Determinants of Response to Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Pleural Mesothelioma: Molecular, Immunological, and Clinical Perspectives

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Current Clinical Efficacy of ICB in PM

| Trial | Phase | Therapy | Histotypes * | ORR | Median PFS (mos) | Median OS/Outcome (mos) | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Check-Mate 743 | III | Nivolumab + Ipilimumab vs. Platinum/Pemetrexed | Epithelioid ~75%, Non-epithe- lioid ~25% | 38% vs. 43% | 6.8 mos vs. 7.2 mos | 18.1 mos vs. 14.1 mos (HR 0.74); higher in non-epithelioid (HR 0.46) | [4] |

| DREAM | II | Durvalumab + Platinum/Pemetrexed (single-arm) | Epithelioid 77% Biphasic 13%, Sarcomatoid 10% | 48% | 6.9 mos | 18.4 mos (12-mos OS 70%) | [25] |

| PrE0505 | II | Durvalumab + Platinum/Pemetrexed (single-arm) | Epithelioid 79% Biphasic 12%, Sarcomatoid 9% | 56% | 6.7 mos | 20.4 mos | [26] |

| CONFIRM | III | Nivolumab vs. Placebo (post-chemo) | Epithelioid 85%, Non-epithelioid 15% | 4% vs. 0% | 3.0 mos vs. 1.8 mos | 10.2 mos vs. 6.9 mos (HR 0.69) | [9] |

| MERIT | II | Nivolumab (single-arm, Japan) | Epithelioid 89% Non-epithelioid 11% | 29% | 6.1 mos | 17.3 mos | [14] |

| MAPS2 | II | Nivolumab ± Ipilimumab (post-chemo) | Epithelioid 79% Biphasic 15% Sarcomatoid 6% | 28%/19% | 4.7 mos/2.6 mos | 15.9 mos/11.9 mos | [9] |

4. Epithelioid vs. Non-Epithelioid Pleural Mesothelioma: Potential Genetic and Immune Drivers of Divergent Prognoses and Therapeutic Outcomes

5. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Determinants of ICB Response

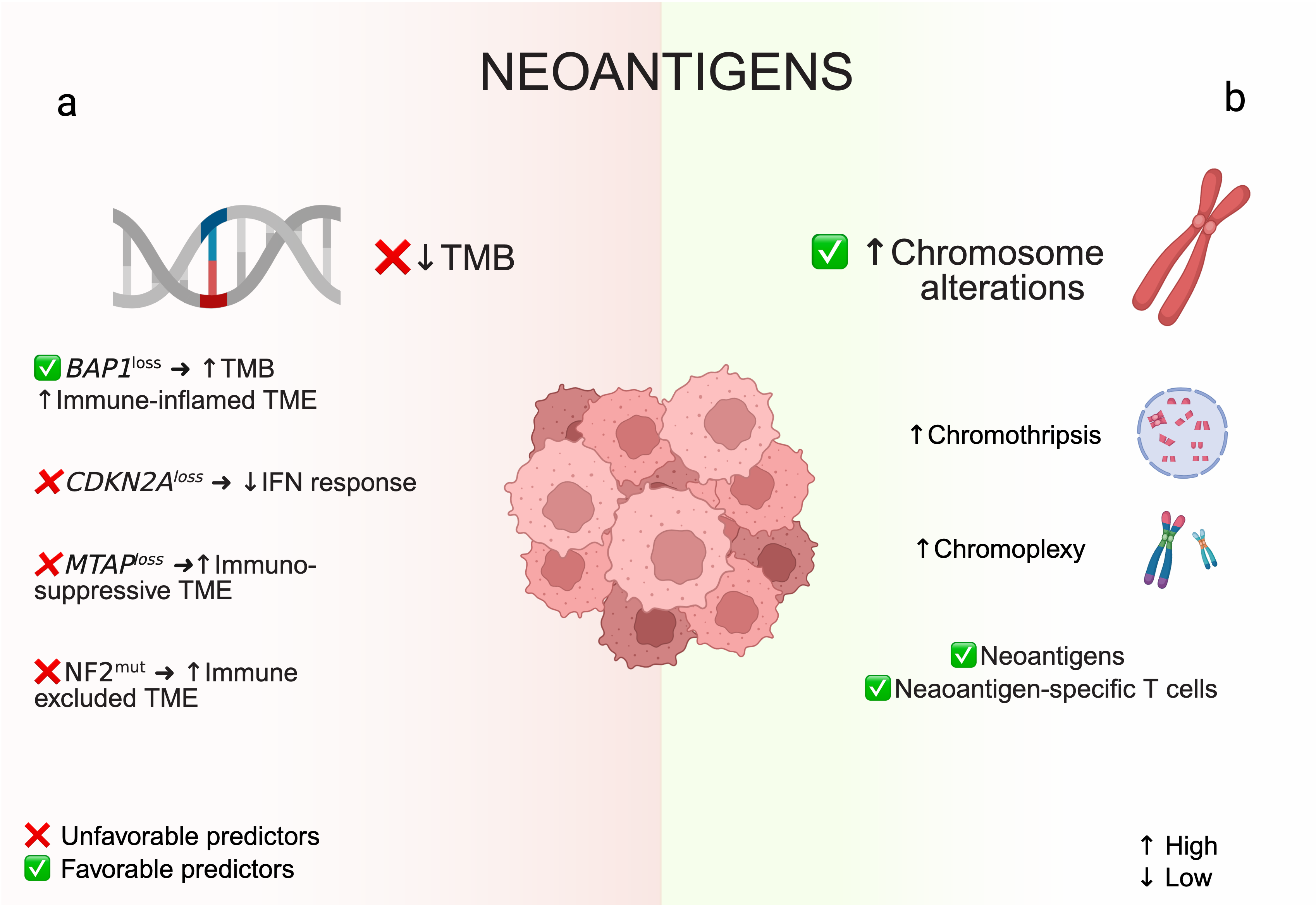

5.1. Neoantigens: Tumor Mutational Burden and Chromosomal Rearrangements

5.2. PD-L1 and Other Inhibitory Immune Checkpoints

5.3. Tumor Suppressor Gene Alterations (BAP1, CDKN2A, NF2)

5.4. Extrinsic Determinants: Tumor Microenvironment and Immune Contexture

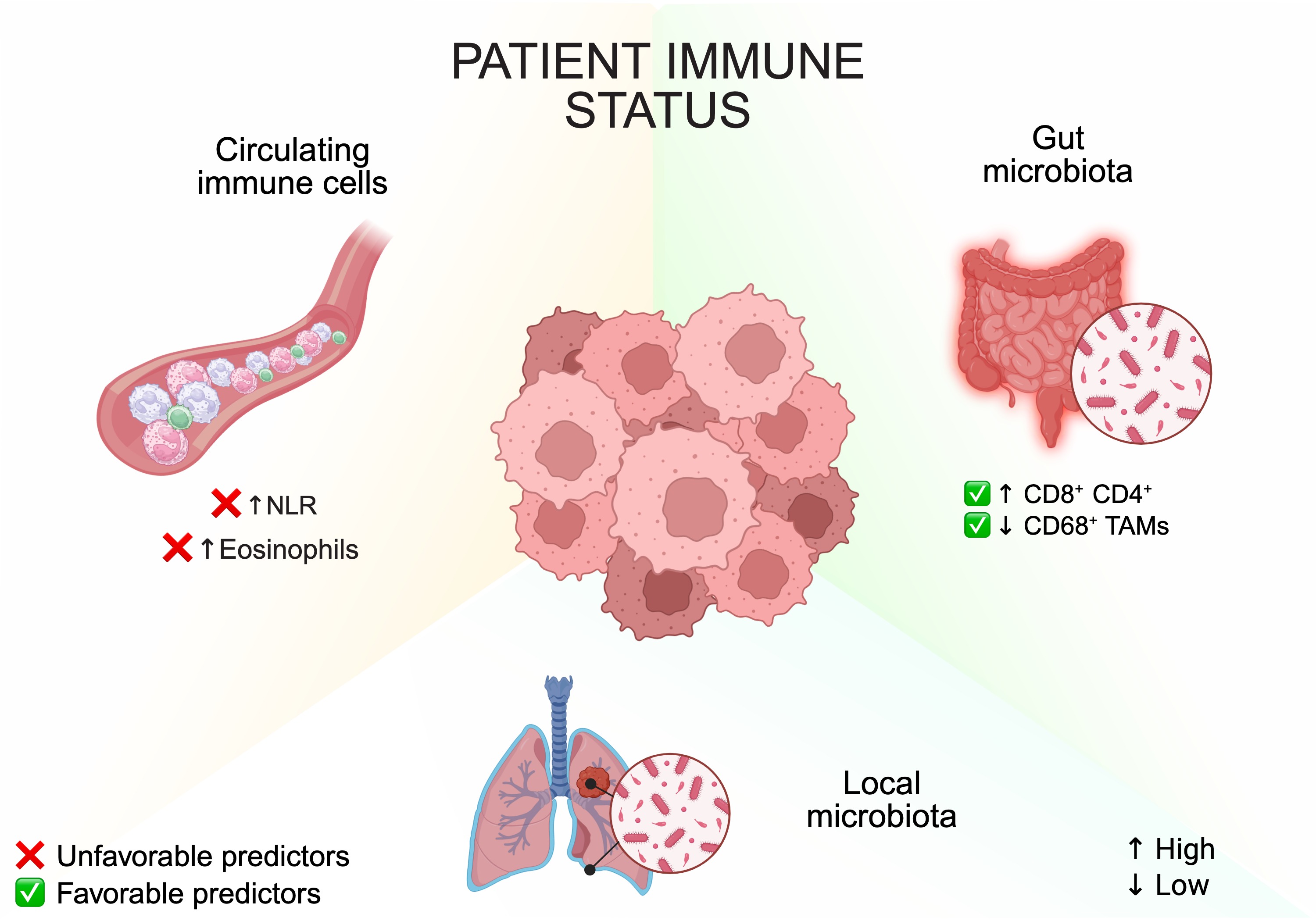

5.5. Patient Factors and Systemic Immune State

6. Strategies to Enhance ICB Response in PM

6.1. ICB Plus Chemotherapy

6.2. Dual and Triple Checkpoint Blockade

6.3. Targeting Immunosuppressive Cells: Macrophages and Tregs

6.4. Anti-Angiogenic and Stroma-Targeting Therapy

6.5. Epigenetic Modulators

6.6. Tumor Vaccines and Cell Therapies

6.7. Oncolytic Viruses and Local Therapies

7. Conclusions and Future Directions

8. Conclusions

- •

- ICB has expanded treatment options for PM, demonstrating activity even in poorly immunogenic tumors. However, overall responses remain modest, largely due to the strong heterogeneity of PM at the histologic, molecular, and immune levels.

- •

- Histology clearly influences therapeutic benefit. Non-epithelioid tumors derive the greatest advantage from dual ICB, whereas epithelioid tumors show only limited improvement. For these patients, multimodal strategies integrating ICB with chemotherapy, radiotherapy, surgery, or new immunomodulatory agents may be required.

- •

- Predicting ICB response will depend on integrated rather than single biomarkers. Composite and spatial immune signatures, liquid biopsy markers, and microbiome-related features appear more informative than PD-L1 or TMB alone, offering more refined tools for patient stratification.

- •

- Several biological questions remain unresolved, including the immunologic impact of BAP1 mutations, the role of sarcomatoid differentiation in biphasic tumors, and the mechanisms underlying hyperprogression. Multiomic approaches will be essential to clarify how tumor-intrinsic alterations shape immune responses.

- •

- Future progress will depend on optimizing combination therapies, refining biomarker-guided treatment selection, and identifying new immunotherapy targets. Defining appropriate maintenance strategies for long-term responders will also be important as more patients achieve durable benefit.

- •

- Overall, advances in tumor profiling and rational treatment integration may gradually shift mesothelioma toward a disease more amenable to durable immune control and, potentially, long-term remission.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, Z.; Cai, Y.; Ou, T.; Zhou, H.; Li, H.; Wang, Z.; Cai, K. Global Burden of Mesothelioma Attributable to Occupational Asbestos Exposure in 204 Countries and Territories: 1990–2019. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 150, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopci, E. Current Status of Staging and Restaging Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2025, 55, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brcic, L.; Kern, I. Clinical Significance of Histologic Subtyping of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2020, 9, 924–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baas, P.; Scherpereel, A.; Nowak, A.K.; Fujimoto, N.; Peters, S.; Tsao, A.S.; Mansfield, A.S.; Popat, S.; Jahan, T.; Antonia, S.; et al. First-Line Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in Unresectable Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma (CheckMate 743): A Multicentre, Randomised, Open-Label, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2021, 397, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwai, Y.; Hamanishi, J.; Chamoto, K.; Honjo, T. Cancer Immunotherapies Targeting the PD-1 Signaling Pathway. J. Biomed. Sci. 2017, 24, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krummel, M.F.; Allison, J.P. CD28 and CTLA-4 Have Opposing Effects on the Response of T Cells to Stimulation. J. Exp. Med. 1995, 182, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, Y. PD-1: Its Discovery, Involvement in Cancer Immunotherapy, and Beyond. Cells 2020, 9, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrino, M.; De Vincenzo, F.; Cordua, N.; Borea, F.; Aliprandi, M.; Santoro, A.; Zucali, P.A. Immunotherapy with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and Predictive Biomarkers in Malignant Mesothelioma: Work Still in Progress. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1121557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherpereel, A.; Antonia, S.; Bautista, Y.; Grossi, F.; Kowalski, D.; Zalcman, G.; Nowak, A.K.; Fujimoto, N.; Peters, S.; Tsao, A.S.; et al. First-Line Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab versus Chemotherapy for the Treatment of Unresectable Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: Patient-Reported Outcomes in CheckMate 743. Lung Cancer Amst. Neth. 2022, 167, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, G.J.; van Zandwijk, N.; Rasko, J.E.J. The Immune Microenvironment in Mesothelioma: Mechanisms of Resistance to Immunotherapy. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Xu, D.; Schmid, R.A.; Peng, R.-W. Biomarker-Guided Targeted and Immunotherapies in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2020, 12, 1758835920971421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alley, E.W.; Lopez, J.; Santoro, A.; Morosky, A.; Saraf, S.; Piperdi, B.; Van Brummelen, E. Clinical Safety and Activity of Pembrolizumab in Patients with Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma (KEYNOTE-028): Preliminary Results from a Non-Randomised, Open-Label, Phase 1b Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, T.A.; Nakagawa, K.; Fujimoto, N.; Kuribayashi, K.; Guren, T.K.; Calabrò, L.; Shapira-Frommer, R.; Gao, B.; Kao, S.; Matos, I.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Pembrolizumab in Patients with Advanced Mesothelioma in the Open-Label, Single-Arm, Phase 2 KEYNOTE-158 Study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021, 9, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, M.; Kijima, T.; Aoe, K.; Kato, T.; Fujimoto, N.; Nakagawa, K.; Takeda, Y.; Hida, T.; Kanai, K.; Imamura, F.; et al. Clinical Efficacy and Safety of Nivolumab: Results of a Multicenter, Open-Label, Single-Arm, Japanese Phase II Study in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma (MERIT). Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 5485–5492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennell, D.A.; Ewings, S.; Ottensmeier, C.; Califano, R.; Hanna, G.G.; Hill, K.; Danson, S.; Steele, N.; Nye, M.; Johnson, L.; et al. Nivolumab versus Placebo in Patients with Relapsed Malignant Mesothelioma (CONFIRM): A Multicentre, Double-Blind, Randomised, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 1530–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, S.; Scherpereel, A.; Cornelissen, R.; Oulkhouir, Y.; Greillier, L.; Kaplan, M.A.; Talbot, T.; Monnet, I.; Hiret, S.; Baas, P.; et al. First-Line Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab versus Chemotherapy in Patients with Unresectable Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: 3-Year Outcomes from CheckMate 743. Ann. Oncol. 2022, 33, 488–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bylicki, O.; Guisier, F.; Scherpereel, A.; Daniel, C.; Swalduz, A.; Grolleau, E.; Bernardi, M.; Hominal, S.; Prevost, J.B.; Pamart, G.; et al. Real-World Efficacy and Safety of Combination Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab for Untreated, Unresectable, Pleural Mesothelioma: The Meso-Immune (GFPC 04-2021) Trial. Lung Cancer Amst. Neth. 2024, 194, 107866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enrico, D.; Gomez, J.E.; Aguirre, D.; Tissera, N.S.; Tsou, F.; Pupareli, C.; Tanco, D.P.; Waisberg, F.; Rodríguez, A.; Rizzo, M.; et al. Efficacy of First-Line Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab in Unresectable Pleural Mesothelioma: A Multicenter Real-World Study (ImmunoMeso LATAM). Clin. Lung Cancer 2024, 25, 723–731.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid, S.; Holer, L.; Gysel, K.; Koster, K.-L.; Rothschild, S.I.; Boos, L.A.; Frehner, L.; Cardoso Almeida, S.; Britschgi, C.; Metaxas, Y.; et al. Real-World Outcomes of Patients With Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma Receiving a Combination of Ipilimumab and Nivolumab as First- or Later-Line Treatment. JTO Clin. Res. Rep. 2024, 5, 100735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNamee, N.; Harvey, C.; Gray, L.; Khoo, T.; Lingam, L.; Zhang, B.; Nindra, U.; Yip, P.Y.; Pal, A.; Clay, T.; et al. Brief Report: Real-World Toxicity and Survival of Combination Immunotherapy in Pleural Mesothelioma—RIOMeso. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2024, 19, 636–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, K.V.C.; Turner, C.; Hughes, B.; Lwin, Z.; Chan, B. Real-World Outcomes for Patients with Pleural Mesothelioma: A Multisite Retrospective Cohort Study. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 20, 723–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumoulin, D.W.; Douma, L.H.; Hofman, M.M.; van der Noort, V.; Cornelissen, R.; de Gooijer, C.J.; Burgers, J.A.; Aerts, J.G.J.V. Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in the Real-World Setting in Patients with Mesothelioma. Lung Cancer Amst. Neth. 2024, 187, 107440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, H. Current Drug Therapy for Pleural Mesothelioma. Respir. Investig. 2025, 63, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofianidi, A.A.; Syrigos, N.K.; Blyth, K.G.; Charpidou, A.; Vathiotis, I.A. Breaking Through: Immunotherapy Innovations in Pleural Mesothelioma. Clin. Lung Cancer 2025, 26, 458–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak, A.K.; Lesterhuis, W.J.; Kok, P.-S.; Brown, C.; Hughes, B.G.; Karikios, D.J.; John, T.; Kao, S.C.-H.; Leslie, C.; Cook, A.M.; et al. Durvalumab with First-Line Chemotherapy in Previously Untreated Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma (DREAM): A Multicentre, Single-Arm, Phase 2 Trial with a Safety Run-In. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 1213–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forde, P.M.; Anagnostou, V.; Sun, Z.; Dahlberg, S.E.; Kindler, H.L.; Niknafs, N.; Purcell, T.; Santana-Davila, R.; Dudek, A.Z.; Borghaei, H.; et al. Durvalumab with Platinum-Pemetrexed for Unresectable Pleural Mesothelioma: Survival, Genomic and Immunologic Analyses from the Phase 2 PrE0505 Trial. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1910–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauter, J.L.; Dacic, S.; Galateau-Salle, F.; Attanoos, R.L.; Butnor, K.J.; Churg, A.; Husain, A.N.; Kadota, K.; Khoor, A.; Nicholson, A.G.; et al. The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Pleura: Advances Since the 2015 Classification. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2022, 17, 608–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabrò, L.; Bronte, G.; Grosso, F.; Cerbone, L.; Delmonte, A.; Nicolini, F.; Mazza, M.; Di Giacomo, A.M.; Covre, A.; Lofiego, M.F.; et al. Immunotherapy of Mesothelioma: The Evolving Change of a Long-Standing Therapeutic Dream. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1333661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dacic, S. Pleural Mesothelioma Classification-Update and Challenges. Mod. Pathol. 2022, 35, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, R.; Stawiski, E.W.; Goldstein, L.D.; Durinck, S.; De Rienzo, A.; Modrusan, Z.; Gnad, F.; Nguyen, T.T.; Jaiswal, B.S.; Chirieac, L.R.; et al. Comprehensive Genomic Analysis of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma Identifies Recurrent Mutations, Gene Fusions and Splicing Alterations. Nat. Genet. 2016, 48, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, Y.; Meiller, C.; Quetel, L.; Elarouci, N.; Ayadi, M.; Tashtanbaeva, D.; Armenoult, L.; Montagne, F.; Tranchant, R.; Renier, A.; et al. Dissecting Heterogeneity in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma through Histo-Molecular Gradients for Clinical Applications. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Bzura, A.; Baitei, E.Y.; Zhou, Z.; Spicer, J.B.; Poile, C.; Rogel, J.; Branson, A.; King, A.; Barber, S.; et al. A Gut Microbiota Rheostat Forecasts Responsiveness to PD-L1 and VEGF Blockade in Mesothelioma. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hmeljak, J.; Sanchez-Vega, F.; Hoadley, K.A.; Shih, J.; Stewart, C.; Heiman, D.; Tarpey, P.; Danilova, L.; Drill, E.; Gibb, E.A.; et al. Integrative Molecular Characterization of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 1548–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagogo-Jack, I.; Madison, R.W.; Lennerz, J.K.; Chen, K.-T.; Hopkins, J.F.; Schrock, A.B.; Ritterhouse, L.L.; Lester, A.; Wharton, K.A.; Mino-Kenudson, M.; et al. Molecular Characterization of Mesothelioma: Impact of Histologic Type and Site of Origin on Molecular Landscape. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2022, 6, e2100422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Gao, Y.; Yang, H.; Spils, M.; Marti, T.M.; Losmanová, T.; Su, M.; Wang, W.; Zhou, Q.; Dorn, P.; et al. BAP1 Deficiency Inflames the Tumor Immune Microenvironment and Is a Candidate Biomarker for Immunotherapy Response in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. JTO Clin. Res. Rep. 2024, 5, 100672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, A.; Creaney, J. Genomic Landscape of Pleural Mesothelioma and Therapeutic Aftermaths. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2023, 25, 1515–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meiller, C.; Montagne, F.; Hirsch, T.Z.; Caruso, S.; de Wolf, J.; Bayard, Q.; Assié, J.-B.; Meunier, L.; Blum, Y.; Quetel, L.; et al. Multi-Site Tumor Sampling Highlights Molecular Intra-Tumor Heterogeneity in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Genome Med. 2021, 13, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quetel, L.; Meiller, C.; Assié, J.-B.; Blum, Y.; Imbeaud, S.; Montagne, F.; Tranchant, R.; de Wolf, J.; Caruso, S.; Copin, M.-C.; et al. Genetic Alterations of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: Association with Tumor Heterogeneity and Overall Survival. Mol. Oncol. 2020, 14, 1207–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, L.; Gu, W.; Li, X.; Xie, L.; Wang, L.; Chen, Z. PD-L1 and Prognosis in Patients with Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: A Meta-Analysis and Bioinformatics Study. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2020, 12, 1758835920962362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosseau, S.; Danel, C.; Scherpereel, A.; Mazières, J.; Lantuejoul, S.; Margery, J.; Greillier, L.; Audigier-Valette, C.; Gounant, V.; Antoine, M.; et al. Shorter Survival in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma Patients with High PD-L1 Expression Associated with Sarcomatoid or Biphasic Histology Subtype: A Series of 214 Cases From the Bio-MAPS Cohort. Clin. Lung Cancer 2019, 20, e564–e575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasello, G.; Zago, G.; Lunardi, F.; Urso, L.; Kern, I.; Vlacic, G.; Grosso, F.; Mencoboni, M.; Ceresoli, G.L.; Schiavon, M.; et al. Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma Immune Microenvironment and Checkpoint Expression: Correlation with Clinical-Pathological Features and Intratumor Heterogeneity over Time. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 1258–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giotti, B.; Dolasia, K.; Zhao, W.; Cai, P.; Sweeney, R.; Merritt, E.; Kiner, E.; Kim, G.S.; Bhagwat, A.; Nguyen, T.; et al. Single-Cell View of Tumor Microenvironment Gradients in Pleural Mesothelioma. Cancer Discov. 2024, 14, 2262–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertuccio, F.R.; Montini, S.; Fusco, M.A.; Di Gennaro, A.; Sciandrone, G.; Agustoni, F.; Galli, G.; Bortolotto, C.; Saddi, J.; Baietto, G.; et al. Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: From Pathophysiology to Innovative Actionable Targets. Cancers 2025, 17, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaleski, M.; Kalhor, N.; Fujimoto, J.; Wistuba, I.; Moran, C.A. Sarcomatoid Mesothelioma: A CDKN2A Molecular Analysis of 53 Cases with Immunohistochemical Correlation with BAP1. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2020, 216, 153267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, F.; Flores, E.; Napolitano, A.; Kanodia, S.; Taioli, E.; Pass, H.; Yang, H.; Carbone, M. Mesothelioma Patients with Germline BAP1 Mutations Have 7-Fold Improved Long-Term Survival. Carcinogenesis 2015, 36, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastorino, S.; Yoshikawa, Y.; Pass, H.I.; Emi, M.; Nasu, M.; Pagano, I.; Takinishi, Y.; Yamamoto, R.; Minaai, M.; Hashimoto-Tamaoki, T.; et al. A Subset of Mesotheliomas with Improved Survival Occurring in Carriers of BAP1 and Other Germline Mutations. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, JCO2018790352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakiroglu, E.; Senturk, S. Genomics and Functional Genomics of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Zhao, Z.; Long, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, B.; Chen, G.; Li, X.; Lv, T.; Zhang, W.; Ou, X.; et al. Molecular Alterations of the NF2 Gene in Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 38, 3650–3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, A.M.; Kittaneh, M.; Cebulla, C.M.; Abdel-Rahman, M.H. An Overview of BAP1 Biological Functions and Current Therapeutics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2025, 1880, 189267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nardone, V.; Porta, C.; Giannicola, R.; Correale, P.; Mutti, L. Abemaciclib for Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, e237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Luo, J.-L.; Sun, Q.; Harber, J.; Dawson, A.G.; Nakas, A.; Busacca, S.; Sharkey, A.J.; Waller, D.; Sheaff, M.T.; et al. Clonal Architecture in Mesothelioma Is Prognostic and Shapes the Tumour Microenvironment. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torricelli, F.; Spada, F.; Bishop, C.; Todd, K.; Nonaka, D.; Petrov, N.; Barberio, M.T.; Ramsay, A.G.; Ellis, R.; Ciarrocchi, A.; et al. The Phenogenomic Landscapes of Pleural Mesothelioma Tumor Microenvironment Predict Clinical Outcomes. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, L.; Fashoyin-Aje, L.A.; Donoghue, M.; Yuan, M.; Rodriguez, L.; Gallagher, P.S.; Philip, R.; Ghosh, S.; Theoret, M.R.; Beaver, J.A.; et al. FDA Approval Summary: Pembrolizumab for the Treatment of Tumor Mutational Burden-High Solid Tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 4685–4689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, A.S.; Peikert, T.; Vasmatzis, G. Chromosomal Rearrangements and Their Neoantigenic Potential in Mesothelioma. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2020, 9, S92–S99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.A.; Patel, V.G. The Role of PD-L1 Expression as a Predictive Biomarker: An Analysis of All US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Approvals of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Q.; Perrone, F.; Greillier, L.; Tu, W.; Piccirillo, M.C.; Grosso, F.; Lo Russo, G.; Florescu, M.; Mencoboni, M.; Morabito, A.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy versus Chemotherapy in Untreated Advanced Pleural Mesothelioma in Canada, Italy, and France: A Phase 3, Open-Label, Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2023, 402, 2295–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tagliamento, M.; Bironzo, P.; Curcio, H.; De Luca, E.; Pignataro, D.; Rapetti, S.G.; Audisio, M.; Bertaglia, V.; Paratore, C.; Bungaro, M.; et al. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Trials Assessing PD-1/PD-L1 Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors Activity in Pre-Treated Advanced Stage Malignant Mesothelioma. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2022, 172, 103639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homicsko, K.; Zygoura, P.; Norkin, M.; Tissot, S.; Shakarishvili, N.; Popat, S.; Curioni-Fontecedro, A.; O’Brien, M.; Pope, A.; Shah, R.; et al. PD-1-Expressing Macrophages and CD8 T Cells Are Independent Predictors of Clinical Benefit from PD-1 Inhibition in Advanced Mesothelioma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e007585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcq, E.; Waele, J.D.; Audenaerde, J.V.; Lion, E.; Santermans, E.; Hens, N.; Pauwels, P.; van Meerbeeck, J.P.; Smits, E.L.J. Abundant Expression of TIM-3, LAG-3, PD-1 and PD-L1 as Immunotherapy Checkpoint Targets in Effusions of Mesothelioma Patients. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 89722–89735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cedres, S.; Valdivia, A.; Priano, I.; Rocha, P.; Iranzo, P.; Pardo, N.; Martinez-Marti, A.; Felip, E. BAP1 Mutations and Pleural Mesothelioma: Genetic Insights, Clinical Implications, and Therapeutic Perspectives. Cancers 2025, 17, 1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Xu, D.; Gao, Y.; Schmid, R.A.; Peng, R.-W. Oncolytic Viral Therapy for Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2020, 15, e111–e113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquelot, N.; Yamazaki, T.; Roberti, M.P.; Duong, C.P.M.; Andrews, M.C.; Verlingue, L.; Ferrere, G.; Becharef, S.; Vétizou, M.; Daillère, R.; et al. Sustained Type I Interferon Signaling as a Mechanism of Resistance to PD-1 Blockade. Cell Res. 2019, 29, 846–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, R.; Nabavi, N.; Lin, Y.-Y.; Mo, F.; Anderson, S.; Volik, S.; Adomat, H.H.; Lin, D.; Xue, H.; Dong, X.; et al. BAP1 Haploinsufficiency Predicts a Distinct Immunogenic Class of Malignant Peritoneal Mesothelioma. Genome Med. 2019, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbue, O.; Unlu, S.; Sorathia, S.; Nanah, A.R.; Abdeljaleel, F.; Haddad, A.S.; Daw, H. Impact of BAP1 Mutational Status on Immunotherapy Outcomes in Advanced Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: A Single Institution Experience. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, e20537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennell, D.A.; King, A.; Mohammed, S.; Greystoke, A.; Anthony, S.; Poile, C.; Nusrat, N.; Scotland, M.; Bhundia, V.; Branson, A.; et al. Abemaciclib in Patients with p16ink4A-Deficient Mesothelioma (MiST2): A Single-Arm, Open-Label, Phase 2 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrich, F.C.; Singer, K.; Poller, K.; Bernhardt, L.; Strobl, C.D.; Limm, K.; Ritter, A.P.; Gottfried, E.; Völkl, S.; Jacobs, B.; et al. Suppressive Effects of Tumor Cell-Derived 5′-Deoxy-5′-Methylthioadenosine on Human T Cells. Oncoimmunology 2016, 5, e1184802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.M.-L.; Chang, Y.-C.; Chan, H.-C.; Chan, H.-C.; Chang, W.-C.; Wang, L.-F.; Tsai, T.-H.; Chen, Y.-J.; Huang, W.-C. FK228 Suppress the Growth of Human Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma Tumor Independent to Epithelioid or Non-Epithelioid Histology. Mol. Med. Camb. Mass 2024, 30, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janse van Rensburg, H.J.; Azad, T.; Ling, M.; Hao, Y.; Snetsinger, B.; Khanal, P.; Minassian, L.M.; Graham, C.H.; Rauh, M.J.; Yang, X. The Hippo Pathway Component TAZ Promotes Immune Evasion in Human Cancer through PD-L1. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 1457–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.H.; Kim, C.G.; Kim, S.-K.; Shin, S.J.; Choe, E.A.; Park, S.-H.; Shin, E.-C.; Kim, J. YAP-Induced PD-L1 Expression Drives Immune Evasion in BRAFi-Resistant Melanoma. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2018, 6, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minnema-Luiting, J.; Vroman, H.; Aerts, J.; Cornelissen, R. Heterogeneity in Immune Cell Content in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiltbrunner, S.; Mannarino, L.; Kirschner, M.B.; Opitz, I.; Rigutto, A.; Laure, A.; Lia, M.; Nozza, P.; Maconi, A.; Marchini, S.; et al. Tumor Immune Microenvironment and Genetic Alterations in Mesothelioma. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 660039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galon, J.; Bruni, D. Approaches to Treat Immune Hot, Altered and Cold Tumours with Combination Immunotherapies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, H.; Gao, Y.; Sun, Z.; Liu, S. Recent Advances in Novel Tumor Immunotherapy Strategies Based on Regulating the Tumor Microenvironment and Immune Checkpoints. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1529403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alay, A.; Cordero, D.; Hijazo-Pechero, S.; Aliagas, E.; Lopez-Doriga, A.; Marín, R.; Palmero, R.; Llatjós, R.; Escobar, I.; Ramos, R.; et al. Integrative Transcriptome Analysis of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma Reveals a Clinically Relevant Immune-Based Classification. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e001601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chee, S.J.; Lopez, M.; Mellows, T.; Gankande, S.; Moutasim, K.A.; Harris, S.; Clarke, J.; Vijayanand, P.; Thomas, G.J.; Ottensmeier, C.H. Evaluating the Effect of Immune Cells on the Outcome of Patients with Mesothelioma. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 117, 1341–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannarino, L.; Paracchini, L.; Pezzuto, F.; Olteanu, G.E.; Moracci, L.; Vedovelli, L.; De Simone, I.; Bosetti, C.; Lupi, M.; Amodeo, R.; et al. Epithelioid Pleural Mesothelioma Is Characterized by Tertiary Lymphoid Structures in Long Survivors: Results from the MATCH Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Gu, X.; Li, D.; Wu, P.; Sun, N.; Zhang, C.; He, J. Tertiary Lymphoid Structures as a Biomarker in Immunotherapy and beyond: Advancing towards Clinical Application. Cancer Lett. 2025, 613, 217491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, R.; Lievense, L.A.; Maat, A.P.; Hendriks, R.W.; Hoogsteden, H.C.; Bogers, A.J.; Hegmans, J.P.; Aerts, J.G. Ratio of Intratumoral Macrophage Phenotypes Is a Prognostic Factor in Epithelioid Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e106742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horio, D.; Minami, T.; Kitai, H.; Ishigaki, H.; Higashiguchi, Y.; Kondo, N.; Hirota, S.; Kitajima, K.; Nakajima, Y.; Koda, Y.; et al. Tumor-Associated Macrophage-Derived Inflammatory Cytokine Enhances Malignant Potential of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Cancer Sci. 2020, 111, 2895–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.; Yang, T.; Yang, T.; Yuan, Y.; Li, F. Unraveling Tumor Microenvironment Heterogeneity in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma Identifies Biologically Distinct Immune Subtypes Enabling Prognosis Determination. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 995651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollila, H.; Mäyränpää, M.I.; Paavolainen, L.; Paajanen, J.; Välimäki, K.; Sutinen, E.; Wolff, H.; Räsänen, J.; Kallioniemi, O.; Myllärniemi, M.; et al. Prognostic Role of Tumor Immune Microenvironment in Pleural Epithelioid Mesothelioma. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 870352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harber, J.; Kamata, T.; Pritchard, C.; Fennell, D. Matter of TIME: The Tumor-Immune Microenvironment of Mesothelioma and Implications for Checkpoint Blockade Efficacy. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e003032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fridman, W.H.; Zitvogel, L.; Sautès-Fridman, C.; Kroemer, G. The Immune Contexture in Cancer Prognosis and Treatment. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 14, 717–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magkouta, S.F.; Vaitsi, P.C.; Pappas, A.G.; Iliopoulou, M.; Kosti, C.N.; Psarra, K.; Kalomenidis, I.T. CSF1/CSF1R Axis Blockade Limits Mesothelioma and Enhances Efficiency of Anti-PDL1 Immunotherapy. Cancers 2021, 13, 2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.; Mohamady Farouk Abdalsalam, N.; Liang, Z.; Kashaf Tariq, H.; Li, R.; O. Afolabi, L.; Rabiu, L.; Chen, X.; Xu, S.; Xu, Z.; et al. MDSC Checkpoint Blockade Therapy: A New Breakthrough Point Overcoming Immunosuppression in Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancer Gene Ther. 2025, 32, 371–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaroglio, I.C.; Kopecka, J.; Napoli, F.; Pradotto, M.; Maletta, F.; Costardi, L.; Gagliasso, M.; Milosevic, V.; Ananthanarayanan, P.; Bironzo, P.; et al. Potential Diagnostic and Prognostic Role of Microenvironment in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2019, 14, 1458–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathria, P.; Louis, T.L.; Varner, J.A. Targeting Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Cancer. Trends Immunol. 2019, 40, 310–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Z.; Todd, L.; Huang, L.; Noguera-Ortega, E.; Lu, Z.; Huang, L.; Kopp, M.; Li, Y.; Pattada, N.; Zhong, W.; et al. Desmoplastic Stroma Restricts T Cell Extravasation and Mediates Immune Exclusion and Immunosuppression in Solid Tumors. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarthy, A.; Khan, L.; Bensler, N.P.; Bose, P.; De Carvalho, D.D. TGF-β-Associated Extracellular Matrix Genes Link Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts to Immune Evasion and Immunotherapy Failure. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Ren, Y.; Yang, P.; Wang, J.; Zhou, H. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grauel, A.L.; Nguyen, B.; Ruddy, D.; Laszewski, T.; Schwartz, S.; Chang, J.; Chen, J.; Piquet, M.; Pelletier, M.; Yan, Z.; et al. TGFβ-Blockade Uncovers Stromal Plasticity in Tumors by Revealing the Existence of a Subset of Interferon-Licensed Fibroblasts. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 6315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, B.-Z.; Pollard, J.W. Macrophage Diversity Enhances Tumor Progression and Metastasis. Cell 2010, 141, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creaney, J.; Patch, A.-M.; Addala, V.; Sneddon, S.A.; Nones, K.; Dick, I.M.; Lee, Y.C.G.; Newell, F.; Rouse, E.J.; Naeini, M.M.; et al. Comprehensive Genomic and Tumour Immune Profiling Reveals Potential Therapeutic Targets in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Genome Med. 2022, 14, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torricelli, F.; Donati, B.; Reggiani, F.; Manicardi, V.; Piana, S.; Valli, R.; Lococo, F.; Ciarrocchi, A. Spatially Resolved, High-Dimensional Transcriptomics Sorts out the Evolution of Biphasic Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: New Paradigms for Immunotherapy. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.J.; Chon, H.J.; Kim, C. Peripheral Blood-Based Biomarkers for Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Georgiev, P.; Ringel, A.E.; Sharpe, A.H.; Haigis, M.C. Age-Associated Remodeling of T Cell Immunity and Metabolism. Cell Metab. 2023, 35, 36–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.E.; Naigeon, M.; Goldschmidt, V.; Roulleaux Dugage, M.; Seknazi, L.; Danlos, F.X.; Champiat, S.; Marabelle, A.; Michot, J.-M.; Massard, C.; et al. Immunosenescence, Inflammaging, and Cancer Immunotherapy Efficacy. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2022, 22, 915–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.D.; Le Berichel, J.; Hamon, P.; Wilk, C.M.; Belabed, M.; Yatim, N.; Saffon, A.; Boumelha, J.; Falcomatà, C.; Tepper, A.; et al. Hematopoietic Aging Promotes Cancer by Fueling IL-1α-Driven Emergency Myelopoiesis. Science 2024, 386, eadn0327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleve, A.; Consonni, F.M.; Porta, C.; Garlatti, V.; Sica, A. Evolution and Targeting of Myeloid Suppressor Cells in Cancer: A Translational Perspective. Cancers 2022, 14, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peranzoni, E.; Ingangi, V.; Masetto, E.; Pinton, L.; Marigo, I. Myeloid Cells as Clinical Biomarkers for Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, N.; Liu, S.; Huang, L.; Li, W.; Yang, W.; Cong, T.; Ding, L.; Qiu, M. Prognostic Significance of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Patients with Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: A Meta-Analysis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 57460–57469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okita, R.; Kawamoto, N.; Okada, M.; Inokawa, H.; Yamamoto, N.; Murakami, T.; Ikeda, E. Preoperative Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio Correlates with PD-L1 Expression in Immune Cells of Patients with Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma and Predicts Prognosis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazandjian, D.; Gong, Y.; Keegan, P.; Pazdur, R.; Blumenthal, G.M. Prognostic Value of the Lung Immune Prognostic Index for Patients Treated for Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, 1481–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezquita, L.; Auclin, E.; Ferrara, R.; Charrier, M.; Remon, J.; Planchard, D.; Ponce, S.; Ares, L.P.; Leroy, L.; Audigier-Valette, C.; et al. Association of the Lung Immune Prognostic Index with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Outcomes in Patients with Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Pan, Y.; Wan, J.; Gong, B.; Li, Y.; Kan, X.; Zheng, C. Prognosis Stratification of Cancer Patients Treated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors through Lung Immune Prognostic Index: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Chen, J.; Xie, C.; Chen, H.; Yang, S.; Jiang, H.; Xu, Y. The Predictive Significance of Various Prognostic Scoring Systems on the Efficacy of Immunotherapy in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients: A Retrospective Study. Health Sci. Rep. 2025, 8, e70713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierro, M.; Baldini, C.; Auclin, E.; Vincent, H.; Varga, A.; Martin Romano, P.; Vuagnat, P.; Besse, B.; Planchard, D.; Hollebecque, A.; et al. Predicting Immunotherapy Outcomes in Older Patients with Solid Tumors Using the LIPI Score. Cancers 2022, 14, 5078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willems, M.; Scherpereel, A.; Wasielewski, E.; Raskin, J.; Brossel, H.; Fontaine, A.; Grégoire, M.; Halkin, L.; Jamakhani, M.; Heinen, V.; et al. Excess of Blood Eosinophils Prior to Therapy Correlates with Worse Prognosis in Mesothelioma. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1148798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grisaru-Tal, S.; Rothenberg, M.E.; Munitz, A. Eosinophil–Lymphocyte Interactions in the Tumor Microenvironment and Cancer Immunotherapy. Nat. Immunol. 2022, 23, 1309–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkrief, A.; Pidgeon, R.; Maleki Vareki, S.; Messaoudene, M.; Castagner, B.; Routy, B. The Gut Microbiome as a Target in Cancer Immunotherapy: Opportunities and Challenges for Drug Development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2025, 24, 685–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentimalli, F.; Krstic-Demonacos, M.; Costa, C.; Mutti, L.; Bakker, E.Y. Intratumor Microbiota as a Novel Potential Prognostic Indicator in Mesothelioma. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1129513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwok, B.; Wu, B.G.; Kocak, I.F.; Sulaiman, I.; Schluger, R.; Li, Y.; Anwer, R.; Goparaju, C.; Ryan, D.J.; Sagatelian, M.; et al. Pleural Fluid Microbiota as a Biomarker for Malignancy and Prognosis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paik, J. Nivolumab Plus Relatlimab: First Approval. Drugs 2022, 82, 925–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Yu, T.-K.; Johnson, B.; Selvamani, S.P.; Zhuang, L.; Lee, K.; Klebe, S.; Smith, S.; Wong, K.; Chen, K.; et al. A Combination of PD-1 and TIGIT Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors Elicits a Strong Anti-Tumour Response in Mesothelioma. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 44, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovers, S.; Van Audenaerde, J.; Verloy, R.; De Waele, J.; Brants, L.; Hermans, C.; Lau, H.W.; Merlin, C.; Möller Ribas, M.; Ponsaerts, P.; et al. Co-Targeting of VEGFR2 and PD-L1 Promotes Survival and Vasculature Normalization in Pleural Mesothelioma. OncoImmunology 2025, 14, 2512104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garofalo, M.; Wieczorek, M.; Anders, I.; Staniszewska, M.; Lazniewski, M.; Prygiel, M.; Zasada, A.A.; Szczepińska, T.; Plewczynski, D.; Salmaso, S.; et al. Novel Combinatorial Therapy of Oncolytic Adenovirus AdV5/3-D24-ICOSL-CD40L with Anti PD-1 Exhibits Enhanced Anti-Cancer Efficacy through Promotion of Intratumoral T-Cell Infiltration and Modulation of Tumour Microenvironment in Mesothelioma Mouse Model. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1259314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alonzo, R.A.; Keam, S.; Gill, S.; Rowshanfarzad, P.; Nowak, A.K.; Ebert, M.A.; Cook, A.M. Fractionated Low-Dose Radiotherapy Primes the Tumor Microenvironment for Immunotherapy in a Murine Mesothelioma Model. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. CII 2025, 74, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, Y.; Kozuki, T.; Aoe, K.; Wada, S.; Harada, D.; Yoshida, M.; Sakurai, J.; Hotta, K.; Fujimoto, N. JME-001 Phase II Trial of First-Line Combination Chemotherapy with Cisplatin, Pemetrexed, and Nivolumab for Unresectable Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e003288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, P.S.; Forde, P.M.; Hughes, B.; Sun, Z.; Brown, C.; Ramalingam, S.; Cook, A.; Lesterhuis, W.J.; Yip, S.; O’Byrne, K.; et al. Protocol of DREAM3R: DuRvalumab with chEmotherapy as First-Line treAtment in Advanced Pleural Mesothelioma-a Phase 3 Randomised Trial. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e057663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felip, E.; Popat, S.; Dafni, U.; Ribi, K.; Pope, A.; Cedres, S.; Shah, R.; de Marinis, F.; Cove Smith, L.; Bernabé, R.; et al. A Randomised Phase III Study of Bevacizumab and Carboplatin-Pemetrexed Chemotherapy with or without Atezolizumab as First-Line Treatment for Advanced Pleural Mesothelioma: Results of the ETOP 13-18 BEAT-Meso Trial. Ann. Oncol. 2025, 36, 548–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frentzas, S.; Kao, S.; Gao, R.; Zheng, H.; Rizwan, A.; Budha, N.; Pedroza, L.d.l.H.; Tan, W.; Meniawy, T. AdvanTIG-105: A Phase I Dose Escalation Study of the Anti-TIGIT Monoclonal Antibody Ociperlimab in Combination with Tislelizumab in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e005829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, A.Z.; Xi, M.X.; Scilla, K.A.; Mamdani, H.; Creelan, B.C.; Saltos, A.; Tanvetyanon, T.; Chiappori, A. Phase 2 Trial of Nivolumab and Ramucirumab for Relapsed Mesothelioma: HCRN-LUN15-299. JTO Clin. Res. Rep. 2023, 4, 100584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douma, L.-A.H.; van der Noort, V.; Lalezari, F.; de Vries, J.F.; Monkhorst, K.; Smesseim, I.; Baas, P.; Schilder, B.; Vermeulen, M.; Burgers, J.A.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus Lenvatinib as Second-Line Treatment in Patients with Pleural Mesothelioma (PEMMELA): Cohort 2 of a Single-Arm, Phase 2 Study. Lancet Oncol. 2025, 26, 1676–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadatos-Pastos, D.; Yuan, W.; Pal, A.; Crespo, M.; Ferreira, A.; Gurel, B.; Prout, T.; Ameratunga, M.; Chénard-Poirier, M.; Curcean, A.; et al. Phase 1, Dose-Escalation Study of Guadecitabine (SGI-110) in Combination with Pembrolizumab in Patients with Solid Tumors. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e004495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde A Phase I/IIA Study to Assess Safety, Tolerability and Preliminary Activity of the Combination of FAK (Defactinib) and PD-1 (Pembrolizumab) Inhibition in Patients with Advanced Solid Malignancies (FAK-PD1). 2018. Available online: https://clin.larvol.com/trial-detail/2015-003928-31 (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- van Gulijk, M.; Belderbos, B.; Dumoulin, D.; Cornelissen, R.; Bezemer, K.; Klaase, L.; Dammeijer, F.; Aerts, J. Combination of PD-1/PD-L1 Checkpoint Inhibition and Dendritic Cell Therapy in Mice Models and in Patients with Mesothelioma. Int. J. Cancer 2023, 152, 1438–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haakensen, V.D.; Öjlert, Å.K.; Thunold, S.; Farooqi, S.; Nowak, A.K.; Chin, W.L.; Grundberg, O.; Szejniuk, W.M.; Cedres, S.; Sørensen, J.B.; et al. UV1 Telomerase Vaccine with Ipilimumab and Nivolumab as Second Line Treatment for Pleural Mesothelioma—A Phase II Randomised Trial. Eur. J. Cancer 2024, 202, 113973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adusumilli, P.S.; Zauderer, M.G.; Rivière, I.; Solomon, S.B.; Rusch, V.W.; O’Cearbhaill, R.E.; Zhu, A.; Cheema, W.; Chintala, N.K.; Halton, E.; et al. A Phase I Trial of Regional Mesothelin-Targeted CAR T-Cell Therapy in Patients with Malignant Pleural Disease, in Combination with the Anti-PD-1 Agent Pembrolizumab. Cancer Discov. 2021, 11, 2748–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mampuya, W.A.; Bouchaab, H.; Schaefer, N.; Kinj, R.; La Rosa, S.; Letovanec, I.; Ozsahin, M.; Bourhis, J.; Coukos, G.; Peters, S.; et al. Abscopal Effect in a Patient with Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma Treated with Palliative Radiotherapy and Pembrolizumab. Clin. Transl. Radiat. Oncol. 2021, 27, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittberg, R.; Chan, E.; Yip, S.; Alex, D.; Ho, C. Radiation Induced Abscopal Effect in a Patient with Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma on Pembrolizumab. Cureus 2022, 14, e22159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.-S.; Jang, H.-J.; Ramineni, M.; Wang, D.Y.; Ramos, D.; Choi, J.M.; Splawn, T.; Espinoza, M.; Almarez, M.; Hosey, L.; et al. A Phase II Window of Opportunity Study of Neoadjuvant PD-L1 versus PD-L1 plus CTLA-4 Blockade for Patients with Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 548–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuss, J.E.; Lee, P.K.; Mehran, R.J.; Hu, C.; Ke, S.; Jamali, A.; Najjar, M.; Niknafs, N.; Wehr, J.; Oner, E.; et al. Perioperative Nivolumab or Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in Resectable Diffuse Pleural Mesothelioma: A Phase 2 Trial and ctDNA Analyses. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 4097–4108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catanzaro, E.; Beltrán-Visiedo, M.; Galluzzi, L.; Krysko, D.V. Immunogenicity of Cell Death and Cancer Immunotherapy with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2025, 22, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitvogel, L.; Apetoh, L.; Ghiringhelli, F.; Kroemer, G. Immunological Aspects of Cancer Chemotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroemer, G.; Galassi, C.; Zitvogel, L.; Galluzzi, L. Immunogenic Cell Stress and Death. Nat. Immunol. 2022, 23, 487–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galluzzi, L.; Guilbaud, E.; Schmidt, D.; Kroemer, G.; Marincola, F.M. Targeting Immunogenic Cell Stress and Death for Cancer Therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2024, 23, 445–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalcman, G.; Mazieres, J.; Margery, J.; Greillier, L.; Audigier-Valette, C.; Moro-Sibilot, D.; Molinier, O.; Corre, R.; Monnet, I.; Gounant, V.; et al. Bevacizumab for Newly Diagnosed Pleural Mesothelioma in the Mesothelioma Avastin Cisplatin Pemetrexed Study (MAPS): A Randomised, Controlled, Open-Label, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2016, 387, 1405–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scagliotti, G.V.; Gaafar, R.; Nowak, A.K.; Nakano, T.; van Meerbeeck, J.; Popat, S.; Vogelzang, N.J.; Grosso, F.; Aboelhassan, R.; Jakopovic, M.; et al. Nintedanib in Combination with Pemetrexed and Cisplatin for Chemotherapy-Naive Patients with Advanced Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma (LUME-Meso): A Double-Blind, Randomised, Placebo-Controlled Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2019, 7, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, C.; Zucali, P.A.; Pagano, M.; Grosso, F.; Pasello, G.; Garassino, M.C.; Tiseo, M.; Soto Parra, H.; Grossi, F.; Cappuzzo, F.; et al. Gemcitabine with or without Ramucirumab as Second-Line Treatment for Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma (RAMES): A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 2 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 1438–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arimura, K.; Hiroshima, K.; Nagashima, Y.; Nakazawa, T.; Ogihara, A.; Orimo, M.; Sato, Y.; Katsura, H.; Kanzaki, M.; Kondo, M.; et al. LAG3 Is an Independent Prognostic Biomarker and Potential Target for Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: A Retrospective Study. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Tan, Y. Promising Immunotherapy Targets: TIM3, LAG3, and TIGIT Joined the Party. Mol. Ther. Oncol. 2024, 32, 200773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovers, S.; Janssens, A.; Raskin, J.; Pauwels, P.; van Meerbeeck, J.P.; Smits, E.; Marcq, E. Recent Advances of Immune Checkpoint Inhibition and Potential for (Combined) TIGIT Blockade as a New Strategy for Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; He, Y.; Tang, Y.; Chen, Z.-S.; Qu, M. VISTA: A Novel Checkpoint for Cancer Immunotherapy. Drug Discov. Today 2024, 29, 104045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noelle, R.J.; Lines, J.L.; Lewis, L.D.; Martell, R.E.; Guillaudeux, T.; Lee, S.W.; Mahoney, K.M.; Vesely, M.D.; Boyd-Kirkup, J.; Nambiar, D.K.; et al. Clinical and Research Updates on the VISTA Immune Checkpoint: Immuno-Oncology Themes and Highlights. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1225081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, S.; Anandhan, S.; Raychaudhuri, D.; Sharma, P. Myeloid Cell-Targeted Therapies for Solid Tumours. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2023, 23, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondy, T.; d’Almeida, S.M.; Briolay, T.; Tabiasco, J.; Meiller, C.; Chéné, A.-L.; Cellerin, L.; Deshayes, S.; Delneste, Y.; Fonteneau, J.-F.; et al. Involvement of the M-CSF/IL-34/CSF-1R Pathway in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e000182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joalland, N.; Quéméner, A.; Deshayes, S.; Humeau, R.; Maillasson, M.; LeBihan, H.; Salama, A.; Fresquet, J.; Remy, S.; Mortier, E.; et al. New Soluble CSF-1R-Dimeric Mutein with Enhanced Trapping of Both CSF-1 and IL-34 Reduces Suppressive Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Pleural Mesothelioma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, e010112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jian, C.-Z.; Lin, L.; Hsu, C.-L.; Chen, Y.-H.; Hsu, C.; Tan, C.-T.; Ou, D.-L. A Potential Novel Cancer Immunotherapy: Agonistic Anti-CD40 Antibodies. Drug Discov. Today 2024, 29, 103893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McVey, J.C.; Beatty, G.L. Facts and Hopes of CD40 Agonists in Cancer Immunotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 31, 2079–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackaman, C.; Cornwall, S.; Graham, P.T.; Nelson, D.J. CD40-Activated B Cells Contribute to Mesothelioma Tumor Regression. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2011, 89, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khong, A.; Brown, M.D.; Vivian, J.B.; Robinson, B.W.S.; Currie, A.J. Agonistic Anti-CD40 Antibody Therapy Is Effective against Postoperative Cancer Recurrence and Metastasis in a Murine Tumor Model. J. Immunother. 2013, 36, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pronk, N.B.; Polman, A.J.; Sterk, L.; Oosterhuis, J.W.A.; Smit, E.F. A Nonresponding Small Cell Lung Carcinoma. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2009, 4, 1291–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broomfield, S.; Most, R.; Prosser, A.; Mahendran, S.; Tovey, M.; Smyth, M.; Robinson, B.; Currie, A. Locally Administered TLR7 Agonists Drive Systemic Antitumor Immune Responses That Are Enhanced by Anti-CD40 Immunotherapy. J. Immunol. 2009, 182, 5217–5224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khong, A.; Cleaver, A.L.; Fahmi Alatas, M.; Wylie, B.C.; Connor, T.; Fisher, S.A.; Broomfield, S.; Lesterhuis, W.J.; Currie, A.J.; Lake, R.A.; et al. The Efficacy of Tumor Debulking Surgery Is Improved by Adjuvant Immunotherapy Using Imiquimod and Anti-CD40. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackaman, C.; Lansley, S.; Allan, J.E.; Robinson, B.W.S.; Nelson, D.J. IL-2/CD40-Driven NK Cells Install and Maintain Potency in the Anti-Mesothelioma Effector/Memory Phase. Int. Immunol. 2012, 24, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak, A.K.; Cook, A.M.; McDonnell, A.M.; Millward, M.J.; Creaney, J.; Francis, R.J.; Hasani, A.; Segal, A.; Musk, A.W.; Turlach, B.A.; et al. A Phase 1b Clinical Trial of the CD40-Activating Antibody CP-870,893 in Combination with Cisplatin and Pemetrexed in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 2483–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luke, J.J.; Barlesi, F.; Chung, K.; Tolcher, A.W.; Kelly, K.; Hollebecque, A.; Le Tourneau, C.; Subbiah, V.; Tsai, F.; Kao, S.; et al. Phase I Study of ABBV-428, a Mesothelin-CD40 Bispecific, in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e002015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Randulfe, I.; Lavender, H.; Symeonides, S.; Blackhall, F. Impact of Systemic Anticancer Therapy Timing on Cancer Vaccine Immunogenicity: A Review. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2025, 17, 17588359251316988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, R.; Hegmans, J.P.J.J.; Maat, A.P.W.M.; Kaijen-Lambers, M.E.H.; Bezemer, K.; Hendriks, R.W.; Hoogsteden, H.C.; Aerts, J.G.J.V. Extended Tumor Control after Dendritic Cell Vaccination with Low-Dose Cyclophosphamide as Adjuvant Treatment in Patients with Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 193, 1023–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noordam, L.; Kaijen, M.E.H.; Bezemer, K.; Cornelissen, R.; Maat, L.A.P.W.M.; Hoogsteden, H.C.; Aerts, J.G.J.V.; Hendriks, R.W.; Hegmans, J.P.J.J.; Vroman, H. Low-Dose Cyclophosphamide Depletes Circulating Naïve and Activated Regulatory T Cells in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma Patients Synergistically Treated with Dendritic Cell-Based Immunotherapy. OncoImmunology 2018, 7, e1474318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albiges, L.; Gurney, H.; Atduev, V.; Suarez, C.; Climent, M.A.; Pook, D.; Tomczak, P.; Barthelemy, P.; Lee, J.L.; Stus, V.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus Lenvatinib as First-Line Therapy for Advanced Non-Clear-Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma (KEYNOTE-B61): A Single-Arm, Multicentre, Phase 2 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2023, 24, 881–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.U.; Han, B.S.; Jung, K.H.; Hong, S.-S. Tumor Stroma as a Therapeutic Target for Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Biomol. Ther. 2024, 32, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, N.; Cheng, X.-B.; Kohi, S.; Koga, A.; Hirata, K. Targeting Hyaluronan for the Treatment of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2016, 6, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symeonides, S.N.; Anderton, S.M.; Serrels, A. FAK-Inhibition Opens the Door to Checkpoint Immunotherapy in Pancreatic Cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2017, 5, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Hegde, S.; Knolhoff, B.L.; Zhu, Y.; Herndon, J.M.; Meyer, M.A.; Nywening, T.M.; Hawkins, W.G.; Shapiro, I.M.; Weaver, D.T.; et al. Targeting Focal Adhesion Kinase Renders Pancreatic Cancers Responsive to Checkpoint Immunotherapy. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 851–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang-Gillam, A.; Lim, K.-H.; McWilliams, R.; Suresh, R.; Lockhart, A.C.; Brown, A.; Breden, M.; Belle, J.I.; Herndon, J.; Bogner, S.J.; et al. Defactinib, Pembrolizumab, and Gemcitabine in Patients with Advanced Treatment Refractory Pancreatic Cancer: A Phase I Dose Escalation and Expansion Study. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 5254–5262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quach, H.T.; Hou, Z.; Bellis, R.Y.; Saini, J.K.; Amador-Molina, A.; Adusumilli, P.S.; Xiong, Y. Next-Generation Immunotherapy for Solid Tumors: Combination Immunotherapy with Crosstalk Blockade of TGFβ and PD-1/PD-L1. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2022, 31, 1187–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, J.P.; Kindler, H.L.; Papasavvas, E.; Sun, J.; Jacobs-Small, M.; Hull, J.; Schwed, D.; Ranganathan, A.; Newick, K.; Heitjan, D.F.; et al. Immunological Effects of the TGFβ-Blocking Antibody GC1008 in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma Patients. OncoImmunology 2013, 2, e26218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, H.P.; Barbash, O.; Creasy, C.L. Targeting Epigenetic Modifications in Cancer Therapy: Erasing the Roadmap to Cancer. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Targeting the Epigenetic Regulation of Antitumour Immunity. 2020—Cerca Con Google. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41573-020-0077-5 (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Villanueva, L.; Álvarez-Errico, D.; Esteller, M. The Contribution of Epigenetics to Cancer Immunotherapy. Trends Immunol. 2020, 41, 676–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, R.; Du, W.; Guo, W. EZH2: A Novel Target for Cancer Treatment. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Khatib, M.O.; Pinton, G.; Moro, L.; Porta, C. Benefits and Challenges of Inhibiting EZH2 in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Cancers 2023, 15, 1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabour-Takanlou, M.; Sabour-Takanlou, L.; Biray-Avci, C. EZH2-Associated Tumor Malignancy: A Prominent Target for Cancer Treatment. Clin. Genet. 2024, 106, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zauderer, M.G.; Szlosarek, P.W.; Le Moulec, S.; Popat, S.; Taylor, P.; Planchard, D.; Scherpereel, A.; Koczywas, M.; Forster, M.; Cameron, R.B.; et al. EZH2 Inhibitor Tazemetostat in Patients with Relapsed or Refractory, BAP1-Inactivated Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: A Multicentre, Open-Label, Phase 2 Study. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 758–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, M.; Gong, M.; Liu, X.; Zhang, T.; Liu, Z.; Song, D. Recent Update on the Development of EZH2 Inhibitors and Degraders for Cancer Therapy. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 299, 118106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingg, D.; Arenas-Ramirez, N.; Sahin, D.; Rosalia, R.A.; Antunes, A.T.; Haeusel, J.; Sommer, L.; Boyman, O. The Histone Methyltransferase Ezh2 Controls Mechanisms of Adaptive Resistance to Tumor Immunotherapy. Cell Rep. 2017, 20, 854–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Mudianto, T.; Ma, X.; Riley, R.; Uppaluri, R. Targeting EZH2 Enhances Antigen Presentation, Antitumor Immunity, and Circumvents Anti-PD-1 Resistance in Head and Neck Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, K.L.; Sheahan, A.V.; Burkhart, D.L.; Baca, S.C.; Boufaied, N.; Liu, Y.; Qiu, X.; Cañadas, I.; Roehle, K.; Heckler, M.; et al. EZH2 Inhibition Activates a dsRNA-STING-Interferon Stress Axis That Potentiates Response to PD-1 Checkpoint Blockade in Prostate Cancer. Nat. Cancer 2021, 2, 444–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortezaee, K. EZH2 Regulatory Roles in Cancer Immunity and Immunotherapy. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2025, 270, 155992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piunti, A.; Meghani, K.; Yu, Y.; Robertson, A.G.; Podojil, J.R.; McLaughlin, K.A.; You, Z.; Fantini, D.; Chiang, M.; Luo, Y.; et al. Immune Activation Is Essential for the Antitumor Activity of EZH2 Inhibition in Urothelial Carcinoma. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabo8043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chibaya, L.; Murphy, K.C.; DeMarco, K.D.; Gopalan, S.; Liu, H.; Parikh, C.N.; Lopez-Diaz, Y.; Faulkner, M.; Li, J.; Morris, J.P.; et al. EZH2 Inhibition Remodels the Inflammatory Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype to Potentiate Pancreatic Cancer Immune Surveillance. Nat. Cancer 2023, 4, 872–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarsheth, N.; Peng, D.; Kryczek, I.; Wu, K.; Li, W.; Zhao, E.; Zhao, L.; Wei, S.; Frankel, T.; Vatan, L.; et al. PRC2 Epigenetically Silences Th1-Type Chemokines to Suppress Effector T-Cell Trafficking in Colon Cancer. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugide, S.; Green, M.R.; Wajapeyee, N. Inhibition of Enhancer of Zeste Homolog 2 (EZH2) Induces Natural Killer Cell-Mediated Eradication of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E3509–E3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, J.; Yang, X.; Chen, J.; He, K.; Gao, X.; Wu, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, H.; Xiao, F.; An, L.; et al. Circular EZH2-Encoded EZH2-92aa Mediates Immune Evasion in Glioblastoma via Inhibition of Surface NKG2D Ligands. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Huang, J.; Zhou, L.; Luo, J.; Wan, Y.Y.; Long, H.; Zhu, B. EZH2 Inhibitor GSK126 Suppresses Antitumor Immunity by Driving Production of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 2009–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mola, S.; Pinton, G.; Erreni, M.; Corazzari, M.; De Andrea, M.; Grolla, A.A.; Martini, V.; Moro, L.; Porta, C. Inhibition of the Histone Methyltransferase EZH2 Enhances Protumor Monocyte Recruitment in Human Mesothelioma Spheroids. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, L.; Hu, Z.; Fang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Song, M.; Chen, Y. Regulation of CCL2 by EZH2 Affects Tumor-Associated Macrophages Polarization and Infiltration in Breast Cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lin, W.-P.; Su, W.; Wu, Z.-Z.; Yang, Q.-C.; Wang, S.; Sun, T.-G.; Huang, C.-F.; Wang, X.-L.; Sun, Z.-J. Sunitinib Attenuates Reactive MDSCs Enhancing Anti-Tumor Immunity in HNSCC. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 119, 110243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumoulin, D.W.; Cornelissen, R.; Bezemer, K.; Baart, S.J.; Aerts, J.G.J.V. Long-Term Follow-Up of Mesothelioma Patients Treated with Dendritic Cell Therapy in Three Phase I/II Trials. Vaccines 2021, 9, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerts, J.G.; Belderbos, R.; Baas, P.; Scherpereel, A.; Bezemer, K.; Enninga, I.; Meijer, R.; Willemsen, M.; Berardi, R.; Fennell, D.; et al. Dendritic Cells Loaded with Allogeneic Tumour Cell Lysate plus Best Supportive Care versus Best Supportive Care Alone in Patients with Pleural Mesothelioma as Maintenance Therapy after Chemotherapy (DENIM): A Multicentre, Open-Label, Randomised, Phase 2/3 Study. Lancet Oncol. 2024, 25, 865–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klampatsa, A.; Albelda, S.M. Current Advances in CAR T Cell Therapy for Malignant Mesothelioma. J. Cell. Immunol. 2020, 2, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morello, A.; Sadelain, M.; Adusumilli, P.S. Mesothelin-Targeted CARs: Driving T Cells to Solid Tumors. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, G.; Xing, S.; Wang, S.; Li, N. Breaking through the Treatment Desert of Conventional Mesothelin-Targeted CAR-T Cell Therapy for Malignant Mesothelioma: A Glimpse into the Future. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 204, 107220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalise, L.; Kato, A.; Ohno, M.; Maeda, S.; Yamamichi, A.; Kuramitsu, S.; Shiina, S.; Takahashi, H.; Ozone, S.; Yamaguchi, J.; et al. Efficacy of Cancer-Specific Anti-Podoplanin CAR-T Cells and Oncolytic Herpes Virus G47Δ Combination Therapy against Glioblastoma. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 2022, 26, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pease, D.F.; Kratzke, R.A. Oncolytic Viral Therapy for Mesothelioma. Front. Oncol. 2017, 7, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuryk, L.; Haavisto, E.; Garofalo, M.; Capasso, C.; Hirvinen, M.; Pesonen, S.; Ranki, T.; Vassilev, L.; Cerullo, V. Synergistic Anti-Tumor Efficacy of Immunogenic Adenovirus ONCOS-102 (Ad5/3-D24-GM-CSF) and Standard of Care Chemotherapy in Preclinical Mesothelioma Model. Int. J. Cancer 2016, 139, 1883–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Somma, S.; Iannuzzi, C.A.; Passaro, C.; Forte, I.M.; Iannone, R.; Gigantino, V.; Indovina, P.; Botti, G.; Giordano, A.; Formisano, P.; et al. The Oncolytic Virus Dl922-947 Triggers Immunogenic Cell Death in Mesothelioma and Reduces Xenograft Growth. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce, S.; Cedrés, S.; Ricordel, C.; Isambert, N.; Viteri, S.; Herrera-Juarez, M.; Martinez-Marti, A.; Navarro, A.; Lederlin, M.; Serres, X.; et al. ONCOS-102 plus Pemetrexed and Platinum Chemotherapy in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: A Randomized Phase 2 Study Investigating Clinical Outcomes and the Tumor Microenvironment. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e007552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesney, J.A.; Ribas, A.; Long, G.V.; Kirkwood, J.M.; Dummer, R.; Puzanov, I.; Hoeller, C.; Gajewski, T.F.; Gutzmer, R.; Rutkowski, P.; et al. Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Global Phase III Trial of Talimogene Laherparepvec Combined with Pembrolizumab for Advanced Melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 528–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.B.; Hernandez, R.; Carlson, P.; Grudzinski, J.; Bates, A.M.; Jagodinsky, J.C.; Erbe, A.; Marsh, I.R.; Arthur, I.; Aluicio-Sarduy, E.; et al. Low-Dose Targeted Radionuclide Therapy Renders Immunologically Cold Tumors Responsive to Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eabb3631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, C.; Gastman, B.; Gogas, H.; Rutkowski, P.; Long, G.V.; Chaney, M.F.; Joshi, H.; Lin, Y.-L.; Snyder, W.; Chesney, J.A. Open-Label, Phase II Study of Talimogene Laherparepvec plus Pembrolizumab for the Treatment of Advanced Melanoma That Progressed on Prior Anti-PD-1 Therapy: MASTERKEY-115. Eur. J. Cancer 2024, 207, 114120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revelant, A.; Gessoni, F.; Montico, M.; Dhibi, R.; Brisotto, G.; Casarotto, M.; Zanchetta, M.; Paduano, V.; Sperti, F.; Evangelista, C.; et al. Radical Hemithorax Radiotherapy Induces an Increase in Circulating PD-1+ T Lymphocytes and in the Soluble Levels of PD-L1 in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma Patients: A Possible Synergy with PD-1/PD-L1 Targeting Treatment? Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1534766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cascone, T.; Awad, M.M.; Spicer, J.D.; He, J.; Lu, S.; Sepesi, B.; Tanaka, F.; Taube, J.M.; Cornelissen, R.; Havel, L.; et al. Perioperative Nivolumab in Resectable Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 1756–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakelee, H.; Liberman, M.; Kato, T.; Tsuboi, M.; Lee, S.-H.; Gao, S.; Chen, K.-N.; Dooms, C.; Majem, M.; Eigendorff, E.; et al. Perioperative Pembrolizumab for Early-Stage Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forde, P.M.; Spicer, J.; Lu, S.; Provencio, M.; Mitsudomi, T.; Awad, M.M.; Felip, E.; Broderick, S.R.; Brahmer, J.R.; Swanson, S.J.; et al. Neoadjuvant Nivolumab plus Chemotherapy in Resectable Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1973–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heymach, J.V.; Harpole, D.; Mitsudomi, T.; Taube, J.M.; Galffy, G.; Hochmair, M.; Winder, T.; Zukov, R.; Garbaos, G.; Gao, S.; et al. Perioperative Durvalumab for Resectable Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 1672–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrosini, P.; Stanzi, A.; Lo Russo, G.; Solli, P.; Occhipinti, M. Towards a New Approach in Pleural Mesothelioma: Perioperative Immunotherapy and Its Implications. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2025, 215, 104864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchi, L.G.; Aliprandi, M.; De Vincenzo, F.; Perrino, M.; Cordua, N.; Borea, F.; Bertocchi, A.; Federico, A.; Marulli, G.; Santoro, A.; et al. Perioperative Treatments in Pleural Mesothelioma: State of the Art and Future Directions. Cancers 2025, 17, 3199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, S.L.; Feng, Z.; Kim, S.; Ha, E.K.; Kamel, K.; Becich, M.; Luketich, J.D.; Pennathur, A. Hyperthermic Intrathoracic Chemoperfusion and the Role of Adjunct Immunotherapy for the Treatment of Pleural Mesothelioma. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Molecular/Cellular Features | Epithelioid | Sarcomatoid | Biphasic | Clinical Relevance | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAP1 loss | ≈60–65% | ≈25–45% | ≈50% | IFN signaling; predictive unclear | [29,34,35] |

| CDKN2A del | ≈40–50% | ≈65–75% | ≈55–60% | Worse OS; PD-1 resistance signal | [11,34,36] |

| NF2 mutation | ≈35% | ≈40% | ≈38% | YAP activation; PD-L1 high | [34,37,38] |

| TP53 mutation | <10% | ≈15–20% | ≈12% | Poor prognosis | [30,33] |

| PD - L1 ≥ 1% | 10–20% | 40–60% | 25–35% | Predictive value mixed | [39,40] |

| VISTA high | Common | Rare | Intermediate | Alternate checkpoint | [31,33] |

| T-cell pattern | Stromal CD4 > CD8 | Intratumoral CD8 high | Heterogeneous | Affects ICI | [8,31,41,42] |

| M2 macrophages | Moderate | High | High | Correlate with resistance | [8,31] |

| Stroma/Fibrosis | Dense collagen | Fibrotic, hypoxic | Variable | Barrier | [27] |

| Median OS (chemo) | ≈18–20 mo | ≈8–10 mo | ≈12–15 mo | Baseline | [8,23,28,29] |

| Strategy | Regimen/Agents | Rationale | Histotype | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dual ICB | Anti-PD-L1 + anti-LAG3 | Dual checkpoint blockade | Sarcomatoid | [113] |

| Dual ICB | anti-PD-1 + anti-TIGIT | Dual checkpoint blockade | Epithelioid | [114] |

| ICB + Anti-VEGF | Anti-VEGFR2 (clone DC101) + anti-PD-L1 (clone 10F.9G2) | Vessel normalization | Sarcomatoid | [115] |

| ICB + CSF-1R inhibitor | Pembrolizumab + CSF-1R inhibitor | TAM reprogramming | Sarcomatoid | [84] |

| Oncolytic virus + ICB | AdV5/3-D24-ICOSL-CD40L + anti-PD-1 | Combining oncolytic virotherapy with ICB | Epithelioid | [116] |

| ICB + radio-therapy | Low-dose, low-fraction radiotherapy | promote immune cell infiltration | Sarcomatoid | [117] |

| Strategy | Regimen/Agents | Rationale | Histotype | Identifier | Status | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemo + anti-PD-(L)1 | Platinum/peme trexed + nivolumab | Immunogenic cell death; tumor debulking; sustained immune control | Epithelioid | JME-001 | Phase II | [118] |

| Chemo + anti-PD-L1 | Platinum/peme-trexed + durvalumab | Immunogenic cell death; debulking; improved ORR/OS | Epithelioid | PrE0505 | Phase II | [26] |

| Chemo + anti-PD-L1 | Platinum/peme-trexed + durvalumab | Immunogenic cell death; antigen release; long-term control | Epithelioid | DREAM | Phase II | [25] |

| Chemo + anti-PD-1 | Pembrolizumab + platinum-based chemotherapy | Additive cytotoxic + immune synergy | Epithelioid | (IND-227) | Phase III | [56] |

| Chemo + anti-PD-L1 | Platinum/peme-trexed + durvalumab | Tumor debulking + ICB maintenance | Epithelioid | DREAM3R/PrE0506; NCT04334759 | Phase III | [119] |

| Chemo + anti-PD-L1 + antiVEGF | Atezolizumab + bevacizumab + carboplatin + pemetrexed | Vascular normalization; improved immune infiltration | Non-epithelioid | BEAT-meso; NCT03762018 | Phase III | [120] |

| Anti-PD-1 + anti-TIGIT | Tislelizumab + ociperlimab | Dual checkpoint blockade; overcome PD-1 resistance | Epithelioid | AdvanTIG-105 | Phase I | [121] |

| Anti-PD-1 + anti-VEGFR2 | Nivolumab + ramucirumab | Overcome immune resistance via VEGF inhibition | Non-epithelioid | HCRN-LUN15-299 | Phase II | [122] |

| Anti-PD-1 + anti- angiogenic TKI | Pembrolizumab + lenvatinib | Immune modulation via VEGF blockade | All histotypes | PEMMELA | Phase II | [123] |

| DNMT inhibitor + anti–PD-1 | Guadecitabine + pembrolizumab | Epigenetic reprogramming; restore immunogenicity | PM and advanced solid tumors | NCT02998567 | Phase I | [124] |

| FAK inhibitor + ICB | Defactinib + pembrolizumab | Disrupt tumor stroma; enhance immune infiltration | PM and advanced solid tumors | NCT02758587 | Phase I/IIA (ongoing) | [125] |

| DC vaccine + ICB + chemotherapy | WT1/DC vaccine + atezolizumab + chemotherapy | Increase TILs | Epithelioid | Immuno-MESODEC; NCT05765084 | Phase I/II (ongoing) | [126] |

| Peptide vaccine + dual ICB | UV1 (telomerase vaccine) + ipilimumab + nivolumab | Enhance T cell priming | Previously treated PM | NIPU trial | Phase II | [127] |

| CAR-T + ICB | Intrapleural anti-mesothelin CAR-T followed by PD-1 blockade | Prevent CAR-T exhaustion; amplify immune response | Epitheloid | NCT02414269 | Phase I | [128] |

| ICB + Radio therapy | Radiotherapy + Pembrolizumab | Abscopal effects | Not specified | case report | [129,130] | |

| Neo adjuvant ICB | Durvalumab ± tremelimumab | Increase intratumoral CD8+ T cells pre-surgery | Resectable PM | NCT02592551 | Phase II | [131] |

| Neo adjuvant ICB | Nivolumab or ipilimumab + nivolumab | Increase anti-tumor immunity pre-surgery | Resectable PM | NCT03918252 | Phase II | [132] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Delsignore, M.; Cassinari, G.; Revello, S.; Cerbone, L.; Grosso, F.; Arsura, M.; Porta, C. Determinants of Response to Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Pleural Mesothelioma: Molecular, Immunological, and Clinical Perspectives. Cancers 2025, 17, 4020. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17244020

Delsignore M, Cassinari G, Revello S, Cerbone L, Grosso F, Arsura M, Porta C. Determinants of Response to Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Pleural Mesothelioma: Molecular, Immunological, and Clinical Perspectives. Cancers. 2025; 17(24):4020. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17244020

Chicago/Turabian StyleDelsignore, Martina, Gaia Cassinari, Simona Revello, Luigi Cerbone, Federica Grosso, Marcello Arsura, and Chiara Porta. 2025. "Determinants of Response to Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Pleural Mesothelioma: Molecular, Immunological, and Clinical Perspectives" Cancers 17, no. 24: 4020. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17244020

APA StyleDelsignore, M., Cassinari, G., Revello, S., Cerbone, L., Grosso, F., Arsura, M., & Porta, C. (2025). Determinants of Response to Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Pleural Mesothelioma: Molecular, Immunological, and Clinical Perspectives. Cancers, 17(24), 4020. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17244020