The Outcome and Impact of Academic Cancer Clinical Trials with Participation from Canadian Sites (2015–2024)

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Identified trends and gaps in completed trials, including patterns in evidence dissemination and translation into clinical practice.

- Assessed the contributions of 3CTN-supported trials to peer-reviewed publications and clinical treatment guidelines.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Inclusion Criteria

2.2. Operational Definitions and Classification

- Closed: Trials that stopped recruiting, including those with statuses of closed to recruitment, terminated, or completed.

- Closed to Recruitment: Trials that stopped enrolling participants but may still be in follow-up

- Completed: Trials that reached planned accrual and primary endpoint analysis.

- Prematurely Completed: Trials withdrawn before recruitment or terminated before planned accrual (e.g., due to poor accrual or toxicity).

- Positive: Results are reported in the literature and demonstrate a positive primary outcome.

- Negative: Results are reported in the literature and demonstrate a negative primary outcome.

- Inconclusive: Direction or significance of the primary outcome could not be determined from available data, including trials terminated before reaching target accrual.

- Not available: No peer-reviewed results were found, and the primary study completion date is <24 months ago.

- No results: No peer-reviewed results were found, and the primary study completion date is ≥24 months ago.

- Pending final publication: No final, peer-reviewed results for the entire study population, but interim or subgroup results are available, or a peer-reviewed source explicitly states that results are pending or expected.

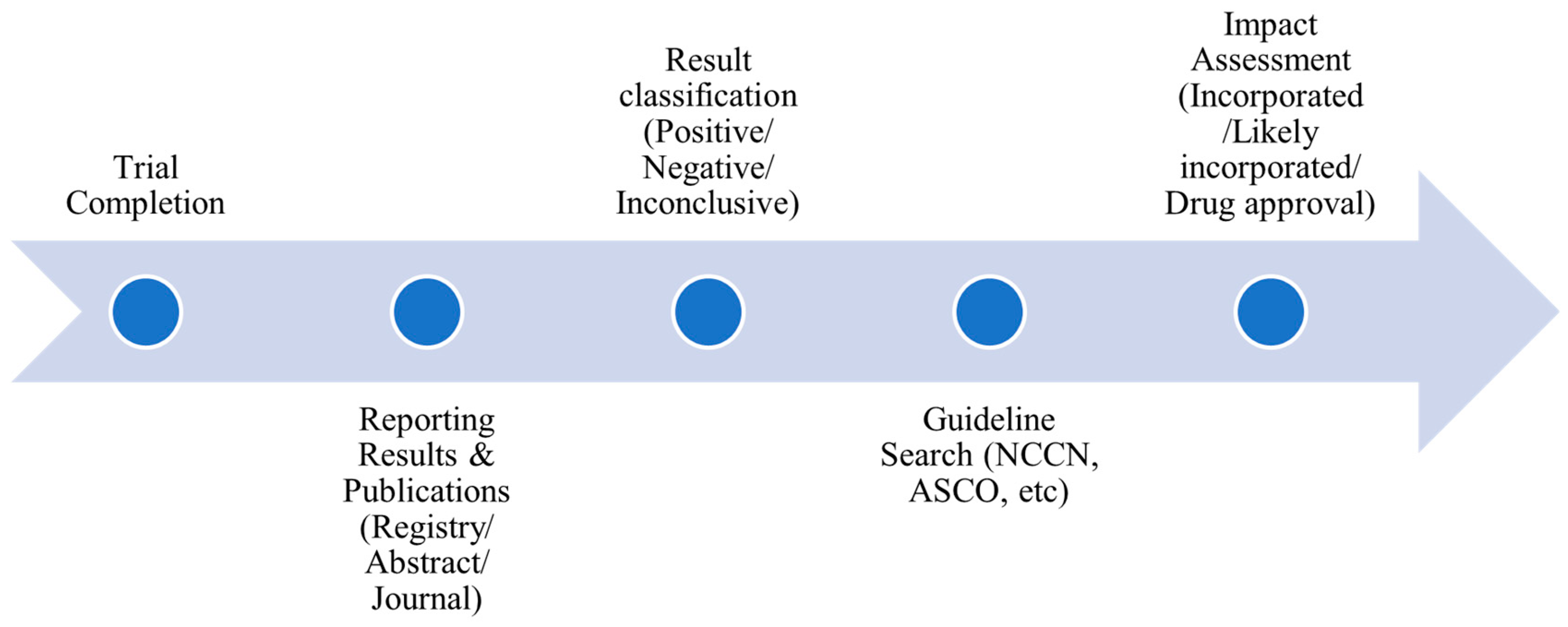

2.3. Assessment of Study Results and Practice Impact

- Incorporated into Practice Guidelines: results cited in the evidence that informed a guideline recommendation (not just cited as background evidence).

- Likely to be Incorporated into Practice Guidelines: Peer-reviewed sources explicitly indicated that trial results are currently influencing clinical decisions or expected to appear in future guideline updates.

2.4. Data Quality Control

3. Results

3.1. Trial Characteristics

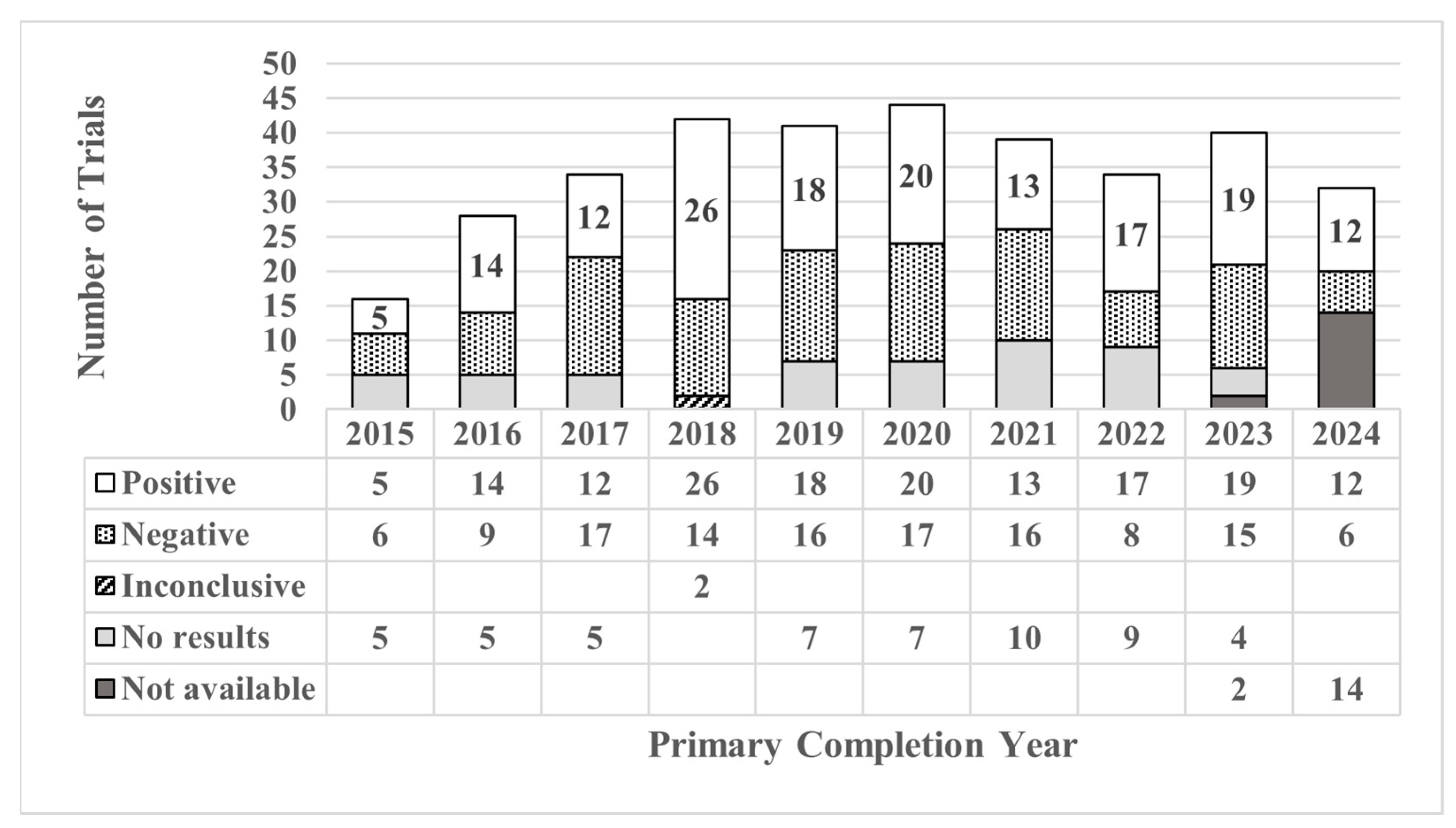

3.2. Trial Outcomes

3.2.1. Reporting and Publication Rates

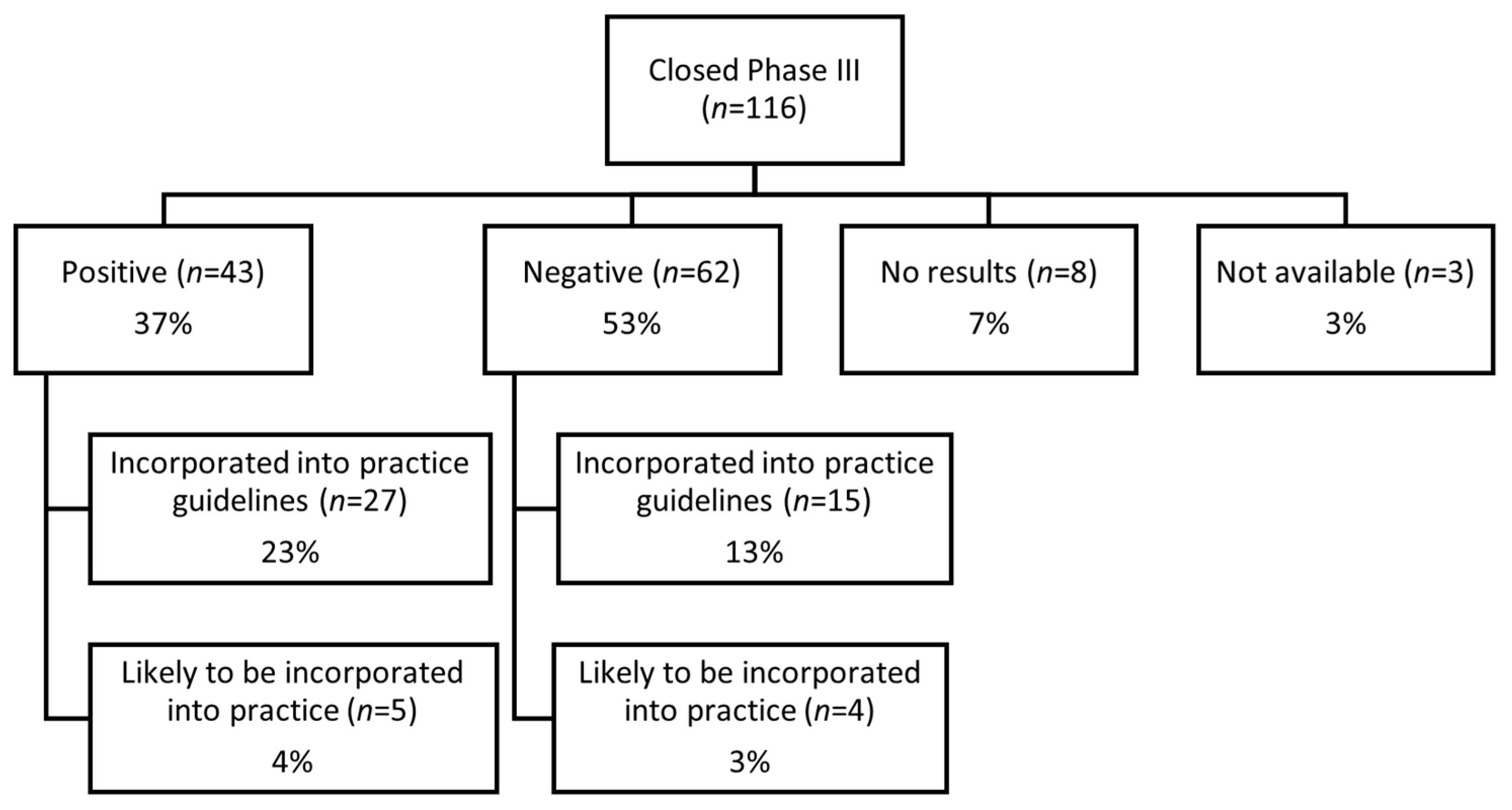

3.2.2. Practice Guideline Incorporation

3.2.3. Sponsorship and Practice-Changing Impact

3.3. Recruitment Contributions from Network Sites

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3CTN | Canadian Cancer Clinical Trials Network |

| ACCT | Academic Cancer Clinical Trials |

| ALL | Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia |

| ASCO | American Society of Clinical Oncology |

| ASTRO | American Society for Radiation Oncology |

| CCO | Cancer Care Ontario |

| CCTG | Canadian Cancer Trials Group |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| COG | Children’s Oncology Group |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| CMA | Canadian Medical Association |

| DSMB | Data Safety Monitoring Board |

| EANM | European Association of Nuclear Medicine |

| ESMO | European Society for Medical Oncology |

| GU | Genitourinary |

| ML-DS | Myeloid Leukemia of Down Syndrome |

| NCCN | National Comprehensive Cancer Network |

| OICR | Ontario Institute for Cancer Research |

| SIOPE | European Society for Paediatric Oncology |

| SNMMI | Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging |

Appendix A

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Study Results | |

| Positive | Results are reported in the literature and demonstrate a positive primary outcome: |

| |

| |

| Negative | Results are reported in the literature and demonstrate a negative primary outcome, meaning |

| |

| Inconclusive | Results were classified as inconclusive when the direction or significance of the primary outcome could not be determined from the available data, including cases where the study was prematurely terminated prior to reaching target accrual. |

| No Results Reported | Not available: No peer-reviewed results were found, and the primary study completion date is <24 months ago. |

| No results: No peer-reviewed results were found, and the primary study completion date is ≥24 months ago | |

| Pending final publication: No final, peer-reviewed results for the entire study population, but interim or subgroup results are available, or a peer-reviewed source explicitly states that results are pending or expected. | |

| Practice Changing | |

| Incorporated into Practice | Trials were considered incorporated if their results were cited as evidence supporting a North American or European guideline recommendation, regardless of whether the finding was positive or negative. If a trial was cited only to highlight its contribution to an unresolved clinical question or to support evidence from other studies, without informing a specific recommendation, it was not considered incorporated. |

| Likely to be Incorporated into Practice | The trial’s findings were not yet included in guideline updates or revisions, but a peer-reviewed source explicitly states that the results are informing clinical decisions, currently influencing practice, or are likely to be incorporated into clinical guidelines in the future. FDA or Health Canada approval often precedes or triggers guideline updates, so regulatory approval was considered a strong indicator of likely incorporation. |

| Other Key Terms | |

| Rare Cancers | Refers to adult cancer that occurs in <6 out of 100,000 people each year using the European standard; pediatric cancers occur in <2 out of 1,000,000 children each year. |

| Vulnerable Populations | Pediatric (<18), AYA (15–39), Elderly (>70) |

| Precision Medicine | Focuses on matching cancer treatments to the specific genetic and molecular features of a patient’s tumor, often using advanced testing to identify mutations or biomarkers that can be targeted by specific therapies. |

Oncology Guidelines Reviewed for Practice Change Assessment

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN)

- ○

- via both the JNCCN journal (https://jnccn.org).

- ○

- and the official NCCN guideline PDFs (https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls).

- American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO)

- ○

- ○

- and ASCO Publications (https://ascopubs.org) for joint or collaborative guidelines updates.

- American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) Guidelines

- European Society for Paediatric Oncology (SIOP Europe or SIOPE)

- International Childhood Liver Tumors Strategy Group—for pediatric liver cancer

- Cancer Care Ontario (CCO)

- American Urological Association Guidelines

- European Association of Urology—for prostate and bladder cancer.

- European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology

- European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO)—for European oncology practice

- European Association of Neuro-Oncology—for neuro-oncology

- Canadian Medical Association (CMA)

- Trip Database-https://www.tripdatabase.com—aggregates global guidelines.

- EANM/SNMMI Joint Guidelines for trials involving diagnostic imaging. These guidelines are published by the European Association of Nuclear Medicine and the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging.

- The American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy Practice Guidelines

- Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons—GI Surgery for all GI Surgeons

- Note: Searches will include both full guideline documents and peer-reviewed guideline updates to ensure that trials cited in collaborative or journal-based recommendations (e.g., ASCO–CCO updates, JNCCN articles) are captured. In the case of multiple guidelines being mentioned, we will cite the primary North American guidelines, such as NCCN, ASCO, and ASTRO.

| Reasons Cited for Termination | Phase I | Phase II | Phase III | Phase IV | Grand Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug company decision | 2 | 1 | 3 | ||

| DSMB review | 1 | 1 | |||

| Lack of funding | 1 | 1 | |||

| Negative study | 2 | 2 | |||

| Poor accrual | 3 | 14 | 1 | 1 | 19 |

| Staffing issues | 1 | 1 | |||

| Unacceptable Toxicity | 1 | 1 | |||

| Unknown | 2 | 2 | |||

| COVID-19 pandemic | 1 | 1 | |||

| Total | 3 | 22 | 4 | 2 | 31 |

| Trial Characteristics | Analysis | Phase III | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of trials | N | 116 | 350 |

| Study Phase | I | - | 29 (8%) |

| II | - | 196 (56%) | |

| III | 116 | 116 (33%) | |

| IV | - | 9 (3%) | |

| Disease Site | Bone | 1 (1%) | 5 (1%) |

| Brain/CNS | 8 (7%) | 19 (5%) | |

| Breast | 16 (14%) | 49 (14%) | |

| Gastrointestinal | 11 (9%) | 32 (9%) | |

| Genito-Urinary | 17 (15%) | 56 (16%) | |

| Gynecological | 12 (10%) | 25 (7%) | |

| Head and neck | 3 (3%) | 11 (3%) | |

| Hematology | 23 (20%) | 55 (16%) | |

| Lung | 10 (9%) | 32 (9%) | |

| Neuroblastoma | 1 (1%) | 7 (2%) | |

| Other | 9 (8%) | 43 (12%) | |

| Sarcoma | 4 (3%) | 9 (3%) | |

| Skin/Melanoma | 1 (1%) | 7 (2%) | |

| Country of Sponsor | Canada | 33 (28%) | 192 (55%) |

| United States | 71 (61%) | 142 (41%) | |

| Other | 13 (11%) | 16 (5%) | |

| Sponsor | NCI (USA) | 67 (58%) | 123 (35%) |

| CCTG | 39 (33%) | 87 (25%) | |

| COG | 21 (6%) | 41 (12%) | |

| Special Interest | Lifestyle interventions | 4 (3%) | 10 (3%) |

| Novel therapy | 9 (8%) | 69 (20%) | |

| Rare cancer setting | 39 (33%) | 109 (31%) | |

| Vulnerable populations | 26 (22%) | 71 (20%) | |

| Precision medicine | 80 (68%) | 80 (23%) | |

| Interventions | Behavioral | 3 (3%) | 13 (4%) |

| Drug | 75 (64%) | 232 (66%) | |

| Device | 3 (3%) | 8 (2%) | |

| Radiation | 39 (33%) | 82 (23%) | |

| Procedure | 0 (0%) | 58 (17%) | |

| Biological | 24 (21%) | 51 (15%) | |

| Type of Design | Basket Trial | 0 | 2 |

| Platform Trial | 1 | 5 | |

| Umbrella Trial | 0 | 1 | |

| Low-complexity method | 1 | 5 | |

| Multiple steps | 13 | 22 | |

| Completion status | Closed to recruitment | 60 (52%) | 129 (37%) |

| Completed | 52 (45%) | 190 (54%) | |

| Prematurely completed (terminated or withdrawn) | 4 (3%) | 31 (9%) |

| Trial | Practice-Defining Trial Outcome | Disease Site | Active Recruitment | NCT Number | Recruitment Contribution (%) | Publication | Practice Guidelines Changed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NRG-CC001 | Recommended HA-WBRT plus memantine to reduce neurocognitive decline in patients with brain metastases. | Brain Metastases | 2016–2018 | NCT02360215 | 8.9% (46/518) | [24] | NCCN [25] |

| (CCTG) MA.36/Olympia | Adjuvant Olaparib is recommended for HER2-negative, BRCA-mutated early breast cancer with residual disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, based on Olympia trial results. FDA approves Olaparib for adjuvant treatment of high-risk early breast cancer. | Breast | 2015–2019 | NCT02032823 | 1.9% (35/1837) | [26] | NCCN [27] |

| OCOG-2016-PETABC | The PETABC trial supported the guideline recommendation for using 18F-FDG PET/CT in staging stage IIB–III breast cancer, showing improved detection of stage IV disease and influencing treatment decisions. | Breast | 2016–2022 | NCT02751710 | 100% (369/369) | [28] | EJNMMI [29] |

| (CCTG) MA.37/PALLAS | The PALLAS trial showed no benefit of adjuvant Palbociclib, leading to guideline recommendations against its use in early breast cancer. | Breast | 2017–2025 | NCT02513394 | 2.6% (152/5796) | [30] | NCCN [31] |

| (EORTC) 1333-GUCG/PEACE III | Combining radium-223 with Enzalutamide for mCRPC showed improved progression-free survival and potential overall survival benefit. | GU/Prostate | 2018–2023 | NCT02194842 | 4.5% (20/446) | [32] | NCCN [33] |

| GOG–0275 | For low-risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia, supportive methotrexate and actinomycin-D are effective first-line single-agent therapies. | Gyne/Gestational Trophoblastic | 2015–2017 | NCT01535053 | 3.5% (2/57) | [34] | NCCN [35] |

| (CCTG) ENC.1/NRG-GY018 / MK-3475-868 | Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy as a new standard for advanced or recurrent endometrial cancer, regardless of mismatch repair status, led to FDA approval and guideline inclusion. | Gyne/Endometrial | 2021–2022 | NCT03914612 | 3.7% (30/813) | [36] | NCCN [37] |

| (CCTG) CLC.2/Alliance A041202 | Ibrutinib was superior to BendamustineB–rituximab for older patients with untreated CLL, supporting guideline recommendations and FDA-approved frontline use. | Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) | 2015–2016 | NCT01886872 | 7.9% (43/547) | [38] | NCCN [39] |

| (COG) AHOD1331 | Use of Brentuximab Vedotin with AVE-PC for high-risk pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma showed superior efficacy and reduced need for radiation. | Hodgkin lymphoma | 2015–2019 | NCT02166463 | 6.5% (39/600) | [40] | NCCN [41] |

| (COG) AALL1331 | For relapsed pediatric B-ALL, Blinatumomab was a treatment option despite early trial termination and no significant difference in disease-free survival. | B-ALL | 2015–2019 | NCT02101853 | 7.9% (53/669) | [42] | NCCN [43] |

| (COG) AAML1531 | For ML-DS, supporting risk-based treatment and use of HD-AraC to improve outcomes in standard-risk patients. | ML-DS | 2016–2022 | NCT02521493 | 5.4% (15/280) | [44] | SIOP Europe [45] |

| (CCTG) ALC.4 (ECOG E1910) | Adding Blinatumomab to consolidation chemotherapy for newly diagnosed B-lineage ALL, improving overall survival, and establishing a new standard for BCR::ABL1-negative patients. | ALL | 2017–2019 | NCT02003222 | 1.8% (9/488) | [46] | NCCN [47] |

| (CCTG) HDC.1/SWOG S1826 | Nivolumab + AVD as first-line treatment for advanced-stage Hodgkin lymphoma, showing better progression-free survival than BV + AVD; now a Category 1 recommendation in NCCN guidelines. | Hodgkin Lymphoma | 2021–2022 | NCT03907488 | 1.8% (18/994) | [48] | NCCN [49] |

| (EORTC) STRASS | There is no overall benefit of preoperative radiotherapy for retroperitoneal sarcoma, but it is supported for selective use in Liposarcoma. | Sarcoma | 2015–2017 | NCT01344018 | 4.5% (12/266) | [50] | NCCN [51] |

| (CCTG) SRC.7/Alliance A091105 | Sorafenib significantly improved progression-free survival in desmoid tumors and is now recommended in NCCN guidelines as a systemic therapy option. | Sarcoma | 2015–2016 | NCT02066181 | 5.7% (5/87) | [52] | NCCN [51] |

| (CCTG) SC.24 | The SC.24 trial showed stereotactic body radiotherapy improved pain control over conventional radiotherapy for spinal metastases; it is cited in Ontario guidelines for spine SBRT planning and delivery. | Spinal Metastases | 2015–2019 | NCT02512965 | 76.4% (175/229) | [53] | CCO [54] |

References

- Nass, S.J.; Moses, H.L.; Mendelsohn, J. (Eds.) Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Cancer Clinical Trials and the NCI Cooperative Group Program. In A National Cancer Clinical Trials System for the 21st Century: Reinvigorating the NCI Cooperative Group Program; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Cancer Research Alliance. Report on the State of Cancer Clinical Trials in Canada; Canadian Cancer Research Alliance: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2011. Available online: https://www.ccra-acrc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Clinical_Trials_Report_2011.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Schilsky, R.L. Publicly Funded Clinical Trials and the Future of Cancer Care. Ncologist 2013, 18, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unger, J.M.; Nghiem, V.T.; Hershman, D.L.; Vaidya, R.; LeBlanc, M.; Blanke, C.D. Association of National Cancer Institute–Sponsored Clinical Trial Network Group Studies with Guideline Care and New Drug Indications. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e1910593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, P.A.; Pater, J.; Thiessen, M.H.; Lee-Ying, R.M.; Monzon, J.G.; Cheung, W.Y. Impact of Canadian Cancer Trials Group (CCTG) phase III trials (P3Ts). J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, e18901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennette, C.S.; Ramsey, S.D.; McDermott, C.L.; Carlson, J.J.; Basu, A.; Veenstra, D.L. Predicting Low Accrual in the National Cancer Institute’s Cooperative Group Clinical Trials. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2015, 108, djv324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauck, C.L.; Kelechi, T.J.; Cartmell, K.B.; Mueller, M. Trial-level factors affecting accrual and completion of oncology clinical trials: A systematic review. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 2021, 24, 100843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seruga, B.; Sadikov, A.; Cazap, E.L.; Delgado, L.B.; Digumarti, R.; Leighl, N.B.; Meshref, M.M.; Minami, H.; Robinson, E.; Yamaguchi, N.H.; et al. Barriers and Challenges to Global Clinical Cancer Research. Ncologist 2013, 19, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, C.; Sundquist, S.; Dancey, J.; Peacock, S. Barriers to Conducting Cancer Trials in Canada: An Analysis of Key Informant Interviews. Curr. Oncol. 2020, 27, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Cancer Clinical Trials Network. Portfolio Assessment. Available online: https://3ctn.ca/for-researchers/trial-portfolio/portfolio-assessment/ (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Smalheiser, N.R.; Holt, A.W. A web-based tool for automatically linking clinical trials to their publications. J. Am. Med Inform. Assoc. 2022, 29, 822–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoales, J.; Xu, R.; Kato, D.; Sundquist, S.; Pater, J.L.; Dancey, J. A novel and comprehensive framework for categorizing and evaluating the potential impact of academic cancer clinical trials [Poster Presentation]. In Proceedings of the 2019 Canadian Cancer Research Conference, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2–3 November 2019; Available online: https://3ctn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/3CTN-CCRC-Poster-Portfolio-Impact-Final.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Elimova, E.; Moignard, S.; Li, X.; Yu, M.; Xu, W.; Seruga, B.; Tannock, I.F. Updating Reports of Phase 3 Clinical Trials for Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2021, 7, 593–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra-Majumdar, M.; Kesselheim, A.S. Reporting bias in clinical trials: Progress toward transparency and next steps. PLoS Med. 2022, 19, e1003894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwan, K.; Altman, D.G.; Arnaiz, J.A.; Bloom, J.; Chan, A.-W.; Cronin, E.; Decullier, E.; Easterbrook, P.J.; Von Elm, E.; Gamble, C.; et al. Systematic Review of the Empirical Evidence of Study Publication Bias and Outcome Reporting Bias. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Showell, M.G.; Cole, S.; Clarke, M.J.; DeVito, N.J.; Farquhar, C.; Jordan, V. Time to publication for results of clinical trials. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024, 11, MR000011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioannidis, J.P.A. Effect of the Statistical Significance of Results on the Time to Completion and Publication of Randomized Efficacy Trials. JAMA 1998, 279, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Cancer Clinical Trials Network. Outcomes and Publication Search. Available online: https://3ctn.ca/outcomes-and-publication-search/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Dancey, J. Canada Needs a National System for Cancer Clinical Trials. Toronto Star. 19 February 2024. Available online: https://ctg.queensu.ca/bulletin/canada-needs-national-system-cancer-clinical-trials (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Joober, R.; Schmitz, N.; Annable, L.; Boksa, P. Publication bias: What are the challenges and can they be overcome? J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2012, 37, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickersin, K.; Chalmers, I. Recognizing, investigating and dealing with incomplete and biased reporting of clinical research: From Francis Bacon to the WHO. J. R. Soc. Med. 2011, 104, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laviolle, B.; Locher, C.; Allain, J.-S.; Le Cornu, Q.; Charpentier, P.; Lefebvre, M.; Le Pape, C.; Leven, C.; Palpacuer, C.; Pontoizeau, C.; et al. Trends of Publication of Negative Trials Over Time. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2025, 117, 818–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegra, C.J.; Goodwin, P.J.; Ganz, P.A. Can We Find the Positive in Negative Clinical Trials? JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2019, 111, 637–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.D.; Gondi, V.; Pugh, S.; Tome, W.A.; Wefel, J.S.; Armstrong, T.S.; Bovi, J.A.; Robinson, C.; Konski, A.; Khuntia, D.; et al. Hippocampal Avoidance During Whole-Brain Radiotherapy Plus Memantine for Patients with Brain Metastases: Phase III Trial NRG Oncology CC001. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 1019–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabors, L.B.; Portnow, J.; Ahluwalia, M.; Baehring, J.; Brem, H.; Brem, S.; Butowski, N.; Campian, J.L.; Clark, S.W.; Fabiano, A.J.; et al. Central Nervous System Cancers, Version 3.2020, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2020, 18, 1537–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutt, A.N.J.; Garber, J.E.; Kaufman, B.; Viale, G.; Fumagalli, D.; Rastogi, P.; Gelber, R.D.; de Azambuja, E.; Fielding, A.; Balmaña, J.; et al. Adjuvant Olaparib for Patients with BRCA1 - or BRCA2 -Mutated Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 2394–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) Breast Cancer. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Dayes, I.S.; Metser, U.; Hodgson, N.; Parpia, S.; Eisen, A.F.; George, R.; Blanchette, P.; Cil, T.D.; Arnaout, A.; Chan, A.; et al. Impact of 18F-Labeled Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography-Computed Tomography Versus Conventional Staging in Patients with Locally Advanced Breast Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 3909–3916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, S.C.; Woll, J.P.P.; Cardoso, F.; Groheux, D.; Cook, G.J.R.; Ulaner, G.A.; Jacene, H.; Rubio, I.T.; Schoones, J.W.; Peeters, M.-J.V.; et al. Joint EANM-SNMMI guideline on the role of 2-[18F]FDG PET/CT in no special type breast cancer. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 2024, 51, 2706–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnant, M.; Dueck, A.C.; Frantal, S.; Martin, M.; Burstein, H.J.; Greil, R.; Fox, P.; Wolff, A.C.; Chan, A.; Winer, E.P.; et al. Adjuvant Palbociclib for Early Breast Cancer: The PALLAS Trial Results (ABCSG-42/AFT-05/BIG-14-03). J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giordano, S.H.; Elias, A.D.; Gradishar, W.J. NCCN Guidelines Updates: Breast Cancer. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2018, 16, 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillessen, S.; Choudhury, A.; Saad, F.; Gallardo, E.; Soares, A.; Loriot, Y.; McDermott, R.; Rodriguez-Vida, A.; Isaacson, P.; Nolè, F.; et al. LBA1 A randomized multicenter open label phase III trial comparing enzalutamide vs a combination of Radium-223 (Ra223) and enzalutamide in asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic patients with bone metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC): First results of EORTC-GUCG 1333/PEACE-3. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, S1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, E.M.; Srinivas, S.; Adra, N.; An, Y.; Barocas, D.; Bitting, R.; Bryce, A.; Chapin, B.; Cheng, H.H.; D’aMico, A.V.; et al. Prostate Cancer, Version 4.2023, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2023, 21, 1067–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schink, J.C.; Filiaci, V.; Huang, H.Q.; Tidy, J.; Winter, M.; Carter, J.; Anderson, N.; Moxley, K.; Yabuno, A.; Taylor, S.E.; et al. An international randomized phase III trial of pulse actinomycin-D versus multi-day methotrexate for the treatment of low risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia; NRG/GOG 275. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020, 158, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Rustum, N.R.; Yashar, C.M.; Bean, S.; Bradley, K.; Campos, S.M.; Chon, H.S.; Chu, C.; Cohn, D.; Crispens, M.A.; Damast, S.; et al. Gestational Trophoblastic Neoplasia, Version 2.2019, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2019, 17, 1374–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskander, R.N.; Sill, M.W.; Beffa, L.; Moore, R.G.; Hope, J.M.; Musa, F.B.; Mannel, R.; Shahin, M.S.; Cantuaria, G.H.; Girda, E.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Advanced Endometrial Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 2159–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Rustum, N.R.; Campos, S.M.; Amarnath, S.; Arend, R.; Barber, E.; Bradley, K.; Brooks, R.; Chino, J.; Chon, H.S.; Crispens, M.A.; et al. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Uterine Neoplasms, Version 3.2025: Featured Updates to the NCCN Guidelines®. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2025, 23, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woyach, J.A.; Ruppert, A.S.; Heerema, N.A.; Zhao, W.; Booth, A.M.; Ding, W.; Bartlett, N.L.; Brander, D.M.; Barr, P.M.; Rogers, K.A.; et al. Ibrutinib Regimens versus Chemoimmunotherapy in Older Patients with Untreated CLL. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2517–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wierda, W.G.; Brown, J.; Abramson, J.S.; Awan, F.; Bilgrami, S.F.; Bociek, G.; Brander, D.; Cortese, M.; Cripe, L.; Davis, R.S.; et al. Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia/Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma, Version 2.2024, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2024, 22, 175–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellino, S.M.; Pei, Q.; Parsons, S.K.; Hodgson, D.; McCarten, K.; Horton, T.; Cho, S.; Wu, Y.; Punnett, A.; Dave, H.; et al. Brentuximab Vedotin with Chemotherapy in Pediatric High-Risk Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 1649–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) Pediatric Hodgkin Lymphoma. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/ped_hodgkin.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Brown, P.A.; Ji, L.; Xu, X.; Devidas, M.; Hogan, L.E.; Borowitz, M.J.; Raetz, E.A.; Zugmaier, G.; Sharon, E.; Bernhardt, M.B.; et al. Effect of postreinduction therapy consolidation with blinatumomab vs chemotherapy on disease-free survival in children, adolescents, and young adults with first relapse of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2021, 325, 833–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/ped_all.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Hitzler, J.; Alonzo, T.; Gerbing, R.; Beckman, A.; Hirsch, B.; Raimondi, S.; Chisholm, K.; Viola, S.; Brodersen, L.; Loken, M.; et al. High-dose AraC is essential for the treatment of ML-DS independent of postinduction MRD: Results of the COG AAML1531 trial. Blood 2021, 138, 2337–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childhood Liver Tumors Strategy Group (SIOPEL). Standard Clinical Practice Recommendations for Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) in Children and Adolescents. Available online: https://siope.eu/media/documents/acute-myeloid-leukemia.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Litzow, M.R.; Sun, Z.; Paietta, E.; Mattison, R.J.; Lazarus, H.M.; Rowe, J.M.; Arber, D.A.; Mullighan, C.G.; Willman, C.L.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Consolidation Therapy with Blinatumomab Improves Overall Survival in Newly Diagnosed Adult Patients with B-Lineage Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in Measurable Residual Disease Negative Remission: Results from the ECOG-ACRIN E1910 Randomized Phase III National Cooperative Clinical Trials Network Trial. Blood 2022, 140, LBA-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/all.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Herrera, A.F.; LeBlanc, M.; Castellino, S.M.; Li, H.; Rutherford, S.C.; Evens, A.M.; Davison, K.; Punnett, A.; Parsons, S.K.; Ahmed, S.; et al. Nivolumab+AVD in Advanced-Stage Classic Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) Hodgkin Lymphoma. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/hodgkins.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Bonvalot, S.; Gronchi, A.; Le Pechoux, C.; Swallow, C.J.; Strauss, D.C.; Meeus, P.; van Coevorden, F.; Stoldt, S.; Stoeckle, E.; Rutkowski, P.; et al. STRASS (EORTC 62092): A phase III randomized study of preoperative radiotherapy plus surgery versus surgery alone for patients with retroperitoneal sarcoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 11001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Mehren, M.; Randall, R.L.; Benjamin, R.S.; Boles, S.; Bui, M.M.; Ganjoo, K.N.; George, S.; Gonzalez, R.J.; Heslin, M.J.; Kane, J.M.; et al. Soft Tissue Sarcoma, Version 2.2018, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2018, 16, 536–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gounder, M.M.; Mahoney, M.R.; Van Tine, B.A.; Ravi, V.; Attia, S.; Deshpande, H.A.; Gupta, A.A.; Milhem, M.; Conry, R.M.; Movva, S.; et al. Sorafenib for Advanced and Refractory Desmoid Tumors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2417–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahgal, A.; Myrehaug, S.D.; Siva, S.; Masucci, G.L.; Maralani, P.J.; Brundage, M.; Butler, J.; Chow, E.; Fehlings, M.G.; Foote, M.; et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy versus conventional external beam radiotherapy in patients with painful spinal metastases: An open-label, multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 1023–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahgal, A.; Kellett, S.; Nguyen, T.; Maralani, P.; Greenspoon, J.; Linden, K.; Pearce, A.; Siddiqi, F.; Ruschin, M. SBRT for Spine Expert Panel. Consensus-Based Organizational Guideline for the Planning and Delivery of Spine Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy Treatment in Ontario. Available online: https://www.cancercareontario.ca/en/file/81341/download?token=nDwH_nCo (accessed on 31 July 2025).

| Phase | All Trials | Reported in Registry | Journal Publication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I | 29 | 2 (7%) | 21 (72%) |

| Phase II | 196 | 79 (40%) | 148 (76%) |

| Phase III | 116 | 76 (66%) | 105 (91%) |

| Phase IV | 9 | 2 (22%) | 8 (89%) |

| Total | 350 | 159 (45%) | 282 (81%) |

| Year Trial Closed | Number of Trials | Sample Size | Global Recruitment * | 3CTN Sites Recruitment | 3CTN Sites Contribution (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 16 | 2930 | 2158 | 181 | 8% |

| 2016 | 28 | 4406 | 2894 | 836 | 29% |

| 2017 | 34 | 8861 | 7596 | 859 | 11% |

| 2018 | 42 | 14,873 | 14,231 | 3134 | 22% |

| 2019 | 41 | 14,536 | 16,554 | 2595 | 16% |

| 2020 | 44 | 20,217 | 20,458 | 2962 | 14% |

| 2021 | 39 | 11,886 | 11,221 | 2312 | 21% |

| 2022 | 34 | 25,381 | 18,903 | 2894 | 15% |

| 2023 | 40 | 18,777 | 17,821 | 2521 | 14% |

| 2024 | 32 | 11,553 | 8223 | 2681 | 33% |

| Total | 350 | 133,420 | 120,059 | 20,975 | 17% |

| Median | 36.5 | 13,211 | 12,726 | 2558 | 15% |

| IQR | 8.25 | 8267 | 9751.5 | 1618.5 | 7% |

| Study Results | Number of Trials | Global Recruitment | 3CTN Sites Recruitment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | 62 (53%) | 52,999 | 3763 (7%) |

| No results | 8 (7%) | 1500 | 355 (24%) |

| Not available | 3 (3%) | 385 | 139 (36%) |

| Positive | 43 (37%) | 37,679 | 3771 (10%) |

| Total | 116 | 92,563 | 8028 (9%) |

| Study Results | Number of Trials * | Global Recruitment | 3CTN Sites Recruitment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | 15 | 211,518 | 958 (4.5%) |

| Positive | 28 | 32,826 | 2593 (7.1%) |

| Total | 43 | 54,007 | 3551 (6.6%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, R.Y.; Kato, D.; Percival, V.; Schoales, J.; Sundquist, S.; Chowdhury, R.; Pond, G.R.; Dancey, J.E. The Outcome and Impact of Academic Cancer Clinical Trials with Participation from Canadian Sites (2015–2024). Cancers 2025, 17, 4009. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17244009

Xu RY, Kato D, Percival V, Schoales J, Sundquist S, Chowdhury R, Pond GR, Dancey JE. The Outcome and Impact of Academic Cancer Clinical Trials with Participation from Canadian Sites (2015–2024). Cancers. 2025; 17(24):4009. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17244009

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Rebecca Y., Diana Kato, Victoria Percival, James Schoales, Stephen Sundquist, Raisa Chowdhury, Gregory R. Pond, and Janet E. Dancey. 2025. "The Outcome and Impact of Academic Cancer Clinical Trials with Participation from Canadian Sites (2015–2024)" Cancers 17, no. 24: 4009. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17244009

APA StyleXu, R. Y., Kato, D., Percival, V., Schoales, J., Sundquist, S., Chowdhury, R., Pond, G. R., & Dancey, J. E. (2025). The Outcome and Impact of Academic Cancer Clinical Trials with Participation from Canadian Sites (2015–2024). Cancers, 17(24), 4009. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17244009