Metabolomic Insights into Prostate Cancer Treatment and Relapse

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Participants

2.2. Metabolomics Analysis and Preprocessing

2.3. Statistical Analysis and Models

3. Results

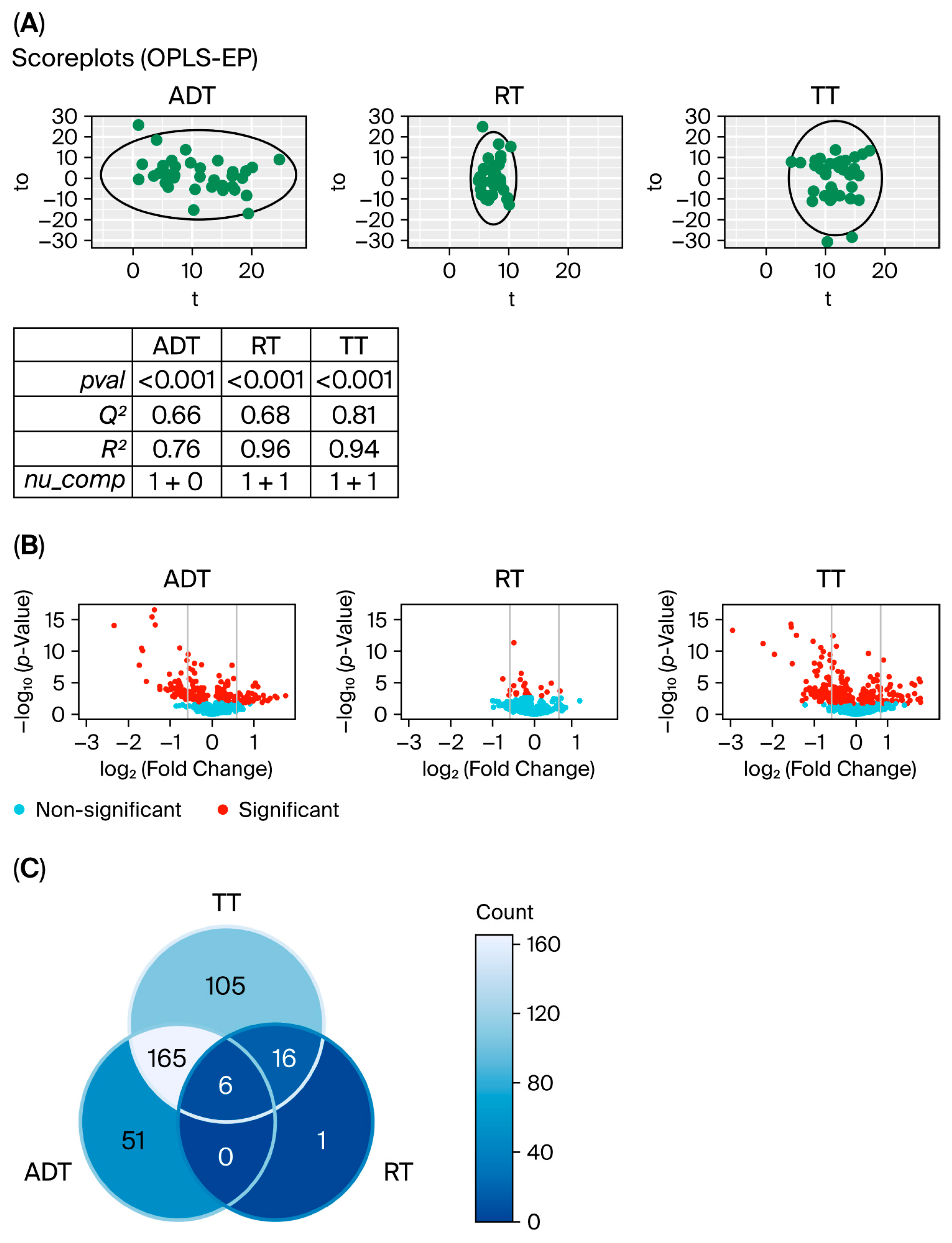

3.1. Changes in Metabolic Levels During Treatment of Prostate Cancer

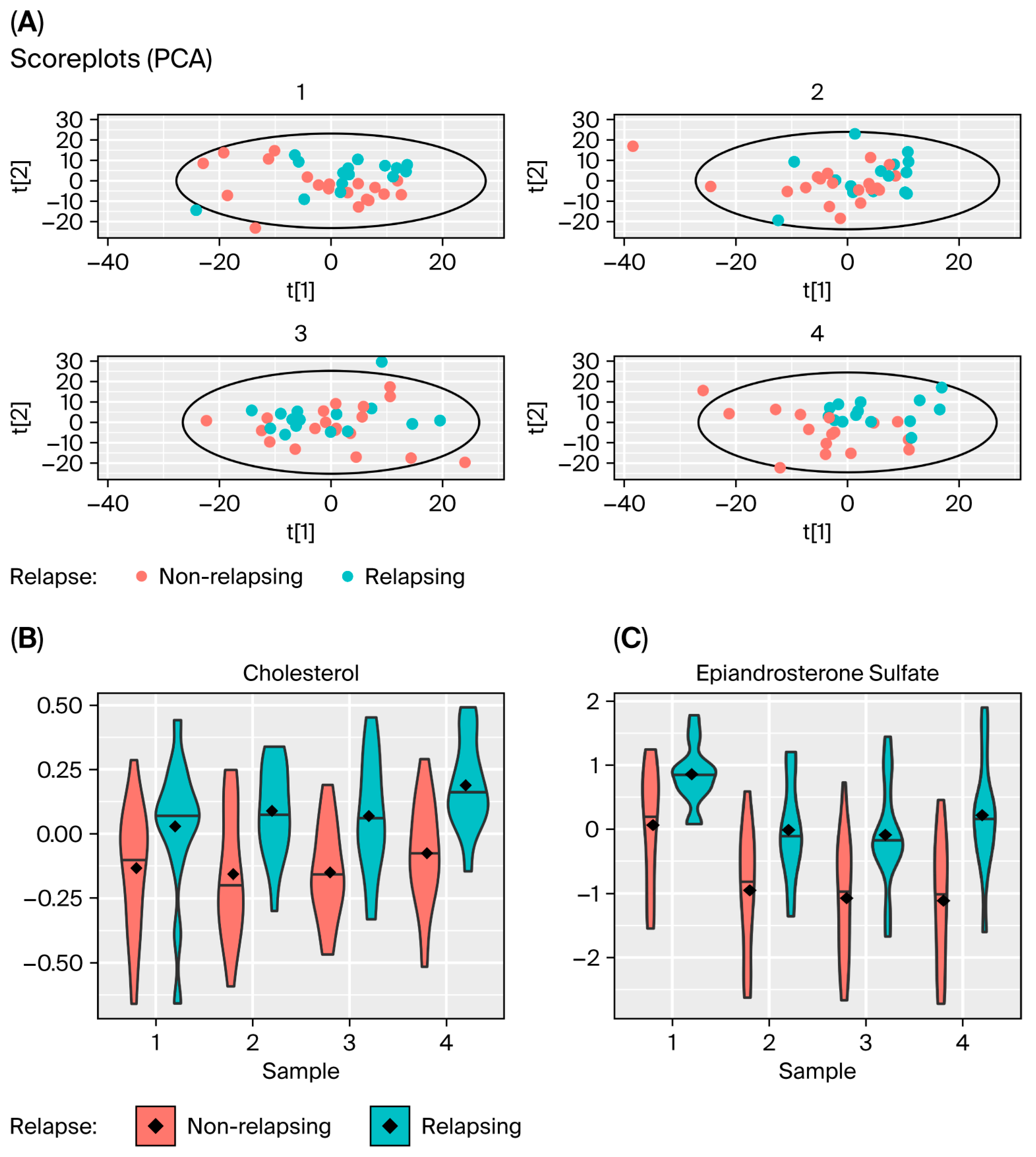

3.2. Comparing Changes in Metabolic Levels for Patients Who Relapse with Those That Do Not

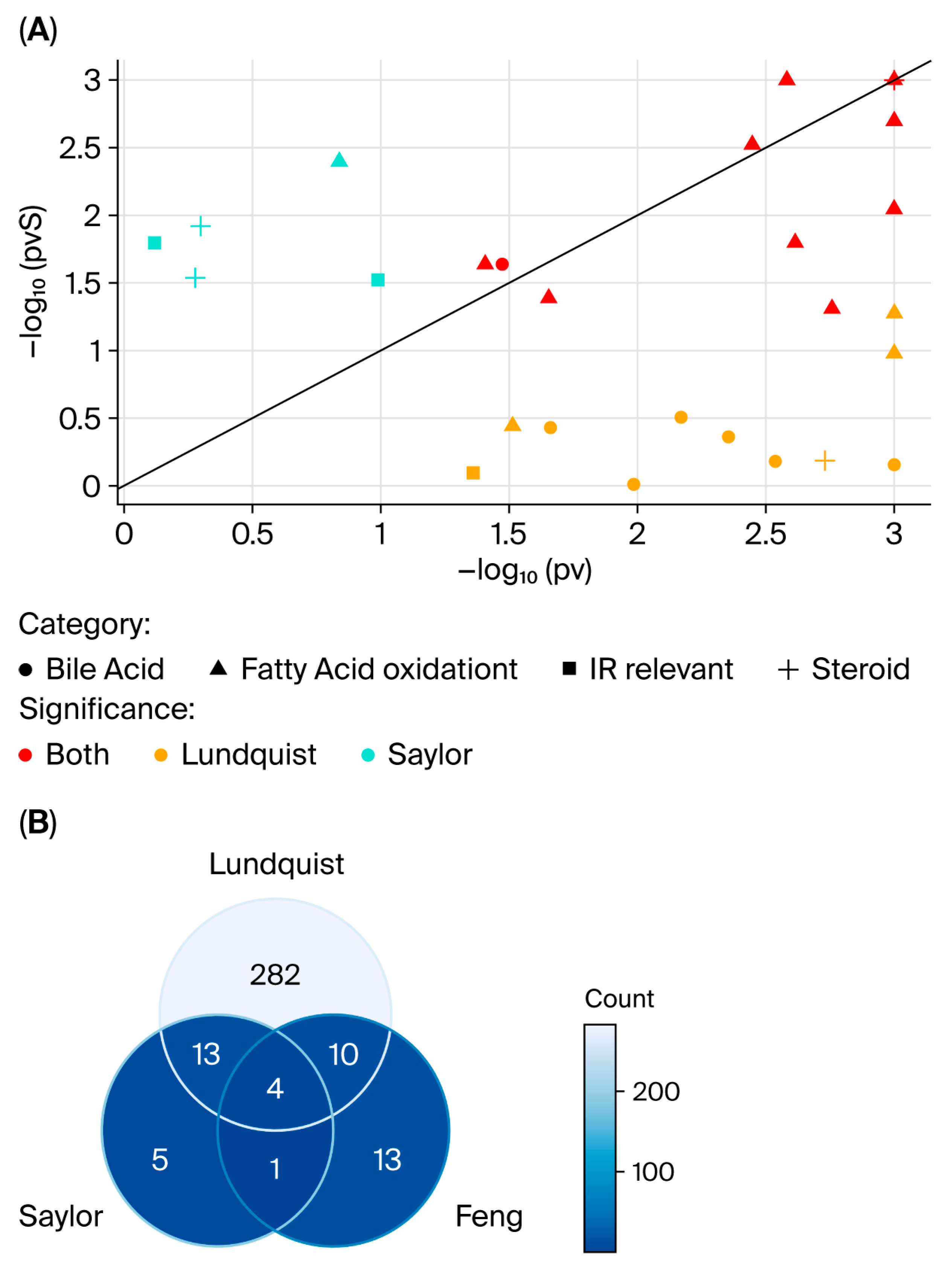

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADT | Androgen Deprivation Therapy |

| RT | Radiotherapy |

| UPLC-MS/MS | Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| PLS | Partial Least Squares |

| OPLS | Orthogonal Projections to Latent Structures |

| OPLS-EP | OPLS–Effect Projection |

| OPLS-DA | OPLS–Discriminant Analysis |

| CV-ANOVA | Cross-Validated ANOVA |

| FC | Fold Change |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

References

- Murthy, V.; Maitre, P.; Kannan, S.; Panigrahi, G.; Krishnatry, R.; Bakshi, G.; Prakash, G.; Pal, M.; Menon, P.; Phurailatpam, R.; et al. Prostate-Only Versus Whole-Pelvic Radiation Therapy in High-Risk and Very High-Risk Prostate Cancer (POP-RT): Outcomes from Phase III Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 1234–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attard, G.; Murphy, L.; Clarke, N.W.; Cross, W.; Jones, R.J.; Parker, C.C.; Gillessen, S.; Cook, A.; Brawley, C.; Amos, C.L.; et al. Abiraterone acetate and prednisolone with or without enzalutamide for high-risk non-metastatic prostate cancer: A meta-analysis of primary results from two randomised controlled phase 3 trials of the STAMPEDE platform protocol. Lancet 2022, 399, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteva, A.; Feng, J.; van der Wal, D.; Huang, S.C.; Simko, J.P.; DeVries, S.; Chen, E.; Schaeffer, E.M.; Morgan, T.M.; Sun, Y.; et al. Prostate cancer therapy personalization via multi-modal deep learning on randomized phase III clinical trials. npj Digit. Med. 2022, 5, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, R.S.; Vander Heiden, M.G.; Giovannucci, E.; Mucci, L.A. Metabolomic Biomarkers of Prostate Cancer: Prediction, Diagnosis, Progression, Prognosis, and Recurrence. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2016, 25, 887–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.M.; Mahon, K.L.; Weir, J.M.; Mundra, P.A.; Spielman, C.; Briscoe, K.; Gurney, H.; Mallesara, G.; Marx, G.; Stockler, M.R.; et al. A distinct plasma lipid signature associated with poor prognosis in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 141, 2112–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.M.; Huynh, K.; Kohli, M.; Tan, W.; Azad, A.A.; Yeung, N.; Mahon, K.L.; Mak, B.; Sutherland, P.D.; Shephard, A.; et al. Aberrations in circulating ceramide levels are associated with poor clinical outcomes across localised and metastatic prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2021, 24, 860–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beger, R.D. A review of applications of metabolomics in cancer. Metabolites 2013, 3, 552–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Covarrubias, V.; Martinez-Martinez, E.; Del Bosque-Plata, L. The potential of metabolomics in biomedical applications. Metabolites 2022, 12, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, J.L.; Shockcor, J.P. Metabolic profiles of cancer cells. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2004, 4, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spratlin, J.L.; Serkova, N.J.; Eckhardt, S.G. Clinical applications of metabolomics in oncology: A review. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, R.; Lundstedt, T.; Trygg, J. Chemometrics in metabolomics—A review in human disease diagnosis. Anal. Chim. Acta 2010, 659, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glimelius, B.; Melin, B.; Enblad, G.; Alafuzoff, I.; Beskow, A.; Ahlström, H.; Bill-Axelson, A.; Birgisson, H.; Björ, O.; Edqvist, P.H.; et al. U-CAN: A prospective longitudinal collection of biomaterials and clinical information from adult cancer patients in Sweden. Acta Oncol. 2018, 57, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åberg, A.M.; Bergström, S.H.; Thysell, E.; Tjon-Kon-Fat, L.-A.; Nilsson, J.A.; Widmark, A.; Thellenberg-Karlsson, C.; Bergh, A.; Wikström, P.; Lundholm, M. High Monocyte Count and Expression of S100A9 and S100A12 in Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells Are Associated with Poor Outcome in Patients with Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietzner, M.; Stewart, I.D.; Raffler, J.; Khaw, K.T.; Michelotti, G.A.; Kastenmüller, G.; Wareham, N.J.; Langenberg, C. Plasma metabolites to profile pathways in noncommunicable disease multimorbidity. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonsson, P.; Wuolikainen, A.; Thysell, E.; Chorell, E.; Stattin, P.; Wikström, P.; Antti, H. Constrained randomization and multivariate effect projections improve information extraction and biomarker pattern discovery in metabolomics studies involving dependent samples. Metabolomics 2015, 11, 1667–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wold, S.; Esbensen, K.; Geladi, P. Principal component analysis. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 1987, 2, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bylesjö, M.; Rantalainen, M.; Cloarec, O.; Nicholson, J.K.; Holmes, E.; Trygg, J. OPLS discriminant analysis: Combining the strengths of PLS-DA and SIMCA classification. J. Chemom. 2006, 20, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, L.; Trygg, J.; Wold, S. CV-ANOVA for significance testing of PLS and OPLS® models. J. Chemom. 2008, 22, 594–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple testing. J. R. Statist. Soc. B 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, J.T.; Lin, P.H.; Tolstikov, V.; Oyekunle, T.; Chen, E.Y.; Bussberg, V.; Greenwood, B.; Sarangarajan, R.; Narain, N.R.; Kiebish, M.A.; et al. Metabolomic effects of androgen deprivation therapy treatment for prostate cancer. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 3691–3702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.R.; Barb, J.J.; Allen, H.; Regan, J.; Saligan, L. Steroid Hormone Biosynthesis Metabolism Is Associated with Fatigue Related to Androgen Deprivation Therapy for Prostate Cancer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 642307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Liu, X.; Jiao, L.; Xu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Yang, C.; Zhang, W.; Sun, Y. Metabolomic evaluation of the response to endocrine therapy in patients with prostate cancer. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 729, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saylor, P.J.; Karoly, E.D.; Smith, M.R. Prospective study of changes in the metabolomic profiles of men during their first three months of androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 3677–3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolny-Rokicka, E.; Tukiendorf, A.; Wydmański, J.; Ostrowska, M.; Zembroń-Łacny, A. Lipid Status During Combined Treatment in Prostate Cancer Patients. Am. J. Mens Heal. 2019, 13, 1557988319876488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heemers, H.V.; Verhoeven, G.; Swinnen, J.V. Androgen activation of the sterol regulatory element-binding protein pathway: Current insights. Mol. Endocrinol. 2006, 20, 2265–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.M.; Kam, S.C. Metabolic effects of androgen deprivation therapy. Korean J. Urol. 2015, 56, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allott, E.H.; Howard, L.E.; Cooperberg, M.R.; Kane, C.J.; Aronson, W.J.; Terris, M.K.; Amling, C.L.; Freedland, S.J. Serum lipid profile and risk of prostate cancer recurrence: Results from the SEARCH database. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2014, 23, 2349–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thysell, E.; Surowiec, I.; Hörnberg, E.; Crnalic, S.; Widmark, A.; Johansson, A.I.; Stattin, P.; Bergh, A.; Moritz, T.; Antti, H.; et al. Metabolomic characterization of human prostate cancer bone metastases reveals increased levels of cholesterol. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e14175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raval, A.D.; Thakker, D.; Negi, H.; Vyas, A.; Kaur, H.; Salkini, M.W. Association between statins and clinical outcomes among men with prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2016, 19, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.S.; Schoenfeld, J.D.; Mailhot, R.B.; Shive, M.; Hartman, R.I.; Ogembo, R.; Mucci, L.A. Statins and prostate cancer recurrence following radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24, 1427–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, B.E.; Armstrong, A.J.; de Bono, J.; Sternberg, C.N.; Ryan, C.J.; Scher, H.I.; Smith, M.R.; Rathkopf, D.; Logothetis, C.J.; Chi, K.N.; et al. Effects of metformin and statins on outcomes in men with castration-resistant metastatic prostate cancer: Secondary analysis of COU-AA-301 and COU-AA-302. Eur. J. Cancer 2022, 170, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| All (n = 35) | Relapse (n = 15) | Metastasis (n = 12) | Deceased (n = 8) | Deceased, PCa (n = 4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age(years) | 58–79 | 58–79 | 58–79 | 61–75 | 61–75 |

| T-stage | |||||

| T1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| T2 | 13 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 2 |

| T3 | 17 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| T4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| N -stage | |||||

| N0 | 30 | 17 | 9 | 6 | 3 |

| N1 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| ISUP | |||||

| 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| 2 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| 3 | 8 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 17 | 10 | 9 | 4 | 3 |

| Time to event (years) 1 | 9.0 (1.6–9.5) | 3.3 (1.3–8.2) | 4.1 (2.4–6.1) | 6.3 (1.6–8.3) | 6.8 (6.2–8.3) |

| PSA at diagnosis/relapse 1 | 30.0 (6.7–232) | 2.9 (2.1–8.6) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lundquist, K.; Antti, H.; Thellenberg Karlsson, C. Metabolomic Insights into Prostate Cancer Treatment and Relapse. Cancers 2025, 17, 3993. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243993

Lundquist K, Antti H, Thellenberg Karlsson C. Metabolomic Insights into Prostate Cancer Treatment and Relapse. Cancers. 2025; 17(24):3993. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243993

Chicago/Turabian StyleLundquist, Kristina, Henrik Antti, and Camilla Thellenberg Karlsson. 2025. "Metabolomic Insights into Prostate Cancer Treatment and Relapse" Cancers 17, no. 24: 3993. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243993

APA StyleLundquist, K., Antti, H., & Thellenberg Karlsson, C. (2025). Metabolomic Insights into Prostate Cancer Treatment and Relapse. Cancers, 17(24), 3993. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243993