Gemcitabine + Cisplatin + S-1 Treatment for Advanced Cholangiocarcinoma: Cost-Effective, with Better Progression-Free Survival Versus Standard Treatment with Gemcitabine + Cisplatin + Durvalumab

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

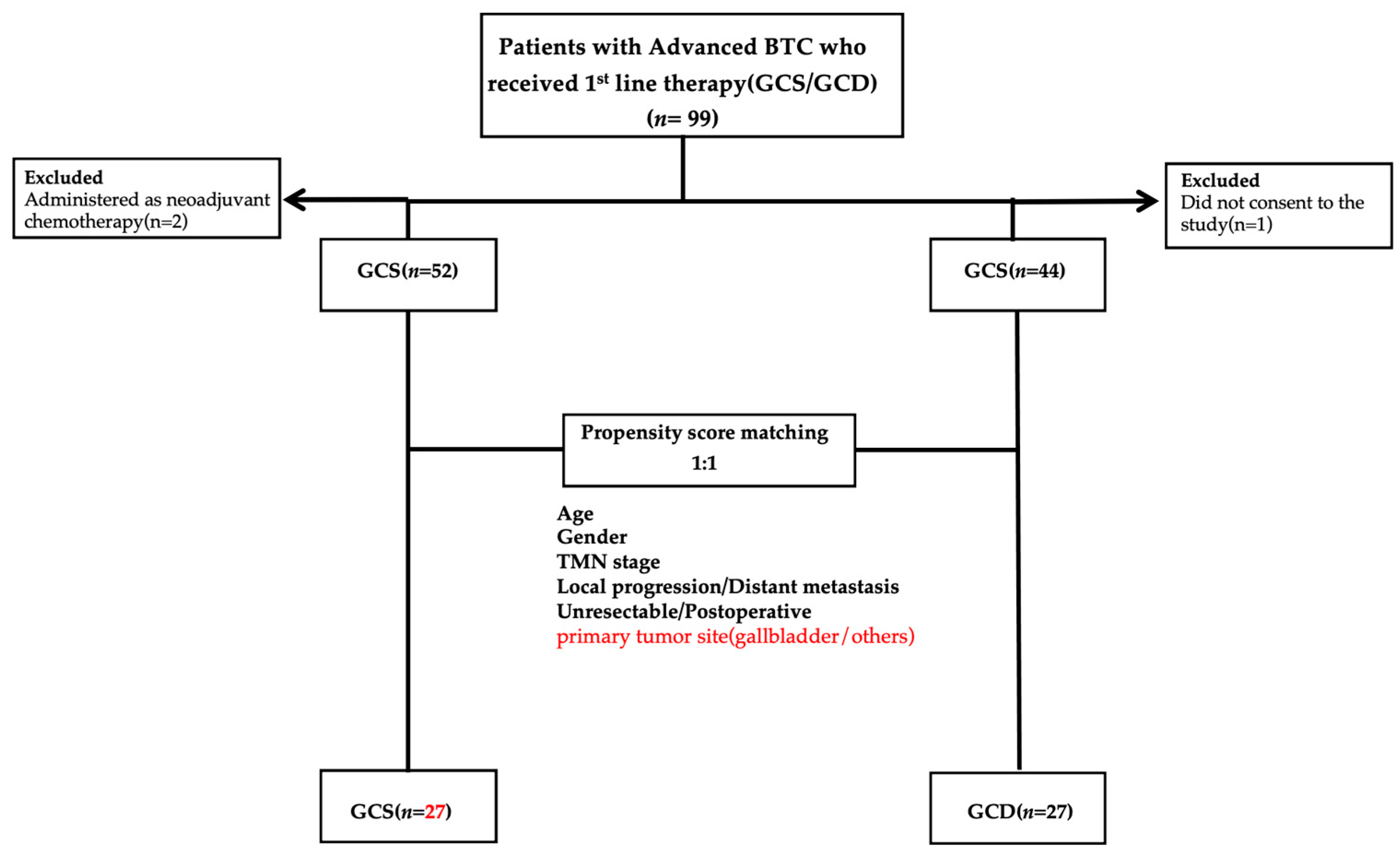

2.1. Patients

2.2. Evaluation of Therapeutic Response and Safety

2.3. Treatment Protocol

2.4. Measured Parameters

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

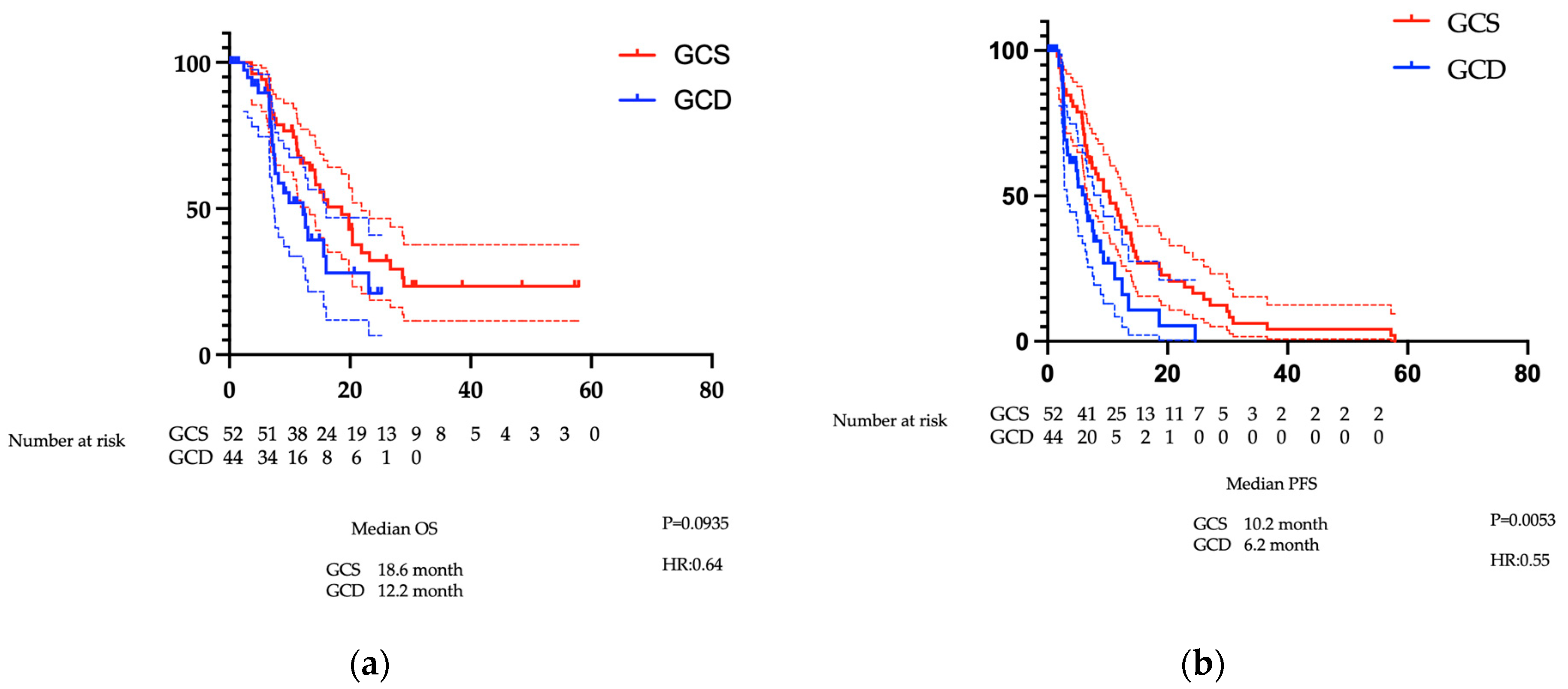

3.1. Results Before PSM

3.1.1. Patient Characteristics Before PSM

3.1.2. Comparison of OS and PFS Before PSM

3.1.3. Comparison of Treatment Efficacy Before PSM

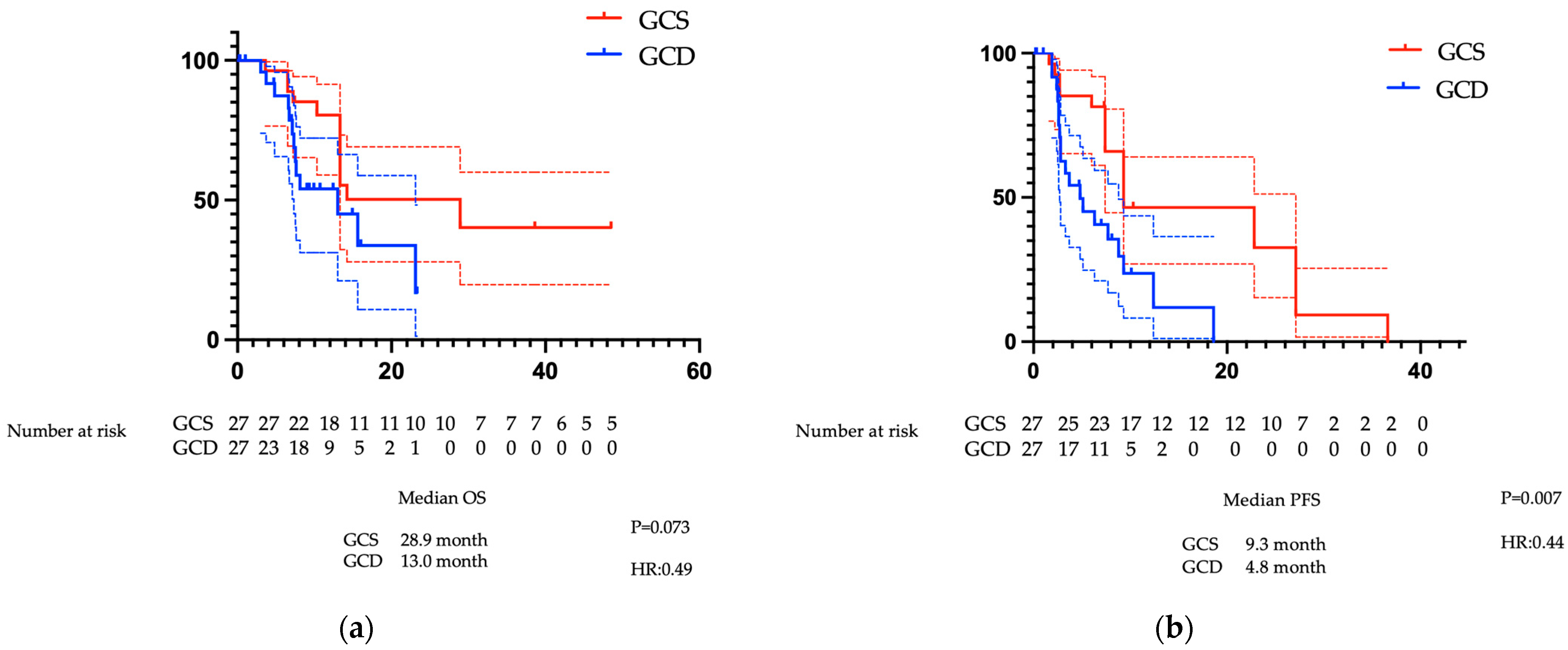

3.2. Analysis Results After PSM

3.2.1. Patient Characteristics After PSM

3.2.2. Comparison of PFS and OS After PSM

3.2.3. Comparison of Treatment Efficacy Following PSM

3.3. Adverse Events

3.4. Drug Costs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BTC | biliary tract cancer |

| CI | confidence interval |

| DCR | disease control rate |

| GC | gemcitabine plus cisplatin |

| GCD | gemcitabine plus cisplatin plus durvalumab |

| GCP | gemcitabine plus cisplatin plus pembrolizumab |

| GCS | gemcitabine plus cisplatin plus S-1 |

| HR | hazard ratio |

| ICI | immune checkpoint inhibitor |

| IrAE | immune-related adverse event |

| ORR | objective response rate |

| OS | overall survival |

| PFS | progression-free survival |

| PSM | propensity score matching |

References

- Valle, J.W.; Kelley, R.K.; Nervi, B.; Oh, D.Y.; Zhu, A.X. Biliary tract cancer. Lancet 2021, 397, 428–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banales, J.M.; Cardinale, V.; Carpino, G.; Marzioni, M.; Andersen, J.B.; Invernizzi, P.; Lind, G.E.; Folseraas, T.; Forbes, S.J.; Fouassier, L.; et al. Expert consensus document: Cholangiocarcinoma: Current knowledge and future perspectives consensus statement from the European Network for the Study of Cholangiocarcinoma (ENS-CCA). Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 13, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strijker, M.; Belkouz, A.; van der Geest, L.G.; van Gulik, T.M.; van Hooft, J.E.; de Meijer, V.E.; Haj Mohammad, N.; de Reuver, P.R.; Verheij, J.; de Vos-Geelen, J.; et al. Treatment and survival of resected and unresected distal cholangiocarcinoma: A nationwide study. Acta Oncol. 2019, 58, 1048–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alabraba, E.; Joshi, H.; Bird, N.; Griffin, R.; Sturgess, R.; Stern, N.; Sieberhagen, C.; Cross, T.; Camenzuli, A.; Davis, R.; et al. Increased multimodality treatment options has improved survival for Hepatocellular carcinoma but poor survival for biliary tract cancers remains unchanged. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 45, 1660–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spolverato, G.; Kim, Y.; Alexandrescu, S.; Marques, H.P.; Lamelas, J.; Aldrighetti, L.; Clark Gamblin, T.; Maithel, S.K.; Pulitano, C.; Bauer, T.W.; et al. Management and Outcomes of Patients with Recurrent Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma Following Previous Curative-Intent Surgical Resection. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2016, 23, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, J.; Wasan, H.; Palmer, D.H.; Cunningham, D.; Anthoney, A.; Maraveyas, A.; Madhusudan, S.; Iveson, T.; Hughes, S.; Pereira, S.P.; et al. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 1273–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, D.Y.; Ruth He, A.; Qin, S.; Chen, L.T.; Okusaka, T.; Vogel, A.; Kim, J.W.; Suksombooncharoen, T.; Ah Lee, M.; Kitano, M.; et al. Durvalumab plus Gemcitabine and Cisplatin in Advanced Biliary Tract Cancer. NEJM Evid. 2022, 1, EVIDoa2200015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, D.Y.; He, A.R.; Bouattour, M.; Okusaka, T.; Qin, S.; Chen, L.T.; Kitano, M.; Lee, C.K.; Kim, J.W.; Chen, M.H.; et al. Durvalumab or placebo plus gemcitabine and cisplatin in participants with advanced biliary tract cancer (TOPAZ-1): Updated overall survival from a randomised phase 3 study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 9, 694–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, R.K.; Ueno, M.; Yoo, C.; Finn, R.S.; Furuse, J.; Ren, Z.; Yau, T.; Klümpen, H.J.; Chan, S.L.; Ozaka, M.; et al. Pembrolizumab in combination with gemcitabine and cisplatin compared with gemcitabine and cisplatin alone for patients with advanced biliary tract cancer (KEYNOTE-966): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2023, 401, 1853–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, C.; Hyung, J.; Chan, S.L. Recent Advances in Systemic Therapy for Advanced Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. Liver Cancer 2024, 13, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioka, T.; Kanai, M.; Kobayashi, S.; Sakai, D.; Eguchi, H.; Baba, H.; Seo, S.; Taketomi, A.; Takayama, T.; Yamaue, H.; et al. Randomized phase III study of gemcitabine, cisplatin plus S-1 versus gemcitabine, cisplatin for advanced biliary tract cancer (KHBO1401- MITSUBA). J. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Sci. 2023, 30, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morizane, C.; Okusaka, T.; Mizusawa, J.; Katayama, H.; Ueno, M.; Ikeda, M.; Ozaka, M.; Okano, N.; Sugimori, K.; Fukutomi, A.; et al. Combination gemcitabine plus S-1 versus gemcitabine plus cisplatin for advanced/recurrent biliary tract cancer: The FUGA-BT (JCOG1113) randomized phase III clinical trial. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 1950–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Cancer Institute. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), version 4.0. Published 28 May 2009; Revised 14 June 2010. Available online: https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Eisenhauer, E.A.; Therasse, P.; Bogaerts, J.; Schwartz, L.H.; Sargent, D.; Ford, R.; Dancey, J.; Arbuck, S.; Gwyther, S.; Mooney, M.; et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur. J. Cancer 2009, 45, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vithayathil, M.; Khan, S.A. Current epidemiology of cholangiocarcinoma in Western countries. J. Hepatol. 2022, 77, 1690–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Tavolari, S.; Brandi, G. Cholangiocarcinoma: Epidemiology and risk factors. Liver Int. 2019, 39, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, A.B.; D’Angelica, M.I.; Abrams, T.; Abbott, D.E.; Ahmed, A.; Anaya, D.A.; Anders, R.; Are, C.; Bachini, M.; Binder, D.; et al. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Biliary Tract Cancers, Version 2.2023. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 2023, 21, 694–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, A.; Bridgewater, J.; Edeline, J.; Kelley, R.K.; Klümpen, H.J.; Malka, D.; Primrose, J.N.; Rimassa, L.; Stenzinger, A.; Valle, J.W.; et al. Biliary tract cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shroff, R.T.; Javle, M.M.; Xiao, L.; Kaseb, A.O.; Varadhachary, G.R.; Wolff, R.A.; Raghav, K.P.S.; Iwasaki, M.; Masci, P.; Ramanathan, R.K.; et al. Gemcitabine, Cisplatin, and nab-Paclitaxel for the Treatment of Advanced Biliary Tract Cancers: A Phase 2 Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol 2019, 5, 824–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelip, J.M.; Desrame, J.; Edeline, J.; Barbier, E.; Terrebonne, E.; Michel, P.; Perrier, H.; Dahan, L.; Bourgeois, V.; Akouz, F.K.; et al. Modified FOLFIRINOX Versus CISGEM Chemotherapy for Patients with Advanced Biliary Tract Cancer (PRODIGE 38 AMEBICA): A Randomized Phase II Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuah, B.; Goh, B.C.; Lee, S.C.; Soong, R.; Lau, F.; Mulay, M.; Dinolfo, M.; Lim, S.E.; Soo, R.; Furuie, T.; et al. Comparison of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of S-1 between Caucasian and East Asian patients. Cancer Sci. 2011, 102, 478–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Yang, Y. 146P A retrospective study of the efficacy of gemcitabine combined with capecitabine versus capecitabine alone for biliary tract cancer after curative resection. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, S1462–S1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.S.; Choi, Y.H.; Kim, J.Y.; Lee, M.H.; Paik, K.; Cho, I.R.; Kwon, W.I.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, I.S.; Lee, M.A.; et al. Comparison of 5-Fluorouracil/Leucovorin and Capecitabine as Adjuvant Therapies in Biliary Tract Cancer. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, 40, 2324–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, M.J.; Seal, B.; Princic, N.; Black, D.; Malangone-Monaco, E.; Azad, N.S.; Smoot, R.L. Real-World Analysis of Treatment Patterns, Healthcare Utilization, Costs, and Mortality Among People with Biliary Tract Cancers in the USA. Adv. Ther. 2022, 39, 5530–5545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Zhao, Y.; Shi, F.; Zhu, J.; Wu, J.; Huang, M.; Qiu, K. Cost–effectiveness analysis of immune checkpoint inhibitors as first-line therapy in advanced biliary tract cancer. Immunotherapy 2024, 16, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, C.X.; Faust, E.; Goldschmidt, D.; Webster, N.; Boscoe, A.N.; Macaulay, D.; Peters, M.L. Burden of illness for patients with cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: A retrospective claims analysis. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2021, 12, 658–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Registry, U.C.T. Phase III Study of Gemcitabine, Cisplatin Plus S-1 Combination Therapy Versus Gemcitabine, Cisplatin Plus Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Combination Therapy in Advanced Biliary Tract Cancer. 2023. Available online: https://center6.umin.ac.jp/cgi-open-bin/ctr_e/ctr_view.cgi?recptno=R000058983 (accessed on 5 December 2025).

| Characteristic | All Patients (n = 96) | GCS (n = 52) | GCD (n = 44) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male %) | 60 (62.5) | 37 (71) | 23 (52) | 0.0899 |

| Age, years | 66.5 (31–85) | 65 (31–84) | 68 (42–85) | 0.0437 * |

| Performance Status (0/1) | 91 (95%)/5 (5%) | 51 (98%)/1 (2%) | 40 (90%)/4 (9%) | 0.176 |

| Primary tumour site | 0.234 | |||

| Intrahepatic bile duct | 37 (38.5) | 20 (38.5) | 17 (38.6) | |

| Perihilar | 22 (22.9) | 14 (26.9) | 8 (18.2) | |

| Distal | 11 (11.4) | 7 (13.4) | 4 (9.1) | |

| Gall bladder | 24 (25.0) | 9 (17.3) | 15 (34.1) | |

| Ampullary | 2 (2.1) | 2 (3.9) | 0 (0) | |

| Stage I/II/III/IV | 3/8/13/72 | 3/8/7/34 | 0/0/6/38 | 0.0134 * |

| (3/8/13/75) | (6/15/13/65) | (0/0/13/86) | ||

| Recurrent | 16 (17) | 2 (4) | 14 (32) | 0.0002 * |

| Unresectable | 80 (83) | 50 (96) | 30 (68) | |

| Locally advanced | 29 (30) | 20 (38) | 9 (20) | 0.0555 |

| Metastatic | 67 (70) | 32 (62) | 35 (80) | |

| Ascites (Yes/No) | 12/84 | 4 (8)/48 (92) | 8 (18)/36 (82) | 0.13 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 72 (55–127) | 73 (66.5–89.3) | 69.5 (59.5–82.0) | 0.12 |

| mALBI (G1/2a/2b/3) | 30/20/33/45 | 13/11/20/8 | 17/9/11/37 | 0.43 |

| CEA (ng/mL) | 3.7 | 3.3 (2.35–6.5) | 3.65 (2.0–14.7) | 0.71 |

| CA19-9 (U/mL) | 301.5 (12.2–2332) | 197 (21.2–2382) | 349 (12.24–1217) | 0.87 |

| Complications (Diabetes, liver disease) (Yes/No) | 19 (20)/77 (80) | 13 (25)/39 (75) | 6 (14)/38 (86) | 0.24 |

| total number of chemotherapy cycles | 7 (2–22) | 14 (2–32) | 0.31 |

| GCS (n = 52) | GCD (n = 44) | |

|---|---|---|

| Complete response | 1 (1.9) | 0 |

| Partial response | 18 (34.6) | 7 (15.9) |

| Stable disease | 22 (42.3) | 16 (36.3) |

| Progressive disease | 8 (15.4) | 15 (34.0) |

| Not evaluable | 3 (5.8) | 6 (13.6) |

| Characteristic | All Patients (n = 54) | GCS (n = 27) | GCD (n = 27) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male %) | 24 (44.4) | 8 (29.5) | 16 (59.3) | 0.054 |

| Age, years | 63 (48–73) | 68 (48–73) | 65.5 (62.5–73) | 0.078 |

| Primary tumour site | 0.205 | |||

| Intrahepatic bile duct | 21 (38.8) | 8 (29.6) | 13 (48.1) | |

| Perihilar | 10 (18.5) | 4 (14.8) | 6 (22.2) | |

| Distal | 3 (5.5) | 1 (3.7) | 2 (7.4) | |

| Gall bladder | 18 (33.3) | 12 (44.4) | 6 (22.2) | |

| Ampullary | 2 (3.7) | 2 (7.4) | 0 (0) | |

| Stage I/II/III/IV | 0/0/11/43 (0/0/20/80) | 0/0/7/20 (0/0/26/74) | 0/0/4/23 (0/0/15/85) | 0.501 |

| Recurrent | 4 (8) | 6 (22) | 4 (15) | 0.728 |

| Unresectable | 48 (92) | 21 (78) | 23 (85) | |

| Locally advanced | 13 (25) | 6 (22) | 7 (26) | 1.000 |

| Metastatic | 41 (75) | 21 (78) | 20 (74) |

| GCS (n = 27) | GCD (n = 27) | |

|---|---|---|

| Complete response | 0 | 0 |

| Partial response | 8 (29.6) | 4 (14.8) |

| Stable disease | 9 (33.3) | 9 (33.3) |

| Progressive disease | 4 (14.8) | 12 (44.4) |

| Not evaluable | 6 (22.2) | 2 (7.4) |

| Conversion surgery | 5 (18.5) | 2 (7.4) |

| GCS (n = 52) | GCD (n = 44) | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All grade (%) | Grade3, 4 (%) | All grade (%) | Grade3, 4 (%) | All grade | Grade 3, 4 | |

| Any AE | 37 (84.1) | 24 (54.5) | 49 (94.2) | 29 (55.7) | 0.1783 | 1.0000 |

| Haematopoietic toxicity | ||||||

| Anaemia | 23 (52.3) | 11 (25.0) | 37 (71.2) | 14 (26.9) | 0.0899 | 1.0000 |

| Leukopenia | 12 (27.3) | 10 (22.7) | 23 (44.2) | 19 (36.5) | 0.0099 * | 0.0998 |

| Neutropenia | 10 (22.7) | 7 (15.9) | 25 (48.1) | 16 (30.8) | 0.0322 * | 0.1823 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 8 (18.2) | 5 (11.4) | 18 (34.6) | 9 (17.3) | 0.1060 | 0.5638 |

| Febrile neutropenia | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.9) | 1 (1.9) | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Non-haematopoietic toxicity | ||||||

| Constipation | 25 (56.8) | 0 | 16 (30.8) | 0 | 0.0132 * | |

| Loss of appetite | 14 (31.8) | 0 | 25 (48.1) | 0 | 0.1445 | |

| Nausea | 7 (15.9) | 0 | 16 (30.8) | 0 | 0.0998 | |

| Taste disturbance | 7 (15.9) | 0 | 13 (25.1) | 0 | 0.3206 | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 15 (34.1) | 1 (2.3) | 5 (9.6) | 1 (1.9) | 0.0049 * | 1.0000 |

| Fatigue/malaise | 16 (36.4) | 1 (2.3) | 38 (73.1) | 1 (1.9) | 0.0004 * | 1.0000 |

| Hand-Foot Syndrome | 0 | 0 | 8 (15.4) | 0 | 0.0070 * | |

| Oral mucositis | 3 (6.8) | 0 | 8 (15.4) | 0 | 0.2177 | |

| Diarrhoea | 0 | 0 | 4 (7.7) | 0 | 0.1224 | |

| Thrombosis | 3 (6.8) | 0 | 2 (3.8) | 0 | 0.6580 | |

| Stroke | 3 (6.8) | 2 (4.5) | 0 | 0 | 0.0927 | 0.2075 |

| Hypertension | 2 (4.5) | 1 (2.3) | 0 | 0 | 0.2075 | 0.4583 |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 1 (2.3) | 0 | 6 (11.5) | 0 | 0.1204 | |

| Rotatory vertigo | 1 (2.3) | 1 (2.3) | 0 | 0 | 0.4583 | 0.4583 |

| Hypokalaemia | 1 (2.3) | 1 (2.3) | 0 | 0 | 0.4583 | 0.4583 |

| Heart failure | 1 (2.3) | 1 (2.3) | 0 | 0 | 0.4583 | 0.4583 |

| Oedema | 1 (2.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.4583 | |

| Hypoglycaemia | 1 (2.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.4583 | |

| Hiccups | 1 (2.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.4583 | |

| Hyponatraemia | 0 | 0 | 2 (3.8) | 1 (1.9) | 0.4982 | 1.0000 |

| Anaphylactic shock | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.9) | 1 (1.9) | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| IrAE | ||||||

| Skin disorders | 6 (13.6) | 1 (2.3) | 0 | 0 | 0.0076 * | 0.4583 |

| IrAE nephritis | 1 (2.3) | 1 (2.3) | 0 | 0 | 0.4583 | 0.4583 |

| Pancreatitis | 1 (2.3) | 1 (2.3) | 0 | 0 | 0.4583 | 0.4583 |

| Elevated AST | 1 (2.3) | 1 (2.3) | 0 | 0 | 0.4583 | 0.4583 |

| Elevated ALT | 1 (2.3) | 1 (2.3) | 0 | 0 | 0.4583 | 0.4583 |

| Increased amylase | 1 (2.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.4583 | |

| Hyperthyroidism | 1 (2.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.4583 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Morita, Y.; Sugimoto, R.; Kurokawa, M.; Tanaka, Y.; Senju, T.; Ichimaru, T.; Lee, L.; Niina, Y.; Hisano, T.; Furukawa, M.; et al. Gemcitabine + Cisplatin + S-1 Treatment for Advanced Cholangiocarcinoma: Cost-Effective, with Better Progression-Free Survival Versus Standard Treatment with Gemcitabine + Cisplatin + Durvalumab. Cancers 2025, 17, 3971. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243971

Morita Y, Sugimoto R, Kurokawa M, Tanaka Y, Senju T, Ichimaru T, Lee L, Niina Y, Hisano T, Furukawa M, et al. Gemcitabine + Cisplatin + S-1 Treatment for Advanced Cholangiocarcinoma: Cost-Effective, with Better Progression-Free Survival Versus Standard Treatment with Gemcitabine + Cisplatin + Durvalumab. Cancers. 2025; 17(24):3971. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243971

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorita, Yusuke, Rie Sugimoto, Miho Kurokawa, Yuki Tanaka, Takeshi Senju, Toshimitsu Ichimaru, Lingaku Lee, Yusuke Niina, Terumasa Hisano, Masayuki Furukawa, and et al. 2025. "Gemcitabine + Cisplatin + S-1 Treatment for Advanced Cholangiocarcinoma: Cost-Effective, with Better Progression-Free Survival Versus Standard Treatment with Gemcitabine + Cisplatin + Durvalumab" Cancers 17, no. 24: 3971. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243971

APA StyleMorita, Y., Sugimoto, R., Kurokawa, M., Tanaka, Y., Senju, T., Ichimaru, T., Lee, L., Niina, Y., Hisano, T., Furukawa, M., Sugimachi, K., & Tanaka, M. (2025). Gemcitabine + Cisplatin + S-1 Treatment for Advanced Cholangiocarcinoma: Cost-Effective, with Better Progression-Free Survival Versus Standard Treatment with Gemcitabine + Cisplatin + Durvalumab. Cancers, 17(24), 3971. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243971