Bone Health in Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer: Where We Stand and Where We Can Improve

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patients

2.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.1.3. Definition of Bone Prevention

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Objectives

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

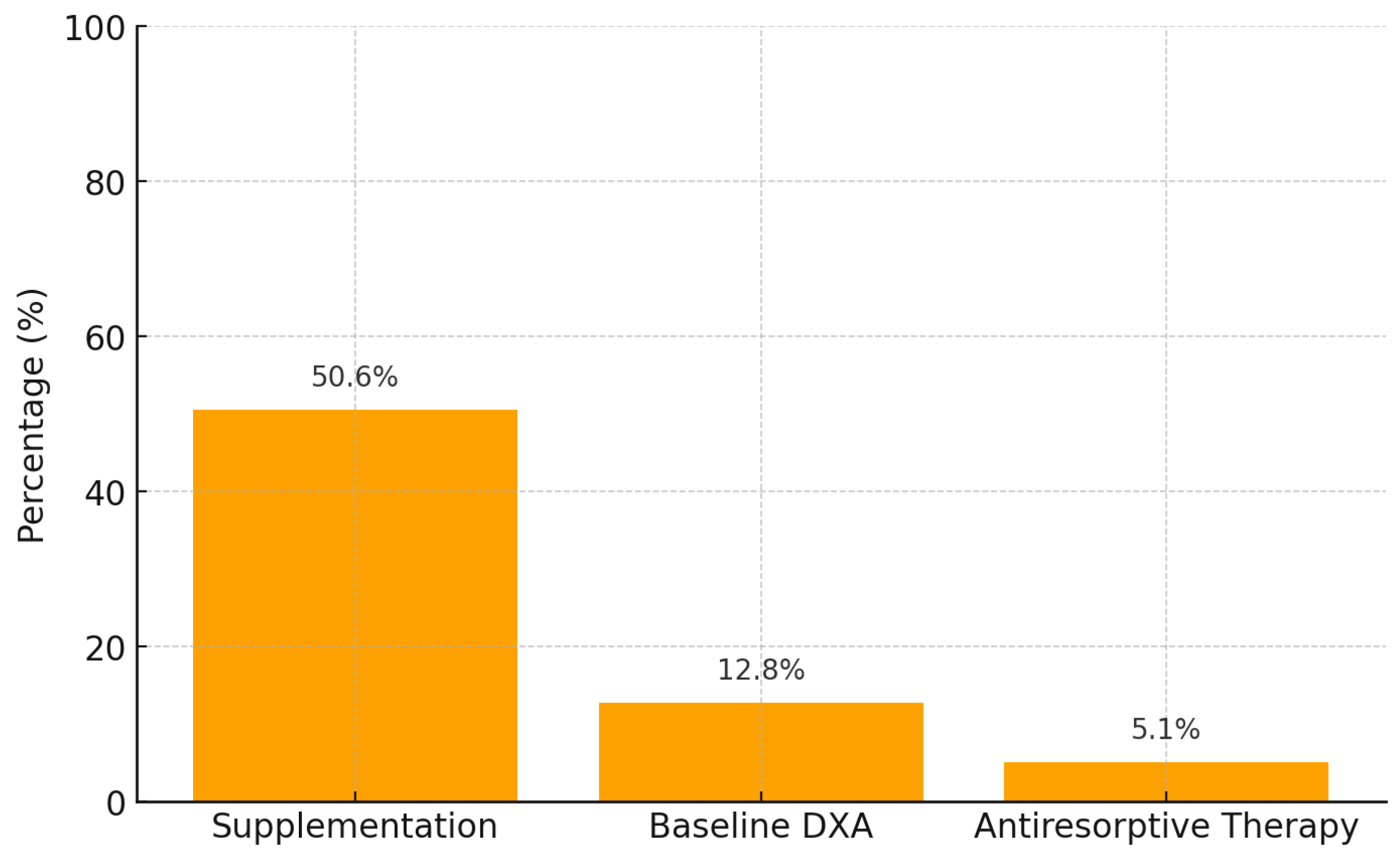

3.2. Bone Health Preventive Measures

3.3. Comparison with International Guidelines

3.4. Stratified Analyses

3.5. Exploratory Logistic Regression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cornford, P.; van den Bergh, R.C.N.; Briers, E.; Van den Broeck, T.; Brunckhorst, O.; Darraugh, J.; Eberli, D.; De Meerleer, G.; De Santis, M.; Farolfi, A.; et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-ISUP-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer-2024 Update. Part I: Screening, Diagnosis, and Local Treatment with Curative Intent. Eur. Urol. 2024, 86, 148–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gravis, G.; Boher, J.-M.; Joly, F.; Soulié, M.; Albiges, L.; Priou, F.; Latorzeff, I.; Delva, R.; Krakowski, I.; Laguerre, B.; et al. Androgen Deprivation Therapy (ADT) Plus Docetaxel Versus ADT Alone in Metastatic Non castrate Prostate Cancer: Impact of Metastatic Burden and Long-term Survival Analysis of the Randomized Phase 3 GETUG-AFU15 Trial. Eur. Urol. 2016, 70, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, K.N.; Chowdhury, S.; Bjartell, A.; Chung, B.H.; Gomes, A.J.P.d.S.; Given, R.; Juárez, A.; Merseburger, A.S.; Özgüroğlu, M.; Uemura, H.; et al. Apalutamide in PatientsWith Metastatic Castration-Sensitive Prostate Cancer: Final Survival Analysis of the Randomized, Double-Blind, Phase III TITAN Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 2294–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, K.N.; Agarwal, N.; Bjartell, A.; Chung, B.H.; Gomes, A.J.P.D.S.; Given, R.; Soto, A.J.; Merseburger, A.S.; Özgüroglu, M.; Uemura, H.; et al. Apalutamide for Metastatic, Castration-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fizazi, K.; Tran, N.; Fein, L.; Matsubara, N.; Rodriguez-Antolin, A.; Alekseev, B.Y.; Özgüroğlu, M.; Ye, D.; Feyerabend, S.; Protheroe, A.; et al. Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone in patients with newly diagnosed high-risk metastatic castrationsensitive prostate cancer (LATITUDE): Final overall survival analysis of a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 686–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fizazi, K.; Foulon, S.; Carles, J.; Roubaud, G.; McDermott, R.; Fléchon, A.; Tombal, B.; Supiot, S.; Berthold, D.; Ronchin, P.; et al. Abiraterone plus prednisone added to androgen deprivation therapy and docetaxel in de novo metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (PEACE-1): A multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 study with a 2 × 2 factorial design. Lancet 2022, 399, 1695–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagrodia, A.; Diblasio, C.J.; Wake, R.W.; Derweesh, I.H. Adverse effects of androgen deprivation therapy in prostate cancer: Current management issues. Indian J. Urol. 2009, 25, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiBlasio, C.J.; Malcolm, J.B.; Derweesh, I.H.; Womack, J.H.; Kincade, M.C.; Mancini, J.G.; Ogles, M.L.; Lamar, K.D.; Patterson, A.L.; Wake, R.W. Patterns of sexual and erectile dysfunction and response to treatment in patients receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2008, 102, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saylor, P.J.; Smith, M.R. Adverse effects of androgen deprivation therapy: Defining the problem and promoting health among men with prostate cancer. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 2010, 8, 211–223, Erratum in J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 2010, 8, xlv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraj, K.S.; Oerline, M.; Kaufman, S.R.; Dall, C.; Srivastava, A.; Caram, M.E.V.; Shahinian, V.B.; Hollenbeck, B.K. Adverse events in men with advanced prostate cancer treated with androgen biosynthesis inhibitors and androgen receptor inhibitors. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2024, 116, 1817–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahinian, V.B.; Kuo, Y.F.; Freeman, J.L.; Goodwin, J.S. Risk of the “androgen deprivation syndrome” in men receiving androgen deprivation for prostate cancer. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Tully, K.H.; Nguyen, D.D.; Herzog, P.; Jin, G.; Noldus, J.; Nguyen, P.L.; Kibel, A.S.; Sun, M.; McGregor, B.; Basaria, S.; et al. Risk of dementia and depression in young and middle-aged men presenting with nonmetastatic prostate cancer treated with androgen deprivation therapy. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2021, 4, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Washington. RUCA Approximate Codes. University of Washington Department of Health Services. Available online: https://depts.washington.edu/uwruca/ruca-approx.php (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Diez Roux, A.V.; Merkin, S.S.; Arnett, D.; Chambless, L.; Massing, M.; Nieto, F.J.; Sorlie, P.; Szklo, M.; Tyroler, H.A.; Watson, R.L. Neighborhood of residence and incidence of coronary heart disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Association of Urology. EAU Guidelines on Prostate Cancer; EAU Guidelines Office: Arnhem, The Netherlands, 2024; Available online: https://uroweb.org/guidelines/prostate-cancer (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Prostate Cancer. Version 2024. In Proceedings of the NCCN Plymouth Meeting, Plymouth, PA, USA, 5–7 April 2024; Available online: https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=1&id=1460 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Saylor, P.J.; Rumble, R.B.; Tagawa, S.T.; Eastham, J.; Finelli, A.; Reddy, C.A.; Kungel, T.M.; Nissenberg, M.G.; Michalski, J.M. Bone health and bone-targeted therapies for prostate cancer: ASCO clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 1736–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.R.; Egerdie, B.; Hernández Toriz, N.; Feldman, R.; Tammela, T.L.; Saad, F.; Heracek, J.; Szwedowski, M.; Ke, C. Denosumab in men receiving androgen-deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kanis, J.A.; Harvey, N.C.; Johansson, H.; Oden, A.; McCloskey, E.V.; Leslie, W.D. FRAX and fracture prediction without bone mineral density. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2020, 35, 2201–2208. [Google Scholar]

- Yee, E.F.T.; White, R.E.; Murata, G.H.; Handanos, C.; Hoffman, R.M. Osteoporosis Management in Prostate Cancer Patients Treated with Androgen Deprivation Therapy. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2007, 22, 1305–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Solomon, D.H.; Finkelstein, J.S.; Katz, J.N.; Mogun, H.; Avorn, J. Underuse of osteoporosis medications in elderly patients with fractures. Am. J. Med. 2003, 115, 398–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handforth, C.; Paggiosi, M.A.; Jacques, R.; Gossiel, F.; Eastell, R.; Walsh, J.S.; Brown, J.E. The impact of androgen deprivation therapy on bone microarchitecture in men with prostate cancer: A longitudinal observational study (The ANTELOPE Study). J. Bone Oncol. 2024, 47, 100611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Tripathi, A.; Pieczonka, C.; Cope, D.; McNatty, A.; Logothetis, C.; Guise, T. Bone health effects of androgen-deprivation therapy and androgen receptor inhibitors in patients with nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2021, 24, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.E.; Handforth, C.; Compston, J.E.; Cross, W.; Parr, N.; Selby, P.; Wood, S.; Drudge-Coates, L.; Walsh, J.S.; Mitchell, C.; et al. Guidance for the assessment and management of prostate cancer treatment-induced bone loss. A consensus position statement from an expert group. J. Bone Oncol. 2020, 25, 100311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polho, G.B.; Melo, A.A.R.; Filho, L.C.O.; Amaral, P.S.; Neto, F.L.; Soares, G.F.; Franco, A.S.; Bastos, D.A. Impact of Bisphosphonates in Hormone-sensitive Metastatic Prostate Cancer A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2025, 23, 102438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, A.; Nguyen, D.D.; Lalani, A.K.; Satkunasivam, R.; Aminoltejari, K.; Hird, A.; Roy, S.; Morgan, S.C.; Malone, S.; Kokorovic, A.; et al. Metabolic, cardiac, and bone health testing in patients with prostate cancer on androgen-deprivation therapy: A population-based assessment of adherence to therapeutic monitoring guidelines. Cancer 2025, 131, e35606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Oefelein, M.G.; Ricchiuti, V.; Conrad, W.; Resnick, M.I. Skeletal fractures negatively correlate with overall survival in men with prostate cancer. J. Urol. 2002, 168, 1005–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sing, C.; Lin, T.; Bartholomew, S.; Bell, J.S.; Bennett, C.; Beyene, K.; Bosco-Levy, P.; Bradbury, B.D.; Chan, A.H.Y.; Chandran, M.; et al. Global Epidemiology of Hip Fractures: Secular Trends in Incidence Rate, Post-Fracture Treatment, and All-Cause Mortality. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2023, 38, 1064–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llopis-Cardona, F.; Armero, C.; Hurtado, I.; García-Sempere, A.; Peiró, S.; Rodríguez-Bernal, C.L.; Sanfélix-Gimeno, G. Incidence of Subsequent Hip Fracture and Mortality in Elderly Patients: A Multistate Population-Based Cohort Study in Eastern Spain. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2022, 37, 1200–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jürisson, M.; Raag, M.; Kallikorm, R.; Lember, M.; Uusküla, A. The Impact of Hip Fracture on Mortality in Estonia: A Retrospective Population-Based Cohort Study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2017, 18, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Shuang, H.; Qingjian, W.; Jingzhen, Z.; Ji, Z.; Yu, C. Bone health management in endocrine-treated patients with prostate cancer: A summary of evidence. BMC Urol. 2024, 24, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Encarnación, J.A.; Morillo Macías, V.; De la Fuente Muñoz, I.; Soria, V.D.; Fernández Fornos, L.; Antequera, M.A.; Rey, O.A.; García Martínez, V.; Alonso-Romero, J.L.; García Gómez, R. Apalutamide and Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy in Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer: Multicenter Real-World Study. Cancers 2025, 17, 2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boegemann, M.; Bennamoun, M.; Dourthe, L.M.; Encarnacion, J.A.; Hegele, A.; Hellmis, E.; Latorzeff, I.; Leicht, W.; Oñate-Celdrán, J.; Rosino-Sánchez, A.; et al. Final analysis of ArtemisR, a European real-world retrospective study of apalutamide for the treatment of patients with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Abad, A.; Backhaus, M.R.; Gómez, G.S.; Avellaneda, E.C.; Alarcón, C.M.; Cubillana, P.L.; Giménez, P.Y.; Rodríguez, P.d.P.; Fita, M.J.J.; Durán, M.C.; et al. Real-world prostate-specific antigen reduction and survival outcomes of metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer patients treated with apalutamide: An observational, retrospective, and multicentre study. Prostate Int. 2023, 12, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Encarnación Navarro, J.A.; Morillo Macías, V.; Borrás Calbo, M.; De la Fuente Muñoz, I.; Lozano Martínez, A.; García Martínez, V.; Fernández Fornos, L.; Guijarro Roche, M.; Amr Rey, O.; García Gómez, R. Multicenter Real-World Study: 432 Patients with Apalutamide in Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Preventive/Therapeutic Measure | Clinical Practice | Guideline Recommendation (EAU, NCCN, ASCO, NOGG) |

|---|---|---|

| Calcium + Vitamin D supplementation | 79 (50.6%) | 100% of patients on ADT should receive supplementation, regardless of baseline bone mineral density (BMD). |

| Baseline and follow-up DEXA scan | 20 (12.8%) | Baseline DEXA scan mandatory before initiating ADT; repeat every 1–2 years. |

| Antiresorptive therapy (Denosumab/Prolia®) in osteoporosis | 8 (5.1%) | Indicated in all patients with osteoporosis (T-score ≤ −2.5). |

| Documented fragility fractures | N = 2 | High incidence expected without prevention; active prevention strongly recommended. |

| Mean age | 74.2 ± 8.2 years | Advanced age is a major risk factor requiring systematic preventive measures. |

| Mean ADT duration | 37.3 ± 19.2 months | Risk of bone loss increases after 6–12 months of ADT and accumulates with treatment duration. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Encarnación, J.A.; López-Jiménez, E.; Alonso-Romero, J.L.; Ruiz, P.; Ros, S.; De la Fuente, M.I.; López, F.; Cárdenas, E.; Laborda, A.; Sánchez-Pérez, M.; et al. Bone Health in Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer: Where We Stand and Where We Can Improve. Cancers 2025, 17, 3977. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243977

Encarnación JA, López-Jiménez E, Alonso-Romero JL, Ruiz P, Ros S, De la Fuente MI, López F, Cárdenas E, Laborda A, Sánchez-Pérez M, et al. Bone Health in Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer: Where We Stand and Where We Can Improve. Cancers. 2025; 17(24):3977. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243977

Chicago/Turabian StyleEncarnación, Juan Antonio, Enrique López-Jiménez, Jose Luis Alonso-Romero, Paula Ruiz, Silverio Ros, Maria Isabel De la Fuente, Francisco López, Enrique Cárdenas, Ana Laborda, Marta Sánchez-Pérez, and et al. 2025. "Bone Health in Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer: Where We Stand and Where We Can Improve" Cancers 17, no. 24: 3977. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243977

APA StyleEncarnación, J. A., López-Jiménez, E., Alonso-Romero, J. L., Ruiz, P., Ros, S., De la Fuente, M. I., López, F., Cárdenas, E., Laborda, A., Sánchez-Pérez, M., Rodríguez, C., Manso, C., Ortega-López, N. D., López-Cubillana, P., Guzman Martínez-Valls, P. L., Cao-Avellaneda, E., López-González, P. Á., & López-Abad, A. (2025). Bone Health in Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer: Where We Stand and Where We Can Improve. Cancers, 17(24), 3977. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243977