Adding Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy to Chemotherapy in Non-Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: A Propensity-Matched Cohort Study from a Tertiary Cancer Center

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

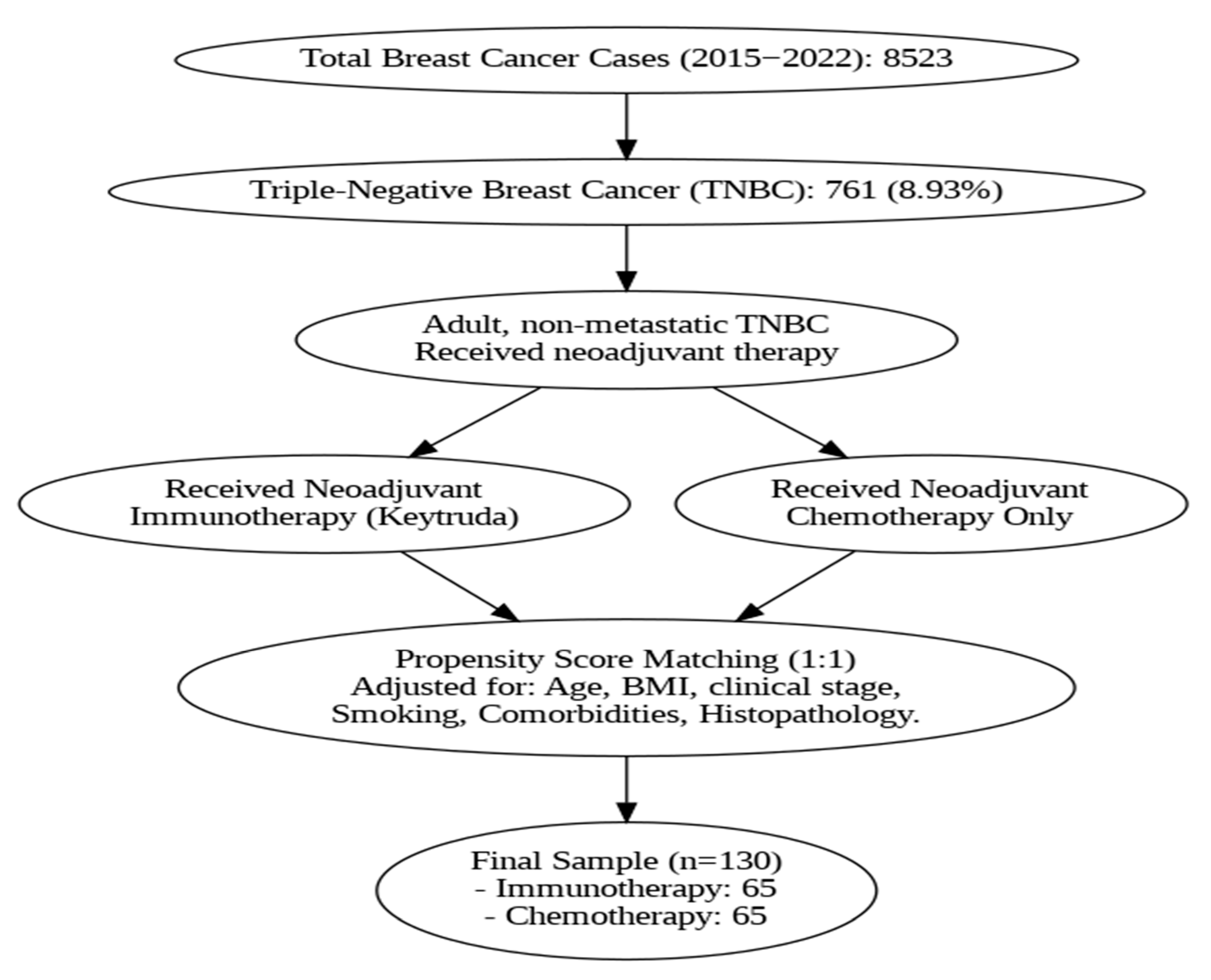

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Population

2.2. Treatment Protocols

2.3. Outcomes Definition

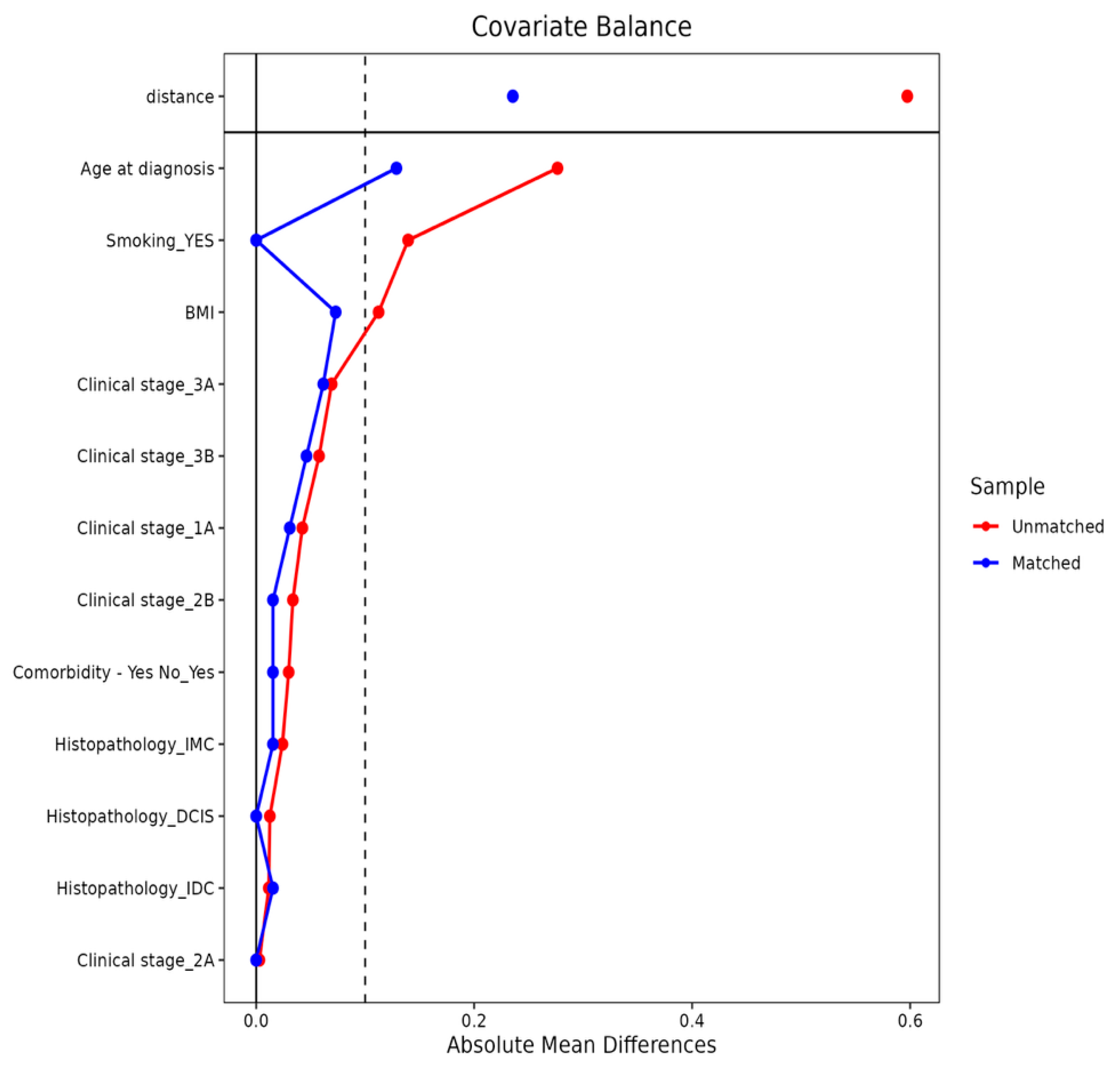

2.4. Propensity Score Matching and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics Before and After Matching

3.2. Immunotherapy Induced Adverse Events

3.3. Postoperative Complications Among the Study Groups

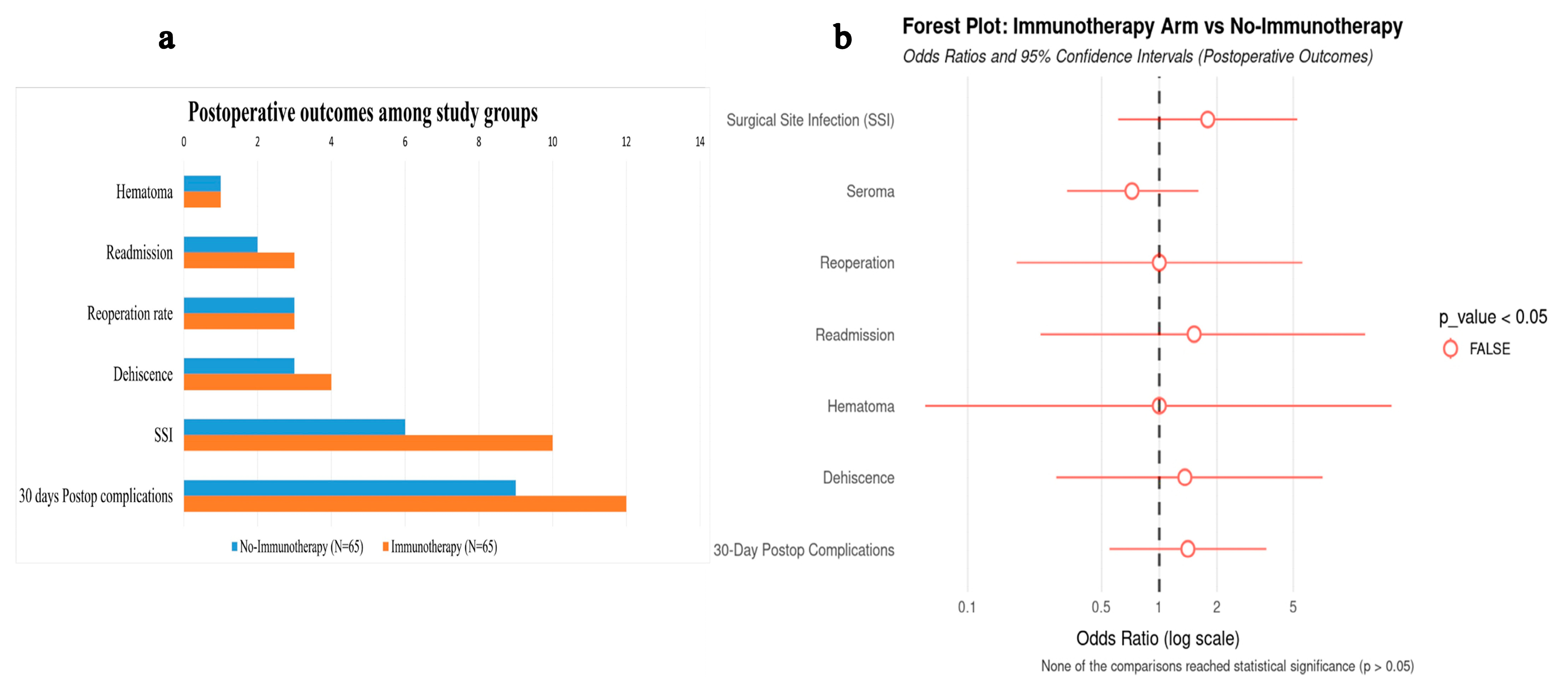

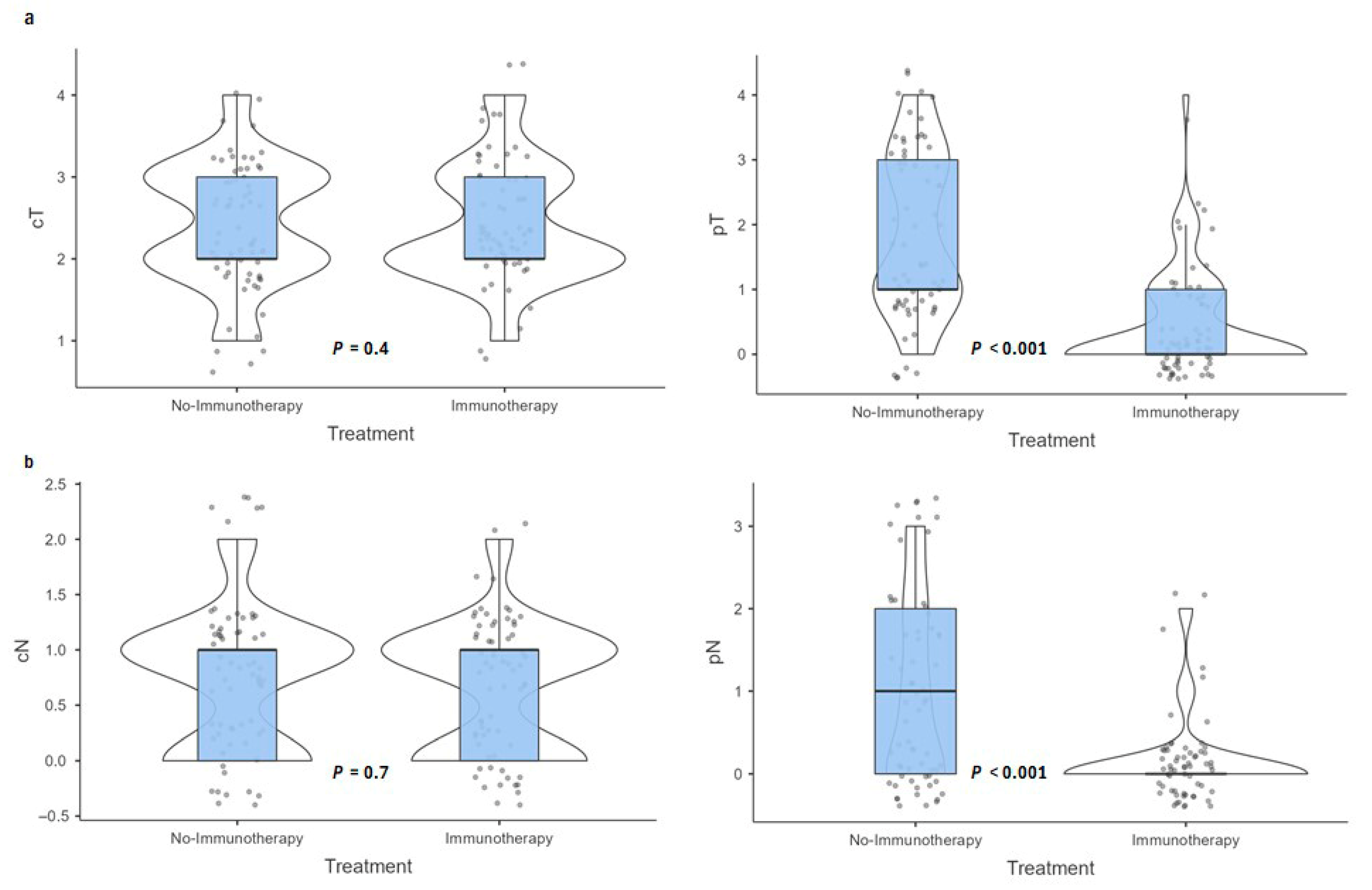

3.4. Pathological Outcomes

3.5. Adjuvant Therapy Patterns

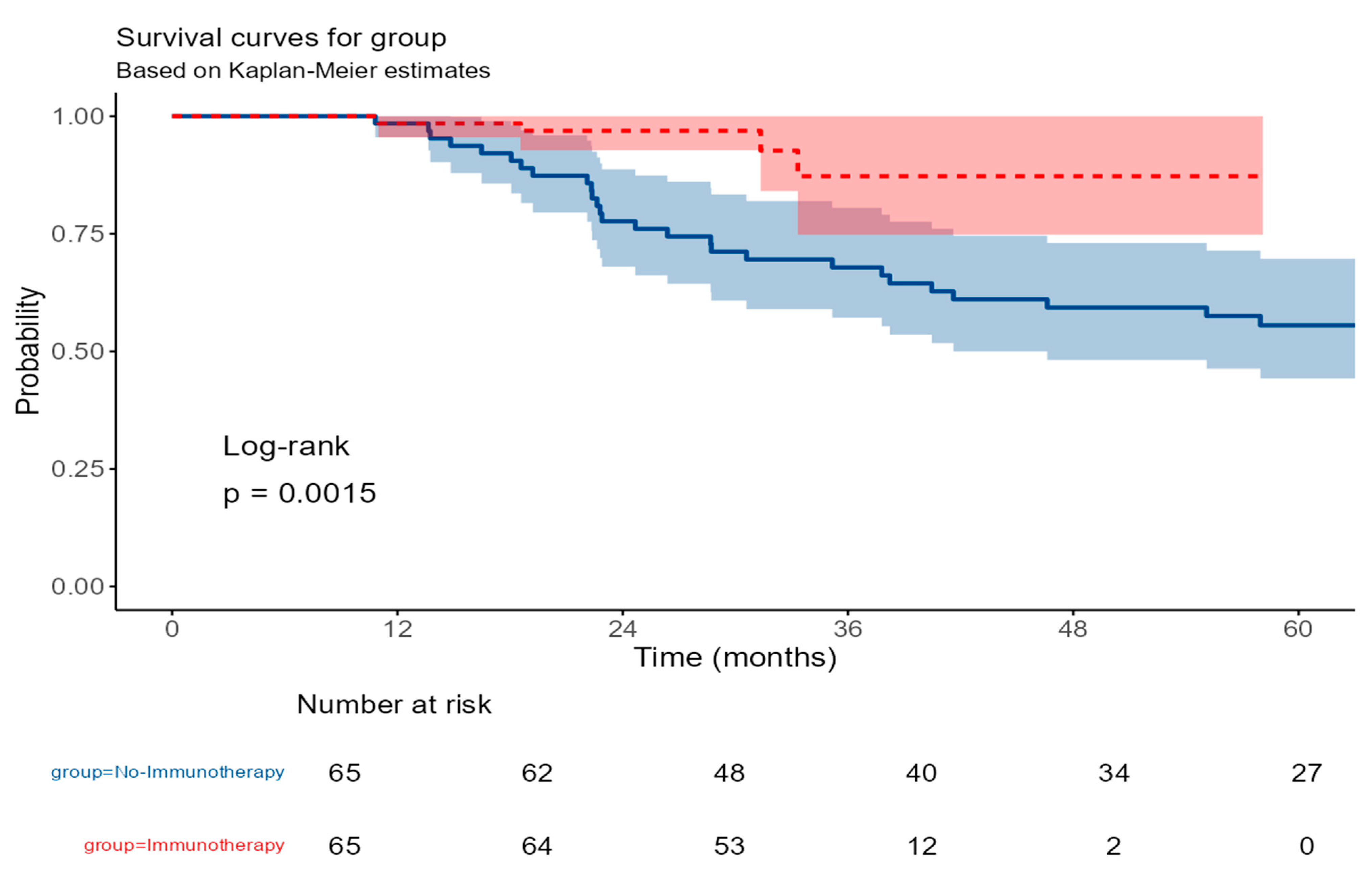

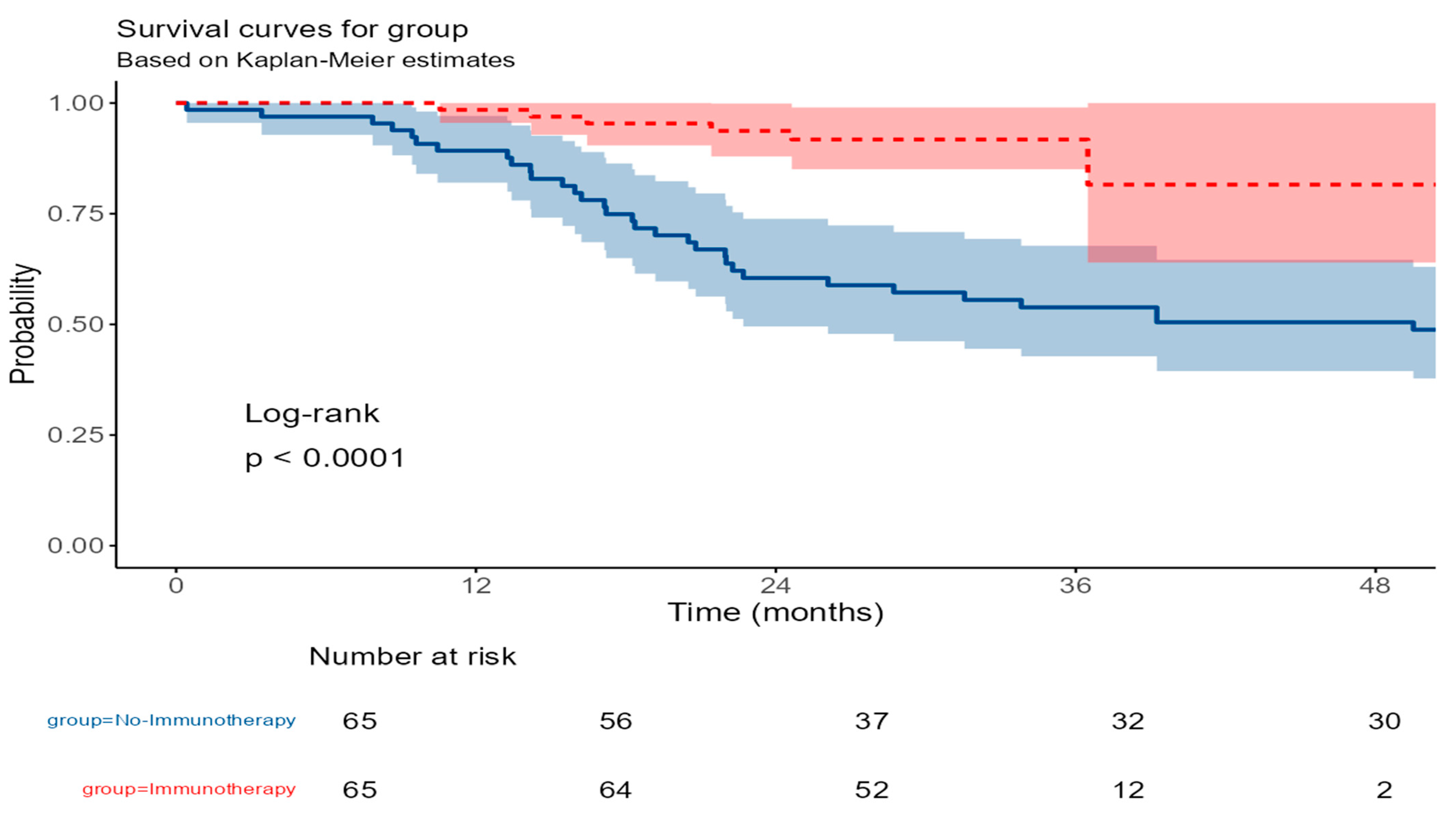

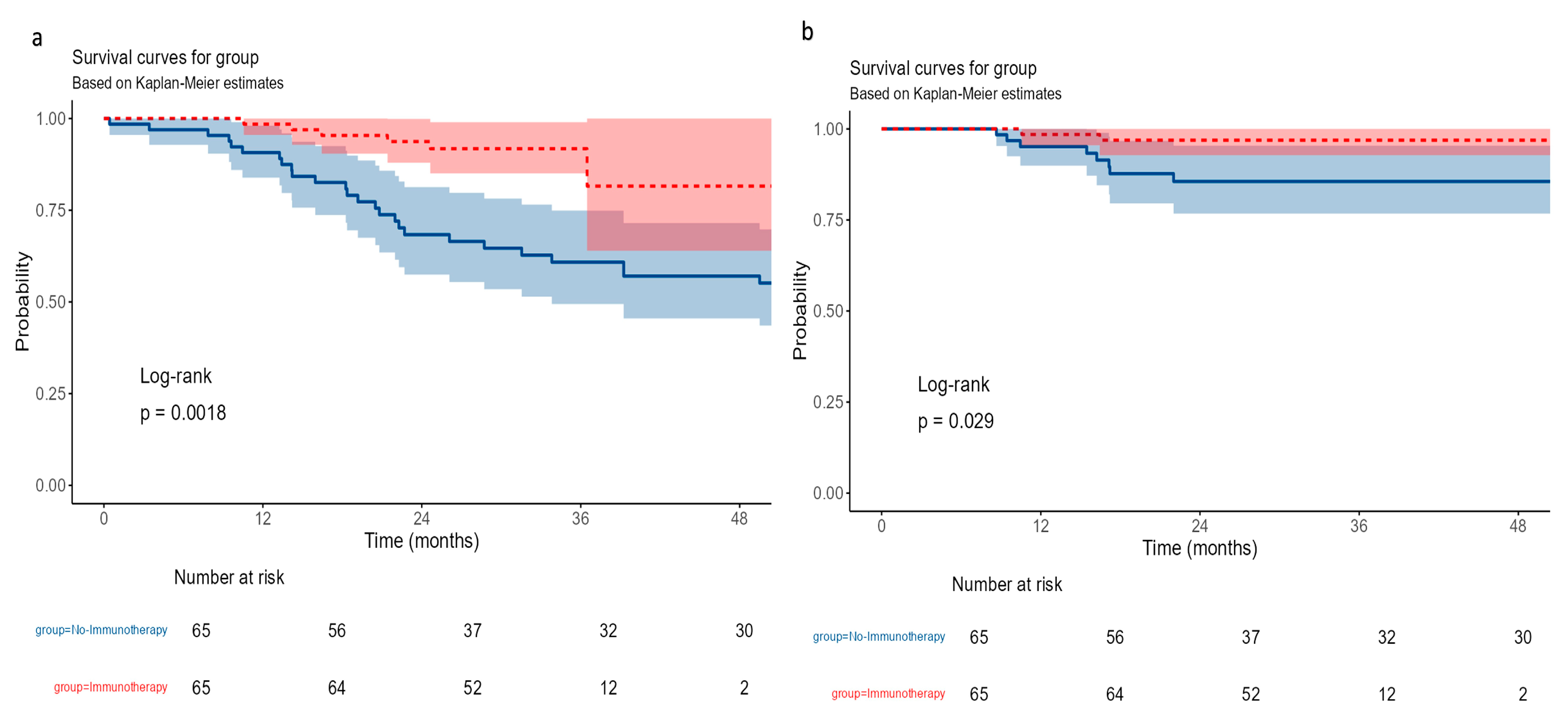

- Survival outcomes—Overall survival outcomes

3.6. Recurrence-Free Survival (RFS)

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AC | Doxorubicin and Cyclophosphamide |

| AD | Axillary Dissection |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| DCIS | Ductal Carcinoma in Situ |

| DRFS | Distant Recurrence-Free Survival |

| EFS | Event-Free Survival |

| ER | Estrogen Receptors |

| HER2 | Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 |

| ICIs | Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors |

| IDC | Invasive Ductal Carcinoma |

| ILC | Invasive Lobular Carcinoma |

| IMC | Invasive Mammary Carcinoma |

| iRAEs | Immune-Related Adverse Events |

| KHCC | King Hussein Cancer Center |

| LN | Lymph Node |

| LRFS | Locoregional Recurrence-Free Survival |

| NACi | Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy with Immunotherapy |

| NACT | Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| OS | Overall Survival |

| pCR | Pathological Complete Response |

| PD-L1 | Programmed Death-Ligand 1 |

| PR | Progesterone Receptors |

| PSM | Propensity Score Matching |

| RFS | Recurrence-Free Survival |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SMDs | Standardized Mean Differences |

| SSI | Surgical Site Infection |

| TMB | Tumor Mutational Burden |

| TNBC | Triple-Negative Breast Cancer |

Appendix A

References

- Dogra, A.K.; Prakash, A.; Gupta, S.; Gupta, M. Prognostic Significance and Molecular Classification of Triple Negative Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Breast Health 2025, 21, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.K.; Childs, B.H.; Pegram, M. Triple Negative Breast Cancer: Unmet Medical Needs. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2011, 125, 627–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-Q.; Russo, J. ERalpha-Negative and Triple Negative Breast Cancer: Molecular Features and Potential Therapeutic Approaches. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1796, 162–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, A.M.; Eun Kwon, J.; Ali, T.; Jang, J.; Ullah, I.; Lee, Y.-G.; Park, D.W.; Park, J.; Jeang, J.W.; Kang, S.C. Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Epidemiology, Molecular Mechanisms, and Modern Vaccine-Based Treatment Strategies. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2023, 212, 115545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, N.; Wu, H.; Yu, Z. Advancements and Challenges in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: A Comprehensive Review of Therapeutic and Diagnostic Strategies. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1405491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.S.; Yost, S.E.; Yuan, Y. Neoadjuvant Treatment for Triple Negative Breast Cancer: Recent Progresses and Challenges. Cancers 2020, 12, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diana, A.; Carlino, F.; Franzese, E.; Oikonomidou, O.; Criscitiello, C.; De Vita, F.; Ciardiello, F.; Orditura, M. Early Triple Negative Breast Cancer: Conventional Treatment and Emerging Therapeutic Landscapes. Cancers 2020, 12, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortazar, P.; Zhang, L.; Untch, M.; Mehta, K.; Costantino, J.P.; Wolmark, N.; Bonnefoi, H.; Cameron, D.; Gianni, L.; Valagussa, P.; et al. Pathological Complete Response and Long-Term Clinical Benefit in Breast Cancer: The CTNeoBC Pooled Analysis. Lancet 2014, 384, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spring, L.M.; Fell, G.; Arfe, A.; Sharma, C.; Greenup, R.; Reynolds, K.L.; Smith, B.L.; Alexander, B.; Moy, B.; Isakoff, S.J.; et al. Pathologic Complete Response after Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy and Impact on Breast Cancer Recurrence and Survival: A Comprehensive Meta-Analysis. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 2838–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toss, A.; Venturelli, M.; Civallero, M.; Piombino, C.; Domati, F.; Ficarra, G.; Combi, F.; Cabitza, E.; Caggia, F.; Barbieri, E.; et al. Predictive Factors for Relapse in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Patients without Pathological Complete Response after Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1016295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuhadra, N.; Stecklein, S.; Sharma, P.; Moulder, S. Early-Stage Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Time to Optimize Personalized Strategies. Oncologist 2022, 27, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obidiro, O.; Battogtokh, G.; Akala, E.O. Triple Negative Breast Cancer Treatment Options and Limitations: Future Outlook. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loizides, S.; Constantinidou, A. Triple Negative Breast Cancer: Immunogenicity, Tumor Microenvironment, and Immunotherapy. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 1095839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabit, H.; Adel, A.; Abdelfattah, M.M.; Ramadan, R.M.; Nazih, M.; Abdel-Ghany, S.; El-Hashash, A.; Arneth, B. The Role of Tumor Microenvironment and Immune Cell Crosstalk in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC): Emerging Therapeutic Opportunities. Cancer Lett. 2025, 628, 217865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.; Cortés, J.; Dent, R.; Pusztai, L.; McArthur, H.; Kümmel, S.; Denkert, C.; Park, Y.H.; Im, S.-A.; Ahn, J.-H.; et al. Pembrolizumab Plus Chemotherapy Followed by Pembrolizumab in Patients With Early Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2342107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, P.; Cortés, J.; Dent, R.; Pusztai, L.; McArthur, H.L.; Kuemmel, S.; Bergh, J.; Denkert, C.; Park, Y.H.; Hui, R.; et al. KEYNOTE-522: Phase III Study of Pembrolizumab (Pembro) + Chemotherapy (Chemo) vs. Placebo (Pbo) + Chemo as Neoadjuvant Treatment, Followed by Pembro vs Pbo as Adjuvant Treatment for Early Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC). Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, v853–v854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, T.-Y.; Bi, Z. Exploration of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Neoadjuvant Therapy of Early-Stage Breast Cancer. Int. J. Surg. 2024, 110, 2479–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, P.; Cortés, J.; Dent, R.A.; McArthur, H.L.; Pusztai, L.; Kummel, S.; Denkert, C.; Park, Y.H.; Hui, R.; Harbeck, N.; et al. LBA4 Neoadjuvant Pembrolizumab or Placebo plus Chemotherapy Followed by Adjuvant Pembrolizumab or Placebo for High-Risk Early-Stage TNBC: Overall Survival Results from the Phase III KEYNOTE-522 Study. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, S1204–S1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, R.; Chen, X.; Yang, J.; Xu, B. Immunotherapy in Breast Cancer: Current Landscape and Emerging Trends. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2025, 14, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Current Treatment Landscape for Early Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC). J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mezzanotte-Sharpe, J.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Choi, D.; Sheffield, H.; Zelinskas, S.; Proskuriakova, E.; Montalvo, M.; Lee, D.S.; Whisenant, J.G.; Gaffney, K.; et al. Adverse Events in Patients Treated with Neoadjuvant Chemo/Immunotherapy for Triple Negative Breast Cancer: Results from Seven Academic Medical Centers. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2025, 213, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rios-Hoyo, A.; Dai, J.; Noel, T.; Blenman, K.R.M.; Park, T.; Pusztai, L. Immune-Related Adverse Events Are Associated with Better Event-Free Survival in a Phase I/II Clinical Trial of Durvalumab Concomitant with Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Early-Stage Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. ESMO Open 2025, 10, 104494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, N.; Lee, S.-J.; Ohtani, S.; Im, Y.-H.; Lee, E.-S.; Yokota, I.; Kuroi, K.; Im, S.-A.; Park, B.-W.; Kim, S.-B.; et al. Adjuvant Capecitabine for Breast Cancer after Preoperative Chemotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 2147–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.P.; Sevilimedu, V.; Jones, V.M.; Abuhadra, N.; Montagna, G.; Plitas, G.; Morrow, M.; Downs-Canner, S.M. Impact of Neoadjuvant Chemoimmunotherapy on Surgical Outcomes and Time to Radiation in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 31, 5180–5188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helal, C.; Djerroudi, L.; Ramtohul, T.; Laas, E.; Vincent-Salomon, A.; Jin, M.; Seban, R.-D.; Bieche, I.; Bello-Roufai, D.; Bidard, F.-C.; et al. Clinico-Pathological Factors Predicting Pathological Response in Early Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. npj Breast Cancer 2025, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawate, T.; Iwaya, K.; Kikuchi, R.; Kaise, H.; Oda, M.; Sato, E.; Hiroi, S.; Matsubara, O.; Kohno, N. DJ-1 Protein Expression as a Predictor of Pathological Complete Remission after Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Breast Cancer Patients. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2013, 139, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivina, E.; Blumberga, L.; Purkalne, G.; Irmejs, A. Pathological Complete Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Triple Negative Breast Cancer-Single Hospital Experience. Hered. Cancer Clin. Pract. 2023, 21, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Ende, N.S.; Nguyen, A.H.; Jager, A.; Kok, M.; Debets, R.; van Deurzen, C.H.M. Triple-Negative Breast Cancer and Predictive Markers of Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon-Ferre, R.A.; Dimitroff, K.; Yau, C.; Giridhar, K.V.; Mukhtar, R.; Hirst, G.; Hylton, N.; Perlmutter, J.; DeMichele, A.; Yee, D.; et al. Combined Prognostic Impact of Initial Clinical Stage and Residual Cancer Burden after Neoadjuvant Systemic Therapy in Triple-Negative and HER2-Positive Breast Cancer: An Analysis of the I-SPY2 Randomized Clinical Trial. Breast Cancer Res. 2025, 27, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Marcke, C.; Pogoda, K.; Fenton, H.; Vallet, M.; Plavc, G.; Borges, M.; Yousuf, H.; Dumas, E.; Berliere, M.; Ciliberto, G.; et al. Association between Neoadjuvant Paclitaxel Dose Intensity and Outcomes in Early Triple-Negative and HER2-Positive Breast Cancer: A Real-World Data Analysis. ESMO Real. World Data Digit. Oncol. 2025, 9, 100158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelico, G.; Broggi, G.; Tinnirello, G.; Puzzo, L.; Vecchio, G.M.; Salvatorelli, L.; Memeo, L.; Santoro, A.; Farina, J.; Mulé, A.; et al. Tumor Infiltrating Lymphocytes (TILS) and PD-L1 Expression in Breast Cancer: A Review of Current Evidence and Prognostic Implications from Pathologist’s Perspective. Cancers 2023, 15, 4479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid, P.; Cortes, J.; Dent, R.; Pusztai, L.; McArthur, H.; Kümmel, S.; Bergh, J.; Denkert, C.; Park, Y.H.; Hui, R.; et al. Event-Free Survival with Pembrolizumab in Early Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Stecklein, S.R.; Yoder, R.; Staley, J.M.; Schwensen, K.; O’Dea, A.; Nye, L.; Satelli, D.; Crane, G.; Madan, R.; et al. Clinical and Biomarker Findings of Neoadjuvant Pembrolizumab and Carboplatin Plus Docetaxel in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: NeoPACT Phase 2 Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2024, 10, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Pre-PSM | Post-PSM | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No-Immunotherapy (N = 143) | Immunotherapy (N = 65) | p | No-Immunotherapy (N = 65) | Immunotherapy (N = 65) | p | |

| Age at diagnosis | 0.027 1 | 0.905 1 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 48.9 (12.7) | 44.9 (10.0) | 45.2 (11.8) | 44.9 (10.0) | ||

| Range | 19.0–84.0 | 22.0–68.0 | 19.0–65.0 | 22.0–65.0 | ||

| BMI | 0.608 1 | 0.913 1 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 31.0 (6.5) | 30.5 (6.6) | 30.4 (6.0) | 30.5 (6.6) | ||

| Range | 20.0–50.3 | 19.6–56.7 | 20.0–45.0 | 19.6–56.7 | ||

| Smoking Status | 0.592 2 | 0.684 2 | ||||

| No | 105.0 (73.4%) | 50.0 (76.9%) | 48.0 (73.8%) | 50.0 (76.9%) | ||

| Yes | 38.0 (26.6%) | 15.0 (23.1%) | 17.0 (26.2%) | 15.0 (23.1%) | ||

| Comorbidity | 0.244 2 | 0.848 2 | ||||

| No | 87.0 (60.8%) | 45.0 (69.2%) | 46.0 (70.8%) | 45.0 (69.2%) | ||

| Yes | 56.0 (39.2%) | 20.0 (30.8%) | 19.0 (29.2%) | 20.0 (30.8%) | ||

| Clinical T | 0.086 2 | 0.349 2 | ||||

| 1 | 19.0 (13.3%) | 4.0 (4.6.1%) | 7.0 (10.8%) | 4.0 (6.2%) | ||

| 2 | 76.0 (53.1%) | 35.0 (53.8%) | 27.0 (41.5%) | 35.0 (53.8%) | ||

| 3 | 43.0 (30.1%) | 20.0 (30.8%) | 27.0 (41.5%) | 20.0 (30.8%) | ||

| 4 | 5.0 (3.5%) | 6.0 (9.2%) | 4.0 (6.2%) | 6.0 (9.2%) | ||

| Clinical N | 0.516 2 | 0.742 2 | ||||

| 0 | 65.0 (45.5%) | 26.0 (40.0%) | 23.0 (35.4%) | 26.0 (40.0%) | ||

| 1 | 64.0 (44.8%) | 35.0 (53.8%) | 36.0 (55.4%) | 35.0 (53.8%) | ||

| 2 | 12.0 (8.4%) | 4.0 (6.2%) | 6.0 (9.2%) | 4.0 (6.2%) | ||

| 3 | 2.0 (1.4%) | 0.0 (0.0%) | - | - | ||

| Clinical stage | 0.302 2 | 0.899 2 | ||||

| 1A | 14.0 (9.8%) | 3.0 (4.6%) | 4.0 (6.2%) | 3.0 (4.6%) | ||

| 2A | 42.0 (29.4%) | 16.0 (24.6%) | 13.0 (20.0%) | 16.0 (24.6%) | ||

| 2B | 48.0 (33.6%) | 22.0 (33.8%) | 25.0 (38.5%) | 22.0 (33.8%) | ||

| 3A | 32.0 (22.4%) | 18.0 (27.7%) | 19.0 (29.2%) | 18.0 (27.7%) | ||

| 3B | 5.0 (3.5%) | 6.0 (9.2%) | 4.0 (6.2%) | 6.0 (9.2%) | ||

| 3C | 2.0 (1.4%) | 0.0 (0.0%) | - | - | ||

| Grade | 0.498 2 | 0.329 2 | ||||

| 1 | 3.0 (2.1%) | 0.0 (0.0%) | 1.0 (1.5%) | 0.0 (0.0%) | ||

| 2 | 25.0 (17.5%) | 12.0 (18.5%) | 17.0 (26.2%) | 12.0 (18.5%) | ||

| 3 | 115.0 (80.4%) | 53.0 (81.5%) | 47.0 (72.3%) | 53.0 (81.5%) | ||

| Histopathology | 0.602 2 | 0.698 2 | ||||

| DCIS | 2.0 (1.4%) | 0.0 (0.0%) | ||||

| IDC | 130.0 (90.9%) | 61.0 (93.8%) | 62.0 (95.4%) | 61.0 (93.8%) | ||

| ILC | 2.0 (1.4%) | 0.0 (0.0%) | ||||

| IMC | 9.0 (6.3%) | 4.0 (6.2%) | 3.0 (4.6%) | 4.0 (6.2%) | ||

| Surgery | 0.116 2 | 0.674 2 | ||||

| BCS | 65.0 (45.5%) | 23.0 (35.4%) | 20.0 (30.8%) | 23.0 (35.4%) | ||

| Mastectomy with reconstruction | 21.0 (14.7%) | 17.0 (26.2%) | 15.0 (23.1%) | 17.0 (26.2%) | ||

| Mastectomy without reconstruction | 57.0 (39.9%) | 25.0 (38.5%) | 30.0 (46.2%) | 25.0 (38.5%) | ||

| Axillary surgery | <0.001 2 | <0.001 2 | ||||

| AD | 86 (60.1%) | 21 (33.9%) | 41 (64.1%) | 21 (33.9%) | ||

| SLNBx | 57 (40.6%) | 41 (66.1%) | 23 (35.9%) | 41 (66.1%) | ||

| ASA | 0.475 2 | 0.793 2 | ||||

| 1 | 1 (0.7%) | 0.0 (0.0%) | ||||

| 2 | 134.0 (93.7%) | 60.0 (92.3%) | 61.0 (93.8%) | 60.0 (92.3%) | ||

| 3 | 7.0 (4.9%) | 5.0 (7.7%) | 4.0 (6.1%) | 5.0 (7.7%) | ||

| 4 | 1 (0.7%) | 0.0 (0.0%) | ||||

| Immune-Related Adverse Event | N (%) |

|---|---|

| No | 32 (49.2%) |

| Yes | 33 (50.8%) |

| If yes, what is the type | |

| Hypothyroidism | 23 (35.4%) |

| Adrenal insufficiency | 6 (9.2%) |

| Colitis | 1 (1.5%) |

| Skin toxicity | 1 (1.5%) |

| Pneumonitis | 2 (3.1%) |

| Outcome | No-Immunotherapy (N = 65) | Immunotherapy (N = 65) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| pCR | <0.001 1 | ||

| No | 59 (90.8%) | 22 (33.8%) | |

| Yes | 6 (9.2%) | 43 (66.2%) | |

| Pathologic T Stage (pT) | <0.001 1 | ||

| pT4 | 7 (10.8%) | 1 (1.5%) | |

| pT3 | 18 (27.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| pT2 | 7 (10.8%) | 5 (7.7%) | |

| pT1 | 26 (40.0%) | 14 (21.5%) | |

| pT0 | 7 (10.8%) | 45 (69.2%) | |

| Pathologic N Stage (pN) | <0.001 1 | ||

| pN0 | 30 (46.9%) | 55 (88.7%) | |

| pN1 | 13 (20.3%) | 4 (6.5%) | |

| pN2 | 12 (18.8%) | 3 (4.8%) | |

| pN3 | 9 (14.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| LN positivity ratio | <0.001 2 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 24.3 (33.1) | 2.2 (7.7) | |

| Range | 0.0–100.0 | 0.0–41.2 |

| No-Immunotherapy (N = 65) | Immunotherapy (N = 65) | Total (N = 130) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjuvant Radiotherapy | 0.527 1 | |||

| No | 16.0 (24.6%) | 13.0 (20.0%) | 29.0 (22.3%) | |

| Yes | 49.0 (75.4%) | 52.0 (80.0%) | 101.0 (77.7%) | |

| Adjuvant systemic therapy | <0.001 1 | |||

| No | 49.0 (75.4%) | 11.0 (16.9%) | 60.0 (46.2%) | |

| Yes | 16.0 (24.6%) | 54.0 (83.1%) | 70.0 (53.8%) | |

| Type of systemic therapy | - | |||

| Immunotherapy | 0.0 (0.0%) | 51.0 (78.5%) | 51.0 (39.2%) | |

| Chemotherapy | 16.0 (24.6%) | 3.0 (4.6%) | 19.0 (14.6%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Masri, M.; Safi, Y.; Kardan, R.; Mustafa, D.; Ramadan, O.; AlMasri, R. Adding Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy to Chemotherapy in Non-Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: A Propensity-Matched Cohort Study from a Tertiary Cancer Center. Cancers 2025, 17, 3933. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243933

Al-Masri M, Safi Y, Kardan R, Mustafa D, Ramadan O, AlMasri R. Adding Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy to Chemotherapy in Non-Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: A Propensity-Matched Cohort Study from a Tertiary Cancer Center. Cancers. 2025; 17(24):3933. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243933

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Masri, Mahmoud, Yasmin Safi, Ramiz Kardan, Daliana Mustafa, Ola Ramadan, and Rama AlMasri. 2025. "Adding Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy to Chemotherapy in Non-Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: A Propensity-Matched Cohort Study from a Tertiary Cancer Center" Cancers 17, no. 24: 3933. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243933

APA StyleAl-Masri, M., Safi, Y., Kardan, R., Mustafa, D., Ramadan, O., & AlMasri, R. (2025). Adding Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy to Chemotherapy in Non-Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: A Propensity-Matched Cohort Study from a Tertiary Cancer Center. Cancers, 17(24), 3933. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243933