Systematic Exploration of Molecular Mechanisms and Natural Herbal Therapeutic Strategies for Cancer Cachexia

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

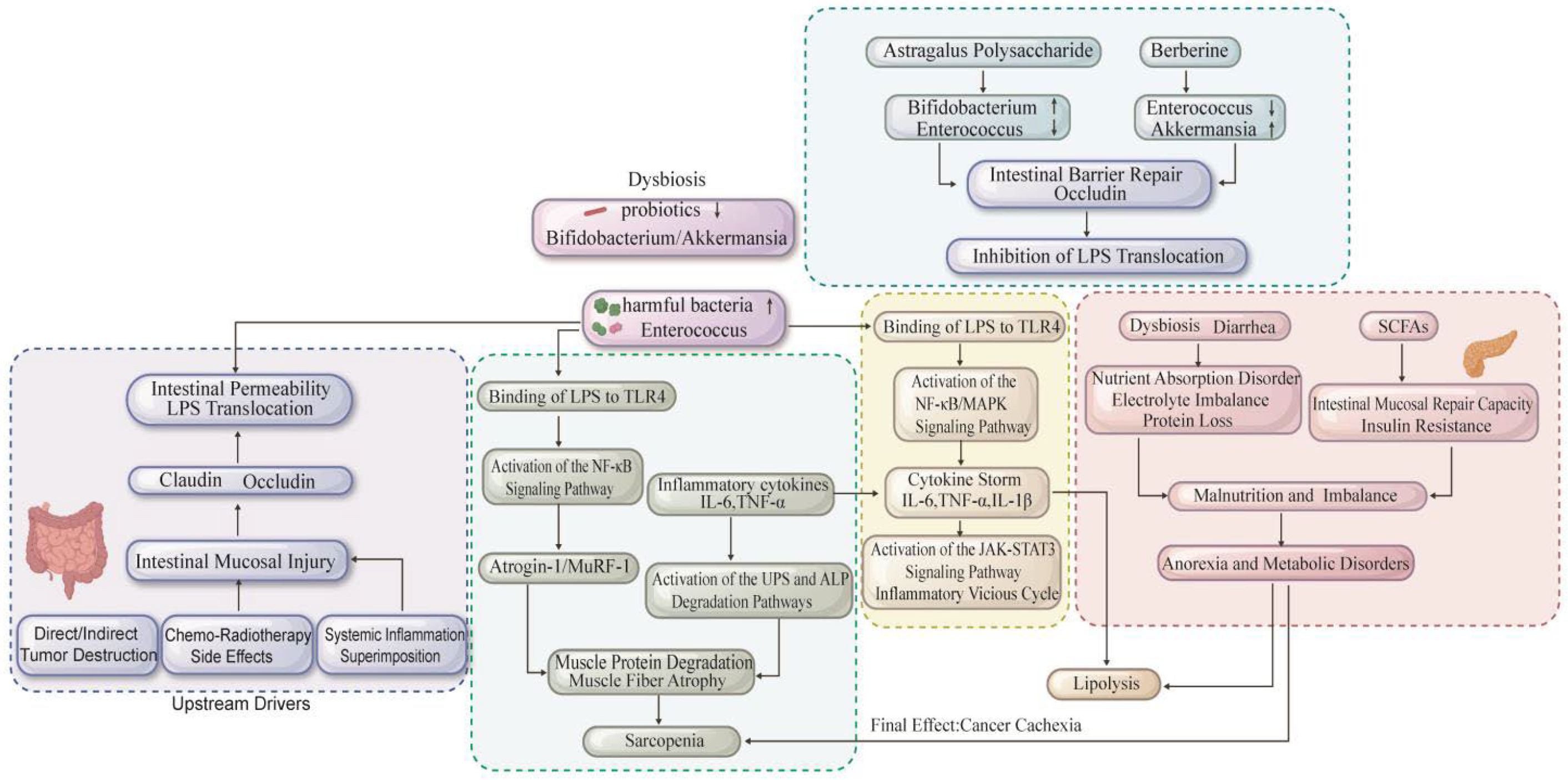

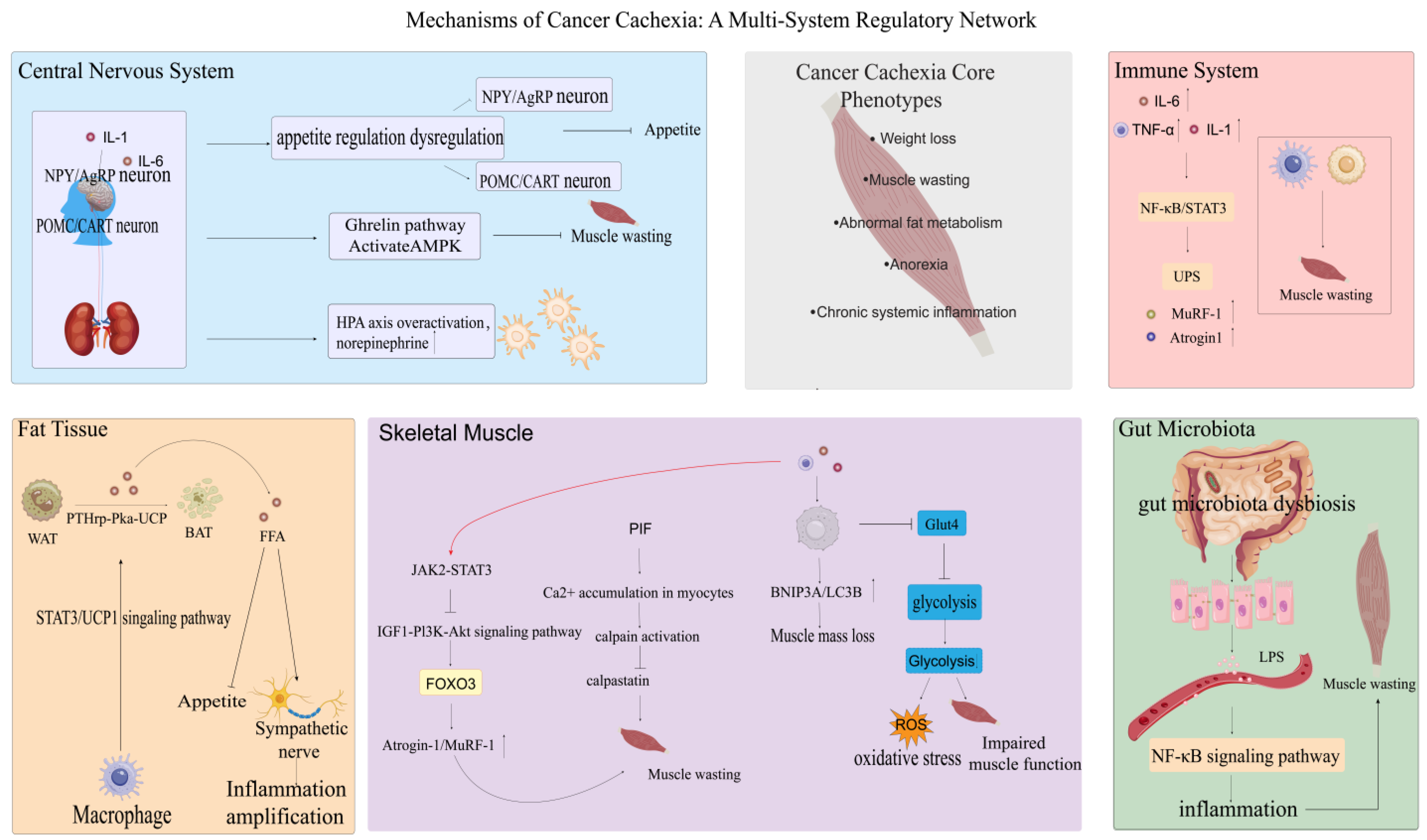

2. The Development of CC Involves Multiple Organs

2.1. Central Nervous System

2.2. Fat

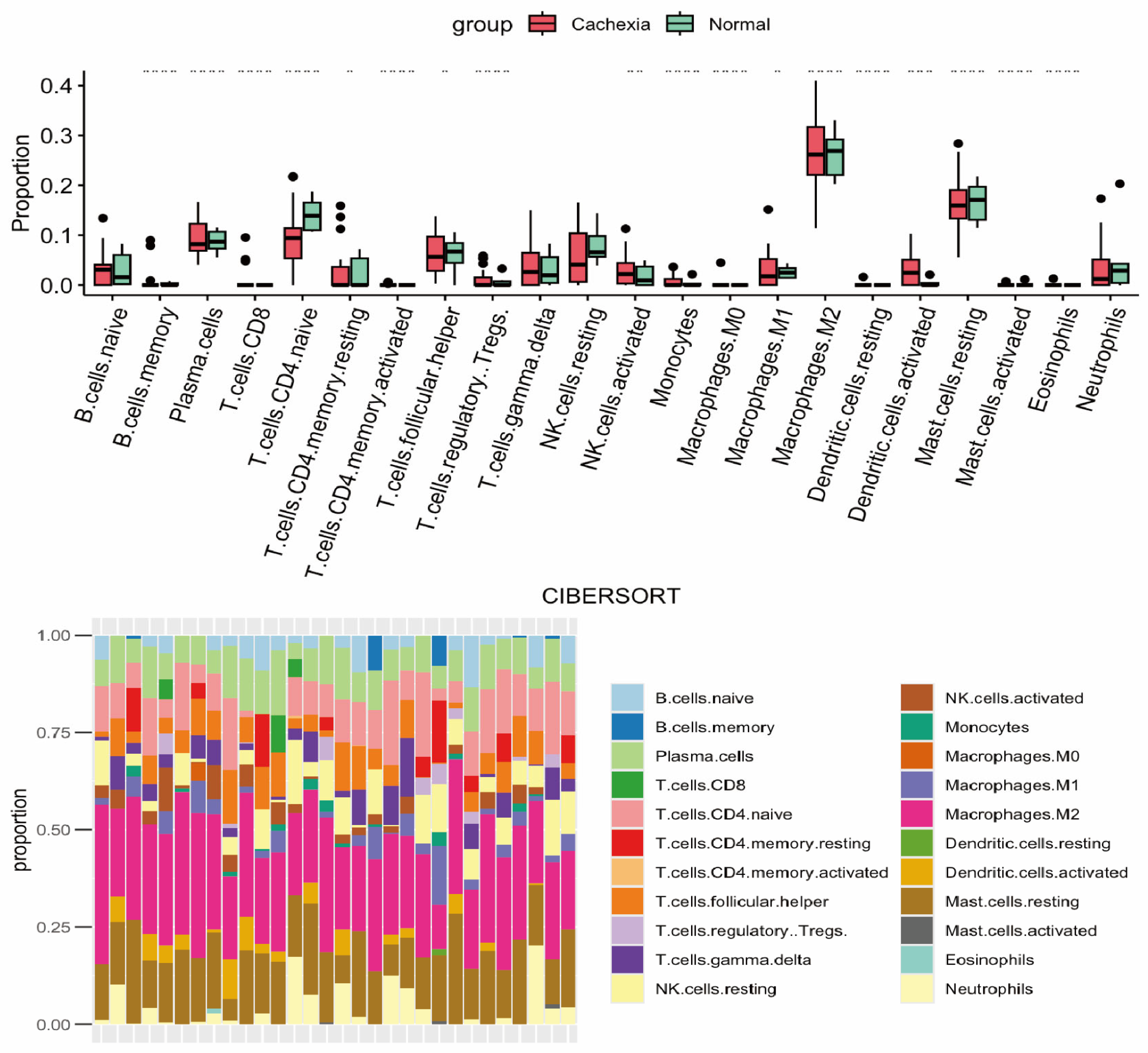

2.3. Immune System

2.4. Gut and Microbiota

2.5. Skeletal Muscle

3. Metabolic Dysregulation in CC

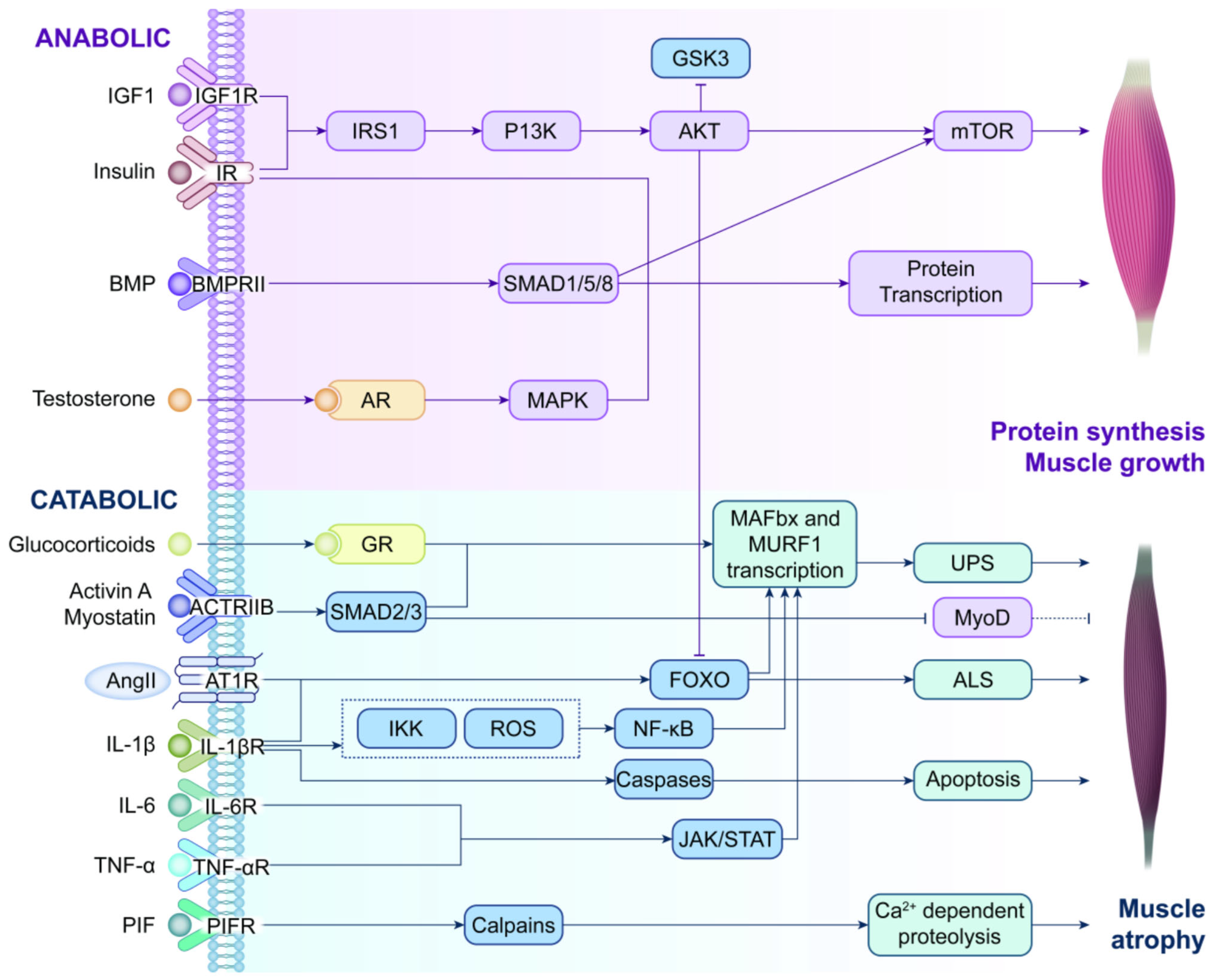

3.1. Anabolism

3.2. Catabolism

3.3. Emerging Regulators

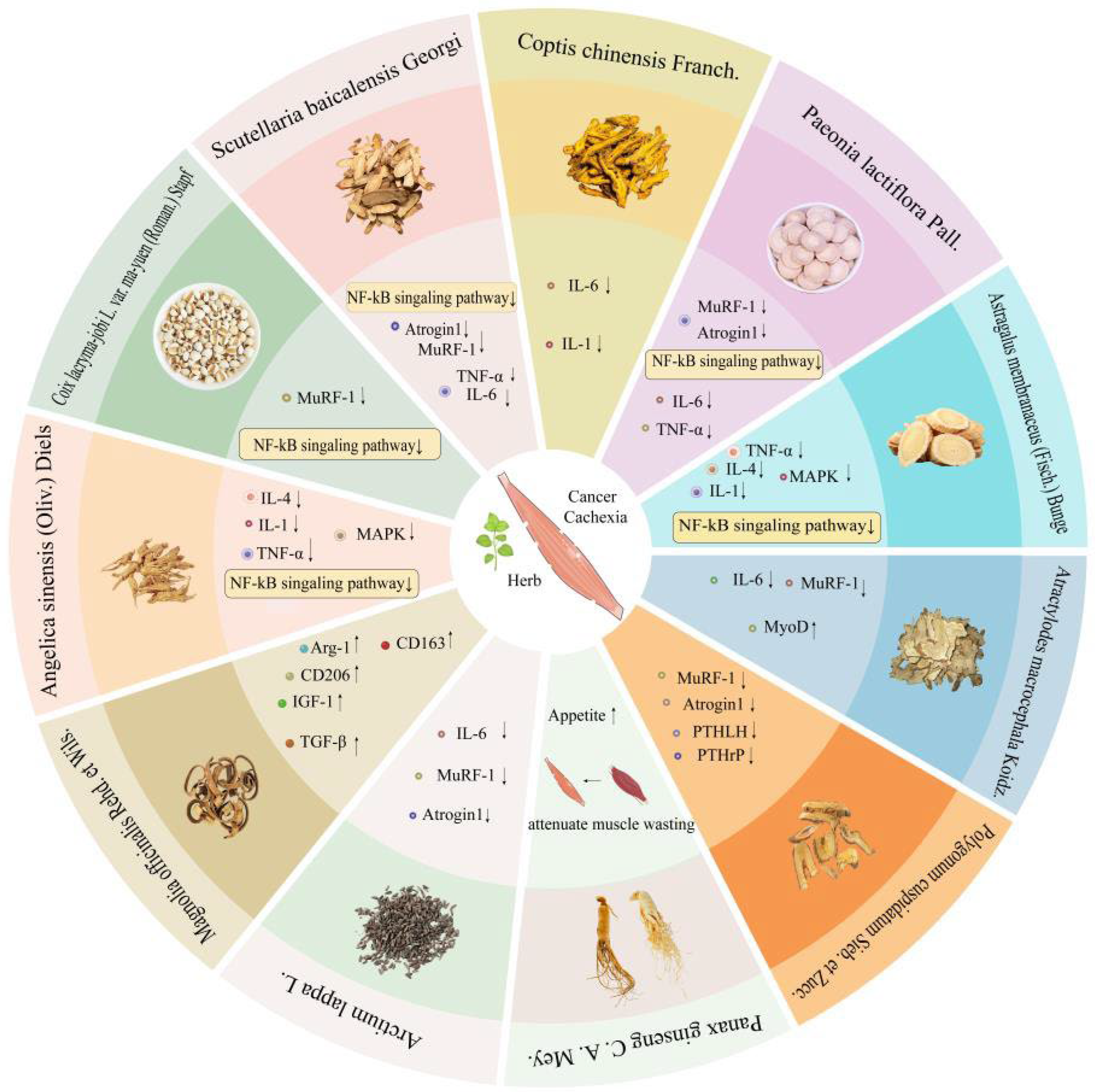

4. Natural Herbs for Cancer Malignancy Treatment

4.1. Coix lacryma-jobi L. var. ma-yuen (Roman.) Stapf

4.2. Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi

4.3. Coptis chinensis Franch

4.4. Paeonia lactiflora Pall. Pall.

4.5. Panax ginseng C. A. Mey

4.6. Astragalus membranaceus (Fisch.) Bunge

4.7. Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz

4.8. Polygonum cuspidatum Sieb. et Zucc.

4.9. Other Herbs

4.10. Future Perspectives and Cross-Herb Analysis

5. Comparison Between Conventional Treatment and Natural Herbal for Cancer Cachexia

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Relaix, F.; Bencze, M.; Borok, M.J.; Der Vartanian, A.; Gattazzo, F.; Mademtzoglou, D.; Perez-Diaz, S.; Prola, A.; Reyes-Fernandez, P.C.; Rotini, A.; et al. Perspectives on skeletal muscle stem cells. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blazev, R.; Ashwood, C.; Abrahams, J.L.; Chung, L.H.; Francis, D.; Yang, P.; Watt, K.I.; Qian, H.; Quaife-Ryan, G.A.; Hudson, J.E.; et al. Integrated Glycoproteomics Identifies a Role of N-Glycosylation and Galectin-1 on Myogenesis and Muscle Development. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2021, 20, 100030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorgenson, K.W.; Phillips, S.M.; Hornberger, T.A. Identifying the Structural Adaptations that Drive the Mechanical Load-Induced Growth of Skeletal Muscle: A Scoping Review. Cells 2020, 9, 1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Zhang, T.; Shao, W.; Lu, R.; Wang, L.; Liu, H.; Jiang, B.; Li, S.; Zhuo, H.; Wang, S.; et al. Amiloride ameliorates muscle wasting in cancer cachexia through inhibiting tumor-derived exosome release. Skelet. Muscle 2021, 11, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coudert, L.; Osseni, A.; Gangloff, Y.G.; Schaeffer, L.; Leblanc, P. The ESCRT-0 subcomplex component Hrs/Hgs is a master regulator of myogenesis via modulation of signaling and degradation pathways. BMC Biol. 2021, 19, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukuya, T.; Takahashi, K.; Shintani, Y.; Miura, K.; Sekine, I.; Takayama, K.; Inoue, A.; Okamoto, I.; Kiura, K.; Kawaguchi, T.; et al. Epidemiology, risk factors and impact of cachexia on patient outcome: Results from the Japanese Lung Cancer Registry Study. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2023, 14, 1274–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, H.; Oshima, T. The Latest Treatments for Cancer Cachexia: An Overview. Anticancer Res. 2023, 43, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibaut, M.M.; Sboarina, M.; Roumain, M.; Pötgens, S.A.; Neyrinck, A.M.; Destrée, F.; Gillard, J.; Leclercq, I.A.; Dachy, G.; Demoulin, J.B.; et al. Inflammation-induced cholestasis in cancer cachexia. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2021, 12, 70–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammucari, C.; Gherardi, G.; Zamparo, I.; Raffaello, A.; Boncompagni, S.; Chemello, F.; Cagnin, S.; Braga, A.; Zanin, S.; Pallafacchina, G.; et al. The mitochondrial calcium uniporter controls skeletal muscle trophism in vivo. Cell Rep. 2015, 10, 1269–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szondy, Z.; Al-Zaeed, N.; Tarban, N.; Fige, É.; Garabuczi, É.; Sarang, Z. Involvement of phosphatidylserine receptors in the skeletal muscle regeneration: Therapeutic implications. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2022, 13, 1961–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jager-Wittenaar, H.; Dijkstra, P.U.; Dijkstra, G.; Bijzet, J.; Langendijk, J.A.; van der Laan, B.; Roodenburg, J.L.N. High prevalence of cachexia in newly diagnosed head and neck cancer patients: An exploratory study. Nutrition 2017, 35, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, S.A.; Dasgupta, A.; Doles, J.D. Promising preclinical approaches to combating cancer-associated cachexia/tissue wasting. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 2025, 19, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearon, K.; Strasser, F.; Anker, S.D.; Bosaeus, I.; Bruera, E.; Fainsinger, R.L.; Jatoi, A.; Loprinzi, C.; MacDonald, N.; Mantovani, G.; et al. Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: An international consensus. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, M.; Anthony, T.G.; Ayres, J.S.; Biffi, G.; Brown, J.C.; Caan, B.J.; Cespedes Feliciano, E.M.; Coll, A.P.; Dunne, R.F.; Goncalves, M.D.; et al. Cachexia: A systemic consequence of progressive, unresolved disease. Cell 2023, 186, 1824–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Setiawan, T.; Sari, I.N.; Wijaya, Y.T.; Julianto, N.M.; Muhammad, J.A.; Lee, H.; Chae, J.H.; Kwon, H.Y. Cancer cachexia: Molecular mechanisms and treatment strategies. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2023, 16, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Li, X.; Jiao, D.; Cai, Y.; Qian, L.; Shen, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Fu, B.; Sun, R.; et al. LCN2 secreted by tissue-infiltrating neutrophils induces the ferroptosis and wasting of adipose and muscle tissues in lung cancer cachexia. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2023, 16, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tołoczko-Iwaniuk, N.; Dziemiańczyk-Pakieła, D.; Nowaszewska, B.K.; Celińska-Janowicz, K.; Miltyk, W. Celecoxib in Cancer Therapy and Prevention—Review. Curr. Drug Targets 2019, 20, 302–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Wu, J.; Zhang, X.; Zou, X.; Li, C.; Wang, H.; Yuan, M.; Chen, M.; Sun, Q.; Liu, S. Modified Bu-zhong-yi-qi decoction synergies with 5 fluorouracile to inhibits gastric cancer progress via PD-1/PD- L1-dependent T cell immunization. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 152, 104623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddocks, M. Physical activity and exercise training in cancer patients. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2020, 40, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortiula, F.; Hendriks, L.E.L.; van de Worp, W.; Schols, A.; Vaes, R.D.W.; Langen, R.C.J.; De Ruysscher, D. Physical exercise at the crossroad between muscle wasting and the immune system: Implications for lung cancer cachexia. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2022, 13, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Garcia, V.; López-Briz, E.; Carbonell Sanchis, R.; Gonzalvez Perales, J.L.; Bort-Marti, S. Megestrol acetate for treatment of anorexia-cachexia syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2013, Cd004310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-García, V.; López-Briz, E.; Carbonell-Sanchis, R.; Bort-Martí, S.; Gonzálvez-Perales, J.L. Megestrol acetate for cachexia-anorexia syndrome. A systematic review. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2018, 9, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, H.; Asakawa, A.; Amitani, H.; Nakamura, N.; Inui, A. Cachexia and herbal medicine: Perspective. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2012, 18, 4865–4888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.; You, S.; Cho, W.C.S.; Choi, J.Y.; Lee, M.S. A systematic review of herbal medicines for the treatment of cancer cachexia in animal models. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2019, 20, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Qiu, H.; Li, C.; Cai, P.; Qi, F. The positive role of traditional Chinese medicine as an adjunctive therapy for cancer. Biosci. Trends 2021, 15, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Wang, N.; Yang, R.; Wu, Y.; Liu, J.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Chan, Y.T.; et al. Efficacy and safety of herbal medicines intervention for cachexia associated with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Phytother. Res. 2023, 37, 5243–5278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khayri, J.M.; Sahana, G.R.; Nagella, P.; Joseph, B.V.; Alessa, F.M.; Al-Mssallem, M.Q. Flavonoids as Potential Anti-Inflammatory Molecules: A Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankovic, B.; Bjørhovde, H.A.K.; Skarshaug, R.; Aamodt, H.; Frafjord, A.; Müller, E.; Hammarström, C.; Beraki, K.; Bækkevold, E.S.; Woldbæk, P.R.; et al. Immune Cell Composition in Human Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 3101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compton, S.L.E.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Brown, J.C. Nutritional Mechanisms of Cancer Cachexia. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2024, 44, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, R.; da Fonseca, G.W.P.; das Neves, W.; von Haehling, S. Mechanisms and pharmacotherapy of cancer cachexia-associated anorexia. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2025, 13, e70031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakir, T.M.; Wang, A.R.; Decker-Farrell, A.R.; Ferrer, M.; Guin, R.N.; Kleeman, S.; Levett, L.; Zhao, X.; Janowitz, T. Cancer therapy and cachexia. J. Clin. Investig. 2025, 135, e191934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baracos, V.E.; Martin, L.; Korc, M.; Guttridge, D.C.; Fearon, K.C.H. Cancer-associated cachexia. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 17105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inui, A. Cancer anorexia-cachexia syndrome: Are neuropeptides the key? Cancer Res. 1999, 59, 4493–4501. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Wang, X.; Deng, L. Analysis of Acupoints Combination for Cancer-Related Anorexia Based on Association Rule Mining. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2022, 2022, 4251458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishii, H.; Wada, M.; Furuya, Y.; Nagano, N.; Nemeth, E.F.; Fox, J. Daily intermittent decreases in serum levels of parathyroid hormone have an anabolic-like action on the bones of uremic rats with low-turnover bone and osteomalacia. Bone 2000, 26, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sędzikowska, A.; Szablewski, L. Insulin and Insulin Resistance in Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Norren, K.; Dwarkasing, J.T.; Witkamp, R.F. The role of hypothalamic inflammation, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and serotonin in the cancer anorexia-cachexia syndrome. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2017, 20, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, F. Neuropsychiatric aspects of deficiency manifestations associated with digestive & neuro-endocrine disorders. IV. Lesions of the nervous system in a case of cachexia due to starvation. Psychiatr. Neurol. 1958, 135, 247–260. [Google Scholar]

- Burfeind, K.G.; Michaelis, K.A.; Marks, D.L. The central role of hypothalamic inflammation in the acute illness response and cachexia. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2016, 54, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pobłocki, J.; Jasińska, A.; Syrenicz, A.; Andrysiak-Mamos, E.; Szczuko, M. The Neuroendocrine Neoplasms of the Digestive Tract: Diagnosis, Treatment and Nutrition. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razolli, D.S.; de Araújo, T.M.; Sant Apos Ana, M.R.; Kirwan, P.; Cintra, D.E.; Merkle, F.T.; Velloso, L.A. Proopiomelanocortin Processing in the Hypothalamus Is Directly Regulated by Saturated Fat: Implications for the Development of Obesity. Neuroendocrinology 2020, 110, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, M.C.; Pimentel, G.D.; Costa, F.O.; Carvalheira, J.B. Molecular and neuroendocrine mechanisms of cancer cachexia. J. Endocrinol. 2015, 226, R29–R43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, B.; Diba, P.; Korzun, T.; Marks, D.L. Neural Mechanisms of Cancer Cachexia. Cancers 2021, 13, 3990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro, I.B.K.; Schraner, M.; Riediger, T. Brainstem prolactin-releasing peptide contributes to cancer anorexia-cachexia syndrome in rats. Neuropharmacology 2020, 180, 108289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Callahan, M.F.; Gruber, K.A.; Szumowski, M.; Marks, D.L. Melanocortin-4 receptor antagonist TCMCB07 ameliorates cancer- and chronic kidney disease-associated cachexia. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 4921–4934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petruzzelli, M.; Wagner, E.F. Mechanisms of metabolic dysfunction in cancer-associated cachexia. Genes Dev. 2016, 30, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadpour, H.; MacDonald, C.R.; Qiao, G.; Chen, M.; Dong, B.; Hylander, B.L.; McCarthy, P.L.; Abrams, S.I.; Repasky, E.A. β2 adrenergic receptor-mediated signaling regulates the immunosuppressive potential of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 5537–5552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Kong, Q.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Hua, H. Complex roles of cAMP-PKA-CREB signaling in cancer. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 9, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szarka, L.A.; Camilleri, M. Gastric emptying. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2009, 7, 823–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Jin, Y.; Yuan, K.; Liu, B.; Zhu, N.; Zhang, K.; Li, S.; Tai, Z. Effects of exosomes and inflammatory response on tumor: A bibliometrics study and visualization analysis via CiteSpace and VOSviewer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 150, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood-Van Meerveld, B.; Johnson, A.C.; Grundy, D. Gastrointestinal Physiology and Function. In Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 239, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakawa, A.; Fujimiya, M.; Niijima, A.; Fujino, K.; Kodama, N.; Sato, Y.; Kato, I.; Nanba, H.; Laviano, A.; Meguid, M.M.; et al. Parathyroid hormone-related protein has an anorexigenic activity via activation of hypothalamic urocortins 2 and 3. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2010, 35, 1178–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, H.; Goto, M.; Fukunishi, S.; Asai, A.; Nishiguchi, S.; Higuchi, K. Cancer Cachexia: Its Mechanism and Clinical Significance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otto, A.K.; Ketcher, D.; Reblin, M.; Terrill, A.L. Positive Psychology Approaches to Interventions for Cancer Dyads: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res Public Health 2022, 19, 13561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Zhou, X.; Sun, M.; Yu, N.X.; Peng, Y.; Zheng, X.; Xiao, W. The effectiveness of positive psychological interventions for patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Nurs. 2024, 33, 3752–3774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanagi, S.; Sato, T.; Kangawa, K.; Nakazato, M. The Homeostatic Force of Ghrelin. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 786–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixit, V.D.; Schaffer, E.M.; Pyle, R.S.; Collins, G.D.; Sakthivel, S.K.; Palaniappan, R.; Lillard, J.W., Jr.; Taub, D.D. Ghrelin inhibits leptin- and activation-induced proinflammatory cytokine expression by human monocytes and T cells. J. Clin. Investig. 2004, 114, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porporato, P.E.; Filigheddu, N.; Reano, S.; Ferrara, M.; Angelino, E.; Gnocchi, V.F.; Prodam, F.; Ronchi, G.; Fagoonee, S.; Fornaro, M.; et al. Acylated and unacylated ghrelin impair skeletal muscle atrophy in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heppner, K.M.; Piechowski, C.L.; Müller, A.; Ottaway, N.; Sisley, S.; Smiley, D.L.; Habegger, K.M.; Pfluger, P.T.; Dimarchi, R.; Biebermann, H.; et al. Both acyl and des-acyl ghrelin regulate adiposity and glucose metabolism via central nervous system ghrelin receptors. Diabetes 2014, 63, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Busino, L. E3 ubiquitin ligases in B-cell malignancies. Cell Immunol. 2019, 340, 103905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulei, D.; Drula, R.; Ghiaur, G.; Buzoianu, A.D.; Kravtsova-Ivantsiv, Y.; Tomuleasa, C.; Ciechanover, A. The Tumor Suppressor Functions of Ubiquitin Ligase KPC1: From Cell-Cycle Control to NF-κB Regulator. Cancer Res. 2023, 83, 1762–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, V.P.; Moglad, E.; Afzal, M.; Kazmi, I.; Alzarea, S.I.; Ali, H.; Almujri, S.S.; Abida; Imran, M.; Gupta, G.; et al. Exploring Ubiquitin-specific proteases as therapeutic targets in Glioblastoma. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2024, 260, 155443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.A.; Splenser, A.; Guillory, B.; Luo, J.; Mendiratta, M.; Belinova, B.; Halder, T.; Zhang, G.; Li, Y.P.; Garcia, J.M. Ghrelin prevents tumour- and cisplatin-induced muscle wasting: Characterization of multiple mechanisms involved. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2015, 6, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu, Y.; Overby, H.; Ren, G.; Fan, Z.; Zhao, L.; Wang, S. Resveratrol liposomes and lipid nanocarriers: Comparison of characteristics and inducing browning of white adipocytes. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2018, 164, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molfino, A.; Carletti, R.; Imbimbo, G.; Amabile, M.I.; Belli, R.; di Gioia, C.R.T.; Belloni, E.; Spinelli, F.; Rizzo, V.; Catalano, C.; et al. Histomorphological and inflammatory changes of white adipose tissue in gastrointestinal cancer patients with and without cachexia. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2022, 13, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Fatima Silva, F.; de Morais, H.; Ortiz Silva, M.; da Silva, F.G.; Vianna Croffi, R.; Serrano-Nascimento, C.; Rodrigues Graciano, M.F.; Rafael Carpinelli, A.; Barbosa Bazotte, R.; de Souza, H.M. Akt activation by insulin treatment attenuates cachexia in Walker-256 tumor-bearing rats. J. Cell Biochem. 2020, 121, 4558–4568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, S.A.; Pasquarelli-do-Nascimento, G.; da Silva, D.S.; Farias, G.R.; de Oliveira Santos, I.; Baptista, L.B.; Magalhães, K.G. Browning of the white adipose tissue regulation: New insights into nutritional and metabolic relevance in health and diseases. Nutr. Metab. 2022, 19, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henriques, F.; Bedard, A.H.; Guilherme, A.; Kelly, M.; Chi, J.; Zhang, P.; Lifshitz, L.M.; Bellvé, K.; Rowland, L.A.; Yenilmez, B.; et al. Single-Cell RNA Profiling Reveals Adipocyte to Macrophage Signaling Sufficient to Enhance Thermogenesis. Cell Rep. 2020, 32, 107998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, S.; Wang, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Lei, J.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wu, L.; Zhou, M.; et al. Integrated LC-MS metabolomics with dual derivatization for quantification of FFAs in fecal samples of hepatocellular carcinoma patients. J. Lipid Res. 2021, 62, 100143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangano, G.D.; Fouani, M.; D’Amico, D.; Di Felice, V.; Barone, R. Cancer-Related Cachexia: The Vicious Circle between Inflammatory Cytokines, Skeletal Muscle, Lipid Metabolism and the Possible Role of Physical Training. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Moylan, J.S.; Chambers, M.A.; Smith, J.; Reid, M.B. Interleukin-1 stimulates catabolism in C2C12 myotubes. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2009, 297, C706–C714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghu, H.; Lepus, C.M.; Wang, Q.; Wong, H.H.; Lingampalli, N.; Oliviero, F.; Punzi, L.; Giori, N.J.; Goodman, S.B.; Chu, C.R.; et al. CCL2/CCR2, but not CCL5/CCR5, mediates monocyte recruitment, inflammation and cartilage destruction in osteoarthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2017, 76, 914–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.X.; Zhang, S.X.; Wu, H.J.; Rong, X.L.; Guo, J. M2b macrophage polarization and its roles in diseases. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2019, 106, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutilier, A.J.; Elsawa, S.F. Macrophage Polarization States in the Tumor Microenvironment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, A.; Tiwari, S.; Lee, P.; Ndisang, J.F. The heme oxygenase system selectively enhances the anti-inflammatory macrophage-M2 phenotype, reduces pericardial adiposity, and ameliorated cardiac injury in diabetic cardiomyopathy in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2013, 345, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuenca, A.G.; Cuenca, A.L.; Winfield, R.D.; Joiner, D.N.; Gentile, L.; Delano, M.J.; Kelly-Scumpia, K.M.; Scumpia, P.O.; Matheny, M.K.; Scarpace, P.J.; et al. Novel role for tumor-induced expansion of myeloid-derived cells in cancer cachexia. J. Immunol. 2014, 192, 6111–6119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, I.J.; Stephens, N.A.; MacDonald, A.J.; Skipworth, R.J.; Husi, H.; Greig, C.A.; Ross, J.A.; Timmons, J.A.; Fearon, K.C. Suppression of skeletal muscle turnover in cancer cachexia: Evidence from the transcriptome in sequential human muscle biopsies. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 2817–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, Y.; Shirure, V.S.; Liu, R.; Cunningham, C.; Ding, L.; Meacham, J.M.; Goedegebuure, S.P.; George, S.C.; Fields, R.C. Tumor-on-a-chip platform to interrogate the role of macrophages in tumor progression. Integr. Biol. 2020, 12, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, U.; Sarkar, T.; Mukherjee, S.; Chakraborty, S.; Dutta, A.; Dutta, S.; Nayak, D.; Kaushik, S.; Das, T.; Sa, G. Tumor-associated macrophages: An effective player of the tumor microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1295257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, R.; Lo, B.C.; Núñez, G. Host-microbiota interactions in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, C.A.; Diaz-Arteche, C.; Eliby, D.; Schwartz, O.S.; Simmons, J.G.; Cowan, C.S.M. The gut microbiota in anxiety and depression—A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 83, 101943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victoria, M.; Elena, V.B.; Amparo, G.N.; María, J.A.; Adriana, G.V.; Irene, A.C.; Alejandra, Y.M.; Janeth, B.B.; María, A.G. Gut microbiota alterations in critically ill older patients: A multicenter study. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIllmurray, M.B.; Price, M.R.; Langman, M.J. Inhibition of leucocyte migration in patients with large intestinal cancer by extracts prepared from large intestinal tumours and from normal colonic mucosa. Br. J. Cancer 1974, 29, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herremans, K.M.; Riner, A.N.; Cameron, M.E.; Trevino, J.G. The Microbiota and Cancer Cachexia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 6267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bindels, L.B.; Neyrinck, A.M.; Loumaye, A.; Catry, E.; Walgrave, H.; Cherbuy, C.; Leclercq, S.; Van Hul, M.; Plovier, H.; Pachikian, B.; et al. Increased gut permeability in cancer cachexia: Mechanisms and clinical relevance. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 18224–18238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Peng, X.H.; Wang, L.Y.; Wang, A.B.; Su, Y.Y.; Chen, J.H.; Zhang, X.W.; Zhao, D.Z.; Wang, H.; Pang, D.X.; et al. Abnormality of intestinal cholesterol absorption in Apc(Min/+) mice with colon cancer cachexia. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2019, 12, 759–767. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, W.; Wong, C.C.; Song, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Q.; Ren, X.; Ren, X.; Xuan, R.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Catenibacteriummitsuokai promotes hepatocellular carcinogenesis by binding to hepatocytes and generating quinolinic acid. Cell Metab. 2025, 37, 1998–2013.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effenberger, M.; Grander, C.; Grabherr, F.; Tilg, H. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and the Intestinal Microbiome: An Inseparable Link. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2023, 11, 1498–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Shi, X. Big lessons from the little Akkermansia muciniphila in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1524563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostosi, D.; Molinaro, M.; Saccone, S.; Torrente, Y.; Villa, C.; Farini, A. Exploring the Gut Microbiota-Muscle Axis in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Hu, H.; Liang, X.; Liang, J.; Li, F.; Zhou, X. Gut microbes-muscle axis in muscle function and meat quality. Sci. China Life Sci. 2025, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephens, N.A.; Gray, C.; MacDonald, A.J.; Tan, B.H.; Gallagher, I.J.; Skipworth, R.J.; Ross, J.A.; Fearon, K.C.; Greig, C.A. Sexual dimorphism modulates the impact of cancer cachexia on lower limb muscle mass and function. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 31, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaldo, P.; Sandri, M. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of muscle atrophy. Dis. Model. Mech. 2013, 6, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pin, F.; Minero, V.G.; Penna, F.; Muscaritoli, M.; De Tullio, R.; Baccino, F.M.; Costelli, P. Interference with Ca(2+)-Dependent Proteolysis Does Not Alter the Course of Muscle Wasting in Experimental Cancer Cachexia. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitajima, Y.; Yoshioka, K.; Suzuki, N. The ubiquitin-proteasome system in regulation of the skeletal muscle homeostasis and atrophy: From basic science to disorders. J. Physiol. Sci. 2020, 70, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, D.; Frantz, J.D.; Tawa, N.E., Jr.; Melendez, P.A.; Oh, B.C.; Lidov, H.G.; Hasselgren, P.O.; Frontera, W.R.; Lee, J.; Glass, D.J.; et al. IKKbeta/NF-kappaB activation causes severe muscle wasting in mice. Cell 2004, 119, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaisari, S.; Rom, O.; Aizenbud, D.; Reznick, A.Z. Involvement of NF-κB and muscle specific E3 ubiquitin ligase MuRF1 in cigarette smoke-induced catabolism in C2 myotubes. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2013, 788, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tardif, N.; Klaude, M.; Lundell, L.; Thorell, A.; Rooyackers, O. Autophagic-lysosomal pathway is the main proteolytic system modified in the skeletal muscle of esophageal cancer patients. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 98, 1485–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganapathy-Kanniappan, S.; Geschwind, J.F. Tumor glycolysis as a target for cancer therapy: Progress and prospects. Mol. Cancer 2013, 12, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costelli, P.; De Tullio, R.; Baccino, F.M.; Melloni, E. Activation of Ca(2+)-dependent proteolysis in skeletal muscle and heart in cancer cachexia. Br. J. Cancer 2001, 84, 946–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dargelos, E.; Brulé, C.; Combaret, L.; Hadj-Sassi, A.; Dulong, S.; Poussard, S.; Cottin, P. Involvement of the calcium-dependent proteolytic system in skeletal muscle aging. Exp. Gerontol. 2007, 42, 1088–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, K.A.; Tisdale, M.J. Role of Ca2+ in proteolysis-inducing factor (PIF)-induced atrophy of skeletal muscle. Cell Signal 2012, 24, 2118–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhfi, F.Z.; Al Amin, M.; Zehravi, M.; Sweilam, S.H.; Arjun, U.; Gupta, J.K.; Vallamkonda, B.; Balakrishnan, A.; Challa, M.; Singh, J.; et al. Alkaloid-based modulators of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway for cancer therapy: Understandings from pharmacological point of view. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2024, 402, 111218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentzinger, C.F.; Romanino, K.; Cloëtta, D.; Lin, S.; Mascarenhas, J.B.; Oliveri, F.; Xia, J.; Casanova, E.; Costa, C.F.; Brink, M.; et al. Skeletal muscle-specific ablation of raptor, but not of rictor, causes metabolic changes and results in muscle dystrophy. Cell Metab. 2008, 8, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.; Sitzmann, J.M.; Dastidar, S.G.; Rodriguez, A.A.; Vu, S.L.; McDonald, C.E.; Academia, E.C.; O’Leary, M.N.; Ashe, T.D.; La Spada, A.R.; et al. Muscle-specific 4E-BP1 signaling activation improves metabolic parameters during aging and obesity. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 125, 2952–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Inoki, K.; Brooks, S.V.; Okazawa, H.; Lee, M.; Wang, J.; Kim, M.; Kennedy, C.L.; Macpherson, P.C.D.; Ji, X.; et al. mTORC1 underlies age-related muscle fiber damage and loss by inducing oxidative stress and catabolism. Aging Cell 2019, 18, e12943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, A.S.; Chojnowska, K.; Tintignac, L.A.; Lin, S.; Schmidt, A.; Ham, D.J.; Sinnreich, M.; Rüegg, M.A. mTORC1 signalling is not essential for the maintenance of muscle mass and function in adult sedentary mice. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2020, 11, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamming, D.W.; Ye, L.; Katajisto, P.; Goncalves, M.D.; Saitoh, M.; Stevens, D.M.; Davis, J.G.; Salmon, A.B.; Richardson, A.; Ahima, R.S.; et al. Rapamycin-induced insulin resistance is mediated by mTORC2 loss and uncoupled from longevity. Science 2012, 335, 1638–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, J.P.; Puppa, M.J.; Gao, S.; Sato, S.; Welle, S.L.; Carson, J.A. Muscle mTORC1 suppression by IL-6 during cancer cachexia: A role for AMPK. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 304, E1042–E1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.J.; Schneider, M.F. Alternative signaling pathways from IGF1 or insulin to AKT activation and FOXO1 nuclear efflux in adult skeletal muscle fibers. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 15292–15306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakai, H.; Asami, M.; Naito, H.; Kitora, S.; Suzuki, Y.; Miyauchi, Y.; Tachinooka, R.; Yoshida, S.; Kon, R.; Ikarashi, N.; et al. Exogenous insulin-like growth factor 1 attenuates cisplatin-induced muscle atrophy in mice. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2021, 12, 1570–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Li, N.; Zhu, W.; Li, W.; Tang, S.; Yu, W.; Gao, T.; Zhang, J.; Li, J. Insulin alleviates degradation of skeletal muscle protein by inhibiting the ubiquitin-proteasome system in septic rats. J. Inflamm. 2011, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, R.; Qu, X. Mechanisms of insulin resistance and new pharmacological approaches to metabolism and diabetic complications. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 1998, 25, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado-Neto, J.A.; Fenerich, B.A.; Rodrigues Alves, A.P.N.; Fernandes, J.C.; Scopim-Ribeiro, R.; Coelho-Silva, J.L.; Traina, F. Insulin Substrate Receptor (IRS) proteins in normal and malignant hematopoiesis. Clinics 2018, 73, e566s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dev, R.; Bruera, E.; Dalal, S. Insulin resistance and body composition in cancer patients. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, ii18–ii26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Kundu, M.; Viollet, B.; Guan, K.L. AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011, 13, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Ding, S. Unraveling the role of STAT3 in Cancer Cachexia: Pathogenic mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1608612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.L.; Walton, K.L.; Winbanks, C.E.; Murphy, K.T.; Thomson, R.E.; Makanji, Y.; Qian, H.; Lynch, G.S.; Harrison, C.A.; Gregorevic, P. Elevated expression of activins promotes muscle wasting and cachexia. FASEB J. 2014, 28, 1711–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherron, A.C.; Lawler, A.M.; Lee, S.J. Regulation of skeletal muscle mass in mice by a new TGF-beta superfamily member. Nature 1997, 387, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenk, K.; Schuler, G.; Adams, V. Skeletal muscle wasting in cachexia and sarcopenia: Molecular pathophysiology and impact of exercise training. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2010, 1, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartori, R.; Milan, G.; Patron, M.; Mammucari, C.; Blaauw, B.; Abraham, R.; Sandri, M. Smad2 and 3 transcription factors control muscle mass in adulthood. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2009, 296, C1248–C1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira-Pais, A.; Ferreira, R.; Oliveira, P.A.; Duarte, J.A. Sarcopenia versus cancer cachexia: The muscle wasting continuum in healthy and diseased aging. Biogerontology 2021, 22, 459–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.P.; Schwartz, R.J.; Waddell, I.D.; Holloway, B.R.; Reid, M.B. Skeletal muscle myocytes undergo protein loss and reactive oxygen-mediated NF-kappaB activation in response to tumor necrosis factor alpha. FASEB J. 1998, 12, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kami, K.; Senba, E. In vivo activation of STAT3 signaling in satellite cells and myofibers in regenerating rat skeletal muscles. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2002, 50, 1579–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thoma, A.; Lightfoot, A.P. NF-kB and Inflammatory Cytokine Signalling: Role in Skeletal Muscle Atrophy. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018, 1088, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Marco, S.; Mazroui, R.; Dallaire, P.; Chittur, S.; Tenenbaum, S.A.; Radzioch, D.; Marette, A.; Gallouzi, I.E. NF-kappa B-mediated MyoD decay during muscle wasting requires nitric oxide synthase mRNA stabilization, HuR protein, and nitric oxide release. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005, 25, 6533–6545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.P.; Chen, Y.; John, J.; Moylan, J.; Jin, B.; Mann, D.L.; Reid, M.B. TNF-alpha acts via p38 MAPK to stimulate expression of the ubiquitin ligase atrogin1/MAFbx in skeletal muscle. FASEB J. 2005, 19, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.F.; Sanchez, B.J.; Hall, D.T.; Tremblay, A.K.; Di Marco, S.; Gallouzi, I.E. STAT3 promotes IFNγ/TNFα-induced muscle wasting in an NF-κB-dependent and IL-6-independent manner. EMBO Mol. Med. 2017, 9, 622–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasembeli, M.M.; Bharadwaj, U.; Robinson, P.; Tweardy, D.J. Contribution of STAT3 to Inflammatory and Fibrotic Diseases and Prospects for its Targeting for Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Wang, M.; Wu, Z.; Jia, J.; Yang, T.; Yu, L. Research progress of circRNA in malignant tumour metabolic reprogramming. RNA Biol. 2023, 20, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Ye, F.; Luo, D.; Long, L.; Wang, Y.; Jin, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Han, D.; Chen, B.; et al. Exosomal circSIPA1L3-mediated intercellular communication contributes to glucose metabolic reprogramming and progression of triple negative breast cancer. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narala, V.R.; Narala, S.R.; Aiya Subramani, P.; Panati, K.; Kolliputi, N. Role of mitochondria in inflammatory lung diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1433961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oltean, H.; Robbins, C.; van Tulder, M.W.; Berman, B.M.; Bombardier, C.; Gagnier, J.J. Herbal medicine for low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 2014, Cd004504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balarastaghi, S.; Delirrad, M.; Jafari, A.; Majidi, M.; Sadeghi, M.; Zare-Zardini, H.; Karimi, G.; Ghorani-Azam, A. Potential benefits versus hazards of herbal therapy during pregnancy; a systematic review of available literature. Phytother. Res. 2022, 36, 824–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed, S.A.D.; Hanxing, L.; Fang, L.; Algradi, A.M.; Alradhi, M.; Safi, M.; Shumin, L. Integrated Chinese herbal medicine with Western Medicine versus Western Medicine in the effectiveness of primary hypertension treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 300, 115703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, L.; Zou, J.; Zhou, T.; Wang, B.; Sun, H.; Yu, S. Coix seed oil ameliorates cancer cachexia by counteracting muscle loss and fat lipolysis. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 19, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Wan, L.; Li, Y.; Yu, Q.; Chen, P.; Gan, R.; Yang, Q.; Han, Y.; Guo, C. Baicalin, a component of Scutellaria baicalensis, alleviates anorexia and inhibits skeletal muscle atrophy in experimental cancer cachexia. Tumour Biol. 2014, 35, 12415–12425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iizuka, N.; Hazama, S.; Yoshimura, K.; Yoshino, S.; Tangoku, A.; Miyamoto, K.; Okita, K.; Oka, M. Anticachectic effects of the natural herb Coptidis rhizoma and berberine on mice bearing colon 26/clone 20 adenocarcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 2002, 99, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.B.; Lee, J.S.; Moon, S.O.; Lee, H.D.; Yoon, Y.S.; Son, C.G. A standardized herbal combination of Astragalus membranaceus and Paeonia japonica, protects against muscle atrophy in a C26 colon cancer cachexia mouse model. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 267, 113470, Corrigendum in J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 344, 119496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2025.119496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobina, C.; Carai, M.A.; Loi, B.; Gessa, G.L.; Riva, A.; Cabri, W.; Petrangolini, G.; Morazzoni, P.; Colombo, G. Protective effect of Panax ginseng in cisplatin-induced cachexia in rats. Future Oncol. 2014, 10, 1203–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.H.; Yeh, K.Y.; Wang, C.H.; Wang, H.; Li, T.L.; Chan, Y.L.; Wu, C.J. The Combination of Astragalus membranaceus and Angelica sinensis Inhibits Lung Cancer and Cachexia through Its Immunomodulatory Function. J. Oncol. 2019, 2019, 9206951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.; Gu, X.; Zhang, W.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, R.; Fang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X. Atractylenolide I ameliorates cancer cachexia through inhibiting biogenesis of IL-6 and tumour-derived extracellular vesicles. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2022, 13, 2724–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.Q.; Kim, Y.S.; Lee, Y.M.; Lee, M.; Lim, W.J.; Yim, W.J.; Han, M.W.; Lim, J.H. Polygonum cuspidatum Extract (Pc-Ex) Containing Emodin Suppresses Lung Cancer-Induced Cachexia by Suppressing TCF4/TWIST1 Complex-Induced PTHrP Expression. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.H.; Mun, J.G.; Jeon, H.D.; Yoon, D.H.; Choi, B.M.; Kee, J.Y.; Hong, S.H. The Extract of Arctium lappa L. Fruit (Arctii Fructus) Improves Cancer-Induced Cachexia by Inhibiting Weight Loss of Skeletal Muscle and Adipose Tissue. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.; Han, I.H.; Choi, I.; Cha, N.; Kim, W.; Kim, S.K.; Bae, H. Magnoliae Cortex Alleviates Muscle Wasting by Modulating M2 Macrophages in a Cisplatin-Induced Sarcopenia Mouse Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Bai, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liu, D. Extraction, purification, structural characterization and bioactivities of polysaccharides from coix seed: A review. Food Chem. 2025, 492, 145396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.; Wang, X.; Dong, H.; Yu, J.; Li, T.; Wang, X. Coix Seed Oil Alleviates Hyperuricemia in Mice by Ameliorating Oxidative Stress and Intestinal Microbial Composition. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabás-Rivera, C.; Barranquero, C.; Martínez-Beamonte, R.; Navarro, M.A.; Surra, J.C.; Osada, J. Dietary squalene increases high density lipoprotein-cholesterol and paraoxonase 1 and decreases oxidative stress in mice. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Meng, X.; Tang, X.; Ren, L.; Liang, J. The effect of a coix seed oil injection on cancer pain relief. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, F.; Cheng, Y.; Li, Y.; Fan, Q.; Qu, R.; Fan, T.; Lv, Y.; Dai, J. Progress in Mechanistic Research and the Use of Traditional Chinese Medicine in Treating Malignant Pleural Effusion. Cancer Manag. Res. 2025, 17, 1377–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.P.; Huang, X.E.; Cao, J.; Lu, Y.Y.; Wu, X.Y.; Liu, J.; Xu, X.; Xiang, J.; Ye, L.H. Clinical safety and efficacy of Kanglaite® (Coix Seed Oil) injection combined with chemotherapy in treating patients with gastric cancer. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2012, 13, 5319–5321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Li, S.; Huang, L.; Jiang, X. Polyphenolic metabolites in Scutellaria baicalensis as potential candidate agents for the treatment of ischemic stroke. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1700164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, L.; Wan, M.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Sun, H.; Bi, K. Simultaneous determination of baicalin, wogonoside, baicalein, wogonin, oroxylin A and chrysin of Radix scutellariae extract in rat plasma by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2012, 70, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Zhang, H.; Salmani, J.M.; Fu, R.; Chen, B. Advances of wogonin, an extract from Scutellaria baicalensis, for the treatment of multiple tumors. Onco Targets Ther. 2016, 9, 2935–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.A.; Zhang, R.; Piao, M.J.; Chae, S.; Kim, H.S.; Park, J.H.; Jung, K.S.; Hyun, J.W. Baicalein inhibits oxidative stress-induced cellular damage via antioxidant effects. Toxicol. Ind. Health 2012, 28, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.H.; Wu, T.H.; Guo, Y.H.; Li, T.L.; Chan, Y.L.; Wu, C.J. The concurrent treatment of Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi enhances the therapeutic efficacy of cisplatin but also attenuates chemotherapy-induced cachexia and acute kidney injury. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 243, 112075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R.; Li, L.; Gao, H.; Lou, K.; Luo, H.; Hao, S.; Yuan, J.; Liu, Z. Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and food effect of baicalein tablets in healthy Chinese subjects: A single-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, single-dose phase I study. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 274, 114052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.C.; Wu, Z.F.; Yin, Z.Q.; Lin, L.G.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Q.W. Coptidis rhizoma and its main bioactive components: Recent advances in chemical investigation, quality evaluation and pharmacological activity. Chin. Med. 2018, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, H.; Hu, B.; Yang, L.; Wang, P.; Wang, F.; Meng, X. Coptisine from Coptis chinensis inhibits production of inflammatory mediators in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated RAW 264.7 murine macrophage cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 780, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Wang, X.; Lin, S.; Dong, T.T.X.; Tsim, K.W.K. Berberine and palmatine, acting as allosteric potential ligands of α7 nAChR, synergistically regulate inflammation and phagocytosis of microglial cells. FASEB J. 2024, 38, e70094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, K.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.Y.; Li, B.; Zhu, W.L.; Shi, J.Y.; Jia, Q.; Li, Y.M. Advances in the study of berberine and its derivatives: A focus on anti-inflammatory and anti-tumor effects in the digestive system. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2017, 38, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xue, X.; Liu, J.; Li, Z.S.; Yang, G.Y.; Song, Y.; Pan, Y.; Ma, Y.; Hu, S.; et al. A Phase I Trial of Berberine in Chinese with Ulcerative Colitis. Cancer Prev. Res. 2020, 13, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.; May, B.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, A.L.; Lu, C.; Xue, C.C. A Pharmacological Review of Bioactive Constituents of Paeonia lactiflora Pallas and Paeonia veitchii Lynch. Phytother. Res. 2016, 30, 1445–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Li, F.; Zhang, X.; Li, P.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Z.; Li, D. In vitro synergistic antioxidant activity and identification of antioxidant components from Astragalus membranaceus and Paeonia lactiflora. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e96780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Lin, J.Z.; Li, L.; Yang, J.L.; Jia, W.W.; Huang, Y.H.; Du, F.F.; Wang, F.Q.; Li, M.J.; Li, Y.F.; et al. Pharmacokinetics and disposition of monoterpene glycosides derived from Paeonia lactiflora roots (Chishao) after intravenous dosing of antiseptic XueBiJing injection in human subjects and rats. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2016, 37, 530–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Li, C.; Gu, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, G.; Fan, M.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X. Paeoniflorin alleviated muscle atrophy in cancer cachexia through inhibiting TLR4/NF-κB signaling and activating AKT/mTOR signaling. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2024, 484, 116846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paik, S.; Song, G.Y.; Jo, E.K. Ginsenosides for therapeutically targeting inflammation through modulation of oxidative stress. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 121, 110461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, R.; Bryant, D.L.; Farone, A.L. Panax quinquefolius (North American Ginseng) Polysaccharides as Immunomodulators: Current Research Status and Future Directions. Molecules 2020, 25, 5854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Dai, X.; Zhu, R.; Chen, B.; Xia, B.; Ye, Z.; Zhao, D.; Gao, S.; Orekhov, A.N.; et al. A comprehensive review on the phytochemistry, pharmacokinetics, and antidiabetic effect of Ginseng. Phytomedicine 2021, 92, 153717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, L.C.; Bergfeld, W.F.; Belsito, D.V.; Hill, R.A.; Klaassen, C.D.; Liebler, D.C.; Marks, J.G., Jr.; Shank, R.C.; Slaga, T.J.; Snyder, P.W.; et al. Safety Assessment of Panax spp. Root-Derived Ingredients as Used in Cosmetics. Int. J. Toxicol. 2015, 34, 5s–42s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, P.T.; Rini, I.A.; Hoang, P.T.; Lee, T.K.; Lee, S. Exploring the potential of ginseng-derived compounds in treating cancer cachexia. J. Ginseng Res. 2025, 49, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.M.; Liang, Y.Q.; Tang, L.J.; Ding, Y.; Wang, X.H. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of Astragalus polysaccharide on EA.hy926 cells. Exp. Ther. Med. 2013, 6, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Shang, Q. Mechanistic insights into the antitumor effects of astragaloside IV and astragalus polysaccharide in digestive system cancers. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1691011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Li, S.; Du, Y.; Qin, X. Screening and structure study of active components of Astragalus polysaccharide for injection based on different molecular weights. J. Chromatogr. B 2020, 1152, 122255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Z.; Wei, L.; Zhang, C.; Yan, X. Astragalus polysaccharide, a component of traditional Chinese medicine, inhibits muscle cell atrophy (cachexia) in an in vivo and in vitro rat model of chronic renal failure by activating the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Exp. Ther. Med. 2017, 14, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jaeger, C.; Kruiskamp, S.; Voronska, E.; Lamberti, C.; Baramki, H.; Beaudeux, J.L.; Cherin, P. A Natural Astragalus-Based Nutritional Supplement Lengthens Telomeres in a Middle-Aged Population: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Zhang, K.; Wang, Y.; Ye, M.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, W.; Chen, L.; Li, H. The Rhizome of Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz.: A Comprehensive Review on the Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry and Pharmacology. Chem. Biodivers. 2025, 22, e202401879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, N.R.; Choi, W.G.; Zhu, A.; Park, J.; Kim, Y.T.; Hong, J.; Kim, B.J. Exploring the Therapeutic Effects of Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz against Human Gastric Cancer. Nutrients 2024, 16, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.L.; Li, N.; Shen, Q.; Fan, M.; Guo, X.D.; Zhang, X.W.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, X. Establishment of a mouse model of cancer cachexia with spleen deficiency syndrome and the effects of atractylenolide I. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2020, 41, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Yu, H.; Hou, A.; Man, W.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Zheng, S.; Jiang, H.; Kuang, H. A Review of the Ethnopharmacology, Phytochemistry, Pharmacology, Application, Quality Control, Processing, Toxicology, and Pharmacokinetics of the Dried Rhizome of Atractylodes macrocephala. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 727154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, X.; Fu, J.; Yin, X.; Cao, S.; Li, X.; Lin, L.; Ni, J. Emodin: A Review of its Pharmacology, Toxicity and Pharmacokinetics. Phytother. Res. 2016, 30, 1207–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, S.; Pradhan, B.; Nayak, R.; Behera, C.; Rout, L.; Jena, M.; Efferth, T.; Bhutia, S.K. Chemotherapeutic efficacy of curcumin and resveratrol against cancer: Chemoprevention, chemoprotection, drug synergism and clinical pharmacokinetics. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2021, 73, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattox, T.W. Cancer Cachexia: Cause, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2017, 32, 599–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Duan, C.; Liu, Y.; Lu, G.; Lyu, Q.; Liu, X.; Zheng, J.; Zhao, X.; Wang, S.; Zhao, H. Modulating effects of Astragalus polysaccharide on immune disorders via gut microbiota and the TLR4/NF-κB pathway in rats with syndrome of dampness stagnancy due to spleen deficiency. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2023, 24, 650–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Kim, H.I.; Park, J. The Role of Natural Products in the Improvement of Cancer-Associated Cachexia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Bai, L.; Wei, F.; Zhao, J.; Wang, D.; Xiao, Y.; Yan, W.; Wei, J. Therapeutic Mechanisms of Herbal Medicines Against Insulin Resistance: A Review. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hariono, M.; Julianus, J.; Djunarko, I.; Hidayat, I.; Adelya, L.; Indayani, F.; Auw, Z.; Namba, G.; Hariyono, P. The Future of Carica papaya Leaf Extract as an Herbal Medicine Product. Molecules 2021, 26, 6922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Herb | Experimental Model | Experimental Dose | Sample Size | Biomarker Alterations | Body Weight and Muscle Changes | Compliment | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coix lacryma-jobi L. var. ma-yuen (Roman.) Stapf | Mouse Lewis cachexia Model | Coicis Semen extract (Coicis Semen oil) 2.5 mL/kg/d gavage | n = 7 | Reduced MuRF-1 expression; reduced activation of NF-κB signaling pathway | The body weight of mice in the model group was 16 g, while that of mice in the Coicis Semen (coix seed) intervention group increased by 2 g. The cross-sectional area of muscle fibers improved from 700 μm2 to 800 μm2, with an increase of 100 μm2 (p < 0.05). | Only one dose group was set up, and negative results were not mentioned. | [136] |

| Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi | Mouse CT26 cachexia model | It was divided into two dose groups, at 150 mg/kg/d and 50 mg/kg/d respectively, while the control group was injected with 200 μL PBS. Drug administration was conducted continuously for 15 days. | n = 12 | Reduce Atrogin1, MuRF-1, IL-6, TNF-α expression; reduce activation of NF-κB signaling pathway | The three-day food intake of mice in the model group was 20 g; the food intake of the 150 mg/kg group increased by 12 g, and that of the 50 mg/kg group increased by 10 g. The body weight of the model group on Day 16 was 17 g, while the body weight of the two drug-treated groups increased by 3 g (p < 0.05). The muscle weight increased from 178 mg to 232 mg and 228 mg (p < 0.05). | Negative results were not mentioned. | [137] |

| Coptis chinensis Franch. | Mouse CT26 cachexia model | Coptis chinensis and berberine were mixed into the feed, with the set drug doses of 10 mg/g/d, 20 mg/g/d (for Coptis chinensis) and 1 mg/g/d, 4 mg/g/d (for berberine) respectively. Continuous observation was conducted for 14 days. | n = 6 | Improvement of feeding, reduction of body weight loss, reduction of IL-1, IL-6 | The weight of the gastrocnemius muscle improved from 95 g in the model group to 113 g, 144 g, and 133 g respectively (in the drug-treated groups). In terms of body weight, the model group showed a 5 g decrease from the initial 23 g; in contrast, the drug-treated groups only decreased by 2 g, dropping from 23 g to 21 g. | Negative results were not mentioned. | [138] |

| Paeonia lactiflora Pall. | Mouse CT26 cachexia model | Paeonia lactiflora extract, 50 mg/kg/d | n = 8 | Improve diet, reduce Atrogin1, MuRF-1, IL-6, TNF-α expression; reduce activation of NF-κB signaling pathway | The body weight of the model group was 23 g; compared with the model group, the body weight of the drug-treated group increased by 1 g. | Only one dose group was set up, and negative results were not mentioned. | [139] |

| Panax ginseng C. A. Mey. | Cisplatin-induced cachexia model in rats | Ginseng extract 25 mg and 50 mg/kg/d | n = 17 | Improvement of feeding and malaise, reduction of muscle loss | By day 35 of ginseng administration, body weight had increased by 30 g. | Negative results were not mentioned. | [140] |

| Astragalus membranaceus (Fisch.) Bunge | Lewis cachexia model in mice | 1 mg, 2.5 mg, 5 mg/kg/d Astragalus and Angelica sinensis | n = 10 | Inhibit serum levels of IL-6, IL-4, IL-1, and TNF-α, reduce phosphorylation of MAPK, NF-κB signaling pathway | The muscle cross-sectional diameter increased by 5 μm. The dietary intake was increased (1 mg group: 32.2 g/d, 2.5 mg group: 28.1 g/d, 5 mg group: 32.7 g/d, p < 0.015). | Negative results were not mentioned. | [141] |

| Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. | Mouse CT26 cachexia model | 25 mg/kg/d Atractylenolide | n = 7 | Reduced weight loss, decreased expression levels of IL-6, MuRF-1 and elevated MyoD expression levels | After 18 days of drug administration, the body weight of the model group was 22 g, while that of the drug-treated group was 24 g, which was an increase of 2 g compared with the model group. The muscle cross-sectional area increased from 120 μm2 to 180 μm2. | Only one dose group was set up, and negative results were not mentioned. | [142] |

| Polygonum cuspidatum Sieb. et Zucc. | Mouse A549 cachexia model | Mice were provided with feed containing 2% emodin ad libitum. | n = 5 | Inhibition of PTHLH and PTHrP expression, along with reduction of Atrogin1 and MuRF-1 expression. | The muscle weight in the model group was 725 mg, while in the emodin-treated group it was 800 mg, representing an increase of 75 mg. | Negative results were not mentioned. | [143] |

| Arctium lappa* L. | Mouse mild and severe CT26 cachexia model | Arctii Fructus 100 mg/d | n = 10 | Reduces IL-6 levels and decreases the expression of Atrogin1 and MuRF-1. | The model group had a body weight of 23 g, which was only 12%, 12.61%, and 14.23% lower than that of the treatment groups, respectively. | Negative results were not mentioned. | [144] |

| Magnolia officinalis Rehd. et Wils. | Cisplatin-induced cachexia model in mice | Combination of 50, 100 and 200 mg of Magnolia officinalis Rehd. et Wils. extract cisplatin injection | n = 10 | Upregulated the levels of macrophage M2 markers (CD206, Arg-1, TGF-β, and CD163) and increased the level of IGF-1. | The hindlimb weight in the control group was 0.8 g, and the treatment groups showed increases of 0.1 g, 0.2 g, and 0.3 g, respectively. | Negative results were not mentioned. | [145] |

| Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels | Lewis cachexia model in mice | 1 mg, 2.5 mg, 5 mg/kg/d Astragalus and Angelica sinensis | n = 10 | Inhibit serum levels of IL-6, IL-4, IL-1, and TNF-α, reduce phosphorylation of MAPK, NF-κB signaling pathway | Muscle cross-sectional diameter increased by 5 μm. Food intake was increased (1 mg group: 32.2 g/d; 2.5 mg group: 28.1 g/d; 5 mg group: 32.7 g/d; p < 0.015). | Negative results were not mentioned. | [141] |

| Comparison Dimension | Conventional Treatment of Cancer Cachexia | Natural Herbal Medicines |

|---|---|---|

| Regulation Mode | Single-point intervention, targeting only one pathological link of cachexia (e.g., central appetite, inflammation, nutritional supplementation), failing to cover the multi-organ interaction network | Systematic regulation, covering a large area at the same time, including intestinal barrier reconstruction, systemic inflammation inhibition, increase in muscle protein synthesis, appetite control, and so on, covering all key nodes of the “gut-immune-metabolism-muscle” axis |

| Therapeutic Target Spectrum | Single target (e.g., celecoxib only acts on COX-2; anti-IL-6 antibodies only bind to IL-6 receptors), making it difficult to address cross-disorder of multiple pathways | High safety, low incidence of adverse reactions, which are mostly mild and mainly gastrointestinal symptoms, can be relieved by reducing the dose or discontinuing the drug; most of the herbal medicines are of medicine-food homology and can be used for long-term intervention of cachexia patients |

| Safety | High incidence of adverse reactions, most of which are severe (e.g., thromboembolic risk of megestrol acetate, gastrointestinal injury from celecoxib), limiting long-term use | High safety and low frequency of adverse reactions that are mild (mainly gastrointestinal discomfort), can be relieved by reducing the dose or discontinuing the drug; most herbal medicines are of medicine-food homology, suitable for long-term intervention on cachexia patients |

| Modulatory Effect on the Core Pathological Cycle | Unable to break the core cycle of “inflammation—metabolic disorder—tissue depletion” (e.g., although celecoxib can inhibit inflammation, it cannot repair the intestinal barrier, making it difficult to prevent recurrent inflammation caused by continuous LPS entry into the bloodstream) | Can block important links of the core cycle through synergistic effects on different targets such as Astragalus membranaceus decreases LPS translocation by adjusting the intestinal flora (cut off inflammation source), inhibit NF-κB inflammatory pathway (stop inflammation in the middle), and activate the mTOR anabolic pathway (protect muscle downstream), break the vicious cycle on different levels |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Han, P.; Zhou, X.; Dong, G.; Ma, L.; Han, X.; Liu, D.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, J. Systematic Exploration of Molecular Mechanisms and Natural Herbal Therapeutic Strategies for Cancer Cachexia. Cancers 2026, 18, 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010104

Han P, Zhou X, Dong G, Ma L, Han X, Liu D, Zheng J, Zhang J. Systematic Exploration of Molecular Mechanisms and Natural Herbal Therapeutic Strategies for Cancer Cachexia. Cancers. 2026; 18(1):104. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010104

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Pengyu, Xingyu Zhou, Guomin Dong, Litian Ma, Xiao Han, Donghu Liu, Jin Zheng, and Jin Zhang. 2026. "Systematic Exploration of Molecular Mechanisms and Natural Herbal Therapeutic Strategies for Cancer Cachexia" Cancers 18, no. 1: 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010104

APA StyleHan, P., Zhou, X., Dong, G., Ma, L., Han, X., Liu, D., Zheng, J., & Zhang, J. (2026). Systematic Exploration of Molecular Mechanisms and Natural Herbal Therapeutic Strategies for Cancer Cachexia. Cancers, 18(1), 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010104