Promoting Physical Activity to Cancer Survivors in Practice: Challenges and Solutions for Implementation

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Data Analysis

| Discussion Guide | |

|---|---|

|

3. Results

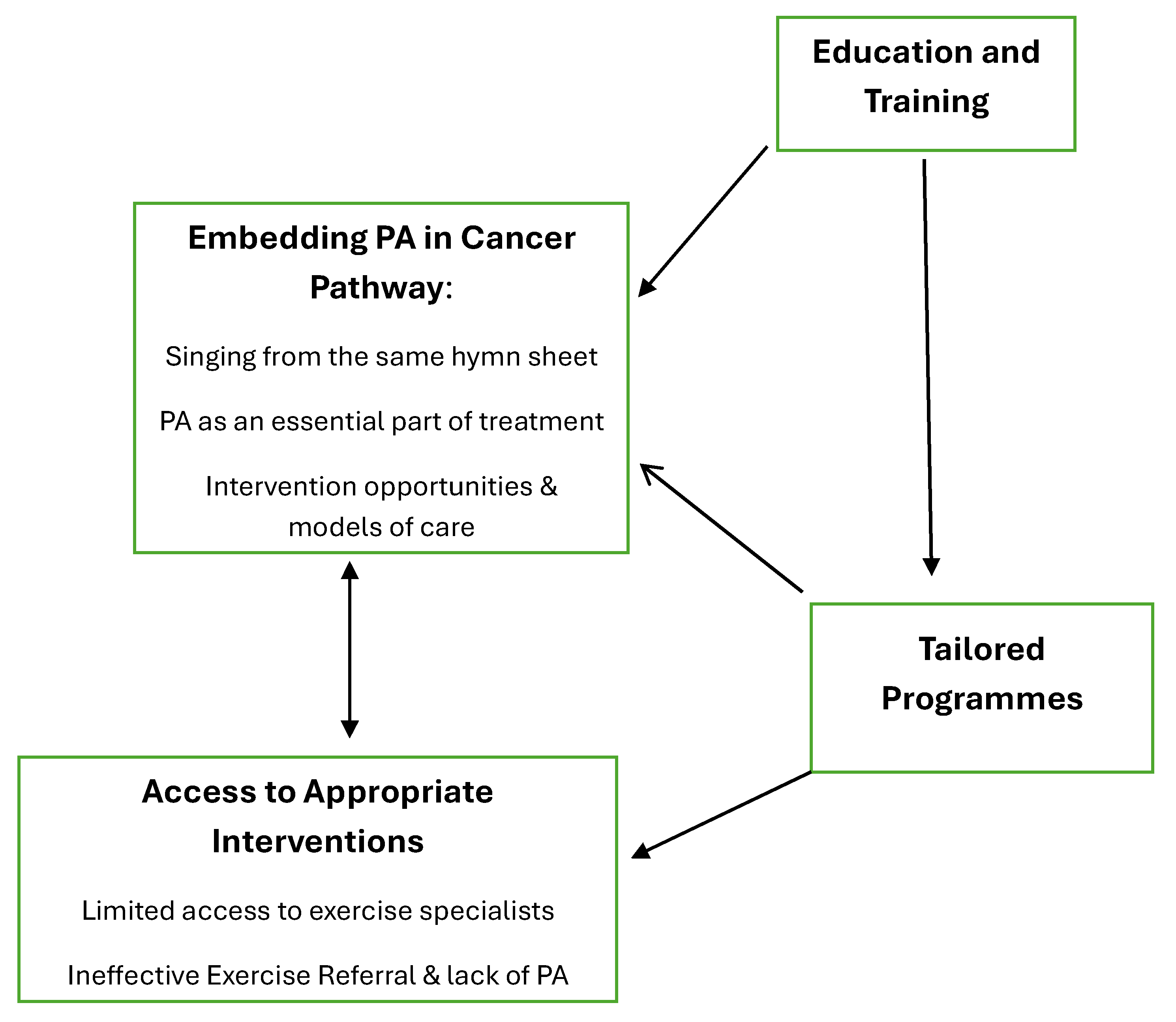

3.1. Embedding PA into the Cancer Pathway

3.1.1. Singing from the Same Hymn Sheet

3.1.2. PA as an Essential Element of Treatment

3.1.3. Intervention Opportunities and Models of Care

3.2. Education and Training

3.3. Access to Appropriate PA Interventions

3.3.1. Limited Access to Exercise Specialists

3.3.2. Ineffective Exercise Referral and Lack of PA Services

3.4. Tailored Programmes

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mctiernan, A.; Friedenreich, C.M.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Powell, K.E.; Macko, R.; Buchner, D.; Pescatello, L.S.; Bloodgood, B.; Tennant, B.; Vaux-Bjerke, A.; et al. Physical activity in cancer prevention and survival: A systematic review. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 1252–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morishita, S.; Hamaue, Y.; Fukushima, T.; Tanaka, T.; Fu, J.B.; Nakano, J. Effect of exercise on mortality and recurrence in patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2020, 19, 1534735420917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz, K.H.; Campbell, A.M.; Stuiver, M.M.; Pinto, B.M.; Schwartz, A.L.; Morris, G.S.; Ligibel, J.A.; Cheville, A.; Galvão, D.A.; Alfano, C.M.; et al. Exercise is Medicine in Oncology: Engaging clinicians to help patients move through cancer. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 468–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedenreich, C.M.; Stone, C.R.; Cheung, W.Y.; Hayes, S.C. Physical activity and mortality in cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2019, 4, pkz080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keats, M.R.; Cui, Y.; Grandy, S.A.; Parker, L. Cardiovascular disease and physical activity in adult cancer survivors: A nested retrospective study from the Atlantic PATH cohort. J. Cancer Surviv. 2017, 11, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, C.L.; Thomson, C.A.; Sullivan, K.R.; Howe, C.L.; Kushi, L.H.; Caan, B.J.; Neuhouser, M.L.; Bandera, E.V.; Wang, Y.; Robien, K.; et al. American Cancer Society nutrition and physical activity guideline for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022, 72, 230–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K.L.; Winters-Stone, K.M.; Wiskemann, J.; May, A.M.; Schwartz, A.L.; Courneya, K.S.; Zucker, D.S.; Matthews, C.E.; Ligibel, J.A.; Gerber, L.H.; et al. Exercise guidelines for cancer survivors: Consensus statement from international multidisciplinary roundtable. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 2375–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, A.; Foster, J.; Stevinson, C.; Cavil, N. The Importance of Physical Activity for People Living with and Beyond Cancer: A Concise Evidence Review; Macmillan: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Arem, H.; Mama, S.K.; Duan, X.; Rowland, J.H.; Bellizzi, K.M.; Ehlers, D.K. Prevalence of Healthy Behaviors among Cancer Survivors in the United States: How Far Have We Come? Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2020, 29, 1179–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardcastle, S.J.; Cohen, P.A. Effective Physical Activity Promotion to Survivors of Cancer Is Likely to Be Home Based and to Require Oncologist Participation. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 3635–3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, K.A.; Estabrooks, C.A.; Olson, K.; Cumming, C. Information acquisition for women facing surgical treatment for breast cancer: Influencing factors and selected outcomes. Patient Educ. Couns. 2007, 69, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardcastle, S.J.; Galliott, M.; Lynch, B.M.; Nguyen, N.H.; Cohen, P.A.; Mohan, G.R.; Johansen, N.J.; Saunders, C. ‘If I Had Someone Looking Over My Shoulder…’: Exploration of Advice Received and Factors Influencing Physical Activity Among Non-metropolitan Cancer Survivors. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2019, 26, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, A.; Williams, K.; Beeken, R. Recall of physical activity advice was associated with higher levels of physical activity in colorectal cancer patients. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e006853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarasenko, Y.N.; Miller, E.A.; Chen, C.; Schoenberg, N.E. Physical activity levels and counseling by health care providers in cancer survivors. Prev. Med. 2017, 99, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardcastle, S.J.; Kane, R.; Chivers, P.; Hince, D.; Dean, A.; Higgs, D.; Cohen, P.A. Knowledge, attitudes, and practice of oncologists and oncology health care providers in promoting physical activity to cancer survivors: An international survey. Support Care Cancer 2018, 26, 3711–3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadler, M.; Bainbridge, D.; Tomasone, J.; Cheifetz, O.; Juergens, R.A.; Sussman, J. Oncology care provider perspectives on exercise promotion in people with cancer: An examination of knowledge, practices, barriers, and facilitators. Support Care Cancer 2017, 25, 2297–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantwell, M.; Walsh, D.; Furlong, B.; Moyna, N.; McCaffrey, N.; Boran, L.; Smyth, S.; Woods, C. Healthcare professionals’ knowledge and practice of physical activity promotion in cancer care: Challenges and solutions. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2018, 27, e12795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haussmann, A.; Ungar, N.; Gabrian, M.; Tsiouris, A.; Sieverding, M.; Wiskemann, J.; Steindorf, K. Are healthcare professionals being left in the lurch? The role of structural barriers and information resources to promote physical activity to cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2018, 26, 4087–4096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Turchyn, J.; Richardson, J.; Tozer, R.; McNeely, M.; Thabane, L. Physical activity and breast cancer: A qualitative study on the barriers and facilitators of exercise promotion from the perspective of health care professionals. Physiother. Can. 2016, 68, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A.L.; Potts, H.W.W.; Stevens, C.; Lally, P.; Smith, L.; Fisher, A. Cancer specialist nurses’ perspectives of physical activity promotion and the potential role of physical activity apps in cancer care. J Cancer Surviv. 2019, 13, 815–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avancini, A.; D’Amico, F.; Tregnago, D.; Trestini, I.; Belluomini, L.; Vincenzi, S.; Canzan, F.; Saiani, L.; Milella, M.; Pilotto, S. Nurses’ perspectives on physical activity promotion in cancer patients: A qualitative research. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2021, 55, 102061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, A.J.; Faulkner, G.; Jones, J.M.; Sabiston, C.M. A qualitative analysis of oncology clinicians’ perceptions and barriers for physical activity counseling in breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 2018, 26, 3117–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caperchione, C.M.; Sharp, P.; Phillips, J.L.; Agar, M.; Liauw, W.; Harris, C.A.; Marin, E.; McCullough, S.; Lilian, R. Bridging the gap between attitudes and action: A qualitative exploration of clinician and exercise professional’s perceptions to increase opportunities for exercise counselling and referral in cancer care. Patient Educ. Couns. 2022, 105, 2489–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karvinen, K.H.; Bruner, B.; Truant, T. Lifestyle counseling practices of oncology nurses in the United States and Canada. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2018, 19, 690–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, M.L.K.; Østergren, P.; Kvorning Ternov, K.; Sønksen, J.; Midtgaard, J. Factors related to promotion of physical activity in clinical oncology practice: A scoping review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2023, 107, 107582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbourne, H.; Soo, W.K.; O’Reilly, V.; Moran, A.; Steer, C.B. Exercise as a supportive care strategy in men with prostate cancer receiving androgen deprivation therapy at a regional cancer centre: A survey of patients and clinicians. Support Care Cancer 2022, 30, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokal, K.; Daley, A.J.; Madigan, C.D. “Fear of raising the problem without a solution”: A qualitative study of patients’ and healthcare professionals’ views regarding the integration of routine support for physical activity within breast cancer care. Support Care Cancer 2024, 32, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2021, 13, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, J. A Pragmatic Definition of the Concept of Theoretical Saturation. Sociol. Focus 2019, 52, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.K.; Guassora, A.D. Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies: Guided by Information Power. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Namey, E.; McKenna, K. How Many Focus Groups Are Enough? Building an Evidence Base for Nonprobability Sample Sizes. Field Methods 2017, 29, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, D.J. Choosing a qualitative research method. In Qualitative Research Methods in Mental Health and Psychotherapy: A Guide for Students and Practitioners; Harper, D., Thompson, A.R., Eds.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2011; pp. 83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell-Smith, C.; Zeps, N.; Hagger, M.S.; Platell, C.; Hardcastle, S.J. Barriers to physical activity participation in colorectal cancer survivors at high risk of cardiovascular disease. Psycho-Oncol. 2017, 26, 808–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granger, C.L.; Denehy, L.; Remedios, L.; Retica, S.; Phongpagdi, P.; Hart, N.; Parry, S.M. Barriers to translation of physical activity into the lung cancer model of care. A qualitative study of clinicians’ perspective. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2016, 3, 2215–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-Onge, K.; St-Cyr, J.; Doré, I.; Gauvin, L. Patient and professional perspectives on physical activity promotion in routine cancer care: A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell-Smith, C.; Hagger, M.S.; Kane, R.; Cohen, P.A.; Tan, J.; Platell, C.; Makin, G.B.; Saunders, C.; Nightingale, S.; Lynch, C.; et al. Psychological correlates of physical activity and exercise preferences in metropolitan and nonmetropolitan cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncol. 2021, 30, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshahat, S.; Treanor, C.; Donnelly, M. Factors influencing physical activity participation among people living with or beyond cancer: A systematic scoping review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.N.; McAuley, E.; Trinh, L. Physical activity programming and counseling preferences among cancer survivors: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardcastle, S.J.; Maxwell-Smith, C.; Cavalheri, V.; Boyle, T.; Román, M.L.; Platell, C.; Levitt, M.; Saunders, C.; Sardelic, F.; Nightingale, S.; et al. A randomized controlled trial of Promoting Physical Activity in Regional and Remote Cancer Survivors (PPARCS). J. Sport Health Sci. 2024, 13, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelosi, A.C.; Rostirola, G.C.; Pereira, J.S.; Silva, K.C.; Fontanari, M.E.R.; Oliveira, M.S.P.; dos Reis, I.G.M.; Messias, L.H.D. Remote and unsupervised Exercise strategies for improving the physical activity of Colorectal Cancer patients: A Meta-analysis. Healthcare 2023, 11, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 27 (67.5%) | |

| Male | 13 (32.5%) | |

| Participant Role | ||

| Cancer Support Centre Manager | 6 (15.0%) | |

| Physiotherapist | 6 (15.0%) | |

| Oncology Nurse | 5 (12.5%) | |

| Oncologist | 3 (7.5%) | |

| Consumer | 5 (12.5%) | |

| Academic | 5 (12.5.%) | |

| NCCP Representative | 4 (10.0%) | |

| Exercise Specialist | 3 (7.5%) | |

| Other | 3 (7.5%) | |

| Geographical Region | ||

| Dublin | 17 (42.5%) | |

| Galway | 4 (10.0%) | |

| Donegal | 3 (7.5%) | |

| Waterford | 4 (10.0%) | |

| Monaghan | 2 (5.0%) | |

| Cork | 2 (5.0.%) | |

| Wicklow | 2 (5.0%) | |

| Limerick | 1 (2.5%) | |

| Laois | 1 (2.5%) | |

| Kilkenny | 1 (2.5%) | |

| Missing | 3 (7.5%) | |

| Theme | Sub-Themes/Codes | Further Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Embedding PA into the cancer pathway | Singing from the same hymn sheet | “They have to give the same message that exercise is extremely important part of your journey and keep hearing that no matter where they go” (academic, 1) “If a service user comes into your service everyone is telling them the same thing” (breast cancer survivor, 2) “We need all the HCPs within the hospital on board… and the NCCP have a brochure indicating what we should be working towards” (CSC manager, 6) |

| PA as an essential part of treatment | “It really needs to be almost prescribed…I want to see you walking…exercising for at least X amount or at least aiming for it” (breast cancer survivor, 1) “If we could give everyone a Godin leisure time questionnaire…to describe the intensity level of activity they do per week and then using that information to inform what level of support people need” (exercise physiologist, 1). “I’m blue in the face talking about the lifestyle measures that are required…they need to be working towards 30 min a day” (medical oncologist, hospital 12). | |

| Intervention opportunities | “Getting to people early is important because if you wait until they have finished treatment you are missing out on the benefits that accrue during their treatment” (physiotherapist, CSC 6) “I would not estimate the value of your nursing staff…when someone is getting chemotherapy, they’re in the day ward for a number of hours…they’re in the chair talking to the nurses” (academic, 5) “Other patients need help and need assistance and for those patients they need to have, in the same way as it is standard of care for post MI, you go into your Phase II or Phase III your cardiac rehab programme” (physiotherapist, hospital 7) “When someone has their myocardial infarction…the cardiac rehab pathway almost starts straight away” (academic, 4) “The NCCP actually says that all patients should have the opportunity to see psycho-oncology and nobody in Ireland seems to want to take up the psycho-oncology service, patients I mean…the next best thing and maybe even better is exercise” (radiation oncologist, hospital 11) | |

| Education and training | “Walking is one of the preferable forms of exercise, but actually when I get down to the conversation about somebody who [reports] walking every day, when you actually talk to them about it they are not really pushing themselves…They might be walking for an hour a day but not doing the appropriate intensity to get benefit” (ANP, hospital 1) “The understanding of the benefits of exercise for the patients is just…not out there the way it should be…You get into that conversation when….even in our place, well you say go to the gym or…oh I don’t really feel like it, I will do yoga, as if it is comparable, and it is not, you know” (physiotherapist, CSC 6). | |

| Access to appropriate PA interventions | Limited access to exercise specialists | “The amount of people who bounce back to me who couldn’t do their gym registration because once they heard that they had recent cancer treatment, there was a level of hesitancy [in accepting them]” (physiotherapist, hospital 10). |

| Ineffective exercise referral and lack of PA services. | “Healthlink is the software they use and if something was built in there that they could refer to…as a means of referral…sending out paperwork about interventions doesn’t work” (academic, 3) “There should be a referral pathway out to the community, a very strong referral pathway out to the community that are running the specialised programme or that have the expertise…not everyone who comes to us needs that detailed medical assistance…they just need guidance” (manager, CSC 6) “Our research that we did a few years ago showed very clearly that patients wanted to be referred in from the hospital. They had confidence in the hospital staff” (ANP, hospital 3). | |

| Tailored and effective programmes | “Each patient has very individualistic needs…one size doesn’t fit everyone at all. Personalisation is important…also need to address what side effect you’re trying to address and what type of exercise intervention you use to do that” (academic, 4). “We could include exercise for everyone but ensure the level of support is applicable to the individual…whether that is somewhere in their local community or whether they’re completely inactive and having side effects from their treatment and need further support” (exercise physiologist, 1) “They don’t want to sit in with a load of cancer survivors because they don’t identify themselves as cancer survivors. They want to put it behind them and never think about it again” (medical oncologist, Hospital 12) “Being able to offer some kind of triage to get the person to the right service at the end of their treatment” (physiotherapist, hospital 10) “I agree with [name removed] about the group-based programmes that it is not something that you can keep up or sustain, like they run for a certain length of time and then finishes…once the programme finishes, they are not going to sign up for it again so there is limited scope with those” (NCCP, 3). “The point of funding the research in [cancer support] centres was to try and get some sort of an efficacy and the idea being that if we can show efficacy for a programme, then the NCCP might be able to coordinate it nationally and roll it out to all the centres, do a train the trainer model…so that people would be able to avail of the same thing in your local Cancer Support Centre regardless of where you live” (NCCP, 1) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hardcastle, S.; Sheehan, P.; Kehoe, B.; Harrison, M.; Cantwell, M.; Moyna, N. Promoting Physical Activity to Cancer Survivors in Practice: Challenges and Solutions for Implementation. Cancers 2025, 17, 850. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17050850

Hardcastle S, Sheehan P, Kehoe B, Harrison M, Cantwell M, Moyna N. Promoting Physical Activity to Cancer Survivors in Practice: Challenges and Solutions for Implementation. Cancers. 2025; 17(5):850. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17050850

Chicago/Turabian StyleHardcastle, Sarah, Patricia Sheehan, Bróna Kehoe, Michael Harrison, Mairéad Cantwell, and Niall Moyna. 2025. "Promoting Physical Activity to Cancer Survivors in Practice: Challenges and Solutions for Implementation" Cancers 17, no. 5: 850. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17050850

APA StyleHardcastle, S., Sheehan, P., Kehoe, B., Harrison, M., Cantwell, M., & Moyna, N. (2025). Promoting Physical Activity to Cancer Survivors in Practice: Challenges and Solutions for Implementation. Cancers, 17(5), 850. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17050850