High-Dose Transarterial Radioembolization of Hepatic Metastases Using Yttrium-90 Resin Microspheres

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Design

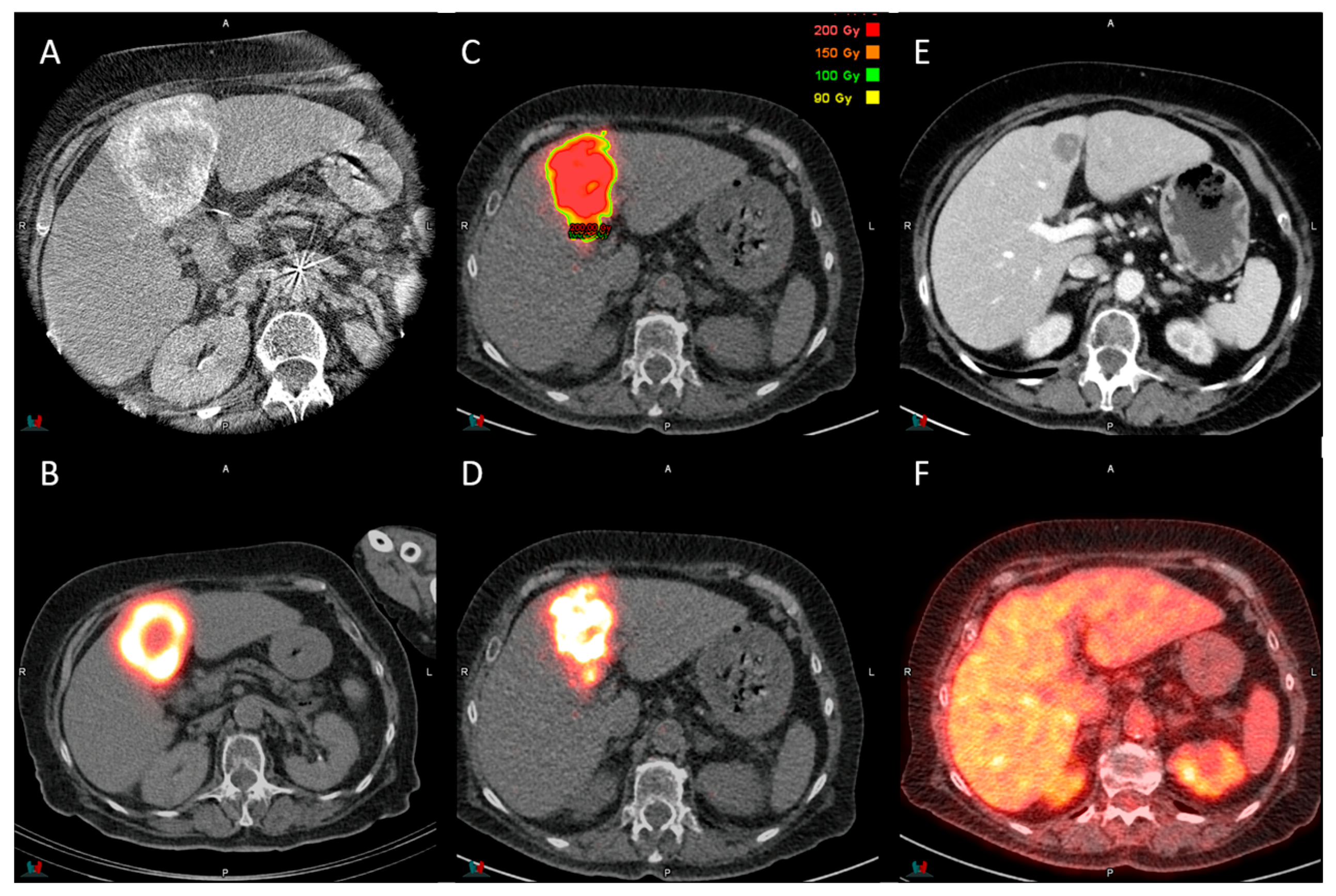

2.2. Procedure and Dosimetry Planning

2.3. Post-Treatment Dosimetry Analysis

2.4. Response and Toxicity Assessment

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographics and Treatment Planning

3.2. Post-Treatment Dosimetry

3.3. Response Assessment

3.4. Toxicity

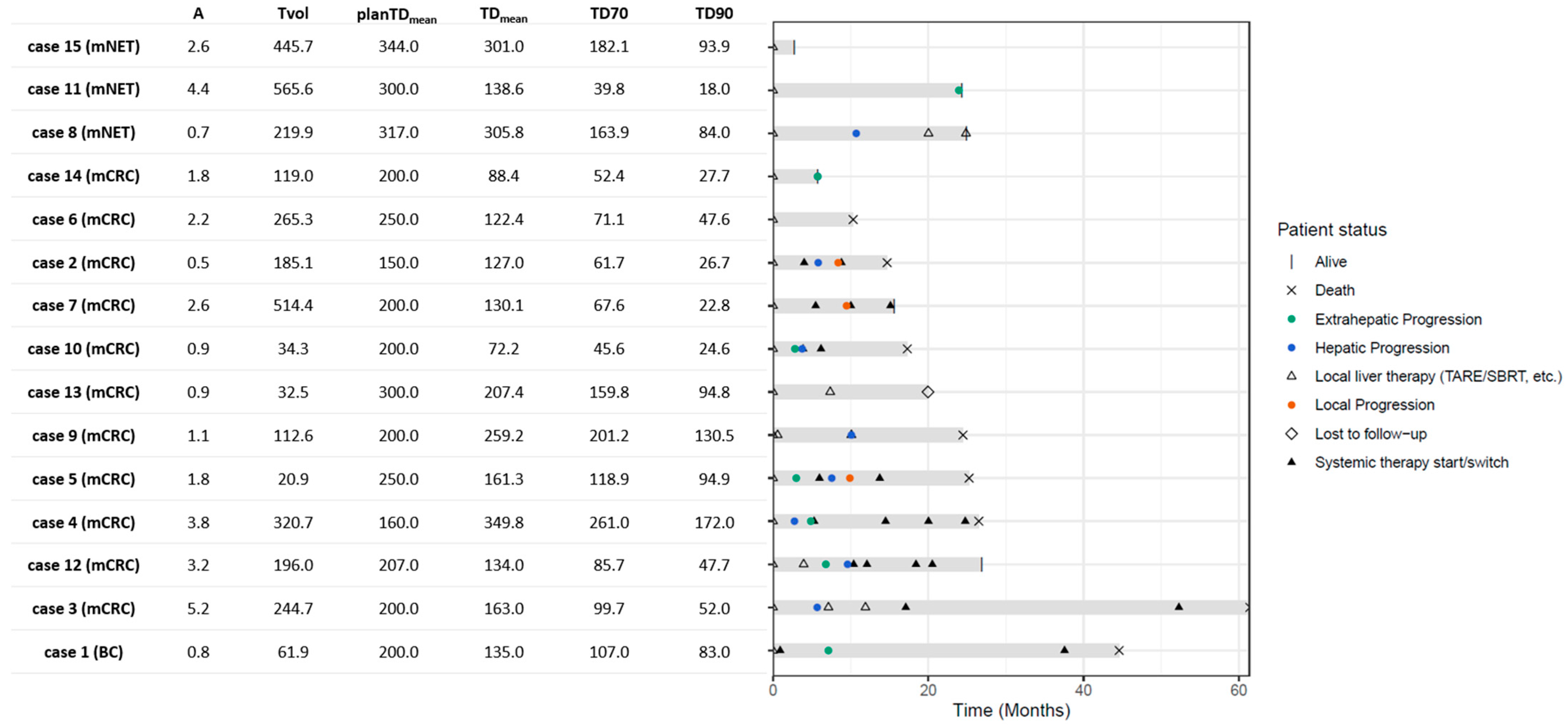

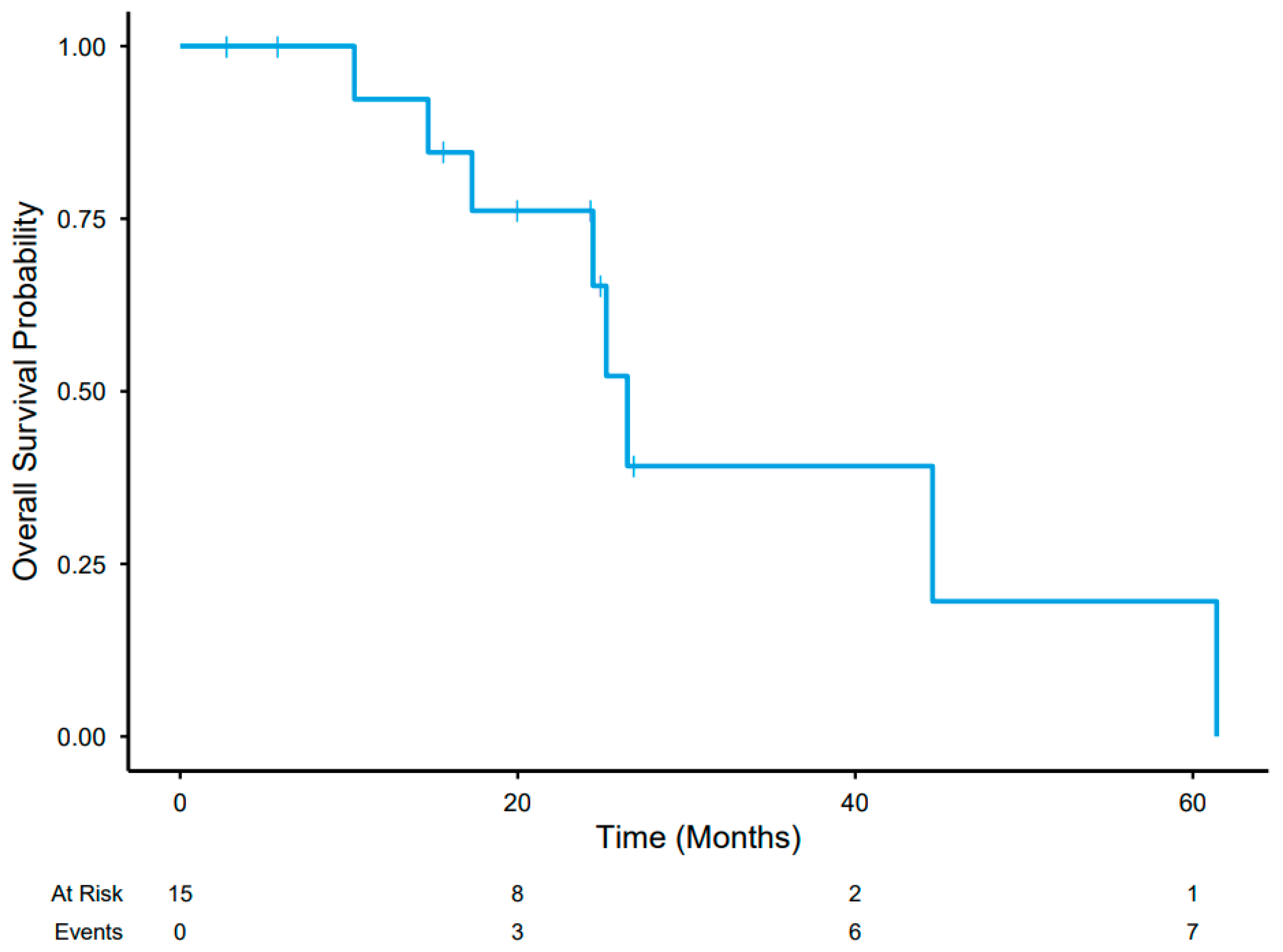

3.5. Post-Treatment Course

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 90Y | Yttrium-90 |

| 99mTc-MAA | 99mTc-labeled Macroaggregated Albumin |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| AUCD30–D90 | The Area Under Curve Calculated from D30 to D90 |

| CE | Contrast Enhanced |

| CEA | Carcinoembryonic Antigen |

| CR | Complete Response |

| CRLM | Colorectal Liver Metastasis |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| CTCAE | Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events |

| D | Dose |

| D70 | The Mean Absorbed Dose in 70% of the Volume |

| D90 | The Mean Absorbed Dose in 90% of the Volume |

| DCR | Disease Control Rate |

| Dmean | Mean Absorbed Dose |

| DVH | Dose–Volume Histogram |

| ECOG | Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group |

| HCC | Hepatocellular Carcinoma |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| MWA | Microwave Ablation |

| ORR | Objective Response Rate |

| OS | Overall Survival |

| PD | Progressive Disease |

| PET | Positron Emission Tomography |

| planTDmean | Planned Mean Tumor Dose |

| PR | Partial Response |

| RECIST | Response Evaluation Criteria for Tumor Response |

| RFA | Radiofrequency Ablation |

| RT | Radiotherapy |

| SBRT | Stereotactic Radiotherapy |

| SD | Stable Disease |

| SPECT | Single-Photon Emission |

| TARE | Trans-Arterial Radioembolization |

| TTP | Time to Progression |

| V | Volume |

| V%<100Gy | The Percentage of Volume That Receives Less Than 100 Gy |

| wTD | Weighted Absorbed Tumor Dose |

References

- Horn, S.R.; Stoltzfus, K.C.; Lehrer, E.J.; Dawson, L.A.; Tchelebi, L.; Gusani, N.J.; Sharma, N.K.; Chen, H.; Trifiletti, D.M.; Zaorsky, N.G. Epidemiology of Liver Metastases. Cancer Epidemiol. 2020, 67, 101760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cutsem, E.; Cervantes, A.; Adam, R.; Sobrero, A.; Van Krieken, J.H.; Aderka, D.; Aranda Aguilar, E.; Bardelli, A.; Benson, A.; Bodoky, G.; et al. ESMO Consensus Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2016, 27, 1386–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, M.; Lam, M.; Chiesa, C.; Konijnenberg, M.; Cremonesi, M.; Flamen, P.; Gnesin, S.; Bodei, L.; Kracmerova, T.; Luster, M.; et al. EANM Procedure Guideline for the Treatment of Liver Cancer and Liver Metastases with Intra-Arterial Radioactive Compounds. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2022, 49, 1682–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2025, 82, 315–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, R.; Johnson, G.E.; Kim, E.; Riaz, A.; Bishay, V.; Boucher, E.; Fowers, K.; Lewandowski, R.; Padia, S.A. Yttrium-90 Radioembolization for the Treatment of Solitary, Unresectable HCC: The LEGACY Study. Hepatology 2021, 74, 2342–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Sher, A.; Abboud, G.; Schwartz, M.; Facciuto, M.; Tabrizian, P.; Knešaurek, K.; Fischman, A.; Patel, R.; Nowakowski, S.; et al. Radiation Segmentectomy for Curative Intent of Unresectable Very Early to Early Stage Hepatocellular Carcinoma (RASER): A Single-Centre, Single-Arm Study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 7, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirtex—DOORwaY90 Study Interim Results. Available online: https://www.sirtex.com/us/products/sir-spheres/clinical-trials/doorway90-study/doorway90-study-interim-results/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Vogel, A.; Chan, S.L.; Dawson, L.A.; Kelley, R.K.; Llovet, J.M.; Meyer, T.; Ricke, J.; Rimassa, L.; Sapisochin, G.; Vilgrain, V.; et al. Hepatocellular Carcinoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Up. Ann. Oncol. 2025, 36, 491–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamarca, A.; Bartsch, D.K.; Caplin, M.; Kos-Kudla, B.; Kjaer, A.; Partelli, S.; Rinke, A.; Janson, E.T.; Thirlwell, C.; van Velthuysen, M.-L.F.; et al. European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS) 2024 Guidance Paper for the Management of Well-Differentiated Small Intestine Neuroendocrine Tumours. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2024, 36, e13423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, A.C.; Savoor, R.; Kircher, S.M.; Kalyan, A.; Benson, A.B.; Hohlastos, E.; Desai, K.R.; Sato, K.; Salem, R.; Lewandowski, R.J. Yttrium-90 Radiation Segmentectomy for Treatment of Neuroendocrine Liver Metastases. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2025, 36, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, A.M.; Savoor, R.; Gordon, A.C.; Riaz, A.; Sato, K.T.; Hohlastos, E.; Salem, R.; Lewandowski, R.J. Yttrium-90 Radiation Segmentectomy in Oligometastatic Secondary Hepatic Malignancies. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2023, 34, 362–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurilova, I.; Bendet, A.; Fung, E.K.; Petre, E.N.; Humm, J.L.; Boas, F.E.; Crane, C.H.; Kemeny, N.; Kingham, T.P.; Cercek, A.; et al. Radiation Segmentectomy of Hepatic Metastases with Y-90 Glass Microspheres. Abdom. Radiol. 2021, 46, 3428–3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padia, S.A.; Johnson, G.E.; Agopian, V.G.; Di Norcia, J.; Srinivasa, R.N.; Sayre, J.; Shin, D.S. Yttrium-90 Radiation Segmentectomy for Hepatic Metastases: A Multi-Institutional Study of Safety and Efficacy. J. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 123, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiers, C.; Taylor, A.; Geller, B.; Toskich, B. Safety and Initial Efficacy of Radiation Segmentectomy for the Treatment of Hepatic Metastases. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2018, 9, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulos, P.M.; Sotirchos, V.S.; Dunne-Jaffe, C.; Petre, E.N.; Gonen, M.; Zhao, K.; Kirov, A.S.; Crane, C.; D’Angelica, M.; Connell, L.C.; et al. Voxel-Based Dosimetry Predicts Local Tumor Progression Post 90 Y Radiation Segmentectomy of Colorectal Liver Metastases. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2025, 50, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entezari, P.; Gabr, A.; Salem, R.; Lewandowski, R.J. Yttrium-90 for Colorectal Liver Metastasis—The Promising Role of Radiation Segmentectomy as an Alternative Local Cure. Int. J. Hyperth. 2022, 39, 620–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soret, M.; Bacharach, S.L.; Buvat, I. Partial-Volume Effect in PET Tumor Imaging. J. Nucl. Med. 2007, 48, 932–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimopoulos, M.-P.; Sotirchos, V.S.; Dunne-Jaffe, C.; Mitchell, A.; Petre, E.N.; Alexander, E.S.; Gonen, M.; Rao, D.; Connell, L.C.; Soares, K.; et al. Tumor Absorbed Dose Predicts Survival and Local Tumor Control in Colorectal Liver Metastases Treated with 90Y Radioembolization. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2025; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paladini, A.; Spinetta, M.; Matheoud, R.; D’Alessio, A.; Sassone, M.; Di Fiore, R.; Coda, C.; Carriero, S.; Biondetti, P.; Laganà, D.; et al. Role of Flex-Dose Delivery Program in Patients Affected by HCC: Advantages in Management of Tare in Our Experience. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, A.W.P.; Mendoza, H.G.; Sellitti, M.J.; Camacho, J.C.; Deipolyi, A.R.; Ziv, E.; Sofocleous, C.T.; Yarmohammadi, H.; Maybody, M.; Humm, J.L.; et al. Optimizing 90Y Particle Density Improves Outcomes After Radioembolization. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2022, 45, 958–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villalobos, A.; Arndt, L.; Cheng, B.; Dabbous, H.; Loya, M.; Majdalany, B.; Bercu, Z.; Kokabi, N. Yttrium-90 Radiation Segmentectomy of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Comparative Study of the Effectiveness, Safety, and Dosimetry of Glass-Based versus Resin-Based Microspheres. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2023, 34, 1226–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Hoven, A.F.; Rosenbaum, C.E.N.M.; Elias, S.G.; de Jong, H.W.A.M.; Koopman, M.; Verkooijen, H.M.; Alavi, A.; van den Bosch, M.A.A.J.; Lam, M.G.E.H. Insights into the Dose-Response Relationship of Radioembolization with Resin 90Y-Microspheres: A Prospective Cohort Study in Patients with Colorectal Cancer Liver Metastases. J. Nucl. Med. 2016, 57, 1014–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadoul, A.; Bernard, C.; Lovinfosse, P.; Gérard, L.; Lilet, H.; Cornet, O.; Hustinx, R. Comparative Dosimetry between 99mTc-MAA SPECT/CT and 90Y PET/CT in Primary and Metastatic Liver Tumors. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2020, 47, 828–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Wei, F.; Yu, H.; Ling, X.; Guo, B.; Shang, J.; Cai, Q.; Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Ran, B.; et al. 99mTc-MAA SPECT/CT Imaging before 90Y-SIRT for Reflecting the Distribution of 90Y Resin Microspheres in Tumors and the Liver: A Comparison with 90Y PET/CT Verification Imaging. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2025, 15, 6272–6286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riveira-Martin, M.; Akhavanallaf, A.; Mansouri, Z.; Bianchetto Wolf, N.; Salimi, Y.; Ricoeur, A.; Mainta, I.; Garibotto, V.; López Medina, A.; Zaidi, H. Predictive Value of 99mTc-MAA-Based Dosimetry in Personalized 90Y-SIRT Planning for Liver Malignancies. EJNMMI Res. 2023, 13, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, M.; Garin, E.; Haste, P.; Denys, A.; Geller, B.; Kappadath, S.C.; Turkmen, C.; Sze, D.Y.; Alsuhaibani, H.S.; Herrmann, K.; et al. Utility of Pre-Procedural [99mTc]TcMAA SPECT/CT Multicompartment Dosimetry for Treatment Planning of 90Y Glass Microspheres in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Comparison of Anatomic versus [99mTc]TcMAA-Based Segmentation. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2024, 52, 744–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, A.; Nasser, I.; Weinstein, J.L.; Odeh, M.; Babar, H.; Dinh, D.; Curry, M.; Bullock, A.; Eckhoff, D.; Dib, M.; et al. Histopathologic Outcomes of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Treated with Transarterial Radioembolization with Yttrium-90 Resin Microspheres. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging, 2025; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleux, G.; Albrecht, T.; Arnold, D.; Bargellini, I.; Cianni, R.; Helmberger, T.; Kolligs, F.; Munneke, G.; Peynircioglu, B.; Sangro, B.; et al. Predictive Factors for Adverse Event Outcomes After Transarterial Radioembolization with Yttrium-90 Resin Microspheres in Europe: Results from the Prospective Observational CIRT Study. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2023, 46, 852–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaefer, N.; Grözinger, G.; Pech, M.; Pfammatter, T.; Soydal, C.; Arnold, D.; Kolligs, F.; Maleux, G.; Munneke, G.; Peynircioglu, B.; et al. Prognostic Factors for Effectiveness Outcomes After Transarterial Radioembolization in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Results from the Multicentre Observational Study CIRT. Clin. Color. Cancer 2022, 21, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zerizer, I.; Al-Nahhas, A.; Towey, D.; Tait, P.; Ariff, B.; Wasan, H.; Hatice, G.; Habib, N.; Barwick, T. The Role of Early 18F-FDG PET/CT in Prediction of Progression-Free Survival after 90Y Radioembolization: Comparison with RECIST and Tumour Density Criteria. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2012, 39, 1391–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 8 (53.3%) |

| Female | 7 (46.6%) | |

| Age | 66 (54.5–71.5) | |

| Primary Tumor Type | Colorectal | 11 (73.3%) |

| Neuroendocrine | 3 (20%) | |

| Breast | 1 (6.7%) | |

| ECOG status | 0 | 9 (60%) |

| 1 | 6 (40%) | |

| Prior Systemic Therapy | 13 (86.7%) | |

| Prior Local Liver Therapy | 7 (47.7%) | |

| Of which n patients had | Bland embolization | 1 (6.7%) |

| Radioembolization | 2 (13.3%) | |

| Surgical resection | 3 (20%) | |

| Chip and burn | 3 (20%) | |

| Ablation (RFA/MWA) | 3 (20%) | |

| Stereotactic Body RT (SBRT) | 2 (13.3%) | |

| Intra-arterial pump chemotherapy | 1 (6.7%) | |

| Extra-hepatic disease at baseline | 7 (46.7%) | |

| Of which n patients had | Lung | 6 (40%) |

| Lymph node | 4 (26.7%) | |

| Bone | 1 (6.67%) | |

| Soft tissue | 1 (6.67%) | |

| Tumor burden (%) 1 | 10.0 (4.7–14.2) | |

| Treatment strategy | Segmental | 6 (40%) |

| Unilobar | 5 (33.3%) | |

| Bilobar | 4 (26.7%) | |

| Baseline lab | Bilirubin, total serum (µmol/L) | 6 (6–9) |

| Aspartate transaminase (U/L) | 28 (24–34) | |

| Alanine transaminase (U/L | 22 (19–28.5) | |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (U/L) | 128 (86.5–201) | |

| Gamma-glutamyl Transferase (U/L) | 98 (48.5–144.5) | |

| Median follow-up time | 25.2 (17.3–26.9) |

| Radiological Response | 3 Months Post TARE | Best Response |

|---|---|---|

| Complete Response | 0 | 0 |

| Partial Response | 10 (66.7%) | 12 (80%) |

| Stable Disease | 5 (33.3%) | 3 (20%) |

| Progressive Disease | 0 | 0 |

| Disease Control Rate | 15 (100%) | 15 (100%) |

| CTCAE Grade | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Terminology | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Abdominal Pain | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Anemia | 5 | 1 | 0 |

| Fatigue | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| Fever | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Nausea | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| ↑ Alanine Aminotransferase | 5 | 1 | 0 |

| ↑ Alkaline Phosphatase | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| ↑ Aspartate Aminotransferase | 9 | 1 | 0 |

| ↑ Blood Bilirubin | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| ↑ Blood Lactate Dehydrogenase | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| ↑ GGT | 1 | 5 | 1 |

| Hypophosphatemia | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| ↓ Lymphocyte Count | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| ↓ Platelet Count | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| ↓ White Blood Cell Count | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 49 | 16 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schneider, C.C.I.; de Wit-van der Veen, B.J.; Jansen, S.M.A.; Hergaarden, K.F.M.; Tesselaar, M.E.T.; Kok, N.F.M.; van Golen, L.W.; Braat, A.J.A.T.; Beets-Tan, R.G.H.; Baetens, T.R.; et al. High-Dose Transarterial Radioembolization of Hepatic Metastases Using Yttrium-90 Resin Microspheres. Cancers 2025, 17, 3889. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243889

Schneider CCI, de Wit-van der Veen BJ, Jansen SMA, Hergaarden KFM, Tesselaar MET, Kok NFM, van Golen LW, Braat AJAT, Beets-Tan RGH, Baetens TR, et al. High-Dose Transarterial Radioembolization of Hepatic Metastases Using Yttrium-90 Resin Microspheres. Cancers. 2025; 17(24):3889. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243889

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchneider, Charlotte C. I., Belinda J. de Wit-van der Veen, Sanne M. A. Jansen, Kenneth F. M. Hergaarden, Margot E. T. Tesselaar, Niels F. M. Kok, Larissa W. van Golen, Arthur J. A. T. Braat, Regina G. H. Beets-Tan, Tarik R. Baetens, and et al. 2025. "High-Dose Transarterial Radioembolization of Hepatic Metastases Using Yttrium-90 Resin Microspheres" Cancers 17, no. 24: 3889. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243889

APA StyleSchneider, C. C. I., de Wit-van der Veen, B. J., Jansen, S. M. A., Hergaarden, K. F. M., Tesselaar, M. E. T., Kok, N. F. M., van Golen, L. W., Braat, A. J. A. T., Beets-Tan, R. G. H., Baetens, T. R., & Klompenhouwer, E. G. (2025). High-Dose Transarterial Radioembolization of Hepatic Metastases Using Yttrium-90 Resin Microspheres. Cancers, 17(24), 3889. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243889