Silent Players, Loud Impact: The Influence of lncRNAs on Melanoma Progression

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Molecular Mechanisms Regulated by Long Non-Coding RNA

2.1. Transcriptional Regulation

2.1.1. Long Non-Coding RNA and Chromatin-Modifying Complexes

2.1.2. Long Non-Coding RNA Interaction with Transcription Factors and Co-Activators

2.1.3. Enhancer-Associated lncRNAs and Enhancer RNAs (eRNAs)

2.2. Post-Transcriptional Regulation

2.2.1. Competing Endogenous RNA (ceRNA) Networks: The lncRNA–miRNA–mRNA Axis

2.2.2. Splicing Modulation of Long Non-Coding RNA

2.2.3. Long Non-Coding RNA and Translational Control

2.2.4. Interaction with RNA-Binding Proteins

3. Key lncRNAs in Melanoma Pathogenesis

3.1. Oncogenic lncRNAs

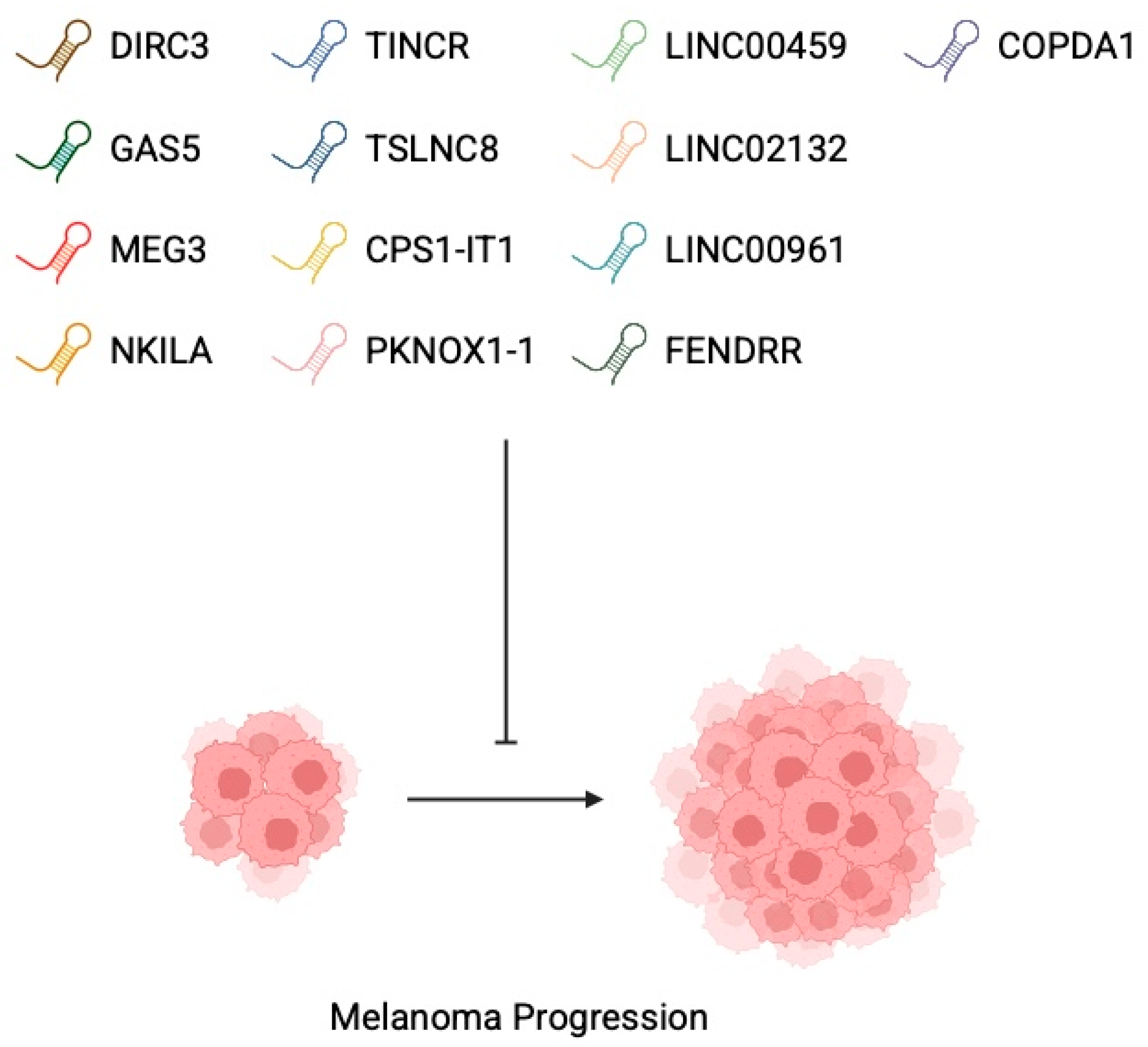

3.2. Tumour-Suppressor lncRNAs

4. Hallmarks of lncRNA Involvement in Melanoma

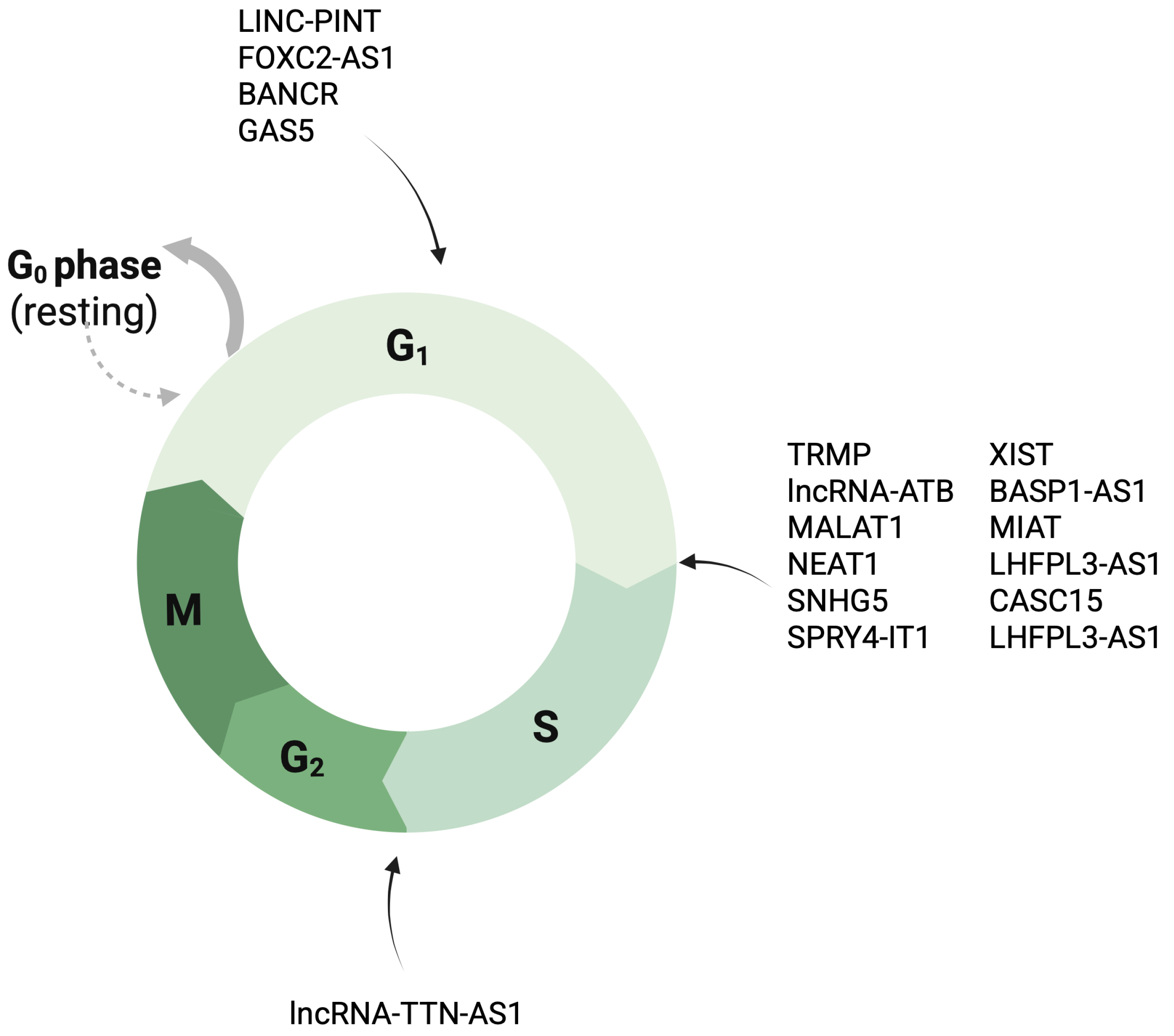

4.1. Cell Proliferation and Cell Cycle Control

4.2. Programmed Cell Death

4.3. EMT Transition

4.4. Angiogenesis

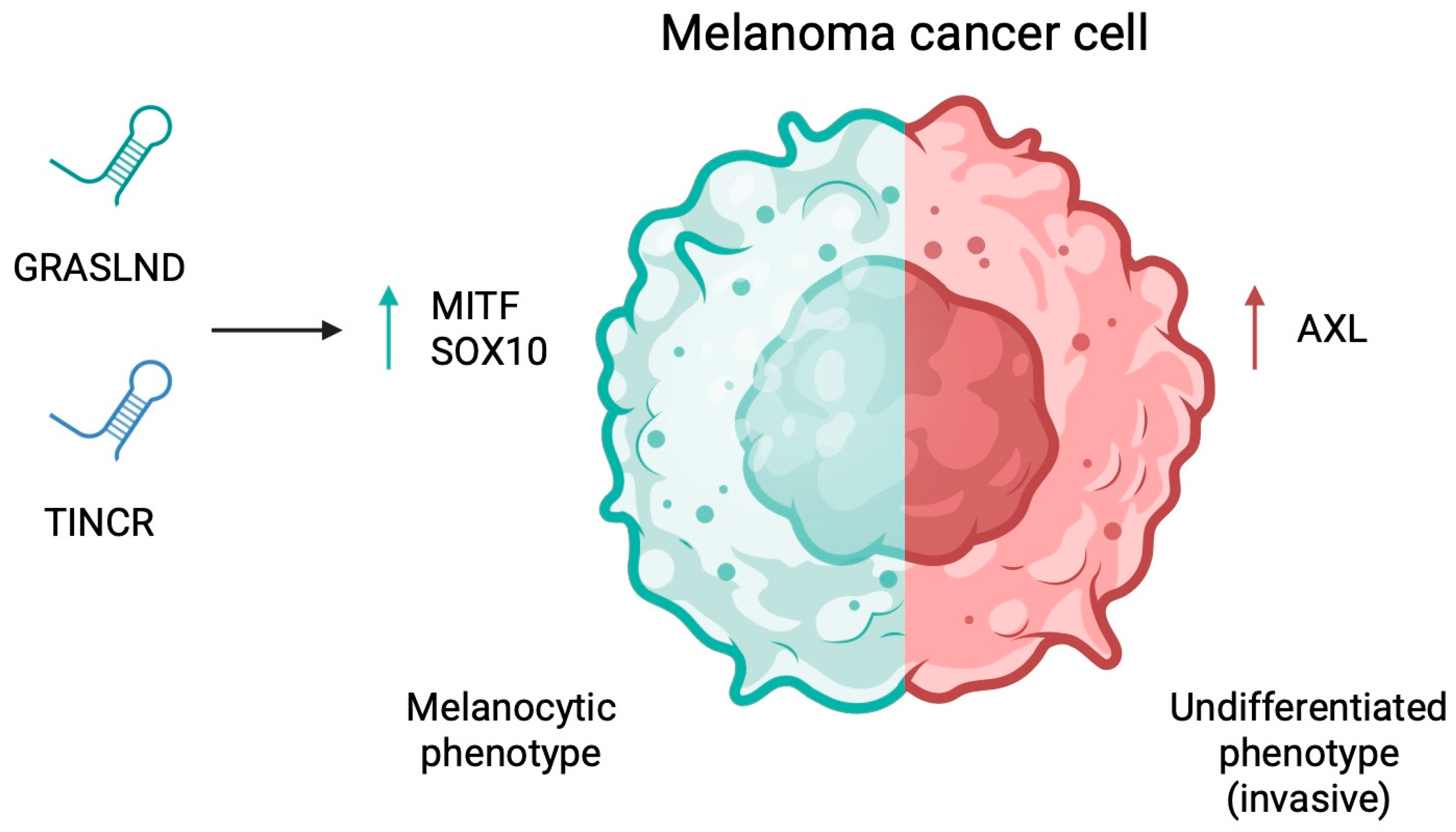

4.5. Cancer Stem Cell Properties and Phenotypic Plasticity

4.6. Metabolic Reprogramming

5. Clinical Value of Long Con-Coding RNA in Melanoma

6. Limitations and Future Areas

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ncRNA | Non-coding RNA |

| lncRNA | Long non-coding RNA |

| miRNA | microRNA |

| UVR | Ultraviolet radiation |

| EZH2 | Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 |

| PRC2 | Polycomb repressive complex 2 |

| eRNA | Enhancer RNA |

| ceRNA | Competing endogenous RNA |

| ATF4 | Activating transcription factor 4 |

| uORF | Upstream open reading frame |

| eIF2α | Eukaryotic initiation factor 2 α subunit |

| EEF2 | Elongation factor 2 |

| BANCR | BRAF-activated non-protein coding RNA |

| HDAC | Histone deacetylase |

| PD-1 | Programmed cell death protein 1 |

| CDK | Cyclin-dependent kinase |

| CDKN1C | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1C |

| MEG3 | Maternally expressed gene 3 |

| EMT | Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition |

| FOXP3 | Forkhead box P3 |

| MDM2 | Mouse double minute 2 homolog |

| HGF | Hepatocyte growth factor |

| TRMP | TP53-regulated modulator of p27 |

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, G.V.; Swetter, S.M.; Menzies, A.M.; Gershenwald, J.E.; Scolyer, R.A. Cutaneous melanoma. Lancet 2023, 402, 485–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, T.; Ottaviano, M.; Arance, A.; Blank, C.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Donia, M.; Dummer, R.; Garbe, C.; Gershenwald, J.E.; Gogas, H.; et al. Cutaneous melanoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2025, 36, 10–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2024. Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/2024/summary/ (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Mattick, J.S.; Amaral, P.P.; Carninci, P.; Carpenter, S.; Chang, H.Y.; Chen, L.L.; Chen, R.; Dean, C.; Dinger, M.E.; Fitzgerald, K.A.; et al. Long non-coding RNAs: Definitions, functions, challenges and recommendations. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023, 24, 430–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kielbowski, K.; Ptaszynski, K.; Wojcik, J.; Wojtys, M.E. The role of selected non-coding RNAs in the biology of non-small cell lung cancer. Adv. Med. Sci. 2023, 68, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouznetsova, V.L.; Tchekanov, A.; Li, X.; Yan, X.; Tsigelny, I.F. Polycomb repressive 2 complex-Molecular mechanisms of function. Protein Sci. 2019, 28, 1387–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, A.; Wang, Y.; Stovall, D.B.; Sui, G. Emerging Roles of LncRNAs in the EZH2-regulated Oncogenic Network. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 17, 3268–3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.F.; Tao, X.H.; Yu, Y.; Teng, Y.; Huang, Y.M.; Ma, J.W.; Fan, Y.B. LncRNA FOXC2-AS1 stimulates proliferation of melanoma via silencing p15 by recruiting EZH2. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 24, 8940–8946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, F.; Heindl, L.M.; He, X.; Yu, J.; Yang, J.; Ge, S.; Ruan, J.; Jia, R.; et al. Long Non-coding RNA LINC-PINT Suppresses Cell Proliferation and Migration of Melanoma via Recruiting EZH2. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouaud, F.; Hamouda-Tekaya, N.; Cerezo, M.; Abbe, P.; Zangari, J.; Hofman, V.; Ohanna, M.; Mograbi, B.; El-Hachem, N.; Benfodda, Z.; et al. E2F1 inhibition mediates cell death of metastatic melanoma. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, K.; Joyce, C.E.; Buquicchio, F.; Brown, A.; Ritz, J.; Distel, R.J.; Yoon, C.H.; Novina, C.D. The lncRNA SLNCR1 Mediates Melanoma Invasion through a Conserved SRA1-like Region. Cell Rep. 2016, 15, 2025–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wozniak, M.; Czyz, M. lncRNAs-EZH2 interaction as promising therapeutic target in cutaneous melanoma. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2023, 10, 1170026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Xiong, F.; Li, W. Enhancer RNAs in cancer: Regulation, mechanisms and therapeutic potential. RNA Biol. 2020, 17, 1550–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Jiang, H.; Liu, J.; Li, D.Y.; Li, B.; Long, Q.R.; Zheng, L.; Gu, H. Comprehensive Analysis of Enhancer RNAs Identifies LINC00689 and ELFN1-AS1 as Novel Prognostic Biomarkers in Uveal Melanoma. Dis. Markers 2022, 2022, 5994800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Li, T.; Liu, L.; Liang, F.; Qi, J.; Liang, P.; Pan, D. Comprehensive transcriptomic analysis of immune-related eRNAs associated with prognosis and immune microenvironment in melanoma. Front. Surg. 2022, 9, 917061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, W.; Li, L.; Shi, Y.; Bu, X.; Xia, Y.; Wang, J.; Djangmah, H.S.; Liu, X.; You, Y.; Xu, B. Long non-coding RNA MALAT1 acts as a competing endogenous RNA to promote malignant melanoma growth and metastasis by sponging miR-22. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 63901–63912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feichtenschlager, V.; Zheng, Y.J.; Ho, W.; Chen, L.; Callanan, C.; Chen, C.; Lee, A.; Ortiz, J.; Rappersberger, K.; Ortiz-Urda, S. Deconstructing the role of MALAT1 in MAPK-signaling in melanoma: Insights from antisense oligonucleotide treatment. Oncotarget 2023, 14, 543–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Barrios, N.; Legascue, M.F.; Benhamed, M.; Ariel, F.; Crespi, M. Splicing regulation by long noncoding RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 2169–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wan, H.; Zhang, X. LncRNA LHFPL3-AS1 contributes to tumorigenesis of melanoma stem cells via the miR-181a-5p/BCL2 pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melixetian, M.; Bossi, D.; Mihailovich, M.; Punzi, S.; Barozzi, I.; Marocchi, F.; Cuomo, A.; Bonaldi, T.; Testa, G.; Marine, J.C.; et al. Long non-coding RNA TINCR suppresses metastatic melanoma dissemination by preventing ATF4 translation. EMBO Rep. 2021, 22, e50852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhang, H.; Guo, X.; Zhu, Z.; Cai, H.; Kong, X. Insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein 1 (IGF2BP1) in cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2018, 11, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosono, Y.; Niknafs, Y.S.; Prensner, J.R.; Iyer, M.K.; Dhanasekaran, S.M.; Mehra, R.; Pitchiaya, S.; Tien, J.; Escara-Wilke, J.; Poliakov, A.; et al. Oncogenic Role of THOR, a Conserved Cancer/Testis Long Non-coding RNA. Cell 2017, 171, 1559–1572.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

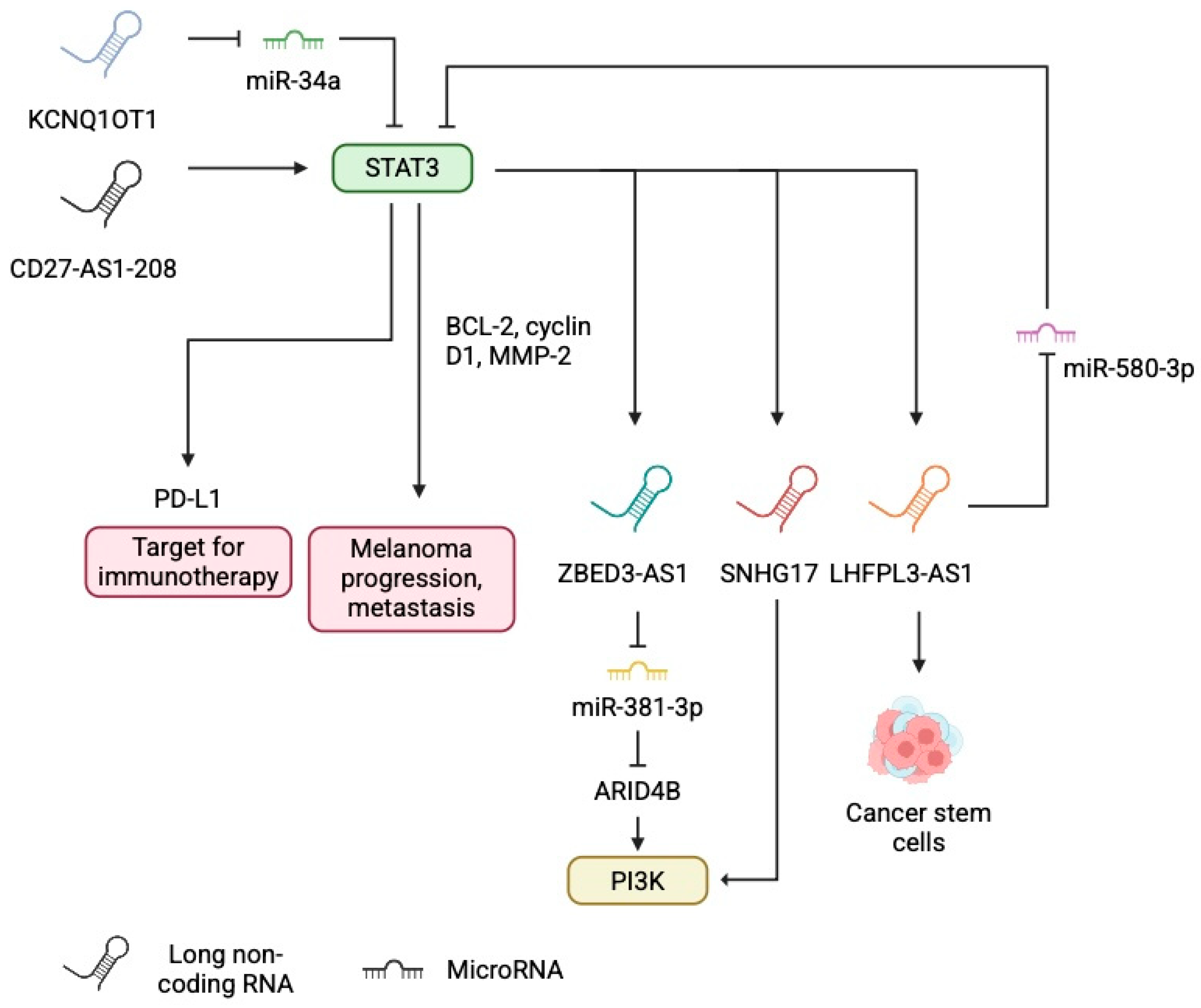

- Ma, J.; Shi, Q.; Guo, S.; Xu, P.; Yi, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Liu, L.; Yue, Q.; et al. Long Non-Coding RNA CD27-AS1-208 Facilitates Melanoma Progression by Activating STAT3 Pathway. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 818178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.L.; Liu, B.; Li, J.K.; Lin, Y.F.; Zhu, P.L.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Deng, B.; Zhang, J.Z.; Yung, K.K. Przewaquinone A, as a natural STAT3 inhibitor, suppresses the growth of melanoma cells and induces autophagy. Phytomedicine 2025, 142, 156810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.X.; Chen, Y.J.; Xu, B.W.; Fu, X.Q.; Ding, W.J.; Li, S.A.; Wang, X.Q.; Wu, J.Y.; Wu, Y.; Dou, X.; et al. Inhibition of STAT3 signaling contributes to the anti-melanoma effects of chrysoeriol. Phytomedicine 2023, 109, 154572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swoboda, A.; Soukup, R.; Eckel, O.; Kinslechner, K.; Wingelhofer, B.; Schorghofer, D.; Sternberg, C.; Pham, H.T.T.; Vallianou, M.; Horvath, J.; et al. STAT3 promotes melanoma metastasis by CEBP-induced repression of the MITF pathway. Oncogene 2021, 40, 1091–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; Liu, L.; Pei, H.; Zhang, J.; Chen, M.; Zhai, X. A LHFPL3-AS1/miR-580-3p/STAT3 Feedback Loop Promotes the Malignancy in Melanoma via Activation of JAK2/STAT3 Signaling. Mol. Cancer Res. 2020, 18, 1724–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ren, Z.; Xu, Y.; Gao, X.; Huang, H.; Zhu, F. KCNQ1OT1 sponges miR-34a to promote malignant progression of malignant melanoma via upregulation of the STAT3/PD-L1 axis. Environ. Toxicol. 2023, 38, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.L.; Nairismagi, M.L.; Laurensia, Y.; Lim, J.Q.; Tan, J.; Li, Z.M.; Pang, W.L.; Kizhakeyil, A.; Wijaya, G.C.; Huang, D.C.; et al. Oncogenic activation of the STAT3 pathway drives PD-L1 expression in natural killer/T-cell lymphoma. Blood 2018, 132, 1146–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerdes, I.; Wallerius, M.; Sifakis, E.G.; Wallmann, T.; Betts, S.; Bartish, M.; Tsesmetzis, N.; Tobin, N.P.; Coucoravas, C.; Bergh, J.; et al. STAT3 Activity Promotes Programmed-Death Ligand 1 Expression and Suppresses Immune Responses in Breast Cancer. Cancers 2019, 11, 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehexige, E.; Bao, M.; Bazarjav, P.; Yu, X.; Xiao, H.; Han, S.; Baigude, H. Silencing of STAT3 via Peptidomimetic LNP-Mediated Systemic Delivery of RNAi Downregulates PD-L1 and Inhibits Melanoma Growth. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Guo, A.; Liu, Z.; Xiang, S.; Zheng, F. Isoliquiritigenin attenuates tumor progression and PD-L1 expression by inhibiting the phosphorylation of STAT3 in melanoma. Med. Oncol. 2025, 42, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monti, M.; Benerini Gatta, L.; Bugatti, M.; Pezzali, I.; Picinoli, S.; Manfredi, M.; Lavazza, A.; Vanella, V.V.; De Giorgis, V.; Zanatta, L.; et al. Novel cellular systems unveil mucosal melanoma initiating cells and a role for PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in mucosal melanoma fitness. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Q.; Tian, S.; Zhou, H.; Mao, Y.; Li, X.; Yan, F.; Liu, A.; Hu, X.; You, C.; He, J. Salidroside inhibits melanin synthesis and melanoma growth via mTOR and PI3K/Akt pathways. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1583580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lou, N.; Zuo, M.; Zhu, F.; He, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Wang, X. STAT3-induced ZBED3-AS1 promotes the malignant phenotypes of melanoma cells by activating PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. RNA Biol. 2021, 18, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaoka, M.; Yanagaki, M.; Kubota, H.; Haruki, K.; Furukawa, K.; Taniai, T.; Onda, S.; Hamura, R.; Tsunematsu, M.; Shirai, Y.; et al. ARID4B Promotes the Progression of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Through the PI3K/AKT Pathway. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2025, 32, 3009–3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Liu, R.; Sun, X. STAT3-induced upregulation of lncRNA SNHG17 predicts a poor prognosis of melanoma and promotes cell proliferation and metastasis through regulating PI3K-AKT pathway. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 23, 8000–8010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Lin, X.; Zhang, L.; Hong, W.; Zhang, Y. Long noncoding RNA X-inactive specific transcript promotes malignant melanoma progression and oxaliplatin resistance. Melanoma Res. 2019, 29, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, Z.; Lin, W.; Yu, M. Downregulation of the expression of the lncRNA MIAT inhibits melanoma migration and invasion through the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Cancer Biomark. 2019, 24, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.N.; Fu, X.R.; Guo, H.; Fu, X.Y.; Shi, K.S.; Gao, T.; Yu, H.Q. YY1-induced lncRNA00511 promotes melanoma progression via the miR-150-5p/ADAM19 axis. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2024, 14, 809–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Tang, X.; Duan, S. Interference from LncRNA SPRY4-IT1 restrains the proliferation, migration, and invasion of melanoma cells through inactivating MAPK pathway by up-regulating miR-22-3p. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2019, 12, 477–487. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Zhang, L.; Jia, L.; Duan, Y.; Li, Y.; Bao, L.; Sha, N. Long non-coding RNA BANCR promotes proliferation in malignant melanoma by regulating MAPK pathway activation. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e100893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wang, J.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, S.; Le, Y.; He, R. Downregulation of BRAF-activated non-coding RNA suppresses the proliferation, migration and invasion, and induces apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 14, 4751–4757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flockhart, R.J.; Webster, D.E.; Qu, K.; Mascarenhas, N.; Kovalski, J.; Kretz, M.; Khavari, P.A. BRAFV600E remodels the melanocyte transcriptome and induces BANCR to regulate melanoma cell migration. Genome Res. 2012, 22, 1006–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samson, S.C.; Khan, A.M.; Mendoza, M.C. ERK signaling for cell migration and invasion. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 998475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Kuiatse, I.; Lee, A.V.; Pan, J.; Giuliano, A.; Cui, X. Sustained c-Jun-NH2-kinase activity promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition, invasion, and survival of breast cancer cells by regulating extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation. Mol. Cancer Res. 2010, 8, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saw, P.E.; Liu, Q.; Wong, P.P.; Song, E. Cancer stem cell mimicry for immune evasion and therapeutic resistance. Cell Stem Cell 2024, 31, 1101–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, X.; Zhang, D.; Lv, H.; Lei, X. LncRNA LHFPL3-AS1 Promotes Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Growth and Cisplatin Resistance Through Targeting miR-362-5p/CHSY1 Pathway. Onco Targets Ther. 2021, 14, 2293–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Gu, A.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Y.; Yu, Y.; Deng, X. Down-regulated long non-coding RNA LHFPL3 antisense RNA 1 inhibits the radiotherapy resistance of nasopharyngeal carcinoma via modulating microRNA-143-5p/homeobox A6 axis. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 5421–5433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shi, B.; Dong, F.; Zhu, X.; Liu, B.; Liu, Y. LncRNA KCNQ1OT1 facilitates the progression of bladder cancer by targeting MiR-218-5p/HS3ST3B1. Cancer Gene Ther. 2021, 28, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Sun, L.S.; Shen, H.M.; Qu, B. LncRNA KCNQ1OT1 accelerates ovarian cancer progression via miR-125b-5p/CD147 axis. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2022, 239, 154135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Chen, C.Y.; Hao, Y. LncRNA KCNQ1OT1 acts as miR-216b-5p sponge to promote colorectal cancer progression via up-regulating ZNF146. J. Mol. Histol. 2021, 52, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.L.; Chen, Y.L.; Chen, Q.H.; Tian, Q.; Yi, S.J. LncRNA KCNQ1OT1 promotes the metastasis of ovarian cancer by increasing the methylation of EIF2B5 promoter. Mol. Med. 2022, 28, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coe, E.A.; Tan, J.Y.; Shapiro, M.; Louphrasitthiphol, P.; Bassett, A.R.; Marques, A.C.; Goding, C.R.; Vance, K.W. The MITF-SOX10 regulated long non-coding RNA DIRC3 is a melanoma tumour suppressor. PLoS Genet. 2019, 15, e1008501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Xu, Z.; Jiang, J.; Gao, Y.; Gao, M.; Kang, J.; Wu, M.; Xiong, J.; et al. Long non-coding RNA GAS5 controls human embryonic stem cell self-renewal by maintaining NODAL signalling. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Yang, H.; Yi, Z.; Jiang, L.; Li, Y.; Han, Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, Z.; Kuang, Y.; et al. LncRNA GAS5 regulates redox balance and dysregulates the cell cycle and apoptosis in malignant melanoma cells. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 145, 637–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Yan, Z.; Hu, F.; Wei, W.; Yang, C.; Sun, Z. Long non-coding RNA GAS5 accelerates oxidative stress in melanoma cells by rescuing EZH2-mediated CDKN1C downregulation. Cancer Cell Int. 2020, 20, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Pan, T.; Jiang, D.; Jin, L.; Geng, Y.; Feng, X.; Shen, A.; Zhang, L. The lncRNA-GAS5/miR-221-3p/DKK2 Axis Modulates ABCB1-Mediated Adriamycin Resistance of Breast Cancer via the Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2020, 19, 1434–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, P.; Gao, X.; Wang, Y. Long noncoding RNA GAS5 suppresses triple negative breast cancer progression through inhibition of proliferation and invasion by competitively binding miR-196a-5p. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 104, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Lin, X.; Xu, P.; Jiao, Y.; Fu, P. LncRNA GAS5 sponges miR-362-5p to promote sensitivity of thyroid cancer cells to. IUBMB Life 2020, 72, 2420–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Li, M.; Miao, K.; Xu, H. lncRNA GAS5-promoted apoptosis in triple-negative breast cancer by targeting miR-378a-5p/SUFU signaling. J. Cell Biochem. 2020, 121, 2225–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.Q.; Wang, X.; Xue, B.H.; Zhao, Y.; Xie, F.; Wang, S.D.; Xue, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.S.; Qian, L.J. Chronic stress promotes glioma cell proliferation via the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Oncol. Rep. 2021, 46, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.J.; Xie, R.; Jiang, J.; Zhai, L.; Yang, C.H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Chen, D.X.; Niu, H.T.; Chen, L. 5-Aza-dC suppresses melanoma progression by inhibiting GAS5 hypermethylation. Oncol. Rep. 2022, 48, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasenson, S.E.; Alkalay, E.; Atrash, M.K.; Boocholez, A.; Gershbaum, J.; Hochberg-Laufer, H.; Shav-Tal, Y. The Association of MEG3 lncRNA with Nuclear Speckles in Living Cells. Cells 2022, 11, 1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, G.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, S. LncRNA MEG3 inhibits the proliferation and migration abilities of colorectal cancer cells by competitively suppressing MiR-31 and reducing the binding of MiR-31 to target gene SFRP1. Aging 2023, 16, 2061–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arega, S.; Dey, S.; Pani, S.; Dash, S.R.; Budhwar, R.; Kundu, C.N.; Ganguly, N. Determining the effect of long non-coding RNA maternally expressed gene 3 (lncRNA MEG3) on the transcriptome profile in cervical cancer cell lines. Genomics 2024, 116, 110957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Shi, S.; Wang, J.; Li, N. Long non-coding RNA MEG3 regulates migration and invasion of lung cancer stem cells via miR-650/SLC34A2 axis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 120, 109457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Guo, X.; Xia, J.; Shan, T.; Gu, C.; Liang, Z.; Zhao, W.; Jin, S. MiR-148a regulates MEG3 in gastric cancer by targeting DNA methyltransferase 1. Med. Oncol. 2014, 31, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Lou, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, S.; Lou, G. m(6)A methylation-mediated regulation of LncRNA MEG3 suppresses ovarian cancer progression through miR-885-5p and the VASH1 pathway. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Yan, X. lncRNA MEG3 Inhibits the Proliferation and Growth of Glioma Cells by Downregulating Bcl-xL in the PI3K/Akt/NF-. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 3729069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, D.; Wang, Z.; Yang, H.; Wang, R.; Shi, X.; Liu, Z.; Xu, F.; Lu, Q.; Chu, X.; Sang, J. Long non-coding RNA MEG3 acts as a suppressor in breast cancer by regulating miR-330/CNN1. Aging 2024, 16, 1318–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Wu, X.; Huang, L.; Long, C.; Lu, Q.; Huang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Li, W.; Pu, J. LncRNA MEG3 Reduces the Ratio of M2/M1 Macrophages Through the HuR/CCL5 Axis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Hepatocell. Carcinoma 2024, 11, 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhang, W.; Pu, F.; Zhang, Z. LncRNA MEG3 promotes chemosensitivity of osteosarcoma by regulating antitumor immunity via miR-21-5p/p53 pathway and autophagy. Genes. Dis. 2023, 10, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, J.; Zhang, S. Long non-coding RNA MEG-3 suppresses gastric carcinoma cell growth, invasion and migration via EMT regulation. Mol. Med. Rep. 2019, 20, 2685–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Jin, L.; He, J.; Wang, R.; Wang, Y.; Bai, J.; Chen, Y.; Luo, Z. Upregulation LncRNA MEG3 expression suppresses proliferation and metastasis in melanoma via miR-208/SOX4. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2023, 478, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhuang, Y.; Fu, X.; Li, C. LncRNA POU3F3 promotes melanoma cell proliferation by downregulating lncRNA MEG3. Discov. Oncol. 2021, 12, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, X.; Feng, H.; He, S.; Chen, X.; Chen, M.; Hu, X. HGF facilitates methylation of MEG3, potentially implicated in vemurafenib resistance in melanoma. J. Gene Med. 2024, 26, e3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Lin, J.; Li, C.; Xu, T.; Chen, C.; Lan, B.; Wang, X.; Bai, S.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, H.; et al. MET amplification correlates with poor prognosis and immunotherapy response as a subtype of melanoma: A multicenter retrospective study. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhu, L.; Li, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Lin, X.; Yang, C. LncRNA MEG3 promotes melanoma growth, metastasis and formation through modulating miR-21/E-cadherin axis. Cancer Cell Int. 2020, 20, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Backer, J.; Lin, A.; Berghe, W.V.; Bogaerts, A.; Hoogewijs, D. Cytoglobin inhibits non-thermal plasma-induced apoptosis in melanoma cells through regulation of the NRF2-mediated antioxidant response. Redox Biol. 2022, 55, 102399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Tu, Y.; Liu, C.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, M.; Li, Q. Gambogenic Acid Inhibits Invasion and Metastasis of Melanoma through Regulation of lncRNA MEG3. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2023, 46, 1385–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stansel, T.; Wickline, S.A.; Pan, H. NF-kappaB Inhibition Suppresses Experimental Melanoma Lung Metastasis. J. Cancer Sci. Clin. Ther. 2020, 4, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janostiak, R.; Rauniyar, N.; Lam, T.T.; Ou, J.; Zhu, L.J.; Green, M.R.; Wajapeyee, N. MELK Promotes Melanoma Growth by Stimulating the NF-kappaB Pathway. Cell Rep. 2017, 21, 2829–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, D.; Gao, C.; Bao, K.; Song, G. The long non-coding RNA NKILA inhibits the invasion-metastasis cascade of malignant melanoma via the regulation of NF-kB. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2017, 7, 28–40. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Rao, Y.; Sun, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Bu, W. Long noncoding RNA CPS1-IT1 suppresses melanoma cell metastasis through inhibiting Cyr61 via competitively binding to BRG1. J. Cell Physiol. 2019, 234, 22017–22027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.; Kim, K.D.; Park, S.Q.; Kim, D.S.; Choi, Y.S.; Nam, H.S.; Lee, S.H.; Cho, M.K. CYR61 Is Overexpressed in Human Melanoma Tissue Ex Vivo and Promotes Melanoma Cell Survival and Proliferation Through Its Binding Ligand Integrin beta3 In Vitro. Ann. Dermatol. 2024, 36, 392–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, X.; Mou, K.H.; Ge, R.; Han, D.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, L.J. Linc00961 inhibits the proliferation and invasion of skin melanoma by targeting the miR-367/PTEN axis. Int. J. Oncol. 2019, 55, 708–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xu, W.; Zheng, Z.; Cao, Z. LINC00459 sponging miR-218 to elevate DKK3 inhibits proliferation and invasion in melanoma. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, C.; Tan, S. LncRNA FENDRR Suppresses Melanoma Growth via Influencing c-Myc mRNA Level. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2023, 16, 2119–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Fang, J.; Xiao, Z.; Deng, J.; Zhang, M.; Gu, L. Downregulation of lncRNA TSLNC8 promotes melanoma resistance to BRAF inhibitor PLX4720 through binding with PP1alpha to re-activate MAPK signaling. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 147, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, A.; Cao, M.; Li, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Fang, F.; Zhao, L.; Wang, Q.; Lin, T.; Wang, Y. Lnc-PKNOX1-1 inhibits tumor progression in cutaneous malignant melanoma by regulating NF-kappaB/IL-8 axis. Carcinogenesis 2023, 44, 871–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Jin, M.; Mu, Z.; Li, Z.; Qi, R.; Han, X.; Jiang, H. Inhibiting melanoma tumor growth: The role of oxidative stress-associated LINC02132 and COPDA1 long non-coding RNAs. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1558292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, B.; Zheng, Y.; Ma, S.; Xing, Q.; Wang, X.; Yang, B.; Yin, G.; Guan, F. BANCR contributes to the growth and invasion of melanoma by functioning as a competing endogenous RNA to upregulate Notch2 expression by sponging miR-204. Int. J. Oncol. 2017, 51, 1941–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Han, H.; Li, P.; Wei, W.; Lin, N. lncRNA NEAT1 facilitates melanoma cell proliferation, migration, and invasion via regulating miR-495-3p and E2F3. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 19592–19601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Lv, W. MiR-363 restrain the proliferation, migration and invasion of colorectal carcinoma cell by targeting E2F3. J. Cancer 2023, 14, 1362–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Wang, S.; Qin, T.; Wang, W. Circular RNA (circ-0075804) promotes the proliferation of retinoblastoma via combining heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K (HNRNPK) to improve the stability of E2F transcription factor 3 E2F3. J. Cell Biochem. 2020, 121, 3516–3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zeng, K.; Liu, Y.; Gao, L.; Liu, L. LncRNA SNHG5 promotes growth and invasion in melanoma by regulating the miR-26a-5p/TRPC3 pathway. OncoTargets Ther. 2018, 12, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, D.C.; Zheng, S.Y.; Zhang, Z.G.; Luo, J.H.; Zhu, Z.L.; Li, L.; Chen, L.S.; Lin, X.; Sham, J.S.K.; Lin, M.J.; et al. TRPC3 promotes tumorigenesis of gastric cancer via the CNB2/GSK3beta/NFATc2 signaling pathway. Cancer Lett. 2021, 519, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, L.; Zheng, Y.; Wen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, W. Increased expression of long noncoding RNA GAS6-AS2 promotes proliferation and inhibits apoptosis of melanoma cells via upregulating GAS6 expression. IUBMB Life 2019, 71, 1503–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Hu, L.; Fu, G.; Lu, J.; Zheng, Y.; Li, Y.; Jia, L. LncRNA MALAT1 Promotes the Proliferation, Migration, and Invasion of Melanoma Cells by Downregulating miR-23a. Cancer Manag. Res. 2020, 12, 6553–6562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mou, K.; Liu, B.; Ding, M.; Mu, X.; Han, D.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, L.-J. lncRNA-ATB functions as a competing endogenous RNA to promote YAP1 by sponging miR-590-5p in malignant melanoma. Int. J. Oncol. 2018, 53, 1094–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Gao, Y.; Niu, X.; Tang, M.; Li, J.; Song, B.; Guan, X. LncRNA BASP1-AS1 interacts with YBX1 to regulate Notch transcription and drives the malignancy of melanoma. Cancer Sci. 2021, 112, 4526–4542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, G.; Wang, D.; Mei, Y. TRMP, a p53-inducible long noncoding RNA, regulates G1/S cell cycle progression by modulating IRES-dependent p27 translation. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, T.; Khan, M.R.; Zhang, X.D.; Li, J.; Thorne, R.F.; Wu, M.; Shao, F. lncRNA TRMP-S directs dual mechanisms to regulate p27-mediated cellular senescence. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2021, 24, 971–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Dang, P.; Liu, Y.; Qiao, B.; Sun, Z. Noncoding RNAs in pyroptosis and cancer progression: Effect, mechanism, and clinical application. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 982040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.n.; Wang, Z.; Houssou Hounye, A.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Qi, M. A novel pyroptosis-related LncRNA signature predicts prognosis and indicates tumor immune microenvironment in skin cutaneous melanoma. Life Sci. 2022, 307, 120832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Dian, Y.; Zeng, F.; Deng, G.; Chen, X. Ferroptosis: A Targetable Vulnerability for Melanoma Treatment. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2025, 145, 1323–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, D.; Saha, P.; Samanta, A.; Bishayee, A. Emerging Concepts of Hybrid Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Cancer Progression. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, L.; Wei, R. Long Non-Coding RNA-CASC15 Promotes Cell Proliferation, Migration, and Invasion by Activating Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway in Melanoma. Pathobiology 2019, 87, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cong, L.; Zhao, Q.; Sun, H.; Zhou, Z.; Hu, Y.; Li, C.; Hao, M.; Cong, X. A novel long non-coding RNA SLNCR1 promotes proliferation, migration, and invasion of melanoma via transcriptionally regulating SOX5. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Wang, M.; Liu, X.; Chen, X.; Cheng, H.; Wang, G. LncRNA NEAT1 antagonizes the inhibition of melanoma proliferation, migration, invasion and EMT by Polyphyllin B. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2023, 396, 2469–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, A.; Prekeris, R. The regulation of MMP targeting to invadopodia during cancer metastasis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2015, 3, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yang, H.; Xiao, Y.; Tang, X.; Li, Y.; Han, Q.; Fu, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, Y. Lentiviral-mediated overexpression of long non-coding RNA GAS5 reduces invasion by mediating MMP2 expression and activity in human melanoma cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2016, 48, 1509–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Lu, J.; Chen, L.; Zhang, S.; Qi, W.; Li, W.; Xu, H. Long noncoding RNA TTN-AS1 facilitates tumorigenesis and metastasis by maintaining TTN expression in skin cutaneous melanoma. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; He, D.; Xiao, M.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Cao, K. Long noncoding RNA LINC00518 induces radioresistance by regulating glycolysis through an miR-33a-3p/HIF-1α negative feedback loop in melanoma. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, E.; Hou, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, J.; Li, M. Effects of natural products on angiogenesis in melanoma. Fitoterapia 2024, 177, 106100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, W.C.; Jour, G.; Aung, P.P. Role of angiogenesis in melanoma progression: Update on key angiogenic mechanisms and other associated components. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2019, 59, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedipour, F.; Zamani, P.; Jamialahmadi, K.; Jaafari, M.R.; Sahebkar, A. Vaccines targeting angiogenesis in melanoma. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 912, 174565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, K.; Koon, H.; Elson, P.; Triozzi, P.; Dowlati, A.; Chen, H.; Borden, E.C.; Rini, B.I. Dual VEGF/VEGFR inhibition in advanced solid malignancies: Clinical effects and pharmacodynamic biomarkers. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2014, 15, 975–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bannoud, N.; Stupirski, J.C.; Cagnoni, A.J.; Hockl, P.F.; Pérez Sáez, J.M.; García, P.A.; Mahmoud, Y.D.; Gambarte Tudela, J.; Scheidegger, M.A.; Marshall, A.; et al. Circulating galectin-1 delineates response to bevacizumab in melanoma patients and reprograms endothelial cell biology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2214350120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felcht, M.; Thomas, M. Angiogenesis in malignant melanoma. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2015, 13, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandita, A.; Ekstrand, M.; Bjursten, S.; Zhao, Z.; Fogelstrand, P.; Le Gal, K.; Ny, L.; Bergo, M.O.; Karlsson, J.; Nilsson, J.A.; et al. Intussusceptive Angiogenesis in Human Metastatic Malignant Melanoma. Am. J. Pathol. 2021, 191, 2023–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, B.; Biswas, S.; Wrigley, J.; Sirohi, B.; Corrie, P. Angiogenesis in cutaneous malignant melanoma and potential therapeutic strategies. Expert. Rev. Anticancer. Ther. 2009, 9, 1583–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekan, M.; Ebrahimzadeh, M.A.; Sheida, F. The role of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1alpha and its signaling in melanoma. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 141, 111873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Luo, Y.; He, Y.; Li, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Hou, J.; Zhou, S. In-situ-sprayed therapeutic hydrogel for oxygen-actuated Janus regulation of postsurgical tumor recurrence/metastasis and wound healing. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüser, L.; Chhabra, Y.; Gololobova, O.; Wang, V.; Liu, G.; Dixit, A.; Rocha, M.R.; Harper, E.I.; Fane, M.E.; Marino-Bravante, G.E.; et al. Aged fibroblast-derived extracellular vesicles promote angiogenesis in melanoma. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 114721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, H.J.; Oh, H.A.; Nam, S.Y.; Han, N.R.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, M.H.; Moon, P.D.; Kim, H.M. The critical role of mast cell-derived hypoxia-inducible factor-1α in human and mice melanoma growth. Int. J. Cancer 2013, 132, 2492–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marneros, A.G. Tumor angiogenesis in melanoma. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North. Am. 2009, 23, 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodi, F.S.; Lawrence, D.; Lezcano, C.; Wu, X.; Zhou, J.; Sasada, T.; Zeng, W.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Atkins, M.B.; Ibrahim, N.; et al. Bevacizumab plus ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2014, 2, 632–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Babapoor-Farrokhran, S.; Rodrigues, M.; Deshpande, M.; Puchner, B.; Kashiwabuchi, F.; Hassan, S.J.; Asnaghi, L.; Handa, J.T.; Merbs, S.; et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 upregulation of both VEGF and ANGPTL4 is required to promote the angiogenic phenotype in uveal melanoma. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 7816–7828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Xia, Y.; Chen, W.; Dong, H.; Cui, B.; Liu, C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, F.; Du, J. Regulation and Therapeutic Application of Long non-Coding RNA in Tumor Angiogenesis. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2024, 23, 15330338241273239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Hu, X.; Xin, W.; Wang, X. Exosomal Non-coding RNAs: A New Approach to Melanoma Diagnosis and Therapeutic Strategy. Curr. Med. Chem. 2024, 31, 6084–6109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, M.; Babakhanzadeh, E.; Mollazadeh, A.; Ahmadzade, M.; Mohammadi Soleimani, E.; Hajimaqsoudi, E. HOTAIR in cancer: Diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic perspectives. Cancer Cell Int. 2024, 24, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Chen, H.; Zuo, L.; Jiang, H.; Yan, H. Suppression of long noncoding RNA MALAT1 inhibits the development of uveal melanoma via microRNA-608-mediated inhibition of HOXC4. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2020, 318, C903–C912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Zhu, X.; Xue, K.; Huang, Y.; Wu, M.; Yang, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, H.; He, L.; Sun, H. LncRNA DANCR Enhances Angiogenesis to Promote Melanoma Progression Via Sponging miR-5194. J. Cancer 2023, 14, 1161–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Li, X.; Zhao, H.; Liu, H. Long non-coding RNAs: Potential new biomarkers for predicting tumor invasion and metastasis. Mol. Cancer 2016, 15, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vimalraj, S.; Subramanian, R.; Dhanasekaran, A. LncRNA MALAT1 Promotes Tumor Angiogenesis by Regulating MicroRNA-150-5p/VEGFA Signaling in Osteosarcoma. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 742789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leucci, E.; Vendramin, R.; Spinazzi, M.; Laurette, P.; Fiers, M.; Wouters, J.; Radaelli, E.; Eyckerman, S.; Leonelli, C.; Vanderheyden, K.; et al. Melanoma addiction to the long non-coding RNA SAMMSON. Nature 2016, 531, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Zheng, H.; Tse, G.; Chan, M.T.; Wu, W.K. Long non-coding RNAs in melanoma. Cell Prolif. 2018, 51, e12457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhai, M.; Micheroli, R.; Houtman, M.; Mirrahimi, M.; Moser, L.; Pauli, C.; Burki, K.; Laimbacher, A.; Kania, G.; Klein, K.; et al. The long non-coding RNA HOTAIR contributes to joint-specific gene expression in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 8172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, D.; Leung, E.Y.; Baguley, B.C.; Finlay, G.J.; Askarian-Amiri, M.E. Epigenetic regulation in human melanoma: Past and future. Epigenetics 2015, 10, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.; Yan, Y.; Ren, Y.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhi, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Shao, Y.; Liu, J. LncRNA SAMMSON Mediates Adaptive Resistance to RAF Inhibition in BRAF-Mutant Melanoma Cells. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 2918–2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewaele, S.; Delhaye, L.; De Paepe, B.; de Bony, E.J.; De Wilde, J.; Vanderheyden, K.; Anckaert, J.; Yigit, N.; Nuytens, J.; Vanden Eynde, E.; et al. The long non-coding RNA SAMMSON is essential for uveal melanoma cell survival. Oncogene 2022, 41, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemian, M.; Babaahmadi-Rezaei, H.; Khedri, A.; Selvaraj, C. The oncogenic role of SAMMSON lncRNA in tumorigenesis: A comprehensive review with especial focus on melanoma. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2023, 27, 3966–3973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goding, C.R. Targeting the lncRNA SAMMSON Reveals Metabolic Vulnerability in Melanoma. Cancer Cell 2016, 29, 619–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beatriz Cristina Biz, T.; Carolina de Sousa, C.S.; Frank John, S.; Miriam Galvonas, J. LncRNAs in melanoma phenotypic plasticity: Emerging targets for promising therapies. RNA Biol. 2024, 21, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, Y.; Kumar, S.M.; Xu, X. Molecular pathogenesis of sporadic melanoma and melanoma-initiating cells. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2010, 134, 1740–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diazzi, S.; Tartare-Deckert, S.; Deckert, M. The mechanical phenotypic plasticity of melanoma cell: An emerging driver of therapy cross-resistance. Oncogenesis 2023, 12, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hölzel, M.; Tüting, T. Inflammation-Induced Plasticity in Melanoma Therapy and Metastasis. Trends Immunol. 2016, 37, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roesch, A. Melanoma stem cells. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2015, 13, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villani, V.; Sabbatino, F.; Ferrone, C.R.; Ferrone, S. Melanoma initiating cells: Where do we stand? Melanoma Manag. 2015, 2, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.Y.; Lin, Y.; Lee, J.H.; Pedersen, B.; Stewart, A.; Scolyer, R.A.; Long, G.V.; Yang, J.Y.H.; Rizos, H. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals melanoma cell state-dependent heterogeneity of response to MAPK inhibitors. EBioMedicine 2024, 107, 105308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliuca, C.; Di Leo, L.; De Zio, D. New Insights into the Phenotype Switching of Melanoma. Cancers 2022, 14, 6118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballotti, R. Identification of melanoma initiating cells: Does CD271 have a future? Future Oncol. 2015, 11, 1587–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, G.F.; Wilson, B.J.; Girouard, S.D.; Frank, N.Y.; Frank, M.H. Stem cells and targeted approaches to melanoma cure. Mol. Aspects Med. 2014, 39, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utikal, J.; Maherali, N.; Kulalert, W.; Hochedlinger, K. Sox2 is dispensable for the reprogramming of melanocytes and melanoma cells into induced pluripotent stem cells. J. Cell Sci. 2009, 122, 3502–3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.; Pillai, M.; Duddu, A.S.; Somarelli, J.A.; Goyal, Y.; Jolly, M.K. Dynamical hallmarks of cancer: Phenotypic switching in melanoma and epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2023, 96, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simiczyjew, A.; Kot, M.; Majkowski, M.; Zietek, M.; Matkowski, R.; Nowak, D. Phenotype switching in highly invasive resistant to vemurafenib and cobimetinib melanoma cells. Cell Commun. Signal 2025, 23, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capparelli, C.; Purwin, T.J.; Glasheen, M.; Caksa, S.; Tiago, M.; Wilski, N.; Pomante, D.; Rosenbaum, S.; Nguyen, M.Q.; Cai, W.; et al. Targeting SOX10-deficient cells to reduce the dormant-invasive phenotype state in melanoma. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, K.D.; Tiwari, S.; Thier, B.; Qiu, L.C.; Lin, T.C.; Paschen, A.; Imig, J. Long non-coding RNA GRASLND links melanoma differentiation and interferon-gamma response. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2024, 11, 1471100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.Y.; Ahmed, Y.K.; Mohammed, S.; Alghamdi, M.A.; Al-Ghamdi, H.S.; Mohammed, J.S.; Jawad, M.A.; Alsaadi, S.B. Metabolism at the core of melanoma: From bioenergetics to immune escape and beyond. Semin. Oncol. 2025, 52, 152413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gui, Q.; Luo, W.; Wu, D.; Liu, J.; Zhou, D.; Zhu, X.; Wu, M.; Zhu, L. Construction and validation of a lipid metabolism-related genes prognostic signature for skin cutaneous melanoma. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2025, 775, 152115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SAMMSON Long Noncoding RNA Is Essential for Melanoma Cell Viability. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 470. [CrossRef]

- van der Bliek, A.M.; Sedensky, M.M.; Morgan, P.G. Cell Biology of the Mitochondrion. Genetics 2017, 207, 843–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Hartman, C.L.; Li, L.; Albert, C.J.; Si, F.; Gao, A.; Huang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Lin, W.; Hsueh, E.C.; et al. Reprogramming lipid metabolism prevents effector T cell senescence and enhances tumor immunotherapy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eaaz6314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tao, Y.; Zhao, L.; Abusalamah, H.; Huffman, C.; Harbison, R.A.; Puram, S.V.; Wang, Y.; et al. Tumor extracellular vesicle-derived PD-L1 promotes T cell senescence through lipid metabolism reprogramming. Sci. Transl. Med. 2025, 17, eadm7269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Cai, F.; Dahabieh, M.S.; Gunawardena, K.; Talebi, A.; Dehairs, J.; El-Turk, F.; Park, J.Y.; Li, M.; Goncalves, C.; et al. Peroxisome disruption alters lipid metabolism and potentiates antitumor response with MAPK-targeted therapy in melanoma. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 133, e166644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewaele, S.; Delhaye, L.; De Paepe, B.; Bogaert, B.; Martinez, R.; Anckaert, J.; Yigit, N.; Nuytens, J.; Van Coster, R.; Eyckerman, S.; et al. mTOR Inhibition Enhances Delivery and Activity of Antisense Oligonucleotides in Uveal Melanoma Cells. Nucleic Acid. Ther. 2023, 33, 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariano, C.; Costanza, F.; Akman, M.; Riganti, C.; Corà, D.; Casanova, E.; Astanina, E.; Comunanza, V.; Bussolino, F.; Doronzo, G. TFEB inhibition induces melanoma shut-down by blocking the cell cycle and rewiring metabolism. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Liu, W.; Liu, W.; Wang, C. Diagnostic and prognostic significance of long noncoding RNA LINC00173 in patients with melanoma. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. (1992) 2022, 68, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masrour, M.; Khanmohammadi, S.; Fallahtafti, P.; Hashemi, S.M.; Rezaei, N. Long non-coding RNA as a potential diagnostic and prognostic biomarker in melanoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2024, 28, e18109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Li, J.; Chen, W.; Wang, Z.; Wang, D.; Liu, C.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, C.; Chang, Y.; et al. NetLnc: A Network-Based Computational Framework to Identify Immune Checkpoint-Related lncRNAs for Immunotherapy Response in Melanoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, J.; Onieva, J.L.; Garrido-Barros, M.; Berciano-Guerrero, M.A.; Sanchez-Munoz, A.; Jose Lozano, M.; Farngren, A.; Alvarez, M.; Martinez-Galvez, B.; Perez-Ruiz, E.; et al. Association of Circular RNA and Long Non-Coding RNA Dysregulation with the Clinical Response to Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Cutaneous Metastatic Melanoma. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, M.C.; Sethuraman, S.N.; Singh, M.P.; Malayer, J.; Ranjan, A. LncRNA FENDRR Expression Correlates with Tumor Immunogenicity. Genes 2021, 12, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toker, J.; Iorgulescu, J.B.; Ling, A.L.; Villa, G.R.; Gadet, J.; Parida, L.; Getz, G.; Wu, C.J.; Reardon, D.A.; Chiocca, E.A.; et al. Clinical Importance of the lncRNA NEAT1 in Cancer Patients Treated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 2226–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cinque, S.; Verheyden, Y.; Adnane, S.; Marino, A.; Hanache, S.; Vendramin, R.; Cuomo, A.; Pozniak, J.; Cortes Calabuig, A.; Baldewijns, M.; et al. The assembly of cancer-specific ribosomes by the lncRNA LISRR suppresses melanoma anti-tumor immunity. J. Exp. Med. 2026, 223, e20251507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, J.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Mao, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Pian, C. NcPath: A novel platform for visualization and enrichment analysis of human non-coding RNA and KEGG signaling pathways. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btac812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, W.; Li, R.; Liu, L.; Ni, X.; Shi, Y.; Xia, Y.; Wang, J.; Lu, F.; Xu, B. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR acts as a competing endogenous RNA to promote malignant melanoma progression by sponging miR-152-3p. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 85401–85414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| LncRNA | Expression | Action | Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BANCR | up | microRNA-204 down-regulator (Notch2 pathway) | Promotion of EMT and tumorigenesis | [94] |

| NEAT1 | up | miR-495-3p inhibitor and E2F3 inductor | Promotion of EMT and tumorigenesis | [95,112] |

| SNHG5 | up | miR-26a-5p inhibitor | Biomarker of advanced stage of melanoma | [98] |

| SPRY4-IT1 | up | miR-22-3p up-regulator | Melanoma cell proliferation, invasion, migration, and EMT stimulator | [42] |

| GAS6-AS2 | up | GAS6 expression up-regulator | Melanoma cell proliferation stimulator, biomarker of advanced stage and poor prognosis | [100] |

| MALAT1 | up | CyclinD1 and CyclinE1 expression stimulator | Melanoma cell proliferation stimulator; apoptosis inhibitor | [17,101] |

| FOXC2-AS1 | up | silencing p15 | Melanoma cell proliferation stimulator; marker of poor prognosis | [9] |

| lncRNA-ATB | up | miR-590-5p sponge | Melanoma cell proliferation, invasion, and migration stimulator | [102] |

| XIST | up | miR-21 sponge | [39] | |

| BASP1-AS1 | up | Notch pathway activator | Oncogene expression stimulator | [103] |

| MIAT | up | PI3K/AKT pathway activator c-MYC and cyclin D1 expression stimulator | [40] | |

| lncRNA-TTN-AS1 | up | Cyclin D1, CDK2, and CDK4 up-regulator; titin expression stimulator | Apoptosis inhibitor; marker of poor prognosis; EMT stimulator | [115] |

| FENDRR | down | Cyclin E1, Cyclin D1, CDK4, and CDK6 down-regulator | Melanoma cell growth suppressor | [90] |

| TRMP | up | p27 inhibitor | Metastasis promotor | [104] |

| TRMP-S | up | p27 inhibitor | Melanoma cell proliferation stimulator, cell senescence suppressor | [105] |

| LINC-PINT | down | Recruits EZH2, leading to H3K27 trimethylation | Tumorigenesis and cell migration suppressor | [10] |

| GAS5 | down | Bcl-2 expression stimulator | Melanoma cell apoptosis | [57,114] |

| LHFPL3-AS1 | up | Bcl-2 degradation inhibitor | Apoptosis suppressor | [20] |

| CASC15 | Wnt/β-catenin pathway activator | Melanoma cell proliferation and EMT stimulator | [110] | |

| SLNCR1 | up | SLNCR1/SOX5 axis | EMT stimulator | [111] |

| lncRNA | Mechanism | Effect | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| MALAT1 | Sponges miR-140/miR-145/miR-497 → ↑ VEGF-A, FGF2; stabilises HIF-1α; activates VEGFR2 | Strong promotion of angiogenesis and vessel maturation | [135,138,140] |

| HOTAIR | Recruits EZH2/PRC2 → epigenetic silencing of PTEN, P21 → ↑ PI3K/AKT → ↑ HIF-1α/VEGF | Increased VEGF secretion even under normoxia | [134,140,141,142] |

| BANCR | Activates NF-κB → ↑ VEGF-C and VEGFR-3 | Strongly promotes lymphangiogenesis and nodal metastasis | [140,142] |

| SLNCR1 | Scaffolds AR/Brn3a at MMP9 promoter + recruits DNMT1 to silence SPRY2 | Enhances invasion and angiogenesis | [12,140] |

| DANCR | ceRNA for miR-5194 → derepresses multiple pro-angiogenic targets | Increased tube formation and endothelial recruitment | [136] |

| SAMMSON | Interacts with p32/CARF in mitochondria → maintains OXPHOS under hypoxia → ↑ VEGF | Hypoxia-driven angiogenesis; high vessel density in PDX models | [139,140,143,144,145,146] |

| CPS1-IT1 | Inhibits Cyr61, VEGF, MMP-9 expression; blocks ERK signalling | Strong suppression of angiogenesis and EMT | [86] |

| NKILA | Directly binds and inhibits IκB phosphorylation → blocks NF-κB → ↓ IL-8/VEGF | Reduced inflammatory cytokine-driven angiogenesis | [85] |

| MEG3 | Stabilises p53 → ↓ VEGF; competes with miR-183 for binding | Decreased angiogenesis and tumour growth | [140,142] |

| GAS5 | Sponges miR-210 → inhibits HIF-1α stabilisation under hypoxia | Reduced VEGF secretion and vessel formation | [140,142] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kiełbowski, K.; Ćmil, M.; Dach, A.; Cole, A.; Jerzyńska, O.; Bakinowska, E.; Plewa, P.; Pawlik, A. Silent Players, Loud Impact: The Influence of lncRNAs on Melanoma Progression. Cancers 2025, 17, 4033. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17244033

Kiełbowski K, Ćmil M, Dach A, Cole A, Jerzyńska O, Bakinowska E, Plewa P, Pawlik A. Silent Players, Loud Impact: The Influence of lncRNAs on Melanoma Progression. Cancers. 2025; 17(24):4033. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17244033

Chicago/Turabian StyleKiełbowski, Kajetan, Maciej Ćmil, Aleksandra Dach, Aleksandra Cole, Oliwia Jerzyńska, Estera Bakinowska, Paulina Plewa, and Andrzej Pawlik. 2025. "Silent Players, Loud Impact: The Influence of lncRNAs on Melanoma Progression" Cancers 17, no. 24: 4033. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17244033

APA StyleKiełbowski, K., Ćmil, M., Dach, A., Cole, A., Jerzyńska, O., Bakinowska, E., Plewa, P., & Pawlik, A. (2025). Silent Players, Loud Impact: The Influence of lncRNAs on Melanoma Progression. Cancers, 17(24), 4033. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17244033