Early BCR::ABL1 Reduction as a Predictor of Deep Molecular Response in Pediatric Chronic-Phase Chronic Myeloid Leukemia

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Treatment

2.3. Molecular Analysis and Assessment of Treatment Response

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient and Baseline Characteristics

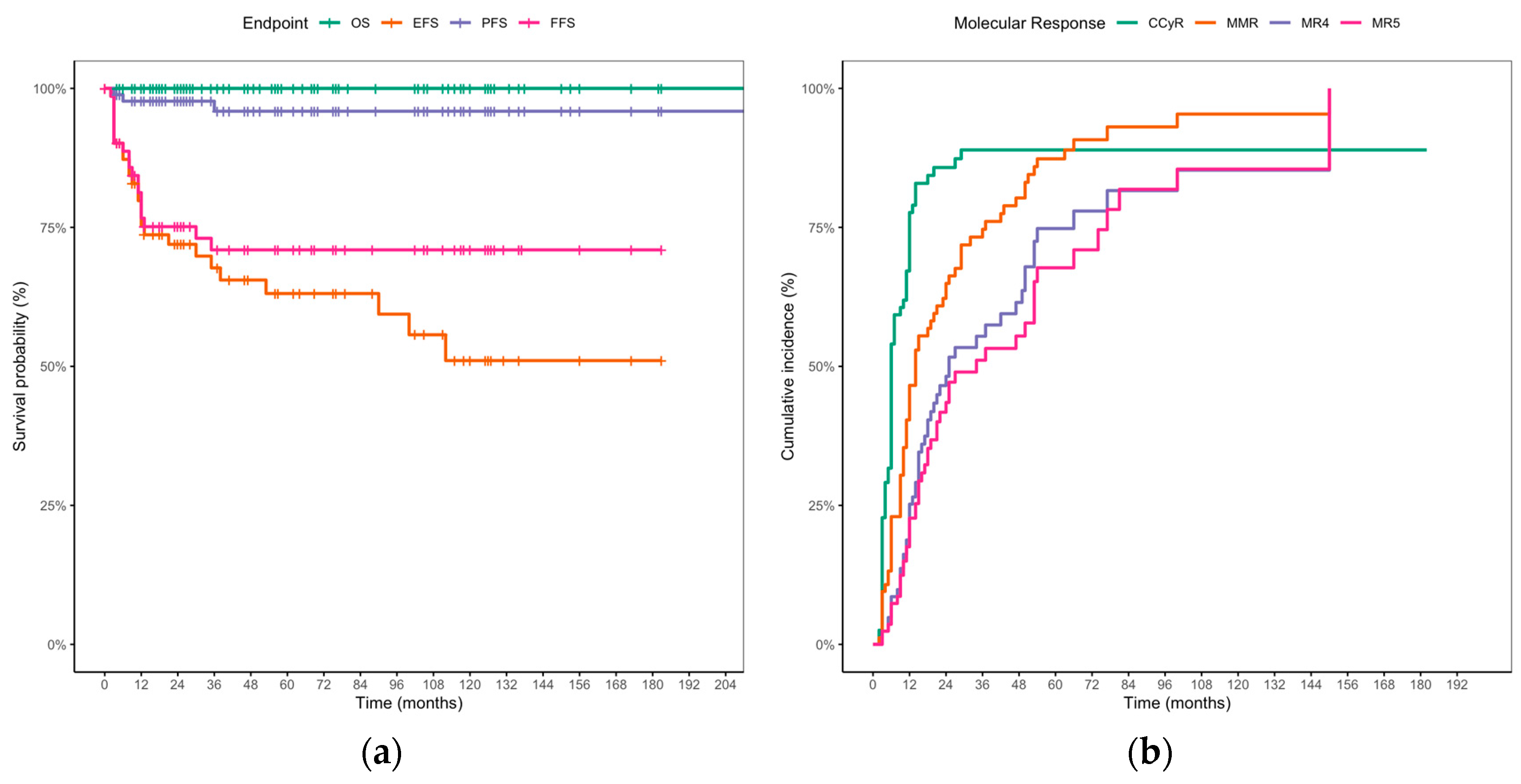

3.2. TKI Treatment, Response Milestones, and Long-Term Outcomes

3.3. Prognostic Impact of 3-Month Molecular Response on MMR and DMR

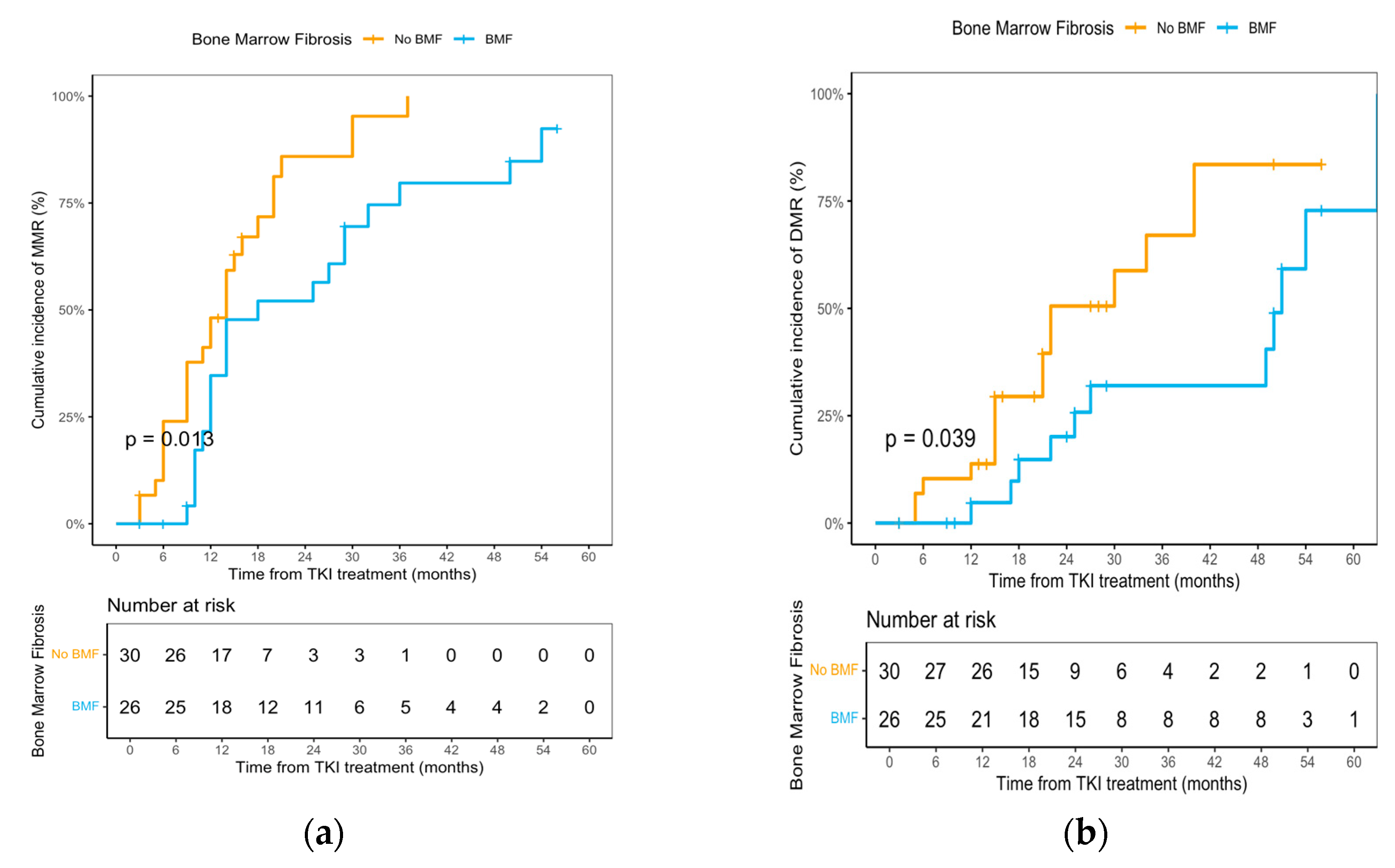

3.4. Bone Marrow Fibrosis and Genomic Correlates

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CML | Chronic myeloid leukemia |

| TKI | Tyrosine kinase inhibitor |

| EMR | Early molecular response |

| MMR | Major molecular response |

| DMR | Deep molecular remission |

| TFR | Treatment-free remission |

| ELN | European Leukemia Net |

| ELTS | EUTOS long-term survival |

| BMF | Bone marrow fibrosis |

| ACA | Additional chromosomal abnormality |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| IS | International Scale |

| WBC | White blood cell |

| CHR | Complete hematologic response |

| CCyR | Complete cytogenetic response |

| Ph+ | Philadelphia chromosome–positive |

| OS | Overall survival |

| PFS | Progression-free survival |

| EFS | Event-free survival |

| FFS | Failure-free survival |

| AP | Accelerated phase |

| BP | Blast phase |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| HSCT | Hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation |

| MR4 | Molecular response 4 |

| MR4.5 | Molecular response 4.5 |

| MR5 | Molecular response 5 |

References

- Athale, U.; Hijiya, N.; Patterson, B.C.; Bergsagel, J.; Andolina, J.R.; Bittencourt, H.; Schultz, K.R.; Burke, M.J.; Redell, M.S.; Kolb, E.A.; et al. Management of chronic myeloid leukemia in children and adolescents: Recommendations from the Children’s Oncology Group CML Working Group. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2019, 66, e27827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijiya, N.; Suttorp, M. How I treat chronic myeloid leukemia in children and adolescents. Blood 2019, 133, 2374–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijiya, N.; Schultz, K.R.; Metzler, M.; Millot, F.; Suttorp, M. Pediatric chronic myeloid leukemia is a unique disease that requires a different approach. Blood 2016, 127, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ries, L.A.G.; Smith, M.A.; Gurney, J.G.; Linet, M.; Tamra, T.; Young, J.L.; Bunin, G.R. (Eds.) Cancer Incidence and Survival Among Children and Adolescents: United States SEER Program 1975–1995; SEER Program; National Cancer Institute: Bethesda, MD, USA, 1999; Volume 99, pp. 46–49. [Google Scholar]

- Shima, H.; Tokuyama, M.; Tanizawa, A.; Tono, C.; Hamamoto, K.; Muramatsu, H.; Watanabe, A.; Hotta, N.; Ito, M.; Kurosawa, H.; et al. Distinct impact of imatinib on growth at prepubertal and pubertal ages of children with chronic myeloid leukemia. J. Pediatr. 2011, 159, 676–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millot, F.; Guilhot, J.; Baruchel, A.; Petit, A.; Leblanc, T.; Bertrand, Y.; Mazingue, F.; Lutz, P.; Vérité, C.; Berthou, C.; et al. Growth deceleration in children treated with imatinib for chronic myeloid leukaemia. Eur. J. Cancer 2014, 50, 3206–3211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochhaus, A.; Baccarani, M.; Silver, R.T.; Schiffer, C.; Apperley, J.F.; Cervantes, F.; Clark, R.E.; Cortes, J.E.; Deininger, M.W.; Guilhot, F.; et al. European LeukemiaNet 2020 recommendations for treating chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2020, 34, 966–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millot, F.; Ampatzidou, M.; Moulik, N.R.; Tewari, S.; Elhaddad, A.; Hammad, M.; Pichler, H.; Lion, T.; Tragiannidis, A.; Shima, H.; et al. Management of children and adolescents with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase: International pediatric chronic myeloid leukemia expert panel recommendations. Leukemia 2025, 39, 779–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, D.; Ibrahim, A.R.; Lucas, C.; Gerrard, G.; Wang, L.; Szydlo, R.M.; Clark, R.E.; Apperley, J.F.; Milojkovic, D.; Bua, M.; et al. Assessment of BCR-ABL1 transcript levels at 3 months is the only requirement for predicting outcome for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, T.P.; Saglio, G.; Kantarjian, H.M.; Guilhot, F.; Niederwieser, D.; Rosti, G.; Nakaseko, C.; De Souza, C.A.; Kalaycio, M.E.; Meier, S.; et al. Early molecular response predicts outcomes in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase treated with frontline nilotinib or imatinib. Blood 2014, 123, 1353–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanfstein, B.; Müller, M.C.; Hehlmann, R.; Erben, P.; Lauseker, M.; Fabarius, A.; Schnittger, S.; Haferlach, C.; Göhring, G.; Proetel, U.; et al. Early molecular and cytogenetic response is predictive for long-term progression-free and overall survival in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). Leukemia 2012, 26, 2096–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millot, F.; Guilhot, J.; Baruchel, A.; Petit, A.; Bertrand, Y.; Mazingue, F.; Lutz, P.; Vérité, C.; Berthou, C.; Galambrun, C.; et al. Impact of early molecular response in children with chronic myeloid leukemia treated in the French Glivec phase 4 study. Blood 2014, 124, 2408–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Branford, S.; Yeung, D.T.; Parker, W.T.; Roberts, N.D.; Purins, L.; Braley, J.A.; Altamura, H.K.; Yeoman, A.L.; Georgievski, J.; Jamison, B.A.; et al. Prognosis for patients with CML and >10% BCR-ABL1 after 3 months of imatinib depends on the rate of BCR-ABL1 decline. Blood 2014, 124, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmuganathan, N.; Pagani, I.S.; Ross, D.M.; Park, S.; Yong, A.S.M.; Braley, J.A.; Altamura, H.K.; Hiwase, D.K.; Yeung, D.T.; Kim, D.W.; et al. Early BCR-ABL1 kinetics are predictive of subsequent achievement of treatment-free remission in chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood 2021, 137, 1196–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iriyama, N.; Fujisawa, S.; Yoshida, C.; Wakita, H.; Chiba, S.; Okamoto, S.; Kawakami, K.; Takezako, N.; Kumagai, T.; Inokuchi, K.; et al. Shorter halving time of BCR-ABL1 transcripts is a novel predictor for achievement of molecular responses in newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia treated with dasatinib: Results of the D-first study of Kanto CML study group. Am. J. Hematol. 2015, 90, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fava, C.; Rege-Cambrin, G.; Dogliotti, I.; Gottardi, E.; Berchialla, P.; Di Gioacchino, B.; Crasto, F.; Lorenzatti, R.; Volpengo, A.; Daraio, F.; et al. Early BCR-ABL1 reduction is predictive of better event-free survival in patients with newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia treated with any tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2016, 16, S96–S100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennisi, M.S.; Stella, S.; Vitale, S.R.; Puma, A.; Di Gregorio, S.; Romano, C.; Tirrò, E.; Massimino, M.; Antolino, A.; Siragusa, S.; et al. BCR-ABL1 doubling-times and halving-times may predict CML response to tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Jia, X.; Zi, J.; Song, H.; Wang, S.; McGrath, M.; Zhao, L.; Song, C.; Ge, Z. BCR-ABL1 transcript decline ratio combined BCR-ABL1IS as a precise predictor for imatinib response and outcome in the patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. J. Cancer 2020, 11, 2234–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shima, H.; Kada, A.; Tanizawa, A.; Sato, I.; Tono, C.; Ito, M.; Yuza, Y.; Watanabe, A.; Kamibeppu, K.; Uryu, H.; et al. Discontinuation of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in pediatric chronic myeloid leukemia. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2022, 69, e29699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millot, F.; Suttorp, M.; Ragot, S.; Leverger, G.; Dalle, J.H.; Thomas, C.; Cheikh, N.; Nelken, B.; Poirée, M.; Plat, G.; et al. Discontinuation of imatinib in children with chronic myeloid leukemia: A study from the international registry of childhood CML. Cancers 2021, 13, 4102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, D.; Trivedi, M.; Doctor, C.; Parikh, B.; Panchal, H.P.; Yadav, R. Impact of Molecular and Cytogenetic Responses on Long-Term Outcomes in Children and Adolescents with Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: A Retrospective Study from India. Cureus 2025, 17, e89359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stella, S.; Zammit, V.; Vitale, S.R.; Pennisi, M.S.; Massimino, M.; Tirrò, E.; Forte, S.; Spitaleri, A.; Antolino, A.; Siracusa, S.; et al. Clinical Implications of Discordant Early Molecular Responses in CML Patients Treated with Imatinib. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narlı Özdemir, Z.; Kılıçaslan, N.A.; Yılmaz, M.; Eşkazan, A.E. Guidelines for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia from the NCCN and ELN: Differences and similarities. Int. J. Hematol. 2023, 117, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baccarani, M.; Cortes, J.; Pane, F.; Niederwieser, D.; Saglio, G.; Apperley, J.; Cervantes, F.; Deininger, M.; Gratwohl, A.; Guilhot, F.; et al. Chronic myeloid leukemia: An update of concepts and management recommendations of European LeukemiaNet. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 6041–6051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccarani, M.; Deininger, M.W.; Rosti, G.; Hochhaus, A.; Soverini, S.; Apperley, J.F.; Cervantes, F.; Clark, R.E.; Cortes, J.E.; Guilhot, F.; et al. European LeukemiaNet recommendations for the management of chronic myeloid leukemia: 2013. Blood 2013, 122, 872–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccarani, M.; Saglio, G.; Goldman, J.; Hochhaus, A.; Simonsson, B.; Appelbaum, F.; Apperley, J.; Cervantes, F.; Cortes, J.; Deininger, M.; et al. Evolving concepts in the management of chronic myeloid leukemia: Recommendations from an expert panel on behalf of the European LeukemiaNet. Blood 2006, 108, 1809–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dongen, J.J.; Macintyre, E.A.; Gabert, J.A.; Delabesse, E.; Rossi, V.; Saglio, G.; Gottardi, E.; Rambaldi, A.; Dotti, G.; Griesinger, F.; et al. Standardized RT-PCR analysis of fusion gene transcripts from chromosome aberrations in acute leukemia for detection of minimal residual disease. Report of the BIOMED-1 Concerted Action: Investigation of minimal residual disease in acute leukemia. Leukemia 1999, 13, 1901–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beillard, E.; Pallisgaard, N.; van der Velden, V.H.; Bi, W.; Dee, R.; van der Schoot, E.; Delabesse, E.; Macintyre, E.; Gottardi, E.; Saglio, G.; et al. Evaluation of candidate control genes for diagnosis and residual disease detection in leukemic patients using ‘real-time’ quantitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RQ-PCR)—A Europe against cancer program. Leukemia 2003, 17, 2474–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, H.E.; Salmon, M.; Albano, F.; Andersen, C.S.A.; Balabanov, S.; Balatzenko, G.; Barbany, G.; Cayuela, J.M.; Cerveira, N.; Cochaux, P.; et al. Standardization of molecular monitoring of CML: Results and recommendations from the European treatment and outcome study. Leukemia 2022, 36, 1834–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfirrmann, M.; Baccarani, M.; Saussele, S.; Guilhot, J.; Cervantes, F.; Ossenkoppele, G.; Hoffmann, V.S.; Castagnetti, F.; Hasford, J.; Hehlmann, R.; et al. Prognosis of long-term survival considering disease-specific death in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2016, 30, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, K.; Shome, D.K.; Kulkarni, B.; Ghosh, M.K.; Ghosh, K. Fibrosis and bone marrow: Understanding causation and pathobiology. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millot, F.; Guilhot, J.; Suttorp, M.; Güneş, A.M.; Sedlacek, P.; De Bont, E.; Li, C.K.; Kalwak, K.; Lausen, B.; Culic, S.; et al. Prognostic discrimination based on the EUTOS long-term survival score within the International Registry for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia in children and adolescents. Haematologica 2017, 102, 1704–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganguly, S.; Pushpam, D.; Mian, A.; Chopra, A.; Gupta, R.; Bakhshi, S. Real-world Experience of Imatinib in Pediatric Chronic Phase Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: A Single-center Experience from India. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020, 20, e437–e444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janeczko-Czarnecka, M.; Krawczuk-Rybak, M.; Karpińska-Derda, I.; Niedźwiecki, M.; Musioł, K.; Ćwiklińska, M.; Drabko, K.; Mycko, K.; Ociepa, T.; Pawelec, K.; et al. Imatinib in the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia in children and adolescents is effective and well tolerated: Report of the Polish Pediatric Study Group for the Treatment of Leukemias and Lymphomas. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2018, 27, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branford, S.; Kim, D.W.; Soverini, S.; Haque, A.; Shou, Y.; Woodman, R.C.; Kantarjian, H.M.; Martinelli, G.; Radich, J.P.; Saglio, G.; et al. Initial molecular response at 3 months may predict both response and event-free survival at 24 months in imatinib-resistant or -intolerant patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase treated with nilotinib. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 4323–4329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.C.; Kuo, M.C.; Wu, K.H.; Chen, T.Y.; Chen, J.S.; Wang, M.C.; Lin, T.L.; Yang, Y.; Ma, M.C.; Wang, P.N.; et al. Children with chronic myeloid leukaemia treated with front-line imatinib have a slower molecular response and comparable survival compared with adults: A multicenter experience in Taiwan. Br. J. Cancer 2023, 128, 1294–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Hu, J.; Chen, S.; Jin, J.; Liu, T.; Zhou, J.; Hu, Y.; Ma, D.; et al. Early BCR-ABL1 decline in imatinib-treated patients with chronic myeloid leukemia: Results from a multicenter study of the Chinese CML alliance. Blood Cancer J. 2018, 8, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millot, F.; Baruchel, A.; Guilhot, J.; Petit, A.; Leblanc, T.; Bertrand, Y.; Mazingue, F.; Lutz, P.; Vérité, C.; Berthou, C.; et al. Imatinib is effective in children with previously untreated chronic myelogenous leukemia in early chronic phase: Results of the French national phase IV trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 2827–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saugues, S.; Lambert, C.; Daguenet, E.; Roth-Guepin, G.; Huguet, F.; Cony-Makhoul, P.; Ansah, H.J.; Escoffre-Barbe, M.; Turhan, A.; Rousselot, P.; et al. The initial molecular response predicts the deep molecular response but not treatment-free remission maintenance in a real-world chronic myeloid leukemia cohort. Haematologica 2024, 109, 2893–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.S.; Gale, R.P.; Huang, X.J.; Jiang, Q. Is the Sokal or EUTOS long-term survival (ELTS) score a better predictor of responses and outcomes in persons with chronic myeloid leukemia receiving tyrosine-kinase inhibitors? Leukemia 2022, 36, 482–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buesche, G.; Ganser, A.; Schlegelberger, B.; von Neuhoff, N.; Gadzicki, D.; Hecker, H.; Bock, O.; Frye, B.; Kreipe, H. Marrow fibrosis and its relevance during imatinib treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2007, 21, 2420–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, T.; Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wu, D.; Feng, W.; Lu, Y.; Zhu, X.; Liu, L.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, L.; et al. Myelofibrosis predicts deep molecular response 4.5 in chronic myeloid leukaemia patients initially treated with imatinib: An extensive, multicenter and retrospective study to develop a prognostic model. Clin. Transl. Med. 2024, 14, e70101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pepeler, M.S.; Tıglıoglu, M.; Dagdas, S.; Ozhamamcıoglu, E.; Han, U.; Albayrak, A.; Aydın, M.S.; Korkmaz, G.; Pamukcuoğlu, M.; Ceran, F.; et al. Prognostic Impact of Bone Marrow Fibrosis and Effects of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors on Bone Marrow Fibrosis in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2024, 24, e161–e167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrens, Y.L.; Gaschler, L.; Nienhold, R.; Reinkens, T.; Schirmer, E.; Knöß, S.; Strasser, R.; Sembill, S.; Wotschofsky, Z.; Suttorp, M.; et al. Somatic variant profiling in chronic phase pediatric chronic myeloid leukemia. Haematologica 2024, 109, 942–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schönfeld, L.; Rinke, J.; Hinze, A.; Nagel, S.N.; Schäfer, V.; Schenk, T.; Fabisch, C.; Brümmendorf, T.H.; Burchert, A.; le Coutre, P.; et al. ASXL1 mutations predict inferior molecular response to nilotinib treatment in chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2022, 36, 2242–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years, median (range) | 9.2 (1.0–17.0) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 64 (72.7) |

| Female | 24 (27.3) |

| Leukocyte count × 109/L, median (range) | 156.8 (23.9–709.6) |

| Platelet count × 109/L, median (range) | 529 (187–3369) |

| Hemoglobin, g/L, median (range) | 98 (61–151) |

| Blood basophils, %, median (range) | 4 (0–12) |

| Symptoms at diagnosis | |

| Fatigue | 24 (27.3) |

| Fever | 28 (31.8) |

| Bleeding tendencies | 9 (10.2) |

| Abdominal distension/discomfort | 17 (19.3) |

| Weight loss | 8 (9.1) |

| Asymptomatic | 25 (28.4) |

| Bone pain | 8 (9.1) |

| Priapism | 2(2.3) |

| Clinical signs at diagnosis | |

| Hepatomegaly | 25 (28.4) |

| Splenomegaly | 61 (69.3) |

| Spleen size below costal margin, cm, median (range) | 9.0 (1.0–25.3) |

| ELTS | |

| Low-risk | 55 (62.5) |

| Intermediate-risk | 15 (17.0) |

| High-risk | 3 (3.4) |

| Unknown | 15 (7.0) |

| Ph+ ACAs | |

| Yes | 5 (5.7) |

| No | 75 (85.2) |

| Unknown | 8 (9.1) |

| Time Since TKI Initiation | Evaluable Patients, n | Molecular Response, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optimal | Warning | Failure | ||

| 3 m | 57 | 39 (68.4) | 12 (21.1) | 6 (10.5) |

| 6 m | 50 | 30 (60.0) | 16 (32.0) | 4 (8.0) |

| 12 m | 52 | 28 (53.8) | 14 (26.9) | 10 (19.2) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; An, W.; Liu, C.; Zhang, B.; Chen, Y.; Wan, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, L.; Liu, F.; Zhang, L.; et al. Early BCR::ABL1 Reduction as a Predictor of Deep Molecular Response in Pediatric Chronic-Phase Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Cancers 2025, 17, 3994. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243994

Wang X, An W, Liu C, Zhang B, Chen Y, Wan Y, Li X, Liu L, Liu F, Zhang L, et al. Early BCR::ABL1 Reduction as a Predictor of Deep Molecular Response in Pediatric Chronic-Phase Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Cancers. 2025; 17(24):3994. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243994

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xingchen, Wenbin An, Chenmeng Liu, Bang Zhang, Yunlong Chen, Yang Wan, Xiaolan Li, Lipeng Liu, Fang Liu, Li Zhang, and et al. 2025. "Early BCR::ABL1 Reduction as a Predictor of Deep Molecular Response in Pediatric Chronic-Phase Chronic Myeloid Leukemia" Cancers 17, no. 24: 3994. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243994

APA StyleWang, X., An, W., Liu, C., Zhang, B., Chen, Y., Wan, Y., Li, X., Liu, L., Liu, F., Zhang, L., Zou, Y., Chen, X., Chen, Y., Guo, Y., Hu, T., Zhang, Y., Zhu, X., & Yang, W. (2025). Early BCR::ABL1 Reduction as a Predictor of Deep Molecular Response in Pediatric Chronic-Phase Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Cancers, 17(24), 3994. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243994