Surgical Management of Locally Advanced and Metastatic Gallbladder Cancer

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Advances in Systemic Therapy for Advanced Biliary Cancers

| Trial Enrollment Years | Patient Population | Treatment Group (n) | Control Group (n) | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABC-02 [26] 2002–2008 | Unresectable, recurrent, or metastatic biliary tract cancers | Gemcitabine + cisplatin (204) | Gemcitabine (206) | Treatment group with improved median OS (11.7 vs. 8.1 months) and PFS (8.0 vs. 5.0 months) |

| SWOG S1815 [27] 2018–2021 | Unresectable, locally advanced, or metastatic biliary tract cancers | Gemcitabine + cisplatin + nab-paclitaxel (294) | Gemcitabine + cisplatin (147) | No difference in OS or PFS between groups |

| POLCAGB [32] 2016–2024 | Unresectable locally advanced gallbladder cancers | Gemcitabine + radiotherapy followed by gemcitabine + cisplatin (60) | Gemcitabine + cisplatin (64) | Treatment group with improved median OS (21.8 vs. 10.1 months) and R0 resection rate (51.6% vs. 29.7%) |

| TOPAZ-1 [28] 2019–2020 | Unresectable, locally advanced, or metastatic biliary tract cancers | Gemcitabine + cisplatin + durvalumab (341) | Gemcitabine + cisplatin + placebo (344) | Treatment group with improved median OS (12.9 vs. 11.3 months) and PFS (7.2 vs. 5.7 months) |

| KEYNOTE-966 [30] 2019–2021 | Unresectable, locally advanced, or metastatic biliary tract cancers | Gemcitabine + cisplatin + pembrolizumab (533) | Gemcitabine + cisplatin + placebo (536) | Treatment group with improved median OS (12.7 vs. 10.9 months) |

| ABC-06 [31] 2014–2018 | Locally advanced or metastatic biliary tract cancers that progressed on gemcitabine and cisplatin therapy | Active symptom control + FOLFOX (oxaliplatin + L-folinic acid + fluorouracil) (81) | Active symptom control alone (81) | Treatment group with improved median OS (6.2 vs. 5.3 months) |

| BILCAP [33] 2006–2014 | Resected biliary tract cancers | Adjuvant capecitabine (210) | Observation alone (220) | Treatment group with improved median OS (53 vs. 36 months) and RFS (25.9 vs. 17.4 months) in per-protocol analysis |

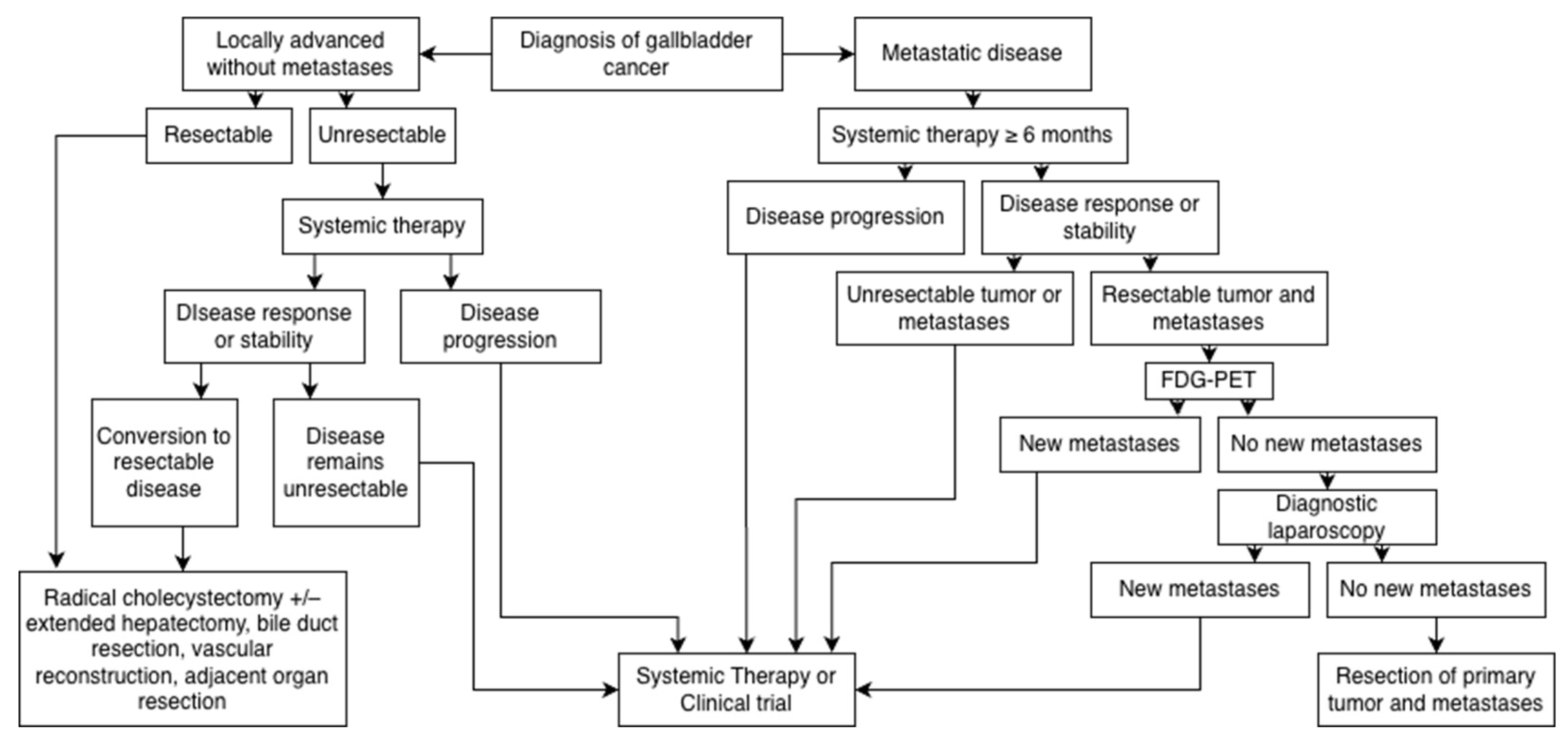

3. Surgical Management of Locally Advanced Disease

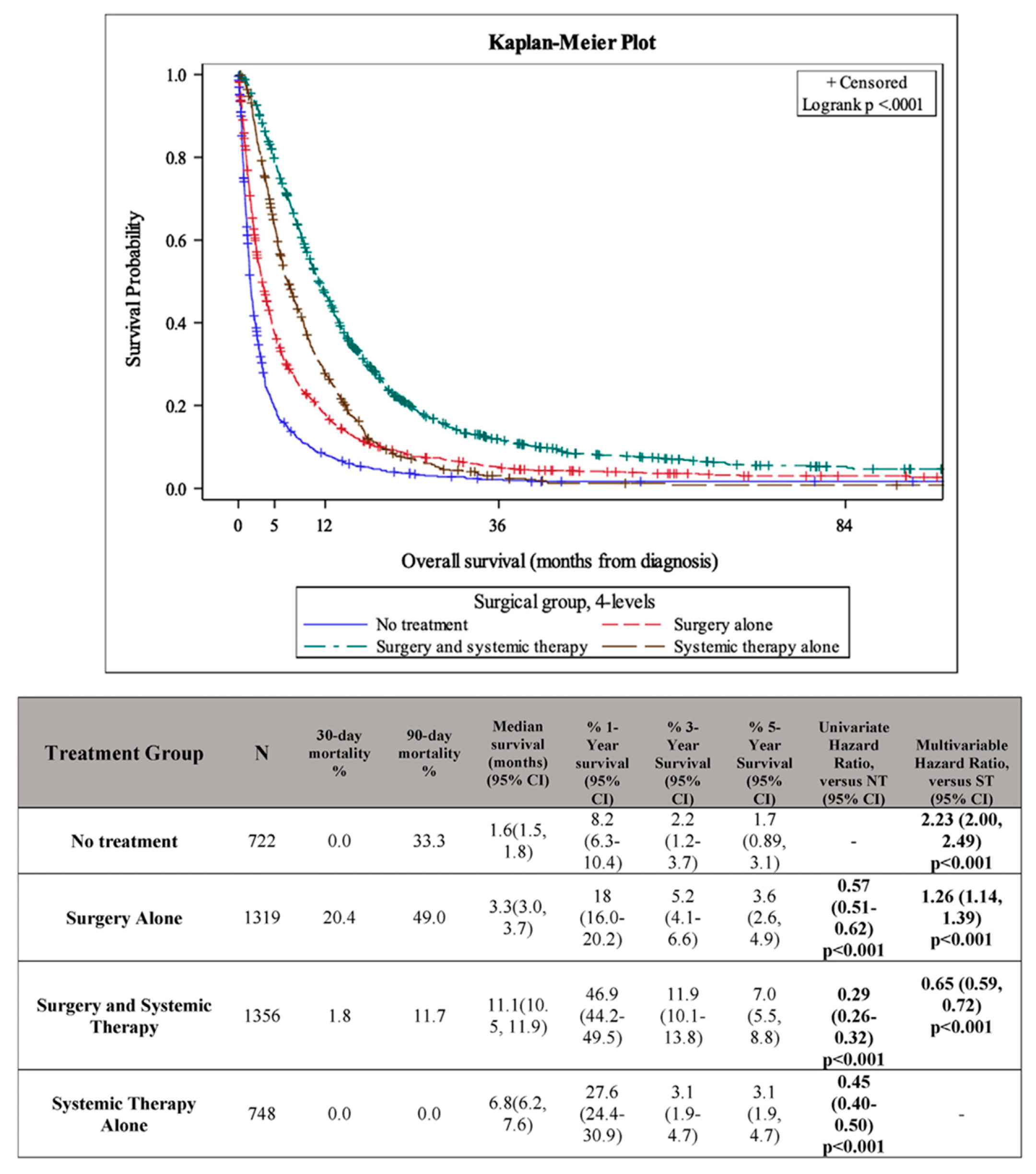

4. The Role of Surgery in Metastatic Disease

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GBC | Gallbladder cancer |

| AJCC | American Joint Committee on Cancer |

| FLR | Future liver remnant |

| PVE | Portal vein embolization |

| LVD | Liver venous deprivation |

| ALPPS | Associated liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy |

| FGF | Fibroblast growth factor |

| FGFR | Fibroblast growth factor receptor |

| dMMR | Mismatch repair-deficient |

References

- Nitsche, U.; Stöß, C.; Stecher, L.; Wilhelm, D.; Friess, H.; Ceyhan, G.O. Meta-Analysis of Outcomes Following Resection of the Primary Tumour in Patients Presenting with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Br. J. Surg. 2018, 105, 784–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, N.; Gaskins, J.; Martin, R.C.G. Surgical Outcomes in Stage IV Pancreatic Cancer with Liver Metastasis Current Evidence and Future Directions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Surgical Resection. Cancers 2025, 17, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuthaluru, S.; Sharma, P.; Chowdhury, S.; Are, C. Global Epidemiological Trends and Variations in the Burden of Gallbladder Cancer. J. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 128, 980–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Du, S.; Liu, X.; Niu, W.; Song, K.; Yu, J. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Gallbladder and Biliary Tract Cancer, 1990 to 2021 and Predictions to 2045: An Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2025, 29, 101968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Kratzer, T.B.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2025, 75, 10–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randi, G.; Franceschi, S.; La Vecchia, C. Gallbladder Cancer Worldwide: Geographical Distribution and Risk Factors. Int. J. Cancer 2006, 118, 1591–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, D.; Yang, J.; Xu, F.; Huang, Q.; Bai, L.; Wei, Y.; Kaaya, R.E.; Wang, S.; Lyu, J. Prognostic Factors in Patients with Gallbladder Adenocarcinoma Identified Using Competing-Risks Analysis: A Study of Cases in the SEER Database. Medicine 2020, 99, e21322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Ammannagari, N.; Pokuri, V.K.; Kuvshinoff, B.; Groman, A.; LeVea, C.M.; Iyer, R. Clinicopathological Characteristics and Outcomes of Rare Histologic Subtypes of Gallbladder Cancer over Two Decades: A Population-Based Study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, A.; Capanu, M.; Abou-Alfa, G.K.; Huitzil, D.; Jarnagin, W.; Fong, Y.; D’Angelica, M.; DeMatteo, R.P.; Blumgart, L.H.; O’Reilly, E.M. Gallbladder Cancer (GBC): 10-Year Experience at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Centre (MSKCC). J. Surg. Oncol. 2008, 98, 485–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roa, J.C.; García, P.; Kapoor, V.K.; Maithel, S.K.; Javle, M.; Koshiol, J. Gallbladder Cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2022, 8, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seretis, C.; Lagoudianakis, E.; Gemenetzis, G.; Seretis, F.; Pappas, A.; Gourgiotis, S. Metaplastic Changes in Chronic Cholecystitis: Implications for Early Diagnosis and Surgical Intervention to Prevent the Gallbladder Metaplasia-Dysplasia-Carcinoma Sequence. J. Clin. Med. Res. 2014, 6, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, K.; Mohapatra, T.; Das, P.; Misra, M.C.; Gupta, S.D.; Ghosh, M.; Kabra, M.; Bansal, V.K.; Kumar, S.; Sreenivas, V.; et al. Sequential Occurrence of Preneoplastic Lesions and Accumulation of Loss of Heterozygosity in Patients with Gallbladder Stones Suggest Causal Association with Gallbladder Cancer. Ann. Surg. 2014, 260, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamisawa, T.; Kuruma, S.; Chiba, K.; Tabata, T.; Koizumi, S.; Kikuyama, M. Biliary Carcinogenesis in Pancreaticobiliary Maljunction. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 52, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®): Biliary Tract Cancers. Available online: www.nccn.org (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Aloia, T.A.; Járufe, N.; Javle, M.; Maithel, S.K.; Roa, J.C.; Adsay, V.; Coimbra, F.J.F.; Jarnagin, W.R. Gallbladder Cancer: Expert Consensus Statement. HPB 2015, 17, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.K.; Kalayarasan, R.; Javed, A.; Gupta, N.; Nag, H.H. The Role of Staging Laparoscopy in Primary Gall Bladder Cancer—An Analysis of 409 Patients: A Prospective Study to Evaluate the Role of Staging Laparoscopy in the Management of Gallbladder Cancer. Ann. Surg. 2013, 258, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dooren, M.; de Savornin Lohman, E.A.J.; Brekelmans, E.; Vissers, P.A.J.; Erdmann, J.I.; Braat, A.E.; Hagendoorn, J.; Daams, F.; van Dam, R.M.; de Boer, M.T.; et al. The Diagnostic Value of Staging Laparoscopy in Gallbladder Cancer: A Nationwide Cohort Study. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 21, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bitter, T.J.J.; de Reuver, P.R.; de Savornin Lohman, E.A.J.; Kroeze, L.I.; Vink-Börger, M.E.; van Vliet, S.; Simmer, F.; von Rhein, D.; Jansen, E.A.M.; Verheij, J.; et al. Comprehensive Clinicopathological and Genomic Profiling of Gallbladder Cancer Reveals Actionable Targets in Half of Patients. npj Precis. Onc 2022, 6, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, M.B.; Edge, S.B.; Greene, F.L.; Byrd, D.R.; Brookland, R.K.; Washington, M.K.; Gershenwald, J.E.; Compton, C.C.; Hess, K.R.; Sullivan, D.C.; et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 8th ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Giannis, D.; Cerullo, M.; Moris, D.; Shah, K.N.; Herbert, G.; Zani, S.; Blazer, D.G.; Allen, P.J.; Lidsky, M.E. Validation of the 8th Edition American Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC) Gallbladder Cancer Staging System: Prognostic Discrimination and Identification of Key Predictive Factors. Cancers 2021, 13, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Zhao, B.; Li, Y.; Qi, D.; Wang, D. Modification of the 8th American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging System for Gallbladder Carcinoma to Improve Prognostic Precision. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo, J.O.; Rubio, B.; Fodor, M.; Orlandi, L.; Yáñez, M.; Gamargo, C.; Ahumada, M. A Phase II Study of Gemcitabine in Gallbladder Carcinoma. Ann. Oncol. 2001, 12, 1403–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckel, F.; Schmid, R.M. Chemotherapy in Advanced Biliary Tract Carcinoma: A Pooled Analysis of Clinical Trials. Br. J. Cancer 2007, 96, 896–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheithauer, W. Review of Gemcitabine in Biliary Tract Carcinoma. Semin. Oncol. 2002, 29 (Suppl. S20), 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, J.; Wasan, H.; Palmer, D.H.; Cunningham, D.; Anthoney, A.; Maraveyas, A.; Madhusudan, S.; Iveson, T.; Hughes, S.; Pereira, S.P.; et al. Cisplatin plus Gemcitabine versus Gemcitabine for Biliary Tract Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 1273–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shroff, R.T.; King, G.; Colby, S.; Scott, A.J.; Borad, M.J.; Goff, L.; Matin, K.; Mahipal, A.; Kalyan, A.; Javle, M.M.; et al. SWOG S1815: A Phase III Randomized Trial of Gemcitabine, Cisplatin, and Nab-Paclitaxel Versus Gemcitabine and Cisplatin in Newly Diagnosed, Advanced Biliary Tract Cancers. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, D.-Y.; Ruth He, A.; Qin, S.; Chen, L.-T.; Okusaka, T.; Vogel, A.; Kim, J.W.; Suksombooncharoen, T.; Ah Lee, M.; Kitano, M.; et al. Durvalumab plus Gemcitabine and Cisplatin in Advanced Biliary Tract Cancer. NEJM Evid. 2022, 1, EVIDoa2200015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, D.-Y.; He, A.R.; Bouattour, M.; Okusaka, T.; Qin, S.; Chen, L.-T.; Kitano, M.; Lee, C.; Kim, J.W.; Chen, M.-H.; et al. Durvalumab or Placebo plus Gemcitabine and Cisplatin in Participants with Advanced Biliary Tract Cancer (TOPAZ-1): Updated Overall Survival from a Randomised Phase 3 Study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 9, 694–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, R.K.; Ueno, M.; Yoo, C.; Finn, R.S.; Furuse, J.; Ren, Z.; Yau, T.; Klümpen, H.-J.; Chan, S.L.; Ozaka, M.; et al. Pembrolizumab in Combination with Gemcitabine and Cisplatin Compared with Gemcitabine and Cisplatin Alone for Patients with Advanced Biliary Tract Cancer (KEYNOTE-966): A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet 2023, 401, 1853–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamarca, A.; Palmer, D.H.; Wasan, H.S.; Ross, P.J.; Ma, Y.T.; Arora, A.; Falk, S.; Gillmore, R.; Wadsley, J.; Patel, K.; et al. Second-Line FOLFOX Chemotherapy versus Active Symptom Control for Advanced Biliary Tract Cancer (ABC-06): A Phase 3, Open-Label, Randomised, Controlled Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 690–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engineer, R.; Goel, M.; Ostwal, V.; Patkar, S.; Gudi, S.; Ramaswamy, A.; Kannan, S.; Shetty, N.; Gala, K.; Agrawal, A.; et al. A Phase III Randomized Clinical Trial Evaluating Perioperative Therapy (Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy versus Chemoradiotherapy) in Locally Advanced Gallbladder Cancers (POLCAGB). J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43 (Suppl. 16), 4007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primrose, J.N.; Fox, R.P.; Palmer, D.H.; Malik, H.Z.; Prasad, R.; Mirza, D.; Anthony, A.; Corrie, P.; Falk, S.; Finch-Jones, M.; et al. Capecitabine Compared with Observation in Resected Biliary Tract Cancer (BILCAP): A Randomised, Controlled, Multicentre, Phase 3 Study. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, H.; Ji, J.; Li, S.; Lai, J.; Wei, G.; Wu, J.; Chen, W.; Xie, W.; Wang, S.; Qiao, L.; et al. Adjuvant Chemoradiation and Immunotherapy for Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma and Gallbladder Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2025, 11, 1021–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horgan, A.M.; Amir, E.; Walter, T.; Knox, J.J. Adjuvant Therapy in the Treatment of Biliary Tract Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JCO 2012, 30, 1934–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Kwon, W.; Han, Y.; Kim, J.R.; Kim, S.-W.; Jang, J.-Y. Optimal Extent of Surgery for Early Gallbladder Cancer with Regard to Long-Term Survival: A Meta-Analysis. J. Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat. Sci. 2018, 25, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.-D.; Li, J.-J.; Liu, W.; Qu, Q.; Hong, T.; Xu, X.-Q.; Li, B.-L.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, H.-T. Surgical Procedure Determination Based on Tumor-Node-Metastasis Staging of Gallbladder Cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 4620–4626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodin, K.E.; Goins, S.; Kramer, R.; Eckhoff, A.M.; Herbert, G.; Shah, K.N.; Allen, P.J.; Nussbaum, D.P.; Blazer, D.G.; Zani, S.; et al. Simple versus Radical Cholecystectomy and Survival for Pathologic Stage T1B Gallbladder Cancer. HPB 2024, 26, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirban, A.M.; Rivera, B.; Kawahara, W.; Mellado, S.; Niakosari, M.; Okuno, M.; Panettieri, E.; De Bellis, M.; Kristjanpoller, W.; Merlo, I.; et al. Advanced Gallbladder Cancer (T3 and T4): Insights from an International Multicenter Study. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2025, 29, 102080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balakrishnan, A.; Barmpounakis, P.; Demiris, N.; Jah, A.; Spiers, H.V.M.; Talukder, S.; Martin, J.L.; Gibbs, P.; Harper, S.J.F.; Huguet, E.L.; et al. Surgical Outcomes of Gallbladder Cancer: The OMEGA Retrospective, Multicentre, International Cohort Study. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 59, 101951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsui, S.; Tanioka, T.; Nakajima, K.; Saito, T.; Kato, S.; Tomii, C.; Hasegawa, F.; Muramatsu, S.; Kaito, A.; Ito, K. Surgical and Oncological Outcomes of Wedge Resection Versus Segment 4b + 5 Resection for T2 and T3 Gallbladder Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2023, 27, 1954–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghidini, M.; Petrelli, F.; Paccagnella, M.; Salati, M.; Bergamo, F.; Ratti, M.; Soldà, C.; Galassi, B.; Garrone, O.; Rovatti, M.; et al. Prognostic Factors and Survival Outcomes in Resected Biliary Tract Cancers: A Multicenter Retrospective Analysis. Cancers 2025, 17, 2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelica, M.; Dalal, K.M.; DeMatteo, R.P.; Fong, Y.; Blumgart, L.H.; Jarnagin, W.R. Analysis of the Extent of Resection for Adenocarcinoma of the Gallbladder. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2009, 16, 806–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuipers, H.; de Savornin Lohman, E.A.J.; van Dooren, M.; Braat, A.E.; Daams, F.; van Dam, R.; Erdmann, J.I.; Hagendoorn, J.; Hoogwater, F.J.H.; Groot Koerkamp, B.; et al. Extended Resections for Advanced Gallbladder Cancer: Results from a Nationwide Cohort Study. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 28, 835–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Kim, C.Y.; Park, E.K.; Hur, Y.H.; Koh, Y.S.; Kim, H.J.; Cho, C.K. Volumetric Analysis and Indocyanine Green Retention Rate at 15 Min as Predictors of Post-hepatectomy Liver Failure. HPB 2015, 17, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, T.; Gilg, S.; Böcker, J.; Wagner, K.C.; Vali, M.; Engstrand, J.; Kern, A.; Sturesson, C.; Oldhafer, K.J.; Sparrelid, E. Impact of the Future Liver Remnant Volume before Major Hepatectomy. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 50, 108660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagino, M.; Kamiya, J.; Nishio, H.; Ebata, T.; Arai, T.; Nimura, Y. Two Hundred Forty Consecutive Portal Vein Embolizations Before Extended Hepatectomy for Biliary Cancer: Surgical Outcome and Long-Term Follow-Up. Ann. Surg. 2006, 243, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arntz, P.J.W.; Deroose, C.M.; Marcus, C.; Sturesson, C.; Panaro, F.; Erdmann, J.; Manevska, N.; Moadel, R.; de Geus-Oei, L.-F.; Bennink, R.J. Joint EANM/SNMMI/IHPBA Procedure Guideline for [99mTc]Tc-Mebrofenin Hepatobiliary Scintigraphy SPECT/CT in the Quantitative Assessment of the Future Liver Remnant Function. HPB 2023, 25, 1131–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieslak, K.P.; Bennink, R.J.; de Graaf, W.; van Lienden, K.P.; Besselink, M.G.; Busch, O.R.C.; Gouma, D.J.; van Gulik, T.M. Measurement of Liver Function Using Hepatobiliary Scintigraphy Improves Risk Assessment in Patients Undergoing Major Liver Resection. HPB 2016, 18, 773–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abulkhir, A.; Limongelli, P.; Healey, A.J.; Damrah, O.; Tait, P.; Jackson, J.; Habib, N.; Jiao, L.R. Preoperative Portal Vein Embolization for Major Liver Resection: A Meta-Analysis. Ann. Surg. 2008, 247, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebata, T.; Yokoyama, Y.; Igami, T.; Sugawara, G.; Takahashi, Y.; Nagino, M. Portal Vein Embolization before Extended Hepatectomy for Biliary Cancer: Current Technique and Review of 494 Consecutive Embolizations. Dig. Surg. 2012, 29, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, P.; Vien, P.; Kessler, J.; Lafaro, K.; Wei, A.; Melstrom, L.G. Augmenting the Future Liver Remnant Prior to Major Hepatectomy: A Review of Options on the Menu. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2025, 32, 5694–5709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozkurt, E.; Sijberden, J.P.; Kasai, M.; Hilal, M.A. Efficacy and Perioperative Safety of Different Future Liver Remnant Modulation Techniques: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. HPB 2024, 26, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, T.-R.; Liu, F.; Hu, H.-J.; Regmi, P.; Ma, W.-J.; Yang, Q.; Jin, Y.-W.; Li, F.-Y. The Role of Extra-Hepatic Bile Duct Resection in the Surgical Management of Gallbladder Carcinoma. A First Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 48, 482–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishio, H.; Ebata, T.; Yokoyama, Y.; Igami, T.; Sugawara, G.; Nagino, M. Gallbladder Cancer Involving the Extrahepatic Bile Duct Is Worthy of Resection. Ann. Surg. 2011, 253, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, H.; Endo, I.; Sugita, M.; Masunari, H.; Fujii, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Misuta, K.; Sekido, H.; Togo, S. Hepatic Resection Combined with Portal Vein or Hepatic Artery Reconstruction for Advanced Carcinoma of the Hilar Bile Duct and Gallbladder. World J. Surg. 2003, 27, 1137–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajibandeh, S.; Hajibandeh, S.; Raza, S.S.; Bartlett, D.C.; Chatzizacharias, N.; Dasari, B.V.M.; Roberts, K.J.; Marudanayagam, R.; Sutcliffe, R.P. Short-Term and Long-Term Outcomes of Hepatopancreatoduodenectomy for Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma and Gallbladder Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis with Meta-Regression. Surgery 2025, 186, 109593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, T.; Ebata, T.; Yokoyama, Y.; Igami, T.; Yamaguchi, J.; Onoe, S.; Watanabe, N.; Ando, M.; Nagino, M. Major Hepatectomy with or without Pancreatoduodenectomy for Advanced Gallbladder Cancer. Br. J. Surg. 2019, 106, 626–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zhang, X.; Hu, X.; Ren, H.; Wu, S.; Wu, J.; Wu, G.; Si, X.; Wang, B. Survival Analysis of Patients with Primary Gallbladder Cancer from 2010 to 2015: A Retrospective Study Based on SEER Data. Medicine 2020, 99, e22292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Liao, Z.; Sun, C.; Chen, Z. Impact of Primary Tumor Resection on Survival of Patients with Metastatic Gallbladder Carcinoma: A Population-Based, Propensity-Matched Study. Med. Sci. Monit. 2022, 28, e934447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nekarakanti, P.; Sugumaran, K.; Nag, H. Surgery versus No Surgery in Stage IV Gallbladder Carcinoma: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. Turk. J. Surg. 2023, 39, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patkar, S.; Patel, S.; Kazi, M.; Goel, M. Radical Surgery for Stage IV Gallbladder Cancers: Treatment Strategies in Patients with Limited Metastatic Burden. Ann. Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surg. 2023, 27, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casabianca, A.S.; Tsagkalidis, V.; Burchard, P.R.; Chacon, A.; Melucci, A.; Reitz, A.; Swift, D.A.; McCook, A.A.; Switchenko, J.M.; Shah, M.M.; et al. R. Surgery in Combination with Systemic Chemotherapy Is Associated with Improved Survival in Stage IV Gallbladder Cancer. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 48, 2448–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, A.; Shimizu, H.; Ohtsuka, M.; Yoshidome, H.; Yoshitomi, H.; Furukawa, K.; Takeuchi, D.; Takayashiki, T.; Kimura, F.; Miyazaki, M. Surgical Resection after Downsizing Chemotherapy for Initially Unresectable Locally Advanced Biliary Tract Cancer: A Retrospective Single-Center Study. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2013, 20, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakeem, A.R.; Papoulas, M.; Menon, K.V. The Role of Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy or Chemoradiotherapy for Advanced Gallbladder Cancer—A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 45, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creasy, J.M.; Goldman, D.A.; Dudeja, V.; Lowery, M.A.; Cercek, A.; Balachandran, V.P.; Allen, P.J.; DeMatteo, R.P.; Kingham, P.T.; D’Angelica, M.I.; et al. Systemic Chemotherapy Combined with Resection for Locally Advanced Gallbladder Carcinoma: Surgical and Survival Outcomes. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2017, 224, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Yan, J.; Ye, Y.; Yang, C.; Chen, Z.; Lin, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, R. Efficacy and Conversion Outcome of Chemotherapy Combined with PD-1 Inhibitor for Patients with Unresectable or Recurrent Gallbladder Carcinoma: A Real-World Exploratory Study. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2025, 23, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Li, Z.; Li, K.; Li, G.; Li, G.; Zhao, Y. Neoadjuvant Radiotherapy Combined with Targeted and Immune Therapies Achieves a Pathological Complete Response in Borderline Resectable Gallbladder Cancer: A Case Report and Literature Review. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlandi, E.; Toscani, I.; Trubini, S.; Schena, A.; Palladino, M.A.; Anselmi, E.; Vecchia, S.; Romboli, A.; Giuffrida, M. Evolving Approaches in Advanced Gallbladder Cancer with Complete Pathological Response Using Chemo-immunotherapy: A Case Report. Oncol. Lett. 2024, 28, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Tu, Z.; Ye, C.; Cai, H.; Yang, S.; Chen, X.; Tu, J. Site-Specific Metastases of Gallbladder Adenocarcinoma and Their Prognostic Value for Survival: A SEER-Based Study. BMC Surg. 2021, 21, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Liu, H.; Liu, Z.; Li, K.; Qin, R.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, Z.; Gao, Q.; Pan, C.; et al. FGF19 and FGFR4 Promotes the Progression of Gallbladder Carcinoma in an Autocrine Pathway Dependent on GPBAR1-cAMP-EGR1 Axis. Oncogene 2021, 40, 4941–4953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, A.; Sahai, V.; Hollebecque, A.; Vaccaro, G.M.; Melisi, D.; Al Rajabi, R.M.; Paulson, A.S.; Borad, M.J.; Gallinson, D.; Murphy, A.G.; et al. An Open-Label Study of Pemigatinib in Cholangiocarcinoma: Final Results from FIGHT-202☆. ESMO Open 2024, 9, 103488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, L.; Meric-Bernstam, F.; Hollebecque, A.; Valle, J.W.; Morizane, C.; Karasic, T.B.; Abrams, T.A.; Furuse, J.; Kelley, R.K.; Cassier, P.A.; et al. Futibatinib for FGFR2-Rearranged Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekaii-Saab, T.S.; Yaeger, R.; Spira, A.I.; Pelster, M.S.; Sabari, J.K.; Hafez, N.; Barve, M.; Velastegui, K.; Yan, X.; Shetty, A.; et al. Adagrasib in Advanced Solid Tumors Harboring a KRASG12C Mutation. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 4097–4106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cercek, A.; Foote, M.B.; Rousseau, B.; Smith, J.J.; Shia, J.; Sinopoli, J.; Weiss, J.; Lumish, M.; Temple, L.; Patel, M.; et al. Nonoperative Management of Mismatch Repair–Deficient Tumors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 2297–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, Y.-N.; Kim, S.J.; Jun, S.-Y.; Yoo, C.; Kim, K.-P.; Lee, J.H.; Hwang, D.W.; Hwang, S.; Lee, S.S.; Hong, S.-M. Expression of HER2 and Mismatch Repair Proteins in Surgically Resected Gallbladder Adenocarcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malka, D.; Borbath, I.; Lopes, A.; Couch, D.; Jimenez, M.; Vandamme, T.; Valle, J.W.; Wason, J.; Ambrose, E.; Dewever, L.; et al. Molecular Targeted Maintenance Therapy versus Standard of Care in Advanced Biliary Cancer: An International, Randomised, Controlled, Open-Label, Phase III Umbrella Trial (SAFIR-ABC10-Precision Medicine). ESMO Open 2025, 10, 104540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangat, P.K.; Halabi, S.; Bruinooge, S.S.; Garrett-Mayer, E.; Alva, A.; Janeway, K.A.; Stella, P.J.; Voest, E.; Yost, K.J.; Perlmutter, J.; et al. Rationale and Design of the Targeted Agent and Profiling Utilization Registry Study. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2018, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Available online: www.clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 24 September 2025).

| Trial ID | Patient Population | Treatment | Comparator (If Applicable) | Anticipated Completion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT06712420 (NEOGB) | Locally advanced GBC | Neoadjuvant gemcitabine + cisplatin followed by resection | Upfront resection | 2028 |

| NCT02170090 (ACTICCA-1) | Resected biliary tract cancers | Adjuvant gemcitabine + cisplatin | Adjuvant capecitabine | 2025 |

| NCT06591520 | Biliary tract cancers | Gemcitabine + cisplatin + AK112 (PD-1/VEGF inhibitor) | Gemcitabine + cisplatin + durvalumab | 2027 |

| NCT06282575 | HER2-positive locally advanced or metastatic biliary tract cancers | Zanidatamab (HER2 inhibitor) + gemcitabine + cisplatin +/− durvalumab or pembrolizumab | Gemcitabine + cisplatin +/− durvalumab or pembrolizumab | 2030 |

| NCT04526106 | Unresectable or metastatic solid organ tumors with FGFR2 mutations | RLY-4008 (FGFR2 inhibitor) | 2027 | |

| NCT06607185 | Locally advanced or metastatic solid organ tumors with KRAS mutations | LY4066434 (pan-KRAS inhibitor) | 2030 | |

| NCT05615818 (SAFIR-ABC10) | Locally advanced or metastatic biliary tract cancers with targetable mutations | Gemcitabine + cisplatin +/− durvalumab or pembrolizumab, followed by therapy matched to specific mutation | Gemcitabine + cisplatin +/− durvalumab or pembrolizumab | 2028 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Breitenbach, M.; Burchard, P.; Kothari, V.; Carpizo, D. Surgical Management of Locally Advanced and Metastatic Gallbladder Cancer. Cancers 2025, 17, 3952. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243952

Breitenbach M, Burchard P, Kothari V, Carpizo D. Surgical Management of Locally Advanced and Metastatic Gallbladder Cancer. Cancers. 2025; 17(24):3952. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243952

Chicago/Turabian StyleBreitenbach, Mitchell, Paul Burchard, Veer Kothari, and Darren Carpizo. 2025. "Surgical Management of Locally Advanced and Metastatic Gallbladder Cancer" Cancers 17, no. 24: 3952. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243952

APA StyleBreitenbach, M., Burchard, P., Kothari, V., & Carpizo, D. (2025). Surgical Management of Locally Advanced and Metastatic Gallbladder Cancer. Cancers, 17(24), 3952. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243952