Targeting Glutamine Transporters as a Novel Drug Therapy for Synovial Sarcoma

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

2.2. CCK8 Assay

2.3. Apoptosis Assay

2.4. Western Blotting Analysis

2.5. In Vivo Experiment

2.6. Immunohistochemical Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

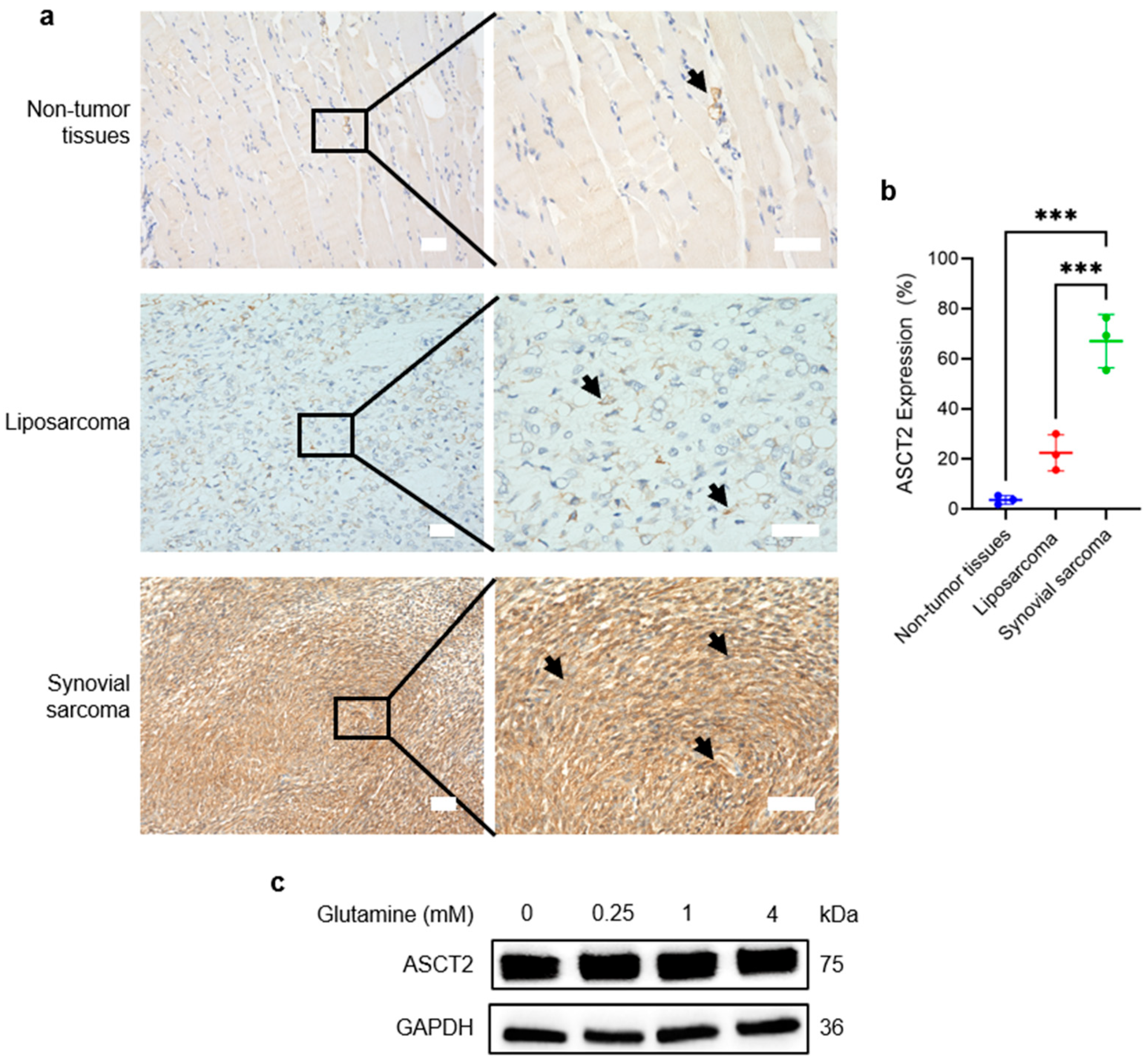

3.1. ASCT2 Is Highly Expressed and Constitutive in SS

3.2. SS Cells Exhibit High Glutamine Demand for Proliferation

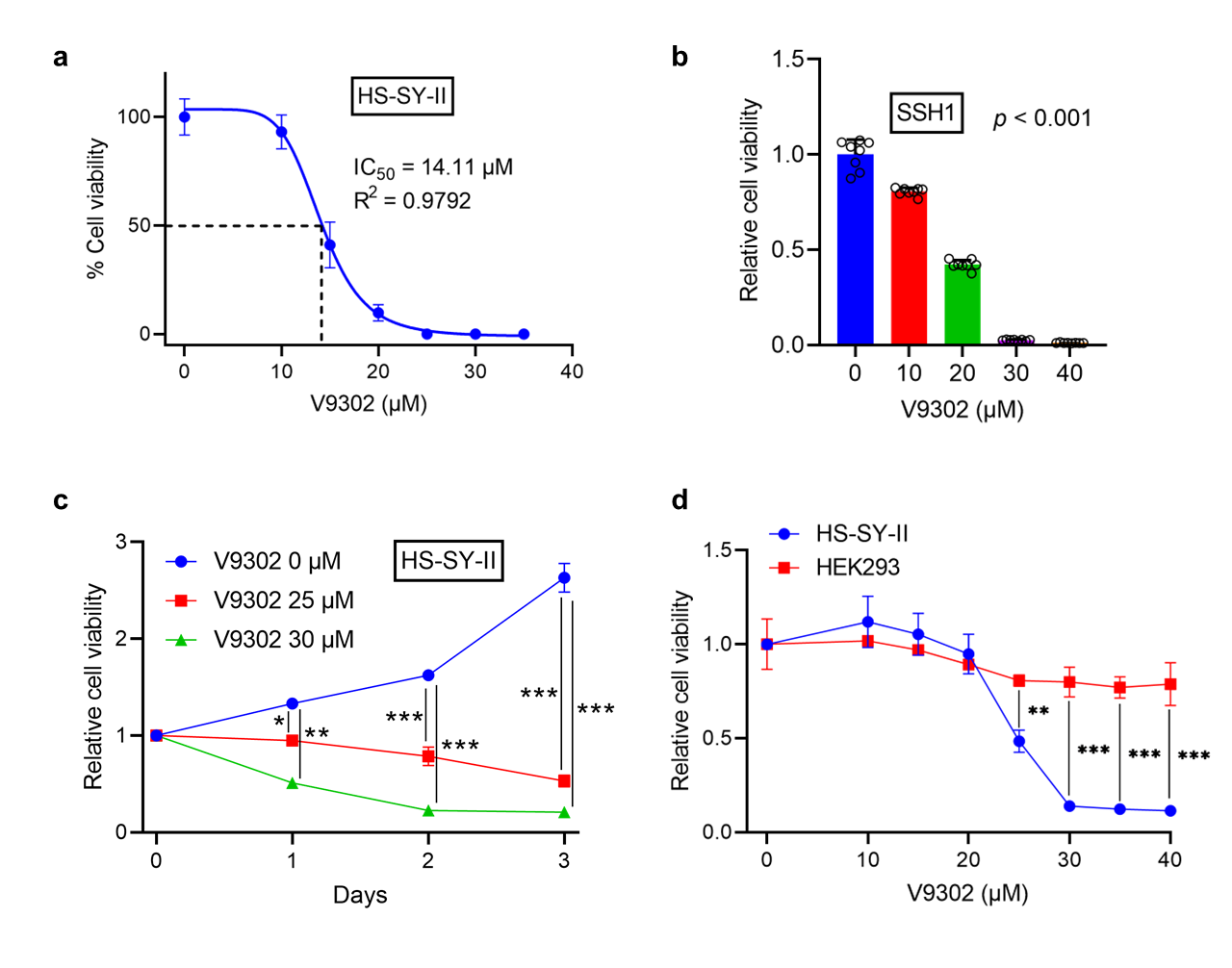

3.3. V9302 Suppresses Cell Viability in SS While Sparing Normal Cells

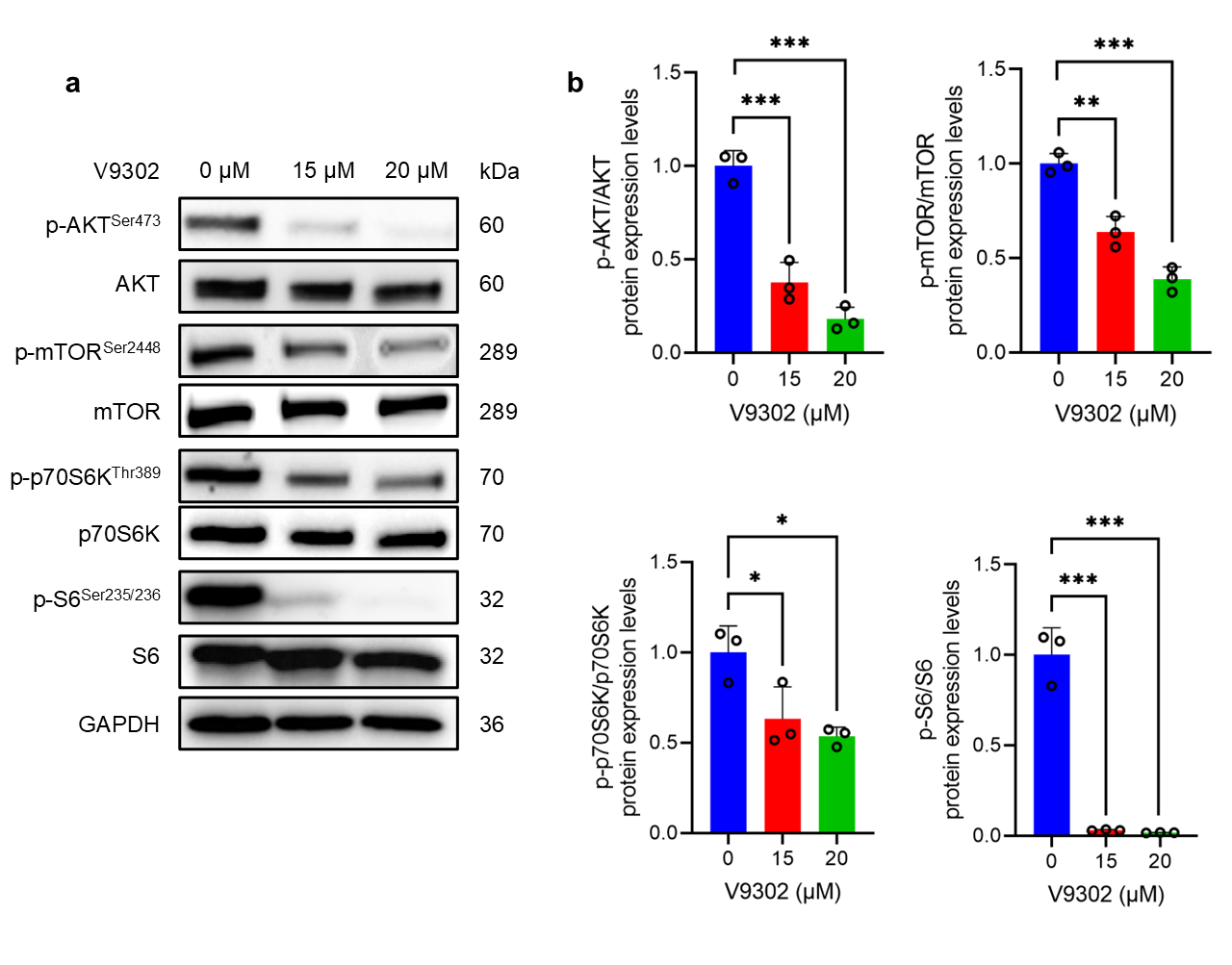

3.4. V9302 Suppresses the AKT/mTOR Signaling Pathway

3.5. V9302 Induces Apoptosis in SS but Not in Normal Cells

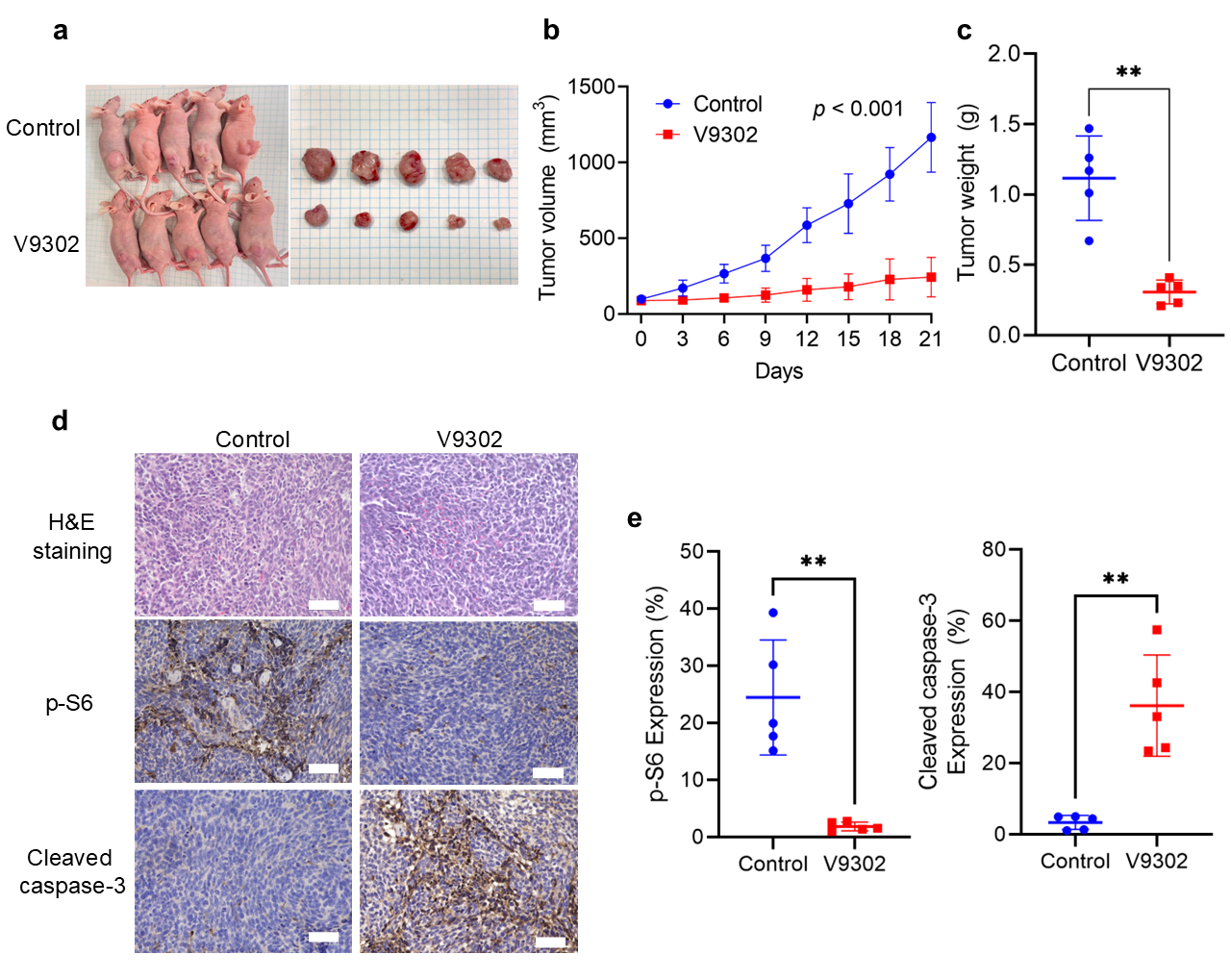

3.6. V9302 Inhibits Tumor Growth in the SS Xenograft Model by Modulating mTOR and Apoptosis Signaling

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SS | Synovial sarcoma |

| UPS | Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s medium |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| SSH1 | patient-derived primary SS cells |

| IC50 | 50% inhibitory concentration |

| DMSO | dimethyl sulfoxide |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| LPS | Liposarcoma |

| p-S6 | Phospho-S6 ribosomal protein |

References

- Riedel, R.F.; Jones, R.L.; Italiano, A.; Bohac, C.; Thompson, J.C.; Mueller, K.; Khan, Z.; Pollack, S.M.; Van Tine, B.A. Systemic Anti-Cancer Therapy in Synovial Sarcoma: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2018, 10, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazendam, A.M.; Popovic, S.; Munir, S.; Parasu, N.; Wilson, D.; Ghert, M. Synovial Sarcoma: A Clinical Review. Curr. Oncol. 2021, 28, 1909–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.; De Salvo, G.L.; Brennan, B.; van Noesel, M.M.; De Paoli, A.; Casanova, M.; Francotte, N.; Kelsey, A.; Alaggio, R.; Oberlin, O.; et al. Synovial Sarcoma in Children and Adolescents: The European Pediatric Soft Tissue Sarcoma Study Group Prospective Trial (EpSSG NRSTS 2005). Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blay, J.-Y.; Mehren, M.v.; Jones, R.L.; Martin-Broto, J.; Stacchiotti, S.; Bauer, S.; Gelderblom, H.; Orbach, D.; Hindi, N.; Tos, A.D.; et al. Synovial Sarcoma: Characteristics, Challenges, and Evolving Therapeutic Strategies. ESMO Open 2023, 8, 101618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baoleri, X.; Dong, C.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, X.; Xie, P.; Li, Y. Combination of L-Gossypol and Low-Concentration Doxorubicin Induces Apoptosis in Human Synovial Sarcoma Cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 12, 5924–5932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Byun, J.-K.; Choi, Y.-K.; Park, K.-G. Targeting Glutamine Metabolism as a Therapeutic Strategy for Cancer. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X.-D.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Wei, Y.-C.; Han, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Z.-R.; Li, Z.-Z.; Jiang, J.-W.; et al. A Novel ASCT2 Inhibitor, C118P, Blocks Glutamine Transport and Exhibits Antitumour Efficacy in Breast Cancer. Cancers 2023, 15, 5082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, R.; Shuai, Y.; Huang, Y.; Jin, R.; Wang, X.; Luo, J. ASCT2 (SLC1A5)-Dependent Glutamine Uptake Is Involved in the Progression of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 2020, 122, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.; Malik, D.; Perkons, N.; Huangyang, P.; Khare, S.; Rhoades, S.; Gong, Y.-Y.; Burrows, M.; Finan, J.M.; Nissim, I.; et al. Targeting Glutamine Metabolism Slows Soft Tissue Sarcoma Growth. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, N.; Cross, A.M.; Lorenzi, P.L.; Khan, J.; Gryder, B.E.; Kim, S.; Caplen, N.J. EWS-FLI1 Reprograms the Metabolism of Ewing Sarcoma Cells via Positive Regulation of Glutamine Import and Serine-glycine Biosynthesis. Mol. Carcinog. 2018, 57, 1342–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterse, E.F.P.; Niessen, B.; Addie, R.D.; de Jong, Y.; Cleven, A.H.G.; Kruisselbrink, A.B.; van den Akker, B.E.W.M.; Molenaar, R.J.; Cleton-Jansen, A.-M.; Bovée, J.V.M.G. Targeting Glutaminolysis in Chondrosarcoma in Context of the IDH1/2 Mutation. Br. J. Cancer 2018, 118, 1074–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.; Cooper, D.E.; Kadakia, K.T.; Allen, A.; Duan, L.; Luo, L.; Williams, N.T.; Liu, X.; Locasale, J.W.; Kirsch, D.G. Targeting Glutamine Metabolism Improves Sarcoma Response to Radiation Therapy in Vivo. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, W.; Han, Z.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Q. Targeting Glutamine Metabolism as a Potential Target for Cancer Treatment. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 44, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, T.; Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Yuan, S.; Sun, L. The Role of ASCT2 in Cancer: A Review. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 837, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, J.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, L.; Sang, S.; Xue, J. Synergistic Effect of Drug Delivery System Combining DOX and V9302 on Gastric Cancer Cells. ChemistrySelect 2022, 7, e202202187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, M.L.; Fu, A.; Zhao, P.; Li, J.; Geng, L.; Smith, S.T.; Kondo, J.; Coffey, R.J.; Johnson, M.O.; Rathmell, J.C.; et al. Pharmacological Blockade of ASCT2-Dependent Glutamine Transport Leads To Anti-Tumor Efficacy in Preclinical Models. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Hardie, R.-A.; Hoy, A.J.; van Geldermalsen, M.; Gao, D.; Fazli, L.; Sadowski, M.C.; Balaban, S.; Schreuder, M.; Nagarajah, R.; et al. Targeting ASCT2-Mediated Glutamine Uptake Blocks Prostate Cancer Growth and Tumour Development. J. Pathol. 2015, 236, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhong, X.; Yao, W.; Yu, J.; Wang, C.; Li, Z.; Lai, S.; Qu, F.; Fu, X.; Huang, X.; et al. Inhibitor of Glutamine Metabolism V9302 Promotes ROS-Induced Autophagic Degradation of B7H3 to Enhance Antitumor Immunity. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 101753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, M.L.; Khodadadi, A.B.; Cuthbertson, M.L.; Smith, J.A.; Manning, H.C. 2-Amino-4-Bis(Aryloxybenzyl)Aminobutanoic Acids: A Novel Scaffold for Inhibition of ASCT2-Mediated Glutamine Transport. Bioorg Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 1044–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonobe, H.; Manabe, Y.; Furihata, M.; Iwata, J.; Oka, T.; Ohtsuki, Y.; Mizobuchi, H.; Yamamoto, H.; Kumano, O.; Abe, S. Establishment and Characterization of a New Human Synovial Sarcoma Cell Line, HS-SY-II. Lab. Invest. 1992, 67, 498–505. [Google Scholar]

- Jerby-Arnon, L. Opposing Immune and Genetic Mechanisms Shape Oncogenic Programs in Synovial Sarcoma. Available online: https://singlecell.broadinstitute.org/single_cell/study/SCP167/synovial-sarcoma?genes=SLC1A5 (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Ponder, K.G.; Boise, L.H. The Prodomain of Caspase-3 Regulates Its Own Removal and Caspase Activation. Cell Death Discov. 2019, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanein, M.; Hoeksema, M.D.; Shiota, M.; Qian, J.; Harris, B.K.; Chen, H.; Clark, J.E.; Alborn, W.E.; Eisenberg, R.; Massion, P.P. SLC1A5 Mediates Glutamine Transport Required for Lung Cancer Cell Growth and Survival. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 560–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Wu, J.; Zhou, M.; Wu, J.; Wu, Z.; Lin, L.; Huang, N.; Liao, W.; Sun, L. Inhibition of Glutamine Uptake Improves the Efficacy of Cetuximab on Gastric Cancer. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2021, 20, 15347354211045349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhove, K.; Derveaux, E.; Graulus, G.-J.; Mesotten, L.; Thomeer, M.; Noben, J.-P.; Guedens, W.; Adriaensens, P. Glutamine Addiction and Therapeutic Strategies in Lung Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Peng, X.; Li, Y.; Wei, S.; He, G.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Yang, S.; Li, D.; Lin, W.; et al. Glutamine Addiction in Tumor Cell: Oncogene Regulation and Clinical Treatment. Cell Commun. Signal 2024, 22, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmick, N.; Posadas, E.; Ellis, L.; Freedland, S.J.; Di Vizio, D.; Freeman, M.R.; Theodorescu, D.; Figlin, R.; Gong, J. Targeting Glutamine Metabolism in Prostate Cancer. Front. Biosci. (Elite Ed.) 2023, 15, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bröer, A.; Fairweather, S.; Bröer, S. Disruption of Amino Acid Homeostasis by Novel ASCT2 Inhibitors Involves Multiple Targets. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulte, M.L.; Dawson, E.S.; Saleh, S.A.; Cuthbertson, M.L.; Manning, H.C. 2-Substituted Nγ-Glutamylanilides as Novel Probes of ASCT2 with Improved Potency. Bioorg Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 25, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, H.C.; Yu, Y.C.; Sung, Y.; Han, J.M. Glutamine Reliance in Cell Metabolism. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52, 1496–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, D.; Wang, S.; Yu, P.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Y.; Meng, X.; Li, J.; Xiang, L. Baicalein Induces Apoptosis by Inhibiting the Glutamine-mTOR Metabolic Pathway in Lung Cancer. J. Adv. Res. 2024, 68, 341–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, K.E.; Rojo, F.; She, Q.-B.; Solit, D.; Mills, G.B.; Smith, D.; Lane, H.; Hofmann, F.; Hicklin, D.J.; Ludwig, D.L. mTOR Inhibition Induces Upstream Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Signaling and Activates Akt. Cancer Res 2006, 66, 1500–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Geldermalsen, M.; Wang, Q.; Nagarajah, R.; Marshall, A.D.; Thoeng, A.; Gao, D.; Ritchie, W.; Feng, Y.; Bailey, C.G.; Deng, N.; et al. ASCT2/SLC1A5 Controls Glutamine Uptake and Tumour Growth in Triple-Negative Basal-like Breast Cancer. Oncogene 2016, 35, 3201–3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byun, J.-K.; Park, M.; Lee, S.; Yun, J.W.; Lee, J.; Kim, J.S.; Cho, S.J.; Jeon, H.-J.; Lee, I.-K.; Choi, Y.-K.; et al. Inhibition of Glutamine Utilization Synergizes with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor to Promote Antitumor Immunity. Mol. Cell 2020, 80, 592–606.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Antibody | Company | Dilution | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-phospho-AKT | Cell Signaling (#9271) | 1/1000 | WB |

| Anti-AKT | Cell Signaling (#9272) | 1/1000 | WB |

| Anti-phospho-mTOR | Cell Signaling (5536T) | 1/1000 | WB |

| Anti-mTOR | Cell Signaling (#2972) | 1/1000 | WB |

| Anti-phospho-p70S6K | Cell Signaling (#9205) | 1/1000 | WB |

| Anti-p70S6K | Cell Signaling (#9202) | 1/1000 | WB |

| Anti-phospho-S6 | Cell Signaling (#2211) | 1/1000 | WB, IHC |

| Anti-S6 | Cell Signaling (2217T) | 1/1000 | WB |

| Anti-cleaved caspase-3 | Cell Signaling (#9664) | 1/1000 | WB, IHC |

| Anti–caspase-3 | Cell Signaling (#9662) | 1/1000 | WB |

| Anti-GAPDH | Millipore (MAB374) | 1/10.000 | WB |

| SLC1A5/ASCT2 Antibody | Proteintech (20350-1-AP) | 1/400 | WB, IHC |

| Code | Age | Gender | Site | Pathology | Fusion Gene | Chemotherapy | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSH1 | 28 | Male | Thigh | Monophasic synovial sarcoma | SYT-SSX 1.2.4 | Doxorubicin + Ifosfamide | CDF |

| SSH2 | 47 | Male | Thigh | Biphasic synovial sarcoma | SYX-SST+ | Doxorubicin + Ifosfamide | DOD |

| SSH3 | 52 | Female | Foot | Monophasic synovial sarcoma | SS18+ | Doxorubicin + Ifosfamide | CDF |

| LPS1 | 89 | Male | Thigh | Dedifferentiated liposarcoma | No | DOD | |

| LPS2 | 48 | Male | Thigh | Myxoid liposarcoma | No | DOD | |

| LPS3 | 63 | Female | Thigh | Myxoid liposarcoma | No | CDF |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Thanh, T.D.; Takada, N.; Yao, H.; Ban, Y.; Oebisu, N.; Hoshi, M.; Sang, N.T.Q.; Khanh, N.V.; Quang, D.M.; Thuy, L.T.T.; et al. Targeting Glutamine Transporters as a Novel Drug Therapy for Synovial Sarcoma. Cancers 2026, 18, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010015

Thanh TD, Takada N, Yao H, Ban Y, Oebisu N, Hoshi M, Sang NTQ, Khanh NV, Quang DM, Thuy LTT, et al. Targeting Glutamine Transporters as a Novel Drug Therapy for Synovial Sarcoma. Cancers. 2026; 18(1):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010015

Chicago/Turabian StyleThanh, Tran Duc, Naoki Takada, Hana Yao, Yoshitaka Ban, Naoto Oebisu, Manabu Hoshi, Nguyen Tran Quang Sang, Nguyen Van Khanh, Dang Minh Quang, Le Thi Thanh Thuy, and et al. 2026. "Targeting Glutamine Transporters as a Novel Drug Therapy for Synovial Sarcoma" Cancers 18, no. 1: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010015

APA StyleThanh, T. D., Takada, N., Yao, H., Ban, Y., Oebisu, N., Hoshi, M., Sang, N. T. Q., Khanh, N. V., Quang, D. M., Thuy, L. T. T., Dung, T. T., & Terai, H. (2026). Targeting Glutamine Transporters as a Novel Drug Therapy for Synovial Sarcoma. Cancers, 18(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010015