Are Uterine Manipulators Harmful in Minimally Invasive Endometrial Cancer Surgery? A Retrospective Cohort Study †

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

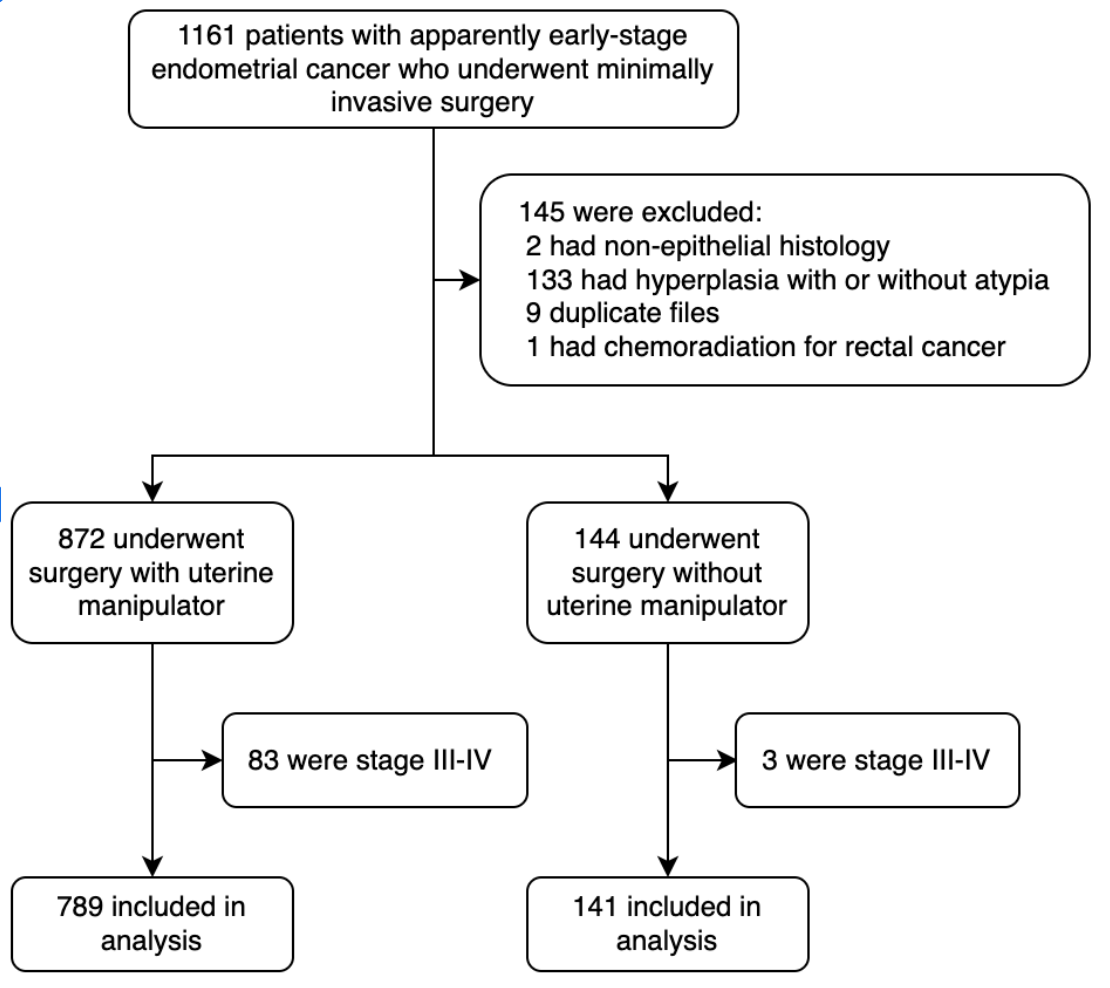

2. Materials and Methods

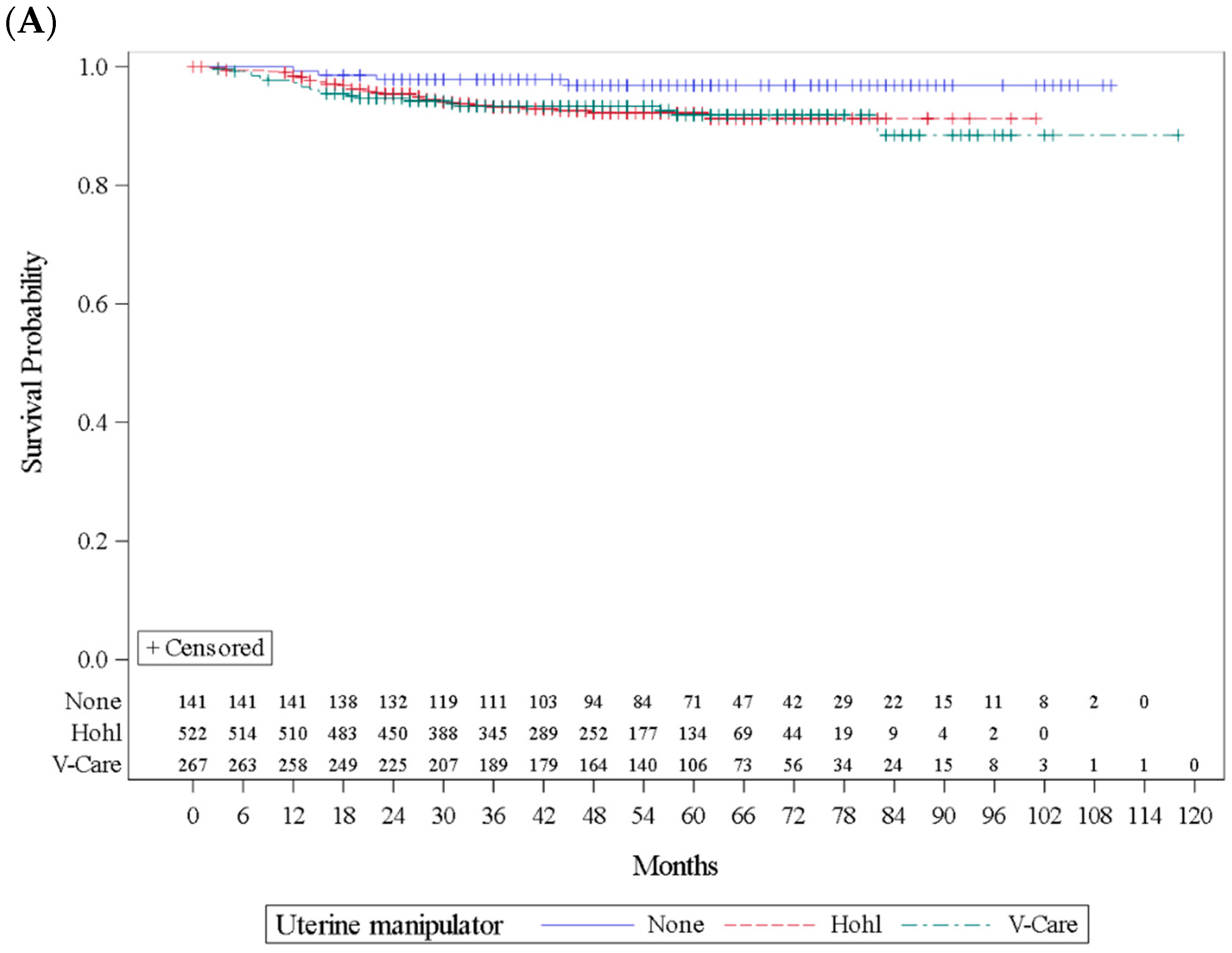

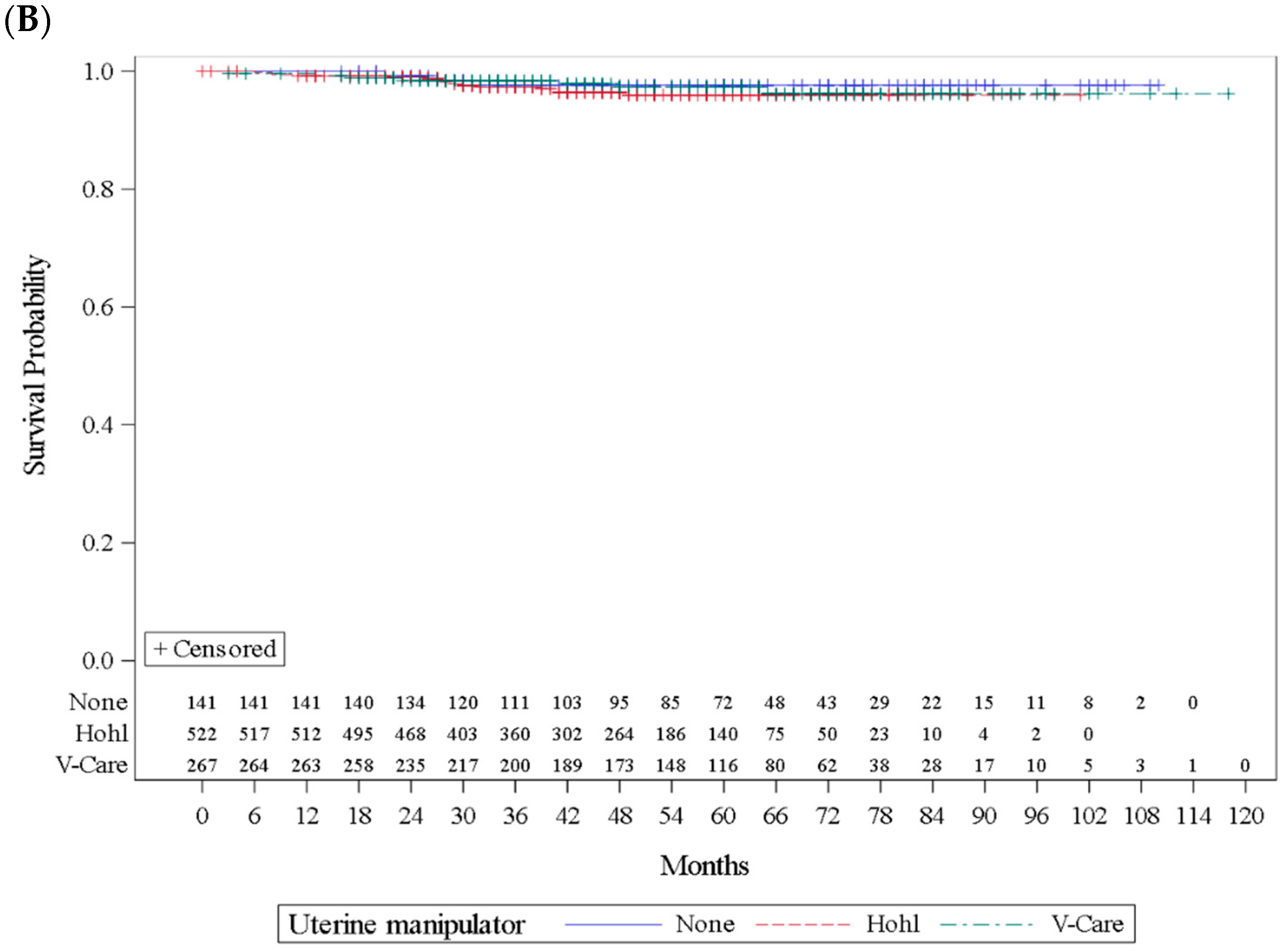

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel Khalek, Y.; Bitar, R.; Christoforou, C.; Garzon, S.; Tropea, A.; Biondi, A.; Sleiman, Z. Uterine manipulator in total laparoscopic hysterectomy: Safety and usefulness. Updates Surg. 2020, 72, 1247–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez, P.T.; Frumovitz, M.; Pareja, R.; Lopez, A.; Vieira, M.; Ribeiro, R.; Buda, A.; Yan, X.; Yao, S.; Chetty, N.; et al. Minimally Invasive versus Abdominal Radical Hysterectomy for Cervical Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 1895–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touhami, O.; Plante, M. Minimally Invasive Surgery for Cervical Cancer in Light of the LACC Trial: What Have We Learned? Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 1093–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padilla-Iserte, P.; Lago, V.; Tauste, C.; Diaz-Feijoo, B.; Gil-Moreno, A.; Oliver, R.; Coronado, P.; Martin-Salamanca, M.B.; Pantoja-Garrido, M.; Marcos-Sanmartin, J.; et al. Impact of uterine manipulator on oncological outcome in endometrial cancer surgery. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 224, 65.e1–65.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uccella, S.; Bonzini, M.; Malzoni, M.; Fanfani, F.; Palomba, S.; Aletti, G.; Corrado, G.; Ceccaroni, M.; Seracchioli, R.; Shakir, F.; et al. The effect of a uterine manipulator on the recurrence and mortality of endometrial cancer: A multi-centric study by the Italian Society of Gynecological Endoscopy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 216, 592.e1–592.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Uterine Cancer (Version 1.2024). Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/uterine.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Pecorelli, S. Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the vulva, cervix, and endometrium. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2009, 105, 103–104, Erratum in Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2010, 108, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, S.; Hori, K.; Tashima, L.; Yoshimura, M.; Ito, K. Multiple metastases after laparoscopic surgery for early-stage endometrial cancer: A case report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2020, 76, 552–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosse, T.; Peters, E.E.; Creutzberg, C.L.; Jurgenliemk-Schulz, I.; Jobsen, J.; Mens, J.W.; Lutgens, L.; Steen-Basanik, E.; Smit, V.; Nout, R. Substantial lymph-vascular space invasion (LVSI) is a significant risk factor for recurrence in endometrial cancer—A pooled analysis of PORTEC 1 and 2 trials. Eur. J. Cancer 2015, 51, 1742–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scutiero, G.; Vizzielli, G.; Taliento, C.; Benardi, G.; Martinello, R.; Cianci, S.; Riemma, G.; Scambia, G.; Greco, P. Influence of uterine manipulator on oncological outcome in minimally invasive surgery of endometrial cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 48, 2112–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana-Bertó, R.; Padilla-Iserte, P.; Lago, V.; Tauste, C.; Diaz-Feijoo, B.; Cabrera, S.; Oliver-Perez, R.; Coronado, P.; Martin-Salamanca, M.; Pantoja-Garrido, M.; et al. Endometrial cancer: Predictors and oncological safety of tumor tissue manipulation. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2024, 26, 1098–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krizova, A.; Clarke, B.A.; Bernardini, M.Q.; James, S.; Kalloger, S.; Boerner, S.; Mulligan, A.M. Histologic artifacts in abdominal, vaginal, laparoscopic, and robotic hysterectomy specimens: A blinded, retrospective review. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2011, 35, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, J.L.; Piedmonte, M.R.; Spirtos, N.M.; Eisenkop, S.; Schlaerth, J.; Mannel, R.; Barakat, R.; Pearl, M.; Sharma, S. Recurrence and survival after random assignment to laparoscopy versus laparotomy for comprehensive surgical staging of uterine cancer: Gynecologic Oncology Group LAP2 Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 695–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janda, M.; Gebski, V.; Davies, L.C.; Forder, P.; Brand, A.; Hogg, R.; Jobling, T.; Land, R.; Manolitsas, T.; Nascimento, M.; et al. Effect of Total Laparoscopic Hysterectomy vs Total Abdominal Hysterectomy on Disease-Free Survival Among Women with Stage I Endometrial Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2017, 317, 1224–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renaud, M.C.; Sebastianelli, A.; Grégoire, J.; Plante, M. Five-Year Experience in the Surgical Treatment of Endometrial Cancer: Comparing Laparotomy with Robotic and Minimally Invasive Hysterectomy. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2022, 44, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feigenberg, T.; Cormier, B.; Gotlieb, W.H.; Jegatheeswaran, K.; Helpman, L.; Kim, S.; Lau, S.; May, T.; Saab, D.; Plante, M.; et al. Factors associated with an increased risk of recurrence in patients diagnosed with high-grade endometrial cancer undergoing minimally invasive surgery: A study of the society of gynecologic oncology of Canada (GOC) community of practice (CoP). Gynecol. Oncol. 2021, 162, 606–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uccella, S.; Puppo, A.; Ghezzi, F.; Zorzato, P.C.; Ceccaroni, M.; Mandato, V.; Berretta, R.; Camanni, M.; Seracchioli, R.; Perrone, A.M.; et al. A randomized controlled trial on the oncologic outcomes of use of the intrauterine manipulator in the treatment of apparent uterine-confined endometrial carcinoma: The MANEC Trial. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2024, 34, 1971–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Côté, M. Are Uterine Manipulators Harmful in Minimally Invasive Surgery (MIS) for Endometrial Cancer? A Retrospective Cohort Study. In Proceedings of the IGCS Annual Global Meeting, New York, NY, USA, 29 September–1 October 2022. [Google Scholar]

| Frequency Table | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Uterine Manipulator | n | % * |

| Uterine manipulator | None V-Care | 141 267 | 15.2 28.7 |

| Hohl | 522 | 56.1 | |

| Uterine Manipulator | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Hohl | V-Care | ||||||

| Variable | Level | n/N | % | n/N | % | n/N | % | p-Value 1 |

| FIGO 2009 staging | 1A | 108/141 | 76.6 | 428/522 | 82.0 | 211/267 | 79.0 | 0.4200 |

| 1B | 27/141 | 19.1 | 83/522 | 15.9 | 46/267 | 17.2 | ||

| 2 | 6/141 | 4.3 | 11/522 | 2.1 | 10/267 | 3.7 | ||

| Myometrial infiltration | None | 56/141 | 39.7 | 233/522 | 44.6 | 109/267 | 40.8 | 0.5643 |

| <50 | 57/141 | 40.4 | 203/522 | 38.9 | 103/267 | 38.6 | ||

| ≥50 | 28/141 | 19.9 | 86/522 | 16.5 | 55/267 | 20.6 | ||

| Histology | Carcinosarcoma | 1/141 | 0.7 | 17/522 | 3.3 | 2/267 | 0.7 | 0.0463 (!) |

| Clear cell | 2/141 | 1.4 | 3/522 | 0.6 | 4/267 | 1.5 | ||

| Dedifferentiated | 0/141 | 0.0 | 4/522 | 0.8 | 2/267 | 0.7 | ||

| Endometrioid | 133/141 | 94.3 | 447/522 | 85.6 | 240/267 | 89.9 | ||

| Mixed | 2/141 | 1.4 | 15/522 | 2.9 | 9/267 | 3.4 | ||

| Serous | 3/141 | 2.1 | 36/522 | 6.9 | 10/267 | 3.7 | ||

| Grade | 1 | 106/141 | 75.2 | 367/522 | 70.3 | 193/267 | 72.3 | 0.0327 * |

| 2 | 24/141 | 17.0 | 66/522 | 12.6 | 42/267 | 15.7 | ||

| 3 | 11/141 | 7.8 | 89/522 | 17.0 | 32/267 | 12.0 | ||

| Lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI) | No | 126/141 | 89.4 | 435/522 | 83.3 | 224/267 | 83.9 | 0.2084 |

| Yes | 15/141 | 10.6 | 87/522 | 16.7 | 43/267 | 16.1 | ||

| Positive peritoneal cytology | No | 133/141 | 94.3 | 500/522 | 95.8 | 254/267 | 95.1 | 0.7460 |

| Yes | 8/141 | 5.7 | 22/522 | 4.2 | 13/267 | 4.9 | ||

| Fallopian tube floaters | No | 132/140 | 94.3 | 492/522 | 94.3 | 227/267 | 85.0 | <0.0001 *** |

| Yes | 8/140 | 5.7 | 30/522 | 5.7 | 40/267 | 15.0 | ||

| Isolated tumor cells (ITCs) | No | 133/140 | 95.0 | 505/522 | 96.7 | 249/267 | 93.3 | 0.0786 T |

| Yes | 7/140 | 5.0 | 17/522 | 3.3 | 18/267 | 6.7 | ||

| Prior tubal ligation | No | 99/141 | 70.2 | 384/522 | 73.6 | 190/267 | 71.2 | 0.6391 |

| Yes | 42/141 | 29.8 | 138/522 | 26.4 | 77/267 | 28.8 | ||

| Brachytherapy | No | 98/141 | 69.5 | 372/522 | 71.3 | 192/267 | 71.9 | 0.8804 |

| Yes | 43/141 | 30.5 | 150/522 | 28.7 | 75/267 | 28.1 | ||

| External beam radiation therapy | No | 129/141 | 91.5 | 493/522 | 94.4 | 252/267 | 94.4 | 0.4138 |

| Yes | 12/141 | 8.5 | 29/522 | 5.6 | 15/267 | 5.6 | ||

| Chemotherapy | No | 136/141 | 96.5 | 492/522 | 94.3 | 259/267 | 97.0 | 0.1835 |

| Yes | 5/141 | 3.5 | 30/522 | 5.7 | 8/267 | 3.0 | ||

| Uterine Manipulator | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Hohl | V-Care | |||||||

| Variable | Level | n/N | % | n/N | % | n/N | % | p-Value 1 | |

| Recurrence | Total | No | 137/141 | 97.2 | 486/522 | 93.1 | 247/267 | 92.5 | 0.1516 |

| Yes | 4/141 | 2.8 | 36/522 | 6.9 | 20/267 | 7.5 | |||

| Recurrence site | Vaginal | No | 139/141 | 98.6 | 514/522 | 98.5 | 259/267 | 97.0 | 0.3759 |

| Yes | 2/141 | 1.4 | 8/522 | 1.5 | 8/267 | 3.0 | |||

| Peritoneal carcinomatosis | No | 139/141 | 98.6 | 507/522 | 97.1 | 262/267 | 98.1 | 0.5034 | |

| Yes | 2/141 | 1.4 | 15/522 | 2.9 | 5/267 | 1.9 | |||

| Trocart | No | 141/141 | 100 | 518/522 | 99.2 | 266/267 | 99.6 | 0.5806 | |

| Yes | 0/141 | 0.0 | 4/522 | 0.8 | 1/267 | 0.4 | |||

| Pelvic | No | 141/141 | 100 | 513/522 | 98.3 | 264/267 | 98.9 | 0.2899 | |

| Yes | 0/141 | 0.0 | 9/522 | 1.7 | 3/267 | 1.1 | |||

| Distant | No | 140/141 | 99.3 | 510/522 | 97.7 | 263/267 | 98.5 | 0.3872 | |

| Yes | 1/141 | 0.7 | 12/522 | 2.3 | 4/267 | 1.5 | |||

| Disease-specific death | No | 138/141 | 97.9 | 506/522 | 96.9 | 260/267 | 97.4 | 0.8572 | |

| Yes | 3/141 | 2.1 | 16/522 | 3.1 | 7/267 | 2.6 | |||

| Median follow-up (range), months | 48 (3–118) | 60 (16–110) | 48 (3–101) | 57 (3–118) | <0.0001 | ||||

| Analysis of Maximum Likelihood Estimates—Recurrence | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Estimate | Standard Error | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Uterine manipulator | Hohl | 0.40 | 0.55 | 1.491 (0.51–4.40) | 0.4697 |

| V-Care | 0.76 | 0.56 | 2.139 (0.71–6.45) | 0.1769 | |

| FIGO stage | 1B | 1.81 | 1.33 | 6.124 (0.46–82.48) | 0.1720 |

| 2 | −0.24 | 0.97 | 0.787 (0.12–5.31) | 0.8059 | |

| Myometrial infiltration | <50 | 1.02 | 0.40 | 2.779 (1.26–6.12) | 0.0111 * |

| ≥50 | −0.15 | 1.30 | 0.858 (0.07–10.84) | 0.9058 | |

| Histology | Carcinosarcoma | 3.19 | 1.12 | 24.264 (2.72–216.43) | 0.0043 * |

| Clear cell | −11.41 | 712.44 | 0.000 | 0.9872 | |

| Dedifferentiated | 2.33 | 1.54 | 10.304 (0.50–210.78) | 0.1298 | |

| Mixed | 2.28 | 1.145 | 9.825 (1.04–92.85) | 0.0462 * | |

| Serous | 2.67 | 1.11 | 14.413 (1.63–127.18) | 0.0163 * | |

| High-grade (all) | 2.49 | 1.06 | 12.1 (1.52–96.6) | 0.0186 * | |

| Grade | 2 | 0.41 | 0.42 | 1.507 (0.67–3.41) | 0.3238 |

| 3 | −0.24 | 1.09 | 0.786 (0.10–6.59) | 0.8241 | |

| Lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI) | 0.80 | 0.33 | 2.218 (1.16–4.25) | 0.0163 * | |

| Peritoneal washing | 0.34 | 0.55 | 1.399 (0.47–4.12) | 0.5432 | |

| Fallopian tube floaters | 0.28 | 0.42 | 1.321 (0.58–3.02) | 0.5092 | |

| Isolated tumor cells (ITCs) | −1.56 | 1.06 | 0.210 (0.03–1.69) | 0.1419 | |

| Prior tubal ligation | −0.11 | 0.32 | 0.893 (0.48–1.67) | 0.7227 | |

| Brachytherapy | −0.50 | 0.41 | 0.611 (0.27–1.36) | 0.2262 | |

| External beam radiation therapy | 0.13 | 0.61 | 1.143 (0.34–3.810) | 0.8283 | |

| Chemotherapy | −1.24 | 0.53 | 0.291 (0.10–0.82) | 0.0194 * | |

| Analysis of Maximum Likelihood Estimates—Disease-Specific Death | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Estimate | Standard Error | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Uterine manipulator | Hohl | −1.44 | 0.77 | 0.24 (0.05–1.07) | 0.0607 |

| V-Care | −0.80 | 0.78 | 0.45 (0.10–2.06) | 0.3036 | |

| FIGO stage | 1B | 0.37 | 1.74 | 1.44 (0.05–43.60) | 0.8325 |

| 2 | 1.42 | 1.30 | 4.13 (0.32–53.24) | 0.2770 | |

| Myometrial infiltration | <50 | 1.12 | 0.71 | 3.08 (0.76–12.38) | 0.1138 |

| ≥50 | 2.18 | 1.68 | 8.85 (0.33–239.26) | 0.1950 | |

| Histology | Carcinosarcoma | 2.86 | 1.18 | 17.50 (1.74–175.94) | 0.0151 |

| Clear cell | −15.55 | 59 | 0.00 | 0.9979 | |

| Dedifferentiated | 2.76 | 1.67 | 15.75 (0.59–417.47) | 0.0993 | |

| Mixed | 2.23 | 1.24 | 9.33 (0.82–106.34) | 0.0720 | |

| Serous | 2.06 | 1.22 | 7.87 (0.71–86.55) | 0.0919 | |

| High-grade (all) | 2.32 | 1.12 | 10.16 (1.12–92.1) | 0.032 * | |

| Grade | 2 | 0.54 | 0.92 | 1.71 (0.28–10.32) | 0.5571 |

| 3 | 2.30 | 1.22 | 9.95 (0.91–108.73) | 0.0596 | |

| LVSI | 0.92 | 0.53 | 2.51 (0.89–7.04) | 0.0816 | |

| Cytology | −14.88 | 103 | 0.00 | 0.9885 | |

| Fallopian tube floaters | 0.50 | 0.77 | 1.66 (0.36–7.53) | 0.5146 | |

| ITCs | −0.46 | 1.21 | 0.63 (0.06–6.81) | 0.7072 | |

| Prior tubal ligation | 0.61 | 0.50 | 1.85 (0.69–4.95) | 0.2231 | |

| Brachytherapy | −1.14 | 0.59 | 0.32 (0.1–1.02) | 0.0543 | |

| EBRT | −1.06 | 0.95 | 0.35 (0.05–2.22) | 0.2625 | |

| Chemotherapy | −1.28 | 0.69 | 0.28 (0.07–1.06) | 0.0618 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Côté, M.; Renaud, M.-C.; Sebastianelli, A.; Grégoire, J.; Langlais, È.-L.; Singbo, N.; Plante, M. Are Uterine Manipulators Harmful in Minimally Invasive Endometrial Cancer Surgery? A Retrospective Cohort Study. Cancers 2025, 17, 3906. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243906

Côté M, Renaud M-C, Sebastianelli A, Grégoire J, Langlais È-L, Singbo N, Plante M. Are Uterine Manipulators Harmful in Minimally Invasive Endometrial Cancer Surgery? A Retrospective Cohort Study. Cancers. 2025; 17(24):3906. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243906

Chicago/Turabian StyleCôté, Maxime, Marie-Claude Renaud, Alexandra Sebastianelli, Jean Grégoire, Ève-Lyne Langlais, Narcisse Singbo, and Marie Plante. 2025. "Are Uterine Manipulators Harmful in Minimally Invasive Endometrial Cancer Surgery? A Retrospective Cohort Study" Cancers 17, no. 24: 3906. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243906

APA StyleCôté, M., Renaud, M.-C., Sebastianelli, A., Grégoire, J., Langlais, È.-L., Singbo, N., & Plante, M. (2025). Are Uterine Manipulators Harmful in Minimally Invasive Endometrial Cancer Surgery? A Retrospective Cohort Study. Cancers, 17(24), 3906. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243906