Assessment of Tumor Margin and Heterogeneity of Colorectal Cancer Using Imaging Mass Spectrometry and Image Segmentation

Simple Summary

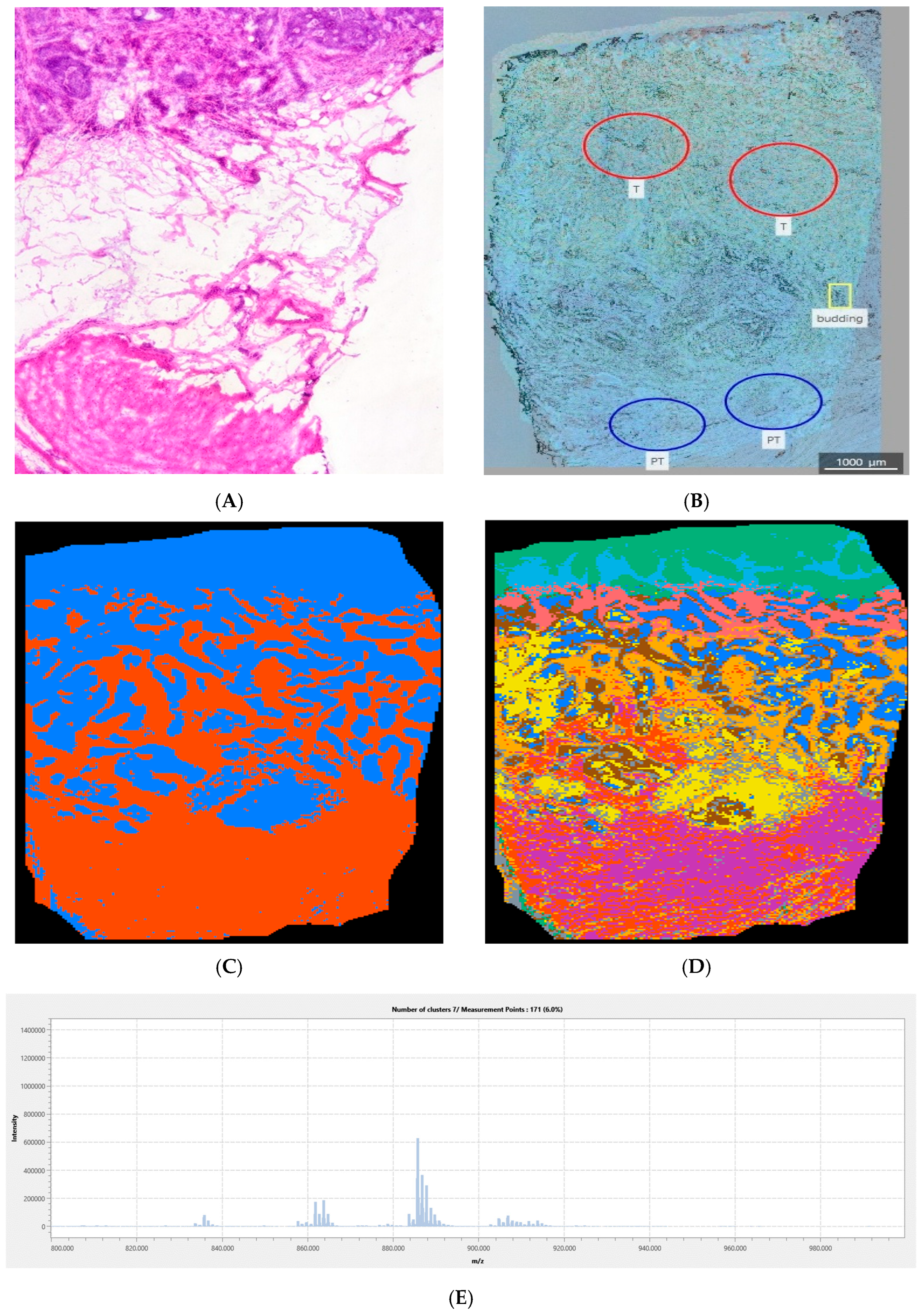

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Sample Preparation

2.2.2. Histopathology

2.2.3. Sublimation and Recrystallization of the MALDI Matrix

2.2.4. IMS Procedure

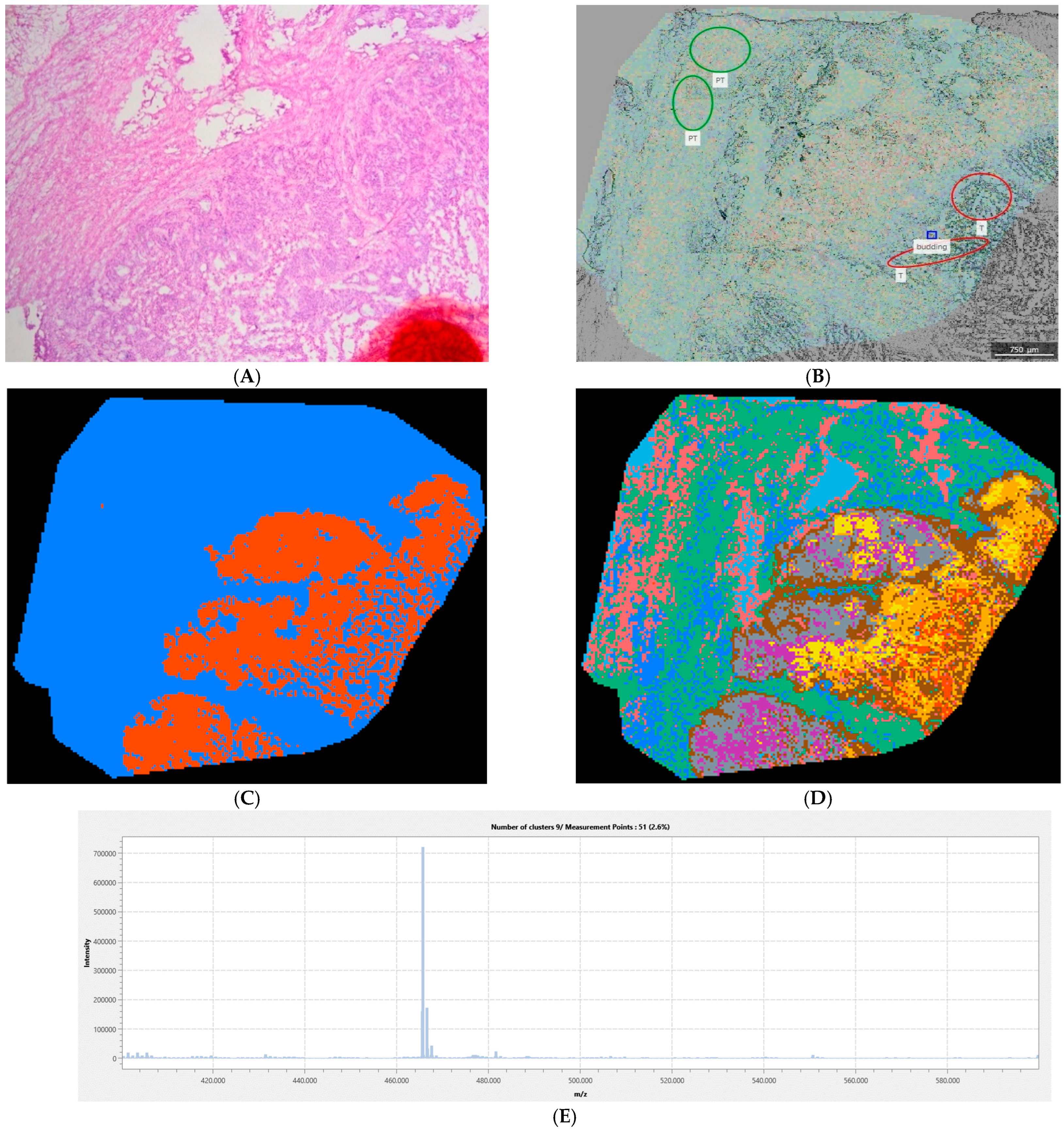

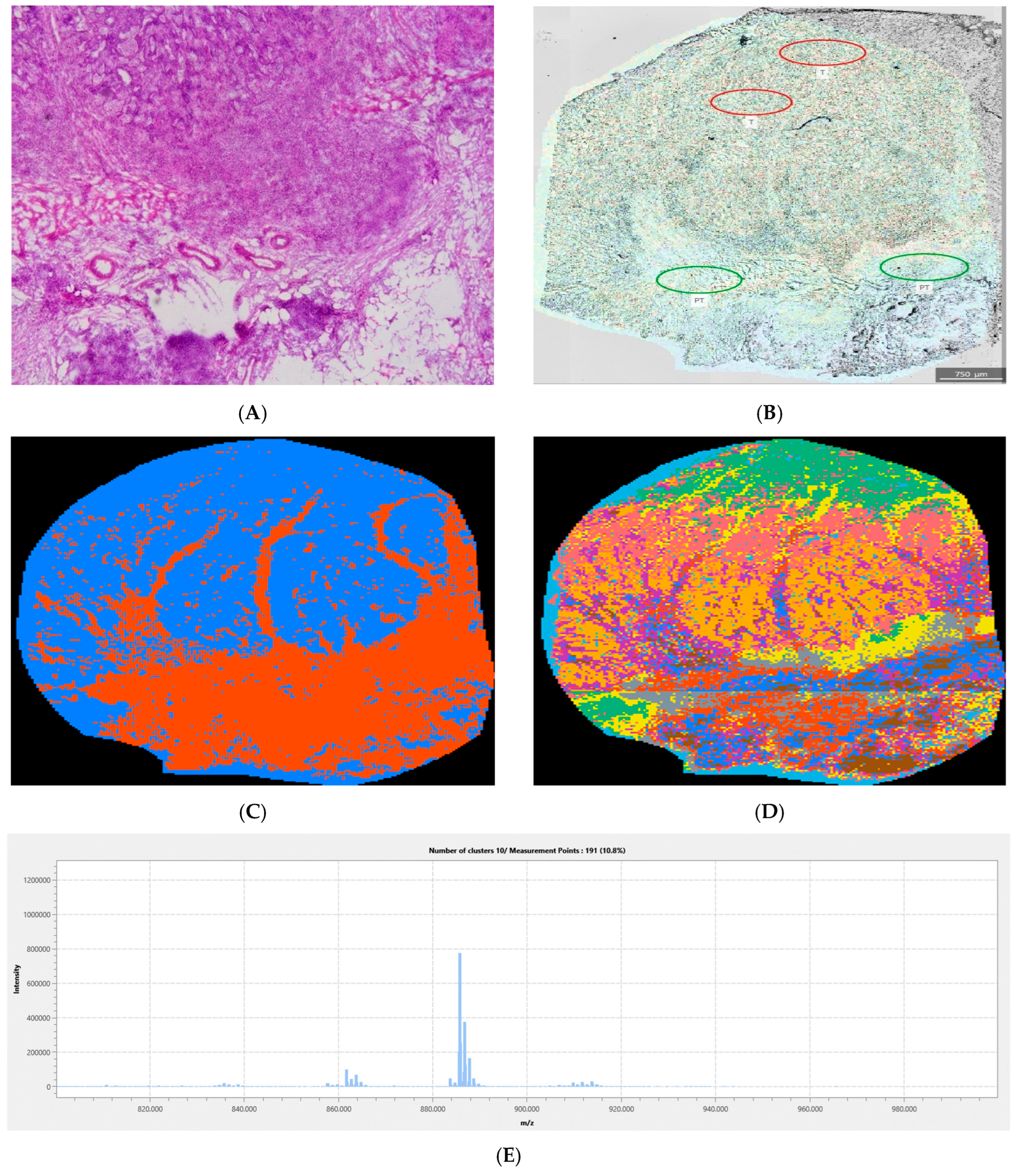

2.2.5. Image Segmentation

2.2.6. Tumor Margin and Tissue Heterogeneity Assessment

2.2.7. Statistical Analysis and Metabolite Annotation

3. Results

Quantitative Analysis of the Complete Sample Collection

4. Discussion

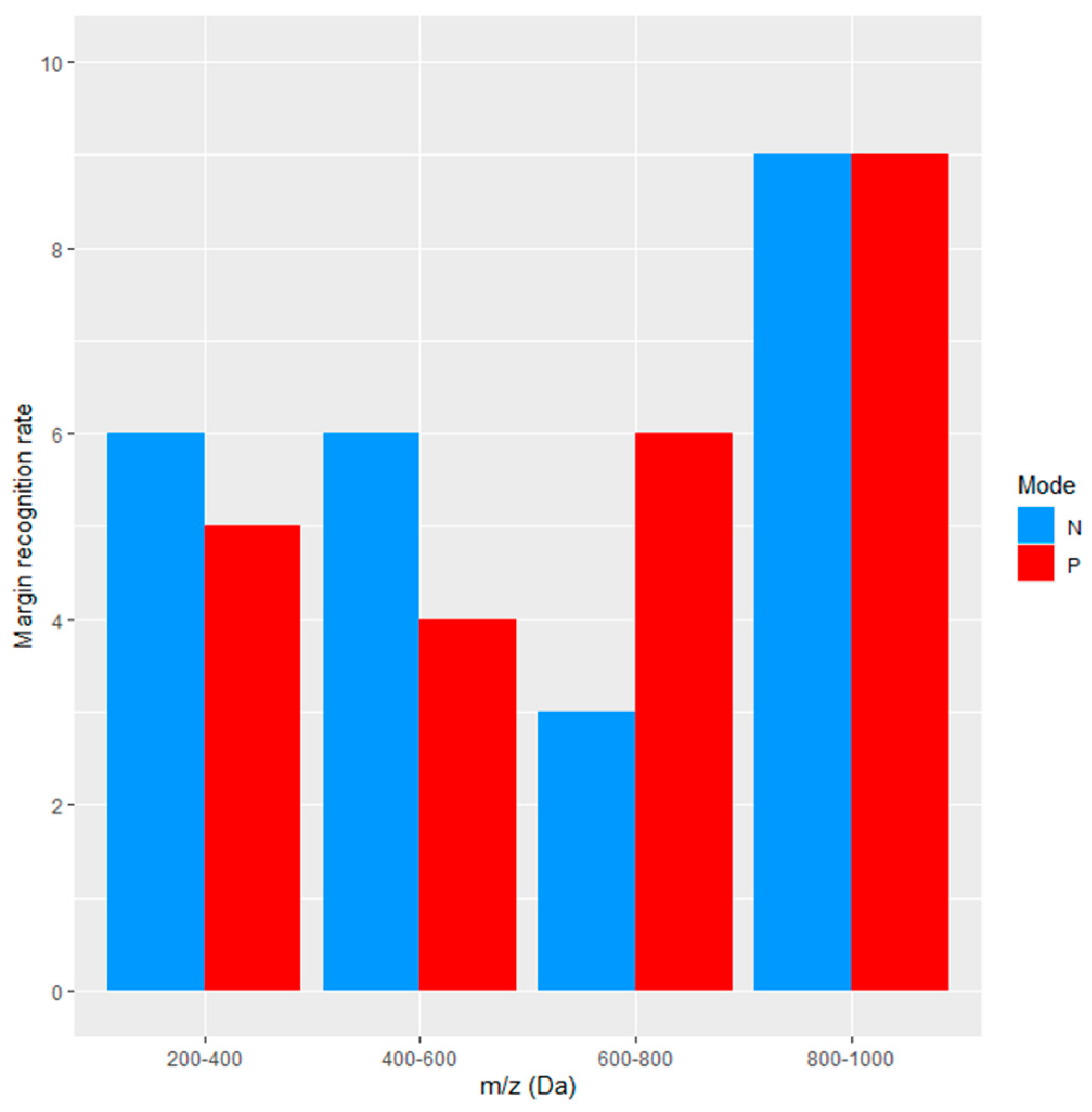

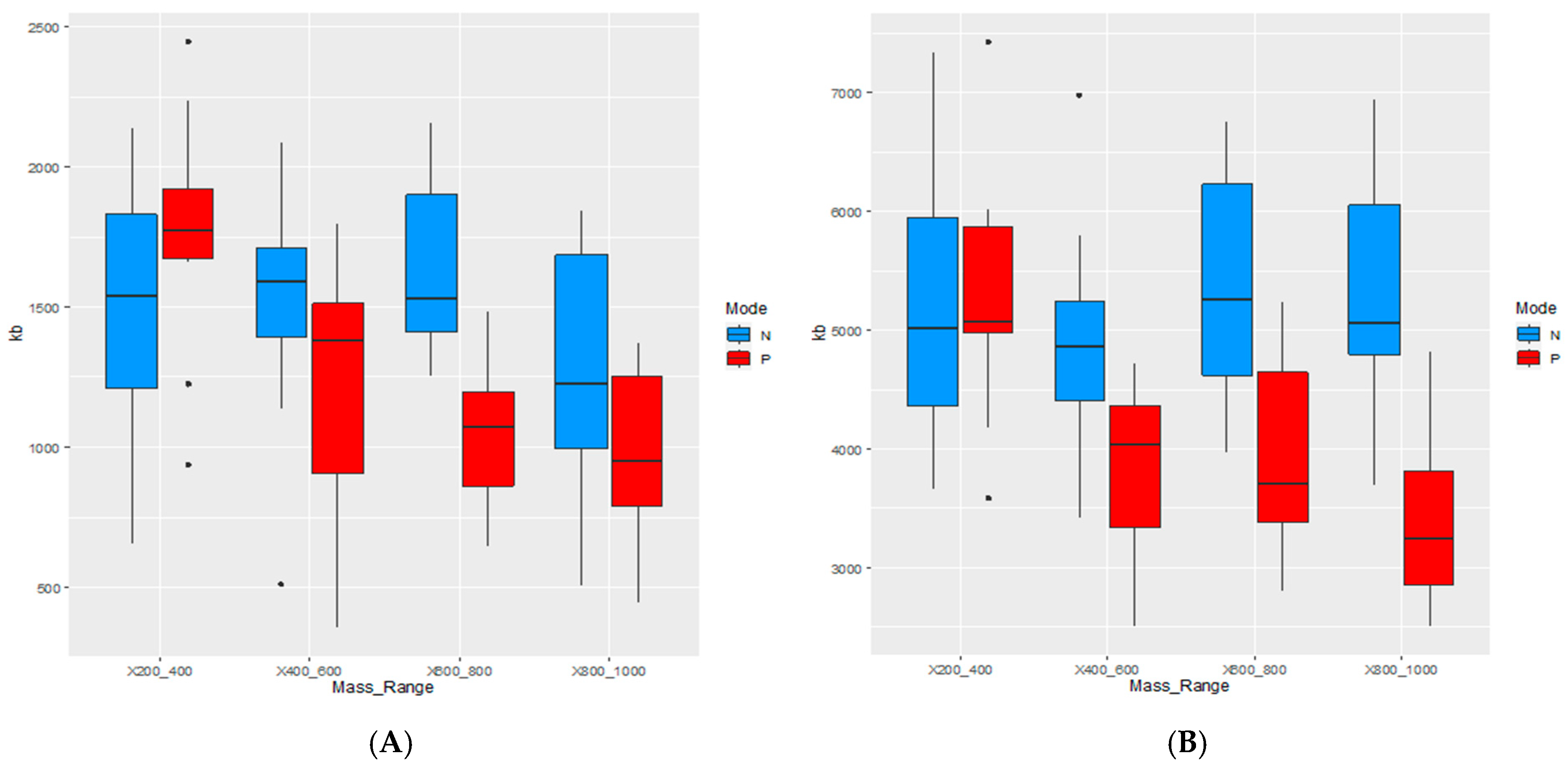

4.1. Information Content and Margin Detection Rate

4.2. Impact of Tissue Heterogeneity

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CRC | colorectal cancer |

| HE | hematoxylin-eosin |

| IMS | imaging mass spectrometry |

| MALDI TOF | matrix-associated laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight |

| UPLC-TOF-MS/MS | ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometry |

| ITO | indium-tin-oxide |

| ROI | region of interest |

| TME | tumor microenvironment |

| dCTP | deoxycytidine triphosphate |

| dCTPP1 | dCTP pyrophosphatase 1 |

| DESI-IMS | desorption electrospray ionization imaging mass spectrometry |

| SIMS | secondary-ion mass spectrometry |

References

- Hrvatski Zavod za Javno Zdravstvo. Incidencija i Mortalitet od Raka u EU-27 Zemljama za 2020. Godinu. Available online: https://www.hzjz.hr/sluzba-epidemiologija-prevencija-nezaraznih-bolesti/incidencija-i-mortalitet-od-raka-u-eu-27-zemljama-za-2020-godinu/ (accessed on 7 July 2024).

- Wu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Wei, M. Global burden of colorectal cancer in 2022 and projections to 2050: Incidence and mortality estimates from GLOBOCAN. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donato, S.; Agostino, R.G.; Peña, L.M.A.; Arfelli, F.; Brombal, L.; Longo, R.; Martellani, F.; Romano, A.; Rosano, I.; Saccomano, G.; et al. Unveiling tumor invasiveness: Enhancing cancer diagnosis with phase-contrast microtomography for 3D virtual histology. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2024, 139, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, H.; Yamashita, K.; Urabe, Y.; Kuwai, T.; Oka, S. Management of T1 Colorectal Cancer. Digestion 2025, 106, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S.S.; Regan, M.S.; Randall, E.C.; Abdelmoula, W.M.; Clark, A.R.; Lopez, B.G.-C.; Cornett, D.S.; Haase, A.; Santagata, S.; Agar, N.Y.R. Rapid MALDI mass spectrometry imaging for surgical pathology. npj Precis. Oncol. 2019, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cajal, S.R.Y.; Sesé, M.; Capdevila, C.; Aasen, T.; De Mattos-Arruda, L.; Diaz-Cano, S.J.; Hernández-Losa, J.; Castellví, J. Clinical implications of intratumor heterogeneity: Challenges and opportunities. J. Mol. Med. 2020, 98, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, R.K.; Banerjee, I.; Shivji, S.; Jain, S.; Hartman, D.; Buchanan, D.D.; Jenkins, M.A.; Schaeffer, D.F.; Rosty, C.; Como, J.; et al. Quantitative Pathologic Analysis of Digitized Images of Colorectal Carcinoma Improves Prediction of Recurrence-Free Survival. Gastroenterology 2022, 163, 1531–1546.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Fernández, F.M. Advances in mass spectrometry imaging for spatial cancer metabolomics. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2022, 43, 235–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwamborn, K.; Kriegsmann, M.; Weichert, W. MALDI imaging mass spectrometry—From bench to bedside. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Proteins Proteom. 2017, 1865, 776–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Gan, S.; Guo, B.; Yang, L. Application of clustering strategy for automatic segmentation of tissue regions in mass spectrometry imaging. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2024, 38, e9717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharti, A.; Ajinkya, K.; Andrea, M.M.; Fernanda, R.-G.; Hanibal, B.; Philipp, S.; Frauke, A.; Oliver, K. MALDI imaging combined with two-photon microscopy reveals local differences in the heterogeneity of colorectal cancer. npj Imaging 2024, 2, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, K.D.; Pětrošová, H.; Lum, J.J.; Goodlett, D.R. Mass spectrometry imaging methods for visualizing tumor heterogeneity. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2024, 86, 103068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, J.; Wan, X.; Tou, F.; He, Q.; Xiong, A.; Chen, X.; Cui, W.; Zheng, Z. Molecular Characterization of Advanced Colorectal Cancer Using Serum Proteomics and Metabolomics. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 687229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafim, P.V.P.; de Figueiredo, A.G., Jr.; Felipe, A.V.; Turco, E.G.L.; da Silva, I.D.C.G.; Forones, N.M. Study of lipid biomarkers of patients with polyps and colorectal cancer. Arq. Gastroenterol. 2019, 56, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes Gonçalves, J.P.; Bollwein, C.; Weichert, W.; Schwamborn, K. Implementation of Mass Spectrometry Imaging in Pathology. Clin. Lab. Med. 2021, 41, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, A.W.; Weljie, A.M. Metabolite Imaging at the Margin: Visualizing Metabolic Tumor Gradients Using Mass Spectrometry. Cancer Res. 2020, 80, 1231–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrell, N.; Sadeghirad, H.; Blick, T.; Bidgood, C.; Leggatt, G.R.; O’Byrne, K.; Kulasinghe, A. Metabolomics at the tumor microenvironment interface: Decoding cellular conversations. Med. Res. Rev. 2023, 44, 1121–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, Y. Driving innovations in cancer research through spatial metabolomics: A bibliometric review of trends and hotspots. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1589943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, M.B.; Greene, F.L.; Edge, S.B.; Compton, C.C.; Gershenwald, J.E.; Brookland, R.K.; Meyer, L.; Gress, D.M.; Byrd, D.R.; Winchester, D.P. The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more “personalized” approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2017, 67, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rueden, C.T.; Schindelin, J.; Hiner, M.C.; Dezonia, B.E.; Walter, A.E.; Arena, E.T.; Eliceiri, K.W. ImageJ2: ImageJ for the next generation of scientific image data. BMC Bioinform. 2017, 18, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, A.; Phapale, P.; Chernyavsky, I.; Lavigne, R.; Fay, D.; Tarasov, A.; Kovalev, V.; Fuchser, J.; Nikolenko, S.; Pineau, C.; et al. FDR-controlled metabolite annotation for high-resolution imaging mass spectrometry. Nat. Methods 2016, 14, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, E.S.; Uritboonthai, W.; Aisporna, A.; Hoang, C.; Heyman, H.M.; Connell, L.; Olivier-Jimenez, D.; Giera, M.; Siuzdak, G. METLIN-CCS Lipid Database: An authentic standards resource for lipid classification and identification. Nat. Metab. 2024, 6, 981–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiller, J.; Zschörnig, O.; Petkovic, M.; Müller, M.; Arnhold, J.; Arnold, K. Lipid analysis of human HDL and LDL by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry and 31P-NMR. J. Lipid Res. 2001, 42, 1501–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, A.E.; Giancotti, F.G.; Rustgi, A.K. Metastatic colorectal cancer: Mechanisms and emerging therapeutics. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 44, 222–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ma, X.; Chakravarti, D.; Shalapour, S.; DePinho, R.A. Genetic and biological hallmarks of colorectal cancer. Genes Dev. 2021, 35, 787–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañellas-Socias, A.; Sancho, E.; Batlle, E. Mechanisms of metastatic colorectal cancer. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 21, 609–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesely, S.L.; Dolci, C.A.; Dolci, S.R.; Vesely, A.A. Information Content of Images; AES: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, L.; Wang, X.; Guo, X.; Shi, L.; Su, S.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Tan, N.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Z. Identification of Novel Target DCTPP1 for Colorectal Cancer Therapy with the Natural Small-Molecule Inhibitors Regulating Metabolic Reprogramming. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202402543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppenheimer, S.R.; Mi, D.; Sanders, M.E.; Caprioli, R.M. Molecular Analysis of Tumor Margins by MALDI Mass Spectrometry in Renal Carcinoma. J. Proteome Res. 2010, 9, 2182–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.H.; Gami, A.J.; Desai, N.H.; Gandhi, J.S.; Trivedi, P.P. Tumor budding as a prognostic indicator in colorectal carcinoma: A retrospective study of primary colorectal carcinoma cases in a tertiary care center. Indian J. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 13, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, R.P.; Vierkant, R.A.; Tillmans, L.S.; Wang, A.H.; Laird, P.W.; Weisenberger, D.J.; Lynch, C.F.; French, A.J.; Slager, S.L.; Raissian, Y.; et al. Tumor budding in colorectal carcinoma: Confirmation of prognostic significance and histologic cutoff in a population-based cohort. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2015, 39, 1340–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.J.; Kakar, S. Tumor budding in colorectal carcinoma: Translating a morphologic score into clinically meaningful results. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2018, 142, 952–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugli, A.; Kirsch, R.; Ajioka, Y.; Bosman, F.; Cathomas, G.; Dawson, H.; El Zimaity, H.; Fléjou, J.F.; Hansen, T.P.; Hartmann, A.; et al. Recommendations for reporting tumor budding in colorectal cancer based on the International Tumor Budding Consensus Conference (ITBCC) 2016. Mod. Pathol. 2017, 30, 1299–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rödel, C.; Fokas, E.; Gani, C. Complete response after chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer: What is the reasonable approach? Innov. Surg. Sci. 2017, 3, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Trogrlić, B.; Bednjanić, A.; Kovačić, B.; Požgain, Z.; Mandić, D.; Kratofil, M.; Rajc, J.; Debeljak, Ž.; Tomaš, I. Assessment of Tumor Margin and Heterogeneity of Colorectal Cancer Using Imaging Mass Spectrometry and Image Segmentation. Cancers 2026, 18, 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010169

Trogrlić B, Bednjanić A, Kovačić B, Požgain Z, Mandić D, Kratofil M, Rajc J, Debeljak Ž, Tomaš I. Assessment of Tumor Margin and Heterogeneity of Colorectal Cancer Using Imaging Mass Spectrometry and Image Segmentation. Cancers. 2026; 18(1):169. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010169

Chicago/Turabian StyleTrogrlić, Bojan, Ana Bednjanić, Borna Kovačić, Zrinka Požgain, Dario Mandić, Magdalena Kratofil, Jasmina Rajc, Željko Debeljak, and Ilijan Tomaš. 2026. "Assessment of Tumor Margin and Heterogeneity of Colorectal Cancer Using Imaging Mass Spectrometry and Image Segmentation" Cancers 18, no. 1: 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010169

APA StyleTrogrlić, B., Bednjanić, A., Kovačić, B., Požgain, Z., Mandić, D., Kratofil, M., Rajc, J., Debeljak, Ž., & Tomaš, I. (2026). Assessment of Tumor Margin and Heterogeneity of Colorectal Cancer Using Imaging Mass Spectrometry and Image Segmentation. Cancers, 18(1), 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010169