From Microbiota to Cancer: Role of Extracellular Vesicles in Gut–Lung Axis

Simple Summary

Abstract

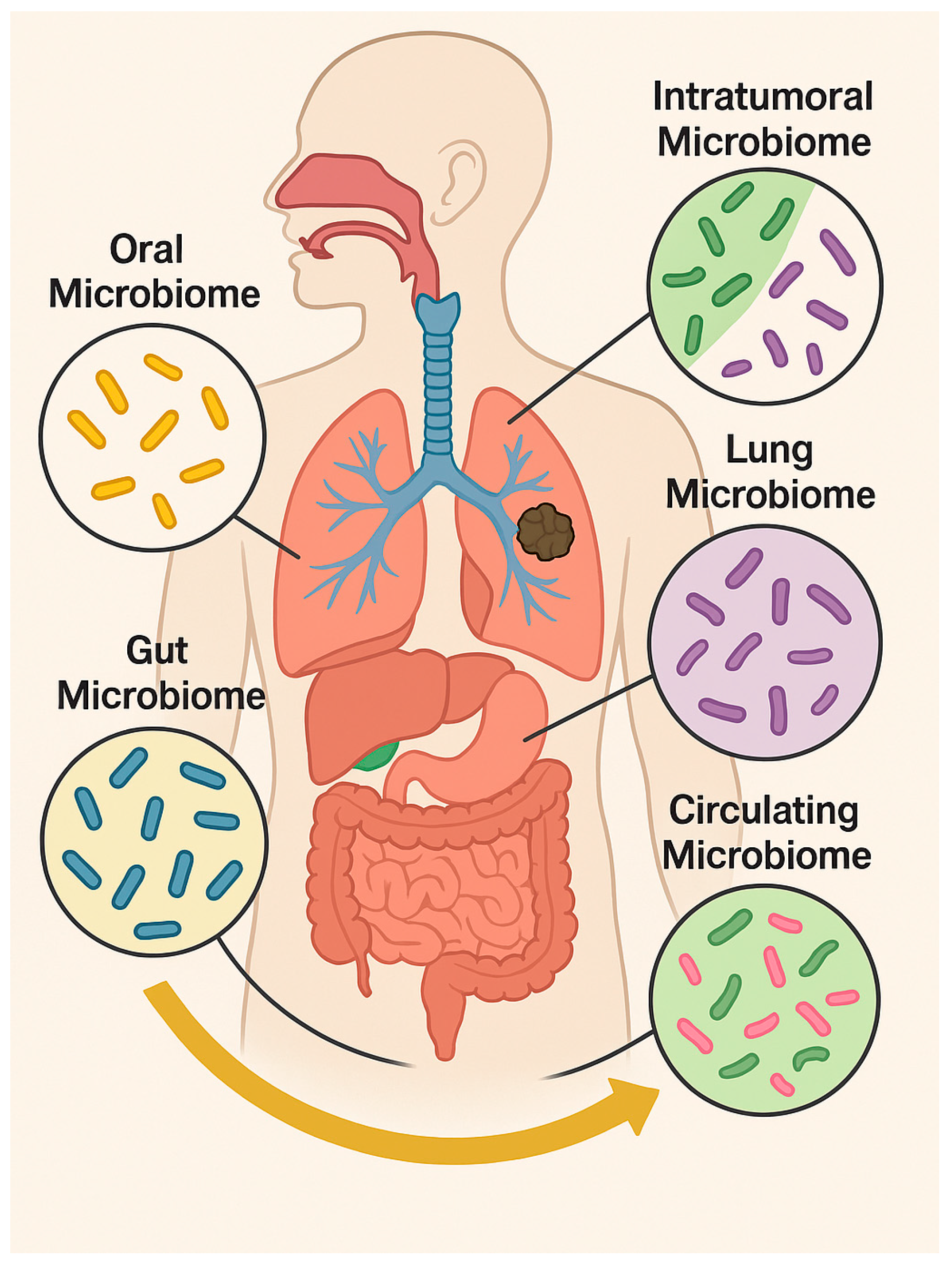

1. Introduction

2. Lung Cancer and the Gastrointestinal Microbiota: The Gut–Lung Axis

3. Risk Factors: Pollution, Lifestyle, and Inflammation

4. Extracellular Vesicles in Lung Cancer: Host and Bacterial Contributions

4.1. Tumor-Derived EVs (tEVs) and Their Roles in Lung Cancer Progression

4.2. Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles: Origin, Composition, and Impact on Lung Cancer

4.2.1. Molecular Mechanisms of bEV-Mediated Tumor Promotion and Therapy Resistance

4.2.2. miRNAs and the Lung–Gut Microbiota Axis in Lung Cancer

5. Biomedical Potential of bEVs in Lung Cancer Management

Clinical Trials Investigating Microbiota-Based Therapies in NSCLC

6. Limitations and Challenges

7. Conclusions and New Perspectives

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, R.; Li, J.; Zhou, X. Lung microbiome: New insights into the pathogenesis of respiratory diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natalini, J.G.; Singh, S.; Segal, L.N. The dynamic lung microbiome in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, Z. Gut-lung axis: Role of the gut microbiota in non-small cell lung cancer immunotherapy. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1257515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazumder, M.H.H.; Hussain, S. Air-Pollution-Mediated Microbial Dysbiosis in Health and Disease: Lung-Gut Axis and Beyond. J. Xenobiot. 2024, 14, 1595–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Sun, Y.; Yin, P.; Zuo, S.; Li, H.; Cao, K. Bacterial extracellular vesicles: Emerging mediators of gut-liver axis crosstalk in hepatic diseases. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1620829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.Y.; Seo, J.H.; Choi, J.J.; Ryu, H.J.; Yun, H.; Ha, D.M.; Yang, J. Insight into microbial extracellular vesicles as key communication materials and their clinical implications for lung cancer (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2025, 56, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taverna, S.; Giallombardo, M.; Gil-Bazo, I.; Carreca, A.P.; Castiglia, M.; Chacártegui, J.; Araujo, A.; Alessandro, R.; Pauwels, P.; Peeters, M.; et al. Exosomes isolation and characterization in serum is feasible in non-small cell lung cancer patients: Critical analysis of evidence and potential role in clinical practice. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 28748–28760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, J.A.; Goberdhan, D.C.I.; O’Driscoll, L.; Buzas, E.I.; Blenkiron, C.; Bussolati, B.; Cai, H.; Di Vizio, D.; Driedonks, T.A.P.; Erdbrügger, U.; et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles (MISEV2023): From basic to advanced approaches. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2024, 13, e12404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gristina, V.; Bazan, V.; Barraco, N.; Taverna, S.; Manno, M.; Raccosta, S.; Carreca, A.P.; Bono, M.; Bazan Russo, T.D.; Pepe, F.; et al. On-treatment dynamics of circulating extracellular vesicles in the first-line setting of patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: The LEXOVE prospective study. Mol. Oncol. 2025, 19, 1422–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreca, A.P.; Tinnirello, R.; Miceli, V.; Galvano, A.; Gristina, V.; Incorvaia, L.; Pampalone, M.; Taverna, S.; Iannolo, G. Extracellular Vesicles in Lung Cancer: Implementation in Diagnosis and Therapeutic Perspectives. Cancers 2024, 16, 1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, Z.S.; Dehghan, A.; Halimi, S.; Najafi, F.; Nokhostin, A.; Naeini, A.E.; Akbarzadeh, I.; Ren, Q. Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles: Bridging Pathogen Biology and Therapeutic Innovation. Acta Biomater. 2025, 200, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, D.; Xu, P.; Wang, X.; Du, C.; Zhao, X.; Xu, J. Bacterial extracellular vesicles for gut microbiome-host communication and drug development. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2025, 15, 1816–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, A.; Korani, L.; Yeung, C.L.S.; Tey, S.K.; Yam, J.W.P. The emerging role of bacterial extracellular vesicles in human cancers. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2024, 13, e12521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhanu, P.; Godwin, A.K.; Umar, S.; Mahoney, D.E. Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles in Oncology: Molecular Mechanisms and Future Clinical Applications. Cancers 2025, 17, 1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Pi, Z.; Wang, X.; Shang, C.; Song, C.; Wang, R.; He, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wan, Y.; Mao, W. Microbiome and lung cancer: Carcinogenic mechanisms, early cancer diagnosis, and promising microbial therapies. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2024, 196, 104322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Liu, Y.; Yin, X.; Gong, J.; Li, J. The role of oral microbiota in lung carcinogenesis through the oral-lung axis: A comprehensive review of mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Xiang, Y.; Ren, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Ran, M.; Zhou, W.; Tian, L.; Zheng, X.; Qiao, C.; et al. The tumor microbiome in cancer progression: Mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, L.; Zhou, J.; Xin, Z.; Hauck, J.S.; Na, F.; Tang, J.; Zhou, X.; Lei, Z.; Ying, B. Novel directions of precision oncology: Circulating microbial DNA emerging in cancer-microbiome areas. Precis. Clin. Med. 2022, 5, pbac005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dora, D.; Szőcs, E.; Soós, Á.; Halasy, V.; Somodi, C.; Mihucz, A.; Rostás, M.; Mógor, F.; Lohinai, Z.; Nagy, N. From bench to bedside: An interdisciplinary journey through the gut-lung axis with insights into lung cancer and immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1434804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Bhagchandani, T.; Rai, A.; Nikita, null; Sardarni, U.K.; Bhavesh, N.S.; Gulati, S.; Malik, R.; Tandon, R. Short-Chain Fatty Acid (SCFA) as a Connecting Link between Microbiota and Gut-Lung Axis-A Potential Therapeutic Intervention to Improve Lung Health. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 14648–14671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druszczynska, M.; Sadowska, B.; Kulesza, J.; Gąsienica-Gliwa, N.; Kulesza, E.; Fol, M. The Intriguing Connection Between the Gut and Lung Microbiomes. Pathogens 2024, 13, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-Y.; He, L.-H.; Xu, L.-J.; Li, S.-B. Short-chain fatty acids: Bridges between diet, gut microbiota, and health. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 39, 1728–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bingula, R.; Filaire, M.; Radosevic-Robin, N.; Bey, M.; Berthon, J.-Y.; Bernalier-Donadille, A.; Vasson, M.-P.; Filaire, E. Desired Turbulence? Gut-Lung Axis, Immunity, and Lung Cancer. J. Oncol. 2017, 2017, 5035371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiani, A.K.; Medori, M.C.; Bonetti, G.; Aquilanti, B.; Velluti, V.; Matera, G.; Iaconelli, A.; Stuppia, L.; Connelly, S.T.; Herbst, K.L.; et al. Modern vision of the Mediterranean diet. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2022, 63, E36–E43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belzer, C.; de Vos, W.M. Microbes inside—From diversity to function: The case of Akkermansia. ISME J. 2012, 6, 1449–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xiong, W.; Liang, Z.; Wang, J.; Zeng, Z.; Kołat, D.; Li, X.; Zhou, D.; Xu, X.; Zhao, L. Critical role of the gut microbiota in immune responses and cancer immunotherapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 17, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routy, B.; Le Chatelier, E.; Derosa, L.; Duong, C.P.M.; Alou, M.T.; Daillère, R.; Fluckiger, A.; Messaoudene, M.; Rauber, C.; Roberti, M.P.; et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science 2018, 359, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenda, A.; Iwan, E.; Chmielewska, I.; Krawczyk, P.; Giza, A.; Bomba, A.; Frąk, M.; Rolska, A.; Szczyrek, M.; Kieszko, R.; et al. Presence of Akkermansiaceae in gut microbiome and immunotherapy effectiveness in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. AMB Express 2022, 12, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamrath, L.; Pedersen, T.B.; Møller, M.V.; Volmer, L.M.; Holst-Christensen, L.; Vestermark, L.W.; Donskov, F. Role of the Microbiome and Diet for Response to Cancer Checkpoint Immunotherapy: A Narrative Review of Clinical Trials. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2025, 27, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdova, R.; Kim, J.; Thompson, A.S.; Noh, H.; Shah, S.; Dahm, C.C.; Jensen, C.F.; Mellemkjær, L.; Tjønneland, A.; Katzke, V.; et al. Plant-based dietary patterns and age-specific risk of multimorbidity of cancer and cardiometabolic diseases: A prospective analysis. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2025, 6, 100742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vincenzo, F.; Del Gaudio, A.; Petito, V.; Lopetuso, L.R.; Scaldaferri, F. Gut microbiota, intestinal permeability, and systemic inflammation: A narrative review. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2024, 19, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.M.; Patel, P.H.; Bhogal, R.H.; Harrington, K.J.; Singanayagam, A.; Kumar, S. Altered Microbiome Promotes Pro-Inflammatory Pathways in Oesophago-Gastric Tumourigenesis. Cancers 2024, 16, 3426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derosa, L.; Routy, B.; Thomas, A.M.; Iebba, V.; Zalcman, G.; Friard, S.; Mazieres, J.; Audigier-Valette, C.; Moro-Sibilot, D.; Goldwasser, F.; et al. Intestinal Akkermansia muciniphila predicts clinical response to PD-1 blockade in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yu, Q.; Xiao, J.; Chen, Q.; Fang, M.; Zhao, H. Cigarette Smoke Extract-Treated Mouse Airway Epithelial Cells-Derived Exosomal LncRNA MEG3 Promotes M1 Macrophage Polarization and Pyroptosis in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease by Upregulating TREM-1 via m6A Methylation. Immune Netw. 2024, 24, e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanam, M.; Hossain, C.F.T.Z.; Hyder, T.B.; Tarannum, R.; Oishi, J.F.; Rahman, K.M.M.; Islam, S.B.U.; Bulbul, N.; Sultana Jime, J.; Shishir, M.A.; et al. Bridging two worlds: Host Microbiota crosstalk in health and dysregulation. Innate Immun. 2025, 31, 17534259251392993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Cheng, Y.; Zang, D.; Zhang, M.; Li, X.; Liu, D.; Gao, B.; Zhou, H.; Sun, J.; Han, X.; et al. The Role of Gut Microbiota in Lung Cancer: From Carcinogenesis to Immunotherapy. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 720842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-H.; Wu, Q.-J.; Zhang, T.-N.; Zhao, Y.-H. Gut microbiome and serum short-chain fatty acids are associated with responses to chemo- or targeted therapies in Chinese patients with lung cancer. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1165360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberman, Y.; Kamer, I.; Amir, A.; Goldenberg, S.; Efroni, G.; Daniel-Meshulam, I.; Lobachov, A.; Daher, S.; Hadar, R.; Gantz-Sorotsky, H.; et al. Gut microbial signature in lung cancer patients highlights specific taxa as predictors for durable clinical benefit. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lu, B.; Tang, H.; Jia, X.; Zhou, Q.; Zeng, Y.; Gao, X.; Chen, M.; Xu, Y.; Wang, M.; et al. Gut microbiome metabolites, molecular mimicry, and species-level variation drive long-term efficacy and adverse event outcomes in lung cancer survivors. EBioMedicine 2024, 109, 105427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-Garrido, N.; Badia, J.; Baldomà, L. Microbiota-derived extracellular vesicles in interkingdom communication in the gut. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2021, 10, e12161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Shao, Q.; Ren, Z.; Shang, G.; Han, J.; Cheng, J.; Zheng, Y.; Cheng, F.; Li, C.; Wang, Q.; et al. Mechanisms of pulmonary fibrosis and lung cancer induced by chronic PM2.5 exposure: Focus on the airway epithelial barrier and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 297, 118253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thapa, R.; Magar, A.T.; Shrestha, J.; Panth, N.; Idrees, S.; Sadaf, T.; Bashyal, S.; Elwakil, B.H.; Sugandhi, V.V.; Rojekar, S.; et al. Influence of gut and lung dysbiosis on lung cancer progression and their modulation as promising therapeutic targets: A comprehensive review. MedComm 2024, 5, e70018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, M.; Wang, F.; Bao, M.; Zhu, L. Environmental risk factors, protective factors and lifestyles for lung cancer: An umbrella review. Front. Public. Health 2025, 13, 1623840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, M.H.H.; Gandhi, J.; Majumder, N.; Wang, L.; Cumming, R.I.; Stradtman, S.; Velayutham, M.; Hathaway, Q.A.; Shannahan, J.; Hu, G.; et al. Lung-gut axis of microbiome alterations following co-exposure to ultrafine carbon black and ozone. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2023, 20, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pat, Y.; Yazici, D.; D’Avino, P.; Li, M.; Ardicli, S.; Ardicli, O.; Mitamura, Y.; Akdis, M.; Dhir, R.; Nadeau, K.; et al. Recent advances in the epithelial barrier theory. Int. Immunol. 2024, 36, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kayalar, Ö.; Rajabi, H.; Konyalilar, N.; Mortazavi, D.; Aksoy, G.T.; Wang, J.; Bayram, H. Impact of particulate air pollution on airway injury and epithelial plasticity; underlying mechanisms. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1324552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaluç, N.; Bertorello, S.; Tombul, O.K.; Baldi, S.; Nannini, G.; Bartolucci, G.; Niccolai, E.; Amedei, A. Gut-lung microbiota dynamics in mice exposed to Nanoplastics. NanoImpact 2024, 36, 100531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neurath, M.F.; Artis, D.; Becker, C. The intestinal barrier: A pivotal role in health, inflammation, and cancer. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, 10, 573–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albano, G.D.; Montalbano, A.M.; Gagliardo, R.; Anzalone, G.; Profita, M. Impact of Air Pollution in Airway Diseases: Role of the Epithelial Cells (Cell Models and Biomarkers). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albano, G.D.; Longo, V.; Montalbano, A.M.; Aloi, N.; Barone, R.; Cibella, F.; Profita, M.; Colombo, P. Extracellular vesicles from PBDE-47 treated M(LPS) THP-1 macrophages modulate the expression of markers of epithelial integrity, EMT, inflammation and muco-secretion in ALI culture of airway epithelium. Life Sci. 2023, 322, 121616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glencross, D.A.; Ho, T.-R.; Camiña, N.; Hawrylowicz, C.M.; Pfeffer, P.E. Air pollution and its effects on the immune system. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 151, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadokoro, T.; Wang, Y.; Barak, L.S.; Bai, Y.; Randell, S.H.; Hogan, B.L.M. IL-6/STAT3 promotes regeneration of airway ciliated cells from basal stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, E3641–E3649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-C.; Lu, Y.-H.; Huang, Y.-L.; Huang, S.L.; Chuang, H.-C. Air Pollution Effects to the Subtype and Severity of Lung Cancers. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 835026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharibvand, L.; Lawrence Beeson, W.; Shavlik, D.; Knutsen, R.; Ghamsary, M.; Soret, S.; Knutsen, S.F. The association between ambient fine particulate matter and incident adenocarcinoma subtype of lung cancer. Environ. Health 2017, 16, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, J.A.; Liao, L.M.; Graubard, B.I.; Kaufman, J.D.; Silverman, D.T.; Jones, R.R. Ambient air pollution exposure and lung cancer risk in a large prospective U.S. cohort. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 1002, 180490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, T.-Y.; Chang, C.-C.; Luo, C.-S.; Chen, K.-Y.; Yeh, Y.-K.; Zheng, J.-Q.; Wu, S.-M. Targeting Lung-Gut Axis for Regulating Pollution Particle-Mediated Inflammation and Metabolic Disorders. Cells 2023, 12, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortés, M.; Olate, P.; Rodriguez, R.; Diaz, R.; Martínez, A.; Hernández, G.; Sepulveda, N.; Paz, E.A.; Quiñones, J. Human Microbiome as an Immunoregulatory Axis: Mechanisms, Dysbiosis, and Therapeutic Modulation. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Cai, Y.; Garssen, J.; Henricks, P.A.J.; Folkerts, G.; Braber, S. The Bidirectional Gut-Lung Axis in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 207, 1145–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, S.; Mande, S.S. Diet, Microbiota and Gut-Lung Connection. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Zuo, T.; Frey, N.; Rangrez, A.Y. A systematic framework for understanding the microbiome in human health and disease: From basic principles to clinical translation. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlon, M.A.; Bird, A.R. The impact of diet and lifestyle on gut microbiota and human health. Nutrients 2014, 7, 17–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bella, M.A.; Taverna, S. Extracellular Vesicles: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Applications in Cancer. Biology 2024, 13, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammarata, G.; de Miguel-Perez, D.; Russo, A.; Peleg, A.; Dolo, V.; Rolfo, C.; Taverna, S. Emerging noncoding RNAs contained in extracellular vesicles: Rising stars as biomarkers in lung cancer liquid biopsy. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2022, 14, 17588359221131229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammarata, G.; Masucci, A.; Giusti, I.; Dolo, V.; Di Sano, C.; Taverna, S.; Pace, E. Effects of small extracellular vesicles isolated from pleural effusion on lung cancer cell proliferation and migration. Hum. Cell 2025, 39, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretto, E.; Urpì-Ferreruela, M.; Casanova, G.R.; González-Suárez, B. The Role of Gut Microbiota in Gastrointestinal Immune Homeostasis and Inflammation: Implications for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y. Advances in intestinal epithelium and gut microbiota interaction. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1499202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Kan, J.; Fu, C.; Liu, X.; Cui, Z.; Wang, S.; Le, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Insights into the unique roles of extracellular vesicles for gut health modulation: Mechanisms, challenges, and perspectives. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2024, 7, 100301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Wang, X.; Guo, Y.; Yan, J.; Abuduwaili, A.; Aximujiang, K.; Yan, J.; Wu, M. Gut microbiota influence tumor development and Alter interactions with the human immune system. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 40, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Miguel-Perez, D.; Russo, A.; Arrieta, O.; Ak, M.; Barron, F.; Gunasekaran, M.; Mamindla, P.; Lara-Mejia, L.; Peterson, C.B.; Er, M.E.; et al. Extracellular vesicle PD-L1 dynamics predict durable response to immune-checkpoint inhibitors and survival in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 41, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Miguel-Perez, D.; Russo, A.; Gunasekaran, M.; Buemi, F.; Hester, L.; Fan, X.; Carter-Cooper, B.A.; Lapidus, R.G.; Peleg, A.; Arroyo-Hernández, M.; et al. Baseline extracellular vesicle TGF-β is a predictive biomarker for response to immune checkpoint inhibitors and survival in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer 2023, 129, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Cong, Y. Gut microbiota-derived metabolites in the regulation of host immune responses and immune-related inflammatory diseases. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2021, 18, 866–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.D.; Akbar, R.; Oliverio, A.; Thapa, K.; Wang, X.; Fan, G.-C. Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles in the Regulation of Inflammatory Response and Host-Microbe Interactions. Shock 2024, 61, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghamajidi, A.; Maleki Vareki, S. The Effect of the Gut Microbiota on Systemic and Anti-Tumor Immunity and Response to Systemic Therapy against Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 3563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Zhu, X.; Wang, Y.; Lu, S. The gut microbiota improves the efficacy of immune-checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy against tumors: From association to cause and effect. Cancer Lett. 2024, 598, 217123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lin, S.; Wang, L.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, R.; Liu, J. Versatility of bacterial outer membrane vesicles in regulating intestinal homeostasis. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eade5079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Chen, P.; Xi, Y.; Sheng, J. From trash to treasure: The role of bacterial extracellular vesicles in gut health and disease. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1274295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Liu, M.; Jiang, L.; Chen, Z.; Tian, W.; Li, K.; Yu, B.; Zhang, W.; Li, S.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles: Emerging Regulators in the Gut-Organ Axis and Prospective Biomedical Applications. Curr. Microbiol. 2025, 82, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Młynarczyk, M.; Gajdowska, F.; Matinha-Cardoso, J.; Oliveira, P.; Tamagnini, P.; Belka, M.; Mantej, J.; Gutowska-Owsiak, D.; Hewelt-Belka, W. Evaluating Novel Direct Injection Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Method and Extraction-Based Workflows for Untargeted Lipidomics of Extracellular Vesicles. J. Proteome Res. 2025, 24, 5412–5426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leggio, L.; Paternò, G.; Vivarelli, S.; Bonasera, A.; Pignataro, B.; Iraci, N.; Arrabito, G. Label-free approaches for extracellular vesicle detection. iScience 2023, 26, 108105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Lersner, A.K.; Fernandes, F.; Ozawa, P.M.M.; Jackson, M.; Masureel, M.; Ho, H.; Lima, S.M.; Vagner, T.; Sung, B.H.; Wehbe, M.; et al. Multiparametric Single-Vesicle Flow Cytometry Resolves Extracellular Vesicle Heterogeneity and Reveals Selective Regulation of Biogenesis and Cargo Distribution. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 10464–10484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMillan, H.M.; Kuehn, M.J. The extracellular vesicle generation paradox: A bacterial point of view. EMBO J. 2021, 40, e108174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, S.; Weng, W.; Jing, Y.; Su, J. Bacterial extracellular vesicles as bioactive nanocarriers for drug delivery: Advances and perspectives. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 14, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulkens, J.; De Wever, O.; Hendrix, A. Analyzing bacterial extracellular vesicles in human body fluids by orthogonal biophysical separation and biochemical characterization. Nat. Protoc. 2020, 15, 40–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malesza, I.J.; Malesza, M.; Walkowiak, J.; Mussin, N.; Walkowiak, D.; Aringazina, R.; Bartkowiak-Wieczorek, J.; Mądry, E. High-Fat, Western-Style Diet, Systemic Inflammation, and Gut Microbiota: A Narrative Review. Cells 2021, 10, 3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Garrido, N.; Badia, J.; Baldomà, L. Modulation of Dendritic Cells by Microbiota Extracellular Vesicles Influences the Cytokine Profile and Exosome Cargo. Nutrients 2022, 14, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budden, K.F.; Gellatly, S.L.; Wood, D.L.A.; Cooper, M.A.; Morrison, M.; Hugenholtz, P.; Hansbro, P.M. Emerging pathogenic links between microbiota and the gut-lung axis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.-S.; Choi, E.-J.; Lee, W.-H.; Choi, S.-J.; Roh, T.-Y.; Park, J.; Jee, Y.-K.; Zhu, Z.; Koh, Y.-Y.; Gho, Y.S.; et al. Extracellular vesicles, especially derived from Gram-negative bacteria, in indoor dust induce neutrophilic pulmonary inflammation associated with both Th1 and Th17 cell responses. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2013, 43, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Choi, J.P.; Kim, M.H.; Park, H.K.; Yang, S.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, T.B.; Cho, Y.S.; Oh, Y.M.; Jee, Y.K.; et al. IgG Sensitization to Extracellular Vesicles in Indoor Dust Is Closely Associated With the Prevalence of Non-Eosinophilic Asthma, COPD, and Lung Cancer. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2016, 8, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preet, R.; Islam, M.A.; Shim, J.; Rajendran, G.; Mitra, A.; Vishwakarma, V.; Kutz, C.; Choudhury, S.; Pathak, H.; Dai, Q.; et al. Gut commensal Bifidobacterium-derived extracellular vesicles modulate the therapeutic effects of anti-PD-1 in lung cancer. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Kim, E.K.; Park, H.J.; McDowell, A.; Kim, Y.-K. The impact of bacteria-derived ultrafine dust particles on pulmonary diseases. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessle, C.; Andersson, B.; Wold, A.E. Gram-positive bacteria are potent inducers of monocytic interleukin-12 (IL-12) while gram-negative bacteria preferentially stimulate IL-10 production. Infect. Immun. 2000, 68, 3581–3586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, R.; Thornton, C.S.; Johnston, B.; Lee, A.H.Y.; Cheng, Z. Pseudomonas aeruginosa in chronic lung disease: Untangling the dysregulated host immune response. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1405376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.; Xu, X.-L.; Duan, Y.-F.; Long, L.; Chen, J.-Y.; Yin, Y.-H.; Zhu, Y.-G.; Huang, Q. Extracellular Vesicles Are Prevalent and Effective Carriers of Environmental Allergens in Indoor Dust. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 1969–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, I.; Pathak, A.; Bayik, D.; Watson, D.C. Harnessing Bacterial Extracellular Vesicle Immune Effects for Cancer Therapy. Pathog. Immun. 2024, 9, 56–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meganathan, V.; Moyana, R.; Natarajan, K.; Kujur, W.; Kusampudi, S.; Mulik, S.; Boggaram, V. Bacterial extracellular vesicles isolated from organic dust induce neutrophilic inflammation in the lung. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2020, 319, L893–L907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Yang, C.; Liu, L.; Mai, G.; Li, H.; Wu, L.; Jin, M.; Chen, Y. Commensal bacteria-derived extracellular vesicles suppress ulcerative colitis through regulating the macrophages polarization and remodeling the gut microbiota. Microb. Cell Fact. 2022, 21, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melo-Marques, I.; Cardoso, S.M.; Empadinhas, N. Bacterial extracellular vesicles at the interface of gut microbiota and immunity. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2396494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, L.; Liu, B.; Wang, Y.; Tang, B.; Xu, T.; Fu, J.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Ge, L.; Wei, H.; et al. Intestinal Lactobacillus murinus-derived small RNAs target porcine polyamine metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2413241121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoji, F.; Yamaguchi, M.; Okamoto, M.; Takamori, S.; Yamazaki, K.; Okamoto, T.; Maehara, Y. Gut microbiota diversity and specific composition during immunotherapy in responders with non-small cell lung cancer. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 1040424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Song, S.; Liu, J.; Chen, F.; Li, X.; Wu, G. Gut microbiota as a new target for anticancer therapy: From mechanism to means of regulation. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2025, 11, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, B.; Huang, J. Influences of bacterial extracellular vesicles on macrophage immune functions. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1411196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; E, Q.; Naveed, M.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, M. The biological activity and potential of probiotics-derived extracellular vesicles as postbiotics in modulating microbiota-host communication. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2025, 23, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.-W.; Xia, K.; Liu, Y.-W.; Liu, J.-H.; Rao, S.-S.; Hu, X.-K.; Chen, C.-Y.; Xu, R.; Wang, Z.-X.; Xie, H. Extracellular Vesicles from Akkermansia muciniphila Elicit Antitumor Immunity Against Prostate Cancer via Modulation of CD8+ T Cells and Macrophages. Int. J. Nanomed. 2021, 16, 2949–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nucera, F.; Ruggeri, P.; Spagnolo, C.C.; Santarpia, M.; Ieni, A.; Monaco, F.; Tuccari, G.; Pioggia, G.; Gangemi, S. MiRNAs and Microbiota in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC): Implications in Pathogenesis and Potential Role in Predicting Response to ICI Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, R.; Zhang, D.; Qi, S.; Liu, Y. Metabolite interactions between host and microbiota during health and disease: Which feeds the other? Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 160, 114295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yue, H.; Wang, S.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Guo, P.; Ma, G.; Wei, W. Advances of bacteria-based delivery systems for modulating tumor microenvironment. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2022, 188, 114444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, S.; Tennekoon, K.H.; Karunanayake, E.H. Interaction of Gut Microbiome and Host microRNAs with the Occurrence of Colorectal and Breast Cancer and Their Impact on Patient Immunity. Onco Targets Ther. 2021, 14, 5115–5129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Nogales, A.; Algieri, F.; Garrido-Mesa, J.; Vezza, T.; Utrilla, M.P.; Chueca, N.; Garcia, F.; Olivares, M.; Rodríguez-Cabezas, M.E.; Gálvez, J. Differential intestinal anti-inflammatory effects of Lactobacillus fermentum and Lactobacillus salivarius in DSS mouse colitis: Impact on microRNAs expression and microbiota composition. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1700144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Zhang, P.-J.; Li, C.-H.; Lv, Z.-M.; Zhang, W.-W.; Jin, C.-H. miRNA-133 augments coelomocyte phagocytosis in bacteria-challenged Apostichopus japonicus via targeting the TLR component of IRAK-1 in vitro and in vivo. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, B.A. Extracellular Vesicles and Host-Pathogen Interactions: A Review of Inter-Kingdom Signaling by Small Noncoding RNA. Genes 2021, 12, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, F.; Boedicker, J.Q. Genetic cargo and bacterial species set the rate of vesicle-mediated horizontal gene transfer. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanaei, M.-J.; Razi, S.; Pourbagheri-Sigaroodi, A.; Bashash, D. The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in lung cancer; oncogenic alterations, therapeutic opportunities, challenges, and a glance at the application of nanoparticles. Transl. Oncol. 2022, 18, 101364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuerban, K.; Gao, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, J.; Dong, M.; Wu, L.; Ye, R.; Feng, M.; Ye, L. Doxorubicin-loaded bacterial outer-membrane vesicles exert enhanced anti-tumor efficacy in non-small-cell lung cancer. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2020, 10, 1534–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X. The paradoxical role of IFN-γ in cancer: Balancing immune activation and immune evasion. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2025, 272, 156046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurunathan, S.; Ajmani, A.; Kim, J.-H. Extracellular nanovesicles produced by Bacillus licheniformis: A potential anticancer agent for breast and lung cancer. Microb. Pathog. 2023, 185, 106396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Q.; Yin, Y.; Geng, Y.; Xu, L.; Liang, S.; Xiang, J.; Fan, J.; Tang, J.; et al. A plug-and-play monofunctional platform for targeted degradation of extracellular proteins and vesicles. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Shu, C.; Hua, L.; Zhao, Y.; Xie, H.; Qi, J.; Gao, F.; Gao, R.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Modified bacterial outer membrane vesicles induce autoantibodies for tumor therapy. Acta Biomater. 2020, 108, 300–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Deng, D.; Li, S.; Ren, J.; Huang, W.; Liu, D.; Wang, W. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid assessment facilitates precision medicine for lung cancer. Cancer Biol. Med. 2023, 21, 230–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Li, Y.; Yin, X.; Fan, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Bai, G.; Li, K.; Shi, Y.; et al. Utilizing Engineered Bacteria as “Cell Factories” In Vivo for Intracellular RNA-Loaded Outer Membrane Vesicles’ Self-Assembly in Tumor Treatment. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 35296–35309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, W.; Zhou, K.; Lei, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhu, H. Gut microbiota shapes cancer immunotherapy responses. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2025, 11, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tegegne, B.A.; Abebaw, D.; Teffera, Z.H.; Fenta, A.; Belew, H.; Belayneh, M.; Jemal, M.; Getinet, M.; Baylie, T.; Tamene, F.B.; et al. Microbial Therapeutics in Cancer: Translating Probiotics, Prebiotics, Synbiotics, and Postbiotics From Mechanistic Insights to Clinical Applications: A Topical Review. FASEB J. 2025, 39, e71146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Li, W.; Li, Z.; Wu, Q.; Sun, S. Influence of Microbiota on Tumor Immunotherapy. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2024, 20, 2264–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiousi, D.E.; Kouroutzidou, A.Z.; Neanidis, K.; Karavanis, E.; Matthaios, D.; Pappa, A.; Galanis, A. The Role of the Gut Microbiome in Cancer Immunotherapy: Current Knowledge and Future Directions. Cancers 2023, 15, 2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Tian, J. Hotspots and frontiers of extracellular vesicles and lung cancer: A bibliometric and visualization analysis from 2002 to 2024. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauth, S.; Karmakar, S.; Batra, S.K.; Ponnusamy, M.P. Recent advances in organoid development and applications in disease modeling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2021, 1875, 188527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uemura, T.; Kawashima, A.; Jingushi, K.; Motooka, D.; Saito, T.; Nesrine, S.; Oka, T.; Okuda, Y.; Yamamoto, A.; Yamamichi, G.; et al. Bacteria-derived DNA in serum extracellular vesicles are biomarkers for renal cell carcinoma. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.-Y.; Kang, C.-S.; Seo, H.-C.; Shin, J.-C.; Kym, S.-M.; Park, Y.-S.; Shin, T.-S.; Kim, J.-G.; Kim, Y.-K. Bacteria-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Urine as a Novel Biomarker for Gastric Cancer: Integration of Liquid Biopsy and Metagenome Analysis. Cancers 2021, 13, 4687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujikawa, K.; Saito, T.; Kawashima, A.; Jingushi, K.; Motooka, D.; Nakai, S.; Hagi, T.; Momose, K.; Yamashita, K.; Tanaka, K.; et al. Bacteria-derived DNA in serum extracellular vesicles as a biomarker for gastric cancer. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2025, 74, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Bacterial Species | bEV Cargo | Experimental Model | Mechanism/Pathway Activated | Effect on Lung Cancer | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | LPS miR-21 miR-155 | Lung epithelial cells | TLR2/4 → NF-κB, PI3K/AKT | Inflammation immune evasion chemoresistance | [93] |

| Helicobacter pylori | miR-155 | GC | Downregulation of Bax | Apoptosis resistance | [79] |

| Bifidobacterium spp. | PD-L1-inducing components | NSCLC | TLR4 → NF-κB → PD-L1 upregulation | Modulation of response to anti-PD-1 therapy | [26] |

| Akkermansia muciniphila | PD-1 | NSCLC | PD-1 blockade | [87] | |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum | miR-21 | CRC | PTEN suppression → cell proliferation | Tumor growth promotion | [65] |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae (attenuated) | DOX-loaded bEVs | NSCLC | Intracellular drug delivery | Cytotoxicity in NSCLC cells | [113] |

| Bacillus licheniformis | Native bEV proteins | liver, stomach pancreas cancer | ↑ p53, ↑ p21, ↑ caspase-3/9, ↓ Bcl-2 | Induction of apoptosis, inhibition of proliferation | [94] |

| Trial ID | Intervention/Therapy | Key Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| NCT04951583 | FMT + ICI | Patients with metastatic NSCLC (and melanoma) receiving ICI + FMT. Objective: evaluate the combined antitumor activity |

| NCT05008861 | Encapsulated FMT combined with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy | Patients with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC after first-line PD-1/PD-L1 therapy. Assessing safety and impact on the gut microbiota composition |

| NCT04699721 | Neoadjuvant chemo-immunotherapy + probiotics in resectable NSCLC | Evaluates safety and efficacy of probiotic supplementation in patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemo-immunotherapy for resectable NSCLC. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Albano, G.D.; Taverna, S. From Microbiota to Cancer: Role of Extracellular Vesicles in Gut–Lung Axis. Cancers 2025, 17, 3946. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243946

Albano GD, Taverna S. From Microbiota to Cancer: Role of Extracellular Vesicles in Gut–Lung Axis. Cancers. 2025; 17(24):3946. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243946

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlbano, Giusy Daniela, and Simona Taverna. 2025. "From Microbiota to Cancer: Role of Extracellular Vesicles in Gut–Lung Axis" Cancers 17, no. 24: 3946. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243946

APA StyleAlbano, G. D., & Taverna, S. (2025). From Microbiota to Cancer: Role of Extracellular Vesicles in Gut–Lung Axis. Cancers, 17(24), 3946. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243946