Naso-Ethmoidal Schwannoma: From Pathology to Surgical Strategies

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

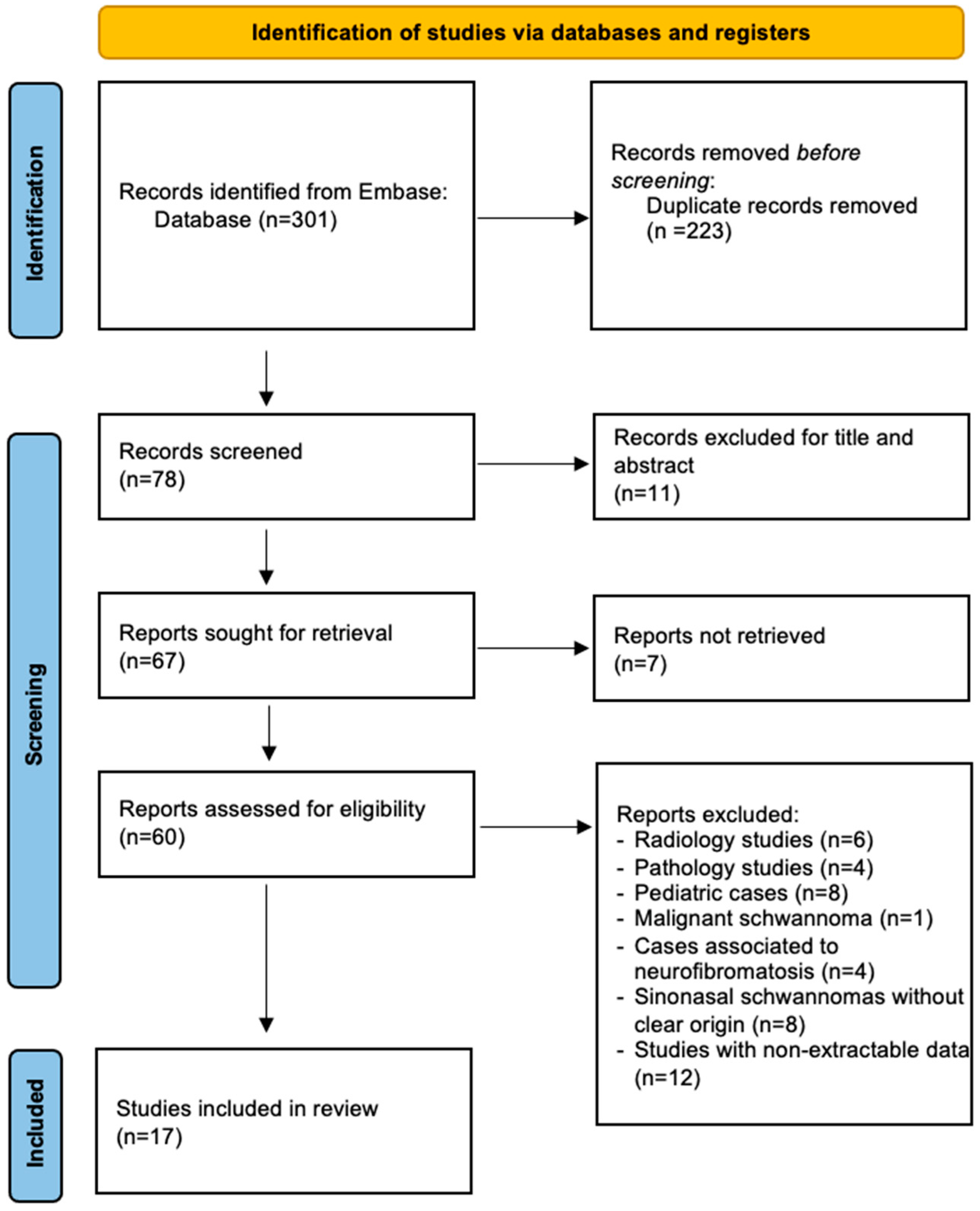

2. Methods

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

- Patients and pathology features (Table 3)

- Treatment and outcome findings (Table 4)

4. Discussion

Limitation of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Corvino, S.; Maiuri, F.; Boido, B.; Iannuzzo, G.; Caggiano, C.; Caiazzo, P. Intraventricular schwannomas. A case report and literature review. Interdiscip. Neurosurg. 2022, 28, 101491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Pan, S.; Alonso, F.; Dekker, S.E.; Bambakidis, N.C. Intracranial Facial Nerve Schwannomas: Current Management and Review of Literature. World Neurosurg. 2017, 100, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMonagle, B.; Al-Sanosi, A.; Croxson, G.; Fagan, P. Facial schwannoma: Results of a large case series and review. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2008, 122, 1139–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, M.L.; Link, M.J. Vestibular Schwannomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 381–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corazzelli, G.; Corvino, S.; Marvulli, M.; Cioffi, V.; D’Elia, A.; Meglio, V.; Tafuto, R.; Mastantuoni, C.; Scala, M.R.; Ricciardi, F.; et al. Comprehensive Surgical Management of Thoracic Schwannomas: A Retrospective Multicenter Study on 98 Lesions. Neurosurgery 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerganov, V.; Petrov, M.; Sakelarova, T. Schwannomas of Brain and Spinal Cord. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2023, 1405, 331–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samii, M.; Alimohamadi, M.; Gerganov, V. Surgical Treatment of Jugular Foramen Schwannoma: Surgical Treatment Based on a New Classification. Neurosurgery 2015, 77, 424–432, discussion 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertea, M.; Filip, A.; Huzum, B.; Lunca, S.; Carp, C.; Mitrea, M.; Toader, P.; Luca, S.; Moraru, D.C.; Poroch, V.; et al. Schwannoma of the Upper Limb: Retrospective Study of a Rare Tumor with Uncommon Locations. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, R.T.; Gross, C.W.; Lazar, R.H. Schwannomas of the paranasal sinuses. Case report and clinicopathologic analysis. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1991, 117, 677–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunaryo, P.L.; Svider, P.F.; Husain, Q.; Choudhry, O.J.; Eloy, J.A.; Liu, J.K. Schwannomas of the sinonasal tract and anterior skull base: A systematic review of 94 cases. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2014, 28, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.Y.; Lee, H.S.; Kang, B.H. Nasal Cavity Schwannoma—A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Ear Nose Throat J. 2024, 103, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corvino, S.; de Divitiis, O.; Iuliano, A.; Russo, F.; Corazzelli, G.; Cohen, D.; Di Crescenzo, R.M.; Palmiero, C.; Pontillo, G.; Staibano, S.; et al. Biphenotypic Sinonasal Sarcoma with Orbital Invasion: A Literature Review and Modular System of Surgical Approaches. Cancers 2024, 16, 3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corvino, S.; Corazzelli, G.; Mariniello, G.; Iuliano, A.; Altieri, R.; Pontillo, G.; Strianese, D.; Barbarisi, M.; Elefante, A.; de Divitiis, O. Biphenotypic Sinonasal Sarcoma: Literature Review of a Peculiar Pathological Entity—The Neurosurgical Point of View. Cancers 2024, 16, 3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, M.; Policeni, B. Sinonasal Neoplasms. Semin. Roentgenol. 2019, 54, 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, T.; Miyawaki, S.; Teranishi, Y.; Ohara, K.; Hirano, Y.; Ogawa, S.; Torazawa, S.; Sakai, Y.; Hongo, H.; Ono, H.; et al. Current molecular understanding of central nervous system schwannomas. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2025, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helbing, D.L.; Schulz, A.; Morrison, H. Pathomechanisms in schwannoma development and progression. Oncogene 2020, 39, 5421–5429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, T.F.; Patel, B.; Khan, S.M.; Mullins, R.D.Z.; Yim, A.K.Y.; Pugazenthi, S.; Mahlokozera, T.; Zipfel, G.J.; Herzog, J.A.; Chicoine, M.R.; et al. Single-cell multi-omic analysis of the vestibular schwannoma ecosystem uncovers a nerve injury-like state. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.J.; Casey-Clyde, T.; Cho, N.W.; Swinderman, J.; Pekmezci, M.; Dougherty, M.C.; Foster, K.; Chen, W.C.; Villanueva-Meyer, J.E.; Swaney, D.L.; et al. Epigenetic reprogramming shapes the cellular landscape of schwannoma. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, D.A.; Hanemann, C.O. Schwannomas and their pathogenesis. Brain Pathol. 2014, 24, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zovickian, J.; Barba, D.; Alksne, J.F. Intranasal schwannoma with extension into the intracranial compartment: Case report. Neurosurgery 1986, 19, 813–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enion, D.S.; Jenkins, A.; Miles, J.B.; Diengdoh, J.V. Intracranial extension of a naso-ethmoid schwannoma. J. Laryngol. Otol. 1991, 105, 578–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bavetta, S.; McFall, M.R.; Afshar, F.; Hutchinson, I. Schwannoma of the anterior cranial fossa and paranasal sinuses. Br. J. Neurosurg. 1993, 7, 697–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatscher, S.; Love, S.; Coakham, H.B. Giant nasal schwannoma with intracranial extension. Case illustration. J. Neurosurg. 1998, 89, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Tyagi, I.; Banerjee, D.; Pandey, R. Nasoethmoid schwannoma with intracranial extension. Case Rep. Rev. Lit. Neurosurg. Rev. 1998, 21, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, M.G.; Jennings, E.; Moraes, O.J.; Santos, M.T.; Zanon, N.; Mattos, B.J.; Belmonte Netto, L. Naso-ethmoid schwannoma with intracranial extension: Case report. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 2001, 59, 421–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquini, E.; Sciarretta, V.; Farneti, G.; Ippolito, A.; Mazzatenta, D.; Frank, G. Endoscopic endonasal approach for the treatment of benign schwannoma of the sinonasal tract and pterygopalatine fossa. Am. J. Rhinol. 2002, 16, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, K.J.; Price, R. Nasoethmoid schwannoma with intracranial extension. Case Rep. Rev. Lit. Br. J. Neurosurg. 2009, 23, 83–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, J.D.; Ramakrishnan, V.R.; Zhang, P.J.; Wu, A.W.; Wang, M.B.; Palmer, J.N.; Chiu, A.G. Diagnosis and endoscopic management of sinonasal schwannomas. ORL J. Otorhinolaryngol. Relat. Spec. 2011, 73, 308–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, D.M.; Husain, Q.; Kanumuri, V.V.; Svider, P.F.; Eloy, J.A.; Liu, J.K. Endoscopic endonasal resection of sinonasal and anterior skull base schwannomas. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2014, 21, 1419–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Xing, G.; Gao, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, F.; Lu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Qian, X. Schwannoma of the Sinonasal Tract and the Pterygopalatine Fossa with or without Intracranial Extension. ORL J. Otorhinolaryngol. Relat. Spec. 2015, 77, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, C.S.; Pomeraniec, I.J.; Starke, R.M.; Shaffrey, M.E. Nasoethmoid schwannoma with intracranial extension. Case report and review of the literature. Br. J. Neurosurg. 2018, 32, 565–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichberg, D.G.; Menaker, S.A.; Buttrick, S.S.; Gultekin, S.H.; Komotar, R.J. Nasoethmoid Schwannoma with Intracranial Extension: A Case Report and Comprehensive Review of the Literature. Cureus 2018, 10, e3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narang, A.; Aggarwal, V.; Jain, R.; Maheshwari, C.; Ramesh, A.; Singh, G. Nasoethmoidal Schwannoma as a Mimicar of Esthesioneuroblastoma: A Case Report and Literature Review. Neurol. India 2022, 70, 784–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogister, F.; Peigneux, N.; Tombu, S. Ethmoid Schwannoma: About the management of a rare tumor of sinonasal cavities manifested by an orbital complication. B-ENT 2021, 17, 260–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahmbhatt, P.; Kumar, T.; Bhatt, A.A.; Vibhute, P.; Patel, V.; Desai, A.; Gupta, V.; Agarwal, A. Sinonasal Schwannomas: Imaging Findings and Review of Literature. Ear Nose Throat J. 2023, 1455613221150573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachicha, A.; Chouchane, H.; Turki, S. Schwannoma of the nasal cavity: A case report and review of the literature. SAGE Open Med. Case Rep. 2024, 12, 2050313X241272687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, K.; Yoshida, K.; Miwa, T.; Ikeda, E.; Kawase, T. Olfactory schwannoma. Acta Neurochir. 2007, 149, 605–610, discussion 610–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoneoka, Y.; Akiyama, K.; Seki, Y.; Hasegawa, G.; Kakita, A. Frontoethmoidal Schwannoma with Exertional Cerebrospinal Fluid Rhinorrhea: Case Report and Review of Literature. World Neurosurg. 2018, 111, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, C.H.; Kim, J. CT and MR imaging findings of sinonasal schwannoma: A review of 12 cases. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2013, 34, 628–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Wesseling, P.; Brat, D.J.; Cree, I.A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Hawkins, C.; Ng, H.K.; Pfister, S.M.; Reifenberger, G.; et al. The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: A summary. Neuro Oncol. 2021, 23, 1231–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buob, D.; Wacrenier, A.; Chevalier, D.; Aubert, S.; Quinchon, J.F.; Gosselin, B.; Leroy, X. Schwannoma of the sinonasal tract: A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 5 cases. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2003, 127, 1196–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, B.L.; Van Sandt, M.; Loyo, M. Encapsulated Sinonasal Schwannoma. Ear Nose Throat J. 2019, 98, 205–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, S.L.; Mentzel, T.; Fletcher, C.D. Schwannomas of the sinonasal tract and nasopharynx. Mod. Pathol. 1997, 10, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sheikh, H.Y.; Chakravarthy, R.P.; Slevin, N.J.; Sykes, A.J.; Banerjee, S.S. Benign schwannoma in paranasal sinuses: A clinico-pathological study of five cases, emphasising diagnostic difficulties. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2008, 122, 598–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forer, B.; Lin, L.J.; Sethi, D.S.; Landsberg, R. Endoscopic Resection of Sinonasal Tract Schwannoma: Presentation, Treatment, and Outcome in 10 Cases. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2015, 124, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogunleye, A.O.; Ijaduola, G.T.; Malomo, A.O.; Oluwatosin, O.M.; Shokunbi, W.A.; Akinyemi, O.A.; Oluwasola, A.O.; Akang, E.E. Malignant schwannoma of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses in a Nigerian. Afr. J. Med. Med. Sci. 2006, 35, 489–493. [Google Scholar]

- Mariniello, G.; de Divitiis, O.; Corvino, S.; Strianese, D.; Iuliano, A.; Bonavolontà, G.; Maiuri, F. Recurrences of spheno-orbital meningiomas: Risk factors and management. World Neurosurg. 2022, 161, E514–E522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariniello, G.; Corvino, S.; Corazzelli, G.; de Divitiis, O.; Fusco, G.; Iuliano, A.; Strianese, D.; Briganti, F.; Elefante, A. Spheno-Orbital Meningiomas: The Rationale behind the Decision-Making Process of Treatment Strategy. Cancers 2024, 16, 2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffau, H.; Berger, M.; Brastianos, P.K.; Sanai, N.; Mandonnet, E.; McKhann, G.M. Introduction: Contemporary management of low-grade gliomas: From tumor biology to the patient’s quality of life. Neurosurg. Focus 2024, 56, E1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffau, H.; Mandonnet, E. The “onco-functional balance” in surgery for diffuse low-grade glioma: Integrating the extent of resection with quality of life. Acta Neurochir. 2013, 155, 951–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffau, H. Brain connectomics applied to oncological neuroscience: From a traditional surgical strategy focusing on glioma topography to a meta-network approach. Acta Neurochir. 2021, 163, 905–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldbrunner, R.; Weller, M.; Regis, J.; Lund-Johansen, M.; Stavrinou, P.; Reuss, D.; Evans, D.G.; Lefranc, F.; Sallabanda, K.; Falini, A.; et al. EANO guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of vestibular schwannoma. Neuro Oncol. 2020, 22, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassam, A.; Snyderman, C.H.; Mintz, A.; Gardner, P.; Carrau, R.L. Expanded endonasal approach: The rostrocaudal axis. Part I. Crista galli to the sella turcica. Neurosurg. Focus 2005, 19, E3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassam, A.; Snyderman, C.H.; Mintz, A.; Gardner, P.; Carrau, R.L. Expanded endonasal approach: The rostrocaudal axis. Part II. Posterior clinoids to the foramen magnum. Neurosurg. Focus 2005, 19, E4. [Google Scholar]

- Klossek, J.M.; Ferrie, J.C.; Goujon, J.M.; Azais, O.; Poitout, F.; Babin, P.; Fontanel, J.P. Nasosinusal schwannoma. Apropos of 2 cases. Value of nasal endoscopy for diagnosis and treatment. Ann. Otolaryngol. Chir. Cervicofac. 1993, 110, 341–345. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, V.; Deans, J.A.; Nicol, A. Sphenoid sinus schwannoma treated by endoscopic excision. J. Laryngol. Otol. 1999, 113, 466–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardesty, D.A.; Montaser, A.; Kreatsoulas, D.; Shah, V.S.; VanKoevering, K.K.; Otto, B.A.; Carrau, R.L.; Prevedello, D.M. Complications after 1002 endoscopic endonasal approach procedures at a single center: Lessons learned, 2010–2018. J. Neurosurg. 2021, 136, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassam, A.; Carrau, R.L.; Snyderman, C.H.; Gardner, P.; Mintz, A. Evolution of reconstructive techniques following endoscopic expanded endonasal approaches. Neurosurg. Focus 2005, 19, E8. [Google Scholar]

- Hadad, G.; Bassagasteguy, L.; Carrau, R.L.; Mataza, J.C.; Kassam, A.; Snyderman, C.H.; Mintz, A. A novel reconstructive technique after endoscopic expanded endonasal approaches: Vascular pedicle nasoseptal flap. Laryngoscope 2006, 116, 1882–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medel, R.; España, J.C.S.; Martín, F.Z. The Medial Transorbital Approach. In Cranio-Orbital Mass Lesions; Bonavolontà, G., Maiuri, F., Mariniello, G., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Scholfield, D.W.; Levyn, H.; Tabar, V.S.; Ganly, I.; Della Rocca, D.; Cohen, M.A. The medial transorbital approach in cranioendoscopic skull base tumor resections for locally advanced tumors. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2024, 119, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corvino, S.; Villanueva-Solórzano, P.; Offi, M.; Armocida, D.; Nonaka, M.; Iaconetta, G.; Esposito, F.; Cavallo, L.; de Notaris, M. A New Perspective on the Cavernous Sinus as Seen through Multiple Surgical Corridors: Anatomical Study Comparing the Transorbital, Endonasal, and Transcranial Routes and the Relative Coterminous Spatial Regions. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corvino, S.; Sacco, M.; Somma, T.; Berardinelli, J.; Ugga, L.; Colamaria, A.; Corrivetti, F.; Iaconetta, G.; Kong, D.-S.; de Notaris, M. Functional and clinical outcomes after superior eyelid transorbital endoscopic approach for spheno-orbital meningiomas: Illustrative case and literature review. Neurosurg. Rev. 2023, 46, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Corvino, S.; Armocida, D.; Offi, M.; Pennisi, G.; Burattini, B.; Mondragon, A.V.; Esposito, F.; Cavallo, L.M.; de Notaris, M. The anterolateral triangle as window on the foramen lacerum from transorbital corridor: Anatomical study and technical nuances. Acta Neurochir. 2023, 165, 2407–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corvino, S.; Guizzardi, G.; Sacco, M.; Corrivetti, F.; Bove, I.; Enseñat, J.; Colamaria, A.; Prats-Galino, A.; Solari, D.; Cavallo, L.M.; et al. The feasibility of three port endonasal, transorbital, and sublabial approach to the petroclival region: Neurosurgical audit and multiportal anatomic quantitative investigation. Acta Neurochir. 2023, 165, 1821–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corvino, S.; de Notaris, M.; Sommer, D.; Kassam, A.; Kong, D.S.; Piazza, A.; Corrivetti, F.; Cavallo, L.M.; Iaconetta, G.; Reddy, K. Assessing The Feasibility of Selective Piezoelectric Osteotomy in Transorbital Approach to The Middle Cranial Fossa: Anatomical and Quantitative Study and Surgical Implications. World Neurosurg. 2024, 192, e198–e209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corvino, S.; Kassam, A.; Piazza, A.; Corrivetti, F.; Esposito, F.; Iaconetta, G.; de Notaris, M. Navigating the Intersection Between the Orbit and the Skull Base: The “Mirror” McCarty Keyhole During Transorbital Approach: An Anatomic Study With Surgical Implications. Oper. Neurosurg. 2024, 28, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corvino, S.; Kassam, A.; Piazza, A.; Corrivetti, F.; Spiriev, T.; Colamaria, A.; Cirrottola, G.; Cavaliere, C.; Esposito, F.; Cavallo, L.M.; et al. Open-door extended endoscopic transorbital technique to the paramedian anterior and middle cranial fossae: Technical notes, anatomomorphometric quantitative analysis, and illustrative case. Neurosurg. Focus 2024, 56, E7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors/Year | Num. of Cases | Sex, Age (Years) | Presenting Symptoms | Anatomical Origin | Intracranial Extension | Orbit Involvement | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Zovickian et al. [21] 1986 | 1 | M, 40 | Nasal obstruction, headache | ES | Yes/ACF | Not |

| 2 | Enion et al. [22] 1991 | 1 | M, 28 | Headache, nausea, vomiting, epilepsy, blurred vision | ES | Yes/ACF | Not |

| 3 | Bavetta et al. [23] 1993 | 1 | M, 41 | Anosmia, nasal obstruction, blurred vision, diplopia, proptosis | ES-SS-FS | Yes/ACF | Yes |

| 4 | Gatscher et al. [24] 1998 | 1 | F,50 | Anosmia, headache, visual disfunction | ES | Yes | Not |

| 5 | Sharma et al. [25] 1998 | 1 | M, 35 | Anosmia, nasal obstruction, epistaxis, epilepsy | ES | Yes/ACF | Not |

| 6 | Siqueira et al. [26] 2001 | 1 | F, 40 | Anosmia, headache | ES | Yes/ACF | Not |

| 7 | Pasquini et al. [27] 2002 | 1 | F, 75 | Nasal obstruction | ES | None | Not |

| 8 | George et al. [28] 2009 | 1 | F, 27 | Blurred vision, headache | ES | Yes | Yes |

| 9 | Suh et al. [29] 2011 | 3 | M, 51 | Nasal obstruction, headache | ES | None | Not |

| F, 68 | Nasal obstruction, headache | ES | None | Not | |||

| F, 49 | Headache | ES | None | Not | |||

| 10 | Blake et al. [30] 2014 | 1 | M, 62 | Hyposmia Hypogeusia | ES | Yes/ACF | Not |

| 11 | Zhou et al. [31] 2015 | 3 | M, 32, | Nasal obstruction, hyposmia | L MS/ES/SS/NC; NS | None | Not |

| F, 57 | Nasal obstruction | R. MS/ES/SS/NC | |||||

| F, 42 | Nasal obstruction, headache | R. ES/NC; | |||||

| 12 | Hong et al. [32] 2016 | 1 | M, 24 | Asymptomatic | ES | Yes/ACF | Not |

| 13 | Eichberg et al. [33] 2017 | 1 | M, 41 | Anosmia, headache | ES | Yes/ACF | Not |

| 14 | Narang et al. [34] 2019 | 1 | F, 33 | L. proptosis, epistaxis | ES | Yes | Yes |

| 15 | Rogister et al. [35] 2021 | 1 | M. 72 | Right orbital cellulitis | ES | None | Yes |

| 16 | Brahmbhatt et al. [36] 2023 | 5 | 3F, 2M (mean age 48 yrs) | Headache, Fullness Nasal Obstruction Dizziness, Nonspecific Neurologic | 5 ES | 5 Yes | 5 Not |

| 17 | Hachicha et al. [37] 2024 | 1 | F, 22 | Nasal obstruction, hyposmia, epistaxis | ES-SS | None | Not |

| Authors/ Year | Num. of Cases | Time to Treatment | Type of Treatment | Type of Surgical Approach | EOR | Reconstruction | Peri-Post Operative Complications | Recurrence | Status at Last f.u. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Zovickian et al. [21] 1986 | 1 | n.a. | S | FC + EEA | GTR | n.a. | None | n.a. | n.a. |

| 2 | Enion et al. [22] 1991 | 1 | 9 months | S | BFC | GTR | graft of lyophilized dura. | CSF leak | n.a. | Alive 3 mo |

| 3 | Bavetta et al. [23] 1993 | 1 | 36 months | Biopsy- S | FC + EEA | GTR | split skin graft, pericranial flap and lyodura | Enophthalmos, hematoma. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 4 | Gatscher et al. [24] 1998 | 1 | 36 months | S | BFC | GTR | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 5 | Sharma et al. [25] 1998 | 1 | 60 months | S | BFC | GTR | vascularised pericranial flap. | CSF leak | None | Alive 6 mo |

| 6 | Siqueira et al. [26] 2001 | 1 | 36 months | S | BFC + Lateral rhinotomy | GTR | n.a. | None | None | Alive 5 yrs |

| 7 | Pasquini et al. [27] 2002 | 1 | 6 months | S | EEA | GTR | n.a. | n.a. | None | Alive 55 mo. |

| 8 | George et al. [28] 2009 | 1 | 6 months | S | FC | GTR | Tisseel Gortex | CSF leak | None | Alive 3 mo. |

| 9 | Suh et al. [29] 2011 | 3 | n.a. | S | EEA | GTR | n.a. | n.a. | None | Alive 13 mo |

| n.a. | S | EEA | GTR | n.a. | n.a. | None | Alive 53 mo. | |||

| n.a. | S | EEA | GTR | n.a. | n.a. | None | Alive 6 mo | |||

| 10 | Blake et al. [30] 2014 | 1 | 4 months | biopsy- S | EEA | GTR | fascia lata, dermal allograft, vascularized nasoseptal flap | None | None | Alive 5 mo. |

| 11 | Zhou et al. [31] 2015 | 3 | n.a. | 3 S | 1 FESS | 3 GTR | n.a. | None | None | 3 Alive (mean 5 yrs) |

| 1 FESS | ||||||||||

| 1 FESS + LR | ||||||||||

| 12 | Hong et al. [32] 2016 | 1 | Incidental | S | BFC | GTR | Autologous muscle graft, free pericranial graft, and synthetic dura substitute. | CSF leak, meningitis, frontal abscess | n.a. | n.a. |

| 13 | Eichberg et al. [33] 2017 | 1 | Several months | S | BFC | GTR | Pericranial flap, watertight dural closure | None | None | Alive 1 yrs |

| 14 | Narang et al. [34] 2019 | 1 | 3 months | S | BFC + EEA | GTR | Pericranial flap, abdominal free fat graft, mucosa, fibrin glue | None | None | Alive 7 mo. |

| 15 | Rogister et al. [35] 2021 | 1 | n.a. | S | EEA | GTR | n.a. | n.a. | None | Alive 8 mo. |

| 16 | Brahmbhatt et al. [36] 2023 | 5 | n.a. | 5 S | 4 EEA 1 FC | 5 GTR | n.a. | 1 CSF leak 4 None | 5 None | n.a. |

| 17 | Hachicha et al. [37] 2024 | 1 | n.a. | biopsy- S | EEA | GTR | n.a. | None | None | Alive 20 mo. |

| Covariates | Overall Sample 25 (%) | Statistical Analysis (p Value) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic and clinical data | ||

Sex

| 13/25 (52%) 12/25 (48%) | p = 1.0 |

| Age range (median) | 22–75 years (40.2 y.o.) | S-W = 0.93; p = 0.23 |

Main presenting symptoms

| 16/25 (64%) 15/25 (60%) 6/25 (24%) 6/25 (24%) | p = 0.57 |

| Time to treatment (mean ± SD) | 9/25 * (36%) 21 mo. | S-W = 0.847; p = 0.09 |

| Radiological data | ||

Orbital involvement

| 4/25 (16%) 21/25 (84%) | p < 0.01 |

Skull Base involvement

| 16/25 (64%) 9/25 (36%) | p = 0.89 |

| Covariates | Overall Sample 25 (%) | Statistical Analysis (p Value) |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment Data | ||

Type of treatment

| 25/25 (100%) | |

Type of surgical approach

| 11/25 (44%) 7/25 (28%) 2/25 (8%) 5/25 (20%) | p = 0.12 |

EOR

| 25/25 (100%) | |

Peri and postop complications

| 19/25 * (76%) 6/19 (32%) 13/19 (68%) | p = 0.06 |

| Outcome | ||

Recurrence

| 21/25 * (84%) 0/21(0%) 21/21 (100%) | - |

Status

| 16/25 * (64%) 16/16 (100%) | - |

| Follow-up (mean ± SD) | 15.33 (±18.67) | S-W = 0.65; p < 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Corvino, S.; de Divitiis, O.; Corazzelli, G.; Berardinelli, J.; Iuliano, A.; Di Domenico, C.; Lanni, V.; Altieri, R.; Strianese, D.; Elefante, A.; et al. Naso-Ethmoidal Schwannoma: From Pathology to Surgical Strategies. Cancers 2025, 17, 1068. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17071068

Corvino S, de Divitiis O, Corazzelli G, Berardinelli J, Iuliano A, Di Domenico C, Lanni V, Altieri R, Strianese D, Elefante A, et al. Naso-Ethmoidal Schwannoma: From Pathology to Surgical Strategies. Cancers. 2025; 17(7):1068. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17071068

Chicago/Turabian StyleCorvino, Sergio, Oreste de Divitiis, Giuseppe Corazzelli, Jacopo Berardinelli, Adriana Iuliano, Chiara Di Domenico, Vittoria Lanni, Roberto Altieri, Diego Strianese, Andrea Elefante, and et al. 2025. "Naso-Ethmoidal Schwannoma: From Pathology to Surgical Strategies" Cancers 17, no. 7: 1068. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17071068

APA StyleCorvino, S., de Divitiis, O., Corazzelli, G., Berardinelli, J., Iuliano, A., Di Domenico, C., Lanni, V., Altieri, R., Strianese, D., Elefante, A., & Mariniello, G. (2025). Naso-Ethmoidal Schwannoma: From Pathology to Surgical Strategies. Cancers, 17(7), 1068. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17071068