Disparities in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) by Age, Sex, and Race: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor (ICI) Trials

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Bias Assessment

3. Results

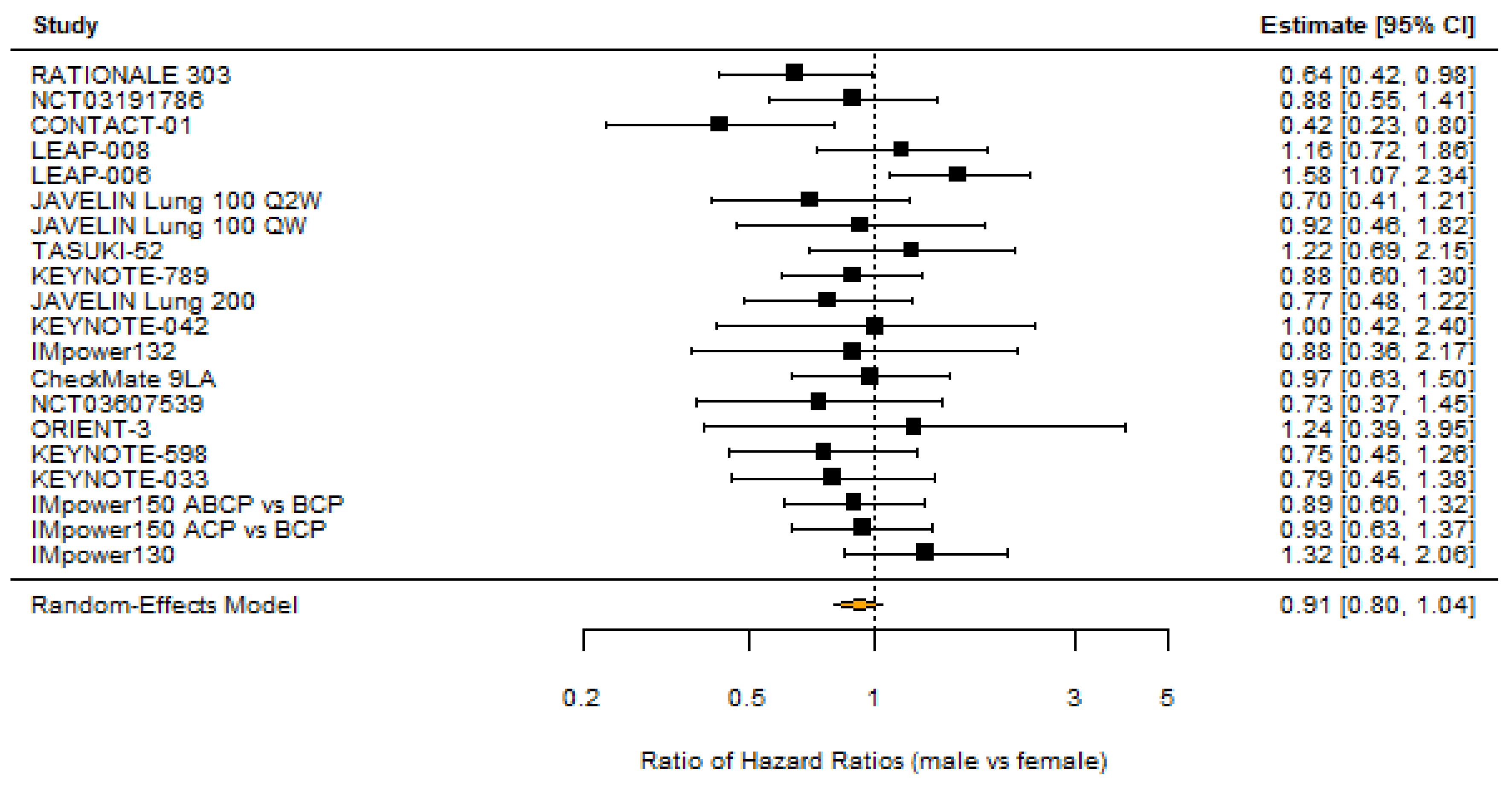

3.1. Sex

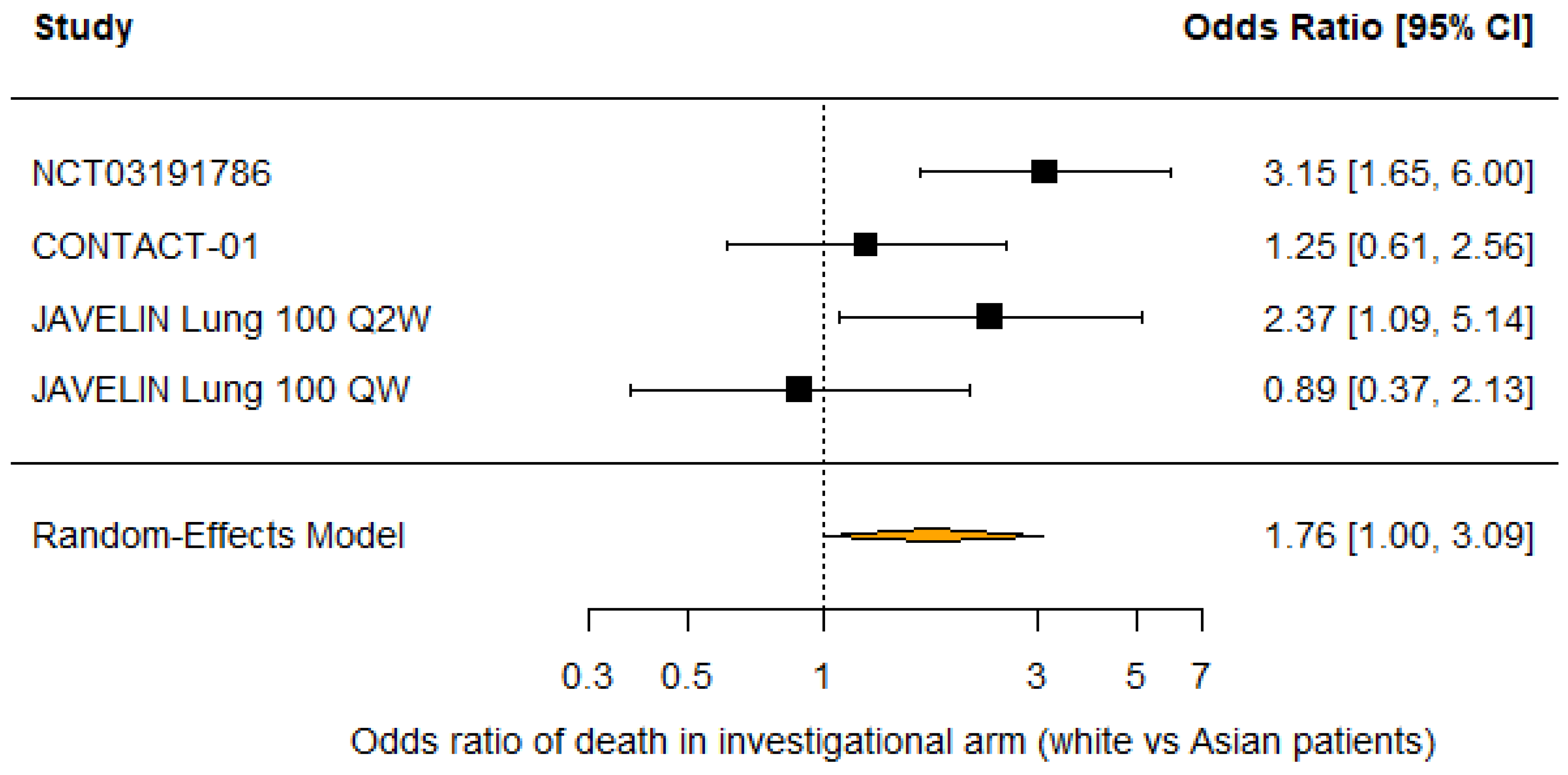

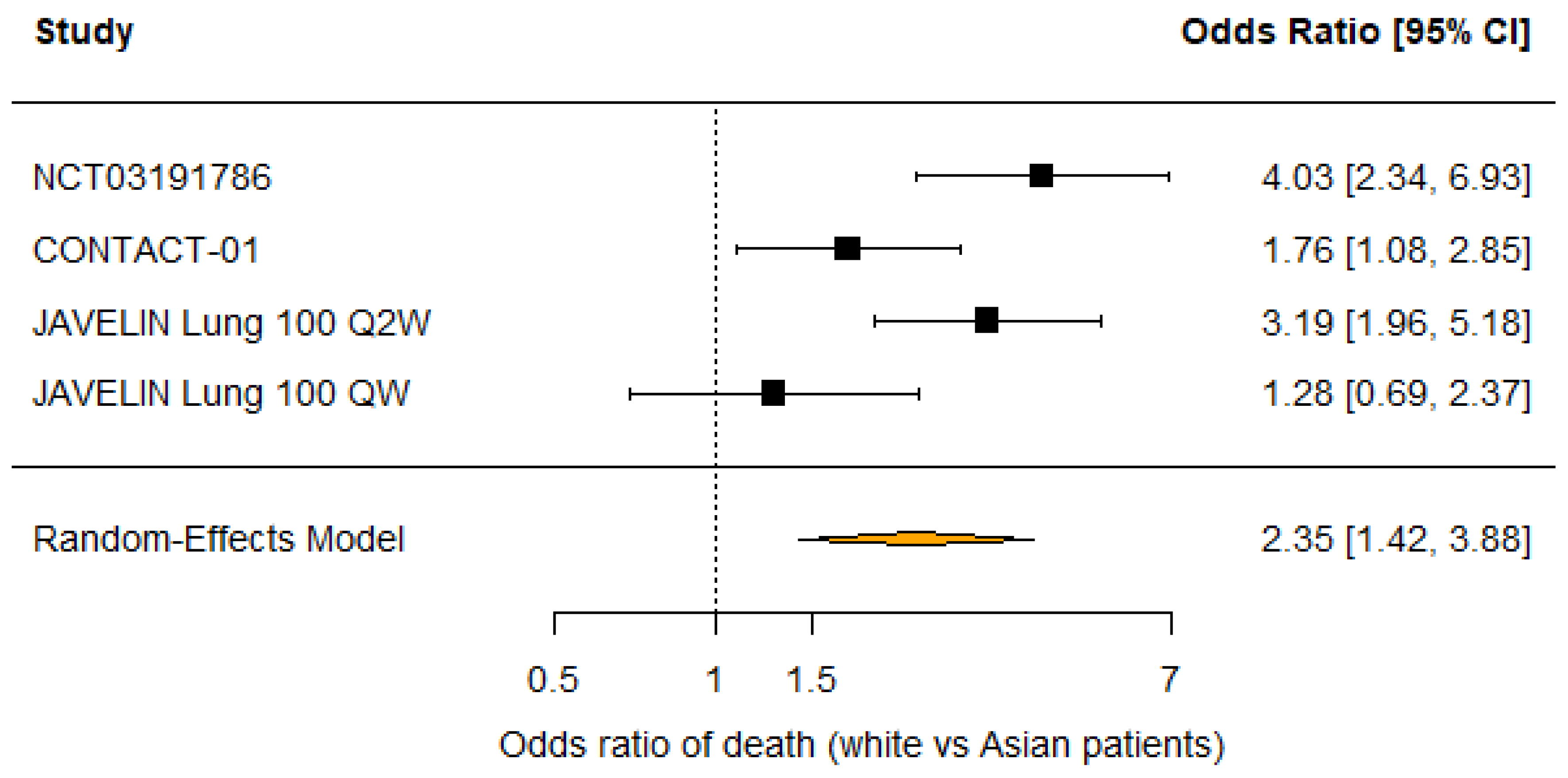

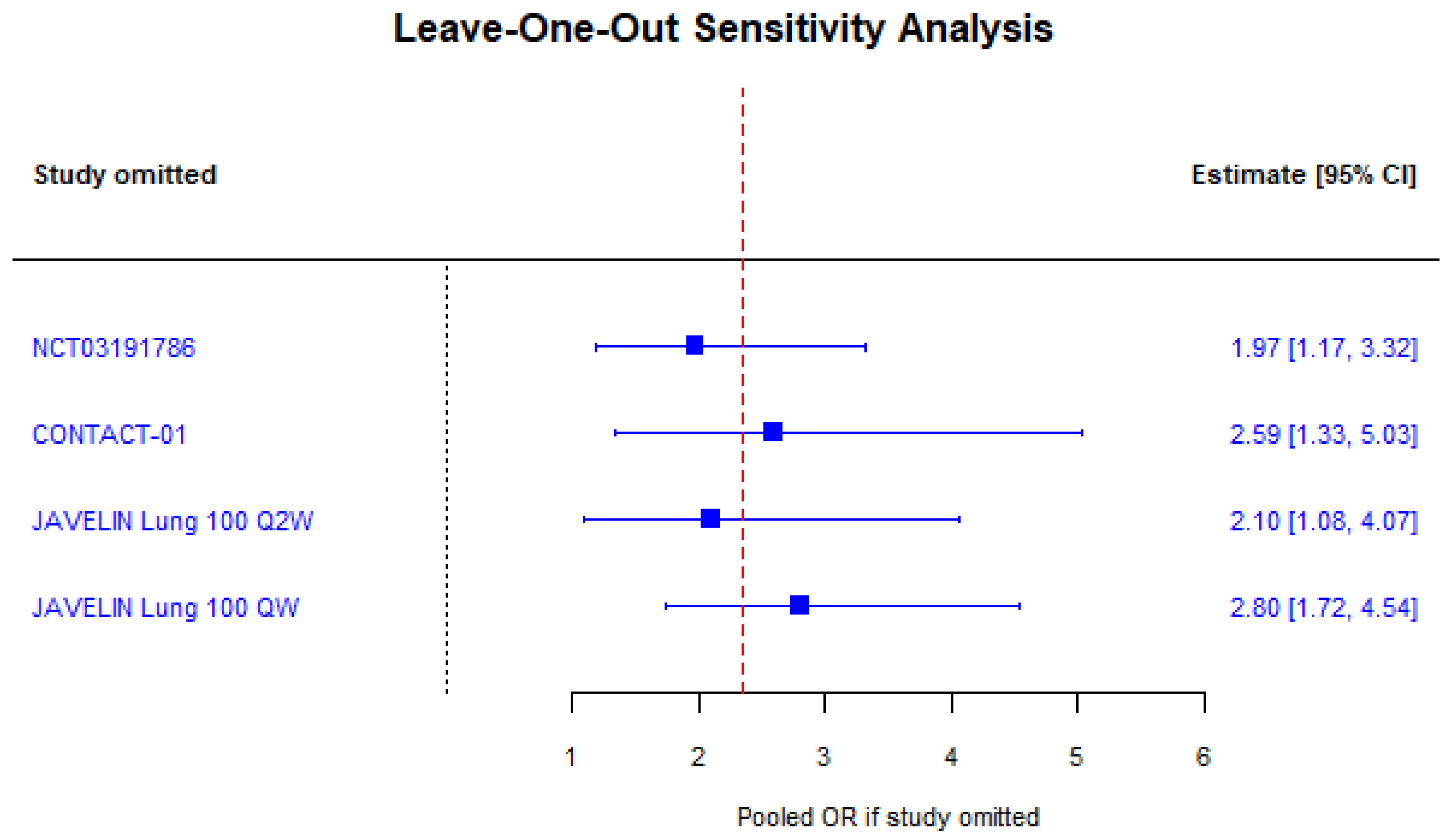

3.2. Race

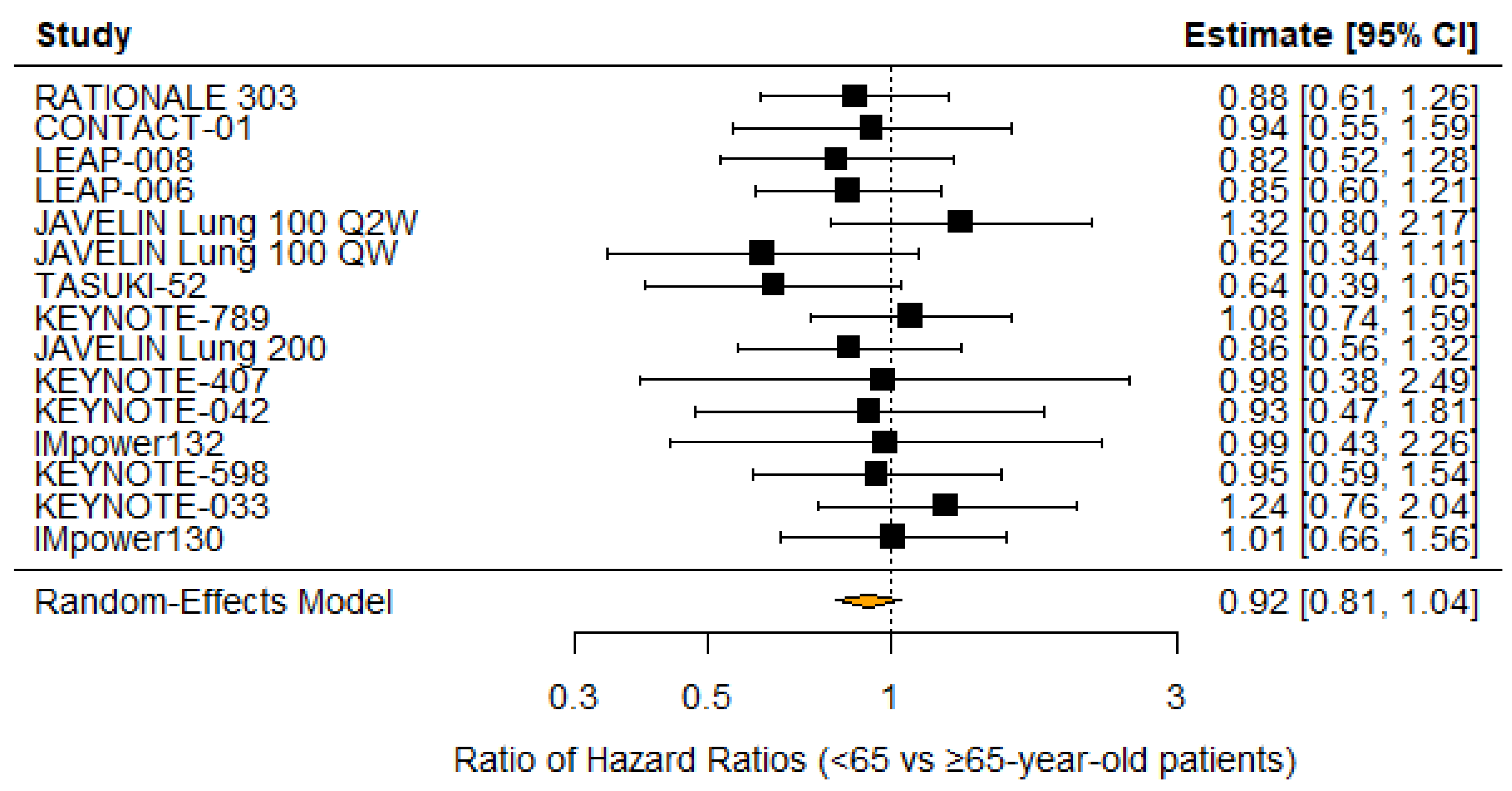

3.3. Age

4. Discussion

4.1. Disparity in Survival by Sex

4.2. Disparity in Survival by Race

4.3. Disparity in Survival by Age

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Xie, J.; Chen, M.; Liu, H.; Zhan, P.; Lv, T.; Song, Y. The Predictive Value of Clinical and Molecular Characteristics or Immunotherapy in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 732214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thandra, K.C.; Barsouk, A.A.; Saginala, K.; Aluru, J.S.; Barsouk, A. Epidemiology of lung cancer. Contemp. Oncol. 2021, 25, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girigoswami, A.; Girigoswami, K. Potential Applications of Nanoparticles in Improving the Outcome of Lung Cancer Treatment. Genes 2023, 14, 1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siciliano, M.A.; d’Apolito, M.; Del Giudice, T.; Caridà, G.; Grillone, F.; Porzio, G.; Giusti, R.; Tassone, P.; Barbieri, V.; Tagliaferri, P. Do age and performance status matter? A systematic review and network meta-analysis of immunotherapy studies in untreated advanced/metastatic non-oncogene addicted NSCLC. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1635056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Lei, S.; Wang, L.; Tang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liao, Y.; Deng, X.; Li, Y.; Gong, Y.; Li, Y. Age-related efficacy of immunotherapies in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Lung Cancer 2024, 195, 107925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Corral-Morales, J.; Ayala-de Miguel, C.; Quintana-Cortés, L.; Sánchez-Vegas, A.; Aranda-Bellido, F.; González-Santiago, S.; Fuentes-Pradera, J.; Miguel, P.A.-D. Real-world data on immune-checkpoint inhibitors in elderly patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: A retrospective study. Cancers 2025, 17, 2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.M.; Wang, Y.; Sun, X.X.; Chen, J.; Gong, Z.-P.; Meng, H.-Y. Clinical efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in older non-small-cell lung cancer patients: A meta-analysis. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 558454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Markovic, S.N.; Molina, J.R.; Halfdanarson, T.R.; Pagliaro, L.C.; Chintakuntlawar, A.V.; Li, R.; Wei, J.; Wang, L.; Liu, B.; et al. Association of sex, age, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status with survival benefit of cancer immunotherapy in randomized clinical trials: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open. 2020, 3, e2012534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conforti, F.; Pala, L.; Bagnardi, V.; Viale, G.; De Pas, T.; Pagan, E.; Pennacchioli, E.; Cocorocchio, E.; Ferrucci, P.F.; De Marinis, F.; et al. Sex-based heterogeneity in response to lung cancer immunotherapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2019, 111, 772–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.; Zheng, S.; Dong, H.; Lu, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Cui, H. Association between efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors and sex: An updated meta-analysis on 21 trials and 12,675 non-small cell lung cancer patients. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 627016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madala, S.; Rasul, R.; Singla, K.; Sison, C.; Seetharamu, N.; Castellanos, M. Gender differences and their effects on survival outcomes in lung cancer patients treated with PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 34, 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, M. Sex-differential responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors across the disease continuum unified by tumor mutational burden. Semin. Oncol. 2025, 52, 152414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Salomonsen, R.; Tattersfield, R.; Wang, A.; Cai, L.; Sadow, S.; Peters, S. Assessment of sociodemographic disparities in outcomes among patients with metastatic NSCLC receiving select immuno-oncology regimens: CORRELATE. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 9055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, R.K.; Aiello, M.; Maldonado, L.M.; Clark, T.Y.; Buchwald, Z.S.; Chang, A. Impact of race, ethnicity, and social determinants on outcomes following immune checkpoint therapy. J. Immunother. Cancer 2024, 12, e010116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers, K.L.; Mullaney, T.; Zhou, X.; Liu, J.J.; Lee, K.; Ma, M.; Jones, S.; Li, L.; Redfern, A.; Jappe, W.; et al. Analysis of real-world data to investigate the impact of race and ethnicity on response to programmed cell death-1 and programmed cell death-ligand 1 inhibitors in advanced non-small cell lung cancers. Oncologist 2021, 26, e1226–e1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genova, C.; Cappuzzo, F.; Minotti, G.; Normanno, N.; Rodgers-Gray, B.; Waghorne, N.; Novello, S.; Tiseo, M. The effects of race on anti–PD-(L)1 monoclonal antibodies in non-small cell lung cancer: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2025, 214, 104812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Qin, B.D.; Xiao, K.; Xu, S.; Yang, J.-S.; Zang, Y.-S.; Stebbing, J.; Xie, L.-P. A meta-analysis comparing responses of Asian versus non-Asian cancer patients to PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitor-based therapy. Oncoimmunology 2020, 9, 1781333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsouk, A.A.; Yang, A.; Sussman, J.H.; Elghawy, O.; Xu, J.; Xu, J.; Meng, L.; Koga, S.; Du, W.; Mamtani, R.; et al. Survival Disparities by Sex, Race, and Age in the Era of Contemporary Advanced Urothelial Carcinoma Therapy: A Real-World Analysis. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2025, 23, 102395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, T.; Nakagawa, K.; Park, K.; Ohe, Y.; Girard, N.; Kim, H.R.; Wu, Y.-L.; Gainor, J.; Lee, S.-H.; Chiu, C.-H.; et al. Nivolumab plus chemotherapy in epidermal growth factor receptor–mutated metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer after disease progression on epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors: Final results of checkmate 722. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 1252–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Huang, D.; Fan, Y.; Yu, X.; Liu, Y.; Shu, Y.; Ma, Z.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, J.; et al. Tislelizumab Versus Docetaxel in Patients with Previously Treated Advanced NSCLC (RATIONALE-303): A Phase 3, Open-Label, Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2023, 18, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.M.; Schulz, C.; Prabhash, K.; Kowalski, D.; Szczesna, A.; Han, B.; Rittmeyer, A.; Talbot, T.; Vicente, D.; Califano, R.; et al. First-line atezolizumab monotherapy versus single-agent chemotherapy in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer ineligible for treatment with a platinum-containing regimen (IPSOS): A phase 3, global, multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled study. Lancet 2023, 402, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neal, J.; Pavlakis, N.; Kim, S.W.; Goto, Y.; Lim, S.M.; Mountzios, G.; Fountzilas, E.; Mochalova, A.; Christoph, D.C.; Bearz, A.; et al. CONTACT-01: A Randomized Phase III Trial of Atezolizumab + Cabozantinib Versus Docetaxel for Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer After a Checkpoint Inhibitor and Chemotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 2393–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leighl, N.B.; Paz-Ares, L.; Abreu, D.R.; Hui, R.; Baka, S.; Bigot, F.; Nishio, M.; Smolin, A.; Ahmed, S.; Schoenfeld, A.J.; et al. LEAP-008: Lenvatinib Plus Pembrolizumab for Metastatic NSCLC That Has Progressed After an Anti-Programmed Cell Death Protein 1 or Anti-Programmed Cell Death Ligand 1 Plus Platinum Chemotherapy. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2025, 20, 1489–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbst, R.S.; Cho, B.C.; Zhou, C.; Burotto, M.; Dols, M.C.; Sendur, M.A.; Moiseyenko, V.; Casarini, I.; Nishio, M.; Hui, R.; et al. Lenvatinib Plus Pembrolizumab, Pemetrexed, and a Platinum as First-Line Therapy for Metastatic Nonsquamous NSCLC: Phase 3 LEAP-006 Study. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2025, 20, 1302–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reck, M.; Barlesi, F.; Yang, J.C.; Westeel, V.; Felip, E.; Özgüroğlu, M.; Dols, M.C.; Sullivan, R.; Kowalski, D.M.; Andric, Z.; et al. Avelumab Versus Platinum-Based Doublet Chemotherapy as First-Line Treatment for Patients With High-Expression Programmed Death-Ligand 1-Positive Metastatic NSCLC: Primary Analysis From the Phase 3 JAVELIN Lung 100 Trial. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2024, 19, 297–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.R.; Sugawara, S.; Lee, J.S.; Kang, J.; Inui, N.; Hida, T.; Lee, K.H.; Yoshida, T.; Tanaka, H.; Yang, C.; et al. First-line nivolumab, paclitaxel, carboplatin, and bevacizumab for advanced non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer: Updated survival analysis of the ONO-4538-52/TASUKI-52 randomized controlled trial. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 17061–17067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.C.; Lee, D.H.; Lee, J.S.; Fan, Y.; de Marinis, F.; Iwama, E.; Inoue, T.; Rodríguez-Cid, J.; Zhang, L.; Yang, C.-T.; et al. Phase III KEYNOTE-789 Study of Pemetrexed and Platinum With or Without Pembrolizumab for Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor-Resistant, EGFR-Mutant, Metastatic Nonsquamous Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 4029–4039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlesi, F.; Vansteenkiste, J.; Spigel, D.; Ishii, H.; Garassino, M.; de Marinis, F.; Özgüroğlu, M.; Szczesna, A.; Polychronis, A.; Uslu, R.; et al. Avelumab versus docetaxel in patients with platinum-treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (JAVELIN Lung 200): An open-label, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 1468–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhang, L.; Hu, J.; Wang, D.; Hu, C.; Zhou, J.; Wu, L.; Cao, L.; Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; et al. Pembrolizumab Plus Chemotherapy for Chinese Patients with Metastatic Squamous NSCLC in KEYNOTE-407. JTO Clin. Res. Rep. 2021, 2, 100225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.L.; Zhang, L.; Fan, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, Q.; Li, W.; Hu, C.; Chen, G.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, C.; et al. Randomized clinical trial of pembrolizumab vs. chemotherapy for previously untreated Chinese patients with PD-L1-positive locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: KEYNOTE-042 China Study. Int. J. Cancer 2021, 148, 2313–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.L.; Lu, S.; Cheng, Y.; Zhou, C.; Wang, J.; Mok, T.; Zhang, L.; Tu, H.-Y.; Wu, L.; Feng, J.; et al. Nivolumab Versus Docetaxel in a Predominantly Chinese Patient Population with Previously Treated Advanced NSCLC: CheckMate 078 Randomized Phase III Clinical Trial. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2019, 14, 867–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Fang, J.; Wang, Z.; Fan, Y.; Liu, Y.; He, J.; Zhou, J.; Hu, J.; Xia, J.; Liu, W.; et al. Results from the IMpower132 China cohort: Atezolizumab plus platinum-based chemotherapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 2666–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paz-Ares, L.; Ciuleanu, T.E.; Cobo, M.; Schenker, M.; Zurawski, B.; Menezes, J.; Richardet, E.; Bennouna, J.; Felip, E.; Juan-Vidal, O.; et al. First-line nivolumab plus ipilimumab combined with two cycles of chemotherapy in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 9LA): An international, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Fang, J.; Yu, Q.; Han, B.; Cang, S.; Chen, G.; Mei, X.; Yang, Z.; Ma, R.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Sintilimab Plus Pemetrexed and Platinum as First-Line Treatment for Locally Advanced or Metastatic Nonsquamous NSCLC: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Phase 3 Study (Oncology pRogram by InnovENT anti-PD-1-11). J. Thorac. Oncol. 2020, 15, 1636–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Wu, L.; Yu, X.; Xing, P.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wang, A.; Shi, J.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Z.; et al. Sintilimab versus docetaxel as second-line treatment in advanced or metastatic squamous non-small-cell lung cancer: An open-label, randomized controlled phase 3 trial (ORIENT-3). Cancer Commun. 2022, 42, 1314–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, M.; Şendur, M.A.N.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Park, K.; Lee, D.H.; Çiçin, I.; Yumuk, P.F.; Orlandi, F.J.; Leal, T.A.; Molinier, O.; et al. Pembrolizumab Plus Ipilimumab or Placebo for Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer With PD-L1 Tumor Proportion Score ≥ 50%: Randomized, Double-Blind Phase III KEYNOTE-598 Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 2327–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Feng, J.; Ma, S.; Chen, H.; Ma, Z.; Huang, C.; Zhang, L.; He, J.; Wang, C.; Zhou, J.; et al. KEYNOTE-033: Randomized phase 3 study of pembrolizumab vs. docetaxel in previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced NSCLC. Int. J. Cancer 2023, 153, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reck, M.; Mok, T.S.K.; Nishio, M.; Jotte, R.M.; Cappuzzo, F.; Orlandi, F.; Stroyakovskiy, D.; Nogami, N.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Moro-Sibilot, D.; et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab and chemotherapy in non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower150): Key subgroup analyses of patients with EGFR mutations or baseline liver metastases in a randomised, open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2019, 7, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, H.; McCleod, M.; Hussein, M.; Morabito, A.; Rittmeyer, A.; Conter, H.J.; Kopp, H.-G.; Daniel, D.; McCune, S.; Mekhail, T.; et al. Atezolizumab in combination with carboplatin plus nab-paclitaxel chemotherapy compared with chemotherapy alone as first-line treatment for metastatic non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower130): A multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 924–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuruda, K.M.; Hektoen, H.H.; Aamelfot, C.; Andreassen, B.K. Let’s talk about sex: Survival among females and males in a real-world cohort treated with pembrolizumab for non-small cell lung cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2025, 157, 1064–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, J.; Hong, J.; Tang, X.; Qiu, X.; Zhu, K.; Zhou, L.; Guo, D. Sex difference in response to non-small cell lung cancer immunotherapy: An updated meta-analysis. Ann. Med. 2022, 54, 2606–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; You, Z.; Liu, Y.; Fang, J.; Zhao, Q.; Sun, Z.; Song, Y.; Liu, J.; Sun, C. Sex-based immune microenvironmental feature heterogeneity in response to PD-1 blockade in combination with chemotherapy for patients with untreated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Med. 2024, 13, e7423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, C.; Cheema, A.S.; Asleh, K.; Finn, N.; Abdelsalam, M.; Ouellette, R.J. Sex-specific cytokine signatures as predictors of anti–PD-1 therapy response in non-small cell lung cancer. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1583421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, M.G.; Jensen, K.J.; Jimenez-Solem, E.; Qvortrup, C.; Andersen, J.A.L.; Petersen, T.S. Sex disparities in advanced non-small cell lung cancer survival: A Danish nationwide study. Lung Cancer 2025, 202, 108485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.; Flores, R.M.; Taioli, E. Unequal racial distribution of immunotherapy for late-stage non-small cell lung cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2023, 115, 1224–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nykaza, I.; An, A.; Villena-Vargas, J.; Mount, L.; Altorki, N.K.; Tamimi, R.M. Disparities in adherence to guideline-concordant care and receipt of immunotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer in the United States. Lung Cancer 2025, 206, 108661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Liu, J.; Miao, E.; Wang, S.; Zhang, F.; Wei, J.; Chung, J.; Xue, X.; Halmos, B.; Hosgood, H.D.; et al. Similar efficacy observed for first-line immunotherapy in racial/ethnic minority patients with metastatic NSCLC. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2023, 21, 1269–1280.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Zhang, D.; Braithwaite, D.; Karanth, S.D.; Tailor, T.D.; Clarke, J.M.; Akinyemiju, T. Racial differences in survival among advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer patients who received immunotherapy: An analysis of the US National Cancer Database. J. Immunother. 2022, 45, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peravali, M.; Ahn, J.; Chen, K.; Rao, S.; Veytsman, I.; Liu, S.V.; Kim, C. Safety and efficacy of first-line pembrolizumab in Black patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Oncologist 2021, 26, 694–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.; Untalan, M.; Flores, R.; Taioli, E. Immunotherapy in stage IV non-small cell lung cancer according to racial characteristics and community of residence. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, e20621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Wang, Y.; Tang, L.; Mansfield, A.S.; Adjei, A.A.; Leventakos, K.; Duma, N.; Wei, J.; Wang, L.; Liu, B.; et al. Efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 955440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, M.; Karanth, S.; Divaker, J.; Yoon, H.-S.; Yang, J.J.; Ratcliffe, M.; Blair, M.; Mehta, H.J.; Rackauskas, M.; Braithwaite, D. Participation in non-small cell lung cancer clinical trials in the United States by race/ethnicity. Clin. Lung Cancer 2025, 26, 52–57.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, M.L.; Fitzgerald, B.G.; Paz-Ares, L.; Cappuzzo, F.; A Jänne, P.; Peters, S.; Hirsch, F.R. New promises and challenges in the treatment of advanced non–small-cell lung cancer. Lancet 2024, 404, 803–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voruganti, T.; Soulos, P.R.; Mamtani, R.; Presley, C.J.; Gross, C.P. Association between age and survival trends in advanced non–small cell lung cancer after adoption of immunotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 9, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrichello, A.; Alessi, J.; Ricciuti, B.; Pecci, F.; Vaz, V.R.; Lamberti, G.; Turner, M.M.; Pfaff, K.L.; Rodig, S.J.; Awad, M.M. Immunophenotypic correlates and response to first-line pembrolizumab among elderly patients with PD-L1–high (≥50%) non–small cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 9054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Liu, Y.; He, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Yang, W.; Lu, J. Relationship between patients’ baseline characteristics and survival benefits in immunotherapy-treated non-small-cell lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Oncol. 2022, 2022, 3601942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, A.V.; Delmerico, J.; Sheng, H.; Huang, X.-W.; Liang, E.; Yan, L.; Gandhi, S.; Puzanov, I.; Jain, P.; Sakoda, L.C.; et al. Under-representation and under-reporting of minoritized racial and ethnic groups in clinical trials on immune checkpoint inhibitors. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2025, 21, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Source | Trial Name | n | % Male | OS Benefit | % White | % Asian | OS Benefit | % <65 | OS Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mok et al., 2024 [20] | Checkmate 722 | 294 | 39.8 | Neither | 6.1 | 93.9 | Neither | 56.8 | Neither |

| Zhou et al., 2023 [21] | RATIONALE 303 | 805 | 77.3 | Male | 17.6 | 82.4 | Both | 67.6 | Both |

| Lee et al., 2023 [22] | NCT03191786 | 453 | 72.4 | Male | 73 | 27.7 | Neither | NR | NR |

| Neal et al., 2024 [23] | CONTACT-01 | 355 | 73.5 | Male | 71.9 | 28.1 | Neither | 48.6 | Neither |

| Leighl et al., 2025 [24] | LEAP-008 | 374 | 66 | Neither | 80.7 | NR | Neither | 48.1 | Neither |

| Herbst et al., 2025 [25] | LEAP-006 | 748 | 67 | Neither | 67.2 | NR | Neither | 54.4 | Neither |

| Reck et al., 2024 [26] | JAVELIN Lung 100 Q2W38 | 367 | 73.6 | Neither | 71.8 | 28.2 | Neither | 54 | Neither |

| JAVELIN Lung 100 QW | 259 | 74.5 | Neither | 76.7 | 23.3 | White | 54.4 | <65 | |

| Kim et al., 2023 [27] | TASUKI-52 | 550 | 74.7 | Neither | NR | NR | NR | 44 | <65 |

| Yang et al., 2024 [28] | KEYNOTE-789 | 492 | 38.4 | Neither | NR | NR | NR | 55.3 | Neither |

| Barlesi et al., 2018 [29] | JAVELIN Lung 200 | 529 | 69.4 | Neither | 67.2 | 28.8 | NR | 52.7 | Neither |

| Cheng et al., 2021 [30] | KEYNOTE-407 | 125 | 95.2 | Neither | NR | NR | NR | 59.2 | Both |

| Wu et al., 2021 [31] | KEYNOTE-042 | 262 | 85.5 | Male | 0 | 100 | NR | 65.6 | <65 |

| Wu et al., 2019 [32] | CheckMate 078 | 504 | 78.8 | Male | NR | NR | NR | 74.8 | ≥65 |

| Lu et al., 2023 [33] | IMpower132 | 163 | 73 | Neither | 0 | 100 | NR | 68.7 | Neither |

| Paz-Ares et al., 2021 [34] | CheckMate 9LA | 719 | 70.1 | Male | NR | NR | NR | 49.2 | <65 |

| Yang et al., 2020 [35] | NCT03607539 | 398 | 76.1 | Male | 0 | 100 | NR | NR | NR |

| Shi et al., 2022 [36] | ORIENT-3 | 280 | 92.1 | Male | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Boyer et al., 2021 [37] | KEYNOTE-598 | 567 | 69.3 | Neither | NR | NR | NR | 49.5 | Neither |

| Ren et al., 2023 [38] | KEYNOTE-033 | 425 | 75.5 | Male | NR | NR | NR | 66.1 | ≥65 |

| Reck et al., 2019 [39] | IMpower150 ABCP vs. BCP | 800 | 59.9 | Male | 84.1 | 13.1 | NR | 55.5 | NR |

| IMpower150 ACP vs. BCP | 802 | 59.9 | Neither | 84.7 | 12 | NR | 56.3 | NR | |

| West et al., [40] 2019 | IMpower130 | 679 | 58.9 | Both | 90.1 | 2.2 | NR | 50.2 | Neither |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yaskolko, M.; Liu, C.; Barsouk, A.; Sussman, J.H.; Barsouk, A.A. Disparities in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) by Age, Sex, and Race: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor (ICI) Trials. Cancers 2026, 18, 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010128

Yaskolko M, Liu C, Barsouk A, Sussman JH, Barsouk AA. Disparities in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) by Age, Sex, and Race: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor (ICI) Trials. Cancers. 2026; 18(1):128. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010128

Chicago/Turabian StyleYaskolko, Maxim, Christopher Liu, Alexander Barsouk, Jonathan H. Sussman, and Adam A. Barsouk. 2026. "Disparities in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) by Age, Sex, and Race: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor (ICI) Trials" Cancers 18, no. 1: 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010128

APA StyleYaskolko, M., Liu, C., Barsouk, A., Sussman, J. H., & Barsouk, A. A. (2026). Disparities in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) by Age, Sex, and Race: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor (ICI) Trials. Cancers, 18(1), 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010128