Development of an Evaluation Tool for Monitoring the Delivery of Psychosocial Care in Pediatric Oncology Settings

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

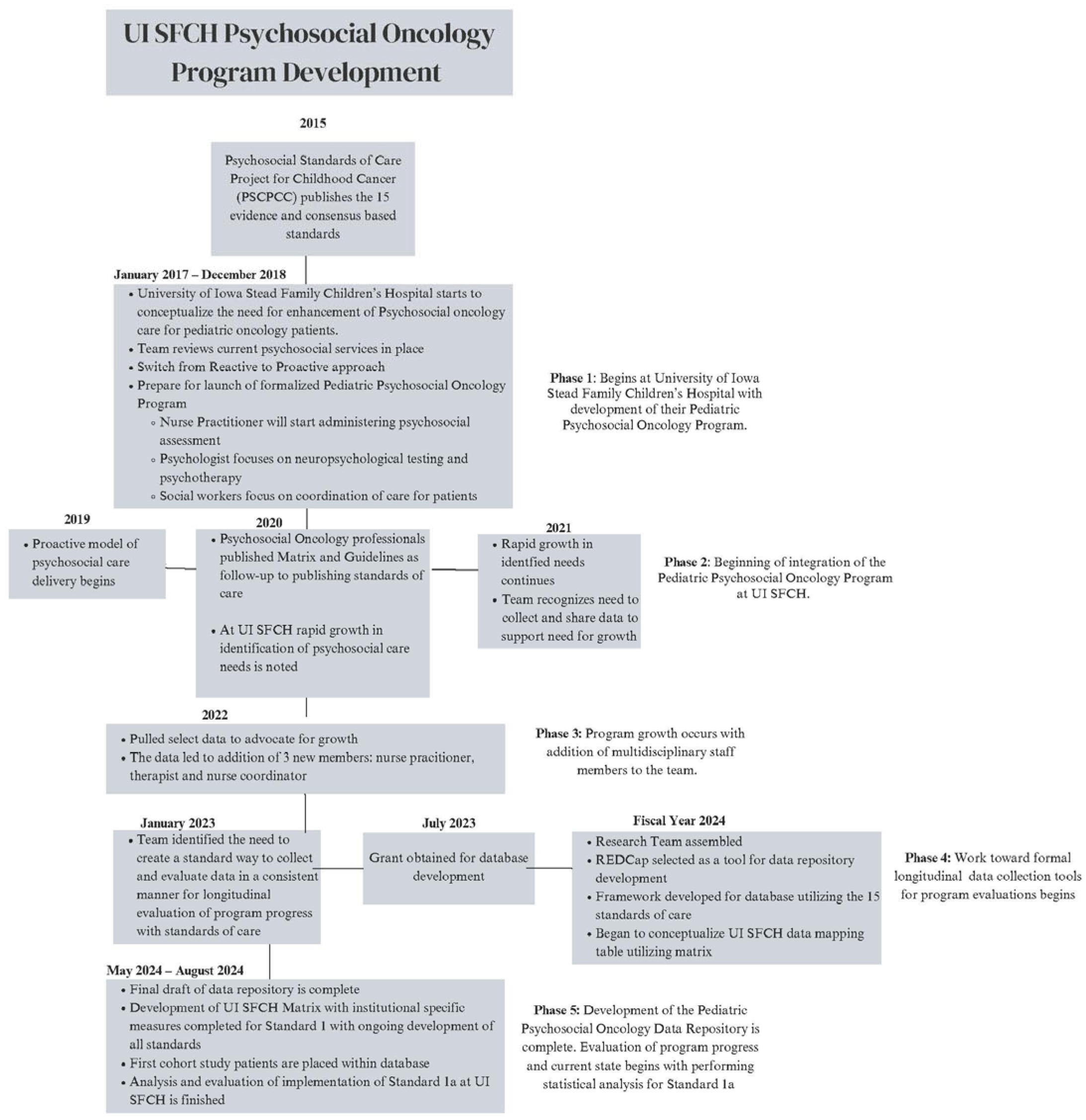

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Human Subject Protection

2.2. Procedures/Methods

2.2.1. Development of an Institution-Specific Matrix

2.2.2. Chart Review Development

2.2.3. REDCap® Database Collection

2.2.4. Data Collection and Creation of a Training Manual

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

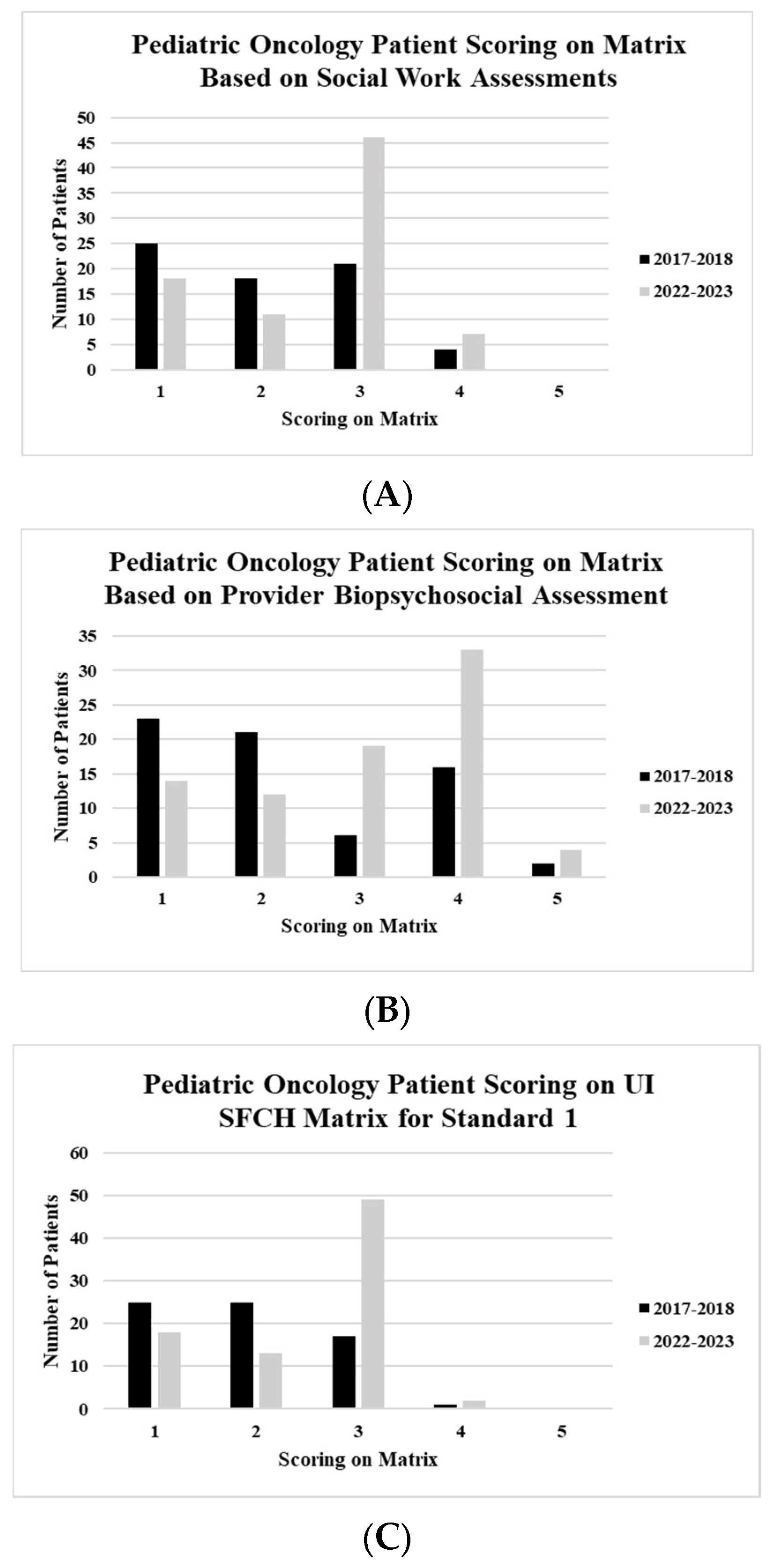

3.2. Standard 1.A. Matrix Scoring for Social Work Assessments

3.3. Standard 1.A. Matrix Scoring for Provider Biopsychosocial Assessments

3.4. Standard 1.A. Combined Matrix Scoring

4. Discussion

4.1. Receipt of Social Work Assessments

4.2. Receipt of Provider Biopsychosocial Assessments

4.3. Combined Matrix Scoring

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Osmani, V.; Hörner, L.; Klug, S.J.; Tanaka, L.F. Prevalence and risk of psychological distress, anxiety and depression in adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 18354–18367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Płotka, A.; Chęcińska, A.; Zając-Spychała, O.; Więckowska, B.; Kramer, L.; Szymańska, P.; Adamczewska-Wawrzynowicz, K.; Barełkowska, M.; Wachowiak, J.; Derwich, K. Psychosocial Late Effects in Adolescent and Young Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer Diagnosed with Leukemia, Lymphoma, and Central Nervous System Tumor. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2021, 10, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.R.Y.B.; Low, C.E.; Yau, C.E.; Li, J.; Ho, R.; Ho, C.S.H. Lifetime Burden of Psychological Symptoms, Disorders, and Suicide Due to Cancer in Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Years: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2023, 177, 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kirk, D.; Kabdebo, I.; Whitehead, L. Prevalence of distress, its associated factors and referral to support services in people with cancer. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021, 30, 2873–2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, B.M.; Zevon, M.A.; D’Arrigo, M.C.; Cecchini, T.B. Screening for distress in cancer patients: The NCCN rapid-screening measure. Psycho-Oncology 2004, 13, 792–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, P.B.; Wagner, L.I. A new quality standard: The integration of psychosocial care into routine cancer care. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 1154–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Distress Management: NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology; Version I; National Comprehensive Cancer Network: Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA, 2018.

- Zeltzer, L.K.; Recklitis, C.; Buchbinder, D.; Zebrack, B.; Casillas, J.; Tsao, J.C.; Lu, Q.; Krull, K. Psychological status in childhood cancer survivors: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 2396–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hinnen, C.; von Haeseler, E.; Tijssens, F.; Mols, F. Adverse childhood events and mental health problems in cancer survivors: A systematic review. Support. Care Cancer 2024, 32, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Patenaude, A.F.; Brown, P. Psychosocial interventions and therapeutic support as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2015, 62, S585–S618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, M.N.; Madden, R.E.; Zukin, H.N.; Velazquez-Martin, B.; Barakat, L.P. Psychosocial needs of pediatric cancer patients and their caregivers at end of treatment: Why psychosocial screening remains important. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2023, 70, e30540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiener, L.; Kazak, A.E.; Noll, R.B.; Patenaude, A.F.; Kupst, M.J. Standards for the Psychosocial Care of Children With Cancer and Their Families: An Introduction to the Special Issue. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2015, 62 (Suppl. 5), S419–S424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, B.L.; Currin-McCulloch, J.; Pelletier, W.; Sardi-Brown, V.; Brown, P.; Wiener, L. Psychosocial standards of care for children with cancer and their families: A national survey of pediatric oncology social workers. Soc. Work Health Care 2018, 57, 221–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scialla, M.A.; Canter, K.S.; Chen, F.F.; Kolb, E.A.; Sandler, E.; Wiener, L.; Kazak, A.E. Implementing the psychosocial standards in pediatric cancer: Current staffing and services available. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2017, 64, e26634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scialla, M.A.; Wiener, L.; Canter, K.S.; Brown, V.S.; Buff, K.; Arasteh, K.; Pariseau, E.; Sandler, E.; Kazak, A.E. Benchmarks for Psychosocial Staffing in Pediatric Oncology: Implementing the Standards Together-Engaging Parents and Providers in Psychosocial Care (iSTEPPP) Study. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2025, 72, e31676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deshields, T.; Kracen, A.; Nanna, S.; Kimbro, L. Psychosocial staffing at National Comprehensive Cancer Network member institutions: Data from leading cancer centers. Psychooncology 2016, 25, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kayser, K.; Brydon, D.M.; Moon, H.; Zebrack, B. Institutional capacity to provide psychosocial care in cancer programs: Addressing barriers to delivering quality cancer care. Psychooncology 2020, 29, 1995–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiener, L.; Canter, K.; Long, K.; Psihogios, A.M.; Thompson, A.L. Pediatric Psychosocial Standards of Care in action: Research that bridges the gap from need to implementation. Psycho-Oncology 2020, 29, 2033–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiener, L.; Kupst, M.J.; Pelletier, W.; Kazak, A.E.; Thompson, A.L. Tools to guide the identification and implementation of care consistent with the psychosocial Standards of care. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2020, 67, e28586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilleland Marchak, J.E.; Halpin, S.N.; Escoffery, C.; Owolabi, S.; Mertens, A.C.; Wasilewski-Masker, K. Using formative evaluation to plan for electronic psychosocial screening in pediatric oncology. Psycho-Oncology 2021, 30, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazak, A.E.; Brier, M.; Alderfer, M.A.; Reilly, A.; Fooks Parker, S.; Rogerwick, S.; Ditaranto, S.; Barakat, L.P. Screening for psychosocial risk in pediatric cancer. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2012, 59, 822–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Courtnage, T.; Bates, N.E.; Armstrong, A.A.; Seitz, M.K.; Weitzman, T.S.; Fann, J.R. Enhancing integrated psychosocial oncology through leveraging the oncology social worker’s role in collaborative care. Psycho-Oncology 2020, 29, 2084–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshalla, K.H.; Pincus, H.A.; Tesson, S.; Lingam, R.; Woolfenden, S.R.; Kasparian, N.A. Integrated Psychological Care in Pediatric Hospital Settings for Children with Complex Chronic Illness and Their Families: A Systematic Review. Psychol. Health 2022, 39, 452–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrera, M.; Hancock, K.; Atenafu, E.; Alexander, S.; Solomon, A.; Desjardins, L.; Shama, W.; Chung, J.; Mills, D.; the Psychosocial Standards of Care Project. Psychosocial screening and mental health in pediatric cancer: A randomized controlled trial. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 3659–3668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baum, K.T.A.; Powell, S.K.; Jacobson, L.A.; Gragert, M.N.; Janzen, L.A.; Paltin, I.; Rey-Casserly, C.M.; Wilkening, G.N. Implementing guidelines: Proposed definitions of neuropsychology services in pediatric oncology. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2017, 64, e26446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, K.K.S.; Abrahão, A.A. Research Development Using REDCap Software. Healthc. Inform. Res. 2021, 27, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, H.; Ivanova, J.; Wilczewski, H.; Ong, T.; Ross, J.N.; Bailey, A.; Cummins, M.; Barrera, J.; Bunnell, B.; Welch, B. User Preferences and Needs for Health Data Collection Using Research Electronic Data Capture: Survey Study. JMIR Med. Inform. 2024, 12, e49785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Saqlain, F.; Shalhout, S.Z.; Flaherty, K.T.; Emerick, K.S.; Miller, D.M. REDCap-Based Operational Tool to Guide Care Coordination in a Multidisciplinary Cutaneous Oncology Clinic. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2021, 17, e1189–e1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin, N.M.; Butow, P.N.; Hack, T.F.; Shaw, J.M.; Shepherd, H.L.; Ugalde, A.; Sales, A.E. An implementation science primer for psycho-oncology: Translating robust evidence into practice. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. Res. Pract. 2019, 1, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McTate, E.; Szulczewski, L.; Joffe, N.E.; Chan, S.F.; Pai, A.L. Implementation of the Psychosocial Standards for Caregiver Mental Health Within a Pediatric Hematology/Oncology Program. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2021, 28, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Standard 1. Youth with Cancer and Their Families Routinely Receive Systematic Assessments of Their Psychosocial Healthcare Needs. | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1: Consider that each of these have dimensions of the following: (a) periodicity (specified as at diagnosis, relapse/disease progression, and at end of treatment), (b) standardized process (systematic assessment), (c) content (see specified domains) | ||

1.A.: Assessment domains: Youth

| ||

| Level | Original Matrix Scoring | |

| 1 | No organized process in place for systematic assessments | |

| 2 | * To be defined at an institution specific level | |

| 3 | There is a system in place to assure that all youth receive assessment of psychosocial functioning early in the treatment trajectory and again only if clinically indicated | |

| 4 | * To be defined at an institution specific level | |

| 5 | All youth receives a comprehensive assessment at regularly scheduled points in their care | |

| Level | UIHC Modified Scoring | Chart Review Elements |

| 1 | No assessments completed on a child: Social Work Assessment (SWA) OR Provider Biopsychosocial Assessment (PBA) | Was a social work assessment completed? Y/N

Frequency of SW check in during therapy Frequency of SW check in post therapy Psychosocial work assessment completed? Y/N

Time between visits (e.g., time in between first assessment and second assessment) Completed Oncology Treatment? Y/N (Date of completion) Psychosocial oncology assessment at the end of treatment? Y/N (Date of assessment) |

| 2 | Assessments completed as follows: Initial SWA completed at any time following diagnosis AND No PBA completed | |

| 3 | Assessments completed as follows: Initial SWA completed at diagnosis (within 1 month) AND One PBA completed any time after diagnosis | |

| 4 | Assessments completed as follows: SWA completed at least once at diagnosis (within 1 month) AND at least one SWA completed within the first year following the end of treatment (12 ± 3 months) AND PBA initial assessment completed AND at least one additional follow-up PBA completed | |

| 5 | Assessments completed as follows: SWA completed at least once at diagnosis (within 1 month) AND Annually (12 ± 3 months) following the end of treatment and continuing for a lifetime AND PBA at the following time points: Initial (within 4 weeks of diagnosis), minimum of every 3 months throughout treatment, end of treatment (±2 months of treatment completion), and at least twice within the year following treatment completion (±3 months), and Annually (12 ± 3 months), continuing for a lifetime | |

| 2017–2018 Cohort | 2022–2023 Cohort | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| Age at Diagnosis | ||||

| <1 year old | 3 | 4 | 9 | 11 |

| 1–2 years old | 9 | 13 | 11 | 13 |

| 3–4 years old | 11 | 16 | 8 | 10 |

| 5–7 years old | 13 | 20 | 7 | 9 |

| 8–10 years old | 7 | 10 | 12 | 15 |

| 11–14 years old | 12 | 18 | 16 | 20 |

| 15–18 years old | 9 | 13 | 19 | 22 |

| 19–25 years old | 4 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Diagnosis Group | ||||

| Non-oncology transplant | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Leukemia/Lymphoma | 22 | 32 | 20 | 24 |

| Neuro-oncology | 14 | 21 | 34 | 41 |

| Solid tumor | 31 | 46 | 27 | 34 |

| Racial Identity | ||||

| White | 54 | 79 | 70 | 85 |

| Asian American | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| African American | 5 | 7 | 4 | 5 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 5 | 7 | 6 | 7 |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Multiracial | 4 | 6 | 2 | 3 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 24 | 35 | 41 | 50 |

| Male | 44 | 65 | 41 | 50 |

| Intersex | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Foster, K.; Sadler, B.; Conrad, A.L.; Grafft, A. Development of an Evaluation Tool for Monitoring the Delivery of Psychosocial Care in Pediatric Oncology Settings. Cancers 2025, 17, 1550. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17091550

Foster K, Sadler B, Conrad AL, Grafft A. Development of an Evaluation Tool for Monitoring the Delivery of Psychosocial Care in Pediatric Oncology Settings. Cancers. 2025; 17(9):1550. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17091550

Chicago/Turabian StyleFoster, Kristin, Bethany Sadler, Amy L. Conrad, and Amanda Grafft. 2025. "Development of an Evaluation Tool for Monitoring the Delivery of Psychosocial Care in Pediatric Oncology Settings" Cancers 17, no. 9: 1550. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17091550

APA StyleFoster, K., Sadler, B., Conrad, A. L., & Grafft, A. (2025). Development of an Evaluation Tool for Monitoring the Delivery of Psychosocial Care in Pediatric Oncology Settings. Cancers, 17(9), 1550. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17091550