Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonist Use and Pancreatic Cancer Risk in Patients with Chronic Pancreatitis

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

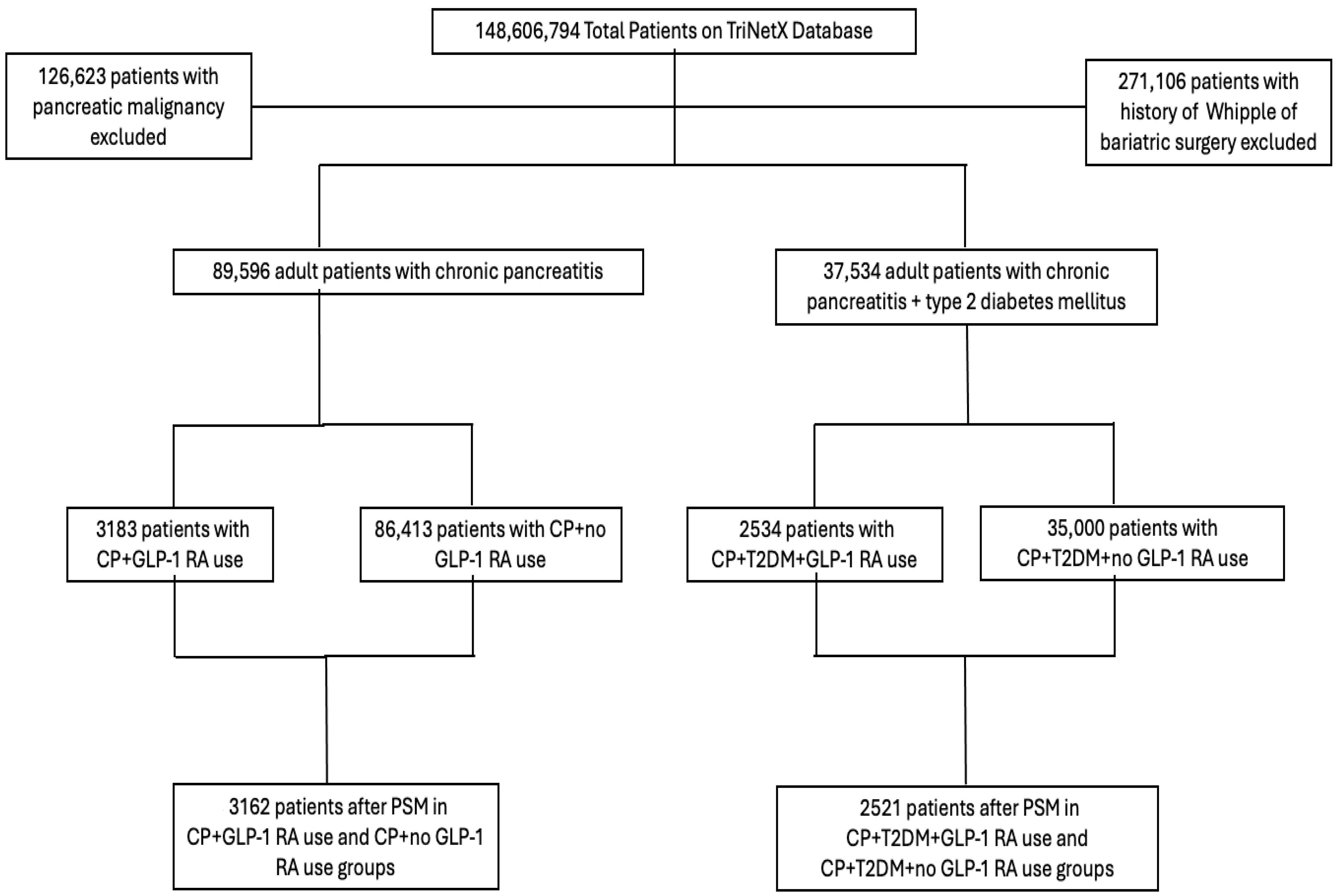

2.1. Study Design and Patient Identification

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics Before and After Matching

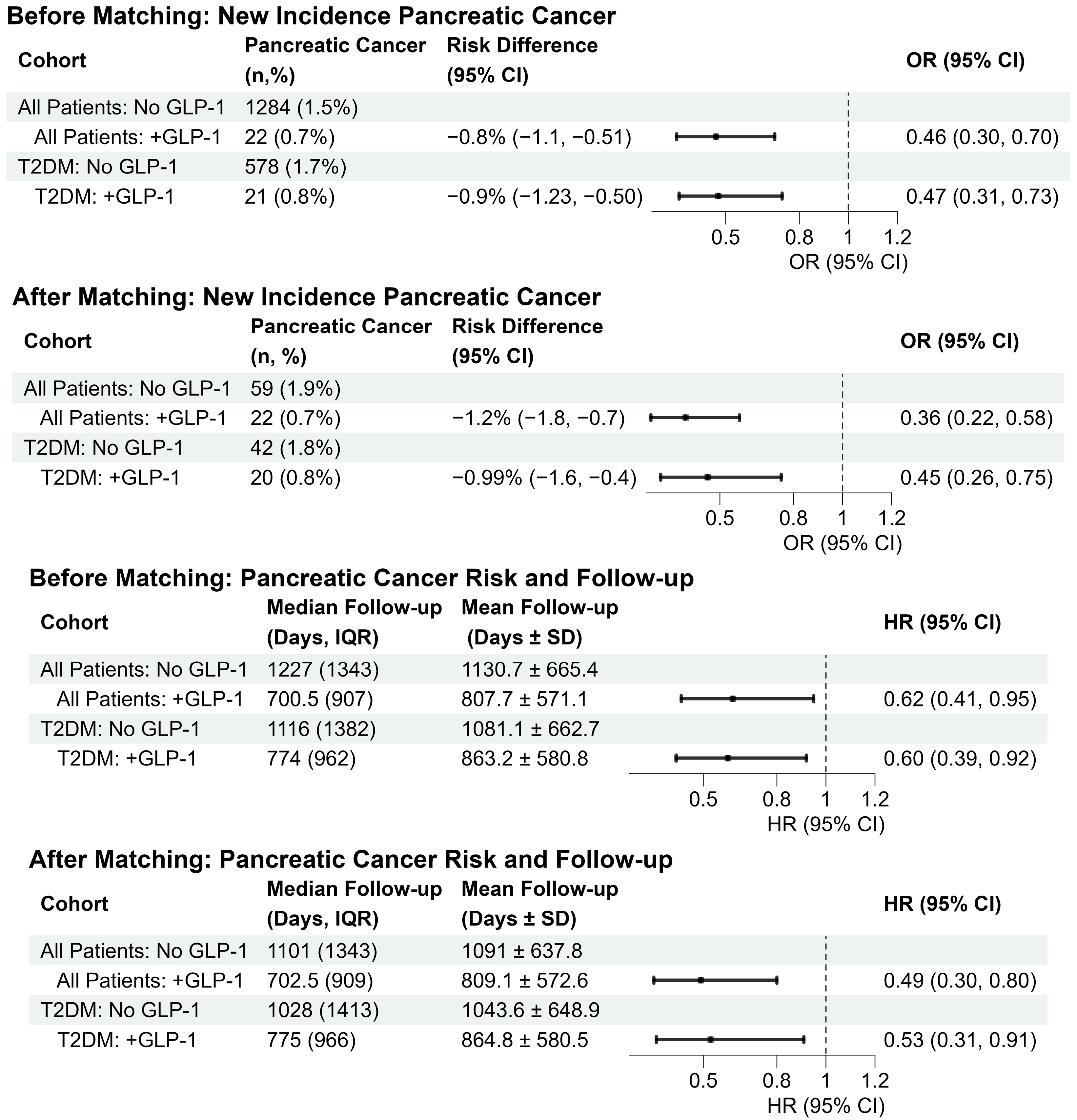

3.2. Follow-Up Time

3.3. Pancreatic Cancer Incidence in Unmatched and Matched Cohorts

3.4. Characteristics of Patients with Coexisting T2DM

3.5. Follow-Up Time in the Patients with Coexisting T2DM

3.6. Pancreatic Cancer Incidence in Patients with CP and T2DM

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lin, A.; Ding, Y.; Li, Z.; Jiang, A.; Liu, Z.; Wong, H.Z.H.; Cheng, Q.; Zhang, J.; Luo, P. Glucagon-like Peptide 1 Receptor Agonists and Cancer Risk: Advancing Precision Medicine through Mechanistic Understanding and Clinical Evidence. Biomark. Res. 2025, 13, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moiz, A.; Filion, K.B.; Tsoukas, M.A.; Yu, O.H.; Peters, T.M.; Eisenberg, M.J. Mechanisms of GLP-1 Receptor Agonist-Induced Weight Loss: A Review of Central and Peripheral Pathways in Appetite and Energy Regulation. Am. J. Med. 2025, 138, 934–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayoub, M.; Faris, C.; Juranovic, T.; Chela, H.; Daglilar, E. The Use of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Does Not Increase the Risk of Pancreatic Cancer: A U.S.-Based Cohort Study. Cancers 2024, 16, 1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryadevara, V.; Roy, A.; Sahoo, J.; Kamalanathan, S.; Naik, D.; Mohan, P.; Kalayarasan, R. Incretin Based Therapy and Pancreatic Cancer: Realising the Reality. World J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 2881–2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukhanova, M.; Wozny, J.S.; Truong, C.N. Trends in Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Receptor Agonist Prescribing Patterns. Am. J. Manag. Care. 2025, 31, e228–e234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michos, E.D.; Lopez-Jimenez, F.; Gulati, M. Role of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists in Achieving Weight Loss and Improving Cardiovascular Outcomes in People With Overweight and Obesity. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e029282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Xiang, X.; Fang, X.; Feng, S. Effects of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists on Cardiovascular Outcomes in High-Risk Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2024, 16, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filippatos, T.D.; Panagiotopoulou, T.V.; Elisaf, M.S. Adverse Effects of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists. Rev. Diabet. Stud. 2014, 11, 202–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xu, R.; Kaelber, D.C.; Berger, N.A. Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Receptor Agonists and 13 Obesity-Associated Cancers in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2421305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverii, G.A.; Marinelli, C.; Bettarini, C.; Del Vescovo, G.G.; Monami, M.; Mannucci, E. GLP-1 Receptor Agonists and the Risk for Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2025, 27, 4454–4468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Wu, T.; Khan, N.U. Association between GLP-1 Receptor Agonists as a Class and Colorectal Cancer Risk: A Meta-Analysis of Retrospective Cohort Studies. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025, 25, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dankner, R.; Murad, H.; Agay, N.; Olmer, L.; Freedman, L.S. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists and Pancreatic Cancer Risk in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, E2350408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malka, D.; Hammel, P.; Maire, F.; Rufat, P.; Madeira, I.; Pessione, F.; Lévy, P. Risk of Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma in Chronic Pancreatitis. Gut 2002, 51, 849–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Cosquer, G.; Maulat, C.; Bournet, B.; Cordelier, P.; Buscail, E.; Buscail, L. Pancreatic Cancer in Chronic Pancreatitis: Pathogenesis and Diagnostic Approach. Cancers 2023, 15, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afghani, E.; Klein, A.P. Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma: Trends in Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Outcomes. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North. Am. 2022, 36, 879–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Kandlakunta, H.; Nagpal, S.J.S.; Feng, Z.; Hoos, W.; Petersen, G.M.; Chari, S.T. Model to Determine Risk of Pancreatic Cancer in Patients with New-Onset Diabetes. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 730–739.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodarzi, M.O.; Petrov, M.S.; Andersen, D.K.; Hart, P.A. Diabetes in Chronic Pancreatitis: Risk Factors and Natural History. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2021, 37, 526–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.S.; Jun, H.S. Effects of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 on Oxidative Stress and Nrf2 Signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; She, M.; Xu, M.; Chen, H.; Li, J.; Chen, X.; Zheng, D.; Liu, J.; Chen, S.; Zhu, J.; et al. GLP-1 Treatment Protects Endothelial Cells from Oxidative Stress-Induced Autophagy and Endothelial Dysfunction. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 14, 1696–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, S.C.; Kim, J.; Kim, B.H. Use of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists Does Not Increase the Risk of Cancer in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Metab. J. 2025, 49, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Wang, W.; Pan, Q.; Guo, L. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Intersects With Pancreatic Cancer Diagnosis and Development. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 730038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.; Guo, Q.; Li, Z.; Wang, Z. Association between Different GLP-1 Receptor Agonists and Acute Pancreatitis: Case Series and Real-World Pharmacovigilance Analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1461398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Chang, H.Y.; Richards, T.M.; Weiner, J.P.; Clark, J.M.; Segal, J.B. Glucagonlike Peptide 1-Based Therapies and Risk of Hospitalization for Acute Pancreatitis in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Population-Based Matched Case-Control Study. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013, 173, 534–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, F.; Patel, Z.; Naji, M.; Kaur, N. S1849 Watch out for Semaglutide: Potential Cause of Pancreatitis? Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 117, e1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoub, M.; Chela, H.; Amin, N.; Hunter, R.; Anwar, J.; Tahan, V.; Daglilar, E. Pancreatitis Risk Associated with GLP-1 Receptor Agonists, Considered as a Single Class, in a Comorbidity-Free Subgroup of Type 2 Diabetes Patients in the United States: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Yang, S.; Zhou, Z. GLP-1 Receptor Agonists and Pancreatic Safety Concerns in Type 2 Diabetic Patients: Data from Cardiovascular Outcome Trials. Endocrine 2020, 68, 518–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Nadora, D.; Bernstein, E.; How-Volkman, C.; Truong, A.; Joy, B.; Kou, M.; Muttalib, Z.; Alam, A.; Frezza, E. Evaluating the Rates of Pancreatitis and Pancreatic Cancer Among GLP-1 Receptor Agonists: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. 2025, 8, e70113. [Google Scholar]

- Henney, A.E.; Heague, M.; Riley, D.R.; Hydes, T.J.; Anson, M.; Alam, U.; Cuthbertson, D.J. Synergistic Associations of Metformin and GLP-1 Receptor Agonist Use with Adiposity-Related Cancer Incidence in People Living with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, S.H. Anti-Inflammatory Role of Glucagon-like Peptide 1 Receptor Agonists and Its Clinical Implications. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 15, 20420188231222367. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z.; Zong, Y.; Ma, Y.; Tian, Y.; Pang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Gao, J. Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor: Mechanisms and Advances in Therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Before Matching | After Matching | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic Name | No GLP-1 1 | +GLP-1 1 | SMD 2 | No GLP-1 1 | +GLP-1 1 | SMD 2 |

| n | 86,413 | 3183 | 3162 | 3162 | ||

| Age at Index | 54.58 ± 15.38 | 57.28 ± 12.79 | 0.19 *** | 57.7 ± 13.85 | 57.27 ± 12.79 | 0.03 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 46,261 (53.5%) | 1531 (48.1%) | 0.11 *** | 1469 (46.5%) | 1527 (48.3%) | 0.04 |

| Female | 40,133 (46.4%) | 1652 (51.9%) | 0.11 *** | 1693 (53.5%) | 1635 (51.7%) | 0.04 |

| Race | ||||||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 574 (0.7%) | 29 (0.9%) | 0.03 | 25 (0.8%) | 29 (0.9%) | 0.01 |

| Asian | 2609 (3%) | 103 (3.2%) | 0.01 | 107 (3.4%) | 103 (3.3%) | 0.01 |

| Black or African American | 14,618 (16.9%) | 550 (17.3%) | 0.01 | 557 (17.6%) | 547 (17.3%) | 0.01 |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 327 (0.4%) | 18 (0.6%) | 0.03 | 18 (0.6%) | 18 (0.6%) | 0.00 |

| Other Race | 2550 (3%) | 144 (4.5%) | 0.08 *** | 122 (3.9%) | 141 (4.5%) | 0.03 |

| Unknown Race | 6519 (7.5%) | 160 (5%) | 0.10 *** | 135 (4.3%) | 159 (5%) | 0.04 |

| White | 59,216 (68.5%) | 2179 (68.5%) | 0.00 | 2198 (69.5%) | 2165 (68.5%) | 0.02 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 5150 (6%) | 285 (9%) | 0.11 *** | 274 (8.7%) | 282 (8.9%) | 0.01 |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 63,795 (73.8%) | 2440 (76.7%) | 0.07 *** | 2443 (77.3%) | 2423 (76.6%) | 0.02 |

| Unknown Ethnicity | 17,468 (20.2%) | 458 (14.4%) | 0.15 *** | 445 (14.1%) | 457 (14.5%) | 0.01 |

| Labs | ||||||

| BMI (mean) 3 | 26.36 ± 6.49 | 33.26 ± 7.73 | 0.97 *** | 31.11 ± 7.12 | 33.26 ± 7.73 | 0.29 *** |

| BMI ≥ 30 | 24,102 (27.9%) | 2215 (69.6%) | 0.92 *** | 2277 (72%) | 2194 (69.4%) | 0.06 * |

| Hemoglobin A1c (mean) 4 | 6.8 ± 2.14 | 8.09 ± 2.23 | 0.59 *** | 8.08 ± 2.3 | 8.08 ± 2.23 | 0.00 |

| Hemoglobin A1c ≥ 8 | 10,059 (11.6%) | 1782 (56%) | 1.06 *** | 1771 (56%) | 1761 (55.7%) | 0.01 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Alcohol-related disorders | 21,490 (24.9%) | 681 (21.4%) | 0.08 *** | 632 (20%) | 675 (21.3%) | 0.03 |

| Cyst of pancreas | 10,451 (12.1%) | 590 (18.5%) | 0.18 *** | 564 (17.8%) | 580 (18.3%) | 0.01 |

| Hypertension | 45,345 (52.5%) | 2642 (83%) | 0.69 *** | 2686 (84.9%) | 2622 (82.9%) | 0.06 * |

| Hyperlipidemia | 27,192 (31.5%) | 2202 (69.2%) | 0.81 *** | 2248 (71.1%) | 2185 (69.1%) | 0.04 |

| Overweight/obesity | 14,044 (16.3%) | 2010 (63.1%) | 1.09 *** | 2104 (66.5%) | 1989 (62.9%) | 0.08 ** |

| Tobacco use | 7950 (9.2%) | 499 (15.7%) | 0.20 *** | 474 (15%) | 491 (15.5%) | 0.01 |

| Type 2 Diabetes | 27,683 (32%) | 2682 (84.3%) | 1.25 *** | 2586 (81.8%) | 2661 (84.2%) | 0.06 * |

| Medications | ||||||

| Insulin | 23,568 (27.3%) | 2260 (71%) | 0.97 *** | 2319 (73.3%) | 2239 (70.8%) | 0.06 * |

| Metformin | 10,154 (11.8%) | 1983 (62.3%) | 1.23 *** | 1944 (61.5%) | 1962 (62%) | 0.01 |

| SGLT2 inhibitors | 1945 (2.3%) | 924 (29%) | 0.79 *** | 743 (23.5%) | 903 (28.6%) | 0.12 *** |

| GLP-1 RA Medications | ||||||

| Albiglutide | 0 (0%) | 10 (0.3%) | NA | 0 (0%) | 10 (0.3%) | NA |

| Dulaglutide | 0 (0%) | 844 (26.5%) | NA | 0 (0%) | 836 (26.4%) | NA |

| Exenatide | 0 (0%) | 58 (1.8%) | NA | 0 (0%) | 58 (1.8%) | NA |

| Liraglutide | 0 (0%) | 332 (10.4%) | NA | 0 (0%) | 331 (10.5%) | NA |

| Lixisenatide | 0 (0%) | 38 (1.2%) | NA | 0 (0%) | 38 (1.2%) | NA |

| Semaglutide | 0 (0%) | 1469 (46.2%) | NA | 0 (0%) | 1461 (46.2%) | NA |

| Tirzepatide | 0 (0%) | 459 (14.4%) | NA | 0 (0%) | 455 (14.4%) | NA |

| Before Matching | After Matching | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No GLP-1 1 | +GLP-1 1 | SMD 2 | No GLP-1 1 | +GLP-1 1 | SMD 2 | |

| n | 35,000 | 2534 | 2521 | 2521 | ||

| Age at Index | 57.25 ± 14.35 | 58.09 ± 12.57 | 0.06 ** | 58.59 ± 13.49 | 58.09 ± 12.56 | 0.04 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 20,559 (58.7%) | 1339 (52.8%) | 0.12 *** | 1314 (52.1%) | 1335 (53%) | 0.02 |

| Female | 14,435 (41.2%) | 1195 (47.2%) | 0.12 *** | 1207 (47.9%) | 1186 (47%) | 0.02 |

| Race | ||||||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 289 (0.8%) | 24 (0.9%) | 0.01 | 17 (0.7%) | 24 (1%) | 0.03 |

| Asian | 1240 (3.5%) | 93 (3.7%) | 0.01 | 95 (3.8%) | 93 (3.7%) | 0.00 |

| Black or African American | 7292 (20.8%) | 491 (19.4%) | 0.04 | 504 (20%) | 490 (19.4%) | 0.01 |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 173 (0.5%) | 17 (0.7%) | 0.02 | 16 (0.6%) | 17 (0.7%) | 0.00 |

| Other Race | 1031 (2.9%) | 115 (4.5%) | 0.08 *** | 100 (4%) | 109 (4.3%) | 0.02 |

| Unknown Race | 2454 (7%) | 143 (5.6%) | 0.06 ** | 129 (5.1%) | 143 (5.7%) | 0.02 |

| White | 22,521 (64.3%) | 1651 (65.2%) | 0.02 | 1660 (65.8%) | 1645 (65.3%) | 0.01 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 2504 (7.2%) | 247 (9.7%) | 0.09 *** | 247 (9.8%) | 243 (9.6%) | 0.01 |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 26,102 (74.6%) | 1908 (75.3%) | 0.02 | 1905 (75.6%) | 1900 (75.4%) | 0.00 |

| Unknown Ethnicity | 6394 (18.3%) | 379 (15%) | 0.09 *** | 369 (14.6%) | 378 (15%) | 0.01 |

| Labs | ||||||

| BMI 3 | 27.36 ± 6.98 | 32.73 ± 7.74 | 0.73 *** | 30.4 ± 7.18 | 32.71 ± 7.73 | 0.31 *** |

| BMI ≥ 30 | 13,318 (38.1%) | 1711 (67.5%) | 0.62 *** | 1700 (67.4%) | 1698 (67.4%) | 0.00 |

| Hemoglobin A1c 4 | 7.75 ± 2.33 | 8.5 ± 2.13 | 0.33 *** | 8.37 ± 2.25 | 8.5 ± 2.14 | 0.06 |

| Hemoglobin A1c ≥ 8 | 11,158 (31.9%) | 1722 (68%) | 0.77 *** | 1731 (68.7%) | 1709 (67.8%) | 0.02 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Alcohol-related disorders | 9177 (26.2%) | 561 (22.1%) | 0.10 *** | 539 (21.4%) | 558 (22.1%) | 0.02 |

| Cyst of pancreas | 5333 (15.2%) | 460 (18.2%) | 0.08 *** | 444 (17.6%) | 451 (17.9%) | 0.01 |

| Hypertension | 25,544 (73%) | 2218 (87.5%) | 0.37 *** | 2233 (88.6%) | 2205 (87.5%) | 0.03 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 17,381 (49.7%) | 1892 (74.7%) | 0.53 *** | 1956 (77.6%) | 1879 (74.5%) | 0.07 * |

| Overweight/obesity (E66) | 9136 (26.1%) | 1543 (60.9%) | 0.75 *** | 1531 (60.7%) | 1530 (60.7%) | 0.00 |

| Tobacco use | 3986 (11.4%) | 424 (16.7%) | 0.15 *** | 405 (16.1%) | 421 (16.7%) | 0.02 |

| Medications | ||||||

| Insulin | 21,798 (62.3%) | 2053 (81%) | 0.43 *** | 2074 (82.3%) | 2042 (81%) | 0.03 |

| Metformin | 10,968 (31.3%) | 1802 (71.1%) | 0.87 *** | 1830 (72.6%) | 1789 (71%) | 0.04 |

| SGLT2 inhibitors | 1969 (5.6%) | 865 (34.1%) | 0.76 *** | 788 (31.3%) | 852 (33.8%) | 0.05 |

| GLP-1 RA Medications | ||||||

| Albiglutide | 0 (0%) | 10 (0.4%) | NA | 0 (0%) | 10 (0.4%) | NA |

| Dulaglutide | 0 (0%) | 786 (31%) | NA | 0 (0%) | 782 (31%) | NA |

| Exenatide | 0 (0%) | 50 (2%) | NA | 0 (0%) | 50 (2%) | NA |

| Liraglutide | 0 (0%) | 278 (11%) | NA | 0 (0%) | 277 (11%) | NA |

| Lixisenatide | 0 (0%) | 33 (1.3%) | NA | 0 (0%) | 33 (1.3%) | NA |

| Semaglutide | 0 (0%) | 1119 (44.2%) | NA | 0 (0%) | 1113 (44.1%) | NA |

| Tirzepatide | 0 (0%) | 283 (11.2%) | NA | 0 (0%) | 281 (11.1%) | NA |

| Before Matching | After Matching | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Follow-Up (Days ± SD) | Median Follow-Up Days (IQR) | HR (95% CI) | p-Value | Mean Follow-Up (Days + SD) | Median Follow-Up Days (IQR) | HR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| All Patients | ||||||||

| No GLP-1 vs. +GLP-1 | 1130.7 ± 665.4 | 1227 (1343) | 1091 ± 637.8 | 1101 (1343) | ||||

| 807.7 ± 571.1 | 700.5 (907) | 0.62 (0.41, 0.95) | 0.03 | 809.1 ± 572.6 | 702.5 (909) | 0.49 (0.30, 0.80) | 0.003 | |

| Type 2 Diabetic Patients | ||||||||

| No GLP-1 vs. + GLP-1 | 1081.1 ± 662.7 | 1116 (1382) | 1043.6 ± 648.9 | 1028 (1413) | ||||

| 863.2 ± 580.8 | 774 (962) | 0.60 (0.39, 0.92) | 0.02 | 864.8 ± 580.5 | 775 (966) | 0.53 (0.31, 0.91) | 0.02 | |

| Before Matching | After Matching | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | Risk Difference (95% CI) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value | n (%) | Risk Difference (95% CI) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| All Patients | ||||||||

| No GLP-1 vs. +GLP-1 | 1284 (1.5%) | 59 (1.9) | ||||||

| 22 (0.7%) | −0.8% (−1.1, −0.51) | 0.46 (0.30, 0.70) | <0.001 | 22 (0.7) | −1.24% (−1.81, −0.67) | 0.36 (0.22, 0.58) | <0.001 | |

| Type 2 Diabetic Patients | ||||||||

| No GLP-1 vs. +GLP-1 | 578 (1.7%) | 42 (1.8%) | ||||||

| 21 (0.8%) | −0.87% (−1.23, −0.50) | 0.47 (0.31, 0.73) | <0.001 | 20 (0.8%) | −0.99% (−1.6, −0.36) | 0.44 (0.26, 0.75) | 0.002 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ailawadi, S.; Murphy, J.E.; Storandt, M.H.; Mahipal, A. Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonist Use and Pancreatic Cancer Risk in Patients with Chronic Pancreatitis. Cancers 2026, 18, 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020179

Ailawadi S, Murphy JE, Storandt MH, Mahipal A. Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonist Use and Pancreatic Cancer Risk in Patients with Chronic Pancreatitis. Cancers. 2026; 18(2):179. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020179

Chicago/Turabian StyleAilawadi, Sarina, Jennifer E. Murphy, Michael H. Storandt, and Amit Mahipal. 2026. "Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonist Use and Pancreatic Cancer Risk in Patients with Chronic Pancreatitis" Cancers 18, no. 2: 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020179

APA StyleAilawadi, S., Murphy, J. E., Storandt, M. H., & Mahipal, A. (2026). Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonist Use and Pancreatic Cancer Risk in Patients with Chronic Pancreatitis. Cancers, 18(2), 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020179