Serum Levels of Soluble Forms of Fas and FasL in Patients with Pancreatic and Papilla of Vater Adenocarcinomas

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Patients and Healthy Controls

2.2. Blood Samples and Assays

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

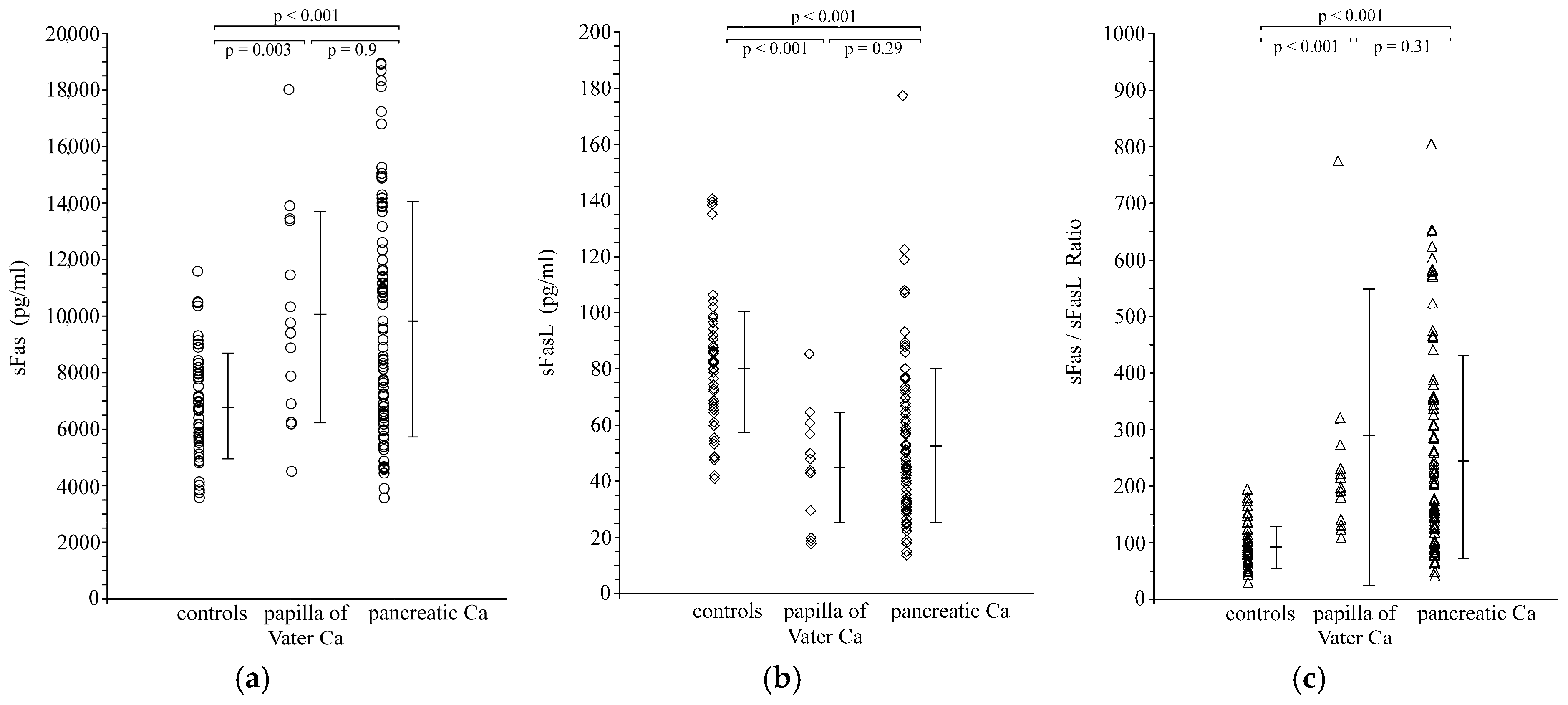

3.1. Serum Levels of sFas, sFasL and sFas/sFasLRatio in Carcinoma Patients and Healthy Controls

3.2. Correlations Between Serum Levels of sFas, sFasL and sFas/sFasL Ratio in Carcinoma Patients and Pathological Features

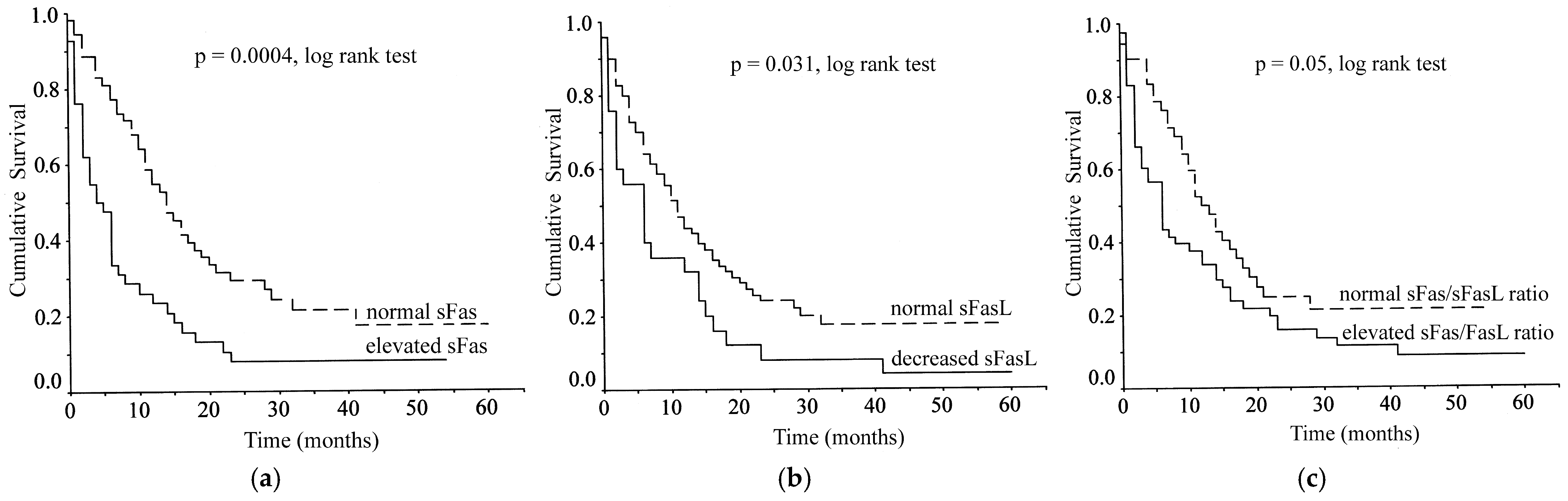

3.3. Correlations Between Serum Levels of sFas, sFasL and sFas/sFasLRatio and Patient Survival

3.4. The Effect of Surgery on Serum Levels of sFas, sFasL and sFas/sFasL Ratio

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oehm, A.; Behrmann, I.; Falk, W.; Pawlita, M.; Maier, G.; Klas, C.; Li-Weber, M.; Richards, S.; Dhein, J.; Trauth, B.C. Purification and molecular cloning of the APO-1 cell surface antigen, a member of the tumor necrosis factor/nerve growth factor receptor superfamily. Sequence identity with the Fas antigen. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 10709–10715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suda, T.; Takahashi, T.; Golstein, P.; Nagata, S. Molecular cloning and expression of the Fas ligand, a novel member of the tumor necrosis factor family. Cell 1993, 75, 1169–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itoh, N.; Yonehara, S.; Ishii, A.; Yonehara, M.; Mizushima, S.; Sameshima, M.; Hase, A.; Seto, Y.; Nagata, S. The polypeptide encoded by the cDNA for human cell surface antigen Fas can mediate apoptosis. Cell 1991, 66, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderson, M.R.; Tough, T.W.; Davis-Smith, T.; Braddy, S.; Falk, B.; Schooley, K.A.; Goodwin, R.G.; Smith, C.A.; Ramsdell, F.; Lynch, D.H. Fas ligand mediates activation-induced cell death in human T lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 1995, 181, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithäuser, F.; Dhein, J.; Mechtersheimer, G.; Koretz, K.; Bruderlein, S.; Henne, C.; Schmidt, A.; Debatin, K.M.; Krammer, P.H.; Moller, P. Constitutive and induced expression of APO-1, a new member of the nerve growth factor/tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, in normal and neoplastic cells. Lab. Investig. 1993, 69, 415–429. [Google Scholar]

- Xerri, L.; Devilard, E.; Hassoun, J.; Mawas, C.; Birg, F. Fas ligand is not only expressed in immune privileged human organs but is also coexpressed with Fas in various epithelial tissues. Mol. Pathol. 1997, 50, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uckan, D.; Steele, A.; Cherry; Wang, B.Y.; Chamizo, W.; Koutsonikolis, A.; Gilbert-Barness, E.; Good, R.A. Trophoblasts express Fasligand: A proposed mechanism for immune privilege in placenta and maternal invasion. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 1997, 3, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, P.M.; Pan, F.; Plambeck, S.; Ferguson, T.A. FasL-Fas interactions regulate neovascularization in the cornea. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003, 44, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascino, I.; Fiucci, G.; Papoff, G.; Ruberti, G. Three functional soluble forms of the human apoptosis-inducing Fas molecule are produced by alternative splicing. J. Immunol. 1995, 154, 2706–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M.; Suda, T.; Takahashi, T.; Nagata, S. Expression of the functional soluble form of human fas ligand in activated lymphocytes. EMBO J. 1995, 14, 1129–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayagaki, N.; Kawasaki, A.; Ebata, T.; Ohmoto, H.; Ikeda, S.; Inoue, S.; Yoshino, K.; Okumura, K.; Yagita, H. Metalloproteinase-mediated release of human Fas ligand. J. Exp. Med. 1995, 82, 1777–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, K.; Shimosegawa, T.; Masamune, A.; Hirota, M.; Koizumi, M.; Toyota, T. Fas ligand is frequently expressed in human pancreatic duct cell carcinoma. Pancreas 1999, 19, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornmann, M.; Ishiwata, T.; Kleeff, J.; Beger, H.G.; Korc, M. Fas and Fas-ligand expression in human pancreatic cancer. Ann. Surg. 2000, 231, 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernick, N.L.; Sarkar, F.H.; Tabaczka, P.; Kotcher, G.; Frank, J.; Adsay, N.V. Fas and Fas ligand expression in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Pancreas 2002, 25, e36–e41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, T.; Elnemr, A.; Kitagawa, H.; Kayahara, M.; Takamura, H.; Fujimura, T.; Nishimura, G.; Shimizu, K.; Yi, S.Q.; Miwa, K. Fas ligand expression in human pancreatic cancer. Oncol. Rep. 2004, 12, 749–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungefroren, H.; Voss, M.; Jansen, M.; Roeder, C.; Henne-Bruns, D.; Kremer, B.; Kalthoff, H. Human pancreatic adenocarcinomas express Fas and Fas ligand yet are resistant to Fas-mediated apoptosis. Cancer Res. 1998, 58, 1741–1749. [Google Scholar]

- von Bernstorff, W.; Spanjaard, R.A.; Chan, A.K.; Lockhart, D.C.; Sadanaga, N.; Wood, I.; Peiper, M.; Goedegebuure, P.S.; Eberlein, T.J. Pancreatic cancer cells can evade immune surveillance via nonfunctional Fas (APO-1/CD95) receptors and aberrant expression of functional Fas ligand. Surgery 1999, 125, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnemr, A.; Ohta, T.; Yachie, A.; Kayahara, M.; Kitagawa, H.; Fujimura, T.; Ninomiya, I.; Fushida, S.; Nishimura, G.I.; Shimizu, K.; et al. Human pancreatic cancer cells disable function of Fas receptors at several levels in Fas signal transduction pathway. Int. J. Oncol. 2001, 18, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen-Schaub, L.B.; van Golen, K.L.; Hill, L.L.; Price, J.E. Fas and Fas ligand interactions suppress melanoma lung metastasis. J. Exp. Med. 1998, 188, 1717–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elnemr, A.; Ohta, T.; Yachie, A.; Kayahara, M.; Kitagawa, H.; Ninomiya, I.; Fushida, S.; Fujimura, T.; Nishimura, G.; Shimizu, K.; et al. Human pancreatic cancer cells express non-functional Fas receptors and counterattack lymphocytes by expressing Fas ligand; a potential mechanism for immune escape. Int. J. Oncol. 2001, 18, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knipping, E.; Debatin, K.M.; Stricker, K.; Heilig, B.; Eder, A.; Krammer, P.H. Identification of soluble APO-1 in supernatants of human B- and T-cell lines and increased serum levels in B- and T-cell leukemias. Blood 1995, 85, 1562–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midis, G.P.; Shen, Y.; Owen-Schaub, L.B. Elevated soluble Fas (sFas) levels in nonhematopoietic human malignancy. Cancer Res. 1996, 56, 3870–3874. [Google Scholar]

- Ugurel, S.; Rappl, G.; Tilgen, W.; Reinhold, U. Increased soluble CD95 (sFas/CD95) serum level correlates with poor prognosis in melanoma patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 2001, 7, 1282–1286. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, J.; Zhou, T.; Liu, C.; Shapiro, J.P.; Brauer, M.J.; Kiefer, M.C.; Barr, P.J.; Mountz, J.D. Protection from Fas-mediated apoptosis by a soluble form of the Fas molecule. Science 1994, 263, 1759–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellone, G.; Smirne, C.; Carbone, A.; Mareschi, K.; Dughera, L.; Farina, E.C.; Alabiso, O.; Valente, G.; Emanuelli, G.; Rodeck, U. Production and pro-apoptotic activity of soluble CD95 ligand in pancreatic carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2000, 6, 2448–2455. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schneider, P.; Holler, N.; Bodmer, J.L.; Hahne, M.; Frei, K.; Fontana, A.; Tschopp, J. Conversion of membrane-bound Fas(CD95) ligand to its soluble form is associated with downregulation of its proapoptotic activity and loss of liver toxicity. J. Exp. Med. 1998, 187, 1205–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsutsumi, S.; Kuwano, H.; Shimura, T.; Morinaga, N.; Mochiki, E.; Asao, T. Circulating soluble Fas ligand in patients with gastric carcinoma. Cancer 2000, 89, 2560–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizutani, Y.; Hongo, F.; Sato, N.; Ogawa, O.; Yoshida, O.; Miki, T. Significance of serum soluble Fas ligand in patients with bladder carcinoma. Cancer 2001, 92, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suda, T.; Hashimoto, H.; Tanaka, M.; Ochi, T.; Nagata, S. Membrane Fas ligand kills human peripheral blood T lymphocytes, and soluble Fas ligand blocks the killing. J. Exp. Med. 1997, 186, 2045–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plate, J.M.; Shott, S.; Harris, J.E. Immunoregulation in pancreatic cancer patients. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 1999, 48, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichmann, E. The biological role of the Fas/FasL system during tumor formation and progression. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2002, 12, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, J.J.; Liang, W.B.; Zhu, R.; Wang, B.; Miao, Y.; Xu, Z.K. Pancreatic cancer counterattack: MUC4 mediates Fas-independent apoptosis of antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte. Oncol. Rep. 2014, 31, 1768–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medema, J.P.; de Jong, J.; van Hall, T.; Melief, C.J.; Offringa, R. Immune escape of tumors in vivo by expression of cellular FLICE-inhibitory protein. J. Exp. Med. 1999, 190, 1033–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Song, S.; He, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Li, D.; Zhu, D. Silencing of decoy receptor 3 (DcR3) expression by siRNA in pancreatic carcinoma cells induces Fas ligand-mediated apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2013, 32, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Suda, T.; Haze, K.; Nakamura, N.; Sato, K.; Kimura, F.; Motoyoshi, K.; Mizuki, M.; Tagawa, S.; Ohga, S.; et al. Fas ligand in human serum. Nat. Med. 1996, 2, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuya, Y.; Nagakawa, O.; Fuse, H. Prognostic significance of serum soluble Fas level and its change during regression and progression of advanced prostate cancer. Endocr. J. 2003, 50, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagao, M.; Nakajima, Y.; Hisanaga, M.; Kayagaki, N.; Kanehiro, H.; Aomatsu, Y.; Ko, S.; Yagita, H.; Yamada, T.; Okumura, K.; et al. The alteration of Fas receptor and ligand system in hepatocellular carcinomas: How do hepatoma cells escape from the host immune surveillance in vivo? Hepatology 1999, 30, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, M.; Sasaki, T.; Miyata, H.; Yamasaki, S.; Kuwahara, K.; Chayama, K. Fas and Fas ligand: Expression and soluble circulating levels in bile duct carcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 2004, 11, 1183–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konno, R.; Tadao, T.; Shinji, S.; Akira, Y. Serum soluble Fas level as a prognostic factor in patients with gynaecological malignancies. Clin. Cancer Res. 2000, 6, 3576–3580. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hefler, L.; Mayerhofer, K.; Nardi, A.; Reinthaller, A.; Kainz, C.; Tempfer, C. Serum soluble Fas levels in ovarian cancer. Obstet. Gynecol. 2000, 96, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo, P.; Solano, T.; Vazquez, B.; Bauza, A.; Idoate, M. Fas and Fas ligand: Expression and soluble circulating levels in cutaneous malignant melanoma. Br. J. Dermatol 2002, 147, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jodo, S.; Kobayashi, S.; Nakajima, Y.; Matsunaga, T.; Nakayama, N.; Ogura, N.; Kayagaki, N.; Okumura, K.; Koike, T. Elevated serum levels of soluble Fas/APO-1 (CD95) in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1998, 112, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nonomura, N.; Nishimura, K.; Ono, Y.; Fukui, T.; Harada, Y.; Takaha, N.; Takahara, S.; Okuyama, A. Soluble Fas in serum from patients with renal cell carcinoma. Urology 2000, 55, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Controls (n = 53) | Pancreatic Carcinoma (n = 82) | Papilla of Vater Carcinoma (n = 14) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 67 ± 11 | 70 ± 9 | 68 ± 10 |

| Sex (M/F) | 35/18 | 54/28 | 13/1 |

| sFas (pg/mL) | 6784 ± 1864 | 9852 ± 4158 * | 9980 ± 3716 * |

| sFasL(pg/mL) | 80.6 ± 23.2 | 52.8 ± 27.2 * | 45.1 ± 19.2 * |

| sFas/sFasL ratio | 91.2 ± 37.5 | 245.4 ± 175.3 * | 290.4 ± 258.2 * |

| sFas (pg/mL) | sFasL(pg/mL) | sFas/sFasLRatio | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor class | |||

| T1 (n = 4) | 10,312 ± 3453 | 60.6 ± 24.3 | 216.3 ± 170.9 |

| T2 (n = 14) | 10,261 ± 4462 | 59.2 ± 29.3 | 235.7 ± 194.2 |

| T3 (n = 53) | 9179 ± 3565 | 51.4 ± 27.5 | 237.9 ± 176.8 |

| T4 (n = 25) | 11,049 ± 4836 | 46.5 ± 21.8 | 296.5 ± 214.8 |

| Lymph node metastases | |||

| N0 (n = 30) | 8750 ± 3222 | 59.8 ± 32.3 | 198.2 ± 156.2 |

| N1 (n = 66) | 10,380 ± 4340 * | 47.9 ± 22.3 * | 276.4 ± 197.9 * |

| Distant metastases | |||

| M0 (n = 75) | 8632 ± 3317 | 54.3 ± 27.2 | 211.8 ± 175.3 |

| M1 (n = 21) | 14,296 ± 3458 ** | 42.2 ± 20.2 ** | 395.3 ± 166.3 ** |

| TNM stage | |||

| I (n = 10) | 8450 ± 2564 | 67.9 ± 24.7 | 139.9 ± 62.8 |

| II (n = 50) | 8507 ± 3217 | 53.6 ± 27.8 | 212.5 ± 169.6 |

| III (n = 15) | 9170 ± 4163 | 47.8 ± 25.3 | 257.5 ± 230.9 |

| IV (n = 21) | 14,296 ± 3458 *** | 42.2 ± 20.2 *** | 395.3 ± 166.3 *** |

| Tumor differentiation | |||

| Well (n = 10) | 8322 ± 2874 | 55.5 ± 28.6 | 196.3 ± 147.1 |

| Moderate (n = 22) | 9628 ± 3658 | 50.3 ± 33.1 | 266.5 ± 199.7 |

| Poor (n = 15) | 8796 ± 3624 | 53.5 ± 22.9 | 200.1 ± 114.1 |

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.01 | 0.98–1.03 | 0.45 |

| Sex (Male vs. Female) | 0.76 | 0.47–1.24 | 0.27 |

| Tumor type (Pancreas vs. Papilla of Vater) | 3.7 | 1.58–8.67 | 0.003 |

| Tumor resection (curative vs. unresectable) | 2.60 | 1.59–4.25 | 0.000 |

| Differentiation (Well vs. Moderate vs. Poor) | 1.49 | 0.88–2.53 | 0.137 |

| T Class (T1 vs. T2 vs. T3 vs. T4) | 1.89 | 1.34–2.67 | 0.000 |

| Nodal status (N0 vs. N1) | 1.98 | 1.19–3.29 | 0.008 |

| Distant metastases (M0 vs. M1) | 3.58 | 1.99–6.44 | 0.000 |

| TNM Stage (I vs. II vs. III vs. IV) | 2.05 | 1.57–2.68 | 0.000 |

| sFas (Elevated vs. Normal) | 2.12 | 1.33–3.36 | 0.001 |

| sFasL (Elevated vs. Normal) | 1.72 | 1.05–2.81 | 0.032 |

| sFas/FasL ratio (Elevated vs. Normal) | 1.51 | 0.95–2.40 | 0.078 |

| Controls | Before Surgery | After Surgery | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radical | n = 53 | n = 39 | n = 35 |

| sFas (pg/mL) | 6784 ± 1864 | 8584 ± 2975 * | 7231 ± 2755 ** |

| sFasL(pg/mL) | 80.6 ± 23.2 | 54.5 ± 30.4 * | 72.9 ± 37.3 ** |

| sFas/sFasL ratio | 91.2 ± 37.5 *** | 212.3 ± 158.9 * | 119.7 ± 72.3 ** |

| Palliative/unresectable | n = 53 | n = 57 | n = 53 |

| sFas (pg/mL) | 6784 ± 1864 *** | 10,752 ± 4502 * | 11,016 ± 4258 |

| sFasL(pg/mL) | 80.6 ± 23.2 *** | 49.7 ± 23.1 * | 51.2 ± 18 |

| sFas/sFasL ratio | 91.2 ± 37.5 *** | 279.1 ± 203.4 * | 256.2 ± 165.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Anagnostoulis, S.; Bolanaki, H.; Asimakopoulos, B.; Ouroumidis, D.; Koutini, M.; Patris, S.; Tzimagiorgis, I.; Karayiannakis, A.J. Serum Levels of Soluble Forms of Fas and FasL in Patients with Pancreatic and Papilla of Vater Adenocarcinomas. Cancers 2026, 18, 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010106

Anagnostoulis S, Bolanaki H, Asimakopoulos B, Ouroumidis D, Koutini M, Patris S, Tzimagiorgis I, Karayiannakis AJ. Serum Levels of Soluble Forms of Fas and FasL in Patients with Pancreatic and Papilla of Vater Adenocarcinomas. Cancers. 2026; 18(1):106. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010106

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnagnostoulis, Stavros, Helen Bolanaki, Byron Asimakopoulos, Dimitrios Ouroumidis, Maria Koutini, Spyridon Patris, Ioannis Tzimagiorgis, and Anastasios J. Karayiannakis. 2026. "Serum Levels of Soluble Forms of Fas and FasL in Patients with Pancreatic and Papilla of Vater Adenocarcinomas" Cancers 18, no. 1: 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010106

APA StyleAnagnostoulis, S., Bolanaki, H., Asimakopoulos, B., Ouroumidis, D., Koutini, M., Patris, S., Tzimagiorgis, I., & Karayiannakis, A. J. (2026). Serum Levels of Soluble Forms of Fas and FasL in Patients with Pancreatic and Papilla of Vater Adenocarcinomas. Cancers, 18(1), 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010106