Risk of Malnutrition in Digestive System Cancers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Selection Process

2.4. Data Collection Process and Data Items

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.6. Synthesis Methods

3. Results

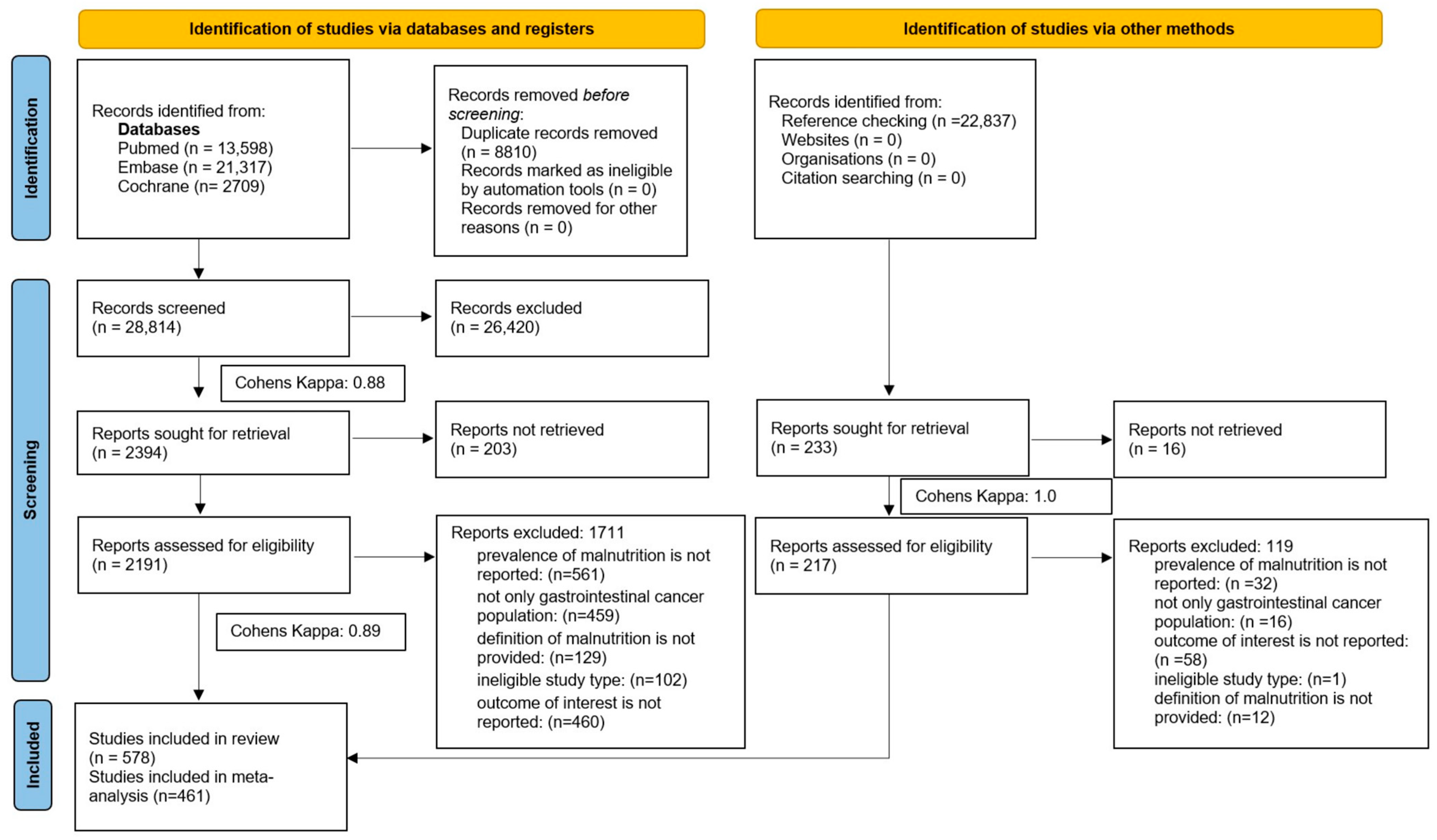

3.1. Search and Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Association of Population Characteristics with Malnutrition-Related Complication Risk, Malnutrition Risk, Diagnosis of Malnutrition, and Cachexia

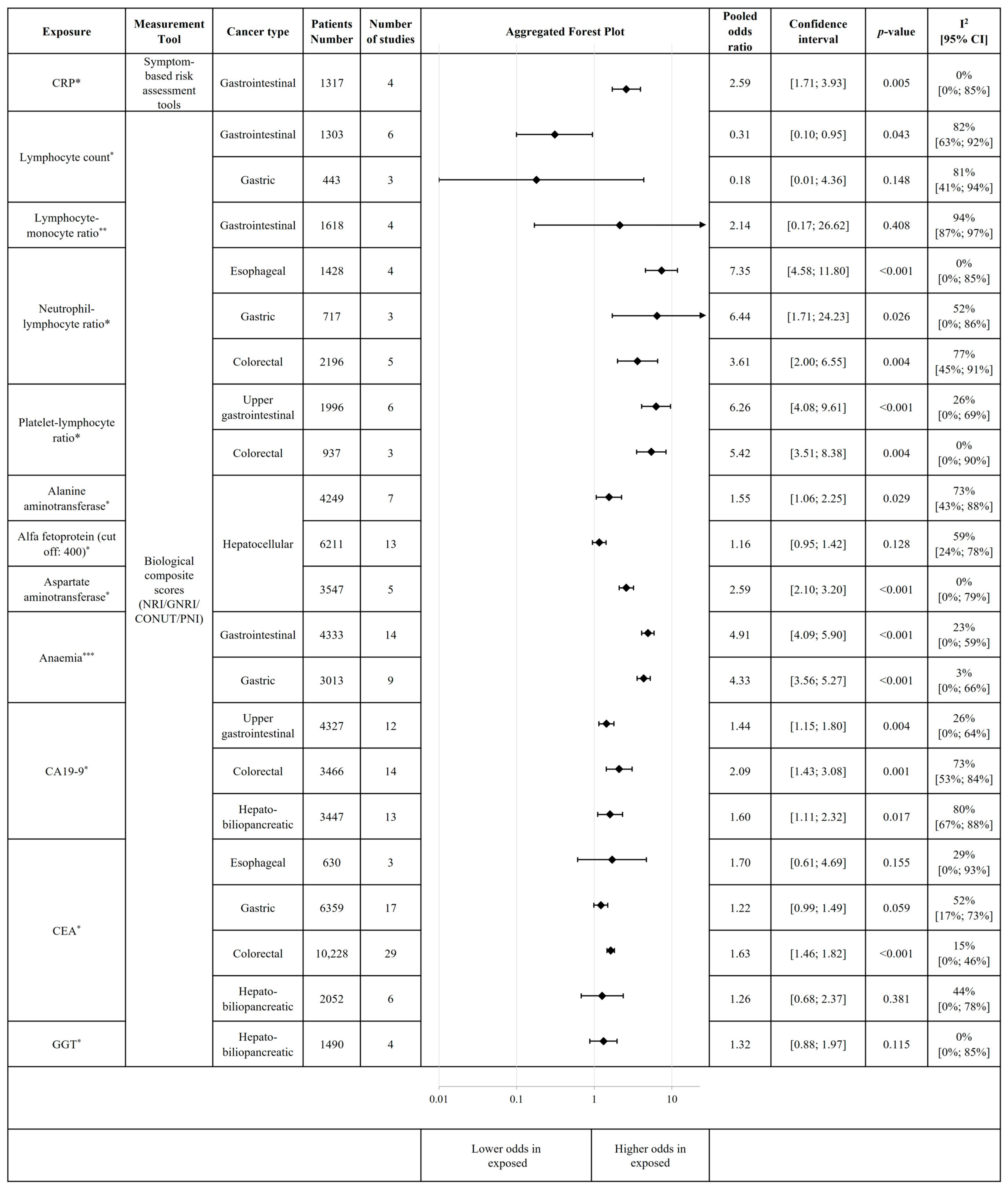

3.4. Association of Inflammation and Other Biological Parameters with the Risk of Malnutrition and Malnutrition-Related Complications

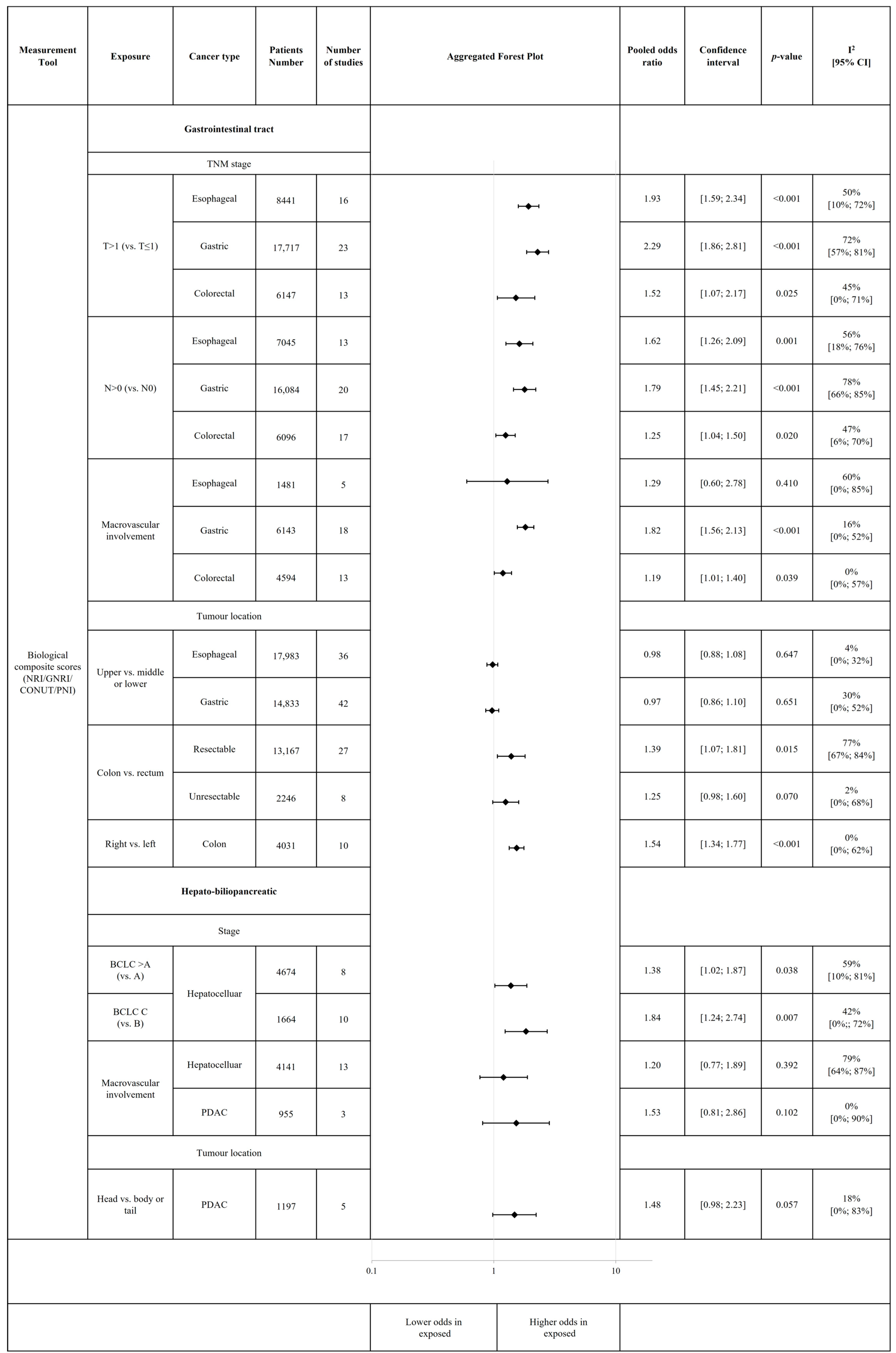

3.5. Association of Tumour Characteristics and Treatment with Risk of Malnutrition and Malnutrition-Related Complications

3.6. Risk of Bias Assessment and Sensitivity Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Implications for Practice

4.3. Implications for Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arnold, M.; Abnet, C.C.; Neale, R.E.; Vignat, J.; Giovannucci, E.L.; McGlynn, K.A.; Bray, F. Global burden of 5 major types of gastrointestinal cancer. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 335–349.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, T.; Sari, I.N.; Wijaya, Y.T.; Julianto, N.M.; Muhammad, J.A.; Lee, H.; Chae, J.H.; Kwon, H.Y. Cancer cachexia: Molecular mechanisms and treatment strategies. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2023, 16, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Quan, Y.; Wang, X.; Wei, X.; Shen, X.; Li, X.; Liang, T. Global epidemiological characteristics of malnutrition in cancer patients: A comprehensive meta-analysis and systematic review. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, B.; Saunders, J. Malnutrition and undernutrition: Causes, consequences, assessment and management. Medicine 2023, 51, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arends, J.; Baracos, V.; Bertz, H.; Bozzetti, F.; Calder, P.C.; Deutz, N.E.P.; Erickson, N.; Laviano, A.; Lisanti, M.P.; Lobo, D.N.; et al. ESPEN expert group recommendations for action against cancer-related malnutrition. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 1187–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillanne, O.; Morineau, G.; Dupont, C.; Coulombel, I.; Vincent, J.-P.; Nicolis, I.; Benazeth, S.; Cynober, L.; Aussel, C. Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index: A new index for evaluating at-risk elderly medical patients. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 82, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzby, G.P.; Mullen, J.L.; Matthews, D.C.; Hobbs, C.L.; Rosato, E.F. Prognostic nutritional index in gastrointestinal surgery. Am. J. Surg. 1980, 139, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ulíbarri, J.I.; González-Madroño, A.; de Villar, N.G.; González, P.; González, B.; Mancha, A.; Rodríguez, F.; Fernández, G. CONUT: A tool for controlling nutritional status. First validation in a hospital population. Nutr. Hosp. 2005, 20, 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Veterans Affairs Total Parenteral Nutrition Cooperative Study Group. Perioperative total parenteral nutrition in surgical patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991, 325, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondrup, J.; Rasmussen, H.H.; Hamberg, O.; Stanga, Z.; An ad hoc ESPEN Working Group. Nutritional risk screening (NRS 2002): A new method based on an analysis of controlled clinical trials. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 22, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elia, M. The ‘MUST’ report. In Nutritional Screening of Adults: A Multidisciplinary Responsibility; BAPEN: Letchworth, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Guigoz, Y.; Vellas, B.; Garry, P. Mini Nutritional Assessment: A practical assessment tool for grading the nutritional state of elderly patients. The mini nutritional assessment: MNA. Nutr. Elder. 1997, 15, 116–122. [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein, L.Z.; Harker, J.O.; Salvà, A.; Guigoz, Y.; Vellas, B. Screening for undernutrition in geriatric practice: Developing the short-form mini-nutritional assessment (MNA-SF). J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2001, 56, M366–M372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, M.; Capra, S.; Bauer, J.; Banks, M. Development of a valid and reliable malnutrition screening tool for adult acute hospital patients. Nutrition 1999, 15, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Detsky, A.S.; McLaughlin, J.R.; Baker, J.P.; Johnston, N.; Whittaker, S.; Mendelson, R.A.; Jeejeebhoy, K.N. What is subjective global assessment of nutritional status? J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 1987, 11, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottery, F.D. Definition of standardized nutritional assessment and interventional pathways in oncology. Nutrition 1996, 12, S15–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruizenga, H.M.; Seidell, J.; de Vet, H.C.; Wierdsma, N. Development and validation of a hospital screening tool for malnutrition: The short nutritional assessment questionnaire (SNAQ©). Clin. Nutr. 2005, 24, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cederholm, T.; Jensen, G.; Correia, M.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Fukushima, R.; Higashiguchi, T.; Baptista, G.; Barazzoni, R.; Blaauw, R.; Coats, A. GLIM criteria for the diagnosis of malnutrition—A consensus report from the global clinical nutrition community. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2019, 10, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cederholm, T.; Jensen, G.L.; Correia, M.I.T.D.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Fukushima, R.; Pisprasert, V.; Blaauw, R.; Braz, D.C.; Carrasco, F.; Cruz Jentoft, A.J.; et al. The GLIM consensus approach to diagnosis of malnutrition: A 5-year update. Clin. Nutr. 2025, 49, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serón-Arbeloa, C.; Labarta-Monzón, L.; Puzo-Foncillas, J.; Mallor-Bonet, T.; Lafita-López, A.; Bueno-Vidales, N.; Montoro-Huguet, M. Malnutrition Screening and Assessment. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, O.; Sahinli, H.; Yazilitas, D. Assessment of malnutrition in cancer patients: A geriatric approach with the mini nutritional assessment. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1590137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arends, J. Malnutrition in cancer patients: Causes, consequences and treatment options. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 50, 107074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attar, A.; Malka, D.; Sabaté, J.M.; Bonnetain, F.; Lecomte, T.; Aparicio, T.; Locher, C.; Laharie, D.; Ezenfis, J.; Taieb, J. Malnutrition is high and underestimated during chemotherapy in gastrointestinal cancer: An AGEO prospective cross-sectional multicenter study. Nutr. Cancer 2012, 64, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patini, R.; Favetti Giaquinto, E.; Gioco, G.; Castagnola, R.; Perrotti, V.; Rupe, C.; Di Gennaro, L.; Nocca, G.; Lajolo, C. Malnutrition as a Risk Factor in the Development of Oral Cancer: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analyses. Nutrients 2024, 16, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Xu, W.; Zhang, H.; Fan, Y. Association between risk of malnutrition defined by patient-generated subjective global assessment and adverse outcomes in patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health Nutr. 2024, 27, e105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szentesi, A.; Hegyi, P.; on behalf of the Hungarian Pancreatic Study Group. The 12-Year Experience of the Hun-garian Pancreatic Study Group. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegyi, P.; Varró, A. Systems education can train the next generation of scientists and clinicians. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 3399–3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beirer, A. Malnutrition and cancer, diagnosis and treatment. Memo-Mag. Eur. Med. Oncol. 2021, 14, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, J.A.; van der Windt, D.A.; Cartwright, J.L.; Côté, P.; Bombardier, C. Assessing bias in studies of prognostic factors. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013, 158, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IntHout, J.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Borm, G.F. The Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method for random effects meta-analysis is straightforward and considerably outperforms the standard DerSimonian-Laird method. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robins, J.; Greenland, S.; Breslow, N.E. A General Estimator for the Variance of the Mantel Haenszel Odds Ratio. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1986, 124, 719–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantel, N.; Haenszel, W. Statistical Aspects of the Analysis of Data from Retrospective Studies of Disease. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1959, 22, 719–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knapp, G.; Hartung, J. Improved tests for a random effects meta-regression with a single covariate. Stat. Med. 2003, 22, 2693–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paule, R.C.; Mandel, J. Consensus values and weighting factors. J. Res. Natl. Bur. Stand. 1982, 87, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veroniki, A.A.; Jackson, D.; Viechtbauer, W.; Bender, R.; Bowden, J.; Knapp, G.; Kuss, O.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Langan, D.; Salanti, G. Methods to estimate the between-study variance and its uncertainty in meta-analysis. Res. Synth. Methods 2016, 7, 55–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 1539–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbord, R.M.; Harris, R.J.; Sterne, J.A.C. Updated Tests for Small-study Effects in Meta-analyses. Stata J. 2009, 9, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbord, R.M.; Egger, M.; Sterne, J.A. A modified test for small-study effects in meta-analyses of controlled trials with binary endpoints. Stat. Med. 2006, 25, 3443–3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrer, M.; Cuijpers, P.; Furukawa, T.A.; Ebert, D.D. Doing Meta-Analysis with R: A Hands-On Guide, 1st ed.; Chapman & Hall/CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA; London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Schwarzer, G. Meta: General Package for Meta-Analysis. Available online: https://github.com/guido-s/meta/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Harrer, M.; Cuijpers, P.; Furukawa, T.; Ebert, D.D.; Dmetar, D. Companion R Package for The Guide ‘Doing Meta-Analysis in R’. Available online: http://dmetar.protectlab.org/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Weimann, A.; Braga, M.; Harsanyi, L.; Laviano, A.; Ljungqvist, O.; Soeters, P.; Jauch, K.; Kemen, M.; Hiesmayr, J.; Horbach, T. ESPEN guidelines on enteral nutrition: Surgery including organ transplantation. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 25, 224–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cederholm, T.; Bosaeus, I.; Barazzoni, R.; Bauer, J.; Van Gossum, A.; Klek, S.; Muscaritoli, M.; Nyulasi, I.; Ockenga, J.; Schneider, S. Diagnostic criteria for malnutrition—An ESPEN consensus statement. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 34, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, F.K.; Wang, L.; Zhang, W.C.; Wang, L.D.; Zhao, L.S. Preoperative Prognostic Nutritional Index is a Significant Predictor of Survival in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Patients. Nutr. Cancer 2021, 73, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akgul, C.; Colapkulu-Akgul, N.; Gunes, A. Prognostic Value of Systemic Inflammatory Markers and Scoring Systems in Predicting Postoperative 30-Day Complications and Mortality in Colorectal Cancer Surgery: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Analysis. Ann. Ital. Chir. 2024, 95, 636–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiraoka, A.; Kumada, T.; Tada, T.; Hirooka, M.; Kariyama, K.; Tani, J.; Atsukawa, M.; Takaguchi, K.; Itobayashi, E.; Fukunishi, S.; et al. Geriatric nutritional risk index as an easy-to-use assessment tool for nutritional status in hepatocellular carcinoma treated with atezolizumab plus bevacizumab. Hepatol. Res. 2023, 53, 1031–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wu, X.; Yu, X.; Liu, J.; Zhou, H.; Wu, H.; Cui, X.; Geng, S.; Li, Z. The investigation of factors influencing the prognostic nutritional index in patients with esophageal cancer—A cross-sectional study. J. Thorac. Dis. 2025, 17, 5065–5077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schünemann, H.; Brożek, J.; Guyatt, G.; Oxman, A. (Eds.) GRADE Handbook for Grading Quality of Evidence and Strength of Recommendations. Available online: https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/handbook/handbook.html (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Pellegrino, A.; Tiidus, P.M.; Vandenboom, R. Mechanisms of estrogen influence on skeletal muscle: Mass, regeneration, and mitochondrial function. Sports Med. 2022, 52, 2853–2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltais, M.; Desroches, J.; Dionne, I.J. Changes in muscle mass and strength after menopause. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact. 2009, 9, 186–197. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Z.; Munker, S.; Wang, C.; Xu, L.; Ye, H.; Chen, H.; Xu, G.; Zhang, H.; Chen, L.; Yu, C. Association between alcohol intake, overweight, and serum lipid levels and the risk analysis associated with the development of dyslipidemia. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2014, 8, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addolorato, G.; Capristo, E.; Marini, M.; Santini, P.; Scognamiglio, U.; Attilia, M.L.; Messineo, D.; Sasso, G.F.; Gasbarrini, G.; Ceccanti, M. Body composition changes induced by chronic ethanol abuse: Evaluation by dual energy x-ray absorptiometry. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2000, 95, 2323–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.F.; Gusmão-Sena, M.H.L.; Oliveira, L.C.G.; Gomes, T.S.; do Nascimento, T.V.N.; Gobatto, A.L.N.; Sampaio, L.R.; Barreto-Medeiros, J.M. Inflammatory, nutritional and clinical parameters of individuals with chronic kidney disease undergoing conservative treatment. Nutr. Hosp. 2015, 32, 1376–1381. [Google Scholar]

- Alkan, Ş.B.; Artaç, M.; Rakıcıoğlu, N. The relationship between nutritional status and handgrip strength in adult cancer patients: A cross-sectional study. Support. Care Cancer 2018, 26, 2441–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daabiss, M. American Society of Anaesthesiologists physical status classification. Indian J. Anaesth. 2011, 55, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fearon, K.; Arends, J.; Baracos, V. Understanding the mechanisms and treatment options in cancer cachexia. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 10, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, Y.L.; Teoh, S.E.; Yaow, C.Y.L.; Lin, D.J.; Masuda, Y.; Han, M.X.; Yeo, W.S.; Ng, Q.X. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Clinical Use of Megestrol Acetate for Cancer-Related Anorexia/Cachexia. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapała, A.; Różycka, K.; Grochowska, E.; Gazi, A.; Motacka, E.; Folwarski, M. Cancer, malnutrition and inflammatory biomarkers. Why do some cancer patients lose more weight than others? Contemp. Oncol. 2025, 29, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Xu, D.; Song, H.; Qiu, B.; Tian, D.; Li, Z.; Ji, Y.; Wang, J. Inflammation and nutrition-based biomarkers in the prognosis of oesophageal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e048324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macciò, A.; Madeddu, C.; Gramignano, G.; Mulas, C.; Tanca, L.; Cherchi, M.C.; Floris, C.; Omoto, I.; Barracca, A.; Ganz, T. The role of inflammation, iron, and nutritional status in cancer-related anemia: Results of a large, prospective, observational study. Haematologica 2015, 100, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandasamy, A.; Pottakkat, B. Alpha-fetoprotein: A molecular bootstrap for hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Immuno Oncol. 2020, 5, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goonetilleke, K.; Siriwardena, A. Systematic review of carbohydrate antigen (CA 19-9) as a biochemical marker in the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. (EJSO) 2007, 33, 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Shi, S.; Liang, C.; Liang, D.; Xu, W.; Ji, S.; Zhang, B.; Ni, Q.; Xu, J.; Yu, X. Diagnostic and prognostic value of carcinoembryonic antigen in pancreatic cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. OncoTargets Ther. 2017, 10, 4591–4598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaban, D.V.; Marin, F.S.; Manucu, G.; Zoican, A.; Ciochina, M.; Mina, V.; Patoni, C.; Vladut, C.; Bucurica, S.; Costache, R.S.; et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes in carbohydrate antigen 19-9 negative pancreatic cancer. World J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 13, 630–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, H.; Nugent, Z.; Demers, A.A.; Kliewer, E.V.; Mahmud, S.M.; Bernstein, C.N. The reduction in colorectal cancer mortality after colonoscopy varies by site of the cancer. Gastroenterology 2010, 139, 1128–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Q.; Wang, G.; Jiang, L.; Wei, Q.; Luo, C.; Chen, L.; Ying, J. Systemic Inflammatory Markers of Resectable Colorectal Cancer Patients with Different Mismatch Repair Gene Status. Cancer Manag. Res. 2021, 13, 2925–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasprzak, A. The role of tumor microenvironment cells in colorectal cancer (CRC) cachexia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeyen, G.; Berrevoet, F.; Borbath, I.; Geboes, K.; Peeters, M.; Topal, B.; Van Cutsem, E.; Van Laethem, J.L. Expert opinion on management of pancreatic exocrine insufficiency in pancreatic cancer. ESMO Open 2022, 7, 100386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegyi, P.; Erőss, B.; Izbéki, F.; Párniczky, A.; Szentesi, A. Accelerating the translational medicine cycle: The Academia Europaea pilot. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1317–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegyi, P.; Petersen, O.H.; Holgate, S.; Erőss, B.; Garami, A.; Szakács, Z.; Dobszai, D.; Balaskó, M.; Kemény, L.; Peng, S. Academia Europaea position paper on translational medicine: The cycle model for translating scientific results into community benefits. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Subgroups | ||

|---|---|---|

| Cancer type | Gastrointestinal tract | Esophageal |

| Gastric | ||

| Colorectal | ||

| Upper gastrointestinal tract | Esophageal | |

| Gastric | ||

| Hepato-biliopancreatic | Biliary tract | |

| Hepatocellular | ||

| Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | ||

| Measurement tools | Malnutrition risk screening based on symptoms and signs | NRS-2002 [10] |

| MUST [11] | ||

| MNA [12] | ||

| MNA-SF [13] | ||

| MST [14] | ||

| SGA [15] | ||

| PG-SGA [16] | ||

| SNAQ [17] | ||

| Tools evaluating the risk of malnutrition-related complications | GNRI [6] | |

| PNI [7] | ||

| CONUT [8] | ||

| NRI [9] | ||

| Diagnosis of malnutrition | GLIM criteria [18] | |

| Previous guidelines * | ||

| Cachexia ** | ||

| Risk Factor Category | Measurement Tool | Confirmed Risk Factors for Malnutrition | Cancer Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population characteristics | Biological composite scores (NRI, GNRI, CONUT PNI) | Age ≥ 65 | Gastrointestinal |

| Esophageal | |||

| Gastric | |||

| Colorectal | |||

| Age ≥ 60 | Esophageal | ||

| Gastric | |||

| Colorectal | |||

| Sign and symptom-based risk assessment tools | Female sex | Gastric | |

| Biological composite scores (NRI, GNRI, CONUT, PNI) | Hepatocellular | ||

| Cachexia | Gastric | ||

| Colorectal | |||

| Biological composite scores (NRI, GNRI, CONUT, PNI) | Comorbidities | Upper gastrointestinal | |

| Biological composite scores (NRI, GNRI, CONUT, PNI) | Chronic kidney disease | Gastrointestinal | |

| Sign and symptom-based risk assessment tools | ASA score ≥ 3 | Colorectal | |

| Malnutrition diagnosis according to GLIM criteria | Gastrointestinal | ||

| Biological composite scores (NRI, GNRI, CONUT, PNI) | Esophageal | ||

| Gastric | |||

| Colorectal | |||

| Malnutrition based on guidelines | Gastrointestinal | ||

| Biological composite scores (NRI, GNRI, CONUT, PNI) | ECOG ≥ 2 | HBP cancer | |

| Colorectal | |||

| Gastric | |||

| Biological parameters | Biological composite scores (NRI, GNRI, CONUT, PNI) | Elevated CRP | Gastrointestinal |

| Decreased Lymphocyte count | Gastrointestinal | ||

| Elevated Neutrophil–Lymphocyte ratio | Esophageal | ||

| Gastric | |||

| Colorectal | |||

| Elevated Platelet–Lymphocyte ratio | Upper gastrointestinal | ||

| Colorectal | |||

| Elevated Alanine-aminotransferase | Hepatocellular | ||

| Elevated Aspartate-aminotransferase | Hepatocellular | ||

| Anaemia | Gastrointestinal | ||

| Gastric | |||

| Elevated CA19-9 | Upper gastrointestinal | ||

| Colorectal | |||

| HBP cancer | |||

| Elevated CEA | Colorectal | ||

| Tumour characteristics | Biological composite scores (NRI, GNRI, CONUT, PNI) | T > 1 stage | Esophageal |

| Gastric | |||

| N > 0 stage | Esophageal | ||

| Gastric | |||

| Colorectal | |||

| Macrovascular involvement | Gastric | ||

| Colorectal | |||

| Colon tumour location (vs. rectum) | Colorectal (resectable stage) | ||

| Right tumour location (vs. left) | Colon cancer | ||

| BCLC B or C (vs. A) | Hepatocellular | ||

| BCLC C (vs. B) | |||

| Child–Pugh class B or C (vs. A) | |||

| Therapy | Biological composite scores (NRI, GNRI, CONUT, PNI) | Neoadjuvant therapy | Colorectal |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Budai, B.C.; Martinekova, P.; Cai, G.; Dobszai, D.; Fekete, L.; Normann, H.A.; Németh, J.; Fazekas, A.; Szalai, E.Á.; Szentesi, A.; et al. Risk of Malnutrition in Digestive System Cancers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2026, 18, 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010080

Budai BC, Martinekova P, Cai G, Dobszai D, Fekete L, Normann HA, Németh J, Fazekas A, Szalai EÁ, Szentesi A, et al. Risk of Malnutrition in Digestive System Cancers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers. 2026; 18(1):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010080

Chicago/Turabian StyleBudai, Bettina Csilla, Petrana Martinekova, Gefu Cai, Dalma Dobszai, Lili Fekete, Hanne Aspelund Normann, Jázmin Németh, Alíz Fazekas, Eszter Ágnes Szalai, Andrea Szentesi, and et al. 2026. "Risk of Malnutrition in Digestive System Cancers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Cancers 18, no. 1: 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010080

APA StyleBudai, B. C., Martinekova, P., Cai, G., Dobszai, D., Fekete, L., Normann, H. A., Németh, J., Fazekas, A., Szalai, E. Á., Szentesi, A., Drug, V. L., Hegyi, P., & Bunduc, S. (2026). Risk of Malnutrition in Digestive System Cancers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers, 18(1), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010080