Unmet Needs and Their Impact on Quality of Life and Symptoms in Myelodysplastic Neoplasm Patients and Caregivers

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. QOL-E

- Physical well-being (QOL-FIS): four items (Items 3a–d).

- Functional well-being (QOL-FUN): three items (Items 4a–b and Item 5).

- Social and family life (QOL-SOC): four items (Items 6a–c and Item 7).

- Sexual well-being (QOL-SEX): two items (Item 8 and Item 14f).

- Fatigue (QOL-FAT): seven items (Item 9, Item 10, Items 11a–d, and Item 12).

- MDS-specific disturbances (QOL-SPEC): seven items (Item 13, Items 14a–e, and Item 14g).

- General (QOL-GEN): the average of all domains, except for QOL-SPEC.

- General (QOL-GENV): the average of all domains, except for QOL-SPEC and QOL-SEX.

- QOL-ALL: the average of QOL-GEN and QOL-SPEC.

- QOL-ALLV: the average of QOL-GEN and QOL-SPEC, except for QOL-SEX

- Treatment Outcome Index (QOL-TOI): the average of QOL-FIS, QOL-FUN, and QOL-SPEC.

2.3. HM-PRO

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. PROM QOL-E and HM-PRO

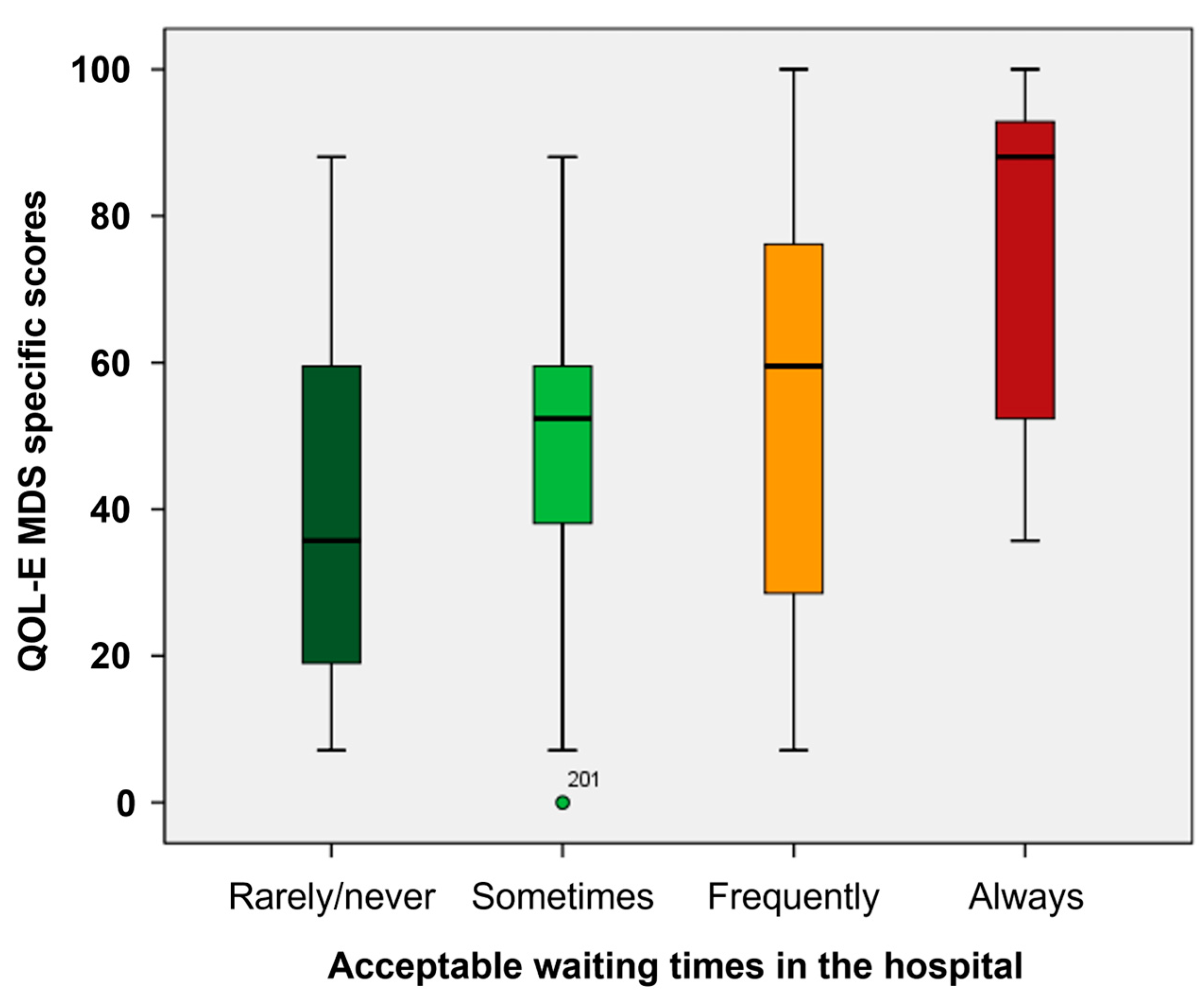

3.3. Impact of Distance from Hospital and Time Spent in Hospital on HRQoL

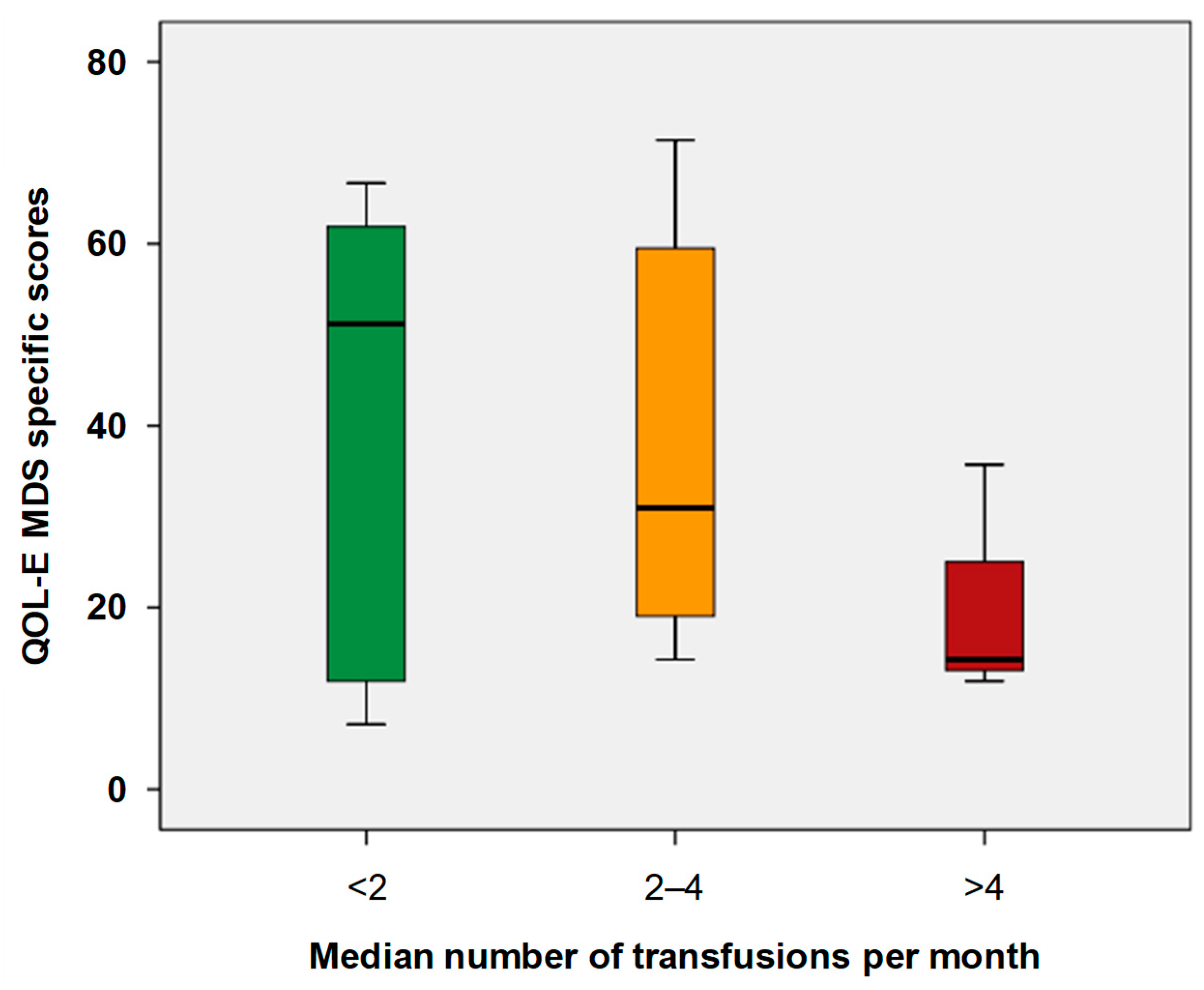

3.4. Impact of Treatment and Transfusion on HRQoL

3.5. Work Life

3.6. Patients’ Preferences and Communication with Physician

3.7. Caregivers

4. Discussion

5. Study Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIPaSiM | Associazione italiana pazienti sindromi mielodisplastica |

| alloHSCT | allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation |

| HM-PRO | hematological malignancy-patient-reported outcomes |

| HRQoL | health-related quality of life |

| HSTC | hematopoietic stem cell transplantation |

| IPSS-R | Revised International Prognostic Scoring System |

| IQR | interquartile range |

| MDS | myelodysplastic neoplasms |

| MDSS | MDS-specific |

| PRO | patient-reported outcome |

| PROM | PRO measure |

| QOL-E | HRQoL instrument developed specifically for MDS patients |

References

- Gorodokin, G.I.; Novik, A.A. Quality of Cancer Care. Ann. Oncol. 2005, 16, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowling, A. Health Care Rationing: The Public’s Debate. BMJ 1996, 312, 670–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arber, D.A.; Orazi, A.; Hasserjian, R.P.; Borowitz, M.J.; Calvo, K.R.; Kvasnicka, H.-M.; Wang, S.A.; Bagg, A.; Barbui, T.; Branford, S.; et al. International Consensus Classification of Myeloid Neoplasms and Acute Leukemias: Integrating Morphologic, Clinical, and Genomic Data. Blood 2022, 140, 1200–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekeres, M.A. Epidemiology, Natural History, and Practice Patterns of Patients with Myelodysplastic Syndromes in 2010. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2011, 9, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, P.L.; Tuechler, H.; Schanz, J.; Sanz, G.; Garcia-Manero, G.; Solé, F.; Bennett, J.M.; Bowen, D.; Fenaux, P.; Dreyfus, F.; et al. Revised International Prognostic Scoring System for Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Blood 2012, 120, 2454–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewersdorf, J.P.; Carraway, H.; Prebet, T. Emerging Treatment Options for Patients with High-Risk Myelodysplastic Syndrome. Ther. Adv. Hematol. 2020, 11, 2040620720955006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karel, D.; Valburg, C.; Woddor, N.; Nava, V.E.; Aggarwal, A. Myelodysplastic Neoplasms (MDS): The Current and Future Treatment Landscape. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 31, 1971–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Witte, T.; Bowen, D.; Robin, M.; Malcovati, L.; Niederwieser, D.; Yakoub-Agha, I.; Mufti, G.J.; Fenaux, P.; Sanz, G.; Martino, R.; et al. Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation for MDS and CMML: Recommendations from an International Expert Panel. Blood 2017, 129, 1753–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, E.N.; Platzbecker, U.; Fenaux, P.; Garcia-Manero, G.; LeBlanc, T.W.; Patel, B.J.; Kubasch, A.S.; Sekeres, M.A. Targeting Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Myelodysplastic Syndromes—Current Knowledge and Lessons to Be Learned. Blood Rev. 2021, 50, 100851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, E.N.; Finelli, C.; Santini, V.; Poloni, A.; Liso, V.; Cilloni, D.; Impera, S.; Terenzi, A.; Levis, A.; Cortelezzi, A.; et al. Quality of Life and Physicians’ Perception in Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Am. J. Blood Res. 2012, 2, 136–147. [Google Scholar]

- Stojkov, I.; Conrads-Frank, A.; Rochau, U.; Arvandi, M.; Koinig, K.A.; Schomaker, M.; Mittelman, M.; Fenaux, P.; Bowen, D.; Sanz, G.F.; et al. Determinants of Low Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Myelodysplastic Syndromes: EUMDS Registry Study. Blood Adv. 2023, 7, 2772–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stauder, R.; Yu, G.; Koinig, K.A.; Bagguley, T.; Fenaux, P.; Symeonidis, A.; Sanz, G.; Cermak, J.; Mittelman, M.; Hellström-Lindberg, E.; et al. Health-Related Quality of Life in Lower-Risk MDS Patients Compared with Age- and Sex-Matched Reference Populations: A European LeukemiaNet Study. Leukemia 2018, 32, 1380–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platzbecker, U.; Kubasch, A.S.; Homer-Bouthiette, C.; Prebet, T. Current Challenges and Unmet Medical Needs in Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Leukemia 2021, 35, 2182–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakar, S.; Gabarin, N.; Gupta, A.; Radford, M.; Warkentin, T.E.; Arnold, D.M. Anemia-Induced Bleeding in Patients with Platelet Disorders. Transfus. Med. Rev. 2021, 35, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caocci, G.; Baccoli, R.; Ledda, A.; Littera, R.; La Nasa, G. A Mathematical Model for the Evaluation of Amplitude of Hemoglobin Fluctuations in Elderly Anemic Patients Affected by Myelodysplastic Syndromes: Correlation with Quality of Life and Fatigue. Leuk. Res. 2007, 31, 249–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcovati, L.; Della Porta, M.G.; Strupp, C.; Ambaglio, I.; Kuendgen, A.; Nachtkamp, K.; Travaglino, E.; Invernizzi, R.; Pascutto, C.; Lazzarino, M.; et al. Impact of the Degree of Anemia on the Outcome of Patients with Myelodysplastic Syndrome and Its Integration into the WHO Classification-Based Prognostic Scoring System (WPSS). Haematologica 2011, 96, 1433–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efficace, F.; Gaidano, G.; Breccia, M.; Criscuolo, M.; Cottone, F.; Caocci, G.; Bowen, D.; Lübbert, M.; Angelucci, E.; Stauder, R.; et al. Prevalence, Severity and Correlates of Fatigue in Newly Diagnosed Patients with Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Br. J. Haematol. 2015, 168, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niscola, P.; Gianfelici, V.; Giovannini, M.; Piccioni, D.; Mazzone, C.; de Fabritiis, P. Quality of Life Considerations in Myelodysplastic Syndrome: Not Only Fatigue. Expert. Rev. Hematol. 2024, 17, 407–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Xu, X.; Ding, K.; Fu, R. Quality of Life Considerations and Management in Patients with Myelodysplastic Syndrome. Expert. Rev. Hematol. 2023, 16, 849–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, G.A.; Hebert, D.; Lee, C.; Rollison, D.; Gillis, N.; Komrokji, R.; Foran, J.M.; Liu, J.J.; Al Baghdadi, T.; Deeg, J.; et al. Health-Related Quality of Life and Vulnerability among People with Myelodysplastic Syndromes: A US National Study. Blood Adv. 2023, 7, 3506–3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.L. The Impact of Myelodysplastic Syndromes on Quality of Life: Lessons Learned from 70 Voices. J. Support. Oncol. 2012, 10, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K.; Williamson, M.; Brown, E.; Trenholm, E.; Hogea, C. Real-World Study of the Burden of Myelodysplastic Syndromes in Patients and Their Caregivers in Europe and the United States. Oncol. Ther. 2024, 12, 753–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, E.; Nobile, F.; Dimitrov, B. Development and Validation of QOL-E© Instrument for the Assessment of Health-Related Quality of Life in Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Cent. Eur. J. Med. 2013, 8, 835–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, P.; Oliva, E.N.; Ionova, T.; Else, R.; Kell, J.; Fielding, A.K.; Jennings, D.M.; Karakantza, M.; Al-Ismail, S.; Collins, G.P.; et al. Hematological Malignancy Specific Patient-Reported Outcome Measure (HM-PRO): Construct Validity Study. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goswami, P.; Oliva, E.N.; Ionova, T.; Else, R.; Kell, J.; Fielding, A.K.; Jennings, D.M.; Karakantza, M.; Al-Ismail, S.; Lyness, J.; et al. Paper and Electronic Versions of HM-PRO, a Novel Patient-Reported Outcome Measure for Hematology: An Equivalence Study. J. Comp. Eff. Res. 2019, 8, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, P.; Oliva, E.N.; Ionova, T.; Salek, S. Responsiveness and the Minimal Clinically Important Difference for HM-PRO in Patients with Hematological Malignancies. Blood 2018, 132, 2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, P.; Oliva, E.N.; Ionova, T.; Else, R.; Kell, J.; Fielding, A.K.; Jennings, D.M.; Karakantza, M.; Al-Ismail, S.; Collins, G.P.; et al. Development of a Novel Hematological Malignancy Specific Patient-Reported Outcome Measure (HM-PRO): Content Validity. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brownstein, C.G.; Daguenet, E.; Guyotat, D.; Millet, G.Y. Chronic Fatigue in Myelodysplastic Syndromes: Looking beyond Anemia. Crit. Rev. Oncol./Hematol. 2020, 154, 103067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalante, C.P.; Chisolm, S.; Song, J.; Richardson, M.; Salkeld, E.; Aoki, E.; Garcia-Manero, G. Fatigue, Symptom Burden, and Health-related Quality of Life in Patients with Myelodysplastic Syndrome, Aplastic Anemia, and Paroxysmal Nocturnal Hemoglobinuria. Cancer Med. 2019, 8, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andritsos, L.A.; McBride, A.; Tang, D.; Barghout, V.; Zanardo, E.; Song, R.; Huynh, L.; Yenikomshian, M.; Makinde, A.Y.; Hughes, C.; et al. Real-World Impact of Luspatercept on Red Blood Cell Transfusions among Patients with Myelodysplastic Syndromes: A United States Healthcare Claims Database Study. Leuk. Res. 2025, 148, 107624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenaux, P.; Platzbecker, U.; Mufti, G.J.; Garcia-Manero, G.; Buckstein, R.; Santini, V.; Díez-Campelo, M.; Finelli, C.; Cazzola, M.; Ilhan, O.; et al. Luspatercept in Patients with Lower-Risk Myelodysplastic Syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, E.N.; Platzbecker, U.; Garcia-Manero, G.; Mufti, G.J.; Santini, V.; Sekeres, M.A.; Komrokji, R.S.; Shetty, J.K.; Tang, D.; Guo, S.; et al. Health-Related Quality of Life Outcomes in Patients with Myelodysplastic Syndromes with Ring Sideroblasts Treated with Luspatercept in the MEDALIST Phase 3 Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 11, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, P.; Olshan, A.; Iraca, T.; Anthony, C.; Wintrich, S.; Sasse, E. Experiences and Support Needs of Caregivers of Patients with Higher-Risk Myelodysplastic Syndrome via Online Bulletin Board in the USA, Canada and UK. Oncol. Ther. 2024, 12, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soper, J.; Sadek, I.; Urniasz-Lippel, A.; Norton, D.; Ness, M.; Mesa, R. Patient and Caregiver Insights into the Disease Burden of Myelodysplastic Syndrome. Patient Relat. Outcome Meas. 2022, 13, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natalie Oliva, E.; Santini, V.; Antonella, P.; Liso, V.; Cilloni, D.; Terenzi, A.; Guglielmo, P.; Ghio, R.; Cortelezzi, A.; Semenzato, G.; et al. Quality of Life in Myelodysplastic Syndromes and Physicians’ Perception. Blood 2009, 114, 3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucioni, C.; Finelli, C.; Mazzi, S.; Oliva, E.N. Costs and Quality of Life in Patients with Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Am. J. Blood Res. 2013, 3, 246–259. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Santini, V.; Sanna, A.; Bosi, A.; Alimena, G.; Loglisci, G.; Levis, A.; Salvi, F.; Finelli, C.; Clissa, C.; Specchia, G.; et al. An Observational Multicenter Study to Assess the Cost of Illness and Quality of Life in Patients with Myelodysplastic Syndromes in Italy. Blood 2011, 118, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LoCastro, M.; Mortaz-Hedjri, S.; Wang, Y.; Mendler, J.H.; Norton, S.; Bernacki, R.; Carroll, T.; Klepin, H.; Liesveld, J.; Huselton, E.; et al. Telehealth Serious Illness Care Program for Older Adults with Hematologic Malignancies: A Single-Arm Pilot Study. Blood Adv. 2023, 7, 7597–7607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merz, A.M.A.; Platzbecker, U. Treatment of Lower-Risk Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Haematologica 2025, 110, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platzbecker, U. New Approaches for Anemia in MDS. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020, 20, S59–S60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Patient Characteristics (N = 259) | Median (IQR) | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 73.0 (64–79) | |

| Sex | ||

| M | 114 (44.0) | |

| F | 145 (56.0) | |

| Time from diagnosis | ||

| <1 year | 45 (18.3) | |

| 1–2 years | 59 (24.0) | |

| 2–5 years | 73 (29.7) | |

| 5–10 years | 46 (18.7) | |

| >10 years | 23 (9.3) | |

| Missing | 13 | |

| Ongoing treatment | ||

| Erythropoietin | 68 (27.9) | |

| Azacytidine | 40 (16.4) | |

| Lenalidomide | 14 (5.7) | |

| Hydroxycarbamide | 6 (2.5) | |

| Luspatercept | 16 (6.6) | |

| Chemotherapy | 9 (3.7) | |

| HSCT | 5 (2.0) | |

| Eltrombopag | 1 (0.4) | |

| Danazol | 1 (0.4) | |

| Unknown | 11 (4.5) | |

| No treatment | 73 (29.9) | |

| Transfusion dependence | ||

| Yes | 97 (42.4) | |

| No | 132 (57.6) | |

| Missing | 30 | |

| Median number of RBC unit/month | ||

| <2 | 33 (33.0) | |

| 2–4 | 54 (54.0) | |

| >4 | 13 (13.0) |

| QOL-E Index | HM-PRO Scores | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Domain (N) | Median Score (IQR) | Domain (N) | Median Score (IQR) |

| Physical (188) | 62.5 (37.5–75.0) | Physical (211) | 35.7 (7.1–65.5) |

| Function (158) | 66.6 (22.2–100) | Emotional (209) | 40.9 (13.6–59.1) |

| Social (158) | 50.0 (25.0–100) | Social (211) | 50.0 (0–66.7) |

| Sexual (90) | 66.6 (41.6–100) | Eating and drinking habits (209) | 25.0 (0–50.0) |

| Fatigue (183) | 76.2 (54.5–90.5) | Part A (211) | 34.3 (13.7–59.7) |

| MDS-specific (131) | 59.5 (34.5–88.1) | Part B (196) | 17.6 (2.9–26.4) |

| General (62) | 58.2 (43.8–86.3) | ||

| Treatment outcome index (101) | 62.9 (34.5–83.5) | ||

| All (54) | 62.5 (36.7–86.1) | ||

| Percentiles | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | Median | 75 | p-Value | ||

| PB_SCORE | No | 0.0 | 21.4 | 50.0 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 35.7 | 53.6 | 71.4 | ||

| EB_SCORE | No | 9.1 | 31.8 | 45.5 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 30.7 | 56.8 | 67.0 | ||

| SW_SCORE | No | 0.0 | 50.0 | 66.7 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 33.3 | 66.7 | 83.3 | ||

| ED_SCORE | No | 0.0 | 25.0 | 25.0 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 0.0 | 25.0 | 50.0 | ||

| PARTA_SCORE | No | 6.3 | 26.6 | 52.3 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 31.8 | 56.0 | 68.8 | ||

| SS_SCORE | No | 0.0 | 8.8 | 20.6 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 12.5 | 20.6 | 31.6 | ||

| QOL-FIS | No | 50.0 | 62.5 | 87.5 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 37.5 | 50.0 | 71.9 | ||

| QOL-FUN | No | 22.2 | 88.9 | 100.0 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 22.2 | 22.2 | 63.9 | ||

| QOL-SOC | No | 37.5 | 75.0 | 100.0 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 15.6 | 25.0 | 71.9 | ||

| QOL-FAT | No | 66.7 | 81.0 | 90.5 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 57.1 | 64.3 | 76.2 | ||

| QOL-SPEC | No | 50.0 | 73.8 | 92.9 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 19.0 | 44.0 | 61.3 | ||

| QOL-GEN | No | 53.8 | 72.0 | 88.1 | 0.003 |

| Yes | 32.3 | 46.7 | 65.8 | ||

| QOL-GENV | No | 53.5 | 73.4 | 91.4 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 34.8 | 40.1 | 66.5 | ||

| QOL-ALL | No | 53.2 | 71.3 | 88.6 | 0.005 |

| Yes | 33.0 | 43.3 | 64.4 | ||

| QOL-ALLV | No | 52.4 | 77.3 | 90.5 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 33.0 | 42.2 | 64.7 | ||

| QOL-TOI | No | 55.2 | 69.8 | 87.7 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 30.4 | 38.3 | 65.2 | ||

| Percentiles | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | Median | 75 | p-Value | ||

| PB_SCORE | Yes | 32.1 | 57.1 | 78.6 | <0.001 |

| No | 0.0 | 21.4 | 37.9 | ||

| EB_SCORE | Yes | 45.5 | 56.8 | 69.3 | <0.001 |

| No | 9.1 | 22.7 | 43.2 | ||

| SW_SCORE | Yes | 33.3 | 66.7 | 100.0 | <0.001 |

| No | 0.0 | 0.0 | 66.7 | ||

| ED_SCORE | Yes | 18.8 | 50.0 | 62.5 | <0.001 |

| No | 0.0 | 0.0 | 25.0 | ||

| PARTA_SCORE | Yes | 35.3 | 59.8 | 70.7 | <0.001 |

| No | 4.3 | 23.7 | 39.8 | ||

| SS_SCORE | Yes | 14.0 | 19.1 | 30.1 | 0.044 |

| No | 0.0 | 11.8 | 20.6 | ||

| QOL-FIS | Yes | 37.5 | 50.0 | 62.5 | <0.001 |

| No | 43.8 | 62.5 | 93.8 | ||

| QOL-SOC | Yes | 25.0 | 25.0 | 50.0 | <0.001 |

| No | 43.8 | 87.5 | 100.0 | ||

| QOL-FAT | Yes | 56.0 | 64.3 | 77.4 | <0.001 |

| No | 66.7 | 81.0 | 90.5 | ||

| QOL-SPEC | Yes | 14.3 | 31.0 | 59.5 | <0.001 |

| No | 54.8 | 81.0 | 92.9 | ||

| QOL-GEN | Yes | 31.9 | 41.1 | 65.5 | <0.001 |

| No | 49.0 | 73.4 | 91.5 | ||

| QOL-ALL | Yes | 30.0 | 40.1 | 64.2 | <0.001 |

| No | 50.1 | 77.3 | 90.6 | ||

| QOL-TOI | Yes | 27.9 | 35.1 | 70.4 | <0.001 |

| No | 44.2 | 68.5 | 92.5 | ||

| Preferred Place for Transfusion | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Home | Hospital | p-Value | |

| HM-PRO scores; median (IQR) | |||

| Emotional | 59 (29–68) | 50 (25–50) | 0.045 |

| Part B | 31 (19–52) | 16 (7–27) | 0.008 |

| QOL-E scores; median (IQR) | |||

| Functional | 25 (11–44) | 37 (17–47) | 0.006 |

| Fatigue | 57 (26–39) | 64 (30–42) | 0.007 |

| MDS specific | 27 (10–30) | 32 (19–35) | 0.012 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Crisà, E.; Cilloni, D.; Riva, M.; Balleari, E.; Barraco, D.; Manghisi, B.; Borin, L.; Calmasini, M.; Calvisi, A.; Capodanno, I.; et al. Unmet Needs and Their Impact on Quality of Life and Symptoms in Myelodysplastic Neoplasm Patients and Caregivers. Cancers 2025, 17, 1587. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17091587

Crisà E, Cilloni D, Riva M, Balleari E, Barraco D, Manghisi B, Borin L, Calmasini M, Calvisi A, Capodanno I, et al. Unmet Needs and Their Impact on Quality of Life and Symptoms in Myelodysplastic Neoplasm Patients and Caregivers. Cancers. 2025; 17(9):1587. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17091587

Chicago/Turabian StyleCrisà, Elena, Daniela Cilloni, Marta Riva, Enrico Balleari, Daniela Barraco, Beatrice Manghisi, Lorenza Borin, Michela Calmasini, Anna Calvisi, Isabella Capodanno, and et al. 2025. "Unmet Needs and Their Impact on Quality of Life and Symptoms in Myelodysplastic Neoplasm Patients and Caregivers" Cancers 17, no. 9: 1587. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17091587

APA StyleCrisà, E., Cilloni, D., Riva, M., Balleari, E., Barraco, D., Manghisi, B., Borin, L., Calmasini, M., Calvisi, A., Capodanno, I., Della Porta, M. G., Diral, E., Fattizzo, B., Fenu, S., Paolini, S., Finelli, C., Fozza, C., Frairia, C., Giai, V., ... Oliva, E. N. (2025). Unmet Needs and Their Impact on Quality of Life and Symptoms in Myelodysplastic Neoplasm Patients and Caregivers. Cancers, 17(9), 1587. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17091587