Emerging Role of Transcutaneous Ultrasound in the Diagnostic of Lung Cancer

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

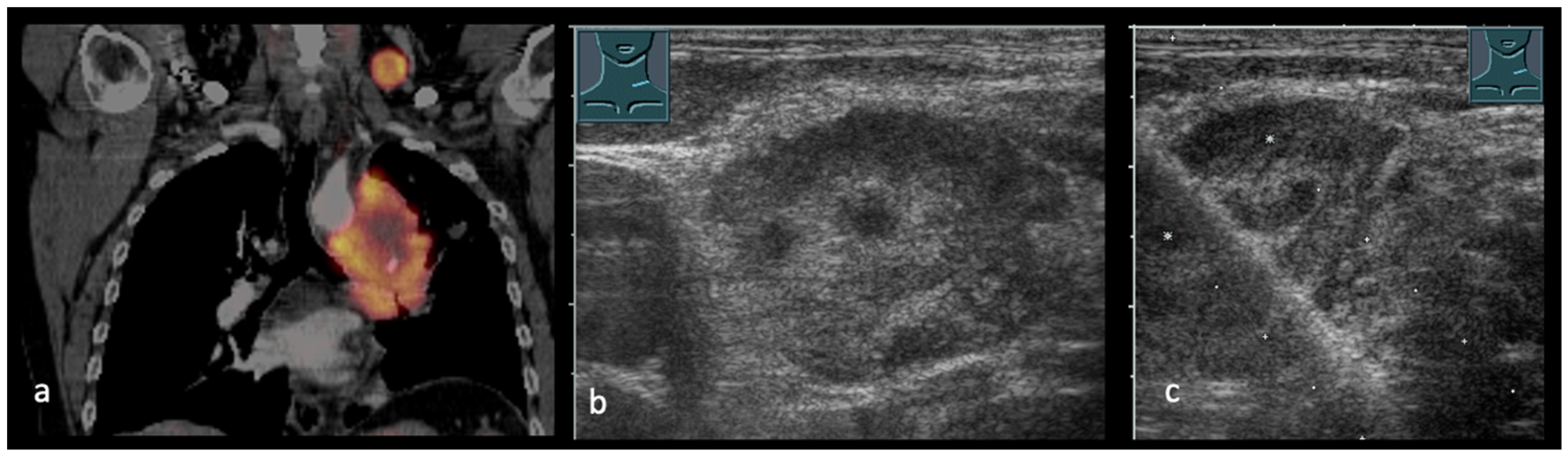

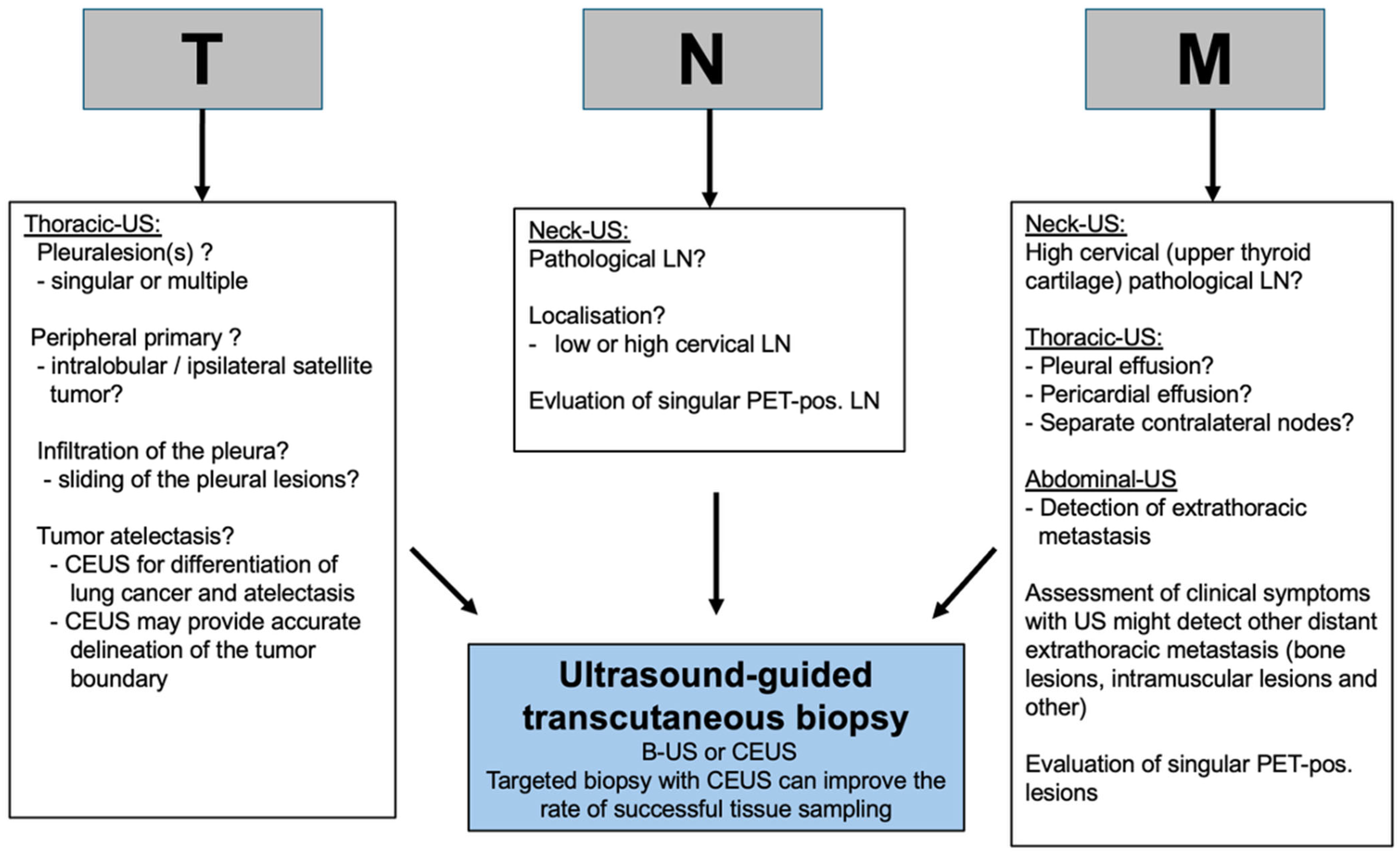

2. Transcutaneous Ultrasound in the Primary Staging of Lung Cancer

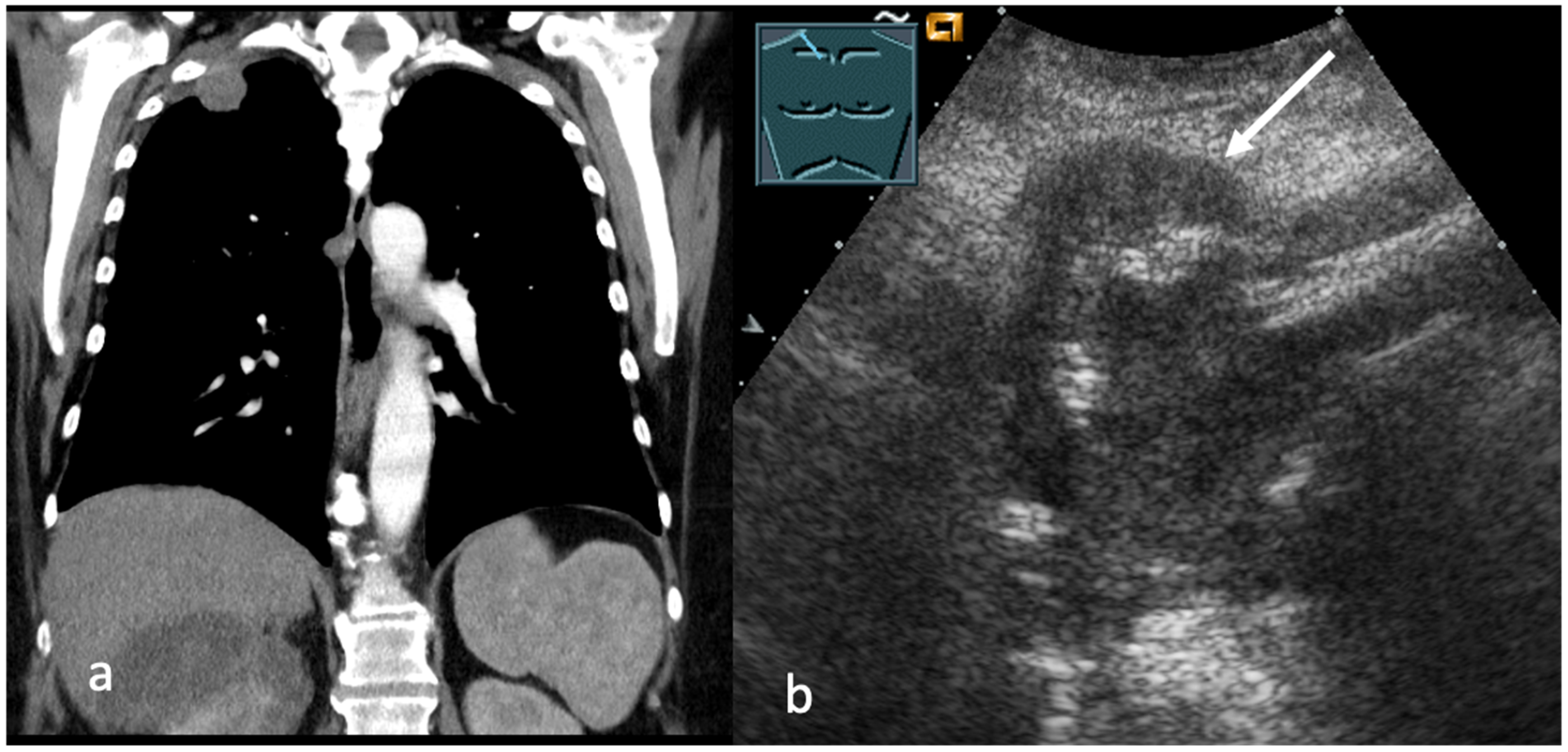

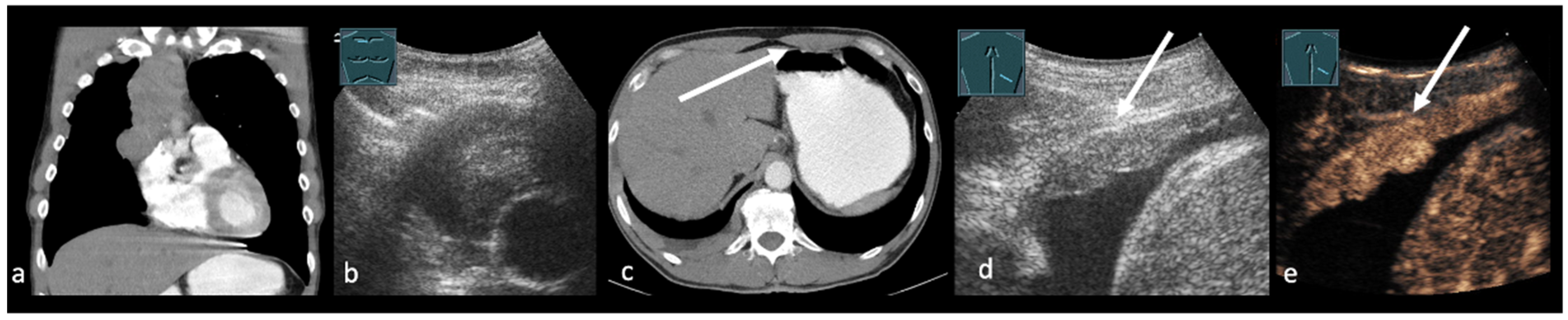

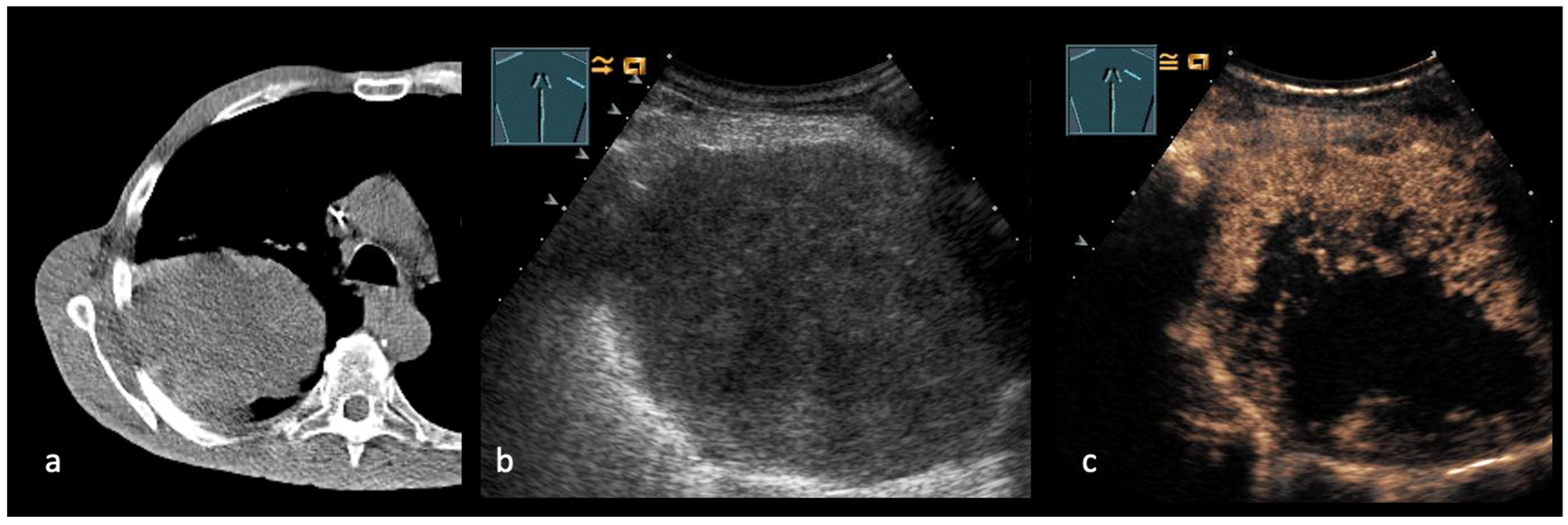

3. Transthoracic Ultrasound in the Evaluation and Characterizing of Local Tumor Size (T-Stage)

4. Transcutaneous Ultrasound in the Evaluation of Supraclavicular and Collar Lymph Nodes

5. Transcutaneous Ultrasound in the Evaluation Distant Metastasis

6. Ultrasound Guided Biopsy

7. Discussion

8. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft DKA. Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, AWMF): Prävention, Diagnostik, Therapie und Nachsorge des Lungenkarzinoms, Lang-version 4.0. 2025. AWMF-Registernummer: 020-007OL. Available online: https://www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Downloads/Leitlinien/Lungenkarzinom/Version_4/LL_Lungenkarzinom_Langversion_4.0.pdf/ (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Molina, J.R.; Yang, P.; Cassivi, S.D.; Schild, S.E.; Adjei, A.A. Non-small cell lung cancer: Epidemiology, risk factors, treatment, and survivorship. Mayo. Clin. Proc. 2008, 83, 584–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassanein, S.S.; Abdel-Mawgood, A.L.; Ibrahim, S.A. EGFR-Dependent Extracellular Matrix Protein Interactions Might Light a Candle in Cell Behavior of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 766659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trenker, C.; Schröder, W.; Görg, C.; Schuler, A. Bedeutung des Ultraschalls in der Ausbreitungsdiagnostik des Bronchialkarzinoms, Importance of ultrasound in the staging of bronchial carcinoma. Atemwegs-Lungenkrankh. 2022, 48, 378–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraywinkel, K.B.B. Epidemiologie des kleinzelligen Lungenkarzinoms in Deutschland. Onkologe 2017, 23, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraywinkel, K.S.I. Epidemiologie des nichtkleinzelligen Lungenkarzinoms in Deutschland. Onkologe 2018, 24, 946–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sholl, L. Molecular diagnostics of lung cancer in the clinic. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2017, 6, 560–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocher, F.; Hilbe, W.; Seeber, A.; Pircher, A.; Schmid, T.; Greil, R.; Auberger, J.; Nevinny-Stickel, M.; Sterlacci, W.; Tzankov, A.; et al. Longitudinal analysis of 2293 NSCLC patients: A comprehensive study from the TYROL registry. Lung Cancer 2015, 87, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingemans, A.-M.C.; Früh, M.; Ardizzoni, A.; Besse, B.; Faivre-Finn, C.; Hendriks, L.E.; Lantuejoul, S.; Peters, S.; Reguart, N.; Rudin, C.M.; et al. Small-cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 839–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planchard, D.; Popat, S.; Kerr, K.; Novello, S.; Smit, E.F.; Faivre-Finn, C.; Mok, T.S.; Reck, M.; Van Schil, P.E.; Hellmann, M.D.; et al. Metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29 (Suppl. S4), iv192–iv237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, D.; Shah, A.B.; Dela, J.R.C.; Mugibel, T.A.; Sumaily, K.M.; Sabi, E.M.; Mujamammi, A.H.; Malafi, M.E.; Alkaff, S.A.; Alwahbi, T.A.; et al. Lung Ultrasonography Accuracy for Diagnosis of Adult Pneumonia: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adv. Respir. Med. 2024, 92, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez, M.A.; Shams, N.; Ellington, L.E.; Naithani, N.; Gilman, R.H.; Steinhoff, M.C.; Santosham, M.; Black, R.E.; Price, C.; Gross, M.; et al. Lung ultrasound for the diagnosis of pneumonia in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir. Res. 2014, 15, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpicelli, G. Sonographic diagnosis of pneumothorax. Intensive Care Med. 2011, 37, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathis, G.; Blank, W.; Reissig, A.; Lechleitner, P.; Reuss, J.; Schuler, A.; Beckh, S. Thoracic ultrasound for diagnosing pulmonary embolism: A prospective multicenter study of 352 patients. Chest 2005, 128, 1531–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, A.L.; Gleeson, F.V. Radiology in pleural disease: State of the art. Respirology 2004, 9, 300–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekiya, M. Chest ultrasound for lung cancer: Present and future. J. Med. Ultrason 2024, 51, 393–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakao, M.; Yoshida, J.; Ishii, G.; Kawase, A.; Maeda, R.; Aokage, K.; Hishida, T.; Nishimura, M.; Nagai, K. Prognostic impact of node involvement pattern in pN1 non-small cell lung cancer patients. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2010, 5, 1576–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daly, M.E.; Singh, N.; Ismaila, N.; Antonoff, M.B.; Arenberg, D.A.; Bradley, J.; David, E.; Detterbeck, F.; Früh, M.; Gubens, M.A.; et al. Management of Stage III Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: ASCO Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 1356–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remon, J.; Soria, J.-C.; Peters, S.; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Early and locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: An update of the ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines focusing on diagnosis, staging, systemic and local therapy. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 1637–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, R.; Görg, C.; Prosch, H.; Safai Zadeh, E.; Jenssen, C.; Dietrich, C.F. Sonography of the pleura. Ultraschall Med. 2024, 45, 118–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruffini, E.; Huang, J.; Cilento, V.; Goren, E.; Detterbeck, F.; Ahmad, U.; Appel, S.; Bille, A.; Boubia, S.; Brambilla, C.; et al. The International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Thymic Epithelial Tumors Staging Project: Proposal for a Stage Classification for the Forthcoming (Ninth) Edition of the TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2023, 18, 1655–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facciolo, F.; Cardillo, G.; Lopergolo, M.; Pallone, G.; Sera, F.; Martelli, M. Chest wall invasion in non-small cell lung carcinoma: A rationale for en bloc resection. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2001, 121, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, N.; Saitoh, T.; Kitamura, S. Tumor invasion of the chest wall in lung cancer: Diagnosis with US. Radiology 1993, 187, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caroli, G.; Dell’Amore, A.; Cassanelli, N.; Dolci, G.; Pipitone, E.; Asadi, N.; Stella, F.; Bini, A. Accuracy of transthoracic ultrasound for the prediction of chest wall infiltration by lung cancer and of lung infiltration by chest wall tumours. Heart Lung Circ. 2015, 24, 1020–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandi, V.; Lunn, W.; Ernst, A.; Eberhardt, R.; Hoffmann, H.; Herth, F.J.F. Ultrasound vs. CT in detecting chest wall invasion by tumor: A prospective study. Chest 2008, 133, 881–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanuti, M. Surgical Management of Lung Cancer Involving the Chest Wall. Thorac. Surg. Clin. 2017, 27, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prosch, H.; Mathis, G.; Mostbeck, G.H. Percutaneous ultrasound in diagnosis and staging of lung cancer. Ultraschall Med. 2008, 29, 466–478. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loi, M.; Mazzella, A.; Desideri, I.; Fournel, L.; Hamelin, E.C.; Icard, P.; Bobbio, A.; Alifano, M. Chest wall resection and reconstruction for lung cancer: Surgical techniques and example of integrated multimodality approach. J. Thorac. Dis. 2020, 12, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findeisen, H.; Trenker, C.; Figiel, J.; Greene, B.H.; Görg, K.; Görg, C. Vascularization of Primary, Peripheral Lung Carcinoma in CEUS—A Retrospective Study (n = 89 Patients). Ultraschall Med. 2019, 40, 603–608. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safai Zadeh, E.; Huber, K.P.; Görg, C.; Prosch, H.; Findeisen, H. The Value of Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound (CEUS) in the Evaluation of Central Lung Cancer with Obstructive Atelectasis. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafez, M.R.; Sobh, E.S.; Elsawy, S.B.; Abo-Elkheir, O.I. The usefulness of thoracic ultrasonography in diagnosis and staging of bronchogenic carcinoma. Ultrasound 2017, 25, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusch, V.W.; Asamura, H.; Watanabe, H.; Giroux, D.J.; Rami-Porta, R.; Goldstraw, P. Members of IASLC Staging Committee The IASLC lung cancer staging project: A proposal for a new international lymph node map in the forthcoming seventh edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2009, 4, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leicher-Düber, V.A.; Bleier, R.; Düber, C.; Thelen, M. Halslymphknotenmetastasen: Histologisch Kontrollierter Vergleich von Palpation, Sonographie und Computertomographie [Cervical Lymph Node Metastases: A Histologically Controlled Comparison of Palpation, Sonography and Computed Tomography]. In RöFo-Fortschritte auf Dem Gebiet der Röntgenstrahlen und der Bildgebenden Verfahren; Georg Thieme Verlag Stuttgart: Stuttgart, Germany, 1990; Volume 153, pp. 575–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Vliet, E.P.M.; van der Lugt, A.; Kuipers, E.J.; Tilanus, H.W.; van der Gaast, A.; Hermans, J.J.; Siersema, P.D. Ultrasound, computed tomography, or the combination for the detection of supraclavicular lymph nodes in patients with esophageal or gastric cardia cancer: A comparative study. J. Surg. Oncol. 2007, 96, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prosch, H.; Strasser, G.; Sonka, C.; Oschatz, E.; Mashaal, S.; Mohn-Staudner, A.; Mostbeck, G.H. Cervical ultrasound (US) and US-guided lymph node biopsy as a routine procedure for staging of lung cancer. Ultraschall Med. 2007, 28, 598–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilakopoulos, T.P.; Pangalis, G.A. Application of a prediction rule to select which patients presenting with lymphadenopathy should undergo a lymph node biopsy. Medicine 2000, 79, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.; Qiu, B.-M.; Luo, J.; Diao, Y.-F.; Hu, L.-W.; Liu, X.-L.; Shen, Y. Distant metastasis patterns among lung cancer subtypes and impact of primary tumor resection on survival in metastatic lung cancer using SEER database. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Tang, W.; Jin, F.; Luo, H.; Yang, H.; Wang, Y. Comprehensive Analysis of Lung Cancer Metastasis: Sites, Rates, Survival, and Risk Factors-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Respir. J. 2025, 19, e70107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefifard, M.; Baikpour, M.; Ghelichkhani, P.; Asady, H.; Shahsavari Nia, K.; Moghadas Jafari, A.; Hosseini, M.; Safari, S. Screening Performance Characteristic of Ultrasonography and Radiography in Detection of Pleural Effusion; a Meta-Analysis. Emergency 2016, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Mathis, G. Use of lung and pleural ultrasonography in emergency and intensive care medicine. Med. Klin. Intensivmed. Notfmed. 2019, 114, 504–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.C.; Luh, K.T.; Chang, D.B.; Wu, H.D.; Yu, C.J.; Kuo, S.H. Value of sonography in determining the nature of pleural effusion: Analysis of 320 cases. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 1992, 159, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safai Zadeh, E.; Weide, J.; Dietrich, C.F.; Trenker, C.; Koczulla, A.R.; Görg, C. Diagnostic Accuracy of B-Mode- and Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound in Differentiating Malignant from Benign Pleural Effusions. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findeisen, H.; Görg, C.; Hartbrich, R.; Dietrich, C.F.; Görg, K.; Trenker, C.; Safai Zadeh, E. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound is helpful for differentiating benign from malignant parietal pleural lesions. J. Clin. Ultrasound 2022, 50, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trenker, C.; Görg, C.; Jenssen, C.; Klein, S.; Neubauer, A.; Wagner, U.; Dietrich, C.F. Ultrasound in oncology, current perspectives. Z Gastroenterol. 2017, 55, 1021–1037. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kinkel, K.; Lu, Y.; Both, M.; Warren, R.S.; Thoeni, R.F. Detection of hepatic metastases from cancers of the gastrointestinal tract by using noninvasive imaging methods (US, CT, MR imaging, PET): A meta-analysis. Radiology 2002, 224, 748–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudon, M.; Dietrich, C.F.; Choi, B.I.; Cosgrove, D.O.; Kudo, M.; Nolsøe, C.P.; Piscaglia, F.; Wilson, S.R.; Barr, R.G.; Chammas, M.C.; et al. Guidelines and good clinical practice recommendations for Contrast Enhanced Ultrasound (CEUS) in the liver—update 2012: A WFUMB-EFSUMB initiative in cooperation with representatives of AFSUMB, AIUM, ASUM, FLAUS and ICUS. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2013, 39, 187–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernatik, T.; Seitz, K.; Blank, W.; Schuler, A.; Dietrich, C.F.; Strobel, D. Unclear focal liver lesions in contrast-enhanced ultrasonography--lessons to be learned from the DEGUM multicenter study for the characterization of liver tumors. Ultraschall Med. 2010, 31, 577–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernatik, T.; Schuler, A.; Kunze, G.; Mauch, M.; Dietrich, C.F.; Dirks, K.; Pachmann, C.; Börner, N.; Fellermann, K.; Menzel, J.; et al. Benefit of Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound (CEUS) in the Follow-Up Care of Patients with Colon Cancer: A Prospective Multicenter Study. Ultraschall Med. 2015, 36, 590–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich-Rust, M.; Klopffleisch, T.; Nierhoff, J.; Herrmann, E.; Vermehren, J.; Schneider, M.D.; Zeuzem, S.; Bojunga, J. Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound for the differentiation of benign and malignant focal liver lesions: A meta-analysis. Liver Int. 2013, 33, 739–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, C.F.; Nolsøe, C.P.; Barr, R.G.; Berzigotti, A.; Burns, P.N.; Cantisani, V.; Chammas, M.C.; Chaubal, N.; Choi, B.I.; Clevert, D.A.; et al. Guidelines and Good Clinical Practice Recommendations for Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound (CEUS) in the Liver-Update 2020 WFUMB in Cooperation with EFSUMB, AFSUMB, AIUM, and FLAUS. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2020, 46, 2579–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.J.; Chan, H.P.; Soon, Y.Y.; Huang, Y.; Soo, R.A.; Kee, A.C.L. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the adequacy of endobronchial ultrasound transbronchial needle aspiration for next-generation sequencing in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2022, 166, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Park, B.K.; Kim, C.K. Sonographically guided transhepatic core biopsies of right renal and adrenal masses: Safety and short-term follow-up. J. Ultrasound Med. 2013, 32, 2013–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorentzen, T.; Nolsøe, C.P.; Ewertsen, C.; Nielsen, M.B.; Leen, E.; Havre, R.F.; Gritzmann, N.; Brkljacic, B.; Nürnberg, D.; Kabaalioğlu, A.; et al. EFSUMB EFSUMB Guidelines on Interventional Ultrasound (INVUS), Part I. General Aspects (Short Version); Georg Thieme Verlag KG: Stuttgart, Germany, 2015; Volume 36, pp. 464–472. [Google Scholar]

- Argon Medical Devices. BioPince™ Full Core Biopsy Instrument. Argon Medical Devices Website. Available online: https://www.argonmedical.com/product/biopince-full-core-biopsy-instrument/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Diederich, S.; Padge, B.; Vossas, U.; Hake, R.; Eidt, S. Application of a single needle type for all image-guided biopsies: Results of 100 consecutive core biopsies in various organs using a novel tri-axial, end-cut needle. Cancer Imaging 2006, 6, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzidei, M.; Porfiri, A.; Andrani, F.; Di Martino, M.; Saba, L.; Catalano, C.; Bezzi, M. Imaging-guided chest biopsies: Techniques and clinical results. Insights Imaging 2017, 8, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oikonomou, A.; Matzinger, F.R.; Seely, J.M.; Dennie, C.J.; Macleod, P.J. Ultrathin needle (25 G) aspiration lung biopsy: Diagnostic accuracy and complication rates. Eur. Radiol. 2004, 14, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yu, L.-L.; Li, L.; Tang, X.-M.; He, P.; Gu, P. Ultrasound-guided core-needle biopsy for peripheral pulmonary lesions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Radiol. 2023, 78, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, N.; Watanabe, T.; Yamada, K.; Nakai, T.; Suzumura, T.; Sakagami, K.; Yoshimoto, N.; Sato, K.; Tanaka, H.; Mitsuoka, S.; et al. Efficacy and safety of ultrasound (US) guided percutaneous needle biopsy for peripheral lung or pleural lesion: Comparison with computed tomography (CT) guided needle biopsy. J. Thorac. Dis. 2019, 11, 936–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiBardino, D.M.; Yarmus, L.B.; Semaan, R.W. Transthoracic needle biopsy of the lung. J. Thorac. Dis. 2015, 7, S304–S316. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wilczynski, A.; Görg, C.; Timmesfeld, N.; Ramaswamy, A.; Neubauer, A.; Burchert, A.; Trenker, C. Value and Diagnostic Accuracy of Ultrasound-Guided Full Core Needle Biopsy in the Diagnosis of Lymphadenopathy: A Retrospective Evaluation of 793 Cases. J. Ultrasound Med. 2020, 39, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobel, D.; Bernatik, T.; Blank, W.; Will, U.; Reichel, A.; Wüstner, M.; Keim, V.; Schacherer, D.; Barreiros, A.P.; Kunze, G.; et al. Incidence of bleeding in 8172 percutaneous ultrasound-guided intraabdominal diagnostic and therapeutic interventions—Results of the prospective multicenter DEGUM interventional ultrasound study (PIUS study). Ultraschall Med. 2015, 36, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Wang, D.; Li, H.; Zhao, S.; Chen, M.; Li, H.; Ding, Z.; Liu, J.; Liu, L. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound for needle biopsy of thoracic lesions. Oncol. Lett. 2020, 20, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López González, F.J.; García Alfonso, L.; Cascón Hernández, J.; Ariza Prota, M.; Herrero Huertas, J.; Hermida Valverde, T.; Ruíz Álvarez, I.; Torres Rivas, H.E.; Fernández Fernández, L.M.; Enríquez Rodríguez, A.I.; et al. Biopsy of Intrapulmonary Lesions in Lungs with Atelectasis and Pleural Effusion. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2021, 57, 438–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Lou, J.; Bao, L.; Lv, Z. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound for needle biopsy of central lung cancer with atelectasis. J. Med. Ultrason 2018, 45, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, P.C.; Lee, L.N.; Luh, K.T.; Kuo, S.H.; Yang, S.P. Ultrasonography of Pancoast tumor. Chest 1988, 94, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginsberg, R.J.; Martini, N.; Zaman, M.; Armstrong, J.G.; Bains, M.S.; Burt, M.E.; McCormack, P.M.; Rusch, V.W.; Harrison, L.B. Influence of surgical resection and brachythe- rapy in the management of superior sulcus tumor. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1994, 57, 1440–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoetzenecker, K.; Klepetko, W. Pancoast Tumore. Interdiszip. Onkol. 2013, 5, 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Paulson, D.L.; Weed, T.E.; Rian, R.L. Cervical approach for percutaneous needle biopsy of Pancoast tumors. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1985, 39, 586–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, W.J.; Thornbury, J.R.; Naylor, B. Pulmonary needle aspiration biopsy in the diagnosis of Pancoast tumors. Radiology 1974, 111, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagopoulos, N.; Leivaditis, V.; Koletsis, E.; Prokakis, C.; Alexopoulos, P.; Baltayiannis, N.; Hatzimichalis, A.; Tsakiridis, K.; Zarogoulidis, P.; Zarogoulidis, K.; et al. Pancoast tumors: Characteristics and preoperative assessment. J. Thorac. Dis. 2014, 6 (Suppl. S1), S108–S115. [Google Scholar]

- Ekiz, T.; Kermenli, T.; Pazarlı, A.C.; Akarsu, E.; Yalçınöz, K. Ultrasonographic Imaging of a Pancoast Tumor Presenting with Breakthrough Pain and Not Visualized by Plane Radiograph. Pain. Med. 2016, 17, 2437–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpi, S.; Ali, J.M.; Tasker, A.; Peryt, A.; Aresu, G.; Coonar, A.S. The role of positron emission tomography in the diagnosis, staging and response assessment of non-small cell lung cancer. Ann. Transl. Med. 2018, 6, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, W.; Kong, F.; Sun, X.; Zuo, X. Meta-analysis: Accuracy of 18FDG PET-CT for distant metastasis staging in lung cancer patients. Surg. Oncol. 2013, 22, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lardinois, D.; Weder, W.; Roudas, M.; von Schulthess, G.K.; Tutic, M.; Moch, H.; Stahel, R.A.; Steinert, H.C. Etiology of solitary extrapulmonary positron emission tomography and computed tomography findings in patients with lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 6846–6853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, M.; Patel, D.; Viars, M.; Tsintolas, J.; Peksa, G.D.; Bailitz, J. Comparison of artificial intelligence versus real-time physician assessment of pulmonary edema with lung ultrasound. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2023, 70, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, Y.; Kaneko, T.; Yoshikawa, H.; Uchiyama, S.; Nagata, Y.; Matsushita, Y.; Hiki, M.; Minamino, T.; Takahashi, K.; Daida, H.; et al. Artificial intelligence-based point-of-care lung ultrasound for screening COVID-19 pneumoniae: Comparison with CT scans. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0281127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Macruz, F.; Wu, D.; Bridge, C.; McKinney, S.; Al Saud, A.A.; Sharaf, E.; Sesic, I.; Pely, A.; Danset, P.; et al. Point-of-care AI-assisted stepwise ultrasound pneumothorax diagnosis. Phys. Med. Biol. 2023, 68, 205013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Ultrasound in the Diagnostic of Lung Cancer | |

|---|---|

| AWMF |

|

| ESMO |

|

| ASCO |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Trenker-Burchert, C.; Dohse, M.; Findeisen, H.; Schuler, A.; Görg, C. Emerging Role of Transcutaneous Ultrasound in the Diagnostic of Lung Cancer. Cancers 2025, 17, 3873. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233873

Trenker-Burchert C, Dohse M, Findeisen H, Schuler A, Görg C. Emerging Role of Transcutaneous Ultrasound in the Diagnostic of Lung Cancer. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3873. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233873

Chicago/Turabian StyleTrenker-Burchert, Corinna, Marius Dohse, Hajo Findeisen, Andreas Schuler, and Christian Görg. 2025. "Emerging Role of Transcutaneous Ultrasound in the Diagnostic of Lung Cancer" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3873. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233873

APA StyleTrenker-Burchert, C., Dohse, M., Findeisen, H., Schuler, A., & Görg, C. (2025). Emerging Role of Transcutaneous Ultrasound in the Diagnostic of Lung Cancer. Cancers, 17(23), 3873. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233873