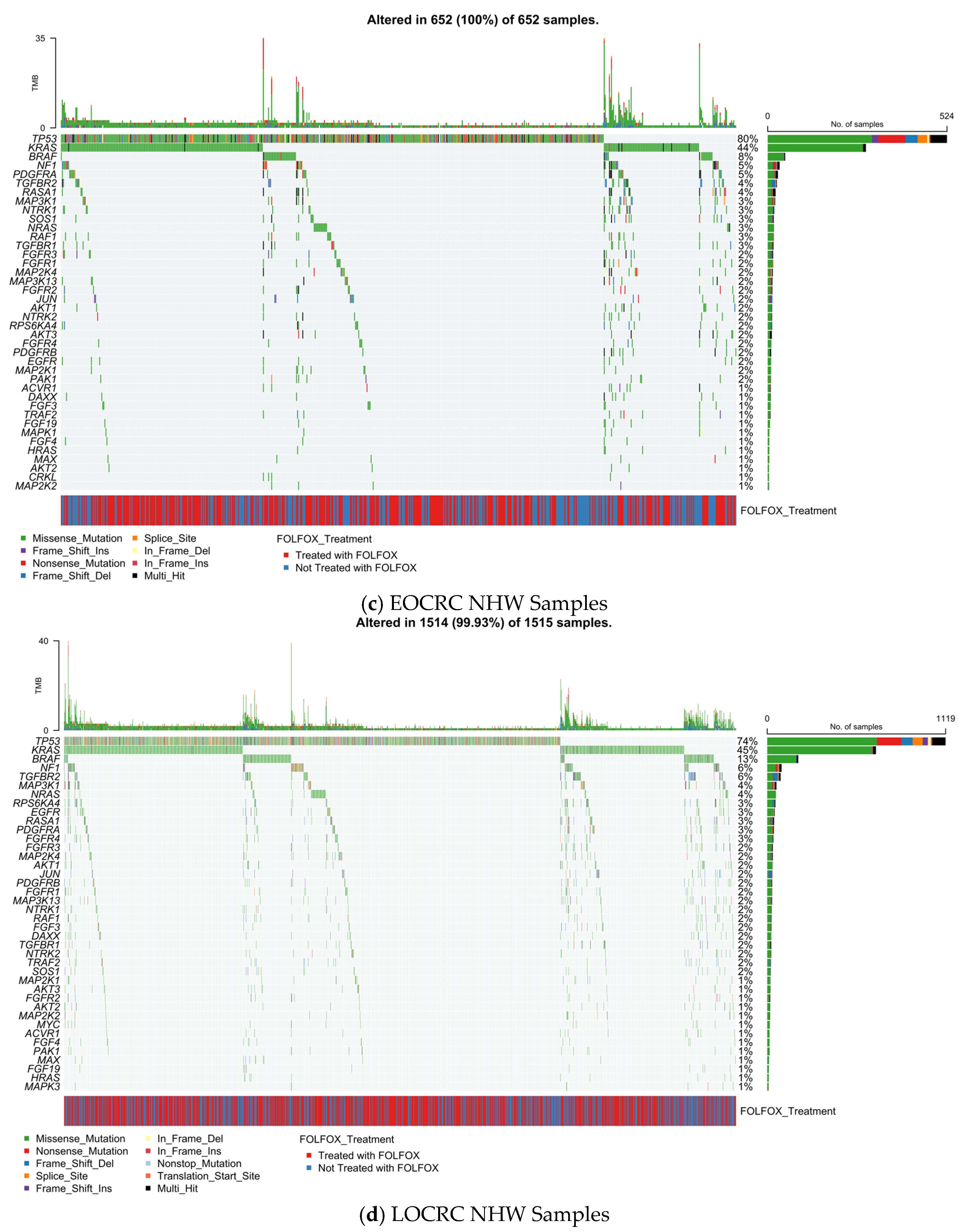

3.5. MAPK Pathway Mutation Profile

3.5.1. Early-Onset Hispanic/Latino Colorectal Cancer

3.5.2. Late-Onset Hispanic/Latino CRC

3.5.3. Early-Onset Non-Hispanic White CRC

3.5.4. Late-Onset Non-Hispanic White CRC

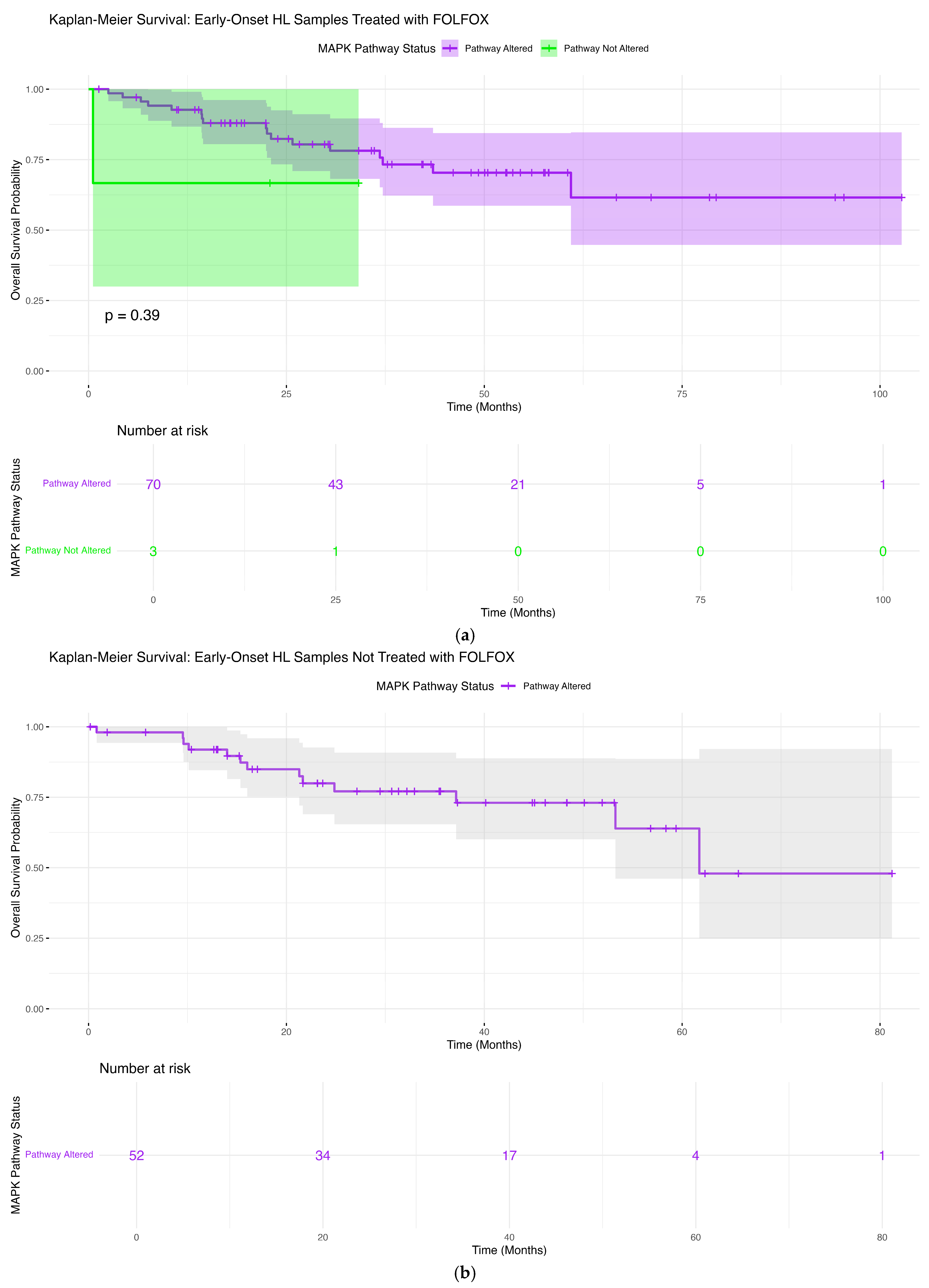

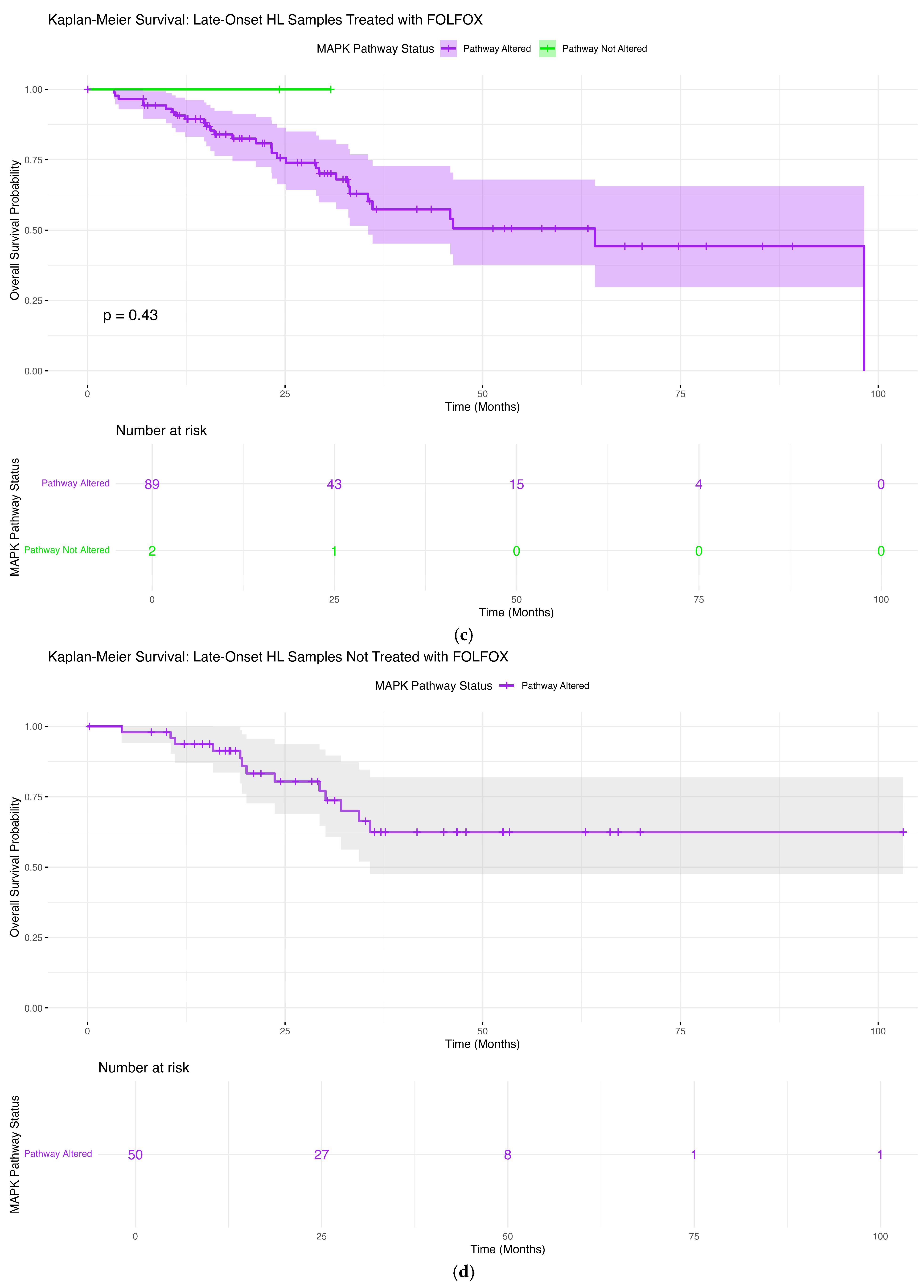

3.6. Survival Associations of MAPK Pathway Alterations

3.6.1. Early-Onset Hispanic/Latino Patients Receiving FOLFOX

3.6.2. Early-Onset Hispanic/Latino Patients Without FOLFOX Exposure

3.6.3. Late-Onset Hispanic/Latino Patients Receiving FOLFOX

3.6.4. Late-Onset Hispanic/Latino Patients Without FOLFOX Treatment

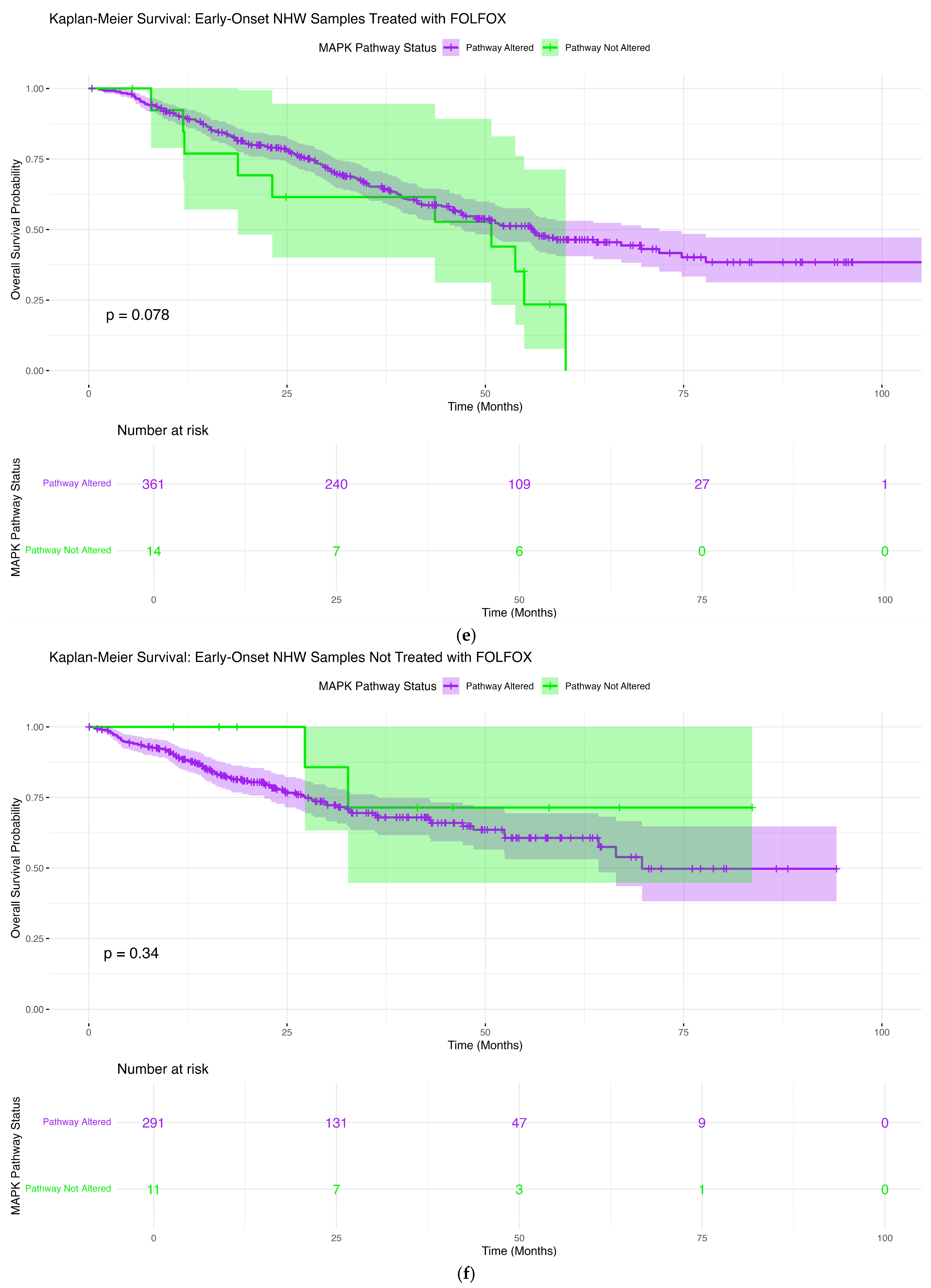

3.6.5. Early-Onset Non-Hispanic White Patients Treated with FOLFOX

3.6.6. Early-Onset NHW Patients Not Treated with FOLFOX

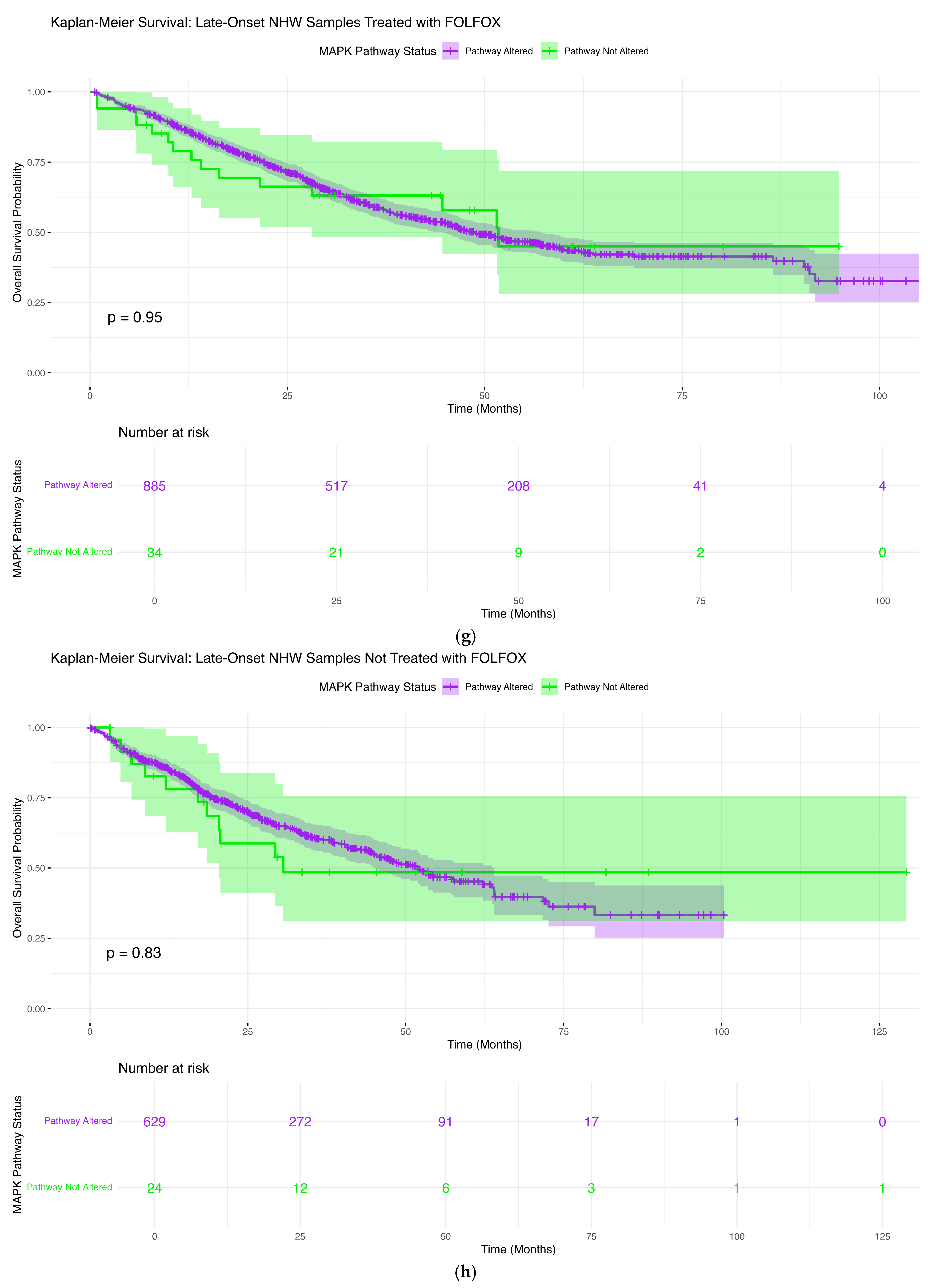

3.6.7. Late-Onset NHW Patients Treated with FOLFOX

3.6.8. Late-Onset NHW Patients Not Treated with FOLFOX

3.7. Conversational Artificial Intelligence

3.7.1. AI-Enabled Exploratory Cohort Stratification and Survival Assessment

3.7.2. AI-Assisted Comparison of MSI Stability in Early-Onset Hispanic/Latino CRC Stratified by Treatment Exposure

3.7.3. AI-Assisted Exploratory Comparison of AKT3 Mutation Frequency in Early-Onset NHW CRC by Treatment Exposure

3.7.4. AI-Guided Exploratory Comparison of PDGFRB Alterations in Early-Onset FOLFOX-Treated Patients Across Ancestry Groups

3.7.5. AI-Driven Identification of Mutation-Level Disparities Within MAPK-Altered Early-Onset Tumors Across Ancestry Groups

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Key Findings

4.2. Biological Implications of MAPK Pathway Alterations

4.3. Ancestry-Specific Genomic Patterns and Treatment Context

4.4. Implications for FOLFOX Response and Prognostic Stratification

4.5. AI-HOPE-MAPK as an Enabling Technology

4.6. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xie, Y.H.; Chen, Y.X.; Fang, J.Y. Comprehensive review of targeted therapy for colorectal cancer. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yan, L.; Shi, J.; Zhu, J. Cellular and molecular events in colorectal cancer: Biological mechanisms, cell death pathways, drug re-sistance and signalling network interactions. Discov. Oncol. 2024, 15, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Palma, S.; Zwenger, A.O.; Croce, M.V.; Abba, M.C.; Lacunza, E. From Molecular Biology to Clinical Trials: Toward Personalized Colo-rectal Cancer Therapy. Clin. Colorectal. Cancer 2016, 15, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dienstmann, R.; Tabernero, J. Spectrum of Gene Mutations in Colorectal Cancer: Implications for Treatment. Cancer J. 2016, 22, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, J.Y.; Richardson, B.C. The MAPK signalling pathways and colorectal cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2005, 6, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefani, C.; Miricescu, D.; Stanescu-Spinu, I.I.; Nica, R.I.; Greabu, M.; Totan, A.R.; Jinga, M. Growth Factors, PI3K/AKT/mTOR and MAPK Signaling Pathways in Colorectal Cancer Pathogenesis: Where Are We Now? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Appleyard, J.W.; Williams, C.J.M.; Manca, P.; Pietrantonio, F.; Seligmann, J.F. Targeting the MAP Kinase Pathway in Colorectal Cancer: A Journey in Personalized Medicine. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 31, 2565–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lièvre, A.; Blons, H.; Laurent-Puig, P. Oncogenic mutations as predictive factors in colorectal cancer. Oncogene 2010, 29, 3033–3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyamoto, Y.; Suyama, K.; Baba, H. Recent Advances in Targeting the EGFR Signaling Pathway for the Treatment of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mizukami, T.; Izawa, N.; Nakajima, T.E.; Sunakawa, Y. Targeting EGFR and RAS/RAF Signaling in the Treatment of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: From Current Treatment Strategies to Future Perspectives. Drugs 2019, 79, 633–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napolitano, S.; Martini, G.; Ciardiello, D.; Del Tufo, S.; Martinelli, E.; Troiani, T.; Ciardiello, F. Targeting the EGFR signalling pathway in metastatic colorectal cancer. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 9, 664–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saoudi González, N.; Ros, J.; Baraibar, I.; Salvà, F.; Rodríguez-Castells, M.; Alcaraz, A.; García, A.; Tabernero, J.; Élez, E. Cetuximab as a Key Partner in Personalized Targeted Therapy for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2024, 16, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Grossi, V.; Peserico, A.; Tezil, T.; Simone, C. p38α MAPK pathway: A key factor in colorectal cancer therapy and chemoresistance. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 9744–9758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Molavand, M.; Majidinia, M.; Yousefi, B. Critical Contribution of Various Signaling Pathways in the Development of Drug Re-sistance in Colorectal Cancer: An Update. IUBMB Life 2025, 77, e70074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeoh, Y.; Low, T.Y.; Abu, N.; Lee, P.Y. Regulation of signal transduction pathways in colorectal cancer: Implications for therapeutic resistance. PeerJ 2021, 9, e12338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, Y.; Deng, G.; Fu, Y.; Han, Y.; Guo, C.; Yin, L.; Cai, C.; Shen, H.; Wu, S.; Zeng, S. FOXC2 Promotes Oxaliplatin Resistance by Inducing Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition via MAPK/ERK Signaling in Colorectal Cancer. Onco. Targets Ther. 2020, 13, 1625–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chocry, M.; Leloup, L.; Kovacic, H. Reversion of resistance to oxaliplatin by inhibition of p38 MAPK in colorectal cancer cell lines: Involvement of the calpain/Nox1 pathway. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 103710–103730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Carracedo, A.; Ma, L.; Teruya-Feldstein, J.; Rojo, F.; Salmena, L.; Alimonti, A.; Egia, A.; Sasaki, A.T.; Thomas, G.; Kozma, S.C.; et al. Inhibition of mTORC1 leads to MAPK pathway activation through a PI3K-dependent feedback loop in human cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 2008, 118, 3065–3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Caruso, F.P.; D’Andrea, M.R.; Coppola, L.; Landriscina, M.; Condelli, V.; Cerulo, L.; Giordano, G.; Porras, A.; Pancione, M. Lymphocyte antigen 6G6D-mediated modulation through p38α MAPK and DNA methylation in colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2022, 22, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Monge, C.; Waldrup, B.; Carranza, F.G.; Velazquez-Villarreal, E. Ethnicity-Specific Molecular Alterations in MAPK and JAK/STAT Pathways in Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2025, 17, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, L.; Wang, X.; Sun, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xu, M.; Chi, P.; Lu, X.; Xu, Z. FBXW4 Acts as a Protector of FOLFOX-Based Chemotherapy in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Identified by Co-Expression Network Analysis. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chocry, M.; Leloup, L.; Parat, F.; Messé, M.; Pagano, A.; Kovacic, H. Gemcitabine: An Alternative Treatment for Oxaliplatin-Resistant Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 5894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Paillas, S.; Boissière, F.; Bibeau, F.; Denouel, A.; Mollevi, C.; Causse, A.; Denis, V.; Vezzio-Vié, N.; Marzi, L.; Cortijo, C.; et al. Targeting the p38 MAPK pathway inhibits irinotecan resistance in colon ade-nocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 1041–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jang, M.H.; Kim, S.; Hwang, D.Y.; Kim, W.Y.; Lim, S.D.; Kim, W.S.; Hwang, T.S.; Han, H.S. BRAF-Mutated Colorectal Cancer Exhibits Distinct Clinicopathological Features from Wild-Type BRAF-Expressing Cancer Independent of the Microsatellite Instability Status. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2017, 32, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bahar, M.E.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, D.R. Targeting the RAS/RAF/MAPK pathway for cancer therapy: From mechanism to clinical studies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bahrami, A.; Hesari, A.; Khazaei, M.; Hassanian, S.M.; Ferns, G.A.; Avan, A. The therapeutic potential of targeting the BRAF mutation in patients with colorectal cancer. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 233, 2162–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakayama, I.; Hirota, T.; Shinozaki, E. BRAF Mutation in Colorectal Cancers: From Prognostic Marker to Targetable Mutation. Cancers 2020, 12, 3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Napolitano, S.; Ciardiello, D.; Cioli, E.; Martinelli, E.; Troiani, T.; Giulia Zampino, M.; Fazio, N.; De Vita, F.; Ciardiello, F.; Martini, G. BRAFV600E mutant metastatic colorectal cancer: Current advances in personalized treatment and future perspectives. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2025, 134, 102905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebrun, H.; Turpin, A.; Zerbib, P. Therapeutic implications of B-RAF mutations in colorectal cancer. J. Visc. Surg. 2021, 158, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinelli, E.; Cremolini, C.; Mazard, T.; Vidal, J.; Virchow, I.; Tougeron, D.; Cuyle, P.J.; Chibaudel, B.; Kim, S.; Ghanem, I.; et al. Real-world first-line treatment of patients with BRAFV600E-mutant metastatic colorectal cancer: The CAPSTAN CRC study. ESMO Open 2022, 7, 100603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pfohl, U.; Loskutov, J.; Bashir, S.; Kühn, R.; Herter, P.; Templin, M.; Mamlouk, S.; Belanov, S.; Linnebacher, M.; Bürtin, F.; et al. A RAS-Independent Biomarker Panel to Reliably Predict Response to MEK Inhibition in Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pranteda, A.; Piastra, V.; Stramucci, L.; Fratantonio, D.; Bossi, G. The p38 MAPK Signaling Activation in Colorectal Cancer upon Therapeutic Treatments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Petrelli, F.; Antista, M.; Dottorini, L.; Russo, A.; Arru, M.; Invernizzi, R.; Manzoni, M.; Cremolini, C.; Zaniboni, A.; Garrone, O.; et al. First line therapy in stage IV BRAF mutated colorectal cancer. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Trunk, A.; Braithwaite, M.; Nevala-Plagemann, C.; Pappas, L.; Haaland, B.; Garrido-Laguna, I. Real-World Outcomes of Patients With BRAF-Mutated Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Treated in the United States. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 2022, 20, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Ren, J.; Liu, C.; Gai, Y.; Cheng, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, G. Comparative efficacy of cetuximab combined with FOLFOX or CAPEOX in first-line treatment of RAS/BRAF wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer: A multicenter case-control study. Anticancer Drugs 2025, 36, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yang, E.W.; Velazquez-Villarreal, E. AI-HOPE: An AI-driven conversational agent for enhanced clinical and genomic data inte-gration in precision medicine research. Bioinformatics 2025, 41, btaf359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yang, E.W.; Waldrup, B.; Velazquez-Villarreal, E. Artificial Intelligence for Precision Oncology: AI-HOPE-MAPK Uncovers Clini-cally Actionable MAPK Alterations in Colorectal Cancer. AI Precis. Oncol. 2025, 5, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, F.C.; Waldrup, B.; Carranza, F.G.; Manjarrez, S.; Velazquez-Villarreal, E. Artificial Intelligence-Guided Molecular Determinants of PI3K Pathway Alterations in Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer Among High-Risk Groups Receiving FOL-FOX. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, F.C.; Waldrup, B.; Carranza, F.G.; Manjarrez, S.; Velazquez-Villarreal, E. Artificial Intelligence-Enhanced Precision Medicine Reveals Prognostic Impact of TGF-Beta Pathway Alterations in FOLFOX-Treated Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer Among Dispro-portionately Affected Populations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Diaz, F.C.; Waldrup, B.; Carranza, F.G.; Manjarrez, S.; Velazquez-Villarreal, E. Precision Oncology Insights into WNT Pathway Al-terations in FOLFOX-Treated Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer in High-Risk Populations. Cancers 2025, 17, 2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mukhopadhyay, S.; Huang, H.Y.; Lin, Z.; Ranieri, M.; Li, S.; Sahu, S.; Liu, Y.; Ban, Y.; Guidry, K.; Hu, H.; et al. Genome-Wide CRISPR Screens Identify Multiple Synthetic Lethal Targets That Enhance KRASG12C Inhibitor Efficacy. Cancer Res. 2023, 83, 4095–4111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, F.; Liang, H.; Qin, X.; Mo, Y.; Chen, S.; Xie, J.; Hou, X.; Deng, J.; Hao, E.; et al. Hippo/YAP signaling pathway in colorectal cancer: Regulatory mechanisms and potential drug exploration. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1545952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Category | Variable | Hispanic/Latino (H/L) n = 266 | Non-Hispanic White (NHW) n = 2249 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Diagnosis & FOLFOX Exposure | EOCRC, FOLFOX-treated | 73 (27.4%) | 375 (16.7%) |

| EOCRC, not FOLFOX-treated | 52 (19.5%) | 302 (13.4%) | |

| LOCRC, FOLFOX-treated | 91 (34.2%) | 919 (40.9%) | |

| LOCRC, not FOLFOX-treated | 50 (18.8%) | 653 (29.0%) | |

| Tumor Site | Colon adenocarcinoma | 164 (61.7%) | 1328 (59.0%) |

| Rectal adenocarcinoma | 64 (24.1%) | 646 (28.7%) | |

| Colorectal adenocarcinoma (NOS) | 38 (14.3%) | 275 (12.2%) | |

| Sex | Male | 158 (59.4%) | 1267 (56.3%) |

| Female | 108 (40.6%) | 982 (43.7%) | |

| Tumor Sample Source | Primary tumor | 266 (100%) | 2249 (100%) |

| Clinical Stage at Diagnosis | Stage I–III | 156 (58.6%) | 1236 (55.0%) |

| Stage IV | 108 (40.6%) | 1005 (44.7%) | |

| Missing | 2 (0.8%) | 8 (0.4%) | |

| Microsatellite Status | MSS | 200 (75.2%) | 1940 (86.3%) |

| MSI-H | 21 (7.9%) | 209 (9.3%) | |

| Indeterminate | 10 (3.8%) | 57 (2.5%) | |

| Missing | 35 (13.2%) | 43 (1.9%) | |

| Ethnicity Annotation | Spanish/Hispanic NOS | 230 (86.5%) | — |

| Mexican/Chicano | 30 (11.3%) | — | |

| Other Hispanic categories * | 6 (2.3%) | — | |

| Non-Hispanic White | — | 2249 (100%) |

| (a) | ||||||

| Clinical Feature | Early-Onset Hispanic/Latino Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | Early-Onset Hispanic/Latino Not Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | p-Value | Late-Onset Hispanic/Latino Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | Late-Onset Hispanic/Latino Not Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | p-Value |

| Median Diagnosis Age (IQR) | 42 (36–47) | 40 (34–43) | 0.05411 | 59 (54–66) | 62 (56–70) | 0.04865 |

| Median Mutation Count | 7 (5–8) | 7 (5–20) | 0.09735 | 8 (6–9) [NA = 1] | 7 (5.25–9) | 0.6507 |

| Median TMB (IQR) | 6.3 (4.5–7.8) [NA = 15] | 5.5 (3.4–8.3) [NA = 2] | 0.1719 | 6.1 (4.9–7.8) [NA = 10] | 6.9 (5.6–9.0) [NA = 2] | 0.04389 |

| Median FGA | 0.18 (0.03–0.27) [NA = 6] | 0.19 (0.03–0.29) | 0.7661 | 0.15 (0.06–0.25) [NA = 7] | 0.21 (0.04–0.3) [NA = 2] | 0.5464 |

| FGFR2 Mutation | ||||||

| Present | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (7.7%) | 0.02793 | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.0%) | 0.3546 |

| Absent | 73 (100.0%) | 48 (92.3%) | 91 (100.0%) | 49 (98.0%) | ||

| NF1 Mutation | ||||||

| Present | 3 (4.1%) | 10 (19.2%) | 0.01437 | 2 (2.2%) | 2 (4.0%) | 0.615 |

| Absent | 70 (95.9%) | 42 (80.8%) | 89 (97.8%) | 48 (96.0%) | ||

| NTRK2 Mutation | ||||||

| Present | 1 (1.4%) | 2 (3.8%) | 0.5699 | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (6.0%) | 0.04286 |

| Absent | 72 (98.6%) | 50 (96.2%) | 91 (100.0%) | 47 (94.0%) | ||

| PDGFRB Mutation | ||||||

| Present | 4 (5.5%) | 3 (5.8%) | 1 | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (6.0%) | 0.04286 |

| Absent | 69 (94.5%) | 49 (94.2%) | 91 (100.0%) | 47 (94.0%) | ||

| RPS6KA4 Mutation | ||||||

| Present | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (9.6%) | 0.01108 | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (6.0%) | 0.6659 |

| Absent | 73 (100.0%) | 47 (90.4%) | 91 (100.0%) | 47 (94.0%) | ||

| (b) | ||||||

| Clinical Feature | Early-Onset NHW Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | Early-Onset NHW Not Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | p-Value | Late-Onset NHW Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | Late-Onset NHW Not Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | p-Value |

| Median Diagnosis Age (IQR) | 43 (37–48) | 44 (38–47) | 0.5646 | 63 (57–69) | 66 (57–74) | 4.146 × 10−7 |

| Median Mutation Count | 6 (5–8) [NA = 4] | 7 (5–9) [NA = 2] | 0.1258 | 7 (5–9) [NA = 10] | 8 (6–12) [NA = 3] | 1.22 × 10−5 |

| Median TMB (IQR) | 5.7 (4.1–6.9) | 5.7 (4.1–7.8) | 0.4214 | 6.1 (4.3–8.2) | 6.6 (4.9–10.4) | 0.0002854 |

| Median FGA | 0.14 (0.04–0.24) [NA = 4] | 0.15 (0.04–0.23) [NA = 2] | 0.5589 | 0.16 (0.06–0.28) [NA = 6] | 0.15 (0.05–0.27) [NA = 5] | 0.1929 |

| AKT3 Mutation | ||||||

| Present | 3 (0.8%) | 9 (3.0%) | 0.04069 | 9 (1.0%) | 12 (1.8%) | 0.2158 |

| Absent | 372 (99.2%) | 293 (97.0%) | 910 (99.0%) | 641 (98.2%) | ||

| CRKL Mutation | ||||||

| Present | 1 (0.3%) | 3 (1.0%) | 0.3291 | 1 (0.1%) | 8 (1.2%) | 0.004928 |

| Absent | 374 (99.7%) | 299 (99.0%) | 918 (99.9%) | 645 (98.8%) | ||

| DUSP4 Mutation | ||||||

| Present | 1 (0.3%) | 1 (0.3%) | 1 | 1 (0.1%) | 6 (0.9%) | 0.02292 |

| Absent | 374 (99.7%) | 301 (99.7%) | 918 (99.9%) | 647 (99.1%) | ||

| FGF4 Mutation | ||||||

| Present | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (1.7%) | 0.01734 | 1 (0.1%) | 4 (0.6%) | 0.167 |

| Absent | 375 (100.0%) | 297 (98.3%) | 918 (99.9%) | 649 (99.4%) | ||

| JUN Mutation | ||||||

| Present | 12 (3.2%) | 2 (0.7%) | 0.02726 | 13 (1.4%) | 21 (3.2%) | 0.02486 |

| Absent | 363 (96.8%) | 300 (99.3%) | 906 (98.6%) | 632 (96.8%) | ||

| MAPK1 Mutation | ||||||

| Present | 3 (0.8%) | 3 (1.0%) | 1 | 1 (0.1%) | 6 (0.9%) | 0.02292 |

| Absent | 372 (99.2%) | 299 (99.0%) | 918 (99.9%) | 647 (99.1%) | ||

| RRAS Mutation | ||||||

| Present | 4 (1.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.1326 | 2 (0.2%) | 8 (1.2%) | 0.02024 |

| Absent | 371 (98.9%) | 302 (100.0%) | 917 (99.8%) | 645 (98.8%) | ||

| RRAS2 Mutation | ||||||

| Present | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (1.3%) | 0.03916 | 5 (0.5%) | 3 (0.5%) | 1 |

| Absent | 375 (100.0%) | 298 (98.7%) | 914 (99.5%) | 650 (99.5%) | ||

| SOS1 Mutation | ||||||

| Present | 7 (1.9%) | 11 (3.6%) | 0.2351 | 8 (0.9%) | 15 (2.3%) | 0.03501 |

| Absent | 368 (98.1%) | 291 (96.4%) | 911 (99.1%) | 638 (97.7%) | ||

| (c) | ||||||

| Clinical Feature | Early-Onset Hispanic/Latino Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | Early-Onset NHW Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | p-Value | Early-Onset Hispanic/Latino Not Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | Early-Onset NHW Not Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | p-Value |

| Median Diagnosis Age (IQR) | 42 (36–47) | 43 (37–48) | 0.08467 | 40 (34–43) | 44 (38–47) | 0.0006016 |

| Median Mutation Count | 7 (5–8) | 6 (5–8) [NA = 4] | 0.942 | 7 (5–20) | 7 (5–9) [NA = 2] | 0.2601 |

| Median TMB (IQR) | 6.3 (4.5–7.8) [NA = 15] | 5.7 (4.1–6.9) | 0.05806 | 5.5 (3.4–8.3) [NA = 2] | 5.7 (4.1–7.8) | 0.5732 |

| Median FGA | 0.18 (0.03–0.27) [NA = 6] | 0.14 (0.04–0.24) [NA = 4] | 0.5556 | 0.19 (0.03–0.29) | 0.15 (0.04–0.23) [NA = 2] | 0.3612 |

| MAPK3 Mutation | ||||||

| Present | 1 (1.4%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0.2996 | 3 (5.8%) | 3 (1.0%) | 0.04335 |

| Absent | 72 (98.6%) | 374 (99.7%) | 49 (94.2%) | 299 (99.0%) | ||

| NF1 Mutation | ||||||

| Present | 3 (4.1%) | 17 (4.5%) | 1 | 10 (19.2%) | 18 (6.0%) | 0.002728 |

| Absent | 70 (95.9%) | 358 (95.5%) | 42 (80.8%) | 284 (94.0%) | ||

| PDGFRB Mutation | ||||||

| Present | 4 (5.5%) | 3 (0.8%) | 0.01547 | 3 (5.8%) | 7 (2.3%) | 0.1693 |

| Absent | 69 (94.5%) | 372 (99.2%) | 49 (94.2%) | 295 (97.7%) | ||

| RPS6KA4 Mutation | ||||||

| Present | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (1.3%) | 1 | 5 (9.6%) | 8 (2.6%) | 0.03866 |

| Absent | 73 (100.0%) | 370 (98.7%) | 47 (90.4%) | 294 (97.4%) | ||

| (a) | ||||||

| Pathway Alterations | Early-Onset Hispanic/Latino Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | Early-Onset Hispanic/Latino Not Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | p-Value | Late-Onset Hispanic/Latino Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | Late-Onset Hispanic/Latino Not Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | p-Value |

| MAPK Alterations Present | 70 (95.9%) | 52 (100.0%) | 0.2653 | 89 (97.8%) | 50 (100.0%) | 0.539 |

| MAPK Alterations Absent | 3 (4.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (2.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| (b) | ||||||

| Pathway Alterations | Early-Onset NHW Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | Early-Onset NHW Not Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | p-Value | Late-Onset NHW Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | Late-Onset NHW Not Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | p-Value |

| MAPK Alterations Present | 361 (96.3%) | 291 (96.4%) | 1 | 885 (96.3%) | 629 (96.3%) | 1 |

| MAPK Alterations Absent | 14 (3.7%) | 11 (3.6%) | 34 (3.7%) | 24 (3.7%) | ||

| (c) | ||||||

| Pathway Alterations | Early-Onset Hispanic/Latino Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | Early-Onset NHW Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | p-Value | Early-Onset Hispanic/Latino Not Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | Early-Onset NHW Not Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | p-Value |

| MAPK Alterations Present | 70 (95.9%) | 361 (96.3%) | 0.7469 | 52 (100.0%) | 291 (96.4%) | 0.379 |

| MAPK Alterations Absent | 3 (4.1%) | 14 (3.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 11 (3.6%) | ||

| (d) | ||||||

| Pathway Alterations | Late-Onset Hispanic/Latino Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | Late-Onset NHW Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | p-Value | Late-Onset Hispanic/Latino Not Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | Late-Onset NHW Not Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | p-Value |

| MAPK Alterations Present | 89 (97.8%) | 885 (96.3%) | 0.7646 | 50 (100.0%) | 629 (96.3%) | 0.4049 |

| MAPK Alterations Absent | 2 (2.2%) | 34 (3.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 24 (3.7%) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Diaz, F.C.; Waldrup, B.; Carranza, F.G.; Manjarrez, S.; Velazquez-Villarreal, E. Conversational AI-Enabled Precision Oncology Reveals Context-Dependent MAPK Pathway Alterations in Hispanic/Latino and Non-Hispanic White Colorectal Cancer Stratified by Age and FOLFOX Exposure. Cancers 2026, 18, 293. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020293

Diaz FC, Waldrup B, Carranza FG, Manjarrez S, Velazquez-Villarreal E. Conversational AI-Enabled Precision Oncology Reveals Context-Dependent MAPK Pathway Alterations in Hispanic/Latino and Non-Hispanic White Colorectal Cancer Stratified by Age and FOLFOX Exposure. Cancers. 2026; 18(2):293. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020293

Chicago/Turabian StyleDiaz, Fernando C., Brigette Waldrup, Francisco G. Carranza, Sophia Manjarrez, and Enrique Velazquez-Villarreal. 2026. "Conversational AI-Enabled Precision Oncology Reveals Context-Dependent MAPK Pathway Alterations in Hispanic/Latino and Non-Hispanic White Colorectal Cancer Stratified by Age and FOLFOX Exposure" Cancers 18, no. 2: 293. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020293

APA StyleDiaz, F. C., Waldrup, B., Carranza, F. G., Manjarrez, S., & Velazquez-Villarreal, E. (2026). Conversational AI-Enabled Precision Oncology Reveals Context-Dependent MAPK Pathway Alterations in Hispanic/Latino and Non-Hispanic White Colorectal Cancer Stratified by Age and FOLFOX Exposure. Cancers, 18(2), 293. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020293