Secondary Genetic Events and Their Relationship to TP53 Mutation in Mantle Cell Lymphoma: A Sub-Study from the FIL_MANTLE-FIRST BIO on Behalf of Fondazione Italiana Linfomi (FIL)

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

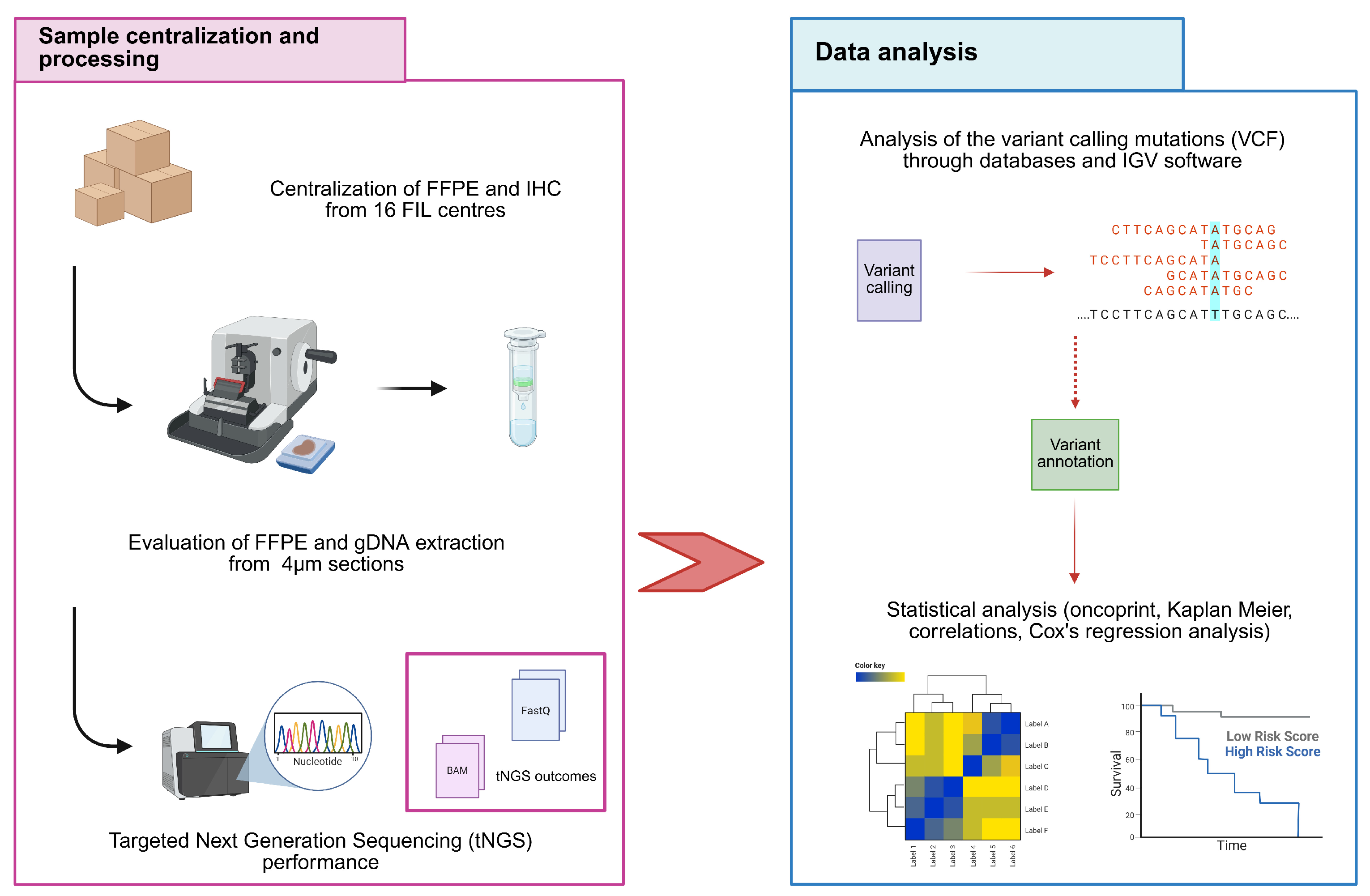

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Inclusion Criteria

2.2. Extraction and Quality Control of Genomic DNA (gDNA)

2.3. Targeted Next Generation Sequencing (tNGS)

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Features of the Analyzed Cohort

3.2. Copy Number Variations (CNVs) Identification and Description

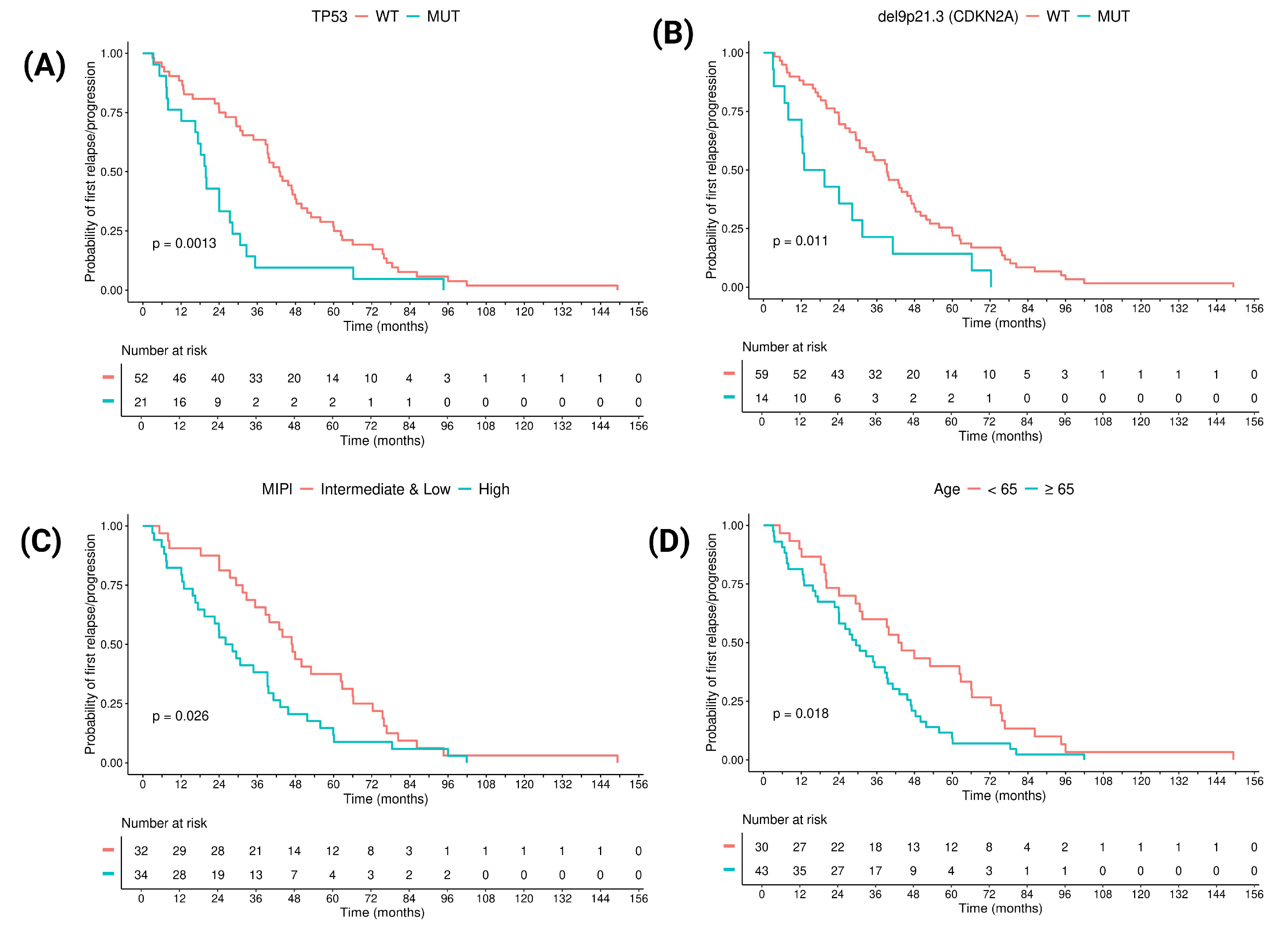

3.3. Prognostic Factors in Terms of Time to POD: Clinical and Molecular Features

3.4. Identification of Molecular Clusters That Provide Risk Stratification

3.5. TP53 Mutation and Its Interaction with the Clustering Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kumar, A.; Eyre, T.A.; Lewis, K.L.; Thompson, M.C.; Cheah, C.Y. New Directions for Mantle Cell Lymphoma in 2022. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2022, 42, 614–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomben, R.; Ferrero, S.; D’Agaro, T.; Dal Bo, M.; Re, A.; Evangelista, A.; Carella, A.M.; Zamò, A.; Vitolo, U.; Omedè, P.; et al. A B-cell receptor-related gene signature predicts survival in mantle cell lymphoma: Results from the Fondazione Italiana Linfomi MCL-0208 trial. Haematologica 2018, 103, 849–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreyling, M.; Klapper, W.; Rule, S. Blastoid and pleomorphic mantle cell lymphoma: Still a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge! Blood 2018, 132, 2722–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streich, L.; Sukhanova, M.; Lu, X.; Chen, Y.; Venkataraman, G.; Mathews, S.; Zhang, S.; Kelemen, K.; Segal, J.; Gao, J.; et al. Aggressive morphologic variants of mantle cell lymphoma characterized with high genomic instability showing frequent chromothripsis, CDKN2A/B loss, and TP53 mutations: A multi-institutional study. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2020, 59, 484–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoster, E.; Dreyling, M.; Klapper, W.; Gisselbrecht, C.; van Hoof, A.; Kluin-Nelemans, H.C.; Pfreundschuh, M.; Reiser, M.; Metzner, B.; Einsele, H.; et al. A new prognostic index (MIPI) for patients with advanced-stage mantle cell lymphoma. Blood 2008, 111, 558–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoster, E.; Rosenwald, A.; Berger, F.; Bernd, H.-W.; Hartmann, S.; Loddenkemper, C.; Barth, T.F.; Brousse, N.; Pileri, S.; Rymkiewicz, G.; et al. Prognostic Value of Ki-67 Index, Cytology, and Growth Pattern in Mantle-Cell Lymphoma: Results From Randomized Trials of the European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Network. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 1386–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Bai, O. Function and regulation of lipid signaling in lymphomagenesis: A novel target in cancer research and therapy. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2020, 154, 103071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakhdari, A.; Ok, C.Y.; Patel, K.P.; Kanagal-Shamanna, R.; Yin, C.C.; Zuo, Z.; Hu, S.; Routbort, M.J.; Luthra, R.; Medeiros, L.J.; et al. TP53 mutations are common in mantle cell lymphoma, including the indolent leukemic non-nodal variant. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 2019, 41, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarian, G.; Chemali, L.; Bensalah, M.; Zindel, C.; Lefebvre, V.; Thieblemont, C.; Martin, A.; Tueur, G.; Letestu, R.; Fleury, C.; et al. TP53 Mutations Detected by NGS Are a Major Clinical Risk Factor for Stratifying Mantle Cell Lymphoma. Am. J. Hematol. 2025, 100, 933–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrero, S.; Ragaini, S. Advancing Mantle Cell Lymphoma Risk Assessment: Navigating a Moving Target. Hematol. Oncol. 2025, 43, e70072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visco, C.; Di Rocco, A.; Evangelista, A.; Quaglia, F.M.; Tisi, M.C.; Morello, L.; Zilioli, V.R.; Rusconi, C.; Hohaus, S.; Sciarra, R.; et al. Outcomes in first relapsed-refractory younger patients with mantle cell lymphoma: Results from the MANTLE-FIRST study. Leukemia 2021, 35, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karolová, J.; Kazantsev, D.; Svatoň, M.; Tušková, L.; Forsterová, K.; Maláriková, D.; Benešová, K.; Heizer, T.; Dolníková, A.; Klánová, M.; et al. Sequencing-based analysis of clonal evolution of 25 mantle cell lymphoma patients at diagnosis and after failure of standard immunochemotherapy. Am. J. Hematol. 2023, 98, 1627–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khouja, M.; Jiang, L.; Pal, K.; Stewart, P.J.; Regmi, B.; Schwarz, M.; Klapper, W.; Alig, S.K.; Darzentas, N.; Kluin-Nelemans, H.C.; et al. Comprehensive genetic analysis by targeted sequencing identifies risk factors and predicts patient outcome in Mantle Cell Lymphoma: Results from the EU-MCL network trials. Leukemia 2024, 38, 2675–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sönmez, E.E.; Hatipoğlu, T.; Kurşun, D.; Hu, X.; Akman, B.; Yuan, H.; Danyeli, A.E.; Alacacıoğlu, İ.; Özkal, S.; Olgun, A.; et al. Whole Transcriptome Sequencing Reveals Cancer-Related, Prognostically Significant Transcripts and Tumor-Infiltrating Immunocytes in Mantle Cell Lymphoma. Cells 2022, 11, 3394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mareckova, A.; Malcikova, J.; Tom, N.; Pal, K.; Radova, L.; Salek, D.; Janikova, A.; Moulis, M.; Smardova, J.; Kren, L.; et al. ATM and TP53 mutations show mutual exclusivity but distinct clinical impact in mantle cell lymphoma patients. Leuk. Lymphoma 2019, 60, 1420–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeu, F.; Martin-Garcia, D.; Clot, G.; Díaz-Navarro, A.; Duran-Ferrer, M.; Navarro, A.; Vilarrasa-Blasi, R.; Kulis, M.; Royo, R.; Gutiérrez-Abril, J.; et al. Genomic and epigenomic insights into the origin, pathogenesis, and clinical behavior of mantle cell lymphoma subtypes. Blood 2020, 136, 1419–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.G.; Chang, C.-C.; Ahmad, S.; Mori, S. Leukemic Non-nodal Mantle Cell Lymphoma: Diagnosis and Treatment. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2019, 20, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, K.M.; Portell, C.A.; Williams, M.E. Leukemic Variant of Mantle Cell Lymphoma: Clinical Presentation and Management. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2021, 23, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelenetz, A.D.; Gordon, L.I.; Abramson, J.S.; Advani, R.H.; Andreadis, B.; Bartlett, N.L.; Budde, L.E.; Caimi, P.F.; Chang, J.E.; Christian, B.; et al. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: B-Cell Lymphomas, Version 6.2023. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2023, 21, 1118–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, C.; Silkenstedt, E.; Dreyling, M.; Beà, S. Biological and clinical determinants shaping heterogeneity in mantle cell lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2024, 8, 3652–3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfau-Larue, M.-H.; Klapper, W.; Berger, F.; Jardin, F.; Briere, J.; Salles, G.; Casasnovas, O.; Feugier, P.; Haioun, C.; Ribrag, V.; et al. High-dose cytarabine does not overcome the adverse prognostic value of CDKN2A and TP53 deletions in mantle cell lymphoma. Blood 2015, 126, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malarikova, D.; Berkova, A.; Obr, A.; Blahovcova, P.; Svaton, M.; Forsterova, K.; Kriegova, E.; Prihodova, E.; Pavlistova, L.; Petrackova, A.; et al. Concurrent TP53 and CDKN2A Gene Aberrations in Newly Diagnosed Mantle Cell Lymphoma Correlate with Chemoresistance and Call for Innovative Upfront Therapy. Cancers 2020, 12, 2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaudio, F.; Dicataldo, M.; Di Giovanni, F.; Cazzato, G.; D’AMati, A.; Perrone, T.; Masciopinto, P.; Laddaga, F.E.; Musto, P.; Maiorano, E.; et al. Prognostic Role of CDKN2A Deletion and p53 Expression and Association with MIPIb in Mantle Cell Lymphoma. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2023, 23, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visco, C.; Tisi, M.C.; Evangelista, A.; Di Rocco, A.; Zoellner, A.; Zilioli, V.R.; Hohaus, S.; Sciarra, R.; Re, A.; Tecchio, C.; et al. Time to progression of mantle cell lymphoma after high-dose cytarabine-based regimens defines patients risk for death. Br. J. Haematol. 2019, 185, 940–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QIAamp® DNA FFPE Advanced Handbook. May 2020. Available online: https://www.qiagen.com/pe/resources/download.aspx?id=1fae2a93-1ea1-4f85-8256-4b54c4b76f22&lang=en (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Personal Genomics—Your Solution Provider in the World of Genomics. Available online: https://www.personalgenomics.it/ (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- CNVkit: Genome-Wide Copy Number from High-Throughput Sequencing—CNVkit 0.9.8 Documentation. Available online: https://cnvkit.readthedocs.io/en/stable/ (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- IGV: Integrative Genomics Viewer. Available online: https://igv.org/ (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Cox, D.R. Regression Models and Life-Tables. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 1972, 34, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therneau, T.M.; Grambsch, P.M. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.; Wang, M. High-risk MCL: Recognition and treatment. Blood 2025, 145, 683–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venables, W.N.; Ripley, B.D. Modern Applied Statistics with S, 4th ed.; Statistics and Computing; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, J.M.; Hassan, M.; Freiburghaus, C.; Eskelund, C.W.; Geisler, C.; Räty, R.; Kolstad, A.; Sundström, C.; Glimelius, I.; Grønbæk, K.; et al. p53 is associated with high-risk and pinpoints TP53 missense mutations in mantle cell lymphoma. Br. J. Haematol. 2020, 191, 796–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.; Dreyling, M.; Seymour, J.F.; Wang, M. High-Risk Mantle Cell Lymphoma: Definition, Current Challenges, and Management. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 4302–4316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreyling, M.; Doorduijn, J.; Giné, E.; Jerkeman, M.; Walewski, J.; Hutchings, M.; Mey, U.; Riise, J.; Trneny, M.; Vergote, V.; et al. Ibrutinib combined with immunochemotherapy with or without autologous stem-cell transplantation versus immunochemotherapy and autologous stem-cell transplantation in previously untreated patients with mantle cell lymphoma (TRIANGLE): A three-arm, randomised, open-label, phase 3 superiority trial of the European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Network. Lancet 2024, 403, 2293–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.H.; Kim, S.J.; Lee, J.-O.; Lee, G.-W.; Kwak, J.-Y.; Eom, H.-S.; Jo, J.-C.; Choi, Y.S.; Oh, S.Y.; Kim, W.S. Bendamustine Plus Rituximab for Mantle Cell Lymphoma: A Korean, Multicenter Retrospective Analysis. Anticancer. Res. 2022, 42, 6083–6089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.; Yan, Y.; Jin, M.; Bhattacharya, S.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Yang, L.; Gine, E.; Clot, G.; Chen, L.; et al. Genomic and transcriptomic profiling reveals distinct molecular subsets associated with outcomes in mantle cell lymphoma. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 132, e153283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Bris, Y.; Magrangeas, F.; Moreau, A.; Chiron, D.; Guérin-Charbonnel, C.; Theisen, O.; Pichon, O.; Canioni, D.; Burroni, B.; Maisonneuve, H.; et al. Whole genome copy number analysis in search of new prognostic biomarkers in first line treatment of mantle cell lymphoma. A study by the LYSA group. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 38, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moia, R.; Carazzolo, M.E.; Cosentino, C.; Almasri, M.; Talotta, D.; Tabanelli, V.; Motta, G.; Melle, F.; Sacchi, M.V.; Evangelista, A.; et al. TP53, CD36 Mutations and CDKN2A Loss Predict Poor Outcome in Mantle Cell Lymphoma: Molecular Analysis of the FIL V-Rbac Phase 2 Trial. Blood 2024, 144, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moia, R.; Ragaini, S.; Cascione, L.; Rinaldi, A.; Alessandria, B.; Talotta, D.; Zaccaria, G.M.; Evangelista, A.; Genuardi, E.; Luppi, M.; et al. TP53 and CDKN2A Disruptions are Independent Prognostic Drivers in Mantle Cell Lymphoma: Long Term Outcome of the Fondazione Italiana Linfomi (FIL) MCL0208 Trial. 2024, Volume 419212, p. 1125. Available online: https://library.ehaweb.org/eha/2024/eha2024-congress/419212/riccardo.moia.tp53andcdkn2adisruptions.are.independent.prognostic.drivers.in.html (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Xu-Monette, Z.Y.; Wu, L.; Visco, C.; Tai, Y.C.; Tzankov, A.; Liu, W.-M.; Montes-Moreno, S.; Dybkær, K.; Chiu, A.; Orazi, A.; et al. Mutational Profile and Prognostic Significance of TP53 in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma Patients Treated with R-CHOP: Report from an International DLBCL Rituximab-CHOP Consortium Program Study. Blood 2012, 120, 3986–3996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuger, I.Z.M.; Slieker, R.C.; van Groningen, T.; van Doorn, R. Therapeutic Strategies for Targeting CDKN2A Loss in Melanoma. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2023, 143, 18–25.E1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minami, J.K.; Morrow, D.; Bayley, N.A.; Fernandez, E.G.; Salinas, J.J.; Tse, C.; Zhu, H.; Su, B.; Plawat, R.; Jones, A.; et al. CDKN2A deletion remodels lipid metabolism to prime glioblastoma for ferroptosis. Cancer Cell 2023, 41, 1048–1060.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangudu, N.K.; Buj, R.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Cole, A.R.; Uboveja, A.; Fang, R.; Amalric, A.; Yang, B.; Chatoff, A.; et al. De Novo Purine Metabolism is a Metabolic Vulnerability of Cancers with Low p16 Expression. Cancer Res. Commun. 2024, 4, 1174–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total (n = 73) | Early POD Tot (n = 27) | Late POD Tot (n = 46) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 55 (75%) | 19 (70%) | 36 (78%) | p = 0.57 |

| Female | 18 (25%) | 8 (30%) | 10 (22%) | |

| Age | ||||

| <65 | 30 (41%) | 9 (33%) | 21 (46%) | p = 0.33 |

| ≥65 | 43 (59%) | 18 (67%) | 25 (54%) | |

| Alive | 18 (25%) | 3 (11%) | 15 (33%) | p = 0.05 |

| Dead | 55 (75%) | 24 (89%) | 31 (67%) | |

| MIPI | ||||

| Low | 17 (23%) | 2 (7%) | 15 (33%) | |

| Intermediate | 14 (19) | 4 (15%) | 10 (22%) | p = 0.03 * |

| High | 34 (45%) | 16 (59%) | 18 (39%) | |

| NA | 8 (11%) | 5 (19%) | 3 (6%) | |

| Morphology | ||||

| Blastoid | 6 (8%) | 3 (11%) | 3 (7%) | p = 0.003 * |

| Classic | 59 (81%) | 17 (63%) | 42 (91%) | |

| Pleomorphic | 8 (11%) | 7 (26%) | 1 (2%) | |

| Ki-67% | ||||

| <30 | 33 (45%) | 9 (33%) | 24 (52%) | |

| ≥30 | 34 (47%) | 14 (52%) | 20 (44%) | p = 0.30 |

| NA | 6 (8%) | 4 (15%) | 2 (4%) | |

| Median time to POD 24 | 34.8 months | 12.7 months | 47.5 months | NA |

| TP53 mut | 21 (29%) | 14 (52%) | 7 (15%) | p = 0.001 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carazzolo, M.E.; Quaglia, F.M.; Aparo, A.; Moioli, A.; Parisi, A.; Moia, R.; Piazza, F.; Re, A.; Tisi, M.C.; Nassi, L.; et al. Secondary Genetic Events and Their Relationship to TP53 Mutation in Mantle Cell Lymphoma: A Sub-Study from the FIL_MANTLE-FIRST BIO on Behalf of Fondazione Italiana Linfomi (FIL). Cancers 2025, 17, 4027. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17244027

Carazzolo ME, Quaglia FM, Aparo A, Moioli A, Parisi A, Moia R, Piazza F, Re A, Tisi MC, Nassi L, et al. Secondary Genetic Events and Their Relationship to TP53 Mutation in Mantle Cell Lymphoma: A Sub-Study from the FIL_MANTLE-FIRST BIO on Behalf of Fondazione Italiana Linfomi (FIL). Cancers. 2025; 17(24):4027. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17244027

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarazzolo, Maria Elena, Francesca Maria Quaglia, Antonino Aparo, Alessia Moioli, Alice Parisi, Riccardo Moia, Francesco Piazza, Alessandro Re, Maria Chiara Tisi, Luca Nassi, and et al. 2025. "Secondary Genetic Events and Their Relationship to TP53 Mutation in Mantle Cell Lymphoma: A Sub-Study from the FIL_MANTLE-FIRST BIO on Behalf of Fondazione Italiana Linfomi (FIL)" Cancers 17, no. 24: 4027. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17244027

APA StyleCarazzolo, M. E., Quaglia, F. M., Aparo, A., Moioli, A., Parisi, A., Moia, R., Piazza, F., Re, A., Tisi, M. C., Nassi, L., Bulian, P., Castellino, A., Zilioli, V. R., Stefani, P. M., Fabbri, A., Lucchini, E., Arcari, A., Lorenzi, L., Famengo, B., ... Visco, C. (2025). Secondary Genetic Events and Their Relationship to TP53 Mutation in Mantle Cell Lymphoma: A Sub-Study from the FIL_MANTLE-FIRST BIO on Behalf of Fondazione Italiana Linfomi (FIL). Cancers, 17(24), 4027. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17244027