Pleural Mesothelioma Diagnosis for the Pulmonologist: Steps Along the Way

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Rationale

1.2. Aims and Scope of the Review

2. Methodology of the Review

3. Epidemiology, Etiology and Pathogenesis

3.1. Occupational and Environmental Risk Factors

3.2. Pathogenesis and Disease Progression

4. Clinical Presentation and Initial Assessment

4.1. Symptoms and Signs

4.2. Differential Diagnosis

4.3. Role of the Pulmonologist in Early Evaluation

5. Imaging Modalities in the Diagnostic Pathway

5.1. Chest Radiography

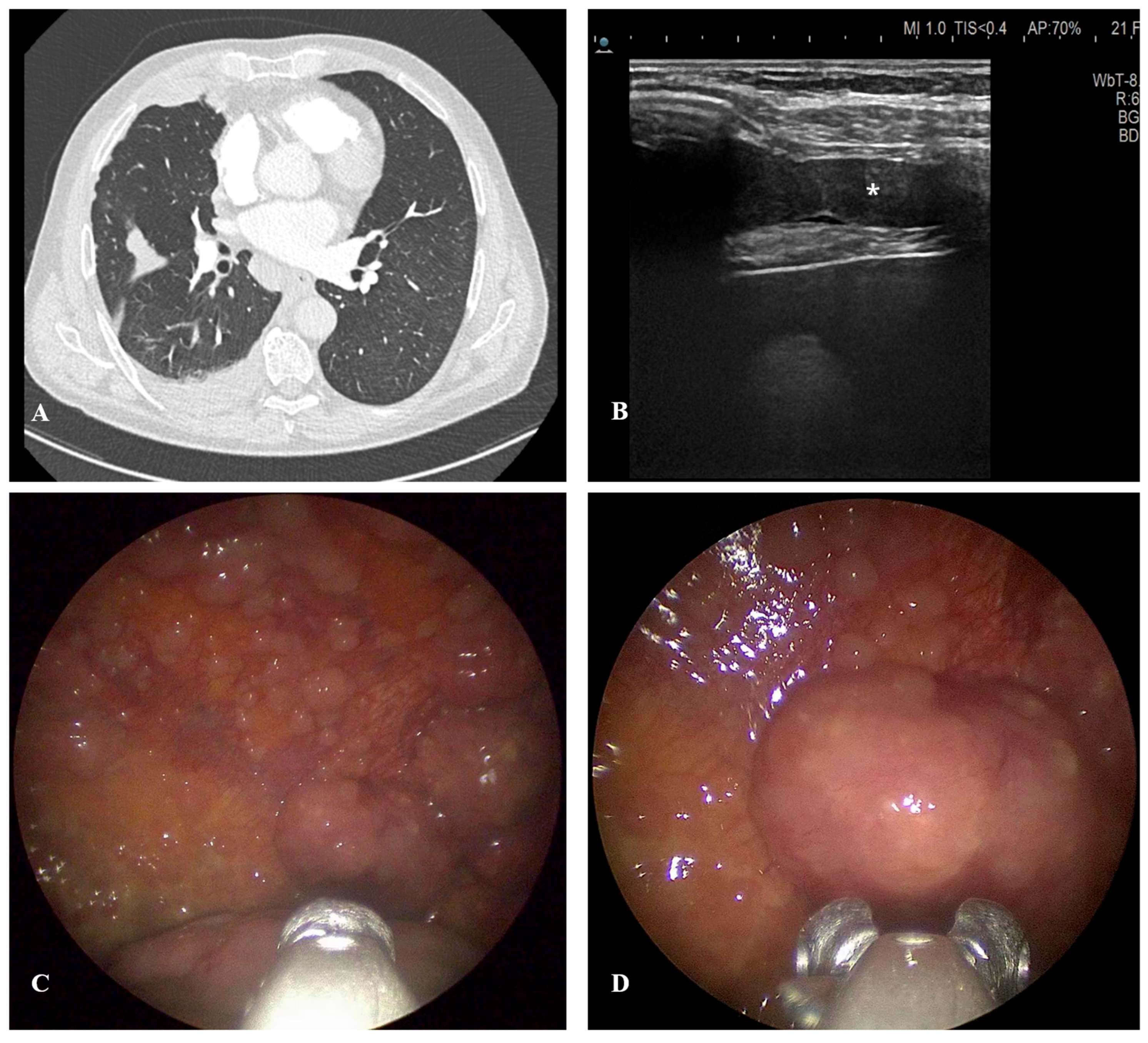

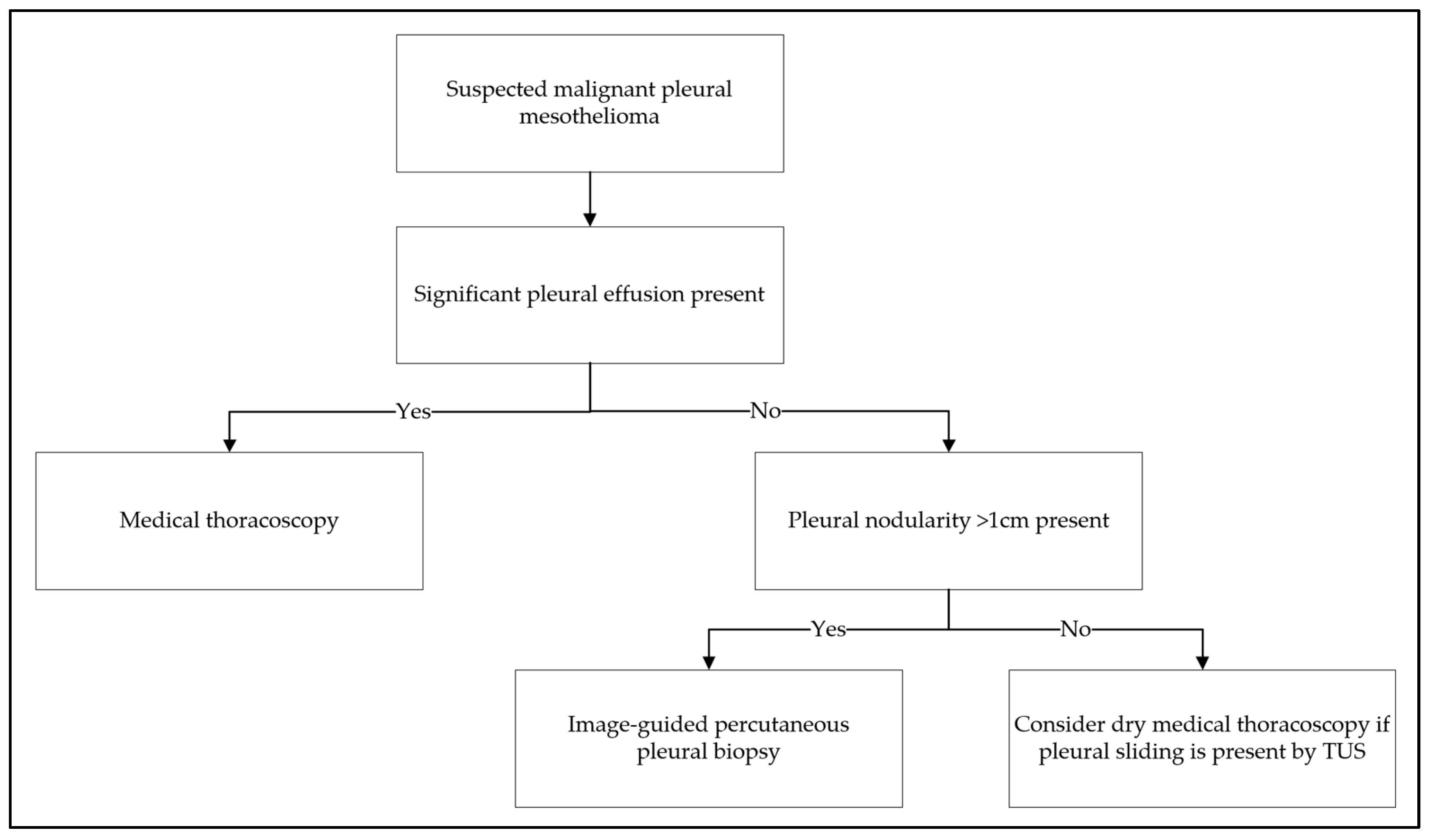

5.2. Thoracic Ultrasound

5.3. Computed Tomography

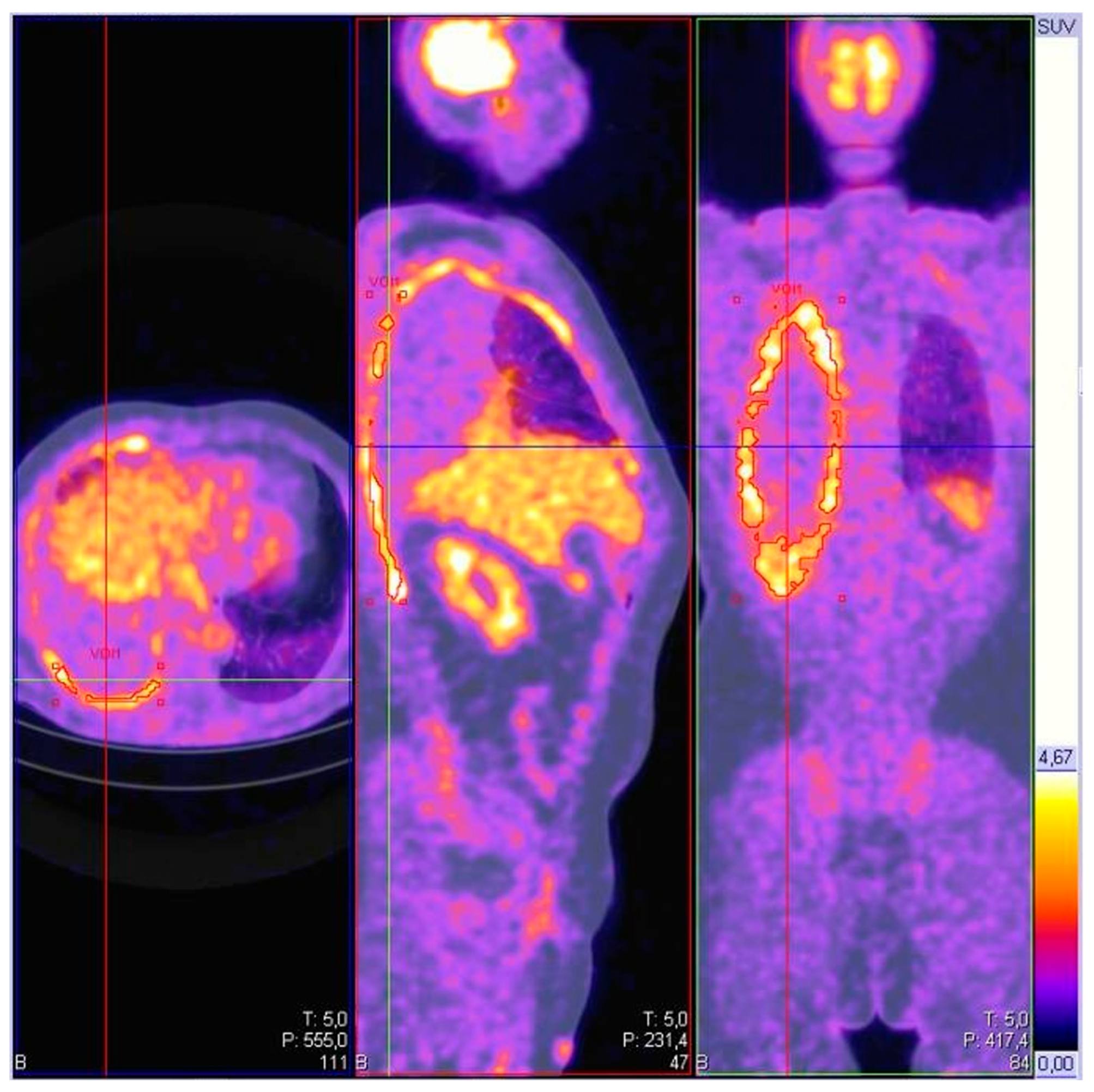

5.4. Positron Emission Tomography

5.5. Magnetic Resonance Imaging

6. Sampling Techniques

6.1. Thoracentesis and Chest Drainage

6.2. Percutaneous Pleural Biopsy

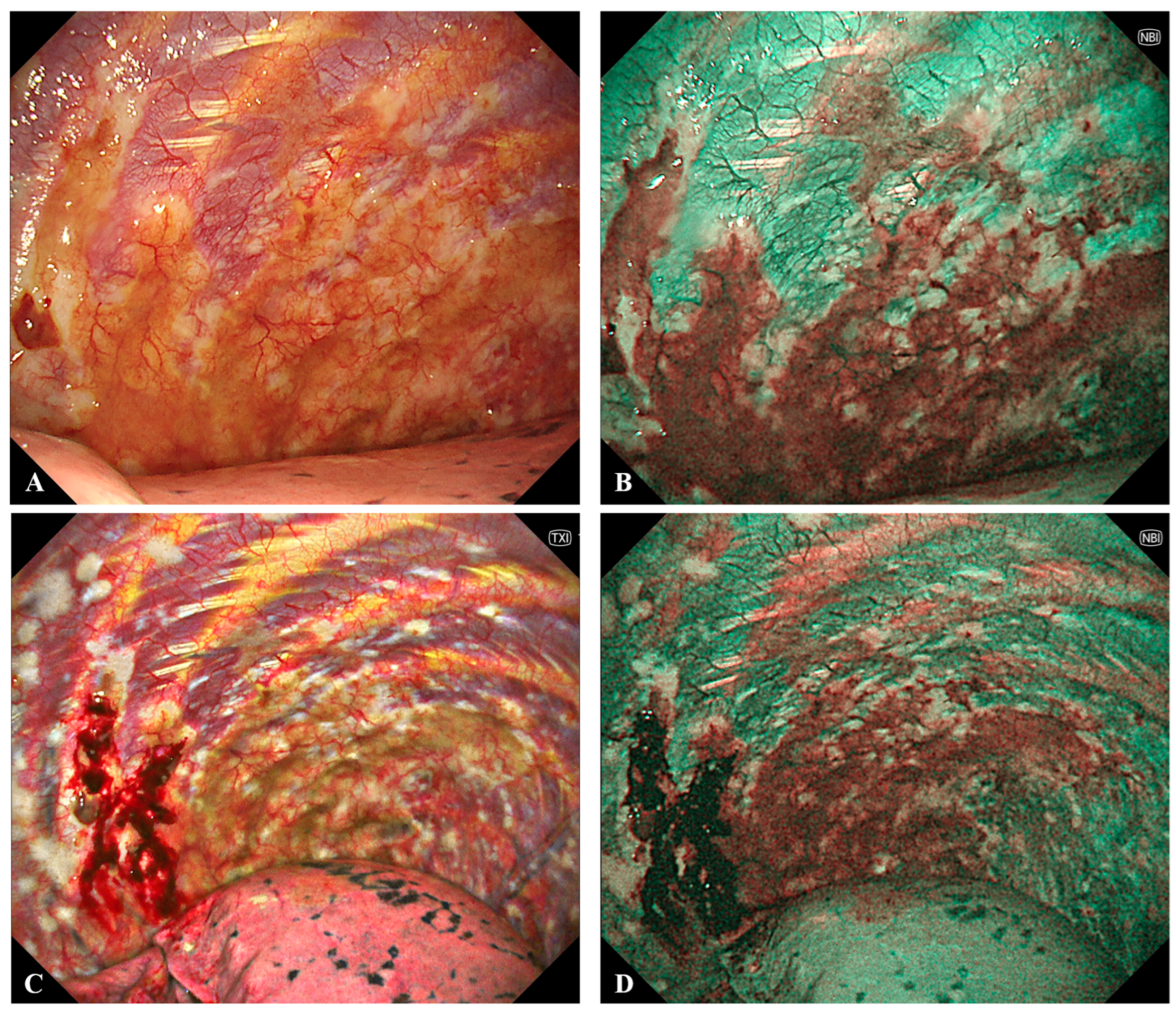

6.3. Medical Thoracoscopy

6.4. EBUS-TBNA and EUS-B

7. Histological Classification

7.1. Different Histotypes and Their Meaning

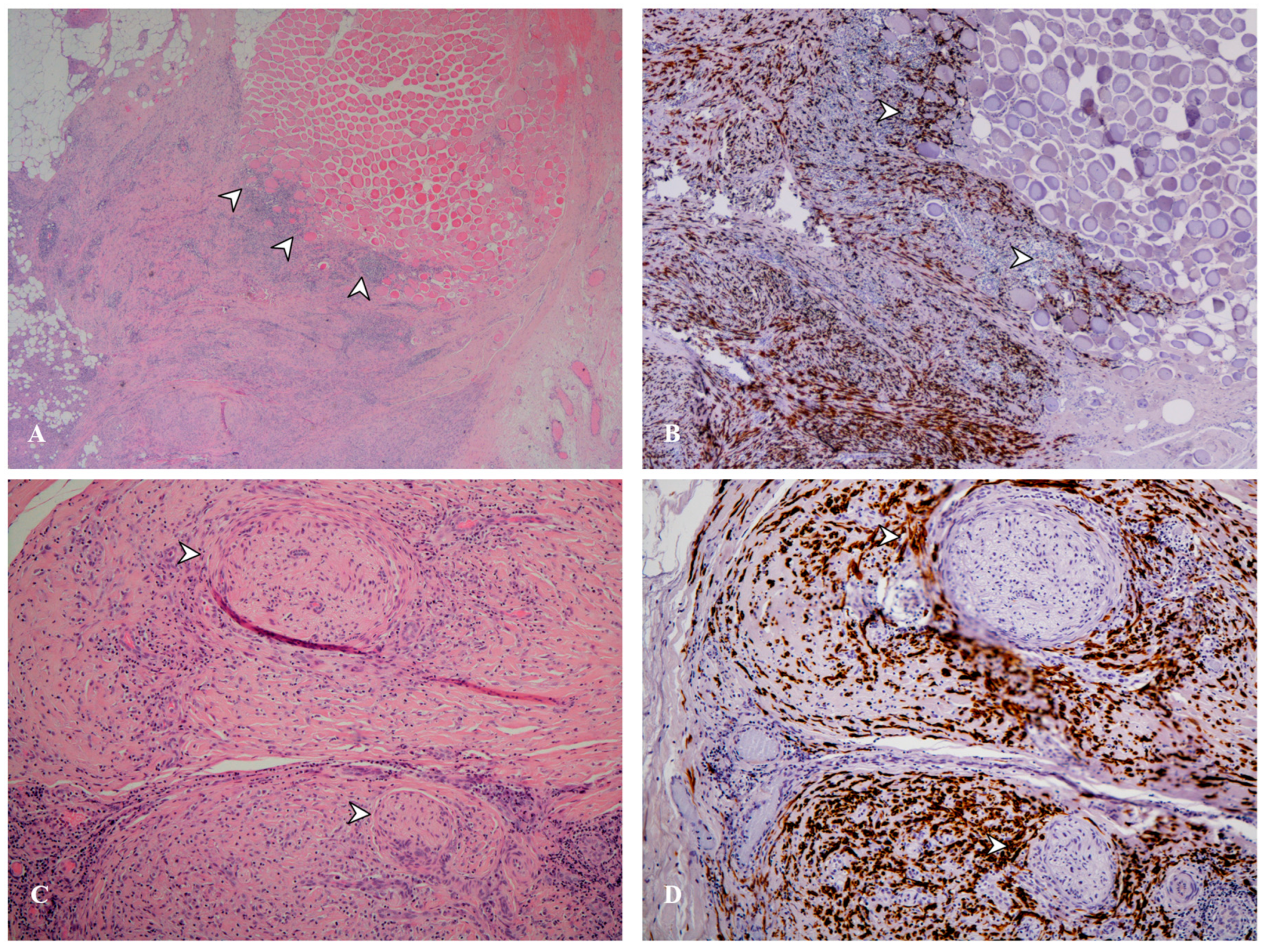

7.2. Immunohistochemistry and Molecular Testing

8. Staging and Multidisciplinary Evaluation

8.1. Current Staging System and Its Clinical Implications

8.2. The Role of the Multidisciplinary Team

9. Emerging Diagnostic Approaches and Biomarkers

9.1. Liquid Biopsies

9.2. Novel Biomarkers

9.3. Advances in Artificial Intelligence and Radiomics

9.4. Other Technologies

10. Communicating the Diagnosis

11. Conclusions and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| ADC | Apparent Diffusion Coefficient |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| BAP1 | BRCA1-Associated Protein 1 |

| BTS | British Thoracic Society |

| CDKN2A | Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Inhibitor 2A |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| CXR | Chest X-ray |

| ctDNA | Circulating Tumor DNA |

| DAMP | Damage-Associated Molecular Pattern |

| DWI | Diffusion-Weighted Imaging |

| eNose | Electronic Nose |

| EBUS-TBNA | Endobronchial Ultrasound-Guided Transbronchial Needle Aspiration |

| EUS-B-FNA | Endoscopic Ultrasound with Bronchoscope-Guided Fine Needle Aspiration |

| EZH2 | Enhancer of Zeste Homolog 2 |

| FAPI | Fibroblast Activation Protein Inhibitor |

| FDG | Fluorodeoxyglucose |

| FISH | Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization |

| Fmax | Maximal Fissural Thickness |

| GC–MS | Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry |

| HMGB1 | High Mobility Group Box 1 |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| IASLC | International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer |

| MDT | Multidisciplinary Team |

| MIS | Mesothelioma In Situ |

| MPM | Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| MT | Medical Thoracoscopy |

| MTAP | Methylthioadenosine Phosphorylase |

| NBI | Narrow Band Imaging |

| NF2 | Neurofibromatosis type 2 |

| PET | Positron Emission Tomography |

| POCUS | Point-of-Care Ultrasound |

| Psum | Sum of Maximum Pleural Thickness |

| RCTs | Randomized Controlled Trials |

| ROSE | Rapid On-Site Evaluation |

| SETD2 | SET Domain containing 2, histone lysine methyltransferase |

| SETDB1 | SET Domain Bifurcated 1 |

| SMRP | Soluble Mesothelin-Related Peptides |

| SUVmax | Maximum Standardized Uptake Value |

| TUS | Thoracic Ultrasound |

| TNM | Tumor, Node, Metastasis Classification |

| TP53 | Tumor Protein p53 |

| VOC | Volatile Organic Compound |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Gunatilake, S.; Lodge, D.; Neville, D.; Jones, T.; Fogg, C.; Bassett, P.; Begum, S.; Kerley, S.; Marshall, L.; Glaysher, S.; et al. Predicting Survival in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma Using Routine Clinical and Laboratory Characteristics. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2021, 8, e000506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviasu, O.; Coleby, D.; Padley, W.; Panchal, R.K.; Hinsliff-Smith, K. Facilitators and Barriers to Early Diagnosis of Pleural Mesothelioma: A Qualitative Study of Patients’ Experiences towards Getting a Diagnosis. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2025, 77, 102927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brims, F. Epidemiology and Clinical Aspects of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Cancers 2021, 13, 4194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madsen, P.H.; Laursen, C.B.; Davidsen, J.R. Diagnostic Delay in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma Due to Physicians Fixation on History with Non-Exposure to Asbestos. BMJ Case Rep. 2013, 2013, bcr2012007491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moro, J.; Sobrero, S.; Cartia, C.F.; Ceraolo, S.; Rapanà, R.; Vaisitti, F.; Ganio, S.; Mellone, F.; Rudella, S.; Scopis, F.; et al. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Challenges of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popat, S.; Baas, P.; Faivre-Finn, C.; Girard, N.; Nicholson, A.G.; Nowak, A.K.; Opitz, I.; Scherpereel, A.; Reck, M. Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Up. Ann. Oncol. 2022, 33, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noonan, C.W. Environmental Asbestos Exposure and Risk of Mesothelioma. Ann. Transl. Med. 2017, 5, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, C.; Bianchi, T. Mesothelioma among Shipyard Workers in Monfalcone, Italy. Indian. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2012, 16, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliore, E.; Consonni, D.; Peters, S.; Vermeulen, R.C.H.; Kromhout, H.; Baldassarre, A.; Cavone, D.; Chellini, E.; Magnani, C.; Mensi, C.; et al. Pleural Mesothelioma Risk by Industry and Occupation: Results from the Multicentre Italian Study on the Etiology of Mesothelioma (MISEM). Environ. Health 2022, 21, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimercati, L.; Cavone, D.; Negrisolo, O.; Pentimone, F.; De Maria, L.; Caputi, A.; Sponselli, S.; Delvecchio, G.; Cafaro, F.; Chellini, E.; et al. Mesothelioma Risk Among Maritime Workers According to Job Title: Data From the Italian Mesothelioma Register (ReNaM). Med. Lav. 2023, 114, e2023038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Mazurek, J.M.; Li, Y.; Blackley, D.; Weissman, D.N.; Burton, S.V.; Amin, W.; Landsittel, D.; Becich, M.J.; Ye, Y. Industry, Occupation, and Exposure History of Mesothelioma Patients in the U.S. National Mesothelioma Virtual Bank, 2006–2022. Environ. Res. 2023, 230, 115085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vimercati, L.; Cavone, D.; De Maria, L.; Caputi, A.; Pentimone, F.; Sponselli, S.; Delvecchio, G.; Chellini, E.; Binazzi, A.; Di Marzio, D.; et al. Mesothelioma Risk among Construction Workers According to Job Title: Data from the Italian Mesothelioma Register. Med. Lav. 2023, 114, e2023025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willis, V.J.; Levin, J.L.; Nessim, D.E. A Review of Job Assignments and Asbestos Workplace Exposure Measurements for TAWP Mesothelioma Deaths Through 2011. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2025, 68, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tlotleng, N.; Sidwell Wilson, K.; Naicker, N.; Koegelenberg, C.F.; Rees, D.; Phillips, J.I. The Significance of Non-occupational Asbestos Exposure in Women with Mesothelioma. Respirol. Case Rep. 2018, 7, e00386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpert, N.; van Gerwen, M.; Flores, R.; Taioli, E. Gender Differences in Outcomes of Patients with Mesothelioma. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 43, 792–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demirer, E.; Ghattas, C.F.; Radwan, M.O.; Elamin, E.M. Clinical and Prognostic Features of Erionite-Induced Malignant Mesothelioma. Yonsei Med. J. 2015, 56, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, J.E.; Nascarella, M.A.; Valberg, P.A. Ionizing Radiation: A Risk Factor for Mesothelioma. Cancer Causes Control 2009, 20, 1237–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visci, G.; Rizzello, E.; Zunarelli, C.; Violante, F.S.; Boffetta, P. Relationship between Exposure to Ionizing Radiation and Mesothelioma Risk: A Systematic Review of the Scientific Literature and Meta-analysis. Cancer Med. 2022, 11, 778–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascoli, V.; Romeo, E.; Carnovale Scalzo, C.; Cozzi, I.; Ancona, L.; Cavariani, F.; Balestri, A.; Gasperini, L.; Forastiere, F. Familial Malignant Mesothelioma: A Population-Based Study in Central Italy (1980–2012). Cancer Epidemiol. 2014, 38, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharazmi, E.; Chen, T.; Fallah, M.; Sundquist, K.; Sundquist, J.; Albin, M.; Weiderpass, E.; Hemminki, K. Familial Risk of Pleural Mesothelioma Increased Drastically in Certain Occupations: A Nationwide Prospective Cohort Study. Eur. J. Cancer 2018, 103, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akarsu, M.; Ak, G.; Dündar, E.; Metintaş, M. Genetic Analysis of Familial Predisposition in the Pathogenesis of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 149, 7767–7778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attanoos, R.L.; Churg, A.; Galateau-Salle, F.; Gibbs, A.R.; Roggli, V.L. Malignant Mesothelioma and Its Non-Asbestos Causes. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2018, 142, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klebe, S.; Hocking, A.J.; Soeberg, M.; Leigh, J. The Significance of Short Latency in Mesothelioma for Attribution of Causation: Report of a Case with Predisposing Germline Mutations and Review of the Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, A.U.; Baris, Y.I.; Dogan, M.; Emri, S.; Steele, I.; Elmishad, A.G.; Carbone, M. Genetic Predisposition to Fiber Carcinogenesis Causes a Mesothelioma Epidemic in Turkey. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 5063–5068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, M.; Emri, S.; Dogan, A.U.; Steele, I.; Tuncer, M.; Pass, H.I.; Baris, Y.I. A Mesothelioma Epidemic in Cappadocia: Scientific Developments and Unexpected Social Outcomes. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2007, 7, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emri, S.A. The Cappadocia Mesothelioma Epidemic: Its Influence in Turkey and Abroad. Ann. Transl. Med. 2017, 5, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, C.; Giarelli, L.; Grandi, G.; Brollo, A.; Ramani, L.; Zuch, C. Latency Periods in Asbestos-Related Mesothelioma of the Pleura. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 1997, 6, 162–166. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, G. The Latency Period of Mesothelioma among a Cohort of British Asbestos Workers (1978–2005). Br. J. Cancer 2013, 109, 1965–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolhouse, I.; Bishop, L.; Darlison, L.; De Fonseka, D.; Edey, A.; Edwards, J.; Faivre-Finn, C.; Fennell, D.A.; Holmes, S.; Kerr, K.M.; et al. British Thoracic Society Guideline for the Investigation and Management of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Thorax 2018, 73, i1–i30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fondo Vittime Amianto|Ministero Del Lavoro e Delle Politiche Sociali. Available online: https://www.lavoro.gov.it/temi-e-priorita/previdenza/focus-on/assicurazione-contro-infortuni-sul-lavoro-e-malattie-professionali/pagine/fondo-vittime-amianto (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Yang, H.; Rivera, Z.; Jube, S.; Nasu, M.; Bertino, P.; Goparaju, C.; Franzoso, G.; Lotze, M.T.; Krausz, T.; Pass, H.I.; et al. Programmed Necrosis Induced by Asbestos in Human Mesothelial Cells Causes High-Mobility Group Box 1 Protein Release and Resultant Inflammation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 12611–12616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jube, S.; Rivera, Z.S.; Bianchi, M.E.; Powers, A.; Wang, E.; Pagano, I.; Pass, H.I.; Gaudino, G.; Carbone, M.; Yang, H. Cancer Cell Secretion of the DAMP Protein HMGB1 Supports Progression in Malignant Mesothelioma. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 3290–3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudino, G.; Xue, J.; Yang, H. How Asbestos and Other Fibers Cause Mesothelioma. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2020, 9, S39–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cigognetti, M.; Lonardi, S.; Fisogni, S.; Balzarini, P.; Pellegrini, V.; Tironi, A.; Bercich, L.; Bugatti, M.; Rossi, G.; Murer, B.; et al. BAP1 (BRCA1-Associated Protein 1) Is a Highly Specific Marker for Differentiating Mesothelioma from Reactive Mesothelial Proliferations. Mod. Pathol. 2015, 28, 1043–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Hall, S.R.R.; Sun, B.; Zhao, L.; Gao, Y.; Schmid, R.A.; Tan, S.T.; Peng, R.-W.; Yao, F. NF2 and Canonical Hippo-YAP Pathway Define Distinct Tumor Subsets Characterized by Different Immune Deficiency and Treatment Implications in Human Pleural Mesothelioma. Cancers 2021, 13, 1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbone, M.; Ferris, L.K.; Baumann, F.; Napolitano, A.; Lum, C.A.; Flores, E.G.; Gaudino, G.; Powers, A.; Bryant-Greenwood, P.; Krausz, T.; et al. BAP1 Cancer Syndrome: Malignant Mesothelioma, Uveal and Cutaneous Melanoma, and MBAITs. J. Transl. Med. 2012, 10, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbone, M.; Pass, H.I.; Ak, G.; Alexander, H.R.; Baas, P.; Baumann, F.; Blakely, A.M.; Bueno, R.; Bzura, A.; Cardillo, G.; et al. Medical and Surgical Care of Mesothelioma Patients and Their Relatives Carrying Germline BAP1 Mutations. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2022, 17, 873–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagogo-Jack, I.; Yeap, B.Y.; Mino-Kenudson, M.; Digumarthy, S.R. Extrathoracic Metastases in Pleural Mesothelioma. JTO Clin. Res. Rep. 2023, 4, 100557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehl, K.; Vrugt, B.; Opitz, I.; Meerang, M. Heterogeneity in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, Y.; Meiller, C.; Quetel, L.; Elarouci, N.; Ayadi, M.; Tashtanbaeva, D.; Armenoult, L.; Montagne, F.; Tranchant, R.; Renier, A.; et al. Dissecting Heterogeneity in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma through Histo-Molecular Gradients for Clinical Applications. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quetel, L.; Meiller, C.; Assié, J.-B.; Blum, Y.; Imbeaud, S.; Montagne, F.; Tranchant, R.; de Wolf, J.; Caruso, S.; Copin, M.-C.; et al. Genetic Alterations of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: Association with Tumor Heterogeneity and Overall Survival. Mol. Oncol. 2020, 14, 1207–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Yang, T.; Yang, T.; Yuan, Y.; Li, F. Unraveling Tumor Microenvironment Heterogeneity in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma Identifies Biologically Distinct Immune Subtypes Enabling Prognosis Determination. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 995651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, V.; Löseke, S.; Nowak, D.; Herth, F.J.F.; Tannapfel, A. Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2013, 110, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, V.; Günthe, S.; Mülle, K.M.; Fischer, M. Malignant Mesothelioma--German Mesothelioma Register 1987–1999. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2001, 74, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordes, M.E.; Brueggen, C. Diffuse Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: Part II. Symptom Management. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2003, 7, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianco, A.; Valente, T.; De Rimini, M.L.; Sica, G.; Fiorelli, A. Clinical Diagnosis of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10, S253–S261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Taheri, Z.M.; Jorda, M. Systemic Lymphadenopathy as the Initial Presentation of Malignant Mesothelioma: A Report of Three Cases. Patholog. Res. Int. 2010, 2010, 846571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, A.; Kundu, S.; Pal, A.; Saha, S. Mesothelioma with Superior Vena Cava Obstruction in Young Female Following Short Latency of Asbestos Exposure. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2015, 11, 940–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozer, N.; Shehu, V.; Aytemir, K.; Ovünç, K.; Emre, S.; Kes, S. Echocardiographic Findings of Pericardial Involvement in Patients with Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma with a History of Environmental Exposure to Asbestos and Erionite. Respirology 2000, 5, 333–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.-P.; Tu, D.-W.; Zhang, T.-W.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Kang, D.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Li, Y.-Y.; Zhang, B.; Han, S.-S.; et al. Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma with Constrictive Pericarditis as the First Manifestation: A Case Report. Clin. Case Rep. 2023, 11, e7555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, E.; Aujayeb, A.; Astoul, P. Diagnosis of Pleural Mesothelioma: Is Everything Solved at the Present Time? Curr. Oncol. 2024, 31, 4968–4983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Stang, N.; Burke, L.; Blaizot, G.; Gibbs, A.R.; Lebailly, P.; Clin, B.; Girard, N.; Galateau-Sallé, F.; MESOPATH and EURACAN networks. Differential Diagnosis of Epithelioid Malignant Mesothelioma With Lung and Breast Pleural Metastasis: A Systematic Review Compared With a Standardized Panel of Antibodies-A New Proposal That May Influence Pathologic Practice. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2020, 144, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauter, J.L.; Dacic, S.; Galateau-Salle, F.; Attanoos, R.L.; Butnor, K.J.; Churg, A.; Husain, A.N.; Kadota, K.; Khoor, A.; Nicholson, A.G.; et al. The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Pleura: Advances Since the 2015 Classification. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2022, 17, 608–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucà, S.; Pignata, G.; Cioce, A.; Salzillo, C.; De Cecio, R.; Ferrara, G.; Della Corte, C.M.; Morgillo, F.; Fiorelli, A.; Montella, M.; et al. Diagnostic Challenges in the Pathological Approach to Pleural Mesothelioma. Cancers 2025, 17, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, M.; Adusumilli, P.S.; Alexander, H.R., Jr.; Baas, P.; Bardelli, F.; Bononi, A.; Bueno, R.; Felley-Bosco, E.; Galateau-Salle, F.; Jablonski, D.; et al. Mesothelioma: Scientific Clues for Prevention, Diagnosis, and Therapy. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 402–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, T.; Fujita, K.; Okamura, M.; Okuno, Y.; Saito, Z.; Kanai, O.; Nakatani, K.; Moriyoshi, K.; Mio, T. Pleural Involvement of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma Mimicking Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Respir. Med. Case Rep. 2020, 31, 101206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchevsky, A.M.; LeStang, N.; Hiroshima, K.; Pelosi, G.; Attanoos, R.; Churg, A.; Chirieac, L.; Dacic, S.; Husain, A.; Khoor, A.; et al. The Differential Diagnosis between Pleural Sarcomatoid Mesothelioma and Spindle Cell/Pleomorphic (Sarcomatoid) Carcinomas of the Lung: Evidence-Based Guidelines from the International Mesothelioma Panel and the MESOPATH National Reference Center. Hum. Pathol. 2017, 67, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J.; Deo, S.V.S.; Kumar, S.; Bhoriwal, S.; Gupta, N.; Saikia, J.; Bhatnagar, S.; Mishra, S.; Bharti, S.; Thulkar, S.; et al. Malignant Chest Wall Tumors: Complex Defects and Their Management-A Review of 181 Cases. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 31, 3675–3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyedi-Sahebari, S.; Amirhoushangi, H.; Rasouli, S.; Hasanzadeh, G.; Imani, A.; Naseri, A.; Nikniaz, L.; Golabi, B.; Frounchi, N.; Montazer, M. Histopathological Features of Chest Wall Masses: A Systematic Review. Ann. Med. Surg. 2025, 87, 2889–2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machida, H.; Naruse, K.; Shinohara, T. Multiple Tumors on the Pleura with Pleural Effusion Mimicking Malignant Mesothelioma. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2022, 95, 95–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreiro, L.; Toubes, M.E.; Rodríguez-Núñez, N.; Valdés, L. Asbestos and Benign Pleural Diseases: A Narrative Review. Breathe 2025, 21, 240236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pairon, J.-C.; Laurent, F.; Rinaldo, M.; Clin, B.; Andujar, P.; Ameille, J.; Brochard, P.; Chammings, S.; Ferretti, G.; Galateau-Sallé, F.; et al. Pleural Plaques and the Risk of Pleural Mesothelioma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2013, 105, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawood, W.; La Garza Henriette, D.; Iliescu, G.; Moran, C.; Grosu, H. Pleural Tuberculosis Mimicking Malignant Mesothelioma. Respir. Med. Case Rep. 2019, 29, 100964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, A.L.; Castro, C.Y.; Singh, S.P.; Moran, C.A. Pleural Amyloidosis Mimicking Mesothelioma: A Clinicopathologic Study of Two Cases. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 2001, 5, 229–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lococo, F.; Di Stefano, T.; Rapicetta, C.; Piro, R.; Gelli, M.C.; Muratore, F.; Ricchetti, T.; Taddei, S.; Zizzo, M.; Cesario, A.; et al. Thoracic Hyper-IgG4-Related Disease Mimicking Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Lung 2019, 197, 387–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, R.; Khan, M.A.; El Khoury, A.; AlMahdy, A.; Hishmeh, M.A. Rheumatoid Arthritis Associated Recurrent Pleural Effusion. Respir. Med. Case Rep. 2024, 52, 102129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaralingam, A.; Aujayeb, A.; Jackson, K.A.; Pellas, E.I.; Khan, I.I.; Chohan, M.T.; Joosten, R.; Boersma, A.; Kerkhoff, J.; Bielsa, S.; et al. Investigation and Outcomes in Patients with Nonspecific Pleuritis: Results from the International Collaborative Effusion Database. ERJ Open Res. 2023, 9, 00599–02022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapel, D.B.; Schulte, J.J.; Husain, A.N.; Krausz, T. Application of Immunohistochemistry in Diagnosis and Management of Malignant Mesothelioma. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2020, 9, S3–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Medina, R.; Castañeda-González, J.P.; Chaves-Cabezas, V.; Alzate, J.P.; Chaves, J.J. Diagnostic Performance of Immunohistochemistry Markers for Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma Diagnosis and Subtypes. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2024, 257, 155276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, A.N.; Colby, T.V.; Ordóñez, N.G.; Krausz, T.; Borczuk, A.; Cagle, P.T.; Chirieac, L.R.; Churg, A.; Galateau-Salle, F.; Gibbs, A.R.; et al. Guidelines for Pathologic Diagnosis of Malignant Mesothelioma: A Consensus Statement from the International Mesothelioma Interest Group. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2009, 133, 1317–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, A.N.; Chapel, D.B.; Attanoos, R.; Beasley, M.B.; Brcic, L.; Butnor, K.; Chirieac, L.R.; Churg, A.; Dacic, S.; Galateau-Salle, F.; et al. Guidelines for Pathologic Diagnosis of Mesothelioma: 2023 Update of the Consensus Statement From the International Mesothelioma Interest Group. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2024, 148, 1251–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aujayeb, A.; Astoul, P. A Diagnostic Approach to Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Pulm. Ther. 2025, 11, 503–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibby, A.C.; Tsim, S.; Kanellakis, N.; Ball, H.; Talbot, D.C.; Blyth, K.G.; Maskell, N.A.; Psallidas, I. Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: An Update on Investigation, Diagnosis and Treatment. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2016, 25, 472–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saracino, L.; Bortolotto, C.; Tomaselli, S.; Fraolini, E.; Bosio, M.; Accordino, G.; Agustoni, F.; Abbott, D.M.; Pozzi, E.; Eleftheriou, D.; et al. Integrating Data from Multidisciplinary Management of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: A Cohort Study. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holzknecht, A.; Illini, O.; Hochmair, M.J.; Krenbek, D.; Setinek, U.; Huemer, F.; Bitterlich, E.; Kaindl, C.; Getman, V.; Akan, A.; et al. Multimodal Treatment of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: Real-World Experience with 112 Patients. Cancers 2022, 14, 2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guadagni, S.; Masedu, F.; Zoras, O.; Zavattieri, G.; Aigner, K.; Guadagni, V.; Fumi, L.; Clementi, M. Multidisciplinary Palliative Treatment Including Isolated Thoracic Perfusion for Progressive Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: A Retrospective Observational Study. J. BUON 2019, 24, 1259–1267. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinale, L.; Ardissone, F.; Gned, D.; Sverzellati, N.; Piacibello, E.; Veltri, A. Diagnostic Imaging and Workup of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Acta Biomed. 2017, 88, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, C.; Lee, Y.C.G.; Maskell, N. BTS Pleural Guideline Group Investigation of a Unilateral Pleural Effusion in Adults: British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Guideline 2010. Thorax 2010, 65 (Suppl. 2), ii4–ii17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherpereel, A.; Opitz, I.; Berghmans, T.; Psallidas, I.; Glatzer, M.; Rigau, D.; Astoul, P.; Bölükbas, S.; Boyd, J.; Coolen, J.; et al. ERS/ESTS/EACTS/ESTRO Guidelines for the Management of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 55, 1900953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibby, A.C.; Halford, P.; De Fonseka, D.; Morley, A.J.; Smith, S.; Maskell, N.A. The Prevalence and Clinical Relevance of Nonexpandable Lung in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. A Prospective, Single-Center Cohort Study of 229 Patients. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2019, 16, 1273–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, N.R.; Gleeson, F.V. Imaging of Pleural Disease. Clin. Chest Med. 2006, 27, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiroshita, A.; Nozaki, S.; Tanaka, Y.; Luo, Y.; Kataoka, Y. Thoracic Ultrasound for Malignant Pleural Effusion: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. ERJ Open Res. 2020, 6, 00464–02020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asciak, R.; Bedawi, E.O.; Bhatnagar, R.; Clive, A.O.; Hassan, M.; Lloyd, H.; Reddy, R.; Roberts, H.; Rahman, N.M. British Thoracic Society Clinical Statement on Pleural Procedures. Thorax 2023, 78, s43–s68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salamonsen, M.; Dobeli, K.; McGrath, D.; Readdy, C.; Ware, R.; Steinke, K.; Fielding, D. Physician-Performed Ultrasound Can Accurately Screen for a Vulnerable Intercostal Artery Prior to Chest Drainage Procedures. Respirology 2013, 18, 942–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stigt, J.A.; Boers, J.E.; Groen, H.J.M. Analysis of “Dry” Mesothelioma with Ultrasound Guided Biopsies. Lung Cancer 2012, 78, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messina, G.; Bove, M.; Natale, G.; Di Filippo, V.; Opromolla, G.; Rainone, A.; Leonardi, B.; Martone, M.; Fiorelli, A.; Vicidomini, G.; et al. Diagnosis of Malignant Pleural Disease: Ultrasound as “a Detective Probe”. Thorac. Cancer 2022, 14, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussuges, A.; Gole, Y.; Blanc, P. Diaphragmatic Motion Studied by M-Mode Ultrasonography: Methods, Reproducibility, and Normal Values. Chest 2009, 135, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.; Jenkins, S.; Eastwood, P.R.; Lee, Y.C.G.; Singh, B. Physiology of Breathlessness Associated with Pleural Effusions. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2015, 21, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjaellegaard, K.; Koefod Petersen, J.; Alstrup, G.; Skaarup, S.; Frost Clementsen, P.; Laursen, C.B.; Bhatnagar, R.; Bodtger, U. Ultrasound in Predicting Improvement in Dyspnoea after Therapeutic Thoracentesis in Patients with Recurrent Unilateral Pleural Effusion. Eur. Clin. Respir. J. 2024, 11, 2337446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalaby, H.M.; Ezzelregal, H.G. Assessment of Diaphragmatic Role in Dyspneic Patients with Pleural Effusion. Egypt. J. Bronchol. 2022, 16, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussuges, A.; Finance, J.; Chaumet, G.; Brégeon, F. Diaphragmatic Motion Recorded by M-Mode Ultrasonography: Limits of Normality. ERJ Open Res. 2021, 7, 00714–02020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safai Zadeh, E.; Görg, C.; Prosch, H.; Horn, R.; Jenssen, C.; Dietrich, C.F. The Role of Thoracic Ultrasound for Diagnosis of Diseases of the Chest Wall, the Mediastinum, and the Diaphragm-Narrative Review and Pictorial Essay. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herth, F. Diagnosis and Staging of Mesothelioma Transthoracic Ultrasound. Lung Cancer 2004, 45 (Suppl. 1), S63–S67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.K.; Kim, J.S.; Lee, K.W.; Yi, C.A.; Goo, J.M.; Jung, S.-H. Multidetector CT Findings and Differential Diagnoses of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma and Metastatic Pleural Diseases in Korea. Korean J. Radiol. 2016, 17, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luerken, L.; Thurn, P.L.; Zeman, F.; Stroszczynski, C.; Hamer, O.W. Conspicuity of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma in Contrast Enhanced MDCT—Arterial Phase or Late Phase? BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.S.; Munden, R.F.; Libshitz, H.I. Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: The Spectrum of Manifestations on CT in 70 Cases. Clin. Radiol. 1999, 54, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bille, A.; Ripley, R.T.; Giroux, D.J.; Gill, R.R.; Kindler, H.L.; Nowak, A.K.; Opitz, I.; Pass, H.I.; Wolf, A.; Rice, D.; et al. The International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Mesothelioma Staging Project: Proposals for the “N” Descriptors in the Forthcoming Ninth Edition of the TNM Classification for Pleural Mesothelioma. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2024, 19, 1326–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, D.J.; Nowak, A.K.; Frauenfelder, T.; Ginsberg, M.S.; Kodama, H.; Lenge de Rosen, V.; Mayoral, M.; Straus, C.; Benedetti, G.; Rusch, V.W.; et al. Radiologist’s Guide to the Ninth Edition TNM Staging System for Quantitative and Qualitative Assessment of Pleural Mesothelioma. Radiology 2025, 316, e250531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Wang, K.; Li, W.; Liu, D. Chest Ultrasound Is Better than CT in Identifying Septated Effusion of Patients with Pleural Disease. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iadevaia, C.; D’Agnano, V.; Pagliaro, R.; Nappi, F.; Lucci, R.; Massa, S.; Bianco, A.; Perrotta, F. Diagnostic Accuracy of Ultrasound Guided Percutaneous Pleural Needle Biopsy for Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, K.; Gemba, K.; Fujimoto, N.; Aoe, K.; Takeshima, Y.; Inai, K.; Kishimoto, T. Computed Tomographic Features of Malignant Peritoneal Mesothelioma. Anticancer Res. 2016, 36, 1067–1072. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tsim, S.; Stobo, D.B.; Alexander, L.; Kelly, C.; Blyth, K.G. The Diagnostic Performance of Routinely Acquired and Reported Computed Tomography Imaging in Patients Presenting with Suspected Pleural Malignancy. Lung Cancer 2017, 103, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falaschi, F.; Romei, C.; Fiorini, S.; Lucchi, M. Imaging of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: It Is Possible a Screening or Early Diagnosis Program?—A Systematic Review about the Use of Screening Programs in a Population of Asbestos Exposed Workers. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, S.I.; Straus, C.M.; Roshkovan, L.; Blyth, K.G.; Frauenfelder, T.; Gill, R.R.; Lalezari, F.; Erasmus, J.; Nowak, A.K.; Gerbaudo, V.H.; et al. Considerations for Imaging of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: A Consensus Statement from the International Mesothelioma Interest Group. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2023, 18, 278–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopci, E.; Castello, A.; Mansi, L. FDG PET/CT for Staging and Restaging Malignant Mesothelioma. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2022, 52, 806–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopci, E.; Kobe, C.; Gnanasegaran, G.; Adam, J.A.; de Geus-Oei, L.-F. PET/CT Variants and Pitfalls in Lung Cancer and Mesothelioma. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2021, 51, 458–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandach, P.; Seifert, R.; Fendler, W.P.; Hautzel, H.; Herrmann, K.; Maier, S.; Plönes, T.; Metzenmacher, M.; Ferdinandus, J. A Role for PET/CT in Response Assessment of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2022, 52, 816–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Kan, Y.; Wang, W.; Yang, J. Prognostic Value of 18F-FDG PET/CT in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: A Meta-Analysis. Acta Radiol. 2023, 64, 552–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Fonseka, D.; Arnold, D.T.; Smartt, H.J.M.; Culliford, L.; Stadon, L.; Tucker, E.; Morley, A.; Zahan-Evans, N.; Bibby, A.C.; Lynch, G.; et al. PET-CT-Guided versus CT-Guided Biopsy in Suspected Malignant Pleural Thickening: A Randomised Trial. Eur. Respir. J. 2024, 63, 2301295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, A.; Zhao, B.; Cheng, C.; Zuo, C. 68 Ga-FAPI-04 Versus 18 F-FDG PET/CT in Detection of Epithelioid Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2022, 47, 980–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güzel, Y.; Kömek, H.; Can, C.; Kaplan, İ.; Kepenek, F.; Ebinç, S.; Büyükdeniz, M.P.; Gündoğan, C.; Oruç, Z. Comparison of the Role of 18 F-Fluorodeoxyglucose PET/Computed Tomography and 68 Ga-Labeled FAP Inhibitor-04 PET/CT in Patients with Malignant Mesothelioma. Nucl. Med. Commun. 2023, 44, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, L.; Schwaning, F.; Metzenmacher, M.; Pabst, K.; Siveke, J.; Trajkovic-Arsic, M.; Schaarschmidt, B.; Wiesweg, M.; Aigner, C.; Plönes, T.; et al. Fibroblast Activation Protein-Directed Imaging Outperforms 18F-FDG PET/CT in Malignant Mesothelioma: A Prospective, Single-Center, Observational Trial. J. Nucl. Med. 2024, 65, 1188–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirienko, M.; Gelardi, F.; Fiz, F.; Bauckneht, M.; Ninatti, G.; Pini, C.; Briganti, A.; Falconi, M.; Oyen, W.J.G.; van der Graaf, W.T.A.; et al. Personalised PET Imaging in Oncology: An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses to Guide the Appropriate Radiopharmaceutical Choice and Indication. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2024, 52, 208–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsim, S.; Cowell, G.W.; Kidd, A.; Woodward, R.; Alexander, L.; Kelly, C.; Foster, J.E.; Blyth, K.G. A Comparison between MRI and CT in the Assessment of Primary Tumour Volume in Mesothelioma. Lung Cancer 2020, 150, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, R.R.; Umeoka, S.; Mamata, H.; Tilleman, T.R.; Stanwell, P.; Woodhams, R.; Padera, R.F.; Sugarbaker, D.J.; Hatabu, H. Diffusion-Weighted MRI of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: Preliminary Assessment of Apparent Diffusion Coefficient in Histologic Subtypes. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2010, 195, W125–W130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usuda, K.; Iwai, S.; Funasaki, A.; Sekimura, A.; Motono, N.; Matoba, M.; Doai, M.; Yamada, S.; Ueda, Y.; Uramoto, H. Diffusion-Weighted Imaging Can Differentiate between Malignant and Benign Pleural Diseases. Cancers 2019, 11, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loveland, P.; Christie, M.; Hammerschlag, G.; Irving, L.; Steinfort, D. Diagnostic Yield of Pleural Fluid Cytology in Malignant Effusions: An Australian Tertiary Centre Experience. Intern. Med. J. 2018, 48, 1318–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, D.T.; Fonseka, D.D.; Perry, S.; Morley, A.; Harvey, J.E.; Medford, A.; Brett, M.; Maskell, N.A. Investigating Unilateral Pleural Effusions: The Role of Cytology. Eur. Respir. J. 2018, 52, 1801254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruno, R.; Alì, G.; Poma, A.M.; Proietti, A.; Libener, R.; Mariani, N.; Niccoli, C.; Chella, A.; Ribechini, A.; Grosso, F.; et al. Differential Diagnosis of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma on Cytology: A Gene Expression Panel versus BRCA1-Associated Protein 1 and P16 Tests. J. Mol. Diagn. 2020, 22, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassirian, S.; Hinton, S.N.; Cuninghame, S.; Chaudhary, R.; Iansavitchene, A.; Amjadi, K.; Dhaliwal, I.; Zeman-Pocrnich, C.; Mitchell, M.A. Diagnostic Sensitivity of Pleural Fluid Cytology in Malignant Pleural Effusions: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Thorax 2023, 78, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klempman, S. The Exfoliative Cytology of Diffuse Pleural Mesothelioma. Cancer 1962, 15, 691–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, C.W. The Cytologic Diagnosis of Mesothelioma: Are We There Yet? J. Am. Soc. Cytopathol. 2023, 12, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheaff, M. Guidelines for the Cytopathologic Diagnosis of Epithelioid and Mixed-Type Malignant Mesothelioma: Complementary Statement from the International Mesothelioma Interest Group, Also Endorsed by the International Academy of Cytology and the Papanicolaou Society of Cytopathology. A Proposal to Be Applauded and Promoted but Which Requires Updating. Diagn. Cytopathol. 2020, 48, 877–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M.E.; Rahman, N.M.; Maskell, N.A.; Bibby, A.C.; Blyth, K.G.; Corcoran, J.P.; Edey, A.; Evison, M.; de Fonseka, D.; Hallifax, R.; et al. British Thoracic Society Guideline for Pleural Disease. Thorax 2023, 78, s1–s42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Own, S.A.; Höijer, J.; Hillerdahl, G.; Dobra, K.; Hjerpe, A. Effusion Cytology of Malignant Mesothelioma Enables Earlier Diagnosis and Recognizes Patients with Better Prognosis. Diagn. Cytopathol. 2021, 49, 606–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortin, M.; Tremblay, A. Pleural Controversies: Indwelling Pleural Catheter vs. Pleurodesis for Malignant Pleural Effusions. J. Thorac. Dis. 2015, 7, 1052–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mierzejewski, M.; Korczynski, P.; Krenke, R.; Janssen, J.P. Chemical Pleurodesis—A Review of Mechanisms Involved in Pleural Space Obliteration. Respir. Res. 2019, 20, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiroshita, A.; Kurosaki, M.; Takeshita, M.; Kataoka, Y. Medical Thoracoscopy, Computed Tomography-Guided Biopsy, and Ultrasound-Guided Biopsy for Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: A Systematic Review. Anticancer Res. 2021, 41, 2217–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Tang, J.; Zhou, X.; Chen, W.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Zhou, D.; He, L.; Tang, Q. Diagnostic Ability and Its Influenced Factors of Ultrasound-Guided Percutaneous Pleural Needle Biopsy Diagnosis for Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Front. Surg. 2022, 9, 1022505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.F.; Gray, W.; Davies, R.J.; Gleeson, F.V. Percutaneous Image-Guided Cutting Needle Biopsy of the Pleura in the Diagnosis of Malignant Mesothelioma. Chest 2001, 120, 1798–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzinski, M.; Puła, M.; Zdanowicz, A.; Kacała, A.; Dudek, K.; Lipiński, A.; Sąsiadek, M. Safety, Feasibility, and Effectiveness of a CT-Guided Transthoracic Lung and Pleural Biopsy—A Single-Centre Experience with Own Low-Dose Protocol. Pol. J. Radiol. 2023, 88, e546–e551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Shen, K.; Lv, T.; Liu, H.; Wang, Z.; Wu, J.; Zhang, H.; Colella, S.; Wu, F.-Z.; Milano, M.T.; et al. Comparison between Closed Pleural Biopsy and Medical Thoracoscopy for the Diagnosis of Undiagnosed Exudative Pleural Effusions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2020, 9, 446–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metintas, M.; Ak, G.; Dundar, E.; Yildirim, H.; Ozkan, R.; Kurt, E.; Erginel, S.; Alatas, F.; Metintas, S. Medical Thoracoscopy vs CT Scan-Guided Abrams Pleural Needle Biopsy for Diagnosis of Patients with Pleural Effusions: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Chest 2010, 137, 1362–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Zayas, G.; Molina, S.; Ost, D.E. Sensitivity and Complications of Thoracentesis and Thoracoscopy: A Meta-Analysis. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2022, 31, 220053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, K.J.; Leong, C.K.-L.; Young, S.L.; Chua, B.L.W.; Wong, J.J.Y.; Phua, I.G.C.S.; Lim, W.T.; Anantham, D.; Tan, Q.L. Diagnostic Value and Safety of Medical Thoracoscopy in Undiagnosed Pleural Effusions—A Prospective Observational Cohort Study. J. Thorac. Dis. 2024, 16, 3142–3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.A.I.; Ambalavanan, S.; Thomson, D.; Miles, J.; Munavvar, M. A Comparison of the Diagnostic Yield of Rigid and Semirigid Thoracoscopes. J. Bronchol. Interv. Pulmonol. 2012, 19, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Aggarwal, A.N.; Gupta, D. Diagnostic Accuracy and Safety of Semirigid Thoracoscopy in Exudative Pleural Effusions: A Meta-Analysis. Chest 2013, 144, 1857–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhooria, S.; Singh, N.; Aggarwal, A.N.; Gupta, D.; Agarwal, R. A Randomized Trial Comparing the Diagnostic Yield of Rigid and Semirigid Thoracoscopy in Undiagnosed Pleural Effusions. Respir. Care 2014, 59, 756–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiq, M.; Sethi, J.; Ali, M.S.; Ghori, U.K.; Saghaie, T.; Folch, E. Pleural Cryobiopsy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Chest 2020, 157, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loddenkemper, R.; Lee, P.; Noppen, M.; Mathur, P.N. Medical Thoracoscopy/Pleuroscopy: Step by Step. Breathe 2011, 8, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönfeld, N.; Schwarz, C.; Kollmeier, J.; Blum, T.; Bauer, T.T.; Ott, S. Narrow Band Imaging (NBI) during Medical Thoracoscopy: First Impressions. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2009, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, F.; Tong, Z. Application of Narrow-Band Imaging Thoracoscopy in Diagnosis of Pleural Diseases. Postgrad. Med. 2020, 132, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imabayashi, T.; Matsumoto, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Nakai, T.; Tsuchida, T. Pleural Staging Using Local Anesthetic Thoracoscopy in Dry Pleural Dissemination and Minimal Pleural Effusion. Thorac. Cancer 2021, 12, 1195–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nour Moursi Ahmed, S.; Saka, H.; Mohammadien, H.A.; Alkady, O.; Oki, M.; Tanikawa, Y.; Tsuboi, R.; Aoyama, M.; Sugiyama, K. Safety and Complications of Medical Thoracoscopy. Adv. Med. 2016, 2016, 3794791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.-Y.; Zhai, C.-C.; Lin, X.-S.; Yao, Z.-H.; Liu, Q.-H.; Zhu, L.; Li, D.-Z.; Li, X.-L.; Wang, N.; Lin, D.-J. Safety and Complications of Medical Thoracoscopy in the Management of Pleural Diseases. BMC Pulm. Med. 2019, 19, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.A.; Li, P.; Pease, C.; Hosseini, S.; Souza, C.; Zhang, T.; Amjadi, K. Catheter Tract Metastasis in Mesothelioma Patients with Indwelling Pleural Catheters: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Respiration 2019, 97, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapidot, M.; Mazzola, E.; Bueno, R. Malignant Local Seeding in Procedure Tracts of Pleural Mesothelioma: Incidence and Novel Risk Factors in 308 Patients. Cancers 2025, 17, 2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosu, H.B.; Vial-Rodriguez, M.; Vakil, E.; Casal, R.F.; Eapen, G.A.; Morice, R.; Stewart, J.; Sarkiss, M.G.; Ost, D.E. Pleural Touch Preparations and Direct Visualization of the Pleura during Medical Thoracoscopy for the Diagnosis of Malignancy. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2017, 14, 1326–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosu, H.B.; Kern, R.; Maldonado, F.; Casal, R.; Andersen, C.R.; Li, L.; Eapen, G.; Ost, D.; Jimenez, C.; Frangopoulos, F.; et al. Predicting Malignant Pleural Effusion during Diagnostic Pleuroscopy with Biopsy: A Prospective Multicentre Study. Respirology 2022, 27, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Ren, T.; Luo, G.; You, H.; Wang, X.; Li, D.; Wang, L.; Wang, M. Rapid On-Site Evaluation of Touch Imprints of Medical Thoracoscopy Biopsy Tissue for the Management of Pleural Disease. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1196000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Li, Z.; Xu, N.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Lin, D. Efficacy of Medical Thoracoscopic Talc Pleurodesis in Malignant Pleural Effusion Caused by Different Types of Tumors and Different Pathological Classifications of Lung Cancer. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 8, 18945–18953. [Google Scholar]

- Fantin, A.; Castaldo, N.; Palou, M.S.; Viterale, G.; Crisafulli, E.; Sartori, G.; Patrucco, F.; Vailati, P.; Morana, G.; Mei, F.; et al. Beyond Diagnosis: A Narrative Review of the Evolving Therapeutic Role of Medical Thoracoscopy in the Management of Pleural Diseases. J. Thorac. Dis. 2024, 16, 2177–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, G.; de Fonseka, D.; Maskell, N. Pleural Controversies: Image Guided Biopsy vs. Thoracoscopy for Undiagnosed Pleural Effusions? J. Thorac. Dis. 2015, 7, 1041–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassanein, E.G.; El Ganady, A.A.; El Hoshy, M.S.; Ashry, M.S. Comparative Study between the Use of Image Guided Pleural Biopsy Using Abram’s Needle and Medical Thoracoscope in Diagnosis of Exudative Pleural Effusion. Egypt. J. Chest Dis. Tuberc. 2017, 66, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Gupta, N.; Ish, P.; Kaushik, R.; Gupta, N.K.; Talukdar, T.; Kumar, R. Comparative Study between Ultrasound-Guided Closed Pleural Biopsy and Thoracoscopic Pleural Biopsy in Undiagnosed Exudative Pleural Effusions. Monaldi Arch. Chest Dis. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghigna, M.R.; Crutu, A.; Florea, V.; Soummer-Feulliet, S.; Baldeyrou, P. The Role of Endobronchial Ultrasound-Guided Fine Needle Aspiration in the Diagnosis of Pleural Mesothelioma. Cytopathology 2016, 27, 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, D.C.; Steliga, M.A.; Stewart, J.; Eapen, G.; Jimenez, C.A.; Lee, J.H.; Hofstetter, W.L.; Marom, E.M.; Mehran, R.J.; Vaporciyan, A.A.; et al. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Fine Needle Aspiration for Staging of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2009, 88, 862–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnecka-Kujawa, K.; de Perrot, M.; Keshavjee, S.; Yasufuku, K. Endobronchial Ultrasound-Guided Transbronchial Needle Aspiration Mediastinal Lymph Node Staging in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. J. Thorac. Dis. 2019, 11, 602–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piro, R.; Fontana, M.; Livrieri, F.; Menzella, F.; Casalini, E.; Taddei, S.; De Giorgi, F.; Facciolongo, N. Pleural Mesothelioma: When Echo-endoscopy (EUS-B-FNA) Leads to Diagnosis in a Minimally Invasive Way. Thorac. Cancer 2021, 12, 981–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alchami, F.S.; Attanoos, R.L.; Bamber, A.R. Myxoid Variant Epithelioid Pleural Mesothelioma Defines a Favourable Prognosis Group: An Analysis of 191 Patients with Pleural Malignant Mesothelioma. J. Clin. Pathol. 2017, 70, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shia, J.; Qin, J.; Erlandson, R.A.; King, R.; Illei, P.; Nobrega, J.; Yao, D.; Klimstra, D.S. Malignant Mesothelioma with a Pronounced Myxoid Stroma: A Clinical and Pathological Evaluation of 19 Cases. Virchows Arch. 2005, 447, 828–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez, N.G. Mesothelioma with Rhabdoid Features: An Ultrastructural and Immunohistochemical Study of 10 Cases. Mod. Pathol. 2006, 19, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez, N.G. Pleomorphic Mesothelioma: Report of 10 Cases. Mod. Pathol. 2012, 25, 1011–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, L.E.; Karrison, T.; Ananthanarayanan, V.; Gallan, A.J.; Adusumilli, P.S.; Alchami, F.S.; Attanoos, R.; Brcic, L.; Butnor, K.J.; Galateau-Sallé, F.; et al. Nuclear Grade and Necrosis Predict Prognosis in Malignant Epithelioid Pleural Mesothelioma: A Multi-Institutional Study. Mod. Pathol. 2018, 31, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadota, K.; Suzuki, K.; Colovos, C.; Sima, C.S.; Rusch, V.W.; Travis, W.D.; Adusumilli, P.S. A Nuclear Grading System Is a Strong Predictor of Survival in Epitheloid Diffuse Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Mod. Pathol. 2012, 25, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churg, A.; Nabeshima, K.; Ali, G.; Bruno, R.; Fernandez-Cuesta, L.; Galateau-Salle, F. Highlights of the 14th International Mesothelioma Interest Group Meeting: Pathologic Separation of Benign from Malignant Mesothelial Proliferations and Histologic/Molecular Analysis of Malignant Mesothelioma Subtypes. Lung Cancer 2018, 124, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtiol, P.; Maussion, C.; Moarii, M.; Pronier, E.; Pilcer, S.; Sefta, M.; Manceron, P.; Toldo, S.; Zaslavskiy, M.; Le Stang, N.; et al. Deep Learning-Based Classification of Mesothelioma Improves Prediction of Patient Outcome. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1519–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacic, S.; Le Stang, N.; Husain, A.; Weynand, B.; Beasley, M.B.; Butnor, K.; Chapel, D.; Gibbs, A.; Klebe, S.; Lantuejoul, S.; et al. Interobserver Variation in the Assessment of the Sarcomatoid and Transitional Components in Biphasic Mesotheliomas. Mod. Pathol. 2020, 33, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galateau Salle, F.; Le Stang, N.; Tirode, F.; Courtiol, P.; Nicholson, A.G.; Tsao, M.-S.; Tazelaar, H.D.; Churg, A.; Dacic, S.; Roggli, V.; et al. Comprehensive Molecular and Pathologic Evaluation of Transitional Mesothelioma Assisted by Deep Learning Approach: A Multi-Institutional Study of the International Mesothelioma Panel from the MESOPATH Reference Center. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2020, 15, 1037–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, D.W.; Attwood, H.D.; Constance, T.J.; Shilkin, K.B.; Steele, R.H. Lymphohistiocytoid Mesothelioma: A Rare Lymphomatoid Variant of Predominantly Sarcomatoid Mesothelioma. Ultrastruct. Pathol. 1988, 12, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galateau-Sallé, F.; Attanoos, R.; Gibbs, A.R.; Burke, L.; Astoul, P.; Rolland, P.; Ilg, A.G.s.; Pairon, J.C.; Brochard, P.; Begueret, H.; et al. Lymphohistiocytoid Variant of Malignant Mesothelioma of the Pleura: A Series of 22 Cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2007, 31, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, T.; Hiroi, S.; Nakanishi, K.; Takagawa, K.; Haba, R.; Hayashi, K.; Kawachi, K.; Nozawa, A.; Hebisawa, A.; Nakatani, Y. Lymphohistiocytoid Mesothelioma of the Pleura. Pathol. Int. 2010, 60, 566–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churg, A.; Hwang, H.; Tan, L.; Qing, G.; Taher, A.; Tong, A.; Bilawich, A.M.; Dacic, S. Malignant Mesothelioma in Situ. Histopathology 2018, 72, 1033–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Churg, A.; Galateau-Salle, F.; Roden, A.C.; Attanoos, R.; von der Thusen, J.H.; Tsao, M.-S.; Chang, N.; De Perrot, M.; Dacic, S. Malignant Mesothelioma in Situ: Morphologic Features and Clinical Outcome. Mod. Pathol. 2020, 33, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minami, K.; Jimbo, N.; Tanaka, Y.; Hokka, D.; Miyamoto, Y.; Itoh, T.; Maniwa, Y. Malignant Mesothelioma in Situ Diagnosed by Methylthioadenosine Phosphorylase Loss and Homozygous Deletion of CDKN2A: A Case Report. Virchows Arch. 2020, 476, 469–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soini, Y.; Kinnula, V.; Kahlos, K.; Pääkkö, P. Claudins in Differential Diagnosis between Mesothelioma and Metastatic Adenocarcinoma of the Pleura. J. Clin. Pathol. 2006, 59, 250–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, V.Y.; Cibas, E.S.; Pinkus, G.S. Claudin-4 Immunohistochemistry Is Highly Effective in Distinguishing Adenocarcinoma from Malignant Mesothelioma in Effusion Cytology. Cancer Cytopathol. 2014, 122, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Borczuk, A.C.; Siddiqui, M.T. Utility of Claudin-4 versus BerEP4 and B72.3 in Pleural Fluids with Metastatic Lung Adenocarcinoma. J. Am. Soc. Cytopathol. 2020, 9, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ang, P.P.; Tan, G.C.; Karim, N.; Wong, Y.P. Diagnostic Value of the EZH2 Immunomarker in Malignant Effusion Cytology. Acta Cytol. 2019, 64, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bott, M.; Brevet, M.; Taylor, B.S.; Shimizu, S.; Ito, T.; Wang, L.; Creaney, J.; Lake, R.A.; Zakowski, M.F.; Reva, B.; et al. The Nuclear Deubiquitinase BAP1 Is Commonly Inactivated by Somatic Mutations and 3p21.1 Losses in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Nat. Genet. 2011, 43, 668–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.C.; Pyott, S.; Rodriguez, S.; Cindric, A.; Carr, A.; Michelsen, C.; Thompson, K.; Tse, C.H.; Gown, A.M.; Churg, A. BAP1 Immunohistochemistry and P16 FISH in the Diagnosis of Sarcomatous and Desmoplastic Mesotheliomas. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2016, 40, 714–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaco, S.E.; Shuai, Y.; Bansal, M.; Krasinskas, A.M.; Dacic, S. The Diagnostic Utility of P16 FISH and GLUT-1 Immunohistochemical Analysis in Mesothelial Proliferations. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2011, 135, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinozaki-Ushiku, A.; Ushiku, T.; Morita, S.; Anraku, M.; Nakajima, J.; Fukayama, M. Diagnostic Utility of BAP1 and EZH2 Expression in Malignant Mesothelioma. Histopathology 2017, 70, 722–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, J.R.; Cheung, M.; Pei, J.; Below, J.E.; Tan, Y.; Sementino, E.; Cox, N.J.; Dogan, A.U.; Pass, H.I.; Trusa, S.; et al. Germline BAP1 Mutations Predispose to Malignant Mesothelioma. Nat. Genet. 2011, 43, 1022–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, M.; Kinoshita, Y.; Hamasaki, M.; Matsumoto, S.; Hida, T.; Oda, Y.; Iwasaki, A.; Nabeshima, K. Highly Expressed EZH2 in Combination with BAP1 and MTAP Loss, as Detected by Immunohistochemistry, Is Useful for Differentiating Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma from Reactive Mesothelial Hyperplasia. Lung Cancer 2019, 130, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgibbons, P.L.; Bradley, L.A.; Fatheree, L.A.; Alsabeh, R.; Fulton, R.S.; Goldsmith, J.D.; Haas, T.S.; Karabakhtsian, R.G.; Loykasek, P.A.; Marolt, M.J.; et al. Principles of Analytic Validation of Immunohistochemical Assays: Guideline From the College of American Pathologists Pathology and Laboratory Quality Center. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2014, 138, 1432–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauter, J.L.; Grogg, K.L.; Vrana, J.A.; Law, M.E.; Halvorson, J.L.; Henry, M.R. Young Investigator Challenge: Validation and Optimization of Immunohistochemistry Protocols for Use on Cellient Cell Block Specimens. Cancer Cytopathol. 2016, 124, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buonocore, D.J.; Konno, F.; Jungbluth, A.A.; Frosina, D.; Fayad, M.; Edelweiss, M.; Lin, O.; Rekhtman, N. CytoLyt Fixation Significantly Inhibits MIB1 Immunoreactivity Whereas Alternative Ki-67 Clone 30-9 Is Not Susceptible to the Inhibition: Critical Diagnostic Implications. Cancer Cytopathol. 2019, 127, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, D.; Nambirajan, A.; Borczuk, A.; Chen, G.; Minami, Y.; Moreira, A.L.; Motoi, N.; Papotti, M.; Rekhtman, N.; Russell, P.A.; et al. Immunocytochemistry for Predictive Biomarker Testing in Lung Cancer Cytology. Cancer Cytopathol. 2019, 127, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolff, A.C.; Hammond, M.E.H.; Hicks, D.G.; Dowsett, M.; McShane, L.M.; Allison, K.H.; Allred, D.C.; Bartlett, J.M.S.; Bilous, M.; Fitzgibbons, P.; et al. Recommendations for Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 Testing in Breast Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists Clinical Practice Guideline Update. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2014, 138, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, R.; Stawiski, E.W.; Goldstein, L.D.; Durinck, S.; De Rienzo, A.; Modrusan, Z.; Gnad, F.; Nguyen, T.T.; Jaiswal, B.S.; Chirieac, L.R.; et al. Comprehensive Genomic Analysis of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma Identifies Recurrent Mutations, Gene Fusions and Splicing Alterations. Nat. Genet. 2016, 48, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hmeljak, J.; Sanchez-Vega, F.; Hoadley, K.A.; Shih, J.; Stewart, C.; Heiman, D.; Tarpey, P.; Danilova, L.; Drill, E.; Gibb, E.A.; et al. Integrative Molecular Characterization of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 1548–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, R.R.; Nowak, A.K.; Giroux, D.J.; Eisele, M.; Rosenthal, A.; Kindler, H.; Wolf, A.; Ripley, R.T.; Billé, A.; Rice, D.; et al. The International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Mesothelioma Staging Project: Proposals for Revisions of the “T” Descriptors in the Forthcoming Ninth Edition of the TNM Classification for Pleural Mesothelioma. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2024, 19, 1310–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, A.K.; Giroux, D.J.; Eisele, M.; Rosenthal, A.; Bille, A.; Gill, R.R.; Kindler, H.L.; Pass, H.I.; Rice, D.; Ripley, R.T.; et al. The International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Pleural Mesothelioma Staging Project: Proposal for Revision of the TNM Stage Groupings in the Forthcoming (Ninth) Edition of the TNM Classification for Pleural Mesothelioma. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2024, 19, 1339–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibby, A.C.; Williams, K.; Smith, S.; Bhatt, N.; Maskell, N.A. What Is the Role of a Specialist Regional Mesothelioma Multidisciplinary Team Meeting? A Service Evaluation of One Tertiary Referral Centre in the UK. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e012092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hylebos, M.; Van Camp, G.; van Meerbeeck, J.P.; Op de Beeck, K. The Genetic Landscape of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: Results from Massively Parallel Sequencing. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2016, 11, 1615–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creaney, J.; Robinson, B.W.S. Malignant Mesothelioma Biomarkers: From Discovery to Use in Clinical Practice for Diagnosis, Monitoring, Screening, and Treatment. Chest 2017, 152, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parekh, V.S.; Jacobs, M.A. Deep Learning and Radiomics in Precision Medicine. Expert Rev. Precis. Med. Drug Dev. 2019, 4, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, A. Predicting Cancer Using Supervised Machine Learning: Mesothelioma. Technol. Health Care 2021, 29, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, A.C.; Anderson, O.; Cowell, G.W.; Weir, A.J.; Voisey, J.P.; Evison, M.; Tsim, S.; Goatman, K.A.; Blyth, K.G. Fully Automated Volumetric Measurement of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma by Deep Learning AI: Validation and Comparison with Modified RECIST Response Criteria. Thorax 2022, 77, 1251–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ram, M.; Afrash, M.R.; Moulaei, K.; Esmaeeli, E.; Khorashadizadeh, M.S.; Garavand, A.; Amiri, P.; Sabahi, A. Predicting Mesothelioma Using Artificial Intelligence: A Scoping Review of Common Models and Applications. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2025, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roche, J.J.; Seyedshahi, F.; Rakovic, K.; Thu, A.W.; Le Quesne, J.; Blyth, K.G. Current and Future Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Lung Cancer and Mesothelioma. Thorax 2025, 80, 957–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cai, B.; Wang, B.; Lv, Y.; He, W.; Xie, X.; Hou, D. Differentiating Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma and Metastatic Pleural Disease Based on a Machine Learning Model with Primary CT Signs: A Multicentre Study. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmundsson, E.; Straus, C.M.; Armato, S.G. Deep Convolutional Neural Networks for the Automated Segmentation of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma on Computed Tomography Scans. J. Med. Imaging 2018, 5, 034503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastwood, M.; Marc, S.T.; Gao, X.; Sailem, H.; Offman, J.; Karteris, E.; Fernandez, A.M.; Jonigk, D.; Cookson, W.; Moffatt, M.; et al. Malignant Mesothelioma Subtyping via Sampling Driven Multiple Instance Prediction on Tissue Image and Cell Morphology Data. Artif. Intell. Med. 2023, 143, 102628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenouda, M.; Gudmundsson, E.; Li, F.; Straus, C.M.; Kindler, H.L.; Dudek, A.Z.; Stinchcombe, T.; Wang, X.; Starkey, A.; Armato Iii, S.G. Convolutional Neural Networks for Segmentation of Pleural Mesothelioma: Analysis of Probability Map Thresholds (CALGB 30901, Alliance). J. Imaging Inf. Med. 2025, 38, 967–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamote, K.; Brinkman, P.; Vandermeersch, L.; Vynck, M.; Sterk, P.J.; Van Langenhove, H.; Thas, O.; Van Cleemput, J.; Nackaerts, K.; van Meerbeeck, J.P. Breath Analysis by Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry and Electronic Nose to Screen for Pleural Mesothelioma: A Cross-Sectional Case-Control Study. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 91593–91602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, E.A.; Thomas, P.S.; Stone, E.; Lewis, C.; Yates, D.H. A Breath Test for Malignant Mesothelioma Using an Electronic Nose. Eur. Respir. J. 2012, 40, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragonieri, S.; van der Schee, M.P.; Massaro, T.; Schiavulli, N.; Brinkman, P.; Pinca, A.; Carratú, P.; Spanevello, A.; Resta, O.; Musti, M.; et al. An Electronic Nose Distinguishes Exhaled Breath of Patients with Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma from Controls. Lung Cancer 2012, 75, 326–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusselmans, L.; Arnouts, L.; Millevert, C.; Vandersnickt, J.; van Meerbeeck, J.P.; Lamote, K. Breath Analysis as a Diagnostic and Screening Tool for Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: A Systematic Review. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2018, 7, 520–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L. Screening and Biosensor-Based Approaches for Lung Cancer Detection. Sensors 2017, 17, 2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.-S.; Lee, M.-R.; Hwangbo, Y. Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms Among Patients with Asbestos-Related Diseases in Korea. Toxics 2025, 13, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzoi, I.G.; Sauta, M.D.; De Luca, A.; Barbagli, F.; Granieri, A. Psychological Interventions for Mesothelioma Patients and Their Caregivers: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2024, 68, e347–e355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prusak, A.; van der Zwan, J.M.; Aarts, M.J.; Arber, A.; Cornelissen, R.; Burgers, S.; Duijts, S.F.A. The Psychosocial Impact of Living with Mesothelioma: Experiences and Needs of Patients and Their Carers Regarding Supportive Care. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2021, 30, e13498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, L.J.; Same, A.; Peddle-McIntyre, C.J.; Sidhu, C.; Fitzgerald, D.; Tan, A.L.; Carey, R.N.; Wilson, C.; Lee, Y.C.G. Psychosocial Needs of People Living With Pleural Mesothelioma and Family Carers: A Mixed Methods Study. Psychooncology 2024, 33, e70031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchi, L.G.; Aliprandi, M.; De Vincenzo, F.; Perrino, M.; Cordua, N.; Borea, F.; Bertocchi, A.; Federico, A.; Marulli, G.; Santoro, A.; et al. Perioperative Treatments in Pleural Mesothelioma: State of the Art and Future Directions. Cancers 2025, 17, 3199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofianidi, A.A.; Syrigos, N.K.; Blyth, K.G.; Charpidou, A.; Vathiotis, I.A. Breaking Through: Immunotherapy Innovations in Pleural Mesothelioma. Clin. Lung Cancer 2025, 26, 458–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baas, P.; Scherpereel, A.; Nowak, A.K.; Fujimoto, N.; Peters, S.; Tsao, A.S.; Mansfield, A.S.; Popat, S.; Jahan, T.; Antonia, S.; et al. First-Line Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in Unresectable Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma (CheckMate 743): A Multicentre, Randomised, Open-Label, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet 2021, 397, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Histotype | Markers |

|---|---|

| Epithelioid malignant pleural mesothelioma | calretinin/WT1/CK5/CK6/D2-40 (≥2 strongly positive); BAP1 loss, MTAP loss, p16/CDKN2A homozygous deletion, GLUT-1, membranous EMA |

| Lung adenocarcinoma | TTF-1/Napsin A/Claudin-4/MOC-31/Ber-EP4 and CEA positive; mesothelial markers negative or focal; BAP1/MTAP retained, no p16 homozygous deletion, GLUT-1 variable |

| Metastatic breast carcinoma | ER/PR/GATA3/mammaglobin/GCDFP-15 positive; mesothelial markers negative; no p16 homozygous deletion; BAP1/MTAP retained |

| Reactive mesothelial proliferation | mesothelial markers are positive; BAP1 and MTAP retained, no p16 homozygous deletion, GLUT-1 negative/weak, low Ki-67 |

| Sarcomatoid malignant pleural mesothelioma | keratin-positive, usually mesothelial markers negative, lineage markers (p40/p63, TTF-1, etc.) may help; BAP1 often retained |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fantin, A.; Castaldo, N.; Crisafulli, E.; Sartori, G.; Patrucco, F.; Grosu, H.B.; Vailati, P.; Morana, G.; Patruno, V.; Kette, S.; et al. Pleural Mesothelioma Diagnosis for the Pulmonologist: Steps Along the Way. Cancers 2025, 17, 3866. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233866

Fantin A, Castaldo N, Crisafulli E, Sartori G, Patrucco F, Grosu HB, Vailati P, Morana G, Patruno V, Kette S, et al. Pleural Mesothelioma Diagnosis for the Pulmonologist: Steps Along the Way. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3866. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233866

Chicago/Turabian StyleFantin, Alberto, Nadia Castaldo, Ernesto Crisafulli, Giulia Sartori, Filippo Patrucco, Horiana B. Grosu, Paolo Vailati, Giuseppe Morana, Vincenzo Patruno, Stefano Kette, and et al. 2025. "Pleural Mesothelioma Diagnosis for the Pulmonologist: Steps Along the Way" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3866. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233866

APA StyleFantin, A., Castaldo, N., Crisafulli, E., Sartori, G., Patrucco, F., Grosu, H. B., Vailati, P., Morana, G., Patruno, V., Kette, S., Aujayeb, A., & Rozman, A. (2025). Pleural Mesothelioma Diagnosis for the Pulmonologist: Steps Along the Way. Cancers, 17(23), 3866. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233866