Identification and Characterisation of Canine Osteosarcoma Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Specimen Preparation and Ethics

2.2. Immunohistochemistry and Microscopy

2.3. H-Scoring, Statistical and Bioinformatic Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Protein Levels of Four Genes Highly Expressed in Canine Osteosarcomas

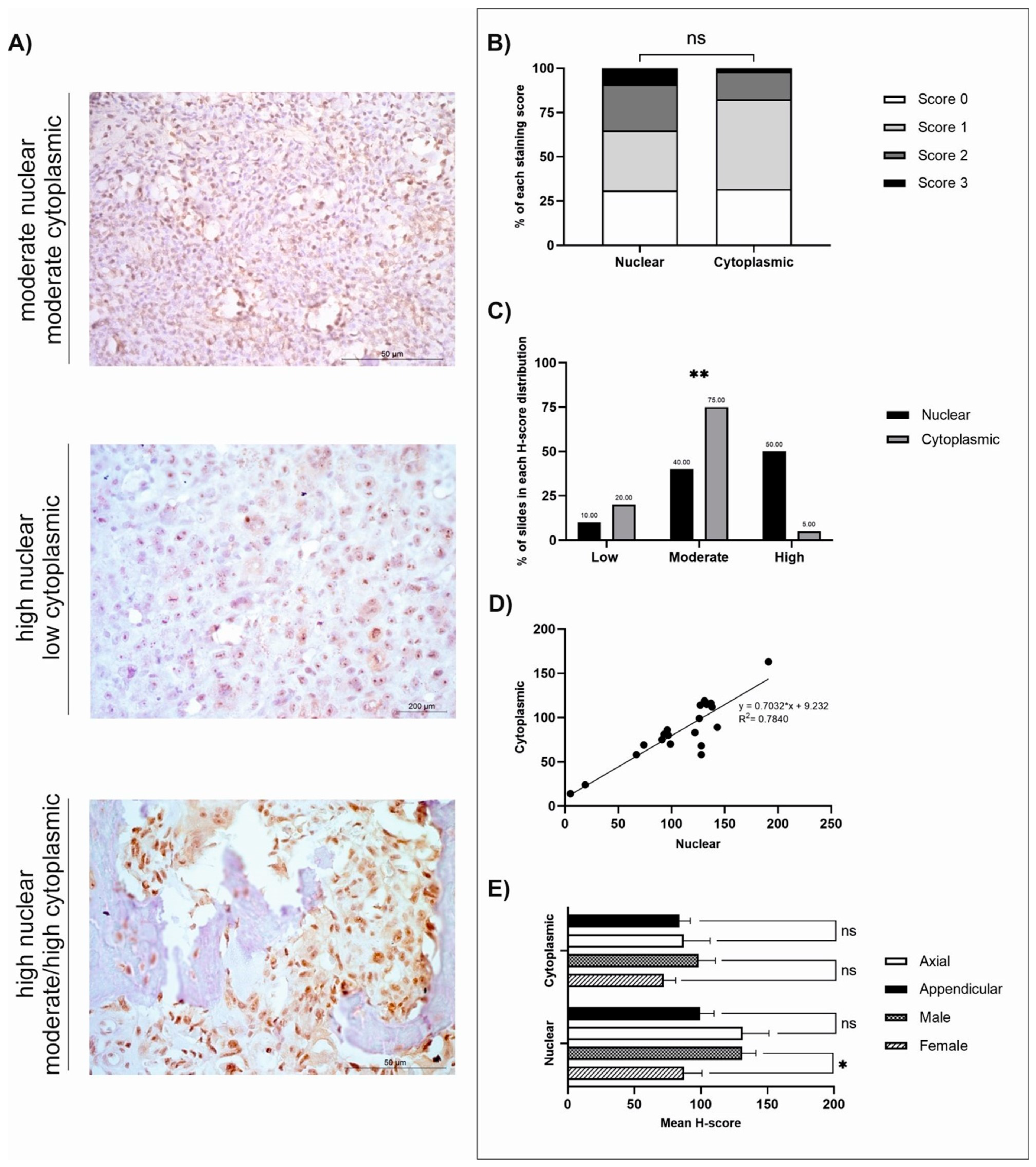

3.2. GPR64

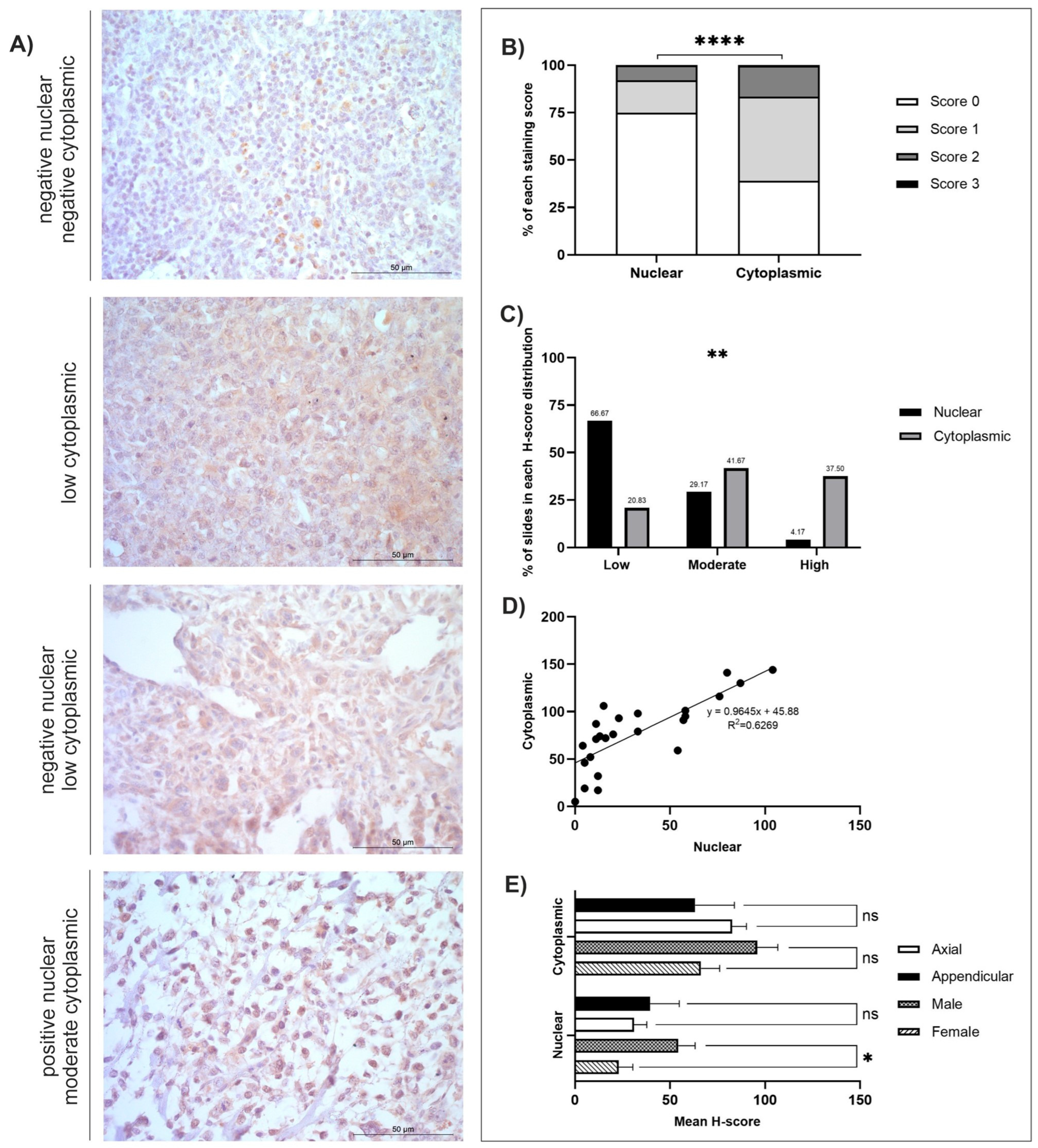

3.3. TOX3

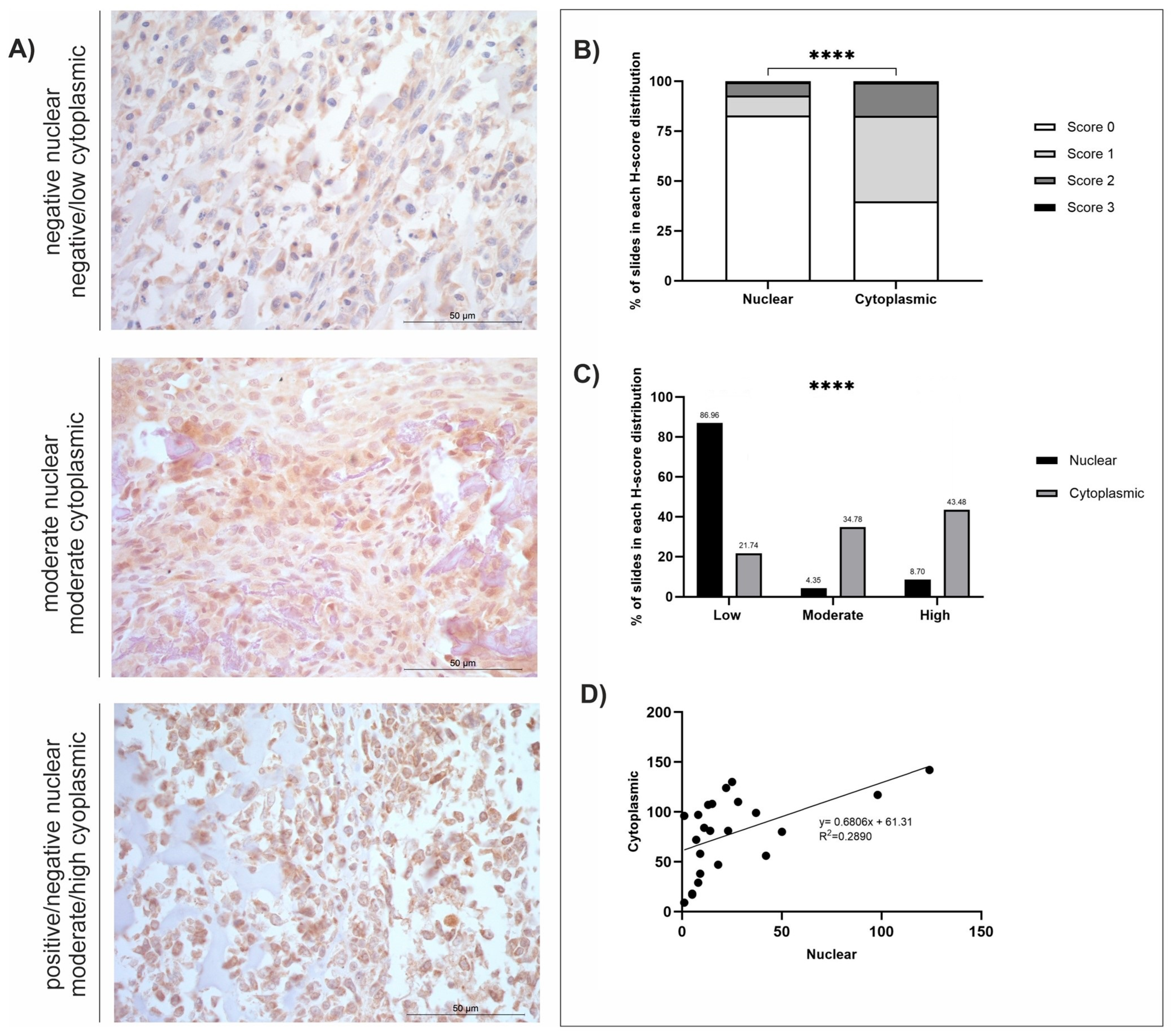

3.4. MMP-12

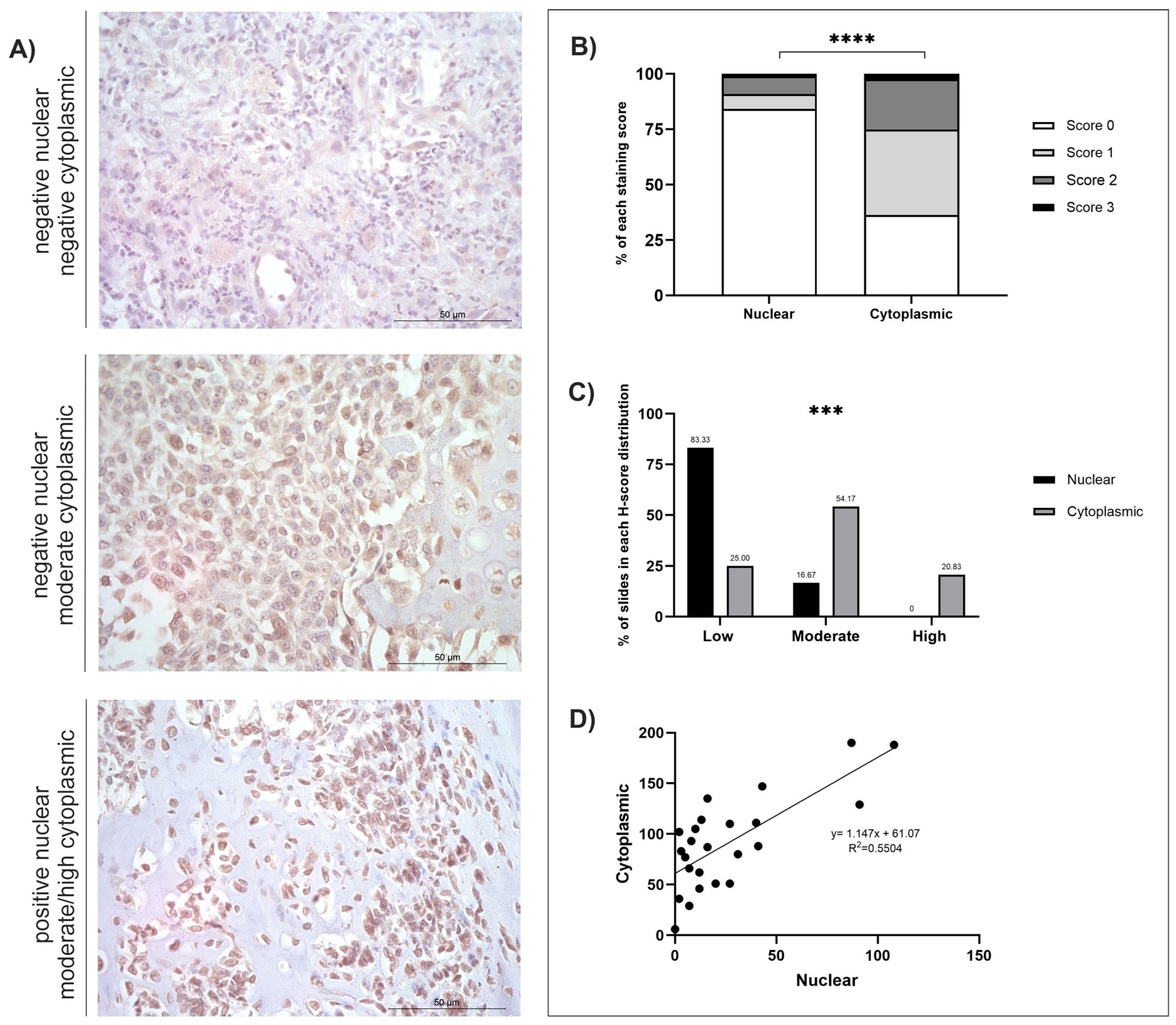

3.5. FOXF1

4. Discussion

4.1. GPR64

4.2. TOX3

4.3. MMP-12

4.4. FOXF1

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABCG2 | ATP Binding Cassette Subfamily G Member 2 |

| ATRA | All trans retinoic acid |

| BMP | Bone Morphogenetic Protein |

| CAF | Cancer-Associated Fibroblast |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| EMT | Epithelial–mesenchymal transition |

| ER | Oestrogen receptor |

| FFPE | Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded |

| FGF4 | Fibroblast Growth Factor 4 |

| FOXF1 | Forkhead Box F1 |

| FP-025 | Aderamastat |

| GPCR | G protein-coupled receptor |

| GPR64 | Adhesion G Protein-Coupled Receptor G2/ADGRG2 |

| HCC | Hepatocellular Carcinoma |

| HDAC | Histone deacetylases |

| HER2 | Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 |

| HMG-(box) | High Mobility Group- (box) |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| LOX | Lysyl oxidase |

| LUAD | Lung Adenocarcinoma |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MMP-12 | Matrix Metalloproteinase-12 |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| OSA | Osteosarcoma |

| PR | Progesterone receptor |

| SEM | Standard error mean |

| SMOC | SPARC-related modular calcium-binding protein |

| TAM | Tumour-associated macrophage |

| TOX3 | TOX High Mobility Group Box Family Member 3 |

| TPM | Transcripts per million |

References

- Rowell, J.L.; McCarthy, D.O.; Alvarez, C.E. Dog models of naturally occurring cancer. Trends Mol. Med. 2011, 17, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makielski, K.M.; Mills, L.J.; Sarver, A.L.; Henson, M.S.; Spector, L.G.; Naik, S.; Modiano, J.F. Risk Factors for Development of Canine and Human Osteosarcoma: A Comparative Review. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmunds, G.L.; Smalley, M.J.; Beck, S.; Errington, R.J.; Gould, S.; Winter, H.; Brodbelt, D.C.; O’Neill, D.G. Dog breeds and body conformations with predisposition to osteosarcoma in the UK: A case-control study. Canine Med. Genet. 2021, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, G.; Terracini, B.; Glickman, L.T. Host related risk factors for canine osteosarcoma. Vet. J. 1998, 156, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salt, C.; Morris, P.J.; German, A.J.; Wilson, D.; Lund, E.M.; Cole, T.J.; Butterwick, R.F. Growth standard charts for monitoring bodyweight in dogs of different sizes. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, S.; Dunning, M.D.; de Brot, S.; Grau-Roma, L.; Mongan, N.P.; Rutland, C.S. Comparative review of human and canine osteosarcoma: Morphology, epidemiology, prognosis, treatment and genetics. Acta Vet. Scand. 2017, 59, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, S.; Rizvanov, A.A.; Jeyapalan, J.N.; de Brot, S.; Rutland, C.S. Canine osteosarcoma in comparative oncology: Molecular mechanisms through to treatment discovery. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 965391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batcher, K.; Dickinson, P.; Maciejczyk, K.; Brzeski, K.; Rasouliha, S.H.; Letko, A.; Drogemuller, C.; Leeb, T.; Bannasch, D. Multiple FGF4 Retrocopies Recently Derived within Canids. Genes 2020, 11, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, E.A.; Dickinson, P.J.; Mansour, T.; Sturges, B.K.; Aguilar, M.; Young, A.E.; Korff, C.; Lind, J.; Ettinger, C.L.; Varon, S.; et al. FGF4 retrogene on CFA12 is responsible for chondrodystrophy and intervertebral disc disease in dogs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 11476–11481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morello, E.; Martano, M.; Buracco, P. Biology, diagnosis and treatment of canine appendicular osteosarcoma: Similarities and differences with human osteosarcoma. Vet. J. 2011, 189, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, D.G.; Edmunds, G.L.; Urquhart-Gilmore, J.; Church, D.B.; Rutherford, L.; Smalley, M.J.; Brodbelt, D.C. Dog breeds and conformations predisposed to osteosarcoma in the UK: A VetCompass study. Canine Med. Genet. 2023, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchant, T.W.; Johnson, E.J.; McTeir, L.; Johnson, C.I.; Gow, A.; Liuti, T.; Kuehn, D.; Svenson, K.; Bermingham, M.L.; Drogemuller, M.; et al. Canine Brachycephaly Is Associated with a Retrotransposon-Mediated Missplicing of SMOC2. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, 1573–1584.e1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boerman, I.; Selvarajah, G.T.; Nielen, M.; Kirpensteijn, J. Prognostic factors in canine appendicular osteosarcoma—A meta-analysis. BMC Vet. Res. 2012, 8, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szewczyk, M.; Lechowski, R.; Zabielska, K. What do we know about canine osteosarcoma treatment? Review. Vet. Res. Commun. 2015, 39, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacEwen, E.G.; Kurzman, I.D. Canine osteosarcoma: Amputation and chemoimmunotherapy. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 1996, 26, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorlick, R.; Khanna, C. Osteosarcoma. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2010, 25, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadykova, L.R.; Ntekim, A.I.; Muyangwa-Semenova, M.; Rutland, C.S.; Jeyapalan, J.N.; Blatt, N.; Rizvanov, A.A. Epidemiology and Risk Factors of Osteosarcoma. Cancer Investig. 2020, 38, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenger, J.M.; London, C.A.; Kisseberth, W.C. Canine osteosarcoma: A naturally occurring disease to inform pediatric oncology. ILAR J. 2014, 55, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, Z.S. Classification, imaging, biopsy and staging of osteosarcoma. Indian J. Orthop. 2014, 48, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miwa, S.; Shirai, T.; Yamamoto, N.; Hayashi, K.; Takeuchi, A.; Igarashi, K.; Tsuchiya, H. Current and Emerging Targets in Immunotherapy for Osteosarcoma. J. Oncol. 2019, 2019, 7035045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Chen, G.; Wang, D. Emerging immunotherapies in osteosarcoma: From checkpoint blockade to cellular therapies. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1579822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straw, R.C.; Withrow, S.J. Limb-sparing surgery versus amputation for dogs with bone tumors. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 1996, 26, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, J. Canine osteosarcoma: Amputation and chemotherapy. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 1996, 26, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, B.; Powers, B.E.; Dernell, W.S.; Straw, R.C.; Khanna, C.; Hogge, G.S.; Vail, D.M. Use of single-agent carboplatin as adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapy in conjunction with amputation for appendicular osteosarcoma in dogs. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 2009, 45, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duraiyan, J.; Govindarajan, R.; Kaliyappan, K.; Palanisamy, M. Applications of immunohistochemistry. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2012, 4, S307–S309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Z.; Luo, D.; Wang, S.; Rong, R.; Evers, B.M.; Jia, L.; Fang, Y.; Daoud, E.V.; Yang, S.; Gu, Z.; et al. Deep Learning-Based H-Score Quantification of Immunohistochemistry-Stained Images. Mod. Pathol. 2024, 37, 100398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aviles-Salas, A.; Muniz-Hernandez, S.; Maldonado-Martinez, H.A.; Chanona-Vilchis, J.G.; Ramirez-Tirado, L.A.; HernaNdez-Pedro, N.; Dorantes-Heredia, R.; Rui, Z.M.J.M.; Motola-Kuba, D.; Arrieta, O. Reproducibility of the EGFR immunohistochemistry scores for tumor samples from patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 13, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allott, E.H.; Cohen, S.M.; Geradts, J.; Sun, X.; Khoury, T.; Bshara, W.; Zirpoli, G.R.; Miller, C.R.; Hwang, H.; Thorne, L.B.; et al. Performance of Three-Biomarker Immunohistochemistry for Intrinsic Breast Cancer Subtyping in the AMBER Consortium. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2016, 25, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, S.; Dunning, M.; de Brot, S.; Alibhai, A.; Bailey, C.; Woodcock, C.L.; Mestas, M.; Akhtar, S.; Jeyapalan, J.N.; Lothion-Roy, J.; et al. Molecular Characterisation of Canine Osteosarcoma in High Risk Breeds. Cancers 2020, 12, 2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad, A.A.; Balenga, N. The Emerging Role of Adhesion GPCRs in Cancer. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2020, 3, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Sun, P.; Siwko, S.; Liu, M.; Xiao, J. The role of GPCRs in bone diseases and dysfunctions. Bone Res. 2019, 7, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Asanuma, K.; Okamoto, T.; Yoshida, K.; Matsuyama, Y.; Kita, K.; Hagi, T.; Nakamura, T.; Sudo, A. GPR64, Screened from Ewing Sarcoma Cells, Is a Potential Target for Antibody-Based Therapy for Various Sarcomas. Cancers 2022, 14, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Gao, P.; Li, Z. Expression of G Protein-coupled Receptor 56 Is an Unfavorable Prognostic Factor in Osteosarcoma Patients. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2016, 239, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, G.; Zhao, C.; Li, J. Clinical Significance of G Protein-Coupled Receptor 110 (GPR110) as a Novel Prognostic Biomarker in Osteosarcoma. Med. Sci. Monit. 2018, 24, 5216–5224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, J.; Huang, J.; Hua, C.; Zuo, Y.; Yu, W.; Wu, X.; Li, L.; Xue, G.; Wan, X.; Ru, L.; et al. A novel TOX3-WDR5-ABCG2 signaling axis regulates the progression of colorectal cancer by accelerating stem-like traits and chemoresistance. PLoS Biol. 2023, 21, e3002256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, H.; Yuan, B.; Huang, Y.; Wang, L.; He, B.; Sun, Q.; Sun, L. High expression of ABCG2 is associated with chemotherapy resistance of osteosarcoma. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2021, 16, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Bae, S.C. Histone deacetylase inhibitors: Molecular mechanisms of action and clinical trials as anti-cancer drugs. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2011, 3, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Health, S.C.A. TOX3 Inhibitors. Available online: https://www.scbt.com/browse/tox3-inhibitors (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Zhang, W.; Li, G.S.; Gan, X.Y.; Huang, Z.G.; He, R.Q.; Huang, H.; Li, D.M.; Tang, Y.L.; Tang, D.; Zou, W.; et al. MMP12 serves as an immune cell-related marker of disease status and prognosis in lung squamous cell carcinoma. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elshimi, E.; Sakr, M.A.M.; Morad, W.S.; Mohammad, L. Optimizing the Diagnostic Role of Alpha-Fetoprotein and Abdominal Ultrasound by Adding Overexpressed Blood mRNA Matrix Metalloproteinase-12 for Diagnosis of HCV-Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastrointest. Tumors 2019, 5, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucker, S.; Vacirca, J. Role of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in colorectal cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2004, 23, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.S.; Tang, Y.X.; Zhang, W.; Li, J.D.; Huang, H.Q.; Liu, J.; Fu, Z.W.; He, R.Q.; Kong, J.L.; Zhou, H.F.; et al. MMP12 is a Potential Predictive and Prognostic Biomarker of Various Cancers Including Lung Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Control 2024, 31, 10732748241235468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Xian, M.; Xiang, S.; Xiang, D.; Shao, X.; Wang, J.; Cao, J.; Yang, X.; Yang, B.; Ying, M.; et al. All-Trans Retinoic Acid Prevents Osteosarcoma Metastasis by Inhibiting M2 Polarization of Tumor-Associated Macrophages. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2017, 5, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elaziz, K.; Voors-Pette, C.; Wang, K.L.; Pan, S.; Lee, Y.; Mao, J.; Li, Y.; Chien, B.; Lau, D.; Diamant, Z. First-in-Man Safety, Tolerability, and Pharmacokinetics of a Novel and Highly Selective Inhibitor of Matrix Metalloproteinase-12, FP-025: Results from Two Randomized Studies in Healthy Subjects. Clin. Drug Investig. 2021, 41, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elaziz, K.S.; Cheng, R.; Chen, J.; Maarse, H.; Lee, Y.; Yang, W.; Chien, B.; Diamant, Z.; Kosterink, J.; Touw, D.J. Validation of a method for the determination of Aderamastat (FP-025) in K(2)EDTA human plasma by LC-MS/MS. J. Chromatogr. B 2024, 1245, 124244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahl, R.; Titlestad, I.; Lindqvist, A.; Wielders, P.; Wray, H.; Wang, M.; Samuelsson, V.; Mo, J.; Holt, A. Effects of an oral MMP-9 and -12 inhibitor, AZD1236, on biomarkers in moderate/severe COPD: A randomised controlled trial. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 25, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, K.-P.; Zhang, C.-L.; Ma, X.-L. Antisense lncRNA FOXF1-AS1 Promotes Migration and Invasion of Osteosarcoma Cells Through the FOXF1/MMP-2/-9 Pathway. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2017, 13, 1180–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, G.; Kannius-Janson, M. Forkhead Box F1 promotes breast cancer cell migration by upregulating lysyl oxidase and suppressing Smad2/3 signaling. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, P.K.; Lee, J.S.; Liang, X.; Han, L.; Mori, T.; Fackler, M.J.; Sadik, H.; Argani, P.; Pandita, T.K.; Sukumar, S. Epigenetic inactivation of the potential tumor suppressor gene FOXF1 in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 6047–6058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Invitrogen. Invitrogen™ GPR64 Polyclonal Antibody. Available online: https://www.fishersci.com/shop/products/gpr64-polyclonal-antibody-3/PIPA565594 (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Invitrogen. Invitrogen™ TOX3 Polyclonal Antibody. Available online: https://www.fishersci.com/shop/products/tox3-polyclonal-antibody-1/PIPA559151 (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Proteintech. MMP12 Polyclonal Antibody. Available online: https://www.ptglab.com/products/MMP12-Antibody-22989-1-AP.htm?srsltid=AfmBOopYMXoeigvrb-Zm__blkhgqIiNhVFgr8_7j05_Q5G-W06b3oQam (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Invitrogen. FOXF1 Polyclonal Antibody. Available online: https://www.thermofisher.com/antibody/product/FOXF1-Antibody-Polyclonal/PA5-40516 (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Shan, G.; Gerstenberger, S. Fisher’s exact approach for post hoc analysis of a chi-squared test. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0188709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerami, E.; Gao, J.; Dogrusoz, U.; Gross, B.E.; Sumer, S.O.; Aksoy, B.A.; Jacobsen, A.; Byrne, C.J.; Heuer, M.L.; Larsson, E.; et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: An open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2012, 2, 401–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutland, C.S.; Cockcroft, J.M.; Lothion-Roy, J.; Harris, A.E.; Jeyapalan, J.N.; Simpson, S.; Alibhai, A.; Bailey, C.; Ballard-Reisch, A.C.; Rizvanov, A.A.; et al. Immunohistochemical Characterisation of GLUT1, MMP3 and NRF2 in Osteosarcoma. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 704598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson-Oxley, J.; Alibhai, A.A.; Guerin, J.; Thompson, R.; Patke, R.; Harris, A.E.; Woodcock, C.L.; Varun, D.; Haque, M.; Modikoane, T.K.; et al. Comparison of Differentially Expressed Genes in Human and Canine Osteosarcoma. Life 2025, 15, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brot, S.; Cobb, J.; Alibhai, A.A.; Jackson-Oxley, J.; Haque, M.; Patke, R.; Harris, A.E.; Woodcock, C.L.; Lothion-Roy, J.; Varun, D.; et al. Immunohistochemical Investigation into Protein Expression Patterns of FOXO4, IRF8 and LEF1 in Canine Osteosarcoma. Cancers 2024, 16, 1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obermann, H.; Samalecos, A.; Osterhoff, C.; Schroder, B.; Heller, R.; Kirchhoff, C. HE6, a two-subunit heptahelical receptor associated with apical membranes of efferent and epididymal duct epithelia. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2003, 64, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlen, M.; Oksvold, P.; Fagerberg, L.; Lundberg, E.; Jonasson, K.; Forsberg, M.; Zwahlen, M.; Kampf, C.; Wester, K.; Hober, S.; et al. Towards a knowledge-based Human Protein Atlas. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 1248–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gough, N.R. G Protein-Coupled Receptor Signaling in the Nucleus. Sci. Signal. 2008, 1, ec181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, M.C.; Fokkelman, M.; Boogaard, B.; Egerod, K.L.; van de Water, B.; AP, I.J.; Schwartz, T.W. The adhesion G protein-coupled receptor G2 (ADGRG2/GPR64) constitutively activates SRE and NFkappaB and is involved in cell adhesion and migration. Cell Signal 2015, 27, 2579–2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves-Monteiro, S.; Ribeiro-Oliveira, R.; Vieira-Rocha, M.S.; Vojtek, M.; Sousa, J.B.; Diniz, C. Insights into Nuclear G-Protein-Coupled Receptors as Therapeutic Targets in Non-Communicable Diseases. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro-Oliveira, R.; Vojtek, M.; Goncalves-Monteiro, S.; Vieira-Rocha, M.S.; Sousa, J.B.; Goncalves, J.; Diniz, C. Nuclear G-protein-coupled receptors as putative novel pharmacological targets. Drug Discov. Today 2019, 24, 2192–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suvarna, K.; Jayabal, P.; Ma, X.; Wang, H.; Chen, Y.; Weintraub, S.T.; Han, X.; Houghton, P.J.; Shiio, Y. Ceramide-induced cleavage of GPR64 intracellular domain drives Ewing sarcoma. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 114497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Li, Z. TOX gene: A novel target for human cancer gene therapy. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2015, 5, 3516–3524. [Google Scholar]

- Malarkey, C.S.; Churchill, M.E. The high mobility group box: The ultimate utility player of a cell. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2012, 37, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Flaherty, E.; Kaye, J. TOX defines a conserved subfamily of HMG-box proteins. BMC Genom. 2003, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stros, M. HMGB proteins: Interactions with DNA and chromatin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1799, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobin, B.; Moriceau, G.; Ory, B.; Charrier, C.; Brion, R.; Blanchard, F.; Redini, F.; Heymann, D. Imatinib mesylate exerts anti-proliferative effects on osteosarcoma cells and inhibits the tumour growth in immunocompetent murine models. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacy, A.E.; Jansson, P.J.; Richardson, D.R. Molecular pharmacology of ABCG2 and its role in chemoresistance. Mol. Pharmacol. 2013, 84, 655–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amuti, A.; Liu, D.; Maimaiti, A.; Yu, Y.; Yasen, Y.; Ma, H.; Li, R.; Deng, S.; Pang, F.; Tian, Y. Doxorubicin inhibits osteosarcoma progression by regulating circ_0000006/miR-646/BDNF axis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2021, 16, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salazar, J.; Arranz, M.J.; Martin-Broto, J.; Bautista, F.; Martinez-Garcia, J.; Martinez-Trufero, J.; Vidal-Insua, Y.; Echebarria-Barona, A.; Diaz-Beveridge, R.; Valverde, C.; et al. Pharmacogenetics of Neoadjuvant MAP Chemotherapy in Localized Osteosarcoma: A Study Based on Data from the GEIS-33 Protocol. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Yu, J.; Liu, F.; Tang, L.; Li, B.; Zhang, W.; Chen, K.; Zhang, H.; Wei, Y.; Ma, X.; et al. Accumulation of TOX high mobility group box family member 3 promotes the oncogenesis and development of hepatocellular carcinoma through the MAPK signaling pathway. MedComm 2024, 5, e510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiden, E.E.; Richardson, S.M.; Everitt, L.A.; Knafler, G.J.; Kinsella, G.P.; Walker, A.L.; Whiteside, V.A.; Buschbach, J.D.; Gandhi, D.A.; Saadatzadeh, M.R.; et al. Repurposing Romidepsin for Osteosarcoma: Screening FDA-Approved Oncology Drugs with Three-Dimensional Osteosarcoma Spheroids. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntschar, S.; Cardamone, G.; Klann, K.; Bauer, R.; Meyer, S.P.; Raue, R.; Rappl, P.; Munch, C.; Brune, B.; Schmid, T. Mmp12 Is Translationally Regulated in Macrophages during the Course of Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbardella, D.; Fasciglione, G.F.; Gioia, M.; Ciaccio, C.; Tundo, G.R.; Marini, S.; Coletta, M. Human matrix metalloproteinases: An ubiquitarian class of enzymes involved in several pathological processes. Mol. Aspects Med. 2012, 33, 119–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Lo, W.C.; Majumder, P.; Roy, D.; Ghorai, M.; Shaikh, N.K.; Kant, N.; Shekhawat, M.S.; Gadekar, V.S.; Ghosh, S.; et al. Multiple roles for basement membrane proteins in cancer progression and EMT. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2022, 101, 151220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcos-Jubilar, M.; Orbe, J.; Roncal, C.; Machado, F.J.D.; Rodriguez, J.A.; Fernandez-Montero, A.; Colina, I.; Rodil, R.; Pastrana, J.C.; Paramo, J.A. Association of SDF1 and MMP12 with Atherosclerosis and Inflammation: Clinical and Experimental Study. Life 2021, 11, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, P.P.; Ding, W.Y.; Wang, P. The roles of prostaglandin F(2) in regulating the expression of matrix metalloproteinase-12 via an insulin growth factor-2-dependent mechanism in sheared chondrocytes. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2018, 3, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral-Pacheco, G.A.; Garza-Veloz, I.; Castruita-De la Rosa, C.; Ramirez-Acuna, J.M.; Perez-Romero, B.A.; Guerrero-Rodriguez, J.F.; Martinez-Avila, N.; Martinez-Fierro, M.L. The Roles of Matrix Metalloproteinases and Their Inhibitors in Human Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, F.Z.; Wang, J.L.; Wu, Y.; Chen, H.F.; Shen, X.Y. Knockdown of MMP12 inhibits the growth and invasion of lung adenocarcinoma cells. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2015, 28, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørnerem, Å.; Bui, Q.M.; Ghasem-Zadeh, A.; Hopper, J.L.; Zebaze, R.; Seeman, E. Fracture risk and height: An association partly accounted for by cortical porosity of relatively thinner cortices. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2013, 28, 2017–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhakeem, A.; Frysz, M.; Tilling, K.; Tobias, J.H.; Lawlor, D.A. Association Between Age at Puberty and Bone Accrual from 10 to 25 Years of Age. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e198918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, T.J.; Kuh, D.; Johnson, W.; Ward, K.A.; Howe, L.D.; Adams, J.E.; Hardy, R.; Ong, K.K. Using Super-Imposition by Translation And Rotation (SITAR) to relate pubertal growth to bone health in later life: The Medical Research Council (MRC) National Survey of Health and Development. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 45, 1125–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinar-Gutierrez, A.; Garcia-Fontana, C.; Garcia-Fontana, B.; Munoz-Torres, M. Obesity and Bone Health: A Complex Relationship. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caley, M.P.; Martins, V.L.; O’Toole, E.A. Metalloproteinases and Wound Healing. Adv. Wound Care 2015, 4, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerzeli, I.K.; Kostakis, A.; Turker, P.; Malmstrom, P.U.; Hemdan, T.; Mezheyeuski, A.; Ward, D.G.; Bryan, R.T.; Segersten, U.; Lord, M.; et al. Elevated levels of MMP12 sourced from macrophages are associated with poor prognosis in urothelial bladder cancer. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adell, T.; Muller, W.E. Isolation and characterization of five Fox (Forkhead) genes from the sponge Suberites domuncula. Gene 2004, 334, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golson, M.L.; Kaestner, K.H. Fox transcription factors: From development to disease. Development 2016, 143, 4558–4570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Liao, X.; Lin, L.; Wu, L.; Tang, Q. FOXF1 attenuates TGF-beta1-induced bronchial epithelial cell injury by inhibiting CDH11-mediated Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Exp. Ther. Med. 2023, 25, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doppelt-Flikshtain, O.; Asbi, T.; Younis, A.; Ginesin, O.; Cohen, Z.; Tamari, T.; Berg, T.; Yanovich, C.; Aran, D.; Zohar, Y.; et al. Inhibition of osteosarcoma metastasis in vivo by targeted downregulation of MMP1 and MMP9. Matrix Biol. 2024, 134, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Liu, H.; Yu, K.; Liu, Y. Matrix metalloproteinase 2 expression and survival of patients with osteosarcoma: A meta-analysis. Tumour Biol. 2014, 35, 845–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, M.; Sasaki, Y.; Koyama, R.; Takeda, K.; Idogawa, M.; Tokino, T. Forkhead transcription factor FOXF1 is a novel target gene of the p53 family and regulates cancer cell migration and invasiveness. Oncogene 2014, 33, 4837–4846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, R.A.; Micke, P.; Paulsson, J.; Augsten, M.; Pena, C.; Jonsson, P.; Botling, J.; Edlund, K.; Johansson, L.; Carlsson, P.; et al. Forkhead box F1 regulates tumor-promoting properties of cancer-associated fibroblasts in lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 2644–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madison, B.B.; McKenna, L.B.; Dolson, D.; Epstein, D.J.; Kaestner, K.H. FoxF1 and FoxL1 link hedgehog signaling and the control of epithelial proliferation in the developing stomach and intestine. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 5936–5944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Z.; Quazi, S.; Arora, S.; Osellame, L.D.; Burvenich, I.J.; Janes, P.W.; Scott, A.M. Cancer-associated fibroblasts as therapeutic targets for cancer: Advances, challenges, and future prospects. J. Biomed. Sci. 2025, 32, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothzerg, E.; Xu, J.; Wood, D. Different Subtypes of Osteosarcoma: Histopathological Patterns and Clinical Behaviour. J. Mol. Pathol. 2023, 4, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Jiang, X.; Miao, J.; Feng, W.; Xie, T.; Liao, S.; Qin, Z.; Tang, H.; Lin, C.; Li, B.; et al. A new insight of immunosuppressive microenvironment in osteosarcoma lung metastasis. Exp. Biol. Med. 2023, 248, 1056–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Protein (no. of Cases) | Staining Distribution (Diffuse/Multifocal/Focal) | Cellular Location | H-Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SEM (2 s.f) | Range (min–max) | |||

| GPR64 (n = 20) | Diffuse | Nuclear | 113.38 ± 9.58 | 5–191 |

| Cytoplasmic | 89.10 ± 7.61 | 14–163 | ||

| TOX3 (n = 24) | Diffuse | Nuclear | 33.16 ± 6.25 | 0–104 |

| Cytoplasmic | 77.83 ± 7.61 | 5–144 | ||

| MMP-12 (n = 23) | Diffuse | Nuclear | 24.38 ± 6.07 | 1–124 |

| Cytoplasmic | 78.38 ± 7.66 | 9–142 | ||

| FOXF1 (n = 24) | Diffuse | Nuclear | 26.17 ± 6.06 | 0–108 |

| Cytoplasmic | 91.08 ± 9.38 | 6–190 | ||

| Nuclear | Cytoplasmic | ||||

| Absent | Low | Moderate | High | ||

| [GPR64, n = 20] | |||||

| Absent | - | - | - | - | |

| Low | - | 2 (10.00%) | - | - | |

| Moderate | - | 1 (5.00%) | 7 (35.00%) | - | |

| High | - | 1 (5.00%) | 8 (40.00%) | 1 (5.00%) | |

| [TOX3, n = 24] | |||||

| Absent | - | 1 (4.17%) | - | - | |

| Low | - | 4 (16.67%) | 8 (33.33%) | 3 (12.50%) | |

| Moderate | - | - | 2 (8.33%) | 5 (20.83%) | |

| High | - | - | - | 1 (1.47%) | |

| [MMP-12, n = 23] | |||||

| Absent | - | - | - | - | |

| Low | - | 5 (21.74%) | 7 (30.43%) | 8 (34.78%) | |

| Moderate | - | - | 1 (4.35%) | - | |

| High | - | - | - | 2 (8.70%) | |

| [FOXF1, n = 24] | |||||

| Absent | - | 1 (4.17%) | - | - | |

| Low | - | 5 (20.83%) | 12 (50.00%) | 2 (8.33%) | |

| Moderate | - | - | 1 (4.17%) | 3 (12.50%) | |

| High | - | - | - | - | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jackson-Oxley, J.; Alibhai, A.A.; Thompson, R.; Lothion-Roy, J.; de Brot, S.; Dunning, M.D.; Jeyapalan, J.N.; Mongan, N.P.; Rutland, C.S. Identification and Characterisation of Canine Osteosarcoma Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets. Cancers 2026, 18, 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020262

Jackson-Oxley J, Alibhai AA, Thompson R, Lothion-Roy J, de Brot S, Dunning MD, Jeyapalan JN, Mongan NP, Rutland CS. Identification and Characterisation of Canine Osteosarcoma Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets. Cancers. 2026; 18(2):262. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020262

Chicago/Turabian StyleJackson-Oxley, Jorja, Aziza A. Alibhai, Rachel Thompson, Jennifer Lothion-Roy, Simone de Brot, Mark D. Dunning, Jennie N. Jeyapalan, Nigel P. Mongan, and Catrin S. Rutland. 2026. "Identification and Characterisation of Canine Osteosarcoma Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets" Cancers 18, no. 2: 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020262

APA StyleJackson-Oxley, J., Alibhai, A. A., Thompson, R., Lothion-Roy, J., de Brot, S., Dunning, M. D., Jeyapalan, J. N., Mongan, N. P., & Rutland, C. S. (2026). Identification and Characterisation of Canine Osteosarcoma Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets. Cancers, 18(2), 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020262