Role of Gut Microbiome in Oncogenesis and Oncotherapies

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Selection and Narrative Synthesis

1.2. Review of Oncogenesis and Oncotherapies

2. Gastrointestinal Cancers

2.1. Colorectal Cancer

2.1.1. Microbiome in Oncogenesis

2.1.2. Microbiome in Therapy Response

2.2. Gastric Cancer

2.2.1. Microbiome in Oncogenesis

2.2.2. Microbiome in Therapy Response

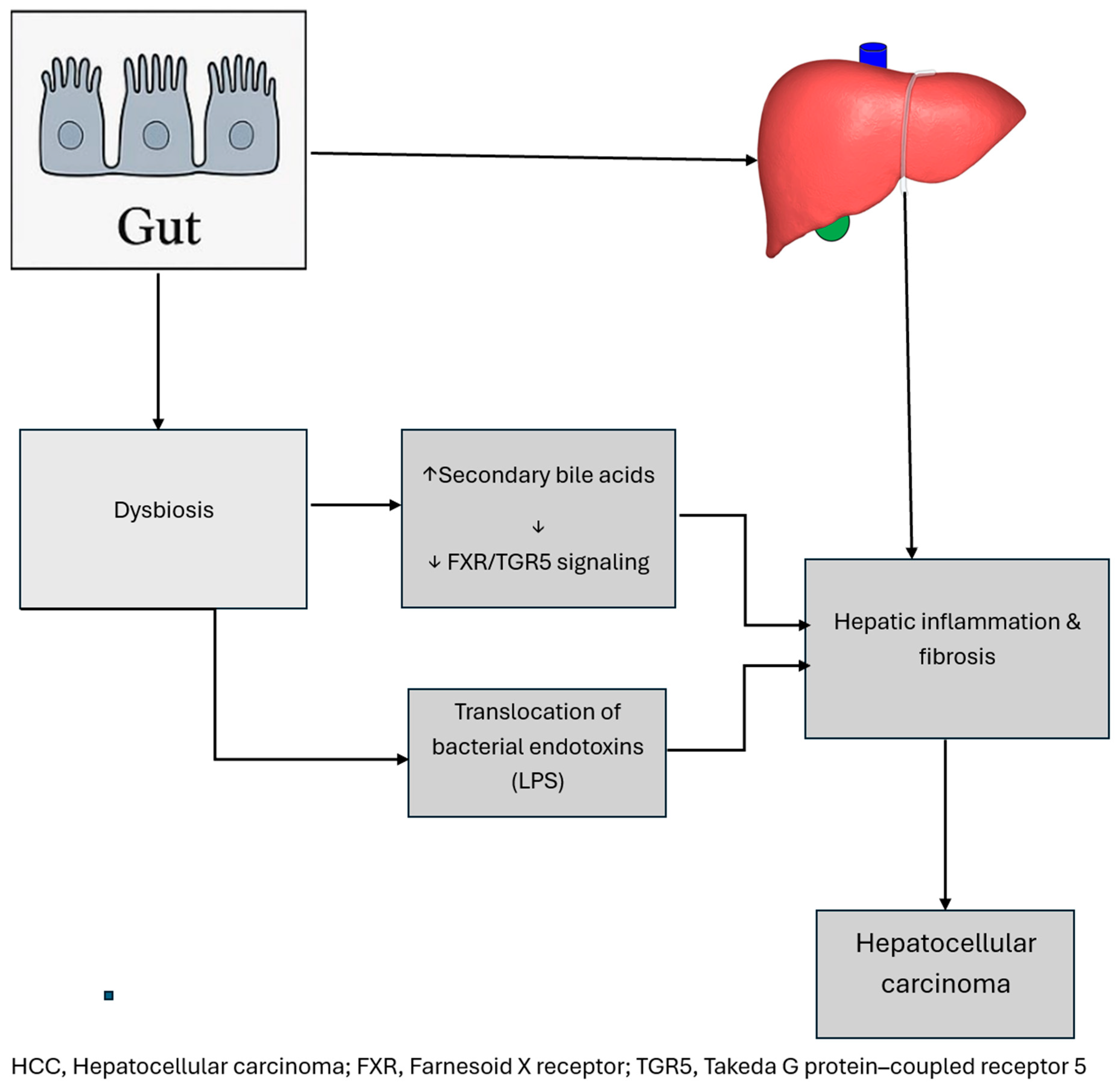

2.3. Hepatocellular Carcinoma

2.3.1. Microbiome in Oncogenesis

2.3.2. Microbiome in Therapy Response

2.4. Gallbladder Cancer

2.4.1. Microbiome in Oncogenesis

2.4.2. Microbiome in Therapy Response

2.5. Esophageal Cancer

2.5.1. Microbiome in Oncogenesis

2.5.2. Microbiome in Therapy Response

2.6. Pancreatic Cancer

2.6.1. Microbiome in Oncogenesis

2.6.2. Microbiome in Therapy Response

3. Extra-Gastrointestinal Cancers

3.1. Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma

3.1.1. Microbiome in Oncogenesis

3.1.2. Microbiome in Therapy Response

3.2. Cervical Cancer

3.2.1. Microbiome in Oncogenesis

3.2.2. Microbiome in Therapy Response

3.3. Prostate Cancer

3.3.1. Microbiome in Oncogenesis

3.3.2. Microbiome in Therapy Response

3.4. Melanoma

3.4.1. Microbiome in Oncogenesis

3.4.2. Microbiome in Therapy Response

3.5. Brain Tumor

3.5.1. Microbiome in Oncogenesis

3.5.2. Microbiome in Therapy Response

3.6. Breast Cancer

3.6.1. Microbiome in Oncogenesis

3.6.2. Microbiome in Therapy Response

3.7. Lung Cancer

3.7.1. Microbiome in Oncogenesis

3.7.2. Microbiome in Oncotherapy Response

4. Discussion

4.1. Common Mechanistic Themes Across Cancers

4.2. Unique Microbiome–Cancer Axes

4.3. Clinical Translation and Therapeutic Implications

4.4. Microbiome as a Biomarker

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pires, L.; González-Paramás, A.M.; Heleno, S.A.; Calhelha, R.C. The Role of Gut Microbiota in the Etiopathogenesis of Multiple Chronic Diseases. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takiishi, T.; Fenero, C.I.M.; Câmara, N.O.S. Intestinal barrier and gut microbiota: Shaping our immune responses throughout life. Tissue Barriers 2017, 5, e1373208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, S.V.; Pedersen, O. The Human Intestinal Microbiome in Health and Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 2369–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmink, B.A.; Khan, M.A.W.; Hermann, A.; Gopalakrishnan, V.; Wargo, J.A. The microbiome, cancer, and cancer therapy. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effendi, R.M.R.A.; Anshory, M.; Kalim, H.; Dwiyana, R.F.; Suwarsa, O.; Pardo, L.M.; Nijsten, T.E.C.; Thio, H.B. Akkermansia muciniphila and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in Immune-Related Diseases. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGruttola, A.K.; Low, D.; Mizoguchi, A.; Mizoguchi, E. Current Understanding of Dysbiosis in Disease in Human and Anima Models. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2016, 22, 1137–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; An, Y.; Qin, X.; Wu, X.; Wang, X.; Hou, H.; Song, X.; Liu, T.; Wang, B.; Huang, X.; et al. Gut Microbiota-Derived Metabolites in Colorectal Cancer: The Bad and the Challenges. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 739648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, F.M.; Liu, H.L. Fusobacterium nucleatum and colorectal cancer: A review. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2018, 10, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correa, P.; Piazuelo, M.B. Helicobacter pylori Infection and Gastric Adenocarcinoma. US Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Rev. 2011, 7, 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, W.; Guo, S.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wang, M.; Sang, L.; Chang, B.; Wang, B. Hepatocellular Carcinoma: How the Gut Microbiota Contributes to Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Therapy. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 873160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Zhang, Q. Gut microbiota influences the efficiency of immune checkpoint inhibitors by modulating the immune system (Review). Oncol. Lett. 2024, 27, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, Y.; Baines, K.J.; Vareki, S.M. Microbiome bacterial influencers of host immunity and response to immunotherapy. Cell Rep. Med. 2024, 5, 101487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, K.; Shi, C.; Li, G. Cancer Immunotherapy: Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Brings Light. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2022, 23, 1777–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Baba, Y.; Ishimoto, T.; Gu, X.; Zhang, J.; Nomoto, D.; Okadome, K.; Baba, H.; Qiu, P. Gut microbiome in gastrointestinal cancer: A friend or foe? Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 4101–4117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, M.; Li, X.; Lau, H.C.-H.; Yu, J. The gut microbiota in cancer immunity and immunotherapy. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2025, 22, 1012–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Q.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, Z.; Xie, T.; Sui, X. Harnessing phytochemicals: Innovative strategies to enhance cancer immunotherapy. Drug Resist. Updates 2025, 79, 101206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.M.; Sears, C.L. The Role of the Gut Microbiome in Cancer: A Review, with Special Focus on Colorectal Neoplasia and Clostridioides difficile. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 77, S471–S478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W. Linking microbiome to cancer: A mini-review on contemporary advances. Microbe 2025, 6, 1000279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, D.; Huang, D.; Zhao, Y.; Hu, W.; Lin, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Zeng, J.; et al. Elucidating the genotoxicity of Fusobacterium nucleatum-secreted mutagens in colorectal cancer carcinogenesis. Gut Pathog. 2024, 16, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiman, L.; Moazzam, K.; Anjum, S.; Kausar, H.; Sharif, E.A.M.; Ibrahim, W.N. Gut dysbiosis in cancer immunotherapy: Microbiota-mediated resistance and emerging treatments. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1575452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, M.R.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Hao, Y.; Cai, G.; Han, Y.W. Fusobacterium nucleatum Promotes Colorectal Carcinogenesis by Modulating E-Cadherin/β-Catenin Signaling via its FadA Adhesin. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 14, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Luo, H.; Gao, F.; Tang, Q.; Chen, W. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes the progression of colorectal cancer by interacting with E-cadherin. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 16, 2606–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.T.; Kantilal, H.K.; Davamani, F. The Mechanism of Bacteroides fragilis Toxin Contributes to Colon Cancer Formation. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 27, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salesse, L.; Lucas, C.; Hoang, M.H.T.; Sauvanet, P.; Rezard, A.; Rosenstiel, P.; Damon-Soubeyrand, C.; Barnich, N.; Godfraind, C.; Dalmasso, G.; et al. Colibactin-Producing Escherichia coli Induce the Formation of Invasive Carcinomas in a Chronic Inflammation-Associated Mouse Model. Cancers 2021, 13, 2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pleguezuelos-Manzano, C.; Puschhof, J.; Rosendahl Huber, A.; Van Hoeck, A.; Wood, H.M.; Nomburg, J.; Gurjao, C.; Manders, F.; Dalmasso, G.; Stege, P.B.; et al. Mutational signature in colorectal cancer caused by genotoxic pks+ E. coli. Nature 2020, 580, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, P.; Hold, G.L.; Flint, H.J. The gut microbiota, bacterial metabolites and colorectal cancer. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 12, 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Wei, Z.; Wang, Z.; Xu, F.; Yang, J.; Lin, B.; Chen, Y.; Wenren, H.; Wu, L.; Guo, X.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum induces oxaliplatin resistance by inhibiting ferroptosis through E-cadherin/β-catenin/GPX4 axis in colorectal cancer. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 220, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yang, Y.; Weng, W.; Guo, B.; Cai, G.; Ma, Y.; Cai, S. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes chemoresistance to 5-fluorouracil by upregulation of BIRC3 expression in colorectal cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routy, B.; le Chatelier, E.; DeRosa, L.; Duong, C.P.M.; Alou, M.T.; Daillère, R.; Fluckiger, A.; Messaoudene, M.; Rauber, C.; Roberti, M.P.; et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1–based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science 2018, 359, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruch, E.N.; Youngster, I.; Ben-Betzalel, G.; Ortenberg, R.; Lahat, A.; Katz, L.; Adler, K.; Dick-Necula, D.; Raskin, S.; Bloch, N.; et al. Fecal microbiota transplant promotes response in immunotherapy-refractory melanoma patients. Science 2020, 371, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palframan, S.L.; Kwok, T.; Gabriel, K. Vacuolating cytotoxin A (VacA), a key toxin for Helicobacter pylori pathogenesis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2012, 2, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coker, O.O.; Dai, Z.; Nie, Y.; Zhao, G.; Cao, L.; Nakatsu, G.; Wu, W.K.; Wong, S.H.; Chen, Z.; Sung, J.J.Y.; et al. Mucosal microbiome dysbiosis in gastric carcinogenesis. Gut 2017, 67, 1024–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Lau, H.C.-H.; Peppelenbosch, M.; Yu, J. Gastric Microbiota beyond H. pylori: An Emerging Critical Character in Gastric Carcinogenesis. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogiatzi, P.; Cassone, M.; Luzzi, I.; Lucchetti, C.; Otvos, L.; Giordano, A. Helicobacter pylori as a class I carcinogen: Physiopathology and management strategies. J. Cell. Biochem. 2007, 102, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eun, C.S.; Kim, B.K.; Han, D.S.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, K.M.; Choi, B.Y.; Song, K.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, J.F. Differences in Gastric Mucosal Microbiota Profiling in Patients with Chronic Gastritis, Intestinal Metaplasia, and Gastric Cancer Using Pyrosequencing Methods. Helicobacter 2014, 19, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polk, D.B.; Peek, R.M., Jr. Helicobacter pylori: Gastric cancer and beyond. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2010, 10, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manothiya, P.; Dash, D.; Koiri, R.K. Gut microbiota dysbiosis and the gut–liver–brain axis: Mechanistic insights into hepatic encephalopathy. Med. Microecol. 2025, 26, 100157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzaniga, F.S.; Kasper, D.L. The gut microbiome and cancer response to immune checkpoint inhibitors. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 135, e184321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciorba, M.A.; Hallemeier, C.L.; Stenson, W.F.; Parikh, P.J. Probiotics to prevent gastrointestinal toxicity from cancer therapy: An interpretive review and call to action. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 2015, 9, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Han, M.; Heinrich, B.; Fu, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Sandhu, M.; Agdashian, D.; Terabe, M.; Berzofsky, J.A.; Fako, V.; et al. Gut microbiome–mediated bile acid metabolism regulates liver cancer via NKT cells. Science 2018, 360, eaan5931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, N.; Yang, F.; Li, A.; Prifti, E.; Chen, Y.; Shao, L.; Guo, J.; Le Chatelier, E.; Yao, J.; Wu, L.; et al. Alterations of the human gut microbiome in liver cirrhosis. Nature 2014, 513, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, T.; Tu, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Tan, D.; Jiang, W.; Cai, S.; Zhao, P.; Song, R.; et al. Gut microbiome affects the response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, I.; Ahad, H.; Said, A. Gut microbiome in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease associated hepatocellular carcinoma: Current knowledge and potential for therapeutics. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2022, 14, 947–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dapito, D.H.; Mencin, A.; Gwak, G.-Y.; Pradere, J.-P.; Jang, M.-K.; Mederacke, I.; Caviglia, J.M.; Khiabanian, H.; Adeyemi, A.; Bataller, R.; et al. Promotion of Hepatocellular Carcinoma by the Intestinal Microbiota and TLR4. Cancer Cell 2012, 21, 504–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Zheng, R.-D.; Sun, X.-Q.; Ding, W.-J.; Wang, X.-Y.; Fan, J.-G. Gut microbiota dysbiosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 2017, 16, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinato, D.J.; Gramenitskaya, D.; Altmann, D.M.; Boyton, R.J.; Mullish, B.H.; Marchesi, J.R.; Bower, M. Antibiotic therapy and outcome from immune-checkpoint inhibitors. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staley, C.; Weingarden, A.R.; Khoruts, A.; Sadowsky, M.J. Interaction of gut microbiota with bile acid metabolism and its influence on disease states. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S. Oral microbiota and biliary tract cancers: Unveiling hidden mechanistic links. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1585923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Dong, C.; Lin, Y.; Shi, H.; Zhou, W. Interplay between the Human Microbiome and Biliary Tract Cancer: Implications for Pathogenesis and Therapy. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saab, M.; Mestivier, D.; Sohrabi, M.; Rodriguez, C.; Khonsari, M.R.; Faraji, A.; Sobhani, I. Characterization of biliary microbiota dysbiosis in extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinero, N.; Ruiz, L.; Milani, C.; Gutiérrez-Díaz, I.; Sánchez, B.; Mangifesta, M.; Segura, J.; Cambero, I.; Campelo, A.B.; García-Bernardo, C.M.; et al. The human gallbladder microbiome is related to the physiological state and the biliary metabolic profile. Microbiome 2019, 7, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vestby, L.K.; Grønseth, T.; Simm, R.; Nesse, L.L. Bacterial Biofilm and its Role in the Pathogenesis of Disease. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafe, A.N.; Büsselberg, D. Microbiome Integrity Enhances the Efficacy and Safety of Anticancer Drug. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javanmard, A.; Ashtari, S.; Sabet, B.; Davoodi, S.H.; Rostami-Nejad, M.; Akbari, M.E.; Niaz, A.; Mortazavian, A.M. Probiotics and their role in gastrointestinal cancers prevention and treatment; an overview. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench 2018, 11, 284–295. [Google Scholar]

- Snider, E.J.; Freedberg, D.E.; Abrams, J.A. Potential Role of the Microbiome in Barrett’s Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2016, 61, 2217–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Fang, J.-Y. Fusobacterium nucleatum, a key pathogenic factor and microbial biomarker for colorectal cancer. Trends Microbiol. 2022, 31, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A.R.; Goldenring, J.R. Injury, repair, inflammation and metaplasia in the stomach. J. Physiol. 2018, 596, 3861–3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wei, B.; Xue, X.; Li, H.; Li, J. Microbiome changes in esophageal cancer: Implications for pathogenesis and prognosis. Cancer Biol. Med. 2023, 21, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Guo, L.; Liu, J.-J.; Zhao, H.-P.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.-H. Alteration of the esophageal microbiota in Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 2149–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, R.J.; Fitzsimonds, Z.R.; Wang, H.; Gao, S. Role of Porphyromonas gingivalis in oral and orodigestive squamous cell carcinoma. Periodontol. 2000 2022, 89, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadgar, N.; Keshava, V.E.; Raj, M.S.; Wagner, P.L. The Influence of the Microbiome on Immunotherapy for Gastroesophageal Cancer. Cancers 2023, 15, 4426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonneau, M.; Elkrief, A.; Pasquier, D.; Del Socorro, T.P.; Chamaillard, M.; Bahig, H.; Routy, B. The role of the gut microbiome on radiation therapy efficacy and gastrointestinal complications: A systematic review. Radiother. Oncol. 2021, 156, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Li, F.; Gao, Y.; Kang, S.; Li, J.; Guo, J. Microbiome in radiotherapy: An emerging approach to enhance treatment efficacy and reduce tissue injury. Mol. Med. 2024, 30, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Zhang, D.; Li, Z.; Jiang, H.; Li, J.; Ren, R.; Gao, X.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, W.; et al. The fecal microbiota of patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and autoimmune pancreatitis characterized by metagenomic sequencing. J. Transl. Med. 2021, 19, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, N.; Farinella, R.; Belluomini, F.; Fajkic, A.; Rizzato, C.; Souček, P.; Campa, D.; Hughes, D.J. The relationship of the microbiome, associated metabolites and the gut barrier with pancreatic cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2025, 112, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiss, B.; Mikó, E.; Sebő, É.; Toth, J.; Ujlaki, G.; Szabó, J.; Uray, K.; Bai, P.; Árkosy, P. Oncobiosis and Microbial Metabolite Signaling in Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Cancers 2020, 12, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirji, G.; Worth, A.; Bhat, S.A.; El Sayed, M.; Kannan, T.; Goldman, A.R.; Tang, H.-Y.; Liu, Q.; Auslander, N.; Dang, C.V.; et al. The microbiome-derived metabolite TMAO drives immune activation and boosts responses to immune checkpoint blockade in pancreatic cancer. Sci. Immunol. 2022, 7, eabn0704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tintelnot, J.; Xu, Y.; Lesker, T.R.; Schönlein, M.; Konczalla, L.; Giannou, A.D.; Pelczar, P.; Kylies, D.; Puelles, V.G.; Bielecka, A.A.; et al. Microbiota-derived 3-IAA influences chemotherapy efficacy in pancreatic cancer. Nature 2023, 615, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushalkar, S.; Hundeyin, M.; Daley, D.; Zambirinis, C.P.; Kurz, E.; Mishra, A.; Mohan, N.; Aykut, B.; Usyk, M.; Torres, L.E.; et al. The Pancreatic Cancer Microbiome Promotes Oncogenesis by Induction of Innate and Adaptive Immune Suppression. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castilhos, J.; Tillmanns, K.; Blessing, J.; Laraño, A.; Borisov, V.; Stein-Thoeringer, C.K. Microbiome and pancreatic cancer: Time to think about chemotherapy. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2374596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, G.; Kim, S.; Cho, B.; Kim, S.Y.; Do, E.J.; Bae, D.J.; Kim, S.; Kweon, M.N.; Song, J.S.; et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation improves anti-PD-1 inhibitor efficacy in unresectable or metastatic solid cancers refractory to anti-PD-1 inhibitor. Cell Host Microbe 2024, 32, 1380–1393.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qadami, G.H.; Secombe, K.R.; Subramaniam, C.B.; Wardill, H.R.; Bowen, J.M. Gut Microbiota-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids: Impact on Cancer Treatment Response and Toxicities. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallimidi, A.B.; Fischman, S.; Revach, B.; Bulvik, R.; Maliutina, A.; Rubinstein, A.M.; Nussbaum, G.; Elkin, M. Periodontal pathogens Porphyromonas gingivalis and Fusobacterium nucleatum promote tumor progression in an oral-specific chemical carcinogenesis model. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 22613–22623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talapko, J.; Meštrović, T.; Dmitrović, B.; Juzbašić, M.; Matijević, T.; Bekić, S.; Erić, S.; Flam, J.; Belić, D.; Erić, A.P.; et al. A Putative Role of Candida albicans in Promoting Cancer Development: A Current State of Evidence and Proposed Mechanisms. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-F.; Lu, M.-S.; Hsieh, C.-C.; Chen, W.-C. Porphyromonas gingivalis promotes tumor progression in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cell. Oncol. 2020, 44, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duizer, C.; Salomons, M.; van Gogh, M.; Gräve, S.; Schaafsma, F.A.; Stok, M.J.; Sijbranda, M.; Sivasamy, R.K.; Willems, R.J.L.; de Zoete, M.R. Fusobacterium nucleatum upregulates the immune inhibitory receptor PD-L1 in colorectal cancer cells via the activation of ALPK1. Gut Microbes 2025, 17, 2458203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Yang, R.; Sheng, Y.; Ullah, S.; Zhao, Y.; Shunjiayi, H.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Q. Insights into the oral microbiota in human systemic cancers. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1369834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forné, Á.F.; Anaya, M.J.G.; Guillot, S.J.S.; Andrade, I.P.; Fernández, L.d.l.P.; Ocón, M.J.L.; Pérez, Y.L.; Queipo-Ortuño, M.I.; Gómez-Millán, J. Influence of the microbiome on radiotherapy-inudced oral mucositis and its management: A comprehensive review. Oral Oncol. 2023, 144, 106488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minervini, G.; Franco, R.; Marrapodi, M.M.; Fiorillo, L.; Badnjević, A.; Cervino, G.; Cicciù, M. Probiotics in the Treatment of Radiotherapy-Induced Oral Mucositis: Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciernikova, S.; Sevcikova, A.; Novisedlakova, M.; Mego, M. Insights into the Relationship Between the Gut Microbiome and Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Solid Tumors. Cancers 2024, 16, 4271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pai, H.D.; Baid, R.; Palshetkar, N.P.; Pai, R.; Pai, A.; Palshetkar, R. Role of Vaginal and Gut Microbiota in Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Progression and Cervical Cancer: A Systematic Review of Microbial Diversity and Probiotic Interventions. Cureus 2025, 17, e85880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazlauskaitė, J.; Žukienė, G.; Rudaitis, V.; Bartkevičienė, D. The Vaginal Microbiota, Human Papillomavirus, and Cervical Dysplasia—A Review. Medicina 2025, 61, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logunov, D.Y.; Scheblyakov, D.V.; Zubkova, O.V.; Shmarov, M.M.; Rakovskaya, I.V.; Gurova, K.V.; Tararova, N.D.; Burdelya, L.G.; Naroditsky, B.S.; Ginzburg, A.L.; et al. Mycoplasma infection suppresses p53, activates NF-κB and cooperates with oncogenic Ras in rodent fibroblast transformation. Oncogene 2008, 27, 4521–4531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Lin, R.; Mao, B.; Tang, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Q.; Cui, S. Lactobacillus crispatus CCFM1339 Inhibits Vaginal Epithelial Barrier Injury Induced by Gardnerella vaginalis in Mice. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zidi, S.; Almawi, W.Y.; Abassi, S.; Khadraoui, N.; Chniba, I.; Chibani, S.; Sahraoui, G.; Mardassi, B.B.A. Genital mycoplasma infections: A hidden factor in cervical cancer progression? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Q.; Wang, S.; Min, Y.; Liu, X.; Fang, J.; Lang, J.; Chen, M. Associations of the gut, cervical, and vaginal microbiota with cervical cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Women’s Health 2025, 25, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, J.; Xia, Q. Role of gut microbiome in cancer immunotherapy: From predictive biomarker to therapeutic target. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2023, 12, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shyanti, R.K.; Greggs, J.; Malik, S.; Mishra, M. Gut dysbiosis impacts the immune system and promotes prostate cancer. Immunol. Lett. 2024, 268, 106883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barykova, Y.A.; Logunov, D.Y.; Shmarov, M.M.; Vinarov, A.Z.; Fiev, D.N.; Vinarova, N.A.; Rakovskaya, I.V.; Baker, P.S.; Shyshynova, I.; Stephenson, A.J.; et al. Association of Mycoplasma hominis infection with prostate cancer. Oncotarget 2011, 2, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, A.T.; Lino, V.d.S.; Marques, L.M.; Martins, D.J.; Junior, A.C.R.B.; Campos, G.B.; Oliveira, C.N.T.; Boccardo, E.; Timenetsky, J. Mycoplasma hominis Causes DNA Damage and Cell Death in Primary Human Keratinocytes. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrisse, S.; Zitvogel, L.; Kroemer, G. Effects of the intestinal microbiota on prostate cancer treatment by androgen deprivation therapy. Microb. Cell 2022, 9, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Dong, T.; Rong, X.; Yang, Y.; Mou, J.; Li, J.; Ge, J.; Mu, X.; Jiang, J. Microbiome in prostate cancer: Pathogenic mechanisms, multi-omics diagnostics, and synergistic therapies. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 151, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, R.; Nejad, S.S.; Fekri, M.; Nejadghaderi, S.A. Advancing prostate cancer treatment: The role of fecal microbiota transplantation as an adjuvant therapy. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2025, 9, 100420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, W.; Zhou, K.; Lei, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhu, H. Gut microbiota shapes cancer immunotherapy responses. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2025, 11, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, D.K.; Baines, K.J.; Jabbarizadeh, B.; Miller, W.H.; Jamal, R.; Ernst, S.; Logan, D.; Belanger, K.; Esfahani, K.; Elkrief, A.; et al. Improved survival in advanced melanoma patients treated with fecal microbiota transplantation using healthy donor stool in combination with anti-PD1: Final results of the MIMic phase 1 trial. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, e012659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, J.; Villegas-Chávez, J.A.; Bunces-Larco, D.; Martín-Aguilera, R.; López-Cortés, A. The microbiome as a therapeutic co-driver in melanoma immuno-oncology. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1673880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaprakash, M.; Kumar, D.V.; Chakraborty, G.; Chakraborty, A.; Kumar, V. Bacteria-mediated cancer therapy (BMCT): Therapeutic applications, clinical insights, and the microbiome as an emerging hallmark of cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2025, 192, 118559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routy, B.; Jackson, T.; Mählmann, L.; Baumgartner, C.K.; Blaser, M.; Byrd, A.; Corvaia, N.; Couts, K.; Davar, D.; Derosa, L.; et al. Melanoma and microbiota: Current understanding and future directions. Cancer Cell 2023, 42, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, C.N.; McQuade, J.L.; Gopalakrishnan, V.; McCulloch, J.A.; Vetizou, M.; Cogdill, A.P.; Khan, A.W.; Zhang, X.; White, M.G.; Peterson, C.B.; et al. Dietary fiber and probiotics influence the gut microbiome and melanoma immunotherapy response. Science 2021, 374, 1632–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Ye, Z.; Ye, Z.; Wang, M.; Cao, Z.; Gao, R.; Zhang, Y. Gut microbiota in brain tumors: An emerging crucial player. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2023, 29, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandita, G.S.A.; Roja, B.; Suresh, P.K. Gut brain axis and gut microbiome in glioblastoma associations, treatment and outcomes. Med. Microecol. 2025, 25, 100131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiadeh, S.M.J.; Chan, W.K.; Rasmusson, S.; Hassan, N.; Joca, S.; Westberg, L.; Elfvin, A.; Mallard, C.; Ardalan, M. Bidirectional crosstalk between the gut microbiota and cellular compartments of brain: Implications for neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric disorders. Transl. Psychiatry 2025, 15, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahboob, A.; Shin, C.; Almughanni, S.; Hornakova, L.; Kubatka, P.; Büsselberg, D. The Gut Nexus: Unraveling Microbiota-Mediated Links Between Type 2 Diabetes and Colorectal Cancer. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk, A.; Sladowska, G.E.; Strzalka-Mrozik, B. The Role of the Gut Microbiota in Modulating Signaling Pathways and Oxidative Stress in Glioma Therapies. Cancers 2025, 17, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-C.; Wu, B.-S.; Jiang, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.-F.; Ma, C.; Li, Y.-R.; Yao, J.; Jin, X.-Q.; Li, Z.-Q. Temozolomide-Induced Changes in Gut Microbial Composition in a Mouse Model of Brain Glioma. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2021, 15, 1641–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mir, R.; Albarqi, S.A.; Albalawi, W.; Alatwi, H.E.; Alatawy, M.; Bedaiwi, R.I.; Almotairi, R.; Husain, E.; Zubair, M.; Alanazi, G.; et al. Emerging Role of Gut Microbiota in Breast Cancer Development and Its Implications in Treatment. Metabolites 2024, 14, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbaniak, C.; Gloor, G.B.; Brackstone, M.; Scott, L.; Tangney, M.; Reid, G. The Microbiota of Breast Tissue and Its Association with Breast Cancer. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 5039–5048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Wang, X.; Guo, Y.; Yan, J.; Abuduwaili, A.; Aximujiang, K.; Yan, J.; Wu, M. Gut microbiota influence tumor development and Alter interactions with the human immune system. Correction to: Gut microbiota influence tumor development and Alter interactions with the human immune system. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 40, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Liu, M.; Deng, X.; Tang, Y.; Zheng, S.; Ou, X.; Tang, H.; Xie, X.; Wu, M.; Zou, Y. Gut microbiota reshapes cancer immunotherapy efficacy: Mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. iMeta 2024, 3, e156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ransohoff, J.D.; Ritter, V.; Purington, N.; Andrade, K.; Han, S.; Liu, M.; Liang, S.-Y.; John, E.M.; Gomez, S.L.; Telli, M.L.; et al. Antimicrobial exposure is associated with decreased survival in triple-negative breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Qin, S.; Gu, R.; Ji, S.; Wu, G.; Gu, K. Amuc_1434 from Akkermansia muciniphila Enhances CD8+ T Cell-Mediated Anti-Tumor Immunity by Suppressing PD-L1 in Colorectal Cancer. FASEB J. 2025, 39, e70540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Peng, Z.; Liu, X.; Chen, J.; Zheng, X. Role of lung and gut microbiota on lung cancer pathogenesis. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 147, 2177–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Xie, S.; Lv, D.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, J.; Zeng, L.; Chen, Y. A reduction in the butyrate producing species Roseburia spp. and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is associated with chronic kidney disease progression. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2016, 109, 1389–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safarchi, A.; Al-Qadami, G.; Tran, C.D.; Conlon, M. Understanding dysbiosis and resilience in the human gut microbiome: Biomarkers, interventions, and challenges. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1559521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, F.; Yuan, L.; Yang, F.; Wu, G.; Jiang, X. Emerging roles of fibroblast growth factor 21 in critical disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 1053997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Chen, H.; Li, H.; Zheng, M.; Zuo, X.; Wang, W.; Wang, S.; Lu, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; et al. Intratumor microbiome-derived butyrate promotes lung cancer metastasis. Cell Rep. Med. 2024, 5, 101488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Pan, C.; Jiang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Chen, F.; Zhao, Y.; Liang, H.; Wang, W.; He, J.; Xu, X.; et al. Causality of genetically determined gut microbiota on lung cancer: Mendelian randomization study. J. Thorac. Dis. 2025, 17, 4062–4078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Wang, L.-F.; Hu, W.-T.; Liang, Z.-G. The gut microbiome in lung cancer: From pathogenesis to precision therapy. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1606684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guijarro-Muñoz, I.; Compte, M.; Álvarez-Cienfuegos, A.; Álvarez-Vallina, L.; Sanz, L. Lipopolysaccharide Activates Toll-like Receptor 4 (TLR4)-mediated NF-κB Signaling Pathway and Proinflammatory Response in Human Pericytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 2457–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Wang, J.; Gu, Z.; Qiu, X.; Yuan, M.; Ke, H.; Deng, R. Porphyromonas gingivalis and Fusobacterium nucleatum synergistically strengthen the effect of promoting oral squamous cell carcinoma progression. Infect. Agents Cancer 2025, 20, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.-R.; Li, J.; Cai, W.; Lai, J.Y.H.; McKinnie, S.M.K.; Zhang, W.-P.; Moore, B.S.; Zhang, W.; Qian, P.-Y. Macrocyclic colibactin induces DNA double-strand breaks via copper-mediated oxidative cleavage. Nat. Chem. 2019, 11, 880–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, J.; Altamirano-Colina, A.; Lopez-Cortes, A. The vaginal microbiome in HPV persistence and cervical cancer progression. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1634251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Fan, N.; Ma, S.; Cheng, X.; Yang, X.; Wang, G. Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis: Pathogenesis, Diseases, Prevention, and Therapy. MedComm 2025, 6, e70168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Qi, P.; Shu, L.; Ding, Y.; Zeng, P.; Wen, G.; Xiong, Y.; Deng, H. Dysbiosis and extraintestinal cancers. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 44, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yang, M.; Dong, W.; Liu, T.; Song, X.; Gu, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Abla, Z.; Qiao, X.; et al. Gut Dysbiosis and Abnormal Bile Acid Metabolism in Colitis-Associated Cancer. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2021, 2021, 6645970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, J.Y.L.; Ferrell, J.M. Bile acid receptors FXR and TGR5 signaling in fatty liver diseases and therapy. Am. J. Physiol. Liver Physiol. 2020, 318, G554–G573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz, O.; Jungas, T.; Verbeke, P.; Ojcius, D.M. Activation of the Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/Akt Pathway Contributes to Survival of Primary Epithelial Cells Infected with the Periodontal Pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect. Immun. 2004, 72, 3743–3751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayuningtyas, N.F.; Mahdani, F.Y.; Pasaribu, T.A.S.; Chalim, M.; Ayna, V.K.P.; Santosh, A.B.R.; Santacroce, L.; Surboyo, M.D.C. Role of Candida albicans in Oral Carcinogenesis. Pathophysiology 2022, 29, 650–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araji, G.; Maamari, J.; Ahmad, F.A.; Zareef, R.; Chaftari, P.; Yeung, S.-C.J. The Emerging Role of the Gut Microbiome in the Cancer Response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Narrative Review. J. Immunother. Precis. Oncol. 2021, 5, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusmaulemova, A.; Kurentay, B.; Bayanbek, D.; Kulmambetova, G. Comparative insights into Fusobacterium nucleatum and Helicobacter pylori in human cancers. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1677795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, U.; Ho, K.; Hwang, E.K.B.; Peña, C.B.; Brouwer, J.; Hoffman, K.; Betel, D.; Sonnenberg, G.F.; Faltas, B.; Saxena, A.; et al. Impact of Use of Antibiotics on Response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and Tumor Microenvironment. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 44, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nigam, M.; Panwar, A.S.; Singh, R.K. Orchestrating the fecal microbiota transplantation: Current technological advancements and potential biomedical application. Front. Med. Technol. 2022, 4, 961569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sędzikowska, A.; Szablewski, L. Human Gut Microbiota in Health and Selected Cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Zhang, L.; Leng, X.X.; Xie, Y.L.; Kang, Z.R.; Zhao, L.C.; Song, L.H.; Zhou, C.B.; Fang, J.Y. Fusobacterium nucleatum induces chemoresistance in colorectal cancer by inhibiting pyroptosis via the Hippo pathway. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2333790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Song, S.; Liu, J.; Chen, F.; Li, X.; Wu, G. Gut microbiota as a new target for anticancer therapy: From mechanism to means of regulation. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2025, 11, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somodi, C.; Dora, D.; Horváth, M.; Szegvari, G.; Lohinai, Z. Gut microbiome changes and cancer immunotherapy outcomes associated with dietary interventions: A systematic review of preclinical and clinical evidence. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoodvandi, A.; Fallahi, F.; Tamtaji, O.R.; Tajiknia, V.; Banikazemi, Z.; Fathizadeh, H.; Abbasi-Kolli, M.; Aschner, M.; Ghandali, M.; Sahebkar, A.; et al. An Update on the Effects of Probiotics on Gastrointestinal Cancers. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 680400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; An, Y.; Dong, Y.; Chu, Q.; Wei, J.; Wang, B.; Cao, H. Fecal microbiota transplantation: No longer cinderella in tumour immunotherapy. EBioMedicine 2024, 100, 104967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cancer Type | Microbes | Oncogenesis Mechanism | Therapy Modulation | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal cancer (CRC) | Fusobacterium nucleatum, Bacteroides fragilis, Escherichia coli | Wnt/β-catenin activation, DNA damage, inflammation | Resistance to 5-FU/oxaliplatin; ICI response linked to Akkermansia | Microbial profiling may guide chemo-immunotherapy strategies |

| Gastric cancer | Helicobacter pylori, Prevotella, Neisseria | CagA/VacA-induced DNA damage; nitrosating bacteria generate carcinogens | Alters chemotherapy efficacy; probiotics reduce toxicity | Eradication plus microbiome support may lower cancer risk |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) | Veillonella, Streptococcus, Akkermansia | Bile acid dysregulation, LPS-driven inflammation | ICI outcomes linked to Akkermansia enrichment | Microbiome as biomarker for immunotherapy response |

| Gallbladder cancer | Enterobacter, Klebsiella, Streptococcus | Bile acid imbalance, gallstone biofilms, chronic inflammation | Limited evidence; bile dysbiosis may influence drug metabolism | Potential role of probiotics in biliary cancer prevention |

| Esophageal cancer | Fusobacterium, Porphyromonas, Prevotella | Dysbiosis in Barrett’s esophagus, inflammation, nitric oxide generation | Microbial diversity predicts ICI response; probiotics mitigate radiation toxicity | Microbiome may serve as risk marker and therapeutic adjunct |

| Pancreatic cancer | Pseudomonas, Fusobacterium, Gammaproteobacteria | SCFA loss; TMAO/3-IAA promote growth and immunosuppression | Gammaproteobacteria metabolize gemcitabine; FMT improves ICI efficacy | Microbial modulation may overcome chemoresistance |

| Oral SCC | Porphyromonas gingivalis, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Candida | Inflammation, EMT induction, nitrosamine production | Oral probiotics reduce mucositis; may support systemic therapy | Oral–gut microbial axis relevant for prevention and therapy |

| Cervical cancer | Gardnerella, Mycoplasma, Atopobium | Dysbiosis impairs HPV clearance, genomic instability | Vaginal microbiome influences radiotherapy outcomes | Microbiome restoration could reduce recurrence risk |

| Prostate cancer | Mycoplasma, Akkermansia, SCFA-producing taxa | Inflammation, DNA damage, altered androgen metabolism | Gut microbes modulate ADT and ICI outcomes | Microbiome-targeted therapies may delay resistance |

| Melanoma | Akkermansia, Bifidobacterium, Faecalibacterium | Immune modulation, enhanced T-cell activation | ICI efficacy linked to microbial diversity; FMT restores response | Benchmark cancer for microbiome–immunotherapy translation |

| Glioma/glioblastoma (brain tumors) | Akkermansia muciniphila, Bifidobacterium, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Roseburia, Escherichia coli (LPS-producing), Clostridium spp. | Dysbiosis reduces SCFA-producing taxa (e.g., Faecalibacterium, Roseburia), weakening anti-inflammatory signaling and disrupting the gut–brain axis. Bacterial metabolites and endotoxins cross a compromised gut barrier, inducing systemic inflammation, IL-6/TNF-α release, and microglial activation that promotes tumor proliferation and immune escape | Antibiotic-induced dysbiosis impairs ICI efficacy; reintroduction of Akkermansia or Bifidobacterium restores T-cell activation and response. SCFAs modulate microglial phenotype and BBB integrity, influencing temozolomide metabolism and local immune tone | Gut–brain axis modulation via probiotics, prebiotics, or FMT may enhance ICI response and chemotherapy effectiveness; microbial biomarkers could help predict treatment sensitivity and neuroinflammation risk |

| Breast cancer | Lactobacillus, Bacteroides, Clostridium, Methylobacterium radiotolerans, Escherichia coli, Bifidobacterium | Gut dysbiosis alters estrobolome activity → increased β-glucuronidase → higher circulating estrogens; local bacteria (E. coli, Methylobacterium) induce DNA breaks and oxidative stress; immune modulation via pro-inflammatory signaling | Akkermansia muciniphila and Bifidobacterium enhance ICI efficacy; antibiotics impair chemo-/immunotherapy response; probiotics improve mucosal repair | Microbial profiling may identify hormone-responsive risk; probiotic and dietary fiber interventions could enhance treatment efficacy and reduce toxicity |

| Lung cancer | Streptococcus, Veillonella, Prevotella, Bacteroides, Akkermansia, Ruminococcaceae | Chronic airway and systemic inflammation; IL-17/IL-6–driven epithelial proliferation; reduced SCFA-producing taxa leading to impaired anti-inflammatory signaling | Gut microbial diversity and enrichment of Akkermansia and Ruminococcaceae associated with improved ICI response; antibiotic-induced dysbiosis reduces immunotherapy efficacy | Microbiome profiling may predict immunotherapy response and guide antibiotic stewardship during ICI treatment |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Peddireddi, R.S.S.; Kuchana, S.K.; Kode, R.; Khammammettu, S.; Koppanatham, A.; Mattigiri, S.; Gobburi, H.; Alahari, S.K. Role of Gut Microbiome in Oncogenesis and Oncotherapies. Cancers 2026, 18, 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010099

Peddireddi RSS, Kuchana SK, Kode R, Khammammettu S, Koppanatham A, Mattigiri S, Gobburi H, Alahari SK. Role of Gut Microbiome in Oncogenesis and Oncotherapies. Cancers. 2026; 18(1):99. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010099

Chicago/Turabian StylePeddireddi, Renuka Sri Sai, Sai Kiran Kuchana, Rohith Kode, Saketh Khammammettu, Aishwarya Koppanatham, Supriya Mattigiri, Harshavardhan Gobburi, and Suresh K. Alahari. 2026. "Role of Gut Microbiome in Oncogenesis and Oncotherapies" Cancers 18, no. 1: 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010099

APA StylePeddireddi, R. S. S., Kuchana, S. K., Kode, R., Khammammettu, S., Koppanatham, A., Mattigiri, S., Gobburi, H., & Alahari, S. K. (2026). Role of Gut Microbiome in Oncogenesis and Oncotherapies. Cancers, 18(1), 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010099