Post-Operative Complications Do Not Influence Time to Adjuvant Treatment in Breast Cancer Patients Undergoing Implant-Based Reconstructions: Pre-Pectoral Versus Sub-Pectoral

Simple Summary

Abstract

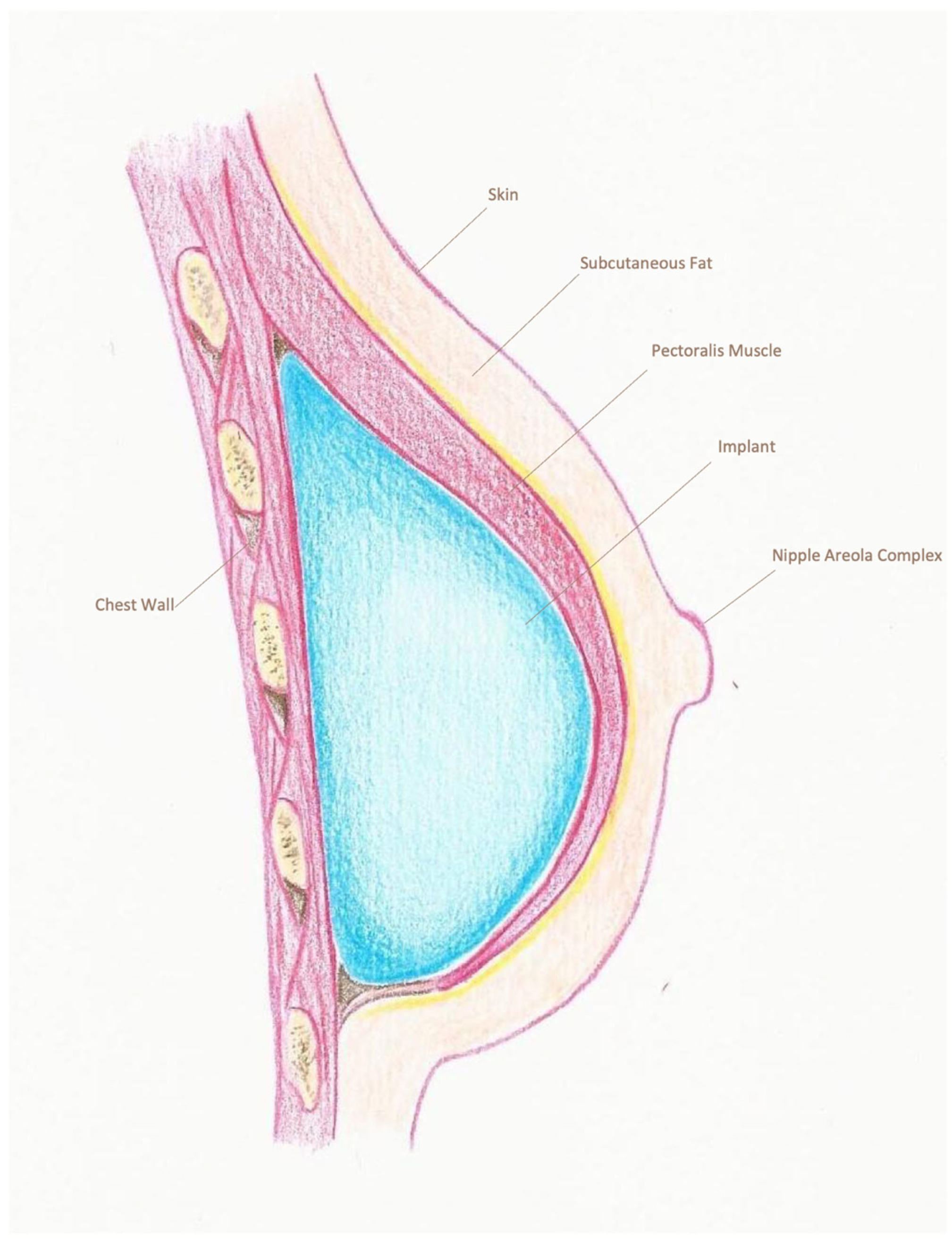

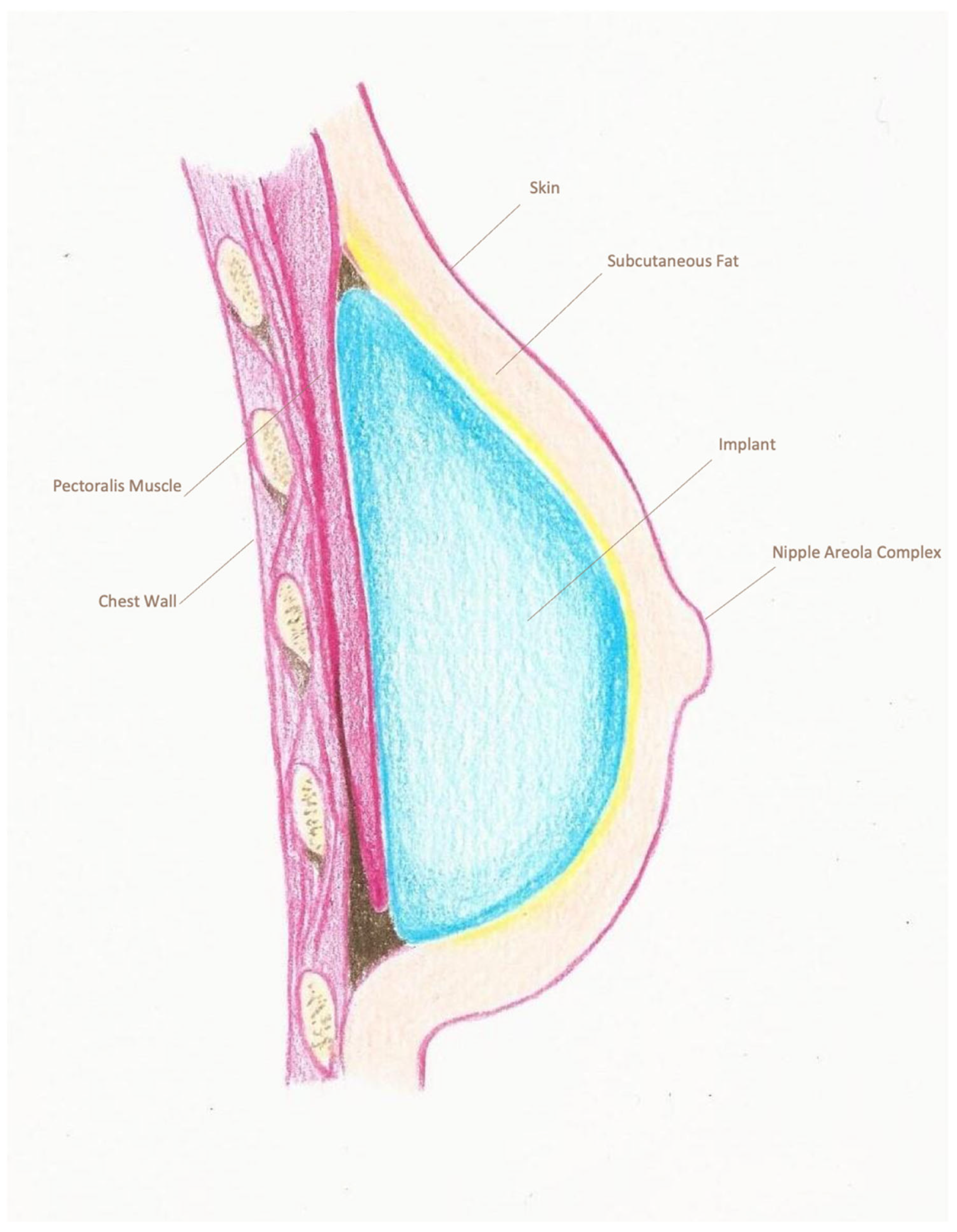

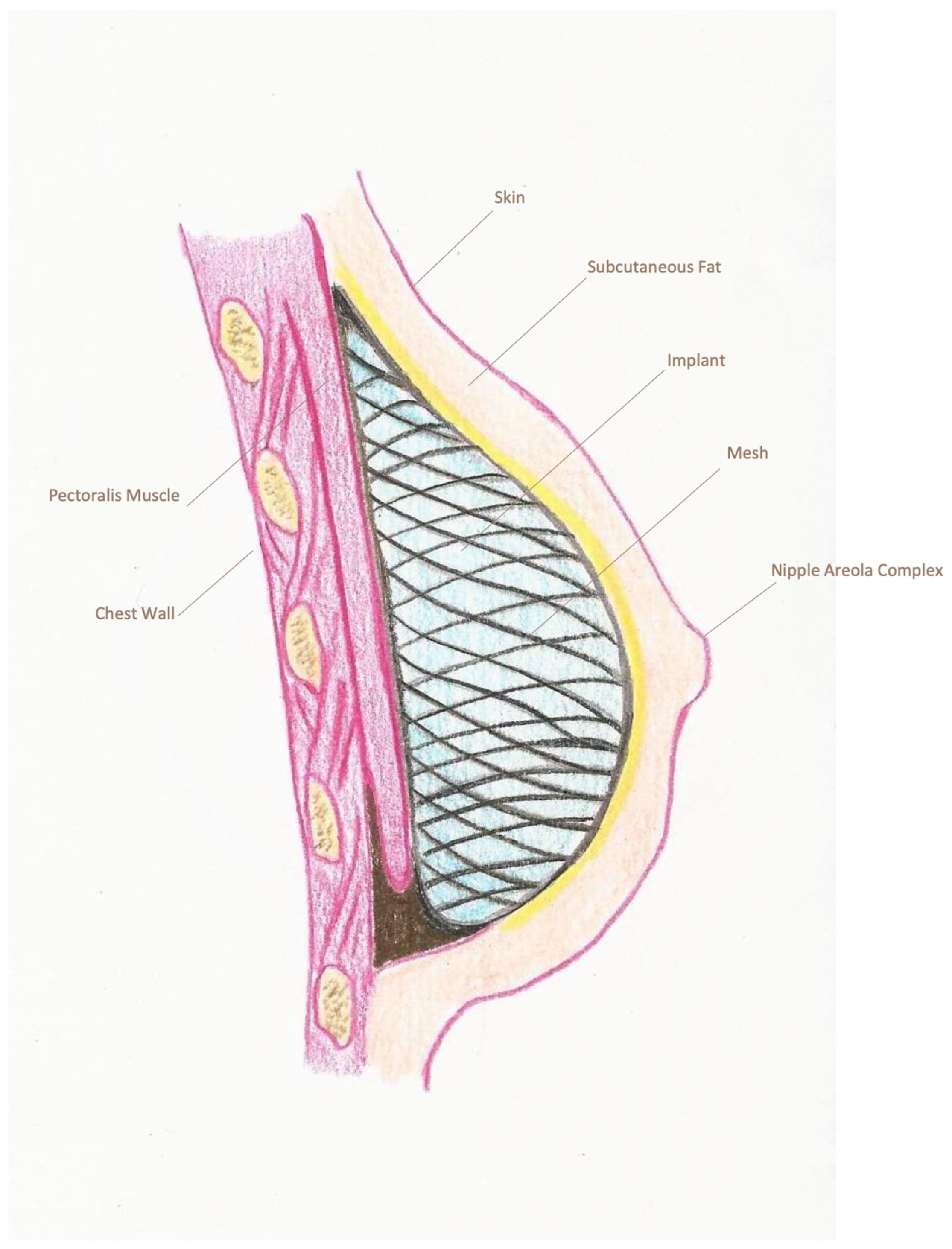

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jeevan, R.; Cromwell, D.A.; Browne, J.P.; Caddy, C.M.; Pereira, J.; Sheppard, C.; Greenaway, K.; van der Meulen, J.H. Findings of a national comparative audit of mastectomy and breast reconstruction surgery in England. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2014, 67, 1333–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribuffo, D.; Berna, G.; De Vita, R.; Di Benedetto, G.; Cigna, E.; Greco, M.; Valdatta, L.; Onesti, M.G.; Lo Torto, F.; Marcasciano, M.; et al. Dual-plane retro-pectoral versus pre-pectoral DTI breast reconstruction: An Italian multicenter experience. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2021, 45, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potter, S.; Conroy, E.J.; Cutress, R.I.; Williamson, P.R.; Whisker, L.; Thrush, S.; Skillman, J.; Barnes, N.L.P.; Mylvaganam, S.; Teasdale, E.; et al. Short-term safety outcomes of mastectomy and immediate implant-based breast reconstruction with and without mesh (iBRA): A multicentre, prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Della Rovere, G.Q.; Nava, M.; Bonomi, R.; Catanuto, G.; Benson, J.R. Skin-reducing mastectomy with breast reconstruction and sub-pectoral implants. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2008, 61, 1303–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A.; Nahabedian, M.Y.; Gabriel, A.; Macarios, D.; Parekh, M.; Wang, F.; Griffin, L.; Sigalove, S. Early assessment of post-surgical outcomes with pre-pectoral breast reconstruction: A literature review and meta-analysis. J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 117, 1119–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruccia, M.; Giudice, G.; Nacchiero, E.; Cazzato, G.; De Luca, G.M.; Gurrado, A.; Testini, M.; Elia, R. Pre-pectoral tissue expander and acellular dermal matrix for a two-stage muscle sparing breast reconstruction: Indications, surgical and clinical outcomes with histological and ultrasound follow-up—A population-based cohort study. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2025, 49, 1938–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernini, M.; Gigliucci, G.; Cassetti, D.; Tommasi, C.; Gaggelli, I.; Arlia, L.; Becherini, C.; Salvestrini, V.; Visani, L.; Nori Cucchiari, J.; et al. Pre-pectoral breast reconstruction with tissue expander entirely covered by acellular dermal matrix: Feasibility, safety and histological features resulting from the first 64 procedures. Gland Surg. 2024, 13, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houvenaeghel, G.; Bannier, M.; Bouteille, C.; Tallet, C.; Sabiani, L.; Charavil, A.; Bertrand, A.; Van Troy, A.; Buttarelli, M.; Teyssandier, C.; et al. Postoperative Outcomes of Pre-Pectoral Versus Sub-Pectoral Implant Immediate Breast Reconstruction. Cancers 2024, 16, 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubenstein, R.N.; Kim, M.; Plotsker, E.L.; Chu, J.J.; Bell, T.; McGriff, D.; Allen, R., Jr.; Dayan, J.H.; Stern, C.S.; Coriddi, M.; et al. Early complications in prepectoral tissue expander-based breast reconstruction. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 31, 2766–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamann, M.; Bensmann, E.; Andrulat, A.; Festl, J.; Saadat, G.; Klein, E.; Chronas, D.; Braun, M. Real-world data of perioperative complications in prepectoral implant-based breast reconstruction: A prospective cohort study. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2024, 310, 3077–3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanni, G.; Pellicciaro, M.; Buonomo, O.C. Axillary lymph node dissection in breast cancer patients: Obsolete or still necessary? Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2024, 47, 101107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rancati, A.; Angrigiani, C.; Hammond, D.; Nava, M.; Gonzalez, E.; Rostagno, R.; Gercovich, G. Preoperative digital mammography imaging in conservative mastectomy and immediate reconstruction. Gland Surg. 2016, 5, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panhofer, P.; Ferenc, V.; Schütz, M.; Gleiss, A.; Dubsky, P.; Jakesz, R.; Gnant, M.; Fitzal, F. Standardization of morbidity assessment in breast cancer surgery using the Clavien Dindo Classification. Int. J. Surg. 2014, 12, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinta, S.; Koh, D.J.; Sobti, N.; Packowski, K.; Rosado, N.; Austen, W.; Jimenez, R.B.; Specht, M.; Liao, E.C. Cost analysis of pre-pectoral implant-based breast reconstruction. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, T.C.; Hsieh, F.; Salinas, J.; Boyages, J. Immediate and long-term complications of direct-to-implant breast reconstruction after nipple- or skin-sparing mastectomy. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2018, 6, e1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirhaidari, S.J.; Azouz, V.; Wagner, D.S. Prepectoral versus subpectoral direct to implant immediate breast reconstruction. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2020, 84, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karoobi, M.; Yazd, S.M.M.; Nafissi, N.; Zolnouri, M.; Khosravi, M.; Sayad, S. Comparative clinical outcomes of using three-dimensional and TIGR mesh in immediate breast reconstruction surgery for breast cancer patients. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2023, 86, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.S.; You, H.J.; Lee, T.Y.; Kim, D.W. Comparing complications of biologic and synthetic mesh in breast reconstruction: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Arch. Plast. Surg. 2023, 50, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, M.; Glat, P. Potential of the SPY intraoperative perfusion assessment system to reduce ischemic complications in immediate postmastectomy breast reconstruction. Ann. Surg. Innov. Res. 2013, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliara, D.; Serra, P.L.; Pili, N.; Giardino, F.R.; Grieco, F.; Schiavone, L.; Lattanzi, M.; Rubino, C.; Ribuffo, D.; De Santis, G.; et al. Prediction of mastectomy skin flap necrosis with indocyanine green angiography and thermography: A retrospective comparative study. Clin. Breast Cancer 2024, 24, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrad, M.A.; Al Qurashi, A.A.; Shah Mardan, Q.N.M.; Alqarni, M.D.; Alhenaki, G.A.; Alghamdi, M.S.; Fathi, A.B.; Alobaidi, H.A.; Alnamlah, A.A.; Aljehani, S.K.; et al. Predictors of complications after breast reconstruction surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2022, 10, e4693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanni, G.; Pellicciaro, M.; Materazzo, M.; Bertolo, A.; Sadri, A.; Fazi, A.; Longo, B.; Berretta, M.; Cervelli, V.; Buonomo, O.C. Impact of incision type in breast cancer-conserving mastectomy: A comparative analysis of outcome. Updates Surg. 2025, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kupstas, A.R.; Hoskin, T.L.; Day, C.N.; Habermann, E.B.; Boughey, J.C. Effect of surgery type on time to adjuvant chemotherapy and impact of delay on breast cancer survival: A national cancer database analysis. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 26, 3240–3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Yu, L.; Huang, M.; Huang, Y.; Li, C.; Liang, Y.; Liang, W.; Qin, T. Comparative complications of prepectoral versus subpectoral breast reconstruction in patients with breast cancer: A meta-analysis. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1439293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dave, R.; O’Connell, R.; Rattay, T.; Tolkien, Z.; Barnes, N.; Skillman, J.; Williamson, P.; Conroy, E.; Gardiner, M.; Harnett, A.; et al. The iBRA-2 (immediate breast reconstruction and adjuvant therapy audit) study: Protocol for a prospective national multicentre cohort study to evaluate the impact of immediate breast reconstruction on the delivery of adjuvant therapy. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e012678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigalove, S.; Maxwell, G.P.; Sigalove, N.M.; Storm-Dickerson, T.L.; Pope, N.; Rice, J.; Gabriel, A. Prepectoral implant-based breast reconstruction: Rationale, indications, and preliminary results. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2017, 139, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, G.; Yu, N.; Huang, J.; Long, X. Prepectoral versus subpectoral implant-based breast reconstruction: A meta-analysis. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2020, 85, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanni, G.; Pellicciaro, M.; Materazzo, M.; Dauri, M.; D’angelillo, R.M.; Buonomo, C.; De Majo, A.; Pistolese, C.; Portarena, I.; Mauriello, A.; et al. Awake breast cancer surgery: Strategy in the beginning of COVID-19 emergency. Breast Cancer 2021, 28, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonomo, O.C.; Vinci, D.; De Carolis, G.; Pellicciaro, M.; Petracca, F.; Sadri, A.; Buonomo, C.; Dauri, M.; Vanni, G. Role of breast-conserving surgery on the national health system economy from and to SARS-COVID-19 era. Front. Surg. 2022, 8, 705174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onuma, A.E.; Zhang, H.; Gil, L.; Huang, H.; Tsung, A. Surgical stress promotes tumor progression: A focus on the impact of the immune response. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 4096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, X.; Kuang, X.; Li, J. The impact of perioperative events on cancer recurrence and metastasis in patients after radical gastrectomy: A review. Cancers 2022, 14, 3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbitany, H.; Piper, M.; Lentz, R. Prepectoral Breast Reconstruction: A Safe Alternative to Submuscular Prosthetic Reconstruction following Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2017, 140, 432–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahabedian, M.Y. Implant-based breast reconstruction following conservative mastectomy: One-stage vs. two-stage approach. Gland Surg. 2016, 5, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grigor, E.J.M.; Stein, M.J.; Arnaout, A.; Ghaedi, B.; Cormier, N.; Ramsay, T.; Zhang, J. The effect of immediate breast reconstruction on adjuvant therapy delay, locoregional recurrence, and disease-free survival. Breast J. 2021, 27, 857–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colwell, A.S.; Tessler, O.; Lin, A.M.; Liao, E.; Winograd, J.; Cetrulo, C.L.; Tang, R.; Smith, B.L.; Austen, W.G., Jr. Breast reconstruction following nipple-sparing mastectomy: Predictors of complications, reconstruction outcomes, and 5-year trends. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2014, 133, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falick Michaeli, T.; Hatoom, F.; Skripai, A.; Wajnryt, E.; Allweis, T.M.; Paluch-Shimon, S.; Shachar, Y.; Popovtzer, A.; Wygoda, M.; Blumenfeld, P. Complication rates after mastectomy and reconstruction in breast cancer patients treated with hypofractionated radiation therapy compared to conventional fractionation: A single institutional analysis. Cancers 2025, 17, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scardina, L.; Petrazzuolo, E.; Accetta, C.; Carnassale, B.; D’Archi, S.; Di Leone, A.; Di Pumpo, A.; Di Guglielmo, E.; De Lauretis, F.; Franco, A.; et al. Surgical management of ipsilateral breast cancer recurrence after conservative mastectomy and prepectoral breast reconstruction: Exploring the role of wide local excision. Cancers 2025, 17, 2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Chen, C.; Chen, C.; Song, H.; Li, M.; Yan, J.; Lv, X. Serum Raman spectroscopy combined with convolutional neural network for rapid diagnosis of HER2-positive and triple-negative breast cancer. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023, 286, 122000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuniolo, L.; Diaz, R.; Anastasia, D.; Murelli, F.; Cornacchia, C.; Depaoli, F.; Gipponi, M.; Margarino, C.; Boccardo, C.; Franchelli, S.; et al. Indocyanine Green Angiography to Predict Complications in Subcutaneous Mastectomy: A Single-Center Experience. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pre-Pectoral Group (n = 235) | Sub-Pectoral Group (n = 366) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 59.8 [28–92] | 60.4 [34–83] | 0.631 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.2 [20.1–33.2] | 23.7 [20.9–34.1] | 0.882 |

| Smoker (Yes) | 33 (14.5%) | 34 (12.6%) | 0.112 |

| Diabetes Mellitus II (Yes) | 4 (1.7%) | 18 (4.9%) | 0.045 |

| Bilateral Mastectomy (Yes) | 45 (19.2%) | 78 (21.4%) | 0.533 |

| Neoadjuvant CHT (Yes) | 50 (21.3%) | 123 (33.6%) | 0.002 |

| Previous RT | 13 (5.5%) | 23 (6.3%) | 0.860 |

| >10 Years Before | 9 (3.8%) | 13 (3.5%) | 1.000 |

| <10 Years Before | 4 (1.7%) | 10 (2.8%) | 0.581 |

| Radiological MSF Thickness | 0.075 | ||

| Type I | 51 (21.7%) | 109 (29.8%) | |

| Type II | 149 (63.4%) | 205 (56.1%) | |

| Type III | 38 (16.2%) | 52 (14.2%) | |

| Type of Mastectomy | 0.029 | ||

| Simplex | 146 (62.1%) | 193 (52.7%) | |

| Skin Sparing | 21 (8.9%) | 64 (17.5%) | |

| NAC Sparing | 62 (26.4%) | 97 (26.5%) | |

| Skin Reducing | 6 (2.5%) | 12 (3.3%) | |

| Type of Implant | <0.001 | ||

| DTI | 112 (47.7%) | 114 (31.1%) | |

| Tissue Expander | 123 (52.3%) | 252 (68.9%) | |

| Mesh (Yes) | 42 (17.9%) | 25 (6.9%) | <0.001 |

| Mastectomy Indications | 0.445 | ||

| Invasive Carcinoma * | 187 (79.5%) | 304 (83.1%) | |

| Pure DCIS | 28 (11.9%) | 40 (10.9%) | |

| Other ** | 20 (7.5%) | 22 (6.1%) | |

| Specimen Breast Volume (cc) | 476.3 ± 193.4 | 501.1 ± 211.3 | 0.141 |

| Implant Breast Volume (cc) | 423.3 ± 81.7 | 451.5 ± 96.0 | 0.001 |

| Axillary Surgery | 0.944 | ||

| SNLB | 124 (52.8%) | 199 (54.4%) | |

| ALND | 76 (32.3%) | 123 (33.6%) | |

| NO | 25 (10.6%) | 44 (12.1%) | |

| Adjuvant RT | 10 (4.3%) | 19 (5.2%) | 0.698 |

| Hospitalization | 2 [0:5] | 2 [1:6] | 0.964 |

| Surgical Time | 135 [60:167] | 141 [89:240] | <0.001 |

| Pre-Pectoral Group (n = 235) | Sub-Pectoral Group (n = 366) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complications | 56 (23.8%) | 74 (20.2%) | 0.310 |

| Minor Complications (I–II) | 38 (16.2%) | 40 (10.9%) | 0.081 |

| Major Complications (IIIa–IIIb) | 18 (7.7%) | 34 (9.3%) | 0.55 |

| Delayed Wound Healing | 21 (9.0%) | 16 (4.3%) | 0.035 |

| Seroma | 5 (2.1%) | 9 (2.5%) | 0.793 |

| Hematoma | 11 (4.7%) | 13 (3.5%) | 0.490 |

| Bleeding | 1 (1.7%) | 11 (4.9%) | 0.057 |

| Implant Infection | 6 (2.6%) | 12 (3.3%) | 0.611 |

| Implant Loss | 12 (5.1%) | 13 (3.6%) | 0.352 |

| Re-Operation | 14 (6.0%) | 15 (4.1%) | 0.299 |

| Interval Time to Adjuvant Treatment > 60 days | 37 (15.7%) | 49 (13.4%) | 0.636 |

| OR | 95% CI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Implant Position Pre-Pectoral | 0.912 | 0.511–1.321 | 0.652 |

| Mesh (Yes) | 0.655 | 0.210–1.711 | 0.115 |

| Smoker (Yes) | 2.891 | 0.915–3.716 | 0.029 |

| Diabetes M II (Yes) | 3.056 | 1.201–8.612 | 0.049 |

| Skin-Reducing Mastectomy | 2.111 | 1.337–4.391 | 0.018 |

| Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy | 0.774 | 0.235–1.661 | 0.092 |

| Simple Mastectomy | 0.341 | 0.122–0.921 | 0.133 |

| Age (>60 years old) | 1.136 | 0.647–1.953 | 0.602 |

| ALND (Yes) | 1.219 | 0.407–3.524 | 0.391 |

| Implant Breast Volume (>400 cc) | 1.078 | 0.335–1.869 | 0.444 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Vanni, G.; Pellicciaro, M.; Materazzo, M.; Bertolo, A.; Sadri, A.; Campanella, E.; Eskiu, D.; Portarena, I.; Longo, B.; Cervelli, V.; et al. Post-Operative Complications Do Not Influence Time to Adjuvant Treatment in Breast Cancer Patients Undergoing Implant-Based Reconstructions: Pre-Pectoral Versus Sub-Pectoral. Cancers 2026, 18, 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010109

Vanni G, Pellicciaro M, Materazzo M, Bertolo A, Sadri A, Campanella E, Eskiu D, Portarena I, Longo B, Cervelli V, et al. Post-Operative Complications Do Not Influence Time to Adjuvant Treatment in Breast Cancer Patients Undergoing Implant-Based Reconstructions: Pre-Pectoral Versus Sub-Pectoral. Cancers. 2026; 18(1):109. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010109

Chicago/Turabian StyleVanni, Gianluca, Marco Pellicciaro, Marco Materazzo, Alice Bertolo, Amir Sadri, Elisa Campanella, Denisa Eskiu, Ilaria Portarena, Benedetto Longo, Valerio Cervelli, and et al. 2026. "Post-Operative Complications Do Not Influence Time to Adjuvant Treatment in Breast Cancer Patients Undergoing Implant-Based Reconstructions: Pre-Pectoral Versus Sub-Pectoral" Cancers 18, no. 1: 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010109

APA StyleVanni, G., Pellicciaro, M., Materazzo, M., Bertolo, A., Sadri, A., Campanella, E., Eskiu, D., Portarena, I., Longo, B., Cervelli, V., & Buonomo, O. C. (2026). Post-Operative Complications Do Not Influence Time to Adjuvant Treatment in Breast Cancer Patients Undergoing Implant-Based Reconstructions: Pre-Pectoral Versus Sub-Pectoral. Cancers, 18(1), 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010109