The Impact of Endpoint Definitions on Predictors of Progression in Active Surveillance for Early Prostate Cancer

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cohort Description and Outcomes Reported

2.2. Variables Tested for Active Surveillance Progression Endpoints

2.3. Outcome Measures

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Cohort Demographics

3.2. Value of Biopsy and MRI Characteristics in Predicting Progression to (CPG3 Disease

3.3. Value of Biopsy and MRI Characteristics in Predicting Any Pathological/Radiological Stage Progression

3.4. Clinicopathological Characteristics Used to Predict Time-to-Progression

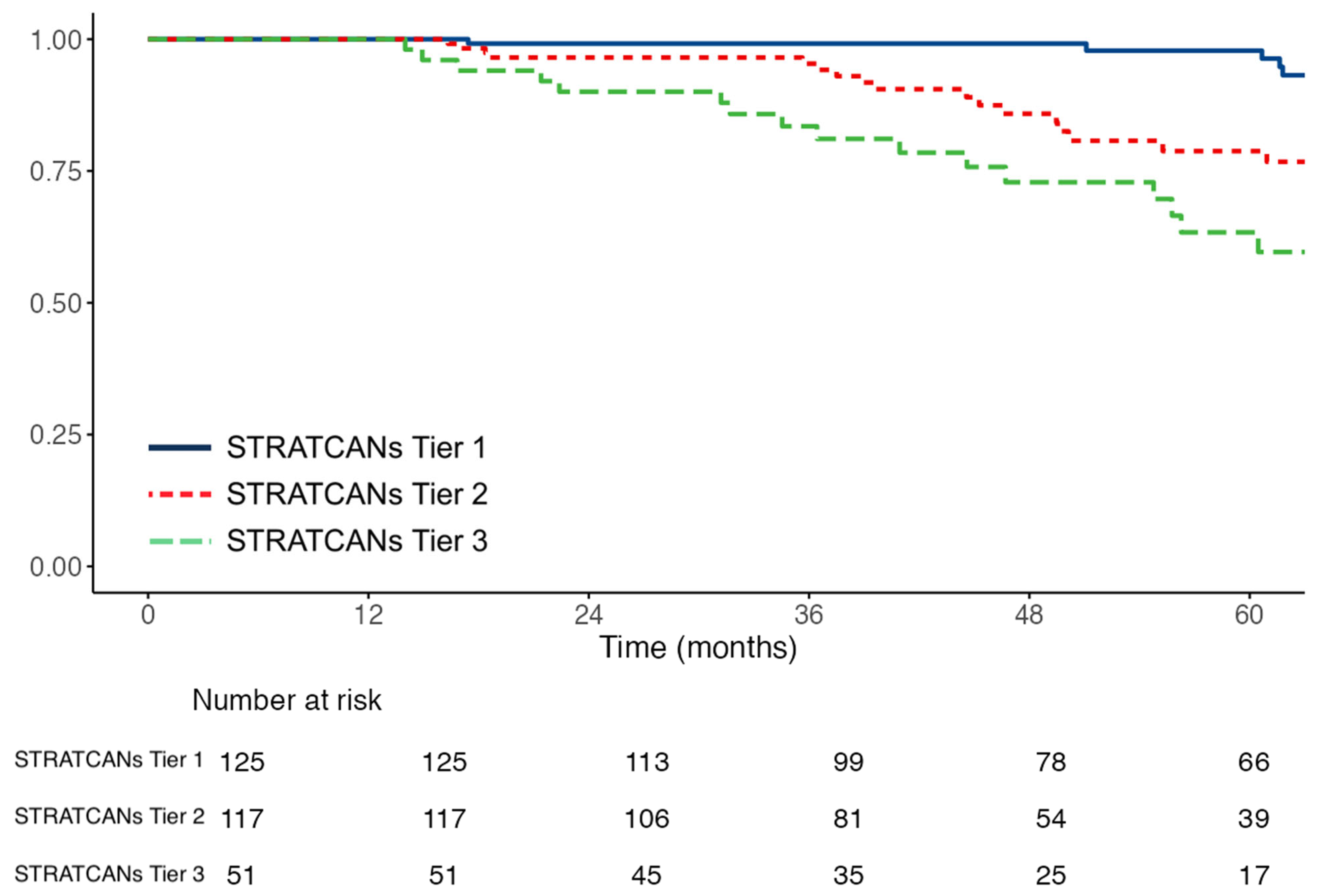

3.5. Progression Endpoint Definition and the Predictive Value of Different AS Variables

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AS | Active surveillance |

| PCa | Prostate cancer |

| CPG | Cambridge Prognostic Group |

| STRATCANs | STRATified CANcer Surveillance |

| PSA | Prostate-specific antigen |

| PSAd | Prostate-specific antigen density |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| PI-RADS | Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System |

| GG | Grade group |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| TTP | Time to progression |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| BCR | Biochemical recurrence |

| NICE | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence |

| EAU | European Association of Urology |

References

- Eastham, J.A.; Auffenberg, G.B.; Barocas, D.A.; Chou, R.; Crispino, T.; Davis, J.W.; Eggener, S.; Horwitz, E.M.; Kane, C.J.; Kirkby, E.; et al. Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer: AUA/ASTRO Guideline, Part I: Introduction, Risk Assessment, Staging, and Risk-Based Manage-ment. J. Urol. 2022, 208, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornford, P.; van den Bergh, R.C.N.; Briers, E.; Van den Broeck, T.; Brunckhorst, O.; Darraugh, J.; Eberli, D.; De Meerleer, G.; De Santis, M.; Farolfi, A.; et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-ISUP-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer-2024 Update. Part I: Screening, Diagnosis, and Local Treatment with Curative Intent. Eur. Urol. 2024, 86, 148–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.C.; Rumble, R.B.; Loblaw, D.A.; Finelli, A.; Ehdaie, B.; Cooperberg, M.R.; Morgan, S.C.; Tyldesley, S.; Haluschak, J.J.; Tan, W.; et al. Active Surveillance for the Management of Localized Prostate Cancer (Cancer Care Ontario Guideline): American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Endorsement. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 2182–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotz, L.; Vesprini, D.; Sethukavalan, P.; Jethava, V.; Zhang, L.; Jain, S.; Yamamoto, T.; Mamedov, A.; Loblaw, A. Long-term follow-up of a large active surveillance cohort of patients with prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosoian, J.J.; Mamawala, M.; Epstein, J.I.; Landis, P.; Macura, K.J.; Simopoulos, D.N.; Carter, H.B.; Gorin, M.A. Active Surveillance of Grade Group 1 Prostate Cancer: Long-term Outcomes from a Large Prospective Cohort. Eur. Urol. 2020, 77, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlsson, S.; Benfante, N.; Alvim, R.; Sjoberg, D.D.; Vickers, A.; Reuter, V.E.; Fine, S.W.; Vargas, H.A.; Wiseman, M.; Mamoor, M.; et al. Long-Term Outcomes of Active Surveillance for Prostate Cancer: The Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Experience. J. Urol. 2020, 203, 1122–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godtman, R.A.; Holmberg, E.; Khatami, A.; Pihl, C.G.; Stranne, J.; Hugosson, J. Long-term Results of Active Surveillance in the Göteborg Randomized, Population-based Prostate Cancer Screening Trial. Eur. Urol. 2016, 70, 760–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, D.M.; Kim, J.K.; Lee, S.; Hong, S.K.; Byun, S.S.; Lee, S.E. Prediction of pathologic upgrading in Gleason score 3+4 prostate cancer: Who is a candidate for active surveillance? Investig. Clin. Urol. 2020, 61, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschheidgen, M.; Schimmoller, L.; Arsov, C.; Ziayee, F.; Morawitz, J.; Valentin, B.; Radke, K.L.; Giessing, M.; Esposito, I.; Albers, P.; et al. MRI grading for the prediction of prostate cancer aggressiveness. Eur. Radiol. 2022, 32, 2351–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, J.I.; Feng, Z.; Trock, B.J.; Pierorazio, P.M. Upgrading and downgrading of prostate cancer from biopsy to radical prostatectomy: Incidence and predictive factors using the modified Gleason grading system and factoring in tertiary grades. Eur. Urol. 2012, 61, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.K.; Han, B.K.; Lee, S.T.; Kim, S.S.; Min, K.E.; Jeong, S.J.; Jeong, H.; Byun, S.S.; Lee, H.J.; Choe, G.; et al. Prediction of Gleason score upgrading in low-risk prostate cancers diagnosed via multi (> or = 12)-core prostate biopsy. World J. Urol. 2009, 27, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammia, R.S.; Hoeh, B.; Hohenhorst, L.; Sorce, G.; Chierigo, F.; Panunzio, A.; Tian, Z.; Saad, F.; Leonardo, C.; Briganti, A.; et al. Adverse upgrading and/or upstaging in contemporary low-risk prostate cancer patients. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2022, 54, 2521–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verep, S.; Erdem, S.; Ozluk, Y.; Kilicaslan, I.; Sanli, O.; Ozcan, F. The pathological upgrading after radical prostatectomy in low-risk prostate cancer patients who are eligible for active surveillance: How safe is it to depend on bioptic pathology? Prostate 2019, 79, 1523–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newcomb, L.F.; Thompson, I.M.; Boyer, H.D.; Brooks, J.D.; Carroll, P.R.; Cooperberg, M.R.; Dash, A.; Ellis, W.J.; Fazli, L.; Feng, Z.; et al. Outcomes of Active Surveillance for Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer in the Prospective, Multi-Institutional Canary PASS Cohort. J. Urol. 2016, 195, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seisen, T.; Roudot-Thoraval, F.; Bosset, P.O.; Beaugerie, A.; Allory, Y.; Vordos, D.; Abbou, C.-C.; De La Taille, A.; Salomon, L. Predicting the risk of harboring high-grade disease for patients diagnosed with prostate cancer scored as Gleason ≤ 6 on biopsy cores. World J. Urol. 2015, 33, 787–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanapragasam, V.J.; Barrett, T.; Thankapannair, V.; Thurtle, D.; Rubio-Briones, J.; Dominguez-Escrig, J.; Bratt, O.; Statin, P.; Muir, K.; Lophatananon, A. Using prognosis to guide inclusion criteria, define standardised endpoints and stratify follow-up in active surveillance for prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2019, 124, 758–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Light, A.; Lophatananon, A.; Keates, A.; Thankappannair, V.; Barrett, T.; Dominguez-Escrig, J.; Rubio-Briones, J.; Benheddi, T.; Olivier, J.; Villers, A.; et al. Development and External Validation of the STRATified CANcer Surveillance (STRATCANS) Multivariable Model for Predicting Progression in Men with Newly Diagnosed Prostate Cancer Starting Active Surveillance. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 12, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnanapragasam, V.J.; Keates, A.; Lophatananon, A.; Thankapannair, V. The 5-year results of the Stratified Cancer Active Surveillance programme for men with prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2025, 135, 851–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thankapannair, V.; Keates, A.; Barrett, T.; Gnanapragasam, V.J. Prospective Implementation and Early Outcomes of a Risk-stratified Prostate Cancer Active Surveillance Follow-up Protocol. Eur. Urol. Open Sci. 2023, 49, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Prostate Cancer: Diagnosis and Management 2021. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng131 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Englman, C.; Adebusoye, B.; Maffei, D.; Stavrinides, V.; Bridge, J.; Kirkham, A.; Allen, C.; Dickinson, L.; Pendse, D.; Punwani, S.; et al. Magnetic Resonance Imaging-led Risk-adapted Active Surveillance for Prostate Cancer: Updated Results from a Large Cohort Study. Eur. Urol. 2025, 88, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sushentsev, N.; Li, I.G.; Xu, G.; Warren, A.Y.; Hsu, C.Y.; Baxter, M.; Panchal, D.; Kastner, C.; Fernando, S.; Pazukhina, E.; et al. Predicting Active Surveillance Failure for Patients with Prostate Cancer in the Magnetic Resonance Imaging Era: A Multicentre Transatlantic Cohort Study. Eur Urol Oncol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinsella, N.; Helleman, J.; Bruinsma, S.; Carlsson, S.; Cahill, D.; Brown, C.; Van Hemelrijck, M. Active surveillance for prostate cancer: A systematic review of contemporary worldwide practices. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2018, 7, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyrottes, A.; Baboudjian, M.; Diamand, R.; Ducrot, Q.; Vitard, C.; Baudewyns, A.; Windisch, O.; Anract, J.; Dariane, C.; Tricard, T.; et al. Reliability of Serial Prostate Magnetic Resonance Imaging to Detect Prostate Cancer Progression During Active Surveillance: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Eur. Urol. 2021, 80, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.E.; Hayen, A.; Landau, A.; Haynes, A.M.; Kalapara, A.; Ischia, J.; Matthews, J.; Frydenberg, M.; Stricker, P.D. Medium-term oncological outcomes for extended vs saturation biopsy and transrectal vs transperineal biopsy in active surveillance for prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2015, 115, 884–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welty, C.J.; Cowan, J.E.; Nguyen, H.; Shinohara, K.; Perez, N.; Greene, K.L.; Chan, J.M.; Meng, M.V.; Simko, J.P.; Cooperberg, M.R.; et al. Extended followup and risk factors for disease reclassification in a large active surveillance cohort for localized prostate cancer. J. Urol. 2015, 193, 807–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvadurai, E.D.; Singhera, M.; Thomas, K.; Mohammed, K.; Woode-Amissah, R.; Horwich, A.; Huddart, R.A.; Dearnaley, D.P.; Parker, C.C. Medium-term outcomes of active surveillance for localised prostate cancer. Eur. Urol. 2013, 64, 981–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shee, K.; Nie, J.; Cowan, J.E.; Wang, L.; Washington, S.L.; Shinohara, K.; Nguyen, H.G.; Cooperberg, M.R.; Carroll, P.R. Determining Long-term Prostate Cancer Outcomes for Active Surveillance Patients Without Early Disease Progression: Implications for Slowing or Stopping Surveillance. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2025, 8, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesnut, G.T.; Vertosick, E.A.; Benfante, N.; Sjoberg, D.D.; Fainberg, J.; Lee, T.; Eastham, J.; Laudone, V.; Scardino, P.; Touijer, K.; et al. Role of Changes in Magnetic Resonance Imaging or Clinical Stage in Evaluation of Disease Progression for Men with Prostate Cancer on Active Surveillance. Eur. Urol. 2020, 77, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giganti, F.; Stabile, A.; Stavrinides, V.; Osinibi, E.; Retter, A.; Orczyk, C.; Panebianco, V.; Trock, B.J.; Freeman, A.; Haider, A.; et al. Natural history of prostate cancer on active surveillance: Stratification by MRI using the PRECISE recommendations in a UK cohort. Eur. Radiol. 2021, 31, 1644–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peyrottes, A.; Baboudjian, M.; Diamand, R.; Ducrot, Q.; Vitard, C.; Baudewyns, A.; Windisch, O.; Anract, J.; Dariane, C.; Tricard, T.; et al. Are Patients with Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System 5 Lesions Eligible for Active Surveillance? A Multicentric European Study. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2025, 8, 1260–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahdoot, M.; Wilbur, A.R.; Reese, S.E.; Lebastchi, A.H.; Mehralivand, S.; Gomella, P.T.; Bloom, J.; Gurram, S.; Siddiqui, M.; Pinsky, P.; et al. MRI-Targeted, Systematic, and Combined Biopsy for Prostate Cancer Diagnosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 917–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokhorst, L.P.; Valdagni, R.; Rannikko, A.; Kakehi, Y.; Pickles, T.; Bangma, C.H.; Roobol, M.J.; PRIAS study group. A Decade of Active Surveillance in the PRIAS Study: An Update and Evaluation of the Criteria Used to Recommend a Switch to Active Treatment. Eur. Urol. 2016, 70, 954–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmstedt, E.; Mansson, M.; Hugosson, J.; Arnsrud Godtman, R. Active Surveillance for Screen-detected Low- and Intermediate-risk Prostate Cancer: Extended Follow-up up to 25 Years in the GOTEBORG-1 Trial. Eur. Urol. 2025, 88, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusev, A.; Rumpf, F.; Zlatev, D.; Twum-Ampofo, J.; Gore, J.L.; Dahl, D.; Wszolek, M.F.; Efstathiou, J.A.; Lee, R.J.; Blute, M.L.; et al. PSA density as a dynamic prognostic marker of biopsy grade progression during active surveillance. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2025, 43, 709.e9–709.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, A.M.; Wang, M.; Zamani, A.; Meah, S.; Daignault-Newton, S.; Labardee, C.; Dybas, N.; Clapper, J.; Lane, B.R.; Borza, T.; et al. Application of the STRATCANS Criteria to the MUSIC Prostate Cancer Active Surveillance Cohort: A Step Towards Risk-Stratified Active Surveillance. Cancers 2025, 17, 3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Cancer Control Programme. HSE National Clinical Guideline: Active Surveillance for Patients with Prostate Cancer. 2025. Available online: https://www2.healthservice.hse.ie/files/495/ (accessed on 13 January 2026).

- Willemse, P.M.; Davis, N.F.; Grivas, N.; Zattoni, F.; Lardas, M.; Briers, E.; Cumberbatch, M.G.; De Santis, M.; Dell’Oglio, P.; Donaldson, J.F.; et al. Systematic Review of Active Surveillance for Clinically Localised Prostate Cancer to Develop Recommendations Regarding Inclusion of Intermediate-risk Disease, Biopsy Characteristics at Inclusion and Monitoring, and Surveillance Repeat Biopsy Strategy. Eur. Urol. 2022, 81, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (years) (n = 296) | |

| Mean | 66 |

| Median (IQR) | 66 (61–71) |

| PSA (ng/mL) (n = 296) | |

| Mean | 6.80 |

| Median (IQR) | 6.13 (4.47–8.08) |

| PSAd (ng/mL/mL) (n = 293) | |

| Mean | 0.14 |

| Median (IQR) | 0.12 (0.09–0.17) |

| MRI Likert score (n = 279) | n (%) |

| Likert 1–2 | 73 (26.2) |

| Likert 3–5 | 206 (73.8) |

| Cambridge Prognostic Group (CPG) (n = 296) | n (%) |

| CPG 1 | 180 (60.8) |

| CPG 2 | 116 (39.2) |

| Grade Group (n = 296) | n (%) |

| GG1 | 78 (26.4) |

| GG2 | 218 (73.6) |

| STRATCANS tier (n = 296) | n (%) |

| 1 | 127 (42.9) |

| 2 | 118 (39.9) |

| 3 | 51 (17.2) |

| Years on AS whole cohort (n = 296) | |

| Mean | 4.53 |

| Median (IQR) | 4.11 (2.89–6.53) |

| Years on AS men still on surveillance (n = 150) | |

| Mean | 5.89 |

| Median (IQR) | 5.23 (3.29–8.40) |

| Progression event by definition | n (%) |

| To ≥CPG3 | 46 (15.5) |

| Any objective pathological/radiological progression | 54 (18.2) |

| Definition 3 | 84 (28.4) |

| Definition 4 | 10 (3.4) |

| Variables at Baseline | Progression to ≥CPG 3 Disease Odds Ratio (95% CI) p-Value | Any Pathological/Stage Progression Odds Ratio (95% CI) p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (n = 296) | 1.02 (0.98–1.07) p = 0.36 | 1.00 (0.96–1.03) p = 0.80 |

| PSA (n = 296) | 1.08 (0.99–1.19) p = 0.07 | 0.98 (0.90–1.06) p = 0.63 |

| PSA density (PSAd) * (n = 293) | 3.64 (1.82–7.28) p < 0.001 | 2.36 (1.36–4.09) p = 0.004 |

| Grade Group (n = 296) | 1.82 (0.93–3.53) p = 0.08 | 1.07 (0.59–1.95) p = 0.82 |

| Cambridge Prognostic Group (n = 296) | 2.33 (1.23–4.44) p = 0.009 | 1.12 (0.65–1.92) p = 0.68 |

| Core positivity (%) (n = 286) | 4.71 (0.85–26.05) p = 0.08 | 9.88 (2.20–44.45) p = 0.003 |

| Percentage cancer involvement (%) (n = 146) | 1.02 (1.00–1.05) p = 0.08 | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) p = 0.09 |

| Cancer core length (mm) (n = 226) | 1.08 (0.98–1.19) p = 0.13 | 1.07 (0.98–1.16) p = 0.12 |

| MRI Likert score (n = 279) | 1.34 (1.04–1.72) p = 0.02 | 1.28 (1.04–1.56) p = 0.01 |

| MRI lesion size (mm2) (n = 138) | 1.00 (1.00–1.01) p = 0.56 | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) p = 0.69 |

| MRI lesion laterality (n = 289) | 1.00 (0.78–1.30) p = 0.97 | 1.03 (0.83–1.28) p = 0.80 |

| MRI lesion location (n = 215) | 0.92 (0.82–1.02) p = 0.12 | 0.95 (0.87–1.04) p = 0.28 |

| Variable at Baseline | Progression to ≥CPG 3 Disease Hazard Ratio (95% CI) p-Value | Any Pathological/Radiological Stage Progression Hazard Ratio (95% CI) p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| PSA density (PSAd) * (n = 293) | 1.99 (1.41–2.81) p < 0.001 | 1.83 (1.34–2.48) p < 0.001 |

| Core positivity (%) (n = 286) | - | 1.03 (1.02–1.04) p < 0.001 |

| Cambridge Prognostic Group (n = 296) | 2.01 (1.28–3.15) p = 0.003 | - |

| MRI Likert score (n = 279) | 2.54 (1.17–5.49) p = 0.018 | 2.02 (1.03–3.95) p = 0.04 |

| STRATCANs tier (n = 296) | ||

| STRATCANs Tier 2 vs. Tier 1 | 2.51 (1.17–5.41) p = 0.019 | 1.52 (0.83–2.77) p = 0.17 |

| STRATCANs Tier 3 vs. Tier 1 STRATCANs Tier | 4.99 (2.28–10.91) p < 0.001 | 1.63 (0.78–3.40) p = 0.20 |

| STRATCANs Tier 3 vs. Tier 2 | 1.99 (1.03–3.83) p = 0.04 | 1.09 (0.53–2.24) p = 0.81 |

| Variable at Baseline | Progression to ≥CPG 3 Disease Odds Ratio (95% CI) p-Value | Any Pathological/Stage Progression Odds Ratio (95% CI) p-Value | Definition 3 Odds Ratio (95% CI) p-Value | Definition 4 Odds Ratio (95% CI) p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (n = 296) | 1.02 (0.98–1.07) p = 0.36 | 1.00 (0.96–1.03) p = 0.80 | 1.00 (0.97–1.04) p = 0.94 | 1.06 (0.96–1.17) p = 0.26 |

| PSA (n = 296) | 1.08 (0.99–1.19) p = 0.07 | 0.98 (0.90–1.06) p = 0.63 | 1.02 (0.94–1.09) p = 0.70 | 1.05 (0.89–1.25) p = 0.56 |

| PSA density (PSAd) * (n = 293) | 3.64 (1.82–7.28) p < 0.001 | 2.36 (1.36–4.09) p = 0.004 | 3.04 (1.75–5.28) p = 0.002 | 2.47 (0.68–8.95) p = 0.17 |

| Grade Group (n = 296) | 1.82 (0.93–3.53) p = 0.08 | 1.07 (0.59–1.95) p = 0.82 | 1.66 (0.95–2.89) p = 0.07 | 1.22 (0.31–4.83) p = 0.78 |

| Cambridge Prognostic Group (n = 296) | 2.33 (1.23–4.44) p = 0.009 | 1.12 (0.65–1.92) p = 0.68 | 1.48 (0.88–2.48) p = 0.14 | 1.56 (0.44–5.51) p = 0.49 |

| Core positivity (%) (n = 286) | 4.71 (0.85–26.05) p = 0.08 | 9.88 (2.20–44.45) p = 0.003 | 9.72 (2.25–42.10) p = 0.002 | 0.10 (0.00–12.50) p = 0.35 |

| Percentage cancer involvement (%) (n = 146) | 1.02 (1.00–1.05) p = 0.08 | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) p = 0.09 | 1.02 (0.99–1.04) p = 0.14 | 0.97 (0.88–1.07) p = 0.56 |

| Cancer core length (mm) (n = 226) | 1.08 (0.98–1.19) p = 0.13 | 1.07 (0.98–1.16) p = 0.12 | 1.13 (1.04–1.22) p = 0.005 | 0.87 (0.66–1.14) p = 0.31 |

| MRI Likert score (n = 279) | 1.34 (1.04–1.72) p = 0.02 | 1.28 (1.04–1.56) p = 0.01 | 1.36 (1.12–1.65) p = 0.003 | 0.94 (0.60–1.48) p = 0.79 |

| MRI lesion size (mm2) (n = 138) | 1.00 (1.00–1.01) p = 0.56 | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) p = 0.69 | 1.00 (1.00–1.01) p = 0.11 | 1.00 (0.98–1.01) p = 0.83 |

| MRI lesion laterality (n = 289) | 1.00 (0.78–1.30) p = 0.97 | 1.03 (0.83–1.28) p = 0.80 | 0.96 (0.78–1.19) p = 0.68 | 1.40 (0.83–2.35) p = 0.20 |

| MRI lesion location (n = 215) | 0.92 (0.82–1.02) p = 0.12 | 0.95 (0.87–1.04) p = 0.28 | 0.94 (0.86–1.02) p = 0.14 | 1.10 (0.88–1.36) p = 0.40 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sandhu, K.; Lophatananon, A.; Gnanapragasam, V.J. The Impact of Endpoint Definitions on Predictors of Progression in Active Surveillance for Early Prostate Cancer. Cancers 2026, 18, 292. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020292

Sandhu K, Lophatananon A, Gnanapragasam VJ. The Impact of Endpoint Definitions on Predictors of Progression in Active Surveillance for Early Prostate Cancer. Cancers. 2026; 18(2):292. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020292

Chicago/Turabian StyleSandhu, Kieran, Artitaya Lophatananon, and Vincent J. Gnanapragasam. 2026. "The Impact of Endpoint Definitions on Predictors of Progression in Active Surveillance for Early Prostate Cancer" Cancers 18, no. 2: 292. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020292

APA StyleSandhu, K., Lophatananon, A., & Gnanapragasam, V. J. (2026). The Impact of Endpoint Definitions on Predictors of Progression in Active Surveillance for Early Prostate Cancer. Cancers, 18(2), 292. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020292