Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Lung Cancer: Advances in Imaging, Detection, and Prognosis

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background on Lung Cancer Epidemiology and Clinical Challenges

1.2. Motivation for AI/ML Applications in Lung Cancer

1.2.1. Throughput and Standardization

1.2.2. False-Positive (FP) Reduction and Risk Discrimination

1.2.3. Beyond Detection: Prognosis and Response

1.2.4. Data Integration and Real-World Fit

1.3. Scope and Objectives of the Review

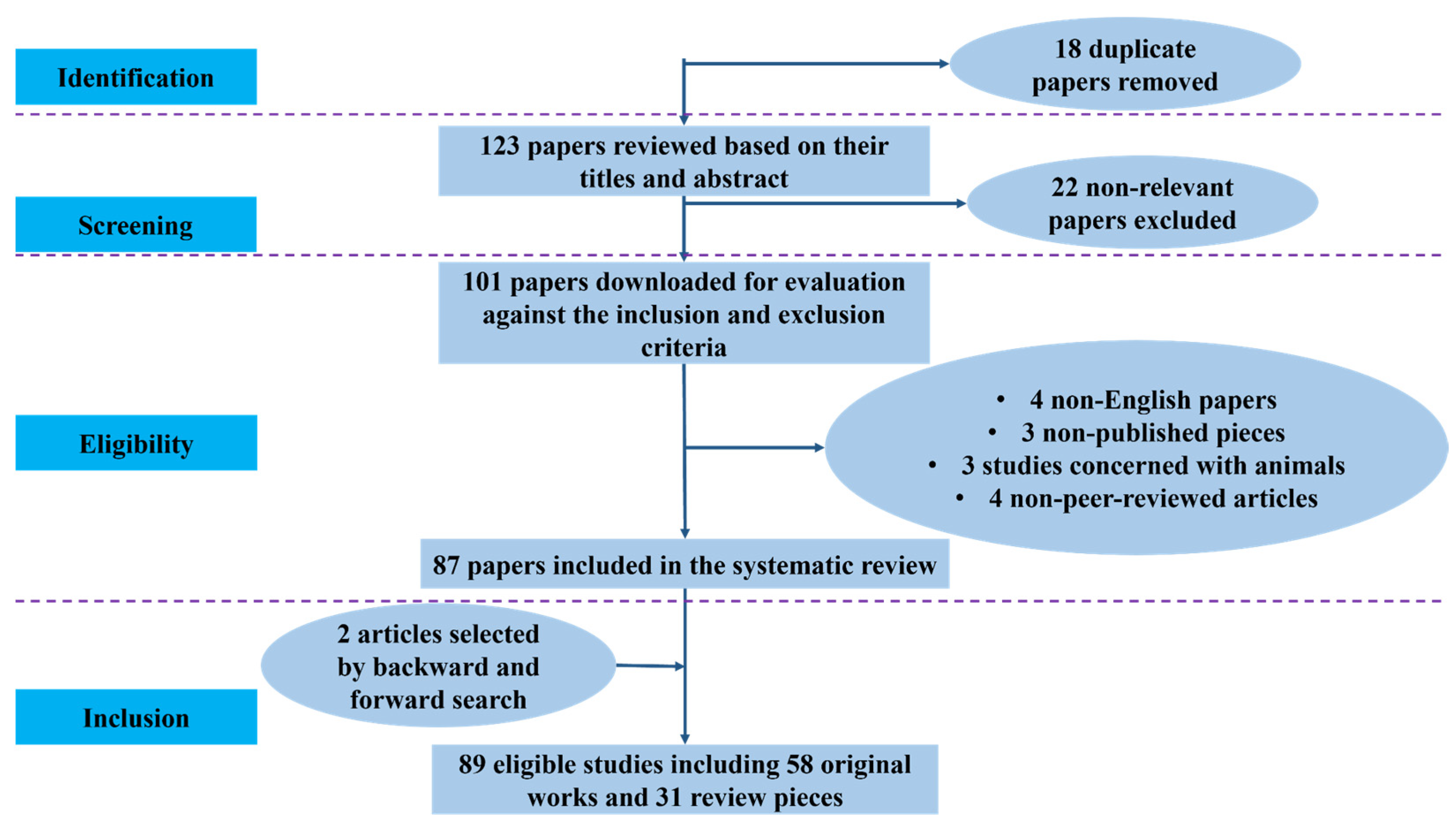

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

2.2. Summary of Literature Screening and Study Distribution

2.3. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

- Research using AI, ML, or DL methods for the diagnosis, categorization, staging, or prognosis of lung cancer.

- Research using AI-based techniques for image analysis, such as radiomics, feature extraction, segmentation, or combining imaging with molecular or clinical data.

- Original research papers that summarize AI/ML applications in lung cancer, including prospective, retrospective, cross-sectional, or model development investigations, as well as narrative or systematic reviews.

- English-language publications.

- Research that offers quantitative results (like diagnostic accuracy, predictive performance, or survival measures) and well-defined input data (like CT, PET, MRI, histology, or clinical data).

- Publications published from 2018 to 2025 in order to keep up with the latest trends and guarantee their applicability today.

- Research that does not use AI, ML, or DL algorithms for analysis or prediction.

- Studies were conducted on cancers other than lung cancer, such as colorectal, breast, or prostate cancer.

- Abstracts from conferences, letters, editorials, or commentary that do not provide enough quantitative data or methodological information.

- Publications that are not written in English.

- Studies that impede assessment or reproducibility due to inadequate model descriptions, unclear outcome measures, or inadequate data reporting.

- Redundant or overlapping research, unless it offers new information, larger datasets, or a significant shift in analytical viewpoints.

2.4. Approach for Organizing Themes

- AI in Lung Cancer Detection and Screening: this includes research on deep learning architectures for lung nodule recognition, picture segmentation, and false-positive reduction.

- AI in Risk Prediction and Prognosis, comprising studies that used survival analysis frameworks, multimodal data integration, and radiomics features to create or test predictive models.

- Malignancy grading, tumor classification, NSCLC staging, and comparison with traditional radiologists’ evaluations are all covered by AI in Lung Cancer Staging and Diagnosis.

3. AI in Lung Cancer Detection and Screening

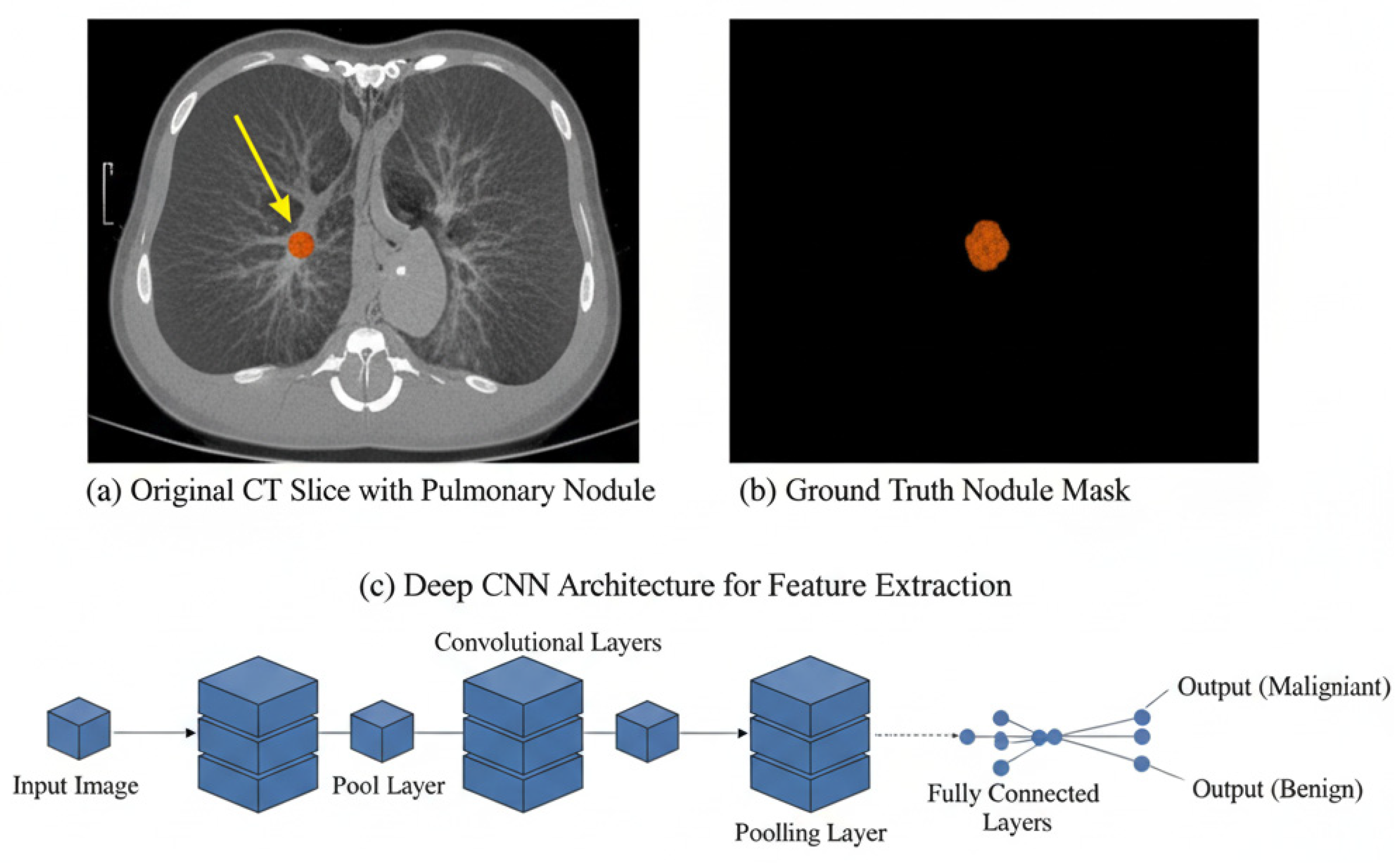

3.1. Pulmonary Nodule Detection

3.2. Segmentation Techniques Using DL Architectures

3.3. False Positive Reduction and Classification

| Reference | Algorithm | Source of Data | No. of Cases | Type of Validation | Main Finding | Quality Index Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cai et al. (2025) [5] | Mask R-CNN with ResNet50 architecture | Data from LUNA16 dataset | 888 patients from the LUNA16 dataset | 800 patients from an independent dataset from the Ali TianChi challenge | Using mask R-CNN and the ray-casting volume rendering algorithm can assist radiologists in diagnosing pulmonary nodules more accurately. | Mask R-CNN of weighted loss reaches sensitivities of 88.1% and 88.7% at 1 and 4 false positives per scan |

| Ren et al. (2020) [22] | MRC-DNN | Data from LIDC-IDRI dataset | 883 patients from the LIDC-IDRI dataset | 98 patients from the LIDC-IDRI dataset | MRC-DNN facilitates an accurate manifold learning approach for lung nodule classification based on 3D CT images | The classification accuracy on testing data is 0.90 with sensitivity of 0.81 and specificity of 0.95 |

| Cui et al. (2020) [21] | ResNet | Lung cancer screening data from three hospitals in China | 39,014 chest LDCT screening cases | Validation set (600 cases). External validation: the LUNA public database (888 studies) | The DL model was highly consistent with expert radiologists in terms of lung nodule identification | The AUC achieved 0.90 in the LUNA dataset |

| Yu et al. (2021) [24] | 3D Res U-Net | LIDC-IDRI | 1074 CT subcases from LIDC-IDRI | 174 CT data from 1074044 CT subcases | 3D Res U-Net can identify small nodules more effectively and improve its segmentation accuracy for large nodules | The accuracy of 3D ResNet50 is 87.3% and the AUC is 0.907 |

| Yuan et al. (2024) [26] | 3D ECA-ResNet | LUNA16/LIDC-IDRI | 1080 scans/888 scans | Comparison with state-of-the-art methods. | Multi-modal feature fusion of structured data and unstructured data is performed to classify nodules | Accuracy (94.89%), sensitivity (94.91%), and F1-score (94.65%) and lowest false positive rate (5.55%). |

| Liu et al. (2023) [27] | PiaNet | LIDC-IDRI | 302 CT scans from LIDC-IDRI | 52 CT scans from LIDC-IDRI | Pi-aNet is capable of more accurately detecting GGO nodules with diverse characteristics. | A sensitivity of 93.6% with only one false positive per scan |

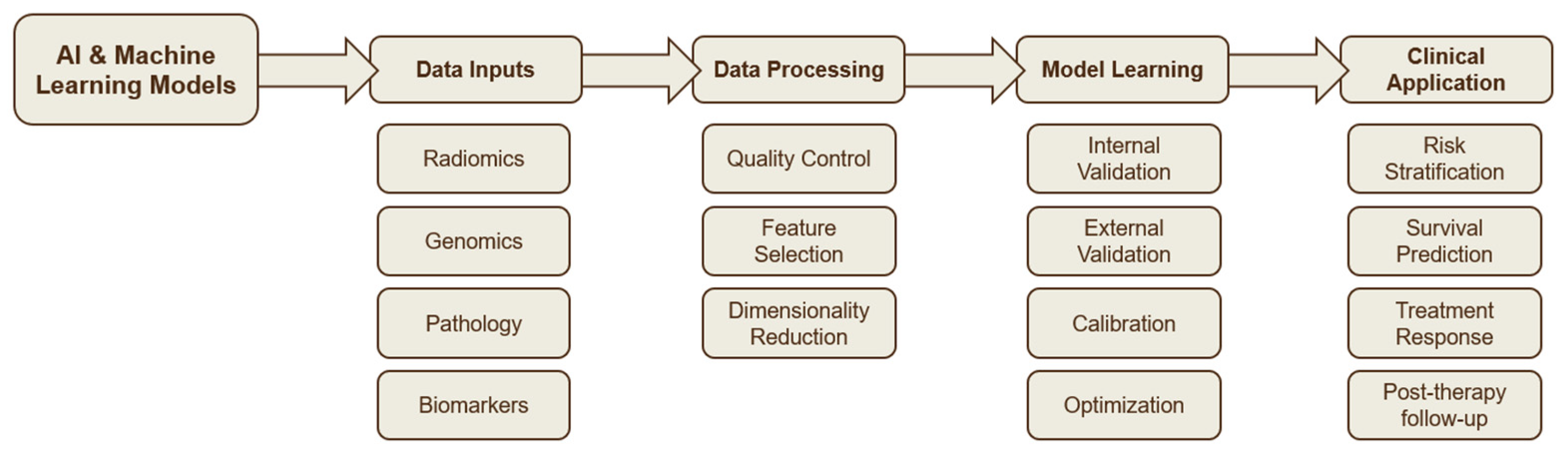

4. AI in Risk Prediction and Prognosis

4.1. Radiomics-Based Risk Models

4.2. Survival Prediction Models

4.3. Integration of AI with Clinical and Imaging Data

5. AI in Lung Cancer Staging and Diagnosis

5.1. Deep Learning Models for NSCLC Staging

5.2. Radiomics for Tumour Malignancy and Lymph-Node Assessment

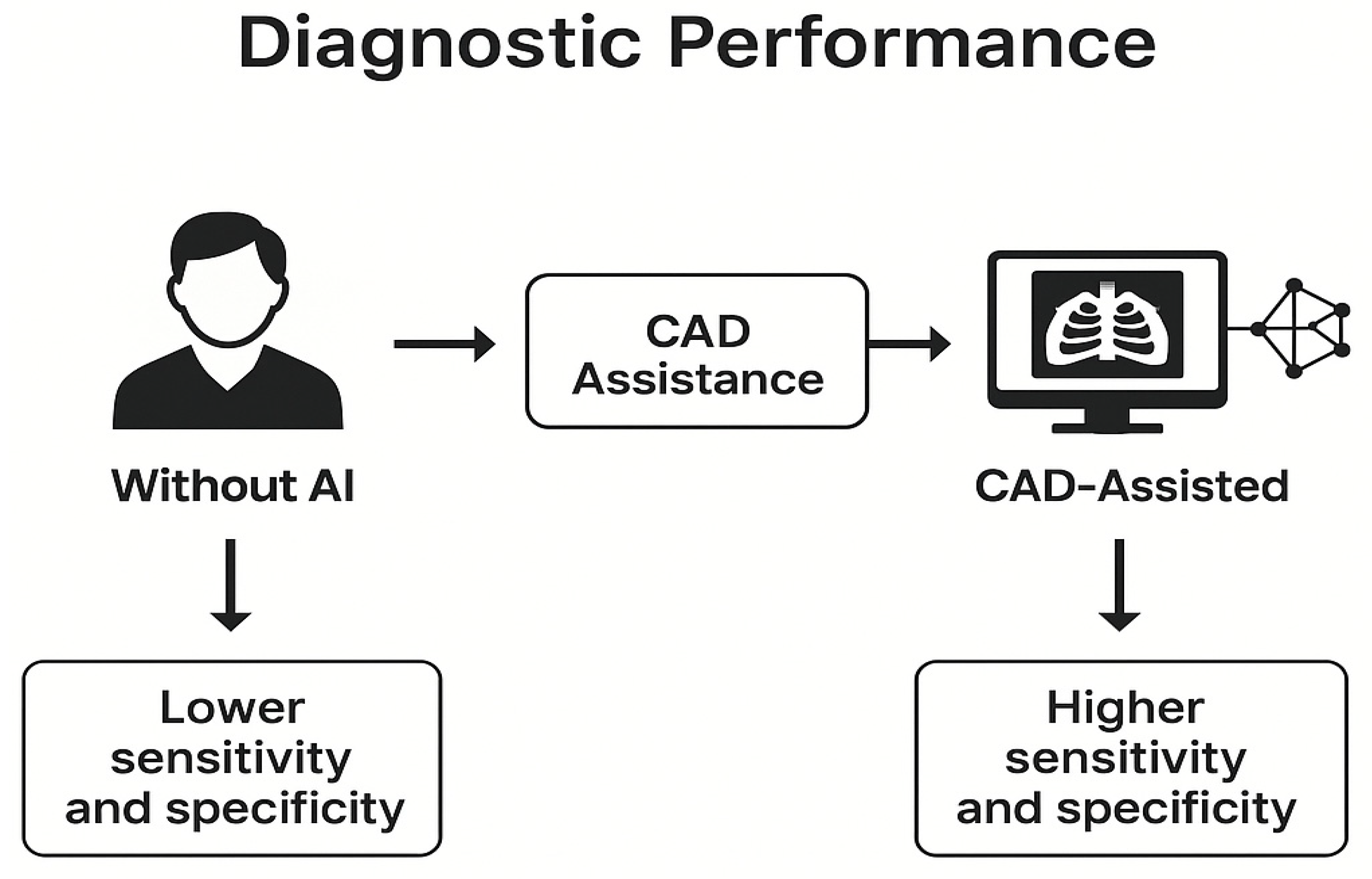

5.3. Comparison of AI Models with Traditional Radiologist Assessment

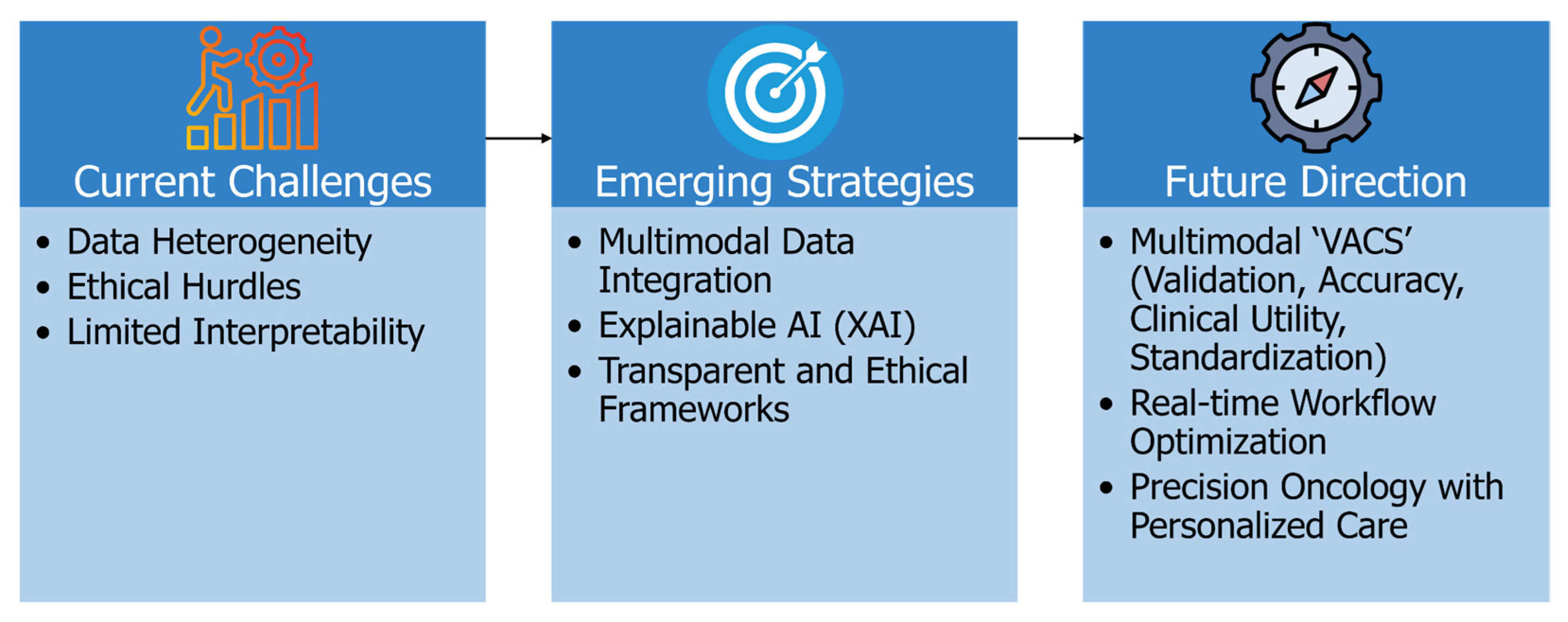

6. Challenges, Limitations, and Future Directions

6.1. Addressing Data Heterogeneity for Better Generalizability

6.2. Enhancing Model Interpretability and Clinical Trust

6.3. Navigating Ethical, Regulatory, and Reproducibility Challenges

6.4. Toward Intelligent, Personalized, and Real-Time Clinical Integration

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Callender, T.; Imrie, F.; Cebere, B.; Pashayan, N.; Navani, N.; van der Schaar, M.; Janes, S.M. Assessing eligibility for lung cancer screening using parsimonious ensemble machine learning models: A development and validation study. PLoS Med. 2023, 20, e1004287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cellina, M.; Cè, M.; Irmici, G.; Ascenti, V.; Khenkina, N.; Toto-Brocchi, M.; Martinenghi, C.; Papa, S.; Carrafiello, G. Artificial Intelligence in Lung Cancer Imaging: Unfolding the Future. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chassagnon, G.; De Margerie-Mellon, C.; Vakalopoulou, M.; Marini, R.; Hoang-Thi, T.-N.; Revel, M.-P.; Soyer, P. Artificial intelligence in lung cancer: Current applications and perspectives. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2023, 41, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çalışkan, M.; Tazaki, K. AI/ML advances in non-small cell lung cancer biomarker discovery. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1260374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, Y.; Wu, L.; Ergu, D.; Liao, Z.; Zhao, Y. Medical artificial intelligence for early detection of lung cancer: A survey. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 159, 111577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Causey, J.L.; Zhang, J.; Ma, S.; Jiang, B.; Qualls, J.A.; Politte, D.G.; Prior, F.; Zhang, S.; Huang, X. Highly accurate model for prediction of lung nodule malignancy with CT scans. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Wen, J.; Shen, X.; Shen, J.; Deng, J.; Zhao, M.; Xu, L.; Wu, C.; Yu, B.; Yang, M.; et al. Whole slide image based deep learning refines prognosis and therapeutic response evaluation in lung adenocarcinoma. npj Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Wang, F.; Cao, W.; Qin, C.; Dong, X.; Yang, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Luo, Z.; Zhao, L.; Yu, Y.; et al. Lung cancer risk prediction models based on pulmonary nodules: A systematic review. Thorac. Cancer 2022, 13, 664–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.; Li, Z.; Jiang, T.; Yang, C.; Li, N. Artificial intelligence in lung cancer: Current applications, future perspectives, and challenges. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1486310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozuka, T.; Matsukubo, Y.; Kadoba, T.; Oda, T.; Suzuki, A.; Hyodo, T.; Im, S.; Kaida, H.; Yagyu, Y.; Tsurusaki, M.; et al. Efficiency of a computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) system with deep learning in detection of pulmonary nodules on 1-mm-thick images of computed tomography. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2020, 38, 1052–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrix, W.; Hendrix, N.; Scholten, E.T.; Mourits, M.; Trap-de Jong, J.; Schalekamp, S.; Korst, M.; van Leuken, M.; van Ginneken, B.; Prokop, M.; et al. Deep learning for the detection of benign and malignant pulmonary nodules in non-screening chest CT scans. Commun. Med. 2023, 3, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcinkiewicz, A.M.; Buchwald, M.; Shanbhag, A.; Bednarski, B.P.; Killekar, A.; Miller, R.J.H.; Builoff, V.; Lemley, M.; Berman, D.S.; Dey, D.; et al. AI for Multistructure Incidental Findings and Mortality Prediction at Chest CT in Lung Cancer Screening. Radiology 2024, 312, e240541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, C.; Setio, A.A.A.; Scholten, E.T.; Gerke, P.K.; Bhattacharya, H.; Hoesein, F.A.M.; Brink, M.; Ranschaert, E.; de Jong, P.A.; Silva, M.; et al. Deep Learning for Lung Cancer Detection on Screening CT Scans: Results of a Large-Scale Public Competition and an Observer Study with 11 Radiologists. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 2021, 3, e210027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanan, M.; Alharbi, H.; Alotaibi, N.; Almasuood, L.; Aljoaid, S.; Alharbi, T.; Albraik, L.; Alothman, W.; Aljohani, H.; Alzahrani, A.; et al. AI-Driven Models for Diagnosing and Predicting Outcomes in Lung Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2024, 16, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avanzo, M.; Stancanello, J.; Pirrone, G.; Sartor, G. Radiomics and deep learning in lung cancer. Strahlenther. Onkol. Organ Dtsch. Rontgenges. Al 2020, 196, 879–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardila, D.; Kiraly, A.P.; Bharadwaj, S.; Choi, B.; Reicher, J.J.; Peng, L.; Tse, D.; Etemadi, M.; Ye, W.; Corrado, G.; et al. End-to-end lung cancer screening with three-dimensional deep learning on low-dose chest computed tomography. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 954–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, S.Ø.; Moore, D.A.; Surani, A.A.; Crosbie, P.A.J.; Rosenfeld, N.; Rintoul, R.C. Second Primary Lung Cancer—An Emerging Issue in Lung Cancer Survivors. J. Thorac. Oncol. Off. Publ. Int. Assoc. Study Lung Cancer 2024, 19, 1415–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, H.; Wang, S.; Song, J.; Gill, H.; Cheng, H. Update 2025: Management of Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Lung 2025, 203, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsinglawi, B.; Alshari, O.; Alorjani, M.; Mubin, O.; Alnajjar, F.; Novoa, M.; Darwish, O. An explainable machine learning framework for lung cancer hospital length of stay prediction. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiti, P.; Sharma, P.; Nand, M.; Bhatt, I.D.; Ramakrishnan, M.A.; Mathpal, S.; Joshi, T.; Pant, R.; Mahmud, S.; Simal-Gandara, J.; et al. Integrated Machine Learning and Chemoinformatics-Based Screening of Mycotic Compounds against Kinesin Spindle ProteinEg5 for Lung Cancer Therapy. Molecules 2022, 27, 1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, S.; Ming, S.; Lin, Y.; Chen, F.; Shen, Q.; Li, H.; Chen, G.; Gong, X.; Wang, H. Development and clinical application of deep learning model for lung nodules screening on CT images. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Y.; Tsai, M.-Y.; Chen, L.; Wang, J.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Jia, X.; Shen, C. A manifold learning regularization approach to enhance 3D CT image-based lung nodule classification. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2020, 15, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vachani, A.; Osarogiagbon, R.; Gotera Rive, C.; Seijo, L.; Bastarrika, G.; Ostrin, E.; Dennison, J.; Voyton, C.; Baudot, P.; Geremia, E.; et al. AI-assisted Lung Cancer Screening: Results From REALITY, A Pivotal Validation Study of an AI/ML-based Algorithm. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2025, 211, A5223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Cao, Y.; Yu, X.; Sun, J. Design of lung nodules segmentation and recognition algorithm based on deep learning. BMC Bioinform. 2021, 22, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqi, S.M.; Sharif, M.; Yasmin, M. Multistage segmentation model and SVM-ensemble for precise lung nodule detection. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2018, 13, 1083–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; An, L.; Zhu, Y.; Duan, C.; Kong, W.; Jiang, P.; Yu, Q.-Q. Machine Learning in Diagnosis and Prognosis of Lung Cancer by PET-CT. Cancer Manag. Res. 2024, 16, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wu, J.; Wang, N.; Zhang, X.; Bai, Y.; Guo, J.; Zhang, L.; Liu, S.; Tao, K. The value of artificial intelligence in the diagnosis of lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0273445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Cho, Y.; Shim, E.; Woo, H. Web-based infectious disease surveillance systems and public health perspectives: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Chen, A.; Liu, Z.; Wei, S.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; Shi, C. Machine learning driven prediction of drug efficacy in lung cancer: Based on protein biomarkers and clinical features. Life Sci. 2025, 375, 123706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, Y.; Sarangi, S.C.; Gupta, V.; Kumar, N.; Abraham, A. A Novel Context-Aware Feature Pyramid Networks With Kolmogorov-Arnold Modeling and XAI Framework for Robust Lung Cancer Detection. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 108992–109008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, F.; Asif Hasan, M.; Siddique, M.A.I.; Roy, T.; Kanti Shaha, T.; Islam, Y.; Paul, A.; Chowdhury, M.E.H. An End-to-End Concatenated CNN Attention Model for the Classification of Lung Cancer With XAI Techniques. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 96317–96336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Margerie-Mellon, C.; Chassagnon, G. Artificial intelligence: A critical review of applications for lung nodule and lung cancer. Diagn. Interv. Imaging 2023, 104, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Q.; Yang, L.; Lu, M.; Jin, R.; Ye, H.; Ma, T. The artificial intelligence and machine learning in lung cancer immunotherapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2023, 16, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, Z.; Gurram, P.; Amgai, B.; Lekkala, S.P.; Lokhandwala, A.; Manne, S.; Mohammed, A.; Koshiya, H.; Dewaswala, N.; Desai, R.; et al. Artificial Intelligence and Lung Cancer: Impact on Improving Patient Outcomes. Cancers 2023, 15, 5236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimpour, L.; Després, P.; Manem, V.S.K. Differential Radiomics-Based Signature Predicts Lung Cancer Risk Accounting for Imaging Parameters in NLST Cohort. Cancer Med. 2024, 13, e70359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arun, S.; Grosheva, M.; Kosenko, M.; Robertus, J.L.; Blyuss, O.; Gabe, R.; Munblit, D.; Offman, J. Systematic scoping review of external validation studies of AI pathology models for lung cancer diagnosis. npj Precis. Oncol. 2025, 9, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Arango Argoty, G.A.; Kagiampakis, I.; Khalid, M.H.; Jacob, E.; Bulusu, K.C.; Markuzon, N. Integrating knowledge graphs into machine learning models for survival prediction and biomarker discovery in patients with non–small-cell lung cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, X.; Hédou, J.; Bellan, G.; Thomas, P.-A.; Pages, P.-B.; D’Journo, X.-B.; Brouchet, L.; Rivera, C.; Falcoz, P.-E.; Gillibert, A.; et al. Predicthor: AI-Powered Predictive Risk Model for 30-Day Mortality and 30-Day Complications in Patients Undergoing Thoracic Surgery for Lung Cancer. Ann. Surg. Open Perspect. Surg. Hist. Educ. Clin. Approaches 2025, 6, e578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Germer, S.; Rudolph, C.; Labohm, L.; Katalinic, A.; Rath, N.; Rausch, K.; Holleczek, B.; AI-CARE Working Group; Handels, H. Survival analysis for lung cancer patients: A comparison of Cox regression and machine learning models. Int. J. Med. Inf. 2024, 191, 105607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duranti, L.; Tavecchio, L.; Rolli, L.; Solli, P. New Perspectives on Lung Cancer Screening and Artificial Intelligence. Life 2025, 15, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladbury, C.; Amini, A.; Govindarajan, A.; Mambetsariev, I.; Raz, D.J.; Massarelli, E.; Williams, T.; Rodin, A.; Salgia, R. Integration of artificial intelligence in lung cancer: Rise of the machine. Cell Rep. Med. 2023, 4, 100933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, V.H.; Minh, T.N.T.; Kha, Q.H.; Le, N.Q.K. Deep Learning Radiomics for Survival Prediction in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Patients from CT Images. J. Med. Syst. 2025, 49, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Q.; Luo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Xie, D.; Ye, T. Artificial intelligence in clinical applications for lung cancer: Diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2022, 60, 1974–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quanyang, W.; Yao, H.; Sicong, W.; Linlin, Q.; Zewei, Z.; Donghui, H.; Hongjia, L.; Shijun, Z. Artificial intelligence in lung cancer screening: Detection, classification, prediction, and prognosis. Cancer Med. 2024, 13, e7140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayad, S.; Al-Jamimi, H.A.; Kheir, A.E. Integrating Advanced Techniques: RFE-SVM Feature Engineering and Nelder-Mead Optimized XGBoost for Accurate Lung Cancer Prediction. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 29589–29600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragab, M.; Katib, I.; Sharaf, S.A.; Assiri, F.Y.; Hamed, D.; Al-Ghamdi, A.A.-M. Self-Upgraded Cat Mouse Optimizer With Machine Learning Driven Lung Cancer Classification on Computed Tomography Imaging. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 107972–107981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yu, H.; Gan, Y.; Wu, Z.; Li, E.; Li, X.; Cao, J.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, L.; Deng, H.; et al. Mining whole-lung information by artificial intelligence for predicting EGFR genotype and targeted therapy response in lung cancer: A multicohort study. Lancet Digit. Health 2022, 4, e309–e319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warkentin, M.T.; Al-Sawaihey, H.; Lam, S.; Liu, G.; Diergaarde, B.; Yuan, J.-M.; Wilson, D.O.; Atkar-Khattra, S.; Grant, B.; Brhane, Y.; et al. Radiomics analysis to predict pulmonary nodule malignancy using machine learning approaches. Thorax 2024, 79, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Sun, X.; Dang, K.; Li, K.; Guo, X.-W.; Chang, J.; Yu, Z.-Q.; Huang, F.-Y.; Wu, Y.-S.; Liang, Z.; et al. Toward an Expert Level of Lung Cancer Detection and Classification Using a Deep Convolutional Neural Network. Oncologist 2019, 24, 1159–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, C.; Saha, S.; Rahman, M.A.; Milu, M.M.H.; Higa, H.; Rashid, M.A.; Ahmed, N. Lung-AttNet: An Attention Mechanism-Based CNN Architecture for Lung Cancer Detection With Federated Learning. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 57369–57386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Hosny, A.; Zeleznik, R.; Parmar, C.; Coroller, T.; Franco, I.; Mak, R.H.; Aerts, H.J. Deep Learning Predicts Lung Cancer Treatment Response from Serial Medical Imaging. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 3266–3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Chen, J.; Chen, R.; Yang, Z.; Sheng, R.; Li, X.; Wang, T.; Liu, H.; Yang, F.; et al. Deep learning-based histomorphological subtyping and risk stratification of small cell lung cancer from hematoxylin and eosin-stained whole slide images. Genome Med. 2025, 17, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, E.; Muneer, A.; Zhang, J.; Xia, Y.; Li, X.; Zhou, C.; Heymach, J.V.; Wu, J.; Le, X. Progress and challenges of artificial intelligence in lung cancer clinical translation. npj Precis. Oncol. 2025, 9, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Shi, H.; Wang, H. Machine Learning and AI in Cancer Prognosis, Prediction, and Treatment Selection: A Critical Approach. J. MultidisciHealthc 2023, 16, 1779–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Wu, J.; Moustafa, N.; Bashir, A.K.; Yu, K. AI-Driven Synthetic Biology for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Drug Effectiveness-Cost Analysis in Intelligent Assisted Medical Systems. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2022, 26, 5055–5066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Hu, F.; Ma, X.; Yang, M.; Lin, S.; Su, A. Deep Neural Network-Assisted Terahertz Metasurface Sensors for the Detection of Lung Cancer Biomarkers. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 15698–15705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ren, J.; Tao, X.; Tang, W.; Zhao, S.; Zhou, L.; Huang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, N. Automatic segmentation of pulmonary lobes on low-dose computed tomography using deep learning. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, S.; Teo, P.T.; Abazeed, M.E. Deep learning for automated, motion-resolved tumor segmentation in radiotherapy. npj Precis. Oncol. 2025, 9, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; He, B.; Hu, Y.; Ren, M.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, J.; Ouyang, L.; Chu, H.; Gao, H.; et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Deep Learning and Radiomics in Lung Cancer Staging: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 938113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riahi, T.; Shateri-Amiri, B.; Najafabadi, A.H.; Garazhian, S.; Radkhah, H.; Zooravar, D.; Mansouri, S.; Aghazadeh, R.; Bordbar, M.; Raiszadeh, S. Lung Cancer Management: Revolutionizing Patient Outcomes Through Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence. Cancer Rep. 2025, 8, e70240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Guo, J.; Cui, X.; Veldhuis, R.N.J.; Oudkerk, M.; van Ooijen, P.M.A. Automatic Pulmonary Nodule Detection in CT Scans Using Convolutional Neural Networks Based on Maximum Intensity Projection. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2020, 39, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, Y.; Kudo, Y.; Maehara, S.; Amemiya, R.; Masuno, R.; Park, J.; Ikeda, N. Radiomics with Artificial Intelligence for the Prediction of Early Recurrence in Patients with Clinical Stage IA Lung Cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 29, 8185–8193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Prakash, N.; Jain, A. Particle Swarm Optimization-Based Random Forest Framework for the Classification of Chronic Diseases. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 133931–133946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinjanka, Y.; Kaur, V.; Musa, U.I.; Kaur, K. ML-based early detection of lung cancer: An integrated and in-depth analytical framework. Discov. Artif. Intell. 2024, 4, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obayya, M.; Arasi, M.A.; Alruwais, N.; Alsini, R.; Mohamed, A.; Yaseen, I. Biomedical Image Analysis for Colon and Lung Cancer Detection Using Tuna Swarm Algorithm With Deep Learning Model. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 94705–94712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, Y.; Jin, Z.; Wu, J.; Deng, J.; Zhang, L.; Su, H.; Jiang, G.; Liu, H.; Xie, D.; Cao, N.; et al. Development and Validation of a Deep Learning Model for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Survival. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e205842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, A. Early Detection of Lung Cancer Using Predictive Modeling Incorporating CTGAN Features and Tree-Based Learning. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 34321–34333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geppert, J.; Asgharzadeh, A.; Brown, A.; Stinton, C.; Helm, E.J.; Jayakody, S.; Todkill, D.; Gallacher, D.; Ghiasvand, H.; Patel, M.; et al. Software using artificial intelligence for nodule and cancer detection in CT lung cancer screening: Systematic review of test accuracy studies. Thorax 2024, 79, 1040–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Xiong, S.; Ren, Q.; Wang, J.; Li, M.; Yang, L.; Wu, D.; Tang, K.; Pan, X.; Chen, F.; et al. Deep learning using histological images for gene mutation prediction in lung cancer: A multicentre retrospective study. Lancet Oncol. 2025, 26, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, S.P.; Sisodia, P.S.; Mishra, R.; Singh, D.P. Performance of machine learning algorithms for lung cancer prediction: A comparative approach. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhael, P.G.; Wohlwend, J.; Yala, A.; Karstens, L.; Xiang, J.; Takigami, A.K.; Bourgouin, P.P.; Chan, P.; Mrah, S.; Amayri, W.; et al. Sybil: A Validated Deep Learning Model to Predict Future Lung Cancer Risk From a Single Low-Dose Chest Computed Tomography. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 2191–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, H.-Y.; Chao, H.-S.; Chen, Y.-M. Application of Artificial Intelligence in Lung Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coudray, N.; Ocampo, P.S.; Sakellaropoulos, T.; Narula, N.; Snuderl, M.; Fenyö, D.; Moreira, A.L.; Razavian, N.; Tsirigos, A. Classification and mutation prediction from non-small cell lung cancer histopathology images using deep learning. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1559–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishio, M.; Sugiyama, O.; Yakami, M.; Ueno, S.; Kubo, T.; Kuroda, T.; Togashi, K. Computer-aided diagnosis of lung nodule classification between benign nodule, primary lung cancer, and metastatic lung cancer at different image size using deep convolutional neural network with transfer learning. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Liu, X.; Tian, L.; Li, W.; He, P.; Huang, S.; He, F.; Pan, X. Artificial intelligence in precision medicine for lung cancer: A bibliometric analysis. Digit. Health 2025, 11, 20552076241300229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Tan, T.; Teng, X.; Sun, X.; Zhao, H.; Liu, L.; Xiao, Y.; Lee, B.; Li, Y.; et al. Deep Learning Methods for Lung Cancer Segmentation in Whole-Slide Histopathology Images-The ACDC@LungHP Challenge 2019. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2021, 25, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, J.; Song, Y.; Feng, D.; Fulham, M.; Cai, W. Knowledge-based Collaborative Deep Learning for Benign-Malignant Lung Nodule Classification on Chest CT. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2019, 38, 991–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.; Kim, K.H.; Singh, R.; Digumarthy, S.R.; Kalra, M.K. Validation of a Deep Learning Algorithm for the Detection of Malignant Pulmonary Nodules in Chest Radiographs. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2017135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wu, X.; Yang, P.; Jiang, G.; Luo, Y. Machine Learning for Lung Cancer Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prognosis. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2022, 20, 850–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacurari, A.C.; Bhattarai, S.; Muhammad, A.; Avram, C.; Mederle, A.O.; Rosca, O.; Bratosin, F.; Bogdan, I.; Fericean, R.M.; Biris, M.; et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Machine Learning AI Architectures in Detection and Classification of Lung Cancer: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, D.; Yamamoto, A.; Shimazaki, A.; Walston, S.L.; Matsumoto, T.; Izumi, N.; Tsukioka, T.; Komatsu, H.; Inoue, H.; Kabata, D.; et al. Artificial intelligence-supported lung cancer detection by multi-institutional readers with multi-vendor chest radiographs: A retrospective clinical validation study. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, I.; Furukawa, T.; Morise, M. The current issues and future perspective of artificial intelligence for developing new treatment strategy in non-small cell lung cancer: Harmonization of molecular cancer biology and artificial intelligence. Cancer Cell Int. 2021, 21, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavithran, M.S.; Saranyaraj, D. Lung cancer risk prediction using augmented machine learning pipelines with explainable AI. Front. Artif. Intell. 2025, 8, 1602775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Dou, Q.; Chen, H.; Qin, J.; Heng, P.-A. Multi-Task Deep Model With Margin Ranking Loss for Lung Nodule Analysis. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2020, 39, 718–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, H.; Gan, C.; Lin, H.; Dou, Q.; Tsougenis, E.; Huang, Q.; Cai, M.; Heng, P.-A. Weakly Supervised Deep Learning for Whole Slide Lung Cancer Image Analysis. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2020, 50, 3950–3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, A.; Pati, A.; Sahu, B.; Das, M.N.; Nayak, D.S.K.; Sahoo, G.; Kant, S. En-MinWhale: An Ensemble Approach Based on MRMR and Whale Optimization for Cancer Diagnosis. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 113526–113542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noaman, N.F.; Kanber, B.M.; Smadi, A.A.; Jiao, L.; Alsmadi, M.K. Advancing Oncology Diagnostics: AI-Enabled Early Detection of Lung Cancer Through Hybrid Histological Image Analysis. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 64396–64415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolarz, B.; Łukasiewicz, H.; Samulak, D.; Piekarska, E.; Kołaciński, R.; Romanowicz, H.; Cancer-Epidemiology, L. Pathogenesis, Treatment and Molecular Aspect (Review of Literature). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesiku, C.Y.; Garcia-Zapirain, B. AI-Enhanced Lung Cancer Prediction: A Hybrid Model’s Precision Triumph. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2025, 29, 6287–6300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Records Identified | Duplicates Removed | Screened (Title/Abstract) | Excluded | Full-Text Assessed | Included in Review | Detection & Screening | Risk Prediction & Prognosis | Staging & Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed | 55 | 11 | 44 | 4 | 40 | 33 | 12 | 10 | 11 |

| Scopus | 40 | 2 | 38 | 10 | 28 | 24 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| IEEE Xplore | 26 | 2 | 24 | 5 | 19 | 17 | 7 | 5 | 5 |

| Google Scholar | 20 | 3 | 17 | 3 | 14 | 13 | 6 | 5 | 2 |

| Total | 141 | 18 | 123 | 22 | 101 | 87 (+2 = 89) | 33 | 28 | 28 |

| Reference | Data Modality | Example Inputs | Common AI/ML Approaches | Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [15,32,35] | CT imaging (radiomics) | Nodule texture, shape, attenuation/density | CNNs (incl. 3D), ResNet/U-Net (segmentation), XGBoost | High spatial detail; non-invasive; widely available | Protocol heterogeneity (thickness, kernel); limited external validation |

| [32,34] | PET-CT | FDG uptake, SUV metrics, textural features | Hybrid CNN + radiomics, 3D ResNet | Combines metabolic and anatomic information | Higher cost; smaller datasets; standardization issues |

| [30,34,36] | Histopathology/WSI | H&E slide tiles, tissue micro-architecture | Multiple-instance learning, Transformers, Graph-attention networks | Cellular-scale insight; rich morphology | Annotation burden; domain shift; interpretability concerns |

| [33,37] | Genomics/Transcriptomics | Mutation profiles, gene-expression panels | Random forest, DeepSurv, graph-based embeddings | Captures biological mechanisms and pathways | Small sample sizes; batch effects; integration complexity |

| [19,38,39] | Clinical/EMR data | Age, stage, smoking, comorbidities, labs | Logistic/Cox models, gradient-boosted trees, stacking | Good calibration; practical to deploy | Missingness; coding variability; limited linkage to images |

| [15,37,40] | Multimodal integration | Combined imaging + clinical + omics | Early/late fusion, ensemble meta-learners | Strongest overall discrimination and calibration; translational relevance | Requires harmonized multi-site data; higher computing and governance needs |

| Reference | Approach | Typical Inputs | Example Modeling Choices | Reported Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [3,34,52] | Handcrafted radiomics for malignancy risk | CT or PET/CT radiomics ± basic clinical covariates | Feature selection (e.g., LASSO) + logistic/SVM/RF/XGBoost | Better discrimination than rules; gains with light clinical fusion |

| [2,41,42] | Deep radiomics/CNN features | End-to-end or CNN-derived features from CT ± clinical | CNNs, hybrid deep + classical learners | Complements hand-crafted features; improved accuracy with fusion |

| [1,72,73] | Survival from imaging features | Radiomics or deep features ± stage/histology/treatment | Cox/penalized Cox, RSF, DeepSurv | Stronger risk stratification than clinical-only; value of longitudinal scans |

| [4,37,44] | Multimodal clinical-imaging fusion | CT/PET with demographics, smoking, labs, pathology, or -omics | Early/late fusion; knowledge-guided graphs | Better calibration and transportability than single-source models |

| Reference | Domain | AI Focus | Role in NSCLC Staging | Strengths/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li et al. (2022) [79] | Radiomics | Deep Learning (CNNs) | CT/PET-based tumor & lymph-node segmentation for T/N staging | Standardizes imaging interpretation; needs large annotated datasets |

| Wang et al. (2019) [85] | Pathomics | Deep Learning | Tissue-level classification to distinguish invasive vs. non-invasive lesions | Improves histologic accuracy; limited pathology digitization |

| Wang et al. (2022) [47] | Genomics | Machine Learning | Integration of mutation and biomarker data with imaging for risk prediction | Enhances personalized staging; complex feature harmonization |

| Zhu et al. (2025) [53] | Immunomics | Deep Learning | Predicts immune response and metastatic potential | Aids stage-related prognosis; limited immune datasets |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arshad, M.F.; Chowdhury, A.T.; Sharif, Z.; Islam, M.S.B.; Sumon, M.S.I.; Mohammedkasim, A.; Chowdhury, M.E.H.; Pedersen, S. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Lung Cancer: Advances in Imaging, Detection, and Prognosis. Cancers 2025, 17, 3985. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243985

Arshad MF, Chowdhury AT, Sharif Z, Islam MSB, Sumon MSI, Mohammedkasim A, Chowdhury MEH, Pedersen S. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Lung Cancer: Advances in Imaging, Detection, and Prognosis. Cancers. 2025; 17(24):3985. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243985

Chicago/Turabian StyleArshad, Mohammad Farhan, Adiba Tabassum Chowdhury, Zain Sharif, Md. Sakib Bin Islam, Md. Shaheenur Islam Sumon, Amshiya Mohammedkasim, Muhammad E. H. Chowdhury, and Shona Pedersen. 2025. "Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Lung Cancer: Advances in Imaging, Detection, and Prognosis" Cancers 17, no. 24: 3985. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243985

APA StyleArshad, M. F., Chowdhury, A. T., Sharif, Z., Islam, M. S. B., Sumon, M. S. I., Mohammedkasim, A., Chowdhury, M. E. H., & Pedersen, S. (2025). Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Lung Cancer: Advances in Imaging, Detection, and Prognosis. Cancers, 17(24), 3985. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243985