PROSTest, a Novel Liquid Biopsy Molecular Assay, Accurately Guides Prostate Cancer Biopsy Decision-Making in Men with Elevated PSA Irrespective of DRE Findings

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Consent

2.3. Subjects

2.4. DRE

2.5. Blood Collection

2.6. PROSTest Measurements

2.7. Statistics

3. Results

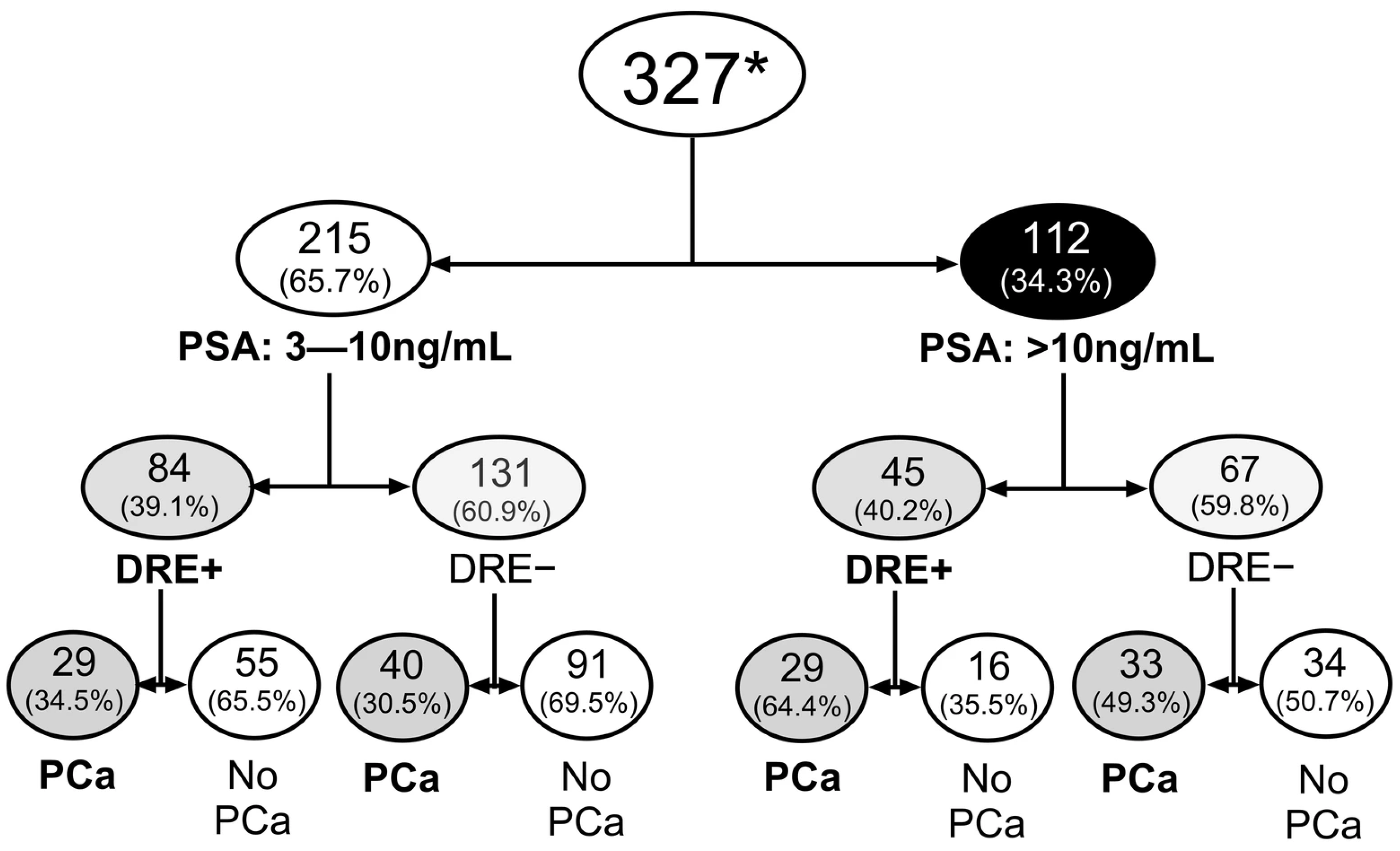

3.1. Cohort Characteristics and Cancer Detection

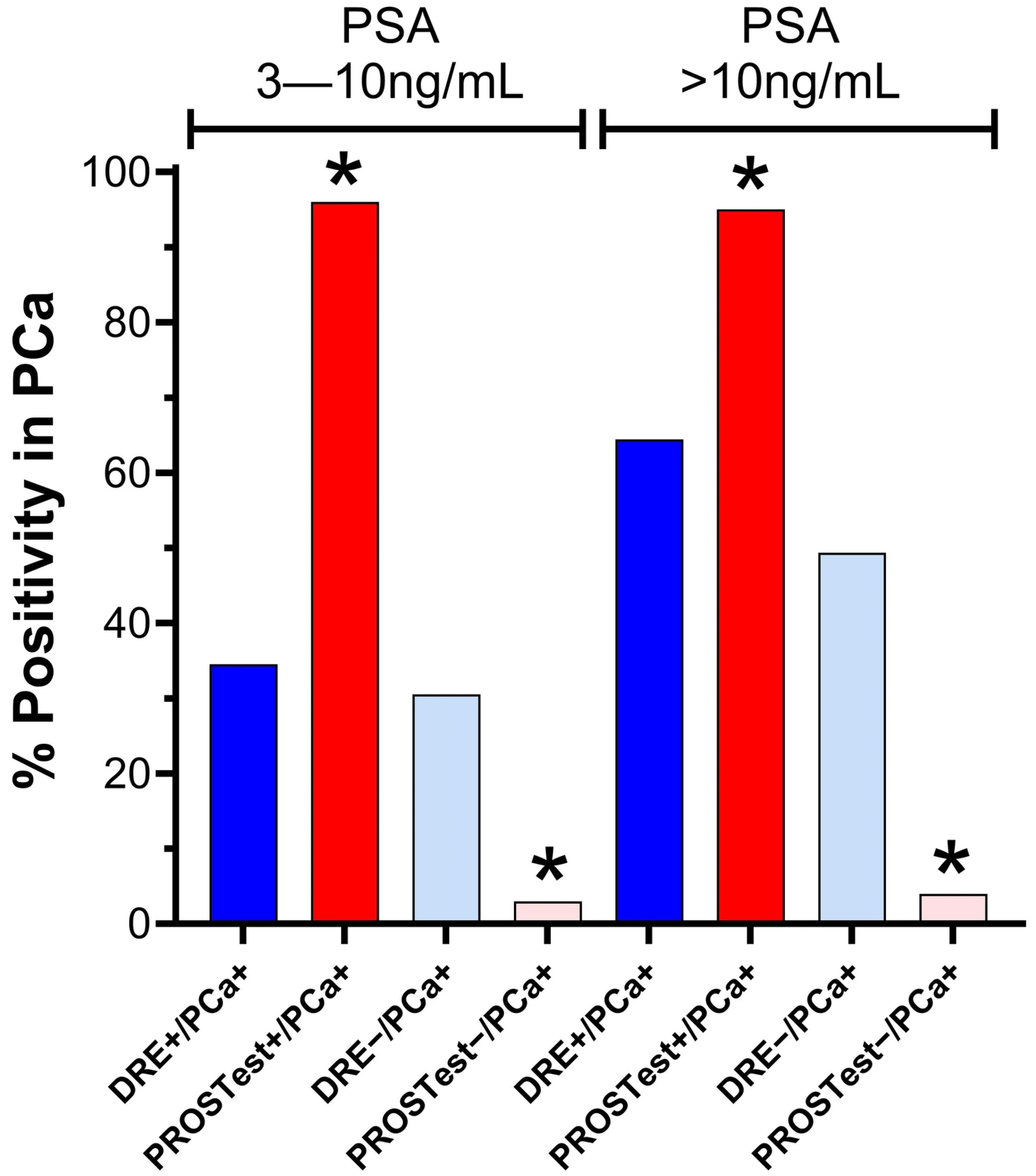

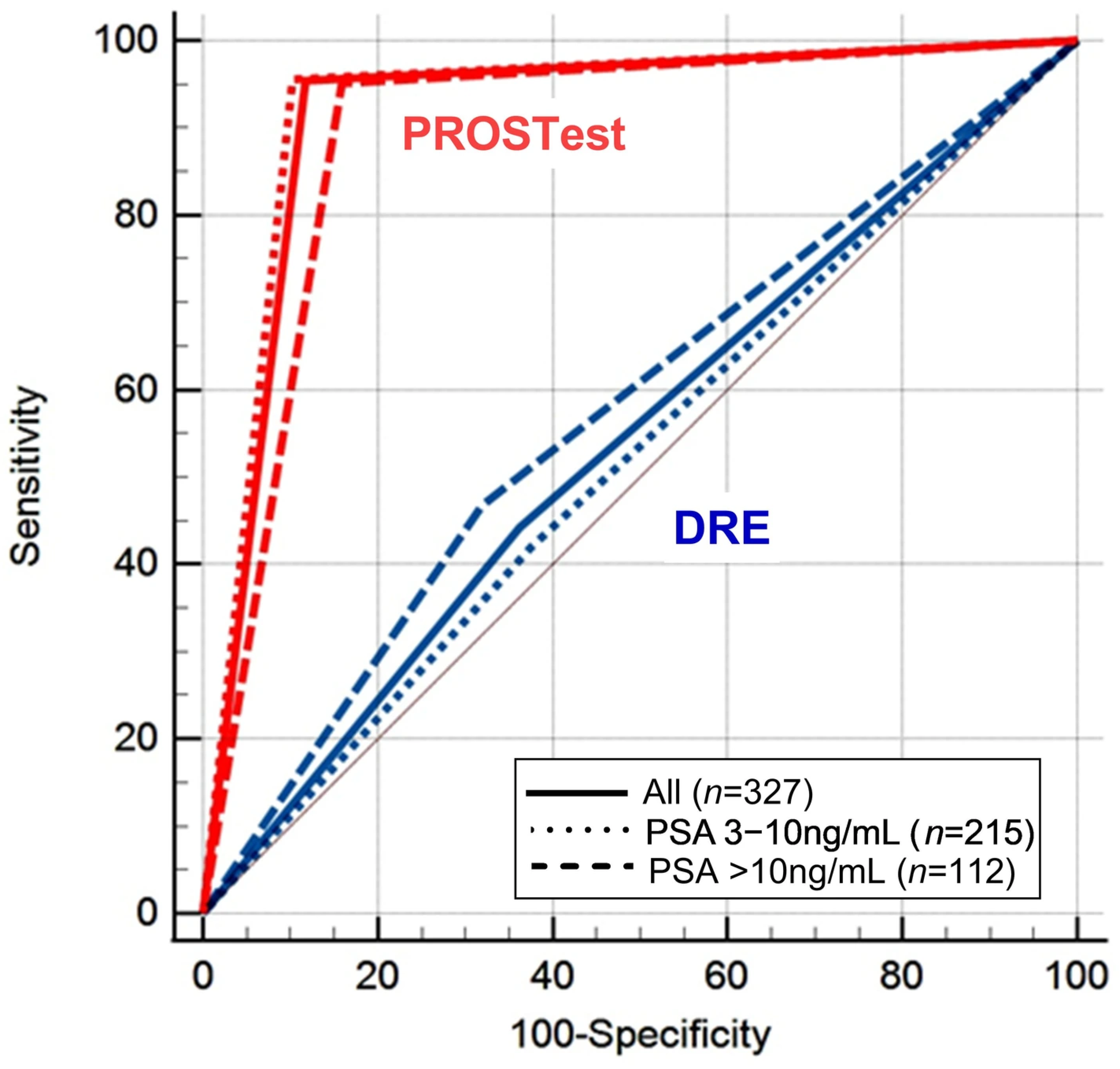

Diagnostic Performance of DRE

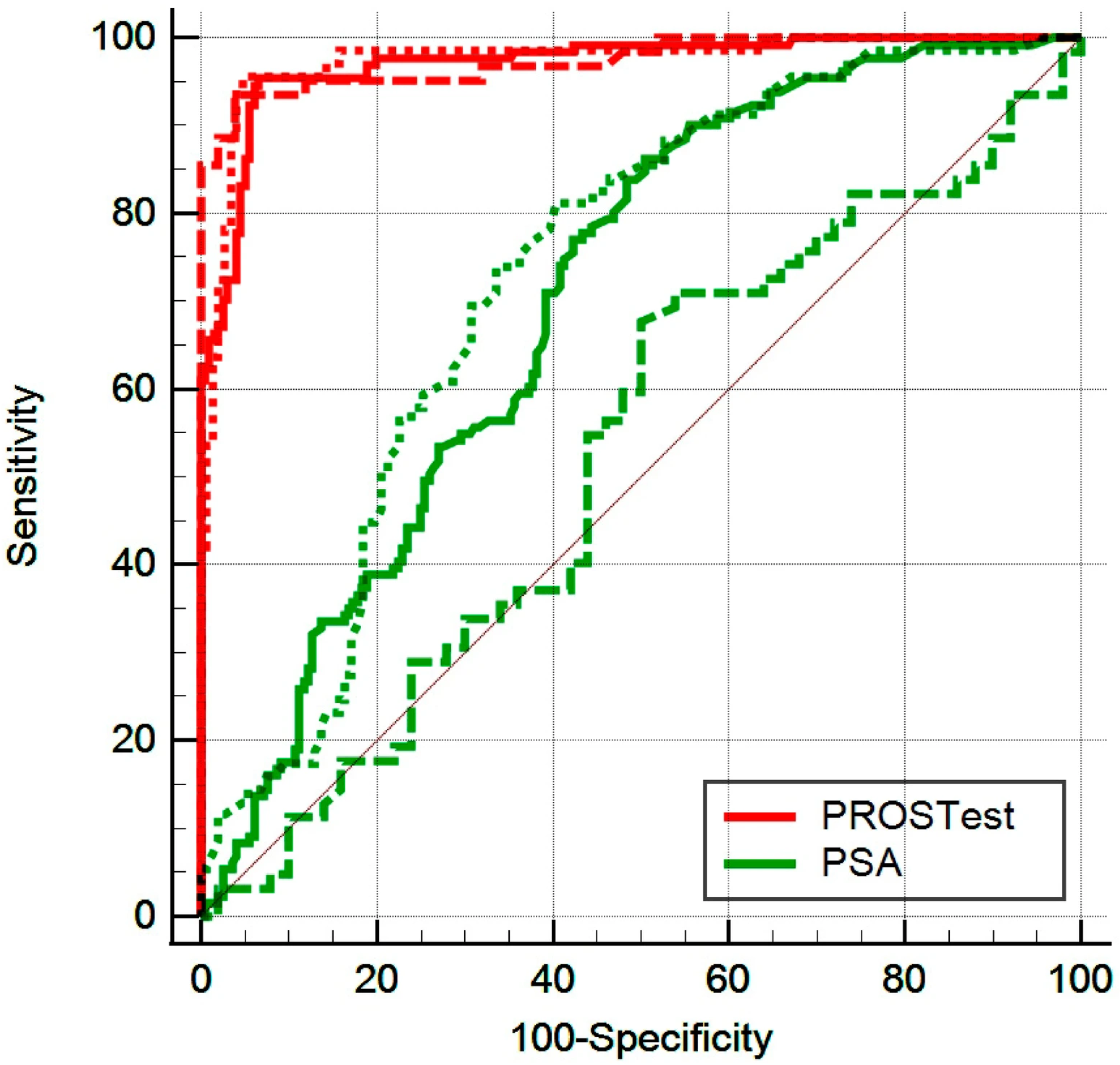

3.2. Diagnostic Performance of PROSTest

3.2.1. Quartile Evaluation of PROSTest

3.2.2. Cohort 1: Subjects with PSA 3–10 ng/mL

3.2.3. Cohort 2: Subjects with PSA > 10 ng/mL

3.3. Multivariate Analysis: PROSTest as the Principal Predictor of Prostate Cancer

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DRE | Digital Rectal Examination |

| PSA | Prostate Specific Antigen |

| PPV | Positive Predictive Value |

| NPV | Negative Predictive Value |

| CDR | Cancer Detection Rate |

| BPH | Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia |

| PCa | Prostate Cancer |

| AUROC | Area Under the Receiver Operator Curve |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| ROC | Receiver Operator Curve |

| SE | Standard Error |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| RT | Reverse Transcription |

| ELISA | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| mRNA | Messenger Ribonucleic Acid |

References

- James, N.D.; Tannock, I.; N’Dow, J.; Feng, F.; Gillessen, S.; Ali, S.A.; Trujilo, B.; Al-Lazikani, B.; Attard, G.; Bray, F.; et al. The Lancet Commission on prostate cancer: Planning for the surge in cases. Lancet 2024, 403, 1683–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culp, M.B.; Soerjomataram, I.; Efstathiou, J.A.; Bray, F.; Jemal, A. Recent Global Patterns in Prostate Cancer Incidence and Mortality Rates. Eur. Urol. 2020, 77, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergengren, O.; Pekala, K.R.; Matsoukas, K.; Fainberg, J.; Mungovan, S.F.; Bratt, O.; Bray, F.; Brawley, O.; Luckenbaugh, A.N.; Mucci, L.; et al. 2022 Update on Prostate Cancer Epidemiology and Risk Factors-A Systematic Review. Eur. Urol. 2023, 84, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Cancer Society. Key Statistics for Prostate Cancer; American Cancer Society, Ed.; American Cancer Society: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Stamey, T.A.; Yang, N.; Hay, A.R.; McNeal, J.E.; Freiha, F.S.; Redwine, E. Prostate-specific antigen as a serum marker for adenocarcinoma of the prostate. N. Engl. J. Med. 1987, 317, 909–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semjonow, A.; Brandt, B.; Oberpenning, F.; Roth, S.; Hertle, L. Discordance of assay methods creates pitfalls for the interpretation of prostate-specific antigen values. Prostate Suppl. 1996, 7, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, I.M.; Pauler, D.K.; Goodman, P.J.; Tangen, C.M.; Lucia, M.S.; Parnes, H.L.; Minasian, L.M.; Ford, L.G.; Lippman, S.M.; Crawford, E.D.; et al. Prevalence of prostate cancer among men with a prostate-specific antigen level < or =4.0 ng per milliliter. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 2239–2246. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.J.; Consedine, N.S.; Spencer, B.A. Barriers and facilitators to digital rectal examination screening among African-American and African-Caribbean men. Urology 2011, 77, 891–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consedine, N.S.; Morgenstern, A.H.; Kudadjie-Gyamfi, E.; Magai, C.; Neugut, A.I. Prostate cancer screening behavior in men from seven ethnic groups: The fear factor. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2006, 15, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Kunz, R.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Vist, G.E.; Liberati, A.; Shünemann, H.J.; GRADE Working Group. Going from evidence to recommendations. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 2008, 336, 1049–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCCN. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Prostate Cancer Early Detection, 2.2025 ed.; NCCN: Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA, 2025; p. 81. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalhal, G.F.; Smith, D.S.; Mager, D.E.; Ramos, C.; Catalona, W.J. Digital rectal examination for detecting prostate cancer at prostate specific antigen levels of 4 ng/mL. or less. J. Urol. 1999, 161, 835–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosselaar, C.; Roobol, M.J.; Roemeling, S.; Schröder, F.H. The role of the digital rectal examination in subsequent screening visits in the European randomized study of screening for prostate cancer (ERSPC), Rotterdam. Eur. Urol. 2008, 54, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okotie, O.T.; Roehl, K.A.; Han, M.; Loeb, S.; Gashti, S.N.; Catalona, W.J. Characteristics of prostate cancer detected by digital rectal examination only. Urology 2007, 70, 1117–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera-Caceres, J.O.; Wettstein, M.S.; Goldberg, H.; Toi, A.; Chandrasekar, T.; Woon, D.T.S.; Ahmad, A.E.; Sanmamed-Salgado, N.; Alhunaidi, O.; Ajib, K.; et al. Utility of digital rectal examination in a population with prostate cancer treated with active surveillance. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2020, 14, E453–E457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prebay, Z.J.; Medairos, R.; Doolittle, J.; Langenstroer, P.; Jacobsohn, K.; See, W.A.; Johnson, S.C. The prognostic value of digital rectal exam for the existence of advanced pathologic features after prostatectomy. Prostate 2021, 81, 1064–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modlin, I.M.; Kidd, M.; Drozdov, I.A.; Boegemann, M.; Bodei, L.; Kunikowska, J.; Malczweska, A.; Bernemann, C.; Koduru, S.V.; Rahbar, K. Development of a multigenomic liquid biopsy (PROSTest) for prostate cancer in whole blood. Prostate 2024, 84, 850–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filella, X.; Foj, L.; Alcover, J.; Augé, J.M.; Molina, R.; Jiménez, W. The influence of prostate volume in prostate health index performance in patients with total PSA lower than 10 μg/L. Clin. Chim. Acta Int. J. Clin. Chem. 2014, 436, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalona, W.J.; Partin, A.W.; Sanda, M.G.; Wei, J.T.; Klee, G.G.; Bangma, C.H.; Slawin, K.M.; Marks, L.S.; Loeb, S.; Broyles, D.L.; et al. A multicenter study of [-2]pro-prostate specific antigen combined with prostate specific antigen and free prostate specific antigen for prostate cancer detection in the 2.0 to 10.0 ng/ml prostate specific antigen range. J. Urol. 2011, 185, 1650–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steuber, T.; Nurmikko, P.; Haese, A.; Pettersson, K.; Graefen, M.; Hammerer, P.; Huland, H.; Lilja, H. Discrimination of benign from malignant prostatic disease by selective measurements of single chain, intact free prostate specific antigen. J. Urol. 2002, 168, 1917–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hatano, K.; Nonomura, N. Liquid Biomarkers in Prostate Cancer Diagnosis: Current Status and Emerging Prospects. World J. Men’s Health 2025, 43, 8–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahbar, K.; Kidd, M.; Prasad, V.; David Rosin, R.; Drozdov, I.; Halim, A. Clinical Sensitivity and Specificity of the PROSTest in an American Cohort. Prostate 2025, 85, 558–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, M.; Rempega, G.; Kepinski, M.; Slomian, S.; Mlynarek, K.; Halim, A.B. Utility of the PROSTest, a Novel Blood-Based Molecular Assay, Versus PSA for Prostate Cancer Stratification and Detection of Disease. Prostate 2025. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaeffer, E.M.; Srinivas, S.; Adra, N.; An, Y.; Bitting, R.; Chapin, B.; Cheng, H.H.; D’Amico, A.V.; Desai, N.; Dorff, T.; et al. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Prostate Cancer, Version 3.2024. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. JNCCN 2024, 22, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moses, K.A.; Sprenkle, P.C.; Bahler, C.; Box, G.; Carlsson, S.V.; Catalona, W.J.; Dahl, D.M.; Dall’Era, M.; Davis, J.W.; Drake, B.F.; et al. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Prostate Cancer Early Detection, Version 1.2023. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. JNCCN 2023, 21, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canto, E.I.; Slawin, K.M. Early management of prostate cancer: How to respond to an elevated PSA? Annu. Rev. Med. 2002, 53, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, D. Prostate cancer screening in African American men: Barriers and methods for improvement. Am. J. Men’s Health 2008, 2, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorentz, J.; Woollcombe, J.; Loblaw, A.; Liu, S.; Vesprini, D. Screening guidelines for individuals at increased risk for prostate cancer. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2024, 18, E301–E307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, M.; Drozdov, I.A.; Matar, S.; Gurunlian, N.; Ferranti, N.J.; Malczewska, A.; Bennett, P.; Bodei, L.; Modlin, I.M. Utility of a ready-to-use PCR system for neuroendocrine tumor diagnosis. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsukawa, A.; Yanagisawa, T.; Bekku, K.; Kardoust Parizi, M.; Laukhtina, E.; Klemm, J.; Chiujdea, S.; Mori, K.; Kimura, S.; Fazekas, T.; et al. Comparing the Performance of Digital Rectal Examination and Prostate-specific Antigen as a Screening Test for Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2024, 7, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naji, L.; Randhawa, H.; Sohani, Z.; Dennis, B.; Lautenbach, D.; Kavanagh, O.; Bawor, M.; Banfield, L.; Proffeto, J. Digital Rectal Examination for Prostate Cancer Screening in Primary Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann. Fam. Med. 2018, 16, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | OR Variable (95% CI) | Z-Statistic | p-Value Variable |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 (1.21–9.88) | 0.011 (0.002–0.08) | 4.454 | <0.0001 |

| Q2 (9.89–39.40) | 0.036 (0.011–0.115) | 5.547 | <0.0001 |

| Q3 (39.41–85.55) | 2.404 (1.451–3.986) | 3.402 | <0.0001 |

| Q4 (85.56–99.20) | 614.3 (37.46–10,075.1) | 3.402 | <0.0001 |

| Q3 + Q4 (39.41–99.20) | 136.44 (47.38–392.89) | 9.110 | <0.0001 |

| PROSTest + ve (≥50) | 156.7 (61.98–396.17) | 10.681 | <0.0001 |

| PSA 3–10 ng/mL | PSA > 10 ng/mL | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DRE+/ PROS+ | DRE+ /PROS− | DRE−/ PROS+ | DRE−/ PROS− | DRE+/ PROS+ | DRE+ /PROS− | DRE−/ PROS+ | DRE−/ PROS− | |

| Number | 32 | 52 | 49 | 82 | 30 | 15 | 37 | 30 |

| PCa | 28 | 1 | 38 | 2 | 28 | 1 | 31 | 2 |

| Non-PCa | 4 | 51 | 11 | 80 | 2 | 14 | 6 | 28 |

| Sensitivity | 96.6% (82.2–99.9%) | 95% (83.1–99.4%) | 96.6% (82.2–99.9%) | 93.9% (79.8–99.3%) | ||||

| Specificity | 92.7% (82.4–98.0%) | 87.9% (79.4–93.8%) | 87.5% (61.6–98.5%) | 82.4% (65.5–93.2%) | ||||

| PPV | 87.5% (73.1–94.8%) | 77.6% (66.4–85.8%) | 93.3% (79.3–98.1%) | 83.8% (71.3–91.5%) | ||||

| NPV | 98.1% (88.1–99.7%) | 97.6% (91.2–99.4%) | 93.3% (66.9–99.0%) | 93.3% (78.4–98.2%) | ||||

| Accuracy | 94.1% (86.7–98.0%) | 90.1% (83.6–94.6%) | 93.3% (81.7–98.6%) | 88.1% (77.8–94.7%) | ||||

| Cohort | AUC (PSA) | Sens/Spec | Cut-Off | AUC (PROS) | Sens/Spec | Cut-Off | Difference in AUC | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (n = 215) | 0.73 ± 0.035 | 81.2%/59.6% | >5.5 ng/mL | 0.97 ± 0.011 | 95.7%/95.2% | >60.06 | 0.245 ± 0.04 | <0.0001 |

| 2 (n = 112) | 0.53 ± 0.056 | 67.7%/50.0% | >14.9 ng/mL | 0.97 ± 0.013 | 93.6%/96.0% | >82.4 | 0.446 ± 0.06 | <0.0001 |

| All PSA (n = 327) | 0.70 ± 0.028 | 86.3%/49.5% | >5.9 ng/mL | 0.91 ± 0.001 | 95.4%/93.4% | >60.06 | 0.268 ± 0.03 | <0.0001 |

| Independent Variables | OR | 95% CI | Co- Efficient ±SE | Wald | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age > 75 years | 2.26 | 0.486 to 10.51 | 0.851 ± 0.78 | 1.08 | 0.30 |

| DRE + ve | 1.48 | 0.625 to 3.50 | 0.392 ± 0.44 | 0.79 | 0.37 |

| Family History | 0.30 | 0.092 to 0.965 | −1.209 ± 0.60 | 4.08 | 0.04 |

| PSA > 10 ng/mL | 1.78 | 0.765 to 4.144 | 0.577 ± 0.43 | 1.79 | 0.18 |

| PROSTest + ve | 154.0 | 59.5 to 398.9 | 5.037 ± 0.48 | 107.74 | <0.0001 |

| Constant | - | - | −3.616 ± 0.49 | 54.22 | <0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rogers, C.G.; Koduru, S.V.; Gulati, A.; Halim, A.B. PROSTest, a Novel Liquid Biopsy Molecular Assay, Accurately Guides Prostate Cancer Biopsy Decision-Making in Men with Elevated PSA Irrespective of DRE Findings. Cancers 2025, 17, 3908. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243908

Rogers CG, Koduru SV, Gulati A, Halim AB. PROSTest, a Novel Liquid Biopsy Molecular Assay, Accurately Guides Prostate Cancer Biopsy Decision-Making in Men with Elevated PSA Irrespective of DRE Findings. Cancers. 2025; 17(24):3908. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243908

Chicago/Turabian StyleRogers, Craig G., Srinivas V. Koduru, Anthony Gulati, and Abdel B. Halim. 2025. "PROSTest, a Novel Liquid Biopsy Molecular Assay, Accurately Guides Prostate Cancer Biopsy Decision-Making in Men with Elevated PSA Irrespective of DRE Findings" Cancers 17, no. 24: 3908. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243908

APA StyleRogers, C. G., Koduru, S. V., Gulati, A., & Halim, A. B. (2025). PROSTest, a Novel Liquid Biopsy Molecular Assay, Accurately Guides Prostate Cancer Biopsy Decision-Making in Men with Elevated PSA Irrespective of DRE Findings. Cancers, 17(24), 3908. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243908