Effect of Race and Tumor Subsite on Survival Outcome in Early- and Late-Onset Colorectal Cancer

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Study Cohort

2.2. Sociodemographic and Clinical Variables

2.3. Survival Endpoints

2.4. Statistical Analysis

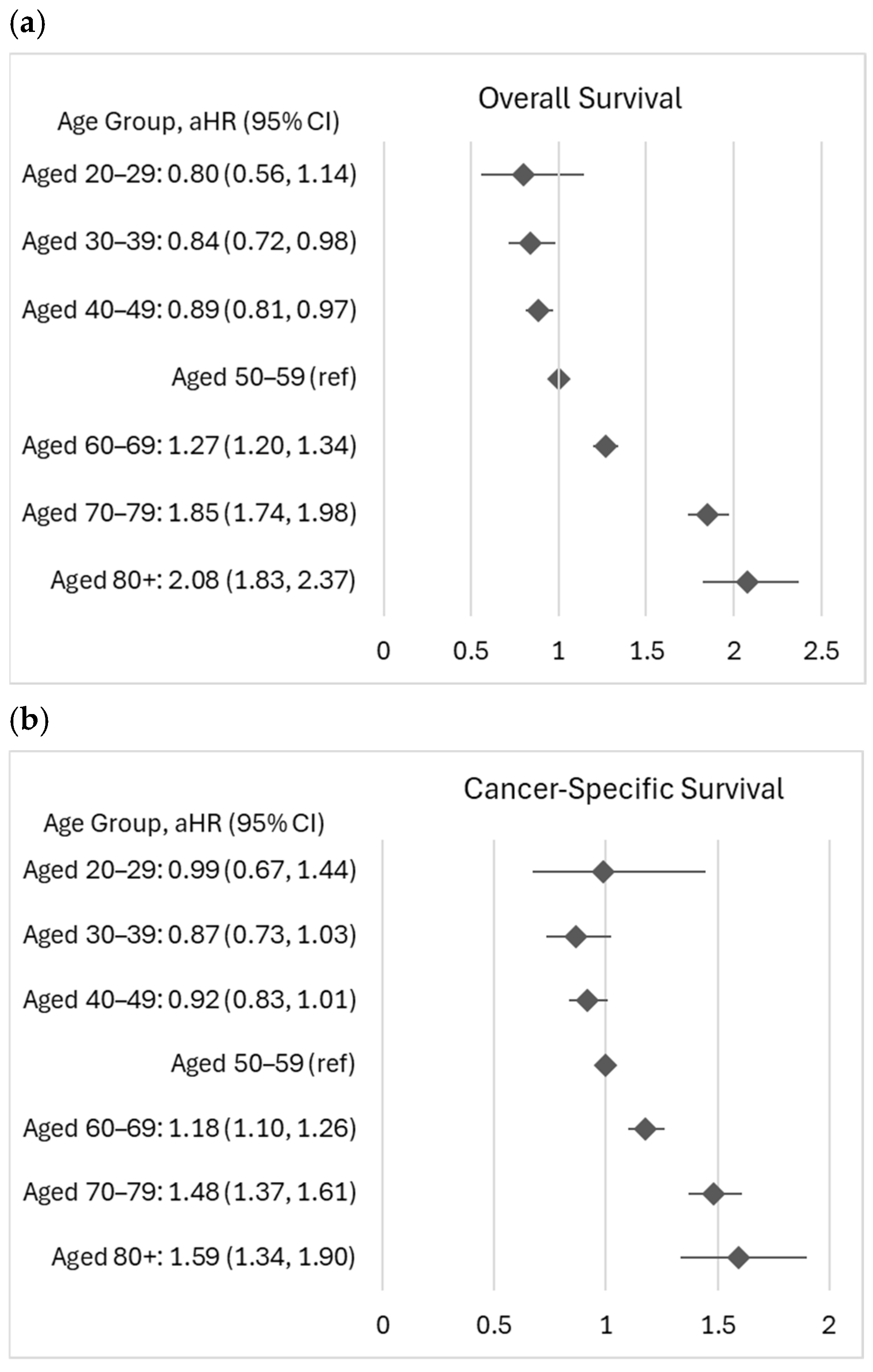

3. Results

3.1. Racial Differences in Survival

3.2. Anatomic Subsite Differences in Survival

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Kratzer, T.B.; Giaquinto, A.N. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2025, 75, 10–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustus, G.J.; Ellis, N.A. Colorectal Cancer Disparity in African Americans Risk Factors and Carcinogenic Mechanisms. Am. J. Pathol. 2018, 188, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawla, P.; Sunkara, T.; Barsouk, A. Epidemiology of colorectal cancer: Incidence, mortality, survival, and risk factors. Prz. Gastroenterol. 2019, 14, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Wagle, N.S.; Cercek, A.; Smith, R.A.; Jemal, A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 233–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louisiana Cancer Data Visualization, Based on November 2023 Submission Data (2017–2021): Louisiana Tumor Registry. December 2024. Available online: https://sph.lsuhsc.edu/louisiana-tumor-registry/data-usestatistics/louisiana-cancer-data-visualization-dashboard (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Saad El Din, K.; Loree, J.M.; Sayre, E.C.; Gill, S.; Brown, C.J.; Dau, H.; De Vera, M.A. Trends in the epidemiology of young-onset colorectal cancer: A worldwide systematic review. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akimoto, N.; Ugai, T.; Zhong, R.; Hamada, T.; Fujiyoshi, K.; Giannakis, M.; Wu, K.; Cao, Y.; Ng, K.; Ogino, S. Rising incidence of early-onset colorectal cancer: A call for action. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 18, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Jiang, C.; Morgan, E.; Zahwe, M.; Cao, Y.; Bray, F.; Jemal, A. Colorectal cancer incidence trends in younger versus older adults: An analysis of population-based cancer registry data. Lancet Oncol. 2025, 26, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffel, E.M.; Koeppe, E.; Everett, J.; Ulintz, P.; Kiel, M.; Osborne, J.; Williams, L.; Hanson, K.; Gruber, S.B.; Rozek, L.S. Germline Genetic Features of Young Individuals with Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology 2018, 154, 897–905.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaander, M.C.W.; Zauber, A.G.; Syngal, S.; Blaser, M.J.; Sung, J.J.; You, Y.N.; Kuipers, E.J. Young-onset Colorectal Cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2023, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snider-Hoy, N.G.; Buchalter, R.B.; Hastert, T.A.; Dyson, G.; Gronlund, C.; Ruterbusch, J.J.; Schwartz, A.G.; Stoffel, E.M.; Rozek, L.S.; Purrington, K.S. Social–Environmental Burden Is Associated with Increased Colorectal Cancer Mortality in Metropolitan Detroit. Cancer Res. Commun. 2025, 5, 694–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, E.; Blackburn, H.N.; Ng, K.; Spiegeiman, D.; Irwin, M.L.; Ma, X.; Gross, C.P.; Tabung, F.K.; Giovannucci, E.L.; Kunz, P.L.; et al. Analysis of Survival Among Adults with Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer in the National Cancer Database. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2112539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawras, Y.; Merza, N.; Beier, K.; Beier, K.; Dakroub, A.; Al-Obaidi, H.; Al-Obaidi, A.D.; Amatul-Raheem, H.; Bahbah, E.; Varughese, T.; et al. Temporal Trends in Racial and Gender Disparities of Early Onset Colorectal Cancer in the United States: An Analysis of the CDC WONDER Database. J. Gastrointest. Cancer 2024, 55, 1511–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boakye, D.; Walter, V.; Jansen, L.; Martens, U.M.; Chang-Claude, J.; Hoffmeister, M.; Brenner, H. Magnitude of the Age-Advancement Effect of Comorbidities in Colorectal Cancer Prognosis. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2020, 18, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holowatyj, A.N.; Ruterbusch, J.J.; Rozek, L.S.; Cote, M.L.; Stoffel, E.M. Racial/ethnic disparities in survival among patients with young-onset colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 2148–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arshad, H.M.S.; Kabir, C.; Tetangco, A.E.; Shuh, N.; Raddawi, H. Racial Disparities in Clinical Presentation and Survival Times Among Young-Onset Colorectal Adenocarcinoma. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2017, 62, 2526–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Goding Sauer, A.; Fedewa, S.A.; Butterly, L.F.; Anderson, J.C.; Cercek, A.; Smith, R.A.; Jemal, A. Colorectal Cancer Statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, T.A.; Liang, P.S.; May, F.P.; Murphy, C.C. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer Survival. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 21, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Primm, K.M.; Malaby, A.J.; Curry, T.; Chang, S. Who, where, when: Colorectal cancer disparities by race and ethnicity, subsite, and stage. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 14767–14780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meguid, R.A.; Slidell, M.B.; Wolfgang, C.L.; Chang, D.C.; Ahuja, N. Is There a Difference in Survival Between Right-Versus Left-Sided Colon Cancers? Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2008, 15, 2388–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahagi, M.; Okabayashi, K.; Hasegawa, H.; Tsuruta, M.; Kitagawa, Y. The worse prognosis of right-sided compared with left-sided colon cancers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2016, 20, 648–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warschkow, R.; Sulz, M.C.; Marti, L.; Tarantino, I.; Schmied, B.M.; Cerny, T.; Güller, U. Better survival in right-sided versus left-sided stage I–III colon cancer patients. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.-K.; Wu, W.; Ding, Y.; Li, Y.; Sun, L.-M.; Si, J. Different Anatomical Subsites of Colon Cancer and Mortality: A Population-Based Study. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2018, 2018, 7153685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, C.C.; Wallace, K.; Sandler, R.S.; Baron, J.A. Racial disparities in incidence of young-onset colorectal cancer and patient survival. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 958–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, P.K.R.; Lam, N. An Environmental Justice Assessment Mississippi River Industrial Corridor in Louisiana, U.S. Using a GIS-based Approach. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2013, 11, 681–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.L., Jr.; Roffers, S.D.; Ries, L.A.G.; Fritz, A.G.; Hurlbut, A.A. (Eds.) SEER Summary Staging Manual—2000: Codes and Coding Instructions; NIH Pub. No. 01-4969; National Cancer Institute: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ruhl, J.L.; Callaghan, C.; Schussler, N. (Eds.) Summary Stage 2018: Codes and Coding Instructions; National Cancer Institute: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Quan, H.; Sundararajan, V.; Halfon, P.; Fong, A.; Burnand, B.; Luthi, J.C.; Saunders, L.D.; Beck, C.A.; Feasby, T.E.; Ghali, W.A. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med. Care 2005, 43, 1130–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SEER Cause-specific Death Classification. Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/causespecific/ (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Gervaz, P.; Bucher, P.; Morel, P. Two colons-two cancers: Paradigm shift and clinical implications. J. Surg. Oncol. 2004, 88, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akce, M.; Zakka, K.; Jiang, R.; Williamson, S.; Alese, O.B.; Shaib, W.L.; Wu, C.; Behera, M.; El-Rayes, B.F. Impact of tumor side on clinical outcomes in stage II and III colon cancer with known microsatellite instability status. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 592351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, T.; Kobunai, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Matsuda, K.; Ishihara, S.; Nozawa, K.; Yamada, H.; Hayama, T.; Inoue, E.; Tamura, J.; et al. Chromosomal Instability (CIN) Phenotype, CIN High or CIN Low, Predicts Survival for Colorectal Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 2256–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.S.; Menter, D.G.; Kopetz, S. Right Versus Left Colon Cancer Biology: Integrating the Consensus Molecular Subtypes. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2017, 15, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.; Goffredo, P.; Ginader, T.; Hrabe, J.; Gribovskaja-Rupp, I.; Kapadia, M.R.; Weigel, R.J.; Hassan, I. The Impact of KRAS Mutation on the Presentation and Prognosis of Non-Metastatic Colon Cancer: An Analysis from the National Cancer Database. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2020, 24, 1402–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacopetta, B. Are there two sides to colorectal cancer? Int. J. Cancer 2002, 101, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Therkildsen, C.; Bergmann, T.K.; Henrichsen-Schnack, T.; Ladelund, S.; Nilbert, M. The predictive value of KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA and PTEN for anti-EGFR treatment in metastatic colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Oncol. 2014, 53, 852–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myer, P.A.; Lee, J.K.; Madison, R.W.; Pradhan, K.; Newberg, J.Y.; Isasi, C.R.; Klempner, S.J.; Frampton, G.M.; Ross, J.S.; Venstrom, J.M.; et al. The Genomics of colorectal cancer in populations with African and European ancestry. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 1282–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, T.; Parlato, L.; Anderson, S.W. Racial disparities in colorectal cancer clinicopathological and molecular tumor characteristics: A systematic review. Cancer Causes Control 2024, 35, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, M.; Yoshida, S.; Inoue, T.; Sekido, Y.; Hata, T.; Hamabe, A.; Ogino, T.; Miyoshi, N.; Uemura, M.; Yamamoto, H.; et al. The role of KRAS mutations in colorectal cancer: Biological insights, clinical implications, and future therapeutic perspectives. Cancers 2025, 17, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hein, D.M.; Deng, W.; Bleile, M.; Kazmi, S.A.; Rhead, B.; De La Vega, F.M.; Jones, A.L.; Kainthla, R.; Jiang, W.; Cantarel, B.; et al. Racial and ethnic differences in genomic profiling of early onset colorectal cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2022, 114, 775–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieu, C.H.; Golemis, E.A.; Serebriiskii, I.G.; Newberg, J.; Hemmerich, A.; Connelly, C.; Messersmith, W.A.; Eng, C.; Eckhardt, G.; Frampton, G.; et al. Comprehensive genomic landscapes in early and later colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 5852–5858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, J.M.; Pfau, P.R.; O’Connor, E.S.; King, J.; LoConte, N.; Kennedy, G.; Smith, M.A. Mortality by stage for right-versus left-sided colon cancer: Analysis of surveillance, epidemiology, and end results–Medicare data. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 4401–4409. [Google Scholar]

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2021, 325, 1965–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buccafusca, G.; Proserpio, I.; Tralongo, A.C.; Giuliano, S.R.; Tralongo, P. Early colorectal cancer: Diagnosis, treatment and survivorship care. Crit. Rev. Oncol./Hematol. 2019, 136, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abboud, Y.; Fraser, M.; Qureshi, I.; Srivastava, S.; Abboud, I.; Richter, B.; Jaber, F.; Alsakarneh, S.; Al-Khazraji, A.; Hajifathalian, K. Geographical Variations in Early Onset Colorectal Cancer in the United States Between 2001 and 2020. Cancers 2024, 16, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fretwell, A.; Dobson, C.; Orange, S.T.; Corfe, B.M. Diet and physical activity advice for colorectal cancer survivors: Critical synthesis of public-facing guidance. Support. Care Cancer 2024, 32, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | N = 23,738 | EOCRC (N = 2530) | LOCRC (N = 21,208) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic Factors | ||||

| Race | <0.0001 | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 15,880 (66.9) | 1581 (62.49) | 14,299 (67.42) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 7858 (33.1) | 949 (37.51) | 6909 (32.58) | |

| Sex | <0.0001 | |||

| Male | 12,827 (54.0) | 1301 (51.42) | 11,526 (54.35) | |

| Female | 10,911 (46.0) | 1229 (48.58) | 9682 (45.65) | |

| Marital status | 0.4678 | |||

| Married | 11,491 (48.4) | 1224 (48.38) | 10,267 (48.41) | |

| Single | 11,130 (46.9) | 1199 (47.39) | 9931 (46.83) | |

| Unknown | 1117 (4.7) | 107 (4.23) | 1010 (4.76) | |

| Insurance | <0.0001 | |||

| Private insurance | 8752 (36.9) | 1477 (58.38) | 7275 (34.3) | |

| Medicare/other government | 9730 (41.0) | 170 (6.72) | 9560 (45.08) | |

| Medicaid | 3977 (16.8) | 663 (26.21) | 3314 (15.63) | |

| Uninsured/unknown | 1279 (5.4) | 220 (8.7) | 1059 (4.99) | |

| Census tract level poverty | 0.0262 | |||

| <10% | 4720 (19.9) | 537 (21.23) | 4183 (19.72) | |

| 10%–<20% | 9037 (38.1) | 990 (39.13) | 8047 (37.94) | |

| ≥20% | 9981 (42.0) | 1003 (39.64) | 8978 (42.33) | |

| Urban/Rural | 0.0760 | |||

| Urban | 19,494 (82.1) | 2110 (83.4) | 17,384 (81.97) | |

| Rural | 4244 (17.9) | 420 (16.6) | 3824 (18.03) | |

| Clinical Factors | ||||

| Site | <0.0001 | |||

| Proximal colon | 9794 (41.3) | 651 (25.73) | 9143 (43.11) | |

| Distal colon | 6483 (27.3) | 755 (29.84) | 5728 (27.01) | |

| Rectum | 7461 (31.4) | 1124 (44.43) | 6337 (29.88) | |

| SEER summary stage | <0.0001 | |||

| Localized | 9618 (40.5) | 853 (33.72) | 8765 (41.33) | |

| Regional | 8793 (37.0) | 997 (39.41) | 7796 (36.76) | |

| Distant | 5327 (22.4) | 680 (26.88) | 4647 (21.91) | |

| Grade | 0.4194 | |||

| Low | 17,152 (72.3) | 1837 (72.61) | 15,315 (72.21) | |

| High | 3560 (15.0) | 359 (14.19) | 3201 (15.09) | |

| Unknown | 3026 (12.7) | 334 (13.2) | 2692 (12.69) | |

| Tumor number | <0.0001 | |||

| Single primary site | 17,538 (73.9) | 2244 (88.7) | 15,294 (72.11) | |

| Multiple primary sites | 6200 (26.1) | 286 (11.3) | 5914 (27.89) | |

| Comorbidity | <0.0001 | |||

| None # | 16,070 (67.7) | 2131 (84.23) | 13,939 (65.73) | |

| CCI score = 1 | 4718 (19.9) | 302 (11.94) | 4416 (20.82) | |

| CCI score ≥ 2 | 2950 (12.4) | 97 (3.83) | 2853 (13.45) | |

| Treatment | ||||

| Surgery | 0.2735 | |||

| No | 3906 (16.5) | 397 (15.69) | 3509 (16.55) | |

| Yes | 19,832 (83.5) | 2133 (84.31) | 17,699 (83.45) | |

| Chemotherapy | <0.0001 | |||

| No | 12,713 (53.6) | 876 (34.62) | 11,837 (55.81) | |

| Yes | 10,019 (42.2) | 1565 (61.86) | 8454 (39.86) | |

| Unknown | 1006 (4.2) | 89 (3.52) | 917 (4.32) | |

| Radiation | <0.0001 | |||

| No | 19,884 (83.8) | 1902 (75.18) | 17,982 (84.79) | |

| Yes | 3549 (15.0) | 595 (23.52) | 2954 (13.93) | |

| Unknown | 305 (1.3) | 33 (1.3) | 272 (1.28) | |

| All-cause death | <0.0001 | |||

| Alive | 11,976 (50.5) | 1652 (65.3) | 10,324 (48.68) | |

| Death | 11,762 (49.5) | 878 (34.7) | 10,884 (51.32) | |

| 5-year survival rate% (95%CI) | 54.0 (53.4–54.7) | 65.1 (63.0–67.1) | 52.7 (52.0–53.5) | <0.0001 |

| Cancer-specific death | 0.0281 | |||

| Alive or died in other cause | 16,160 (68.1) | 1771 (70) | 14,389 (67.85) | |

| Died in cancer related cause | 7578 (31.9) | 759 (30) | 6819 (32.15) | |

| 5-year survival rate% (95%CI) | 65.8 (65.1–68.1) | 68.5 (66.4–70.4) | 65.5 (64.7–66.2) | <0.0001 |

| Model | Overall Survival | Cancer-Specific Survival | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EOCRC HR (95%CI) | LOCRC HR (95%CI) | EOCRC HR (95%CI) | LOCRC HR (95%CI) | |

| Race: NHW as reference | ||||

| Model 1—NHB | 1.307 (1.143–1.494) | 1.036 (0.995–1.078) | 1.269 (1.099–1.466) | 1.127 (1.072–1.184) |

| Model 2—NHB | 1.172 (1.006–1.367) | 0.987 (0.944–1.032) | 1.175 (0.996–1.385) | 1.007 (0.953–1.064) |

| Model 3—NHB | 1.110 (0.951–1.295) | 0.974 (0.931–1.018) | 1.101 (0.932–1.300) | 0.993 (0.939–1.050) |

| Model 4: Model 3 + race × site interaction | ||||

| Proximal: NHB | 0.943 (0.730–1.218) | 0.980 (0.921–1.044) | 0.946 (0.714–1.253) | 1.070 (0.989–1.158) |

| Distal: NHB | 1.254 (0.962–1.633) | 1.045 (0.966–1.131) | 1.358 (1.024–1.801) | 1.015 (0.918–1.122) |

| Rectal: NHB | 1.155 (0.920–1.451) | 0.899 (0.831–0.973) | 1.061 (0.829–1.357) | 0.873 (0.793–0.960) |

| Subsite: Distal colon as reference | ||||

| Model 1—Proximal | 1.297 (1.089–1.545) | 1.133 (1.082–1.186) | 1.221 (1.011–1.476) | 1.082 (1.020–1.148) |

| Model 1—Rectal | 1.028 (0.875–1.208) | 0.966 (0.918–1.016) | 1.034 (0.871–1.227) | 1.071 (1.005–1.140) |

| Model 2—Proximal | 1.215 (1.018–1.451) | 1.012 (0.965–1.061) | 1.155 (0.953–1.400) | 1.056 (0.995–1.122) |

| Model 2—Rectal | 1.190 (1.007–1.407) | 1.023 (0.972–1.077) | 1.213 (1.014–1.450) | 1.116 (1.047–1.189) |

| Model 3—Proximal | 1.225 (1.026–1.462) | 0.999 (0.953–1.047) | 1.162 (0.959–1.408) | 1.035 (0.974–1.099) |

| Model 3—Rectal | 1.176 (0.972–1.421) | 0.910 (0.859–0.964) | 1.184 (0.965–1.453) | 0.943 (0.878–1.014) |

| Model 4: Model 3 + race × site interaction | ||||

| NHW: Proximal | 1.407 (1.102–1.796) | 1.022 (0.964–1.082) | 1.379 (1.057–1.799) | 1.015 (0.941–1.094) |

| NHW: Rectal | 1.221 (0.967–1.543) | 0.958 (0.895–1.027) | 1.314 (1.022–1.690) | 0.995 (0.914–1.084) |

| NHB: Proximal | 1.059 (0.820–1.367) | 0.958 (0.885–1.037) | 0.960 (0.729–1.264) | 1.069 (0.969–1.180) |

| NHB: Rectal | 1.126 (0.855–1.482) | 0.824 (0.752–0.903) | 1.026 (0.763–1.381) | 0.856 (0.764–0.958) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hsieh, M.-C.; Stoffel, E.M.; Purrington, K.; Wu, X.-C.; Ahn, J.; Patil, S.; Wen, S.; Jawla, M.; Mabvakure, B.; Rozek, L.S. Effect of Race and Tumor Subsite on Survival Outcome in Early- and Late-Onset Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2026, 18, 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020180

Hsieh M-C, Stoffel EM, Purrington K, Wu X-C, Ahn J, Patil S, Wen S, Jawla M, Mabvakure B, Rozek LS. Effect of Race and Tumor Subsite on Survival Outcome in Early- and Late-Onset Colorectal Cancer. Cancers. 2026; 18(2):180. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020180

Chicago/Turabian StyleHsieh, Mei-Chin, Elena M. Stoffel, Kristen Purrington, Xiao-Cheng Wu, Jaeil Ahn, Siddhi Patil, Shengdi Wen, Muhammed Jawla, Batsirai Mabvakure, and Laura S. Rozek. 2026. "Effect of Race and Tumor Subsite on Survival Outcome in Early- and Late-Onset Colorectal Cancer" Cancers 18, no. 2: 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020180

APA StyleHsieh, M.-C., Stoffel, E. M., Purrington, K., Wu, X.-C., Ahn, J., Patil, S., Wen, S., Jawla, M., Mabvakure, B., & Rozek, L. S. (2026). Effect of Race and Tumor Subsite on Survival Outcome in Early- and Late-Onset Colorectal Cancer. Cancers, 18(2), 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020180