An Interprofessional Approach to Developing Family Psychosocial Support Programs in a Pediatric Oncology Healthcare Setting

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Development of a Scope of Practice Document to Enhance Collaboration

2.2. Development of Caregiver Support Task Force

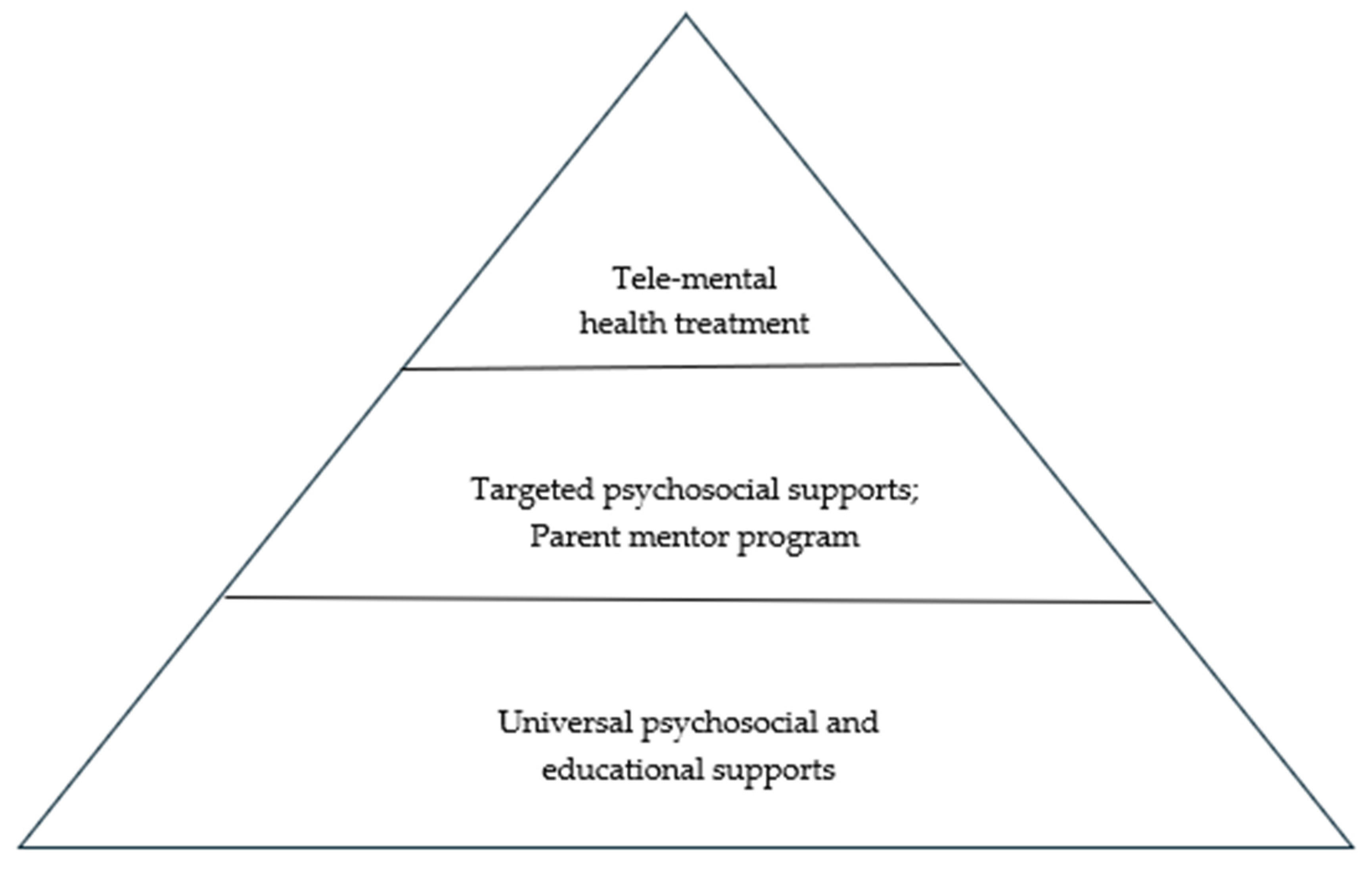

3. Results

3.1. Universal Tier Programs

3.2. Targeted Tier Programs

3.3. Clinical/Treatment Tier Programs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pai, A.L.H.; Greenley, R.N.; Lewandowski, A.; Drotar, D.; Youngstrom, E.; Peterson, C.C. A meta-analytic review of the influence of pediatric cancer on parent and family functioning. J. Fam. Psychol. 2007, 21, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrides, N.; Pao, M. Updates in paediatric psycho-oncology. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2014, 26, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Askins, M.A.; Moore, B.D. Psychosocial support of the pediatric cancer patient: Lessons learned over the past 50 years. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2008, 10, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neylon, K.; Condren, C.; Guerin, S.; Looney, K. What are the psychosocial needs of adolescents and young adults with cancer? A systematic review of the literature. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2023, 12, 799–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazak, A.E. Pediatric Psychosocial Preventative Health Model (PPPHM): Research, practice, and collaboration in pediatric family systems medicine. Fam. Syst. Health 2006, 24, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, L.; Kazak, A.E.; Noll, R.B.; Patenaude, A.D.; Kupst, M.J. Standards for the Psychosocial Care of Children with Cancer and Their Families: An introduction to the special issue. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2015, 62 (Suppl. 5), S419–S424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazak, A.E.; Scialla, M.; Deatrick, J.A.; Barakat, L.P. Pediatric Psychosocial Preventative Health Model: Achieving equitable psychosocial care for children and families. Fam. Syst. Health 2024, 42, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiener, L.; Canter, K.; Long, K.; Psihogios, A.M.; Thompson, A.L. Pediatric Psychosocial Standards of Care in action: Research that bridges the gap from need to implementation. Psychooncology 2020, 29, 2033–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiener, L.; Kazak, A.E.; Noll, R.B.; Patenaude, A.F.; Kupst, M.J. Interdisciplinary collaboration in standards of psychosocial care. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2015, 62 (Suppl. 5), S425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scialla, M.A.; Canter, K.S.; Chen, F.F.; Kolb, E.A.; Sandler, E.; Wiener, L.; Kazak, A.E. Implementing the psychosocial standards in pediatric cancer: Current staffing and services available. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2017, 64, e26634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, A.C.; Mullins, L.L.; Mullins, A.J.; Muriel, A.C. Psychosocial interventions and therapeutic support as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2015, 62 (Suppl. 5), S585–S618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, C.; Lennox, L.; Bell, D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e001570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschmann, H.E.; Boyd, C.M.; Robbins, C.W.; Chan, W.V.; Mularski, R.A.; Bennett, W.L.; Sheehan, O.C.; Wilson, R.F.; Bayliss, E.A.; Leff, B.; et al. Informing patient-centered care through stakeholder engagement and highly stratified quantitative benefit-harm assessments. Value Health 2020, 23, 616–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.H.; Abraham, M.R. Partnering with Patients, Residents, and Families—A Resource for Leaders of Hospitals, Ambulatory Care Settings, and Long-Term Care Communities; Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Prior, S.J.; Campbell, S. Patient and family involvement: A discussion of co-led redesign of healthcare services. J. Particip. Med. 2018, 10, e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurbergs, N.; Elliott, D.A.; Browne, E.; Sirrine, E.; Brasher, S.; Leigh, L.; Powell, B.; Crabtree, V.M. How I approach: Defining the scope of psychosocial care across disciplines in pediatric hematology-oncology. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2022, 69, e29809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, J.A.; Salley, C.G.; Muriel, A.C. Standards of psychosocial care for parents of children with cancer. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2015, 62 (Suppl. 5), S632–S683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.L.; Young-Saleme, T.K. Anticipatory guidance and psychoeducation as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2015, 62 (Suppl. 5), S684–S693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhardt, C.A.; Lehmann, V.; Long, K.A.; Alderfer, M.A. Supporting siblings as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2015, 62 (Suppl. 5), S750–S804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, D.A.; Corneua-Dia, D.E.; Turner, E.; Barnett, B.; Parris, K.R. Caregiver mental health in pediatric oncology: A three-tiered model of supports. Psycho-Oncology 2021, 30, 267–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Together by St. Jude™. Available online: https://together.stjude.org/en-us/ (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Caregivers SHARE. Available online: https://www.stjude.org/care-treatment/patient-families/family-caregiver/caregivers-share-podcast.html (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Harper, F.W.K.; Albrecht, T.L.; Trentacosta, C.J.; Taub, J.W.; Phipps, S.; Penner, L.A. Understanding differences in the long-term psychosocial adjustment of pediatric cancer patients and their parents: An individual differences resource model. Transl. Behav. Med. 2019, 9, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolgin, M.J.; Phipps, S.; Faircloug, D.L.; Sahler, O.J.Z.; Askins, M.; Noll, R.B.; Butler, R.; Varni, J.W.; Katz, E.R. Trajectories of adjustment in mothers of children with newly diagnosed cancer: A natural history investigation. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2007, 32, 771–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goertz, M.T.; Brosig, C.; Bice-Urbach, B.; Malkoff, A.; Kroll, K. Development of a telepsychology program for parents of pediatric patients. Clin. Pract. Pediatr. Psychol. 2021, 9, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, M.; Dimovski, A.; Muscara, F.; Yamada, J.; Burke, K.; McCarthy, M.; Hearps, S.J.C.; Anderson, V.A.; Coe, A.; Hayes, L.; et al. Participating from the comfort of your own home: Feasibility of a group videoconferencing intervention to reduce distress in parents of children with a serious illness or injury. Child. Fam. Behav. Ther. 2016, 38, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teleheatlh.HHS.gov: Licensing Across State Lines. Available online: https://telehealth.hhs.gov/licensure/licensing-across-state-lines (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Kokorelias, K.M.; Gignac, M.A.M.; Naglie, G.; Cameron, J.I. Towards a universal model of family centered care: A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Motlaq, M.A.; Carter, B.; Neill, S.; Hallstrom, I.K.; Foster, M.; Coyne, I.; Arabiat, D.; Darbyshire, P.; Feeg, V.D.; Shields, L. Toward developing consensus on family-centered care: An international descriptive study and discussion. J. Child Health Care 2019, 23, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giguère, A.; Zomahoun, H.T.V.; Carmichael, P.H.; Uwizeye, C.B.; Légaré, F.; Grimshaw, J.M.; Gagnon, M.P.; Auguste, D.U.; Massougbodji, J. Printed educational materials: Effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 8, CD004398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Child Life | Music Therapy | Psychology | Resilience Center | School Program | Social Work | Spiritual Care | |

| Universal Tier | |||||||

| Caregiver Connections | S | S | S | S | S | C/I | S |

| Sibling Connections | C/I | S | S | S | S | C/I | S |

| The Caregiver Project | C/I | C/I | S | S | S | S | S |

| Psychoeducational Workshops | C/I | C/I | C/I | C/I | C/I | C/I | C/I |

| Podcast | C/I | C/I | C/I | S | S | C/I | C/I |

| Paws at Play | C/I | C/I | C/I | C/I | C/I | C/I | C/I |

| Targeted Tier | |||||||

| Individual Interventions | C/I | C/I | C/I | C/I | C/I | C/I | C/I |

| The Mentor Program | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| Clinical Tier | |||||||

| Tele-Mental Health Program | S | S | C/I | S | S | C/I | S |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Turner, E.; Sirrine, E.H.; Crabtree, V.M.; Elliott, D.A.; Carr, A.; Elsener, P.; Parris, K.R. An Interprofessional Approach to Developing Family Psychosocial Support Programs in a Pediatric Oncology Healthcare Setting. Cancers 2025, 17, 1342. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17081342

Turner E, Sirrine EH, Crabtree VM, Elliott DA, Carr A, Elsener P, Parris KR. An Interprofessional Approach to Developing Family Psychosocial Support Programs in a Pediatric Oncology Healthcare Setting. Cancers. 2025; 17(8):1342. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17081342

Chicago/Turabian StyleTurner, Erin, Erica H. Sirrine, Valerie McLaughlin Crabtree, D. Andrew Elliott, Ashley Carr, Paula Elsener, and Kendra R. Parris. 2025. "An Interprofessional Approach to Developing Family Psychosocial Support Programs in a Pediatric Oncology Healthcare Setting" Cancers 17, no. 8: 1342. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17081342

APA StyleTurner, E., Sirrine, E. H., Crabtree, V. M., Elliott, D. A., Carr, A., Elsener, P., & Parris, K. R. (2025). An Interprofessional Approach to Developing Family Psychosocial Support Programs in a Pediatric Oncology Healthcare Setting. Cancers, 17(8), 1342. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17081342