Radiation-Induced Immune Responses from the Tumor Microenvironment to Systemic Immunity

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

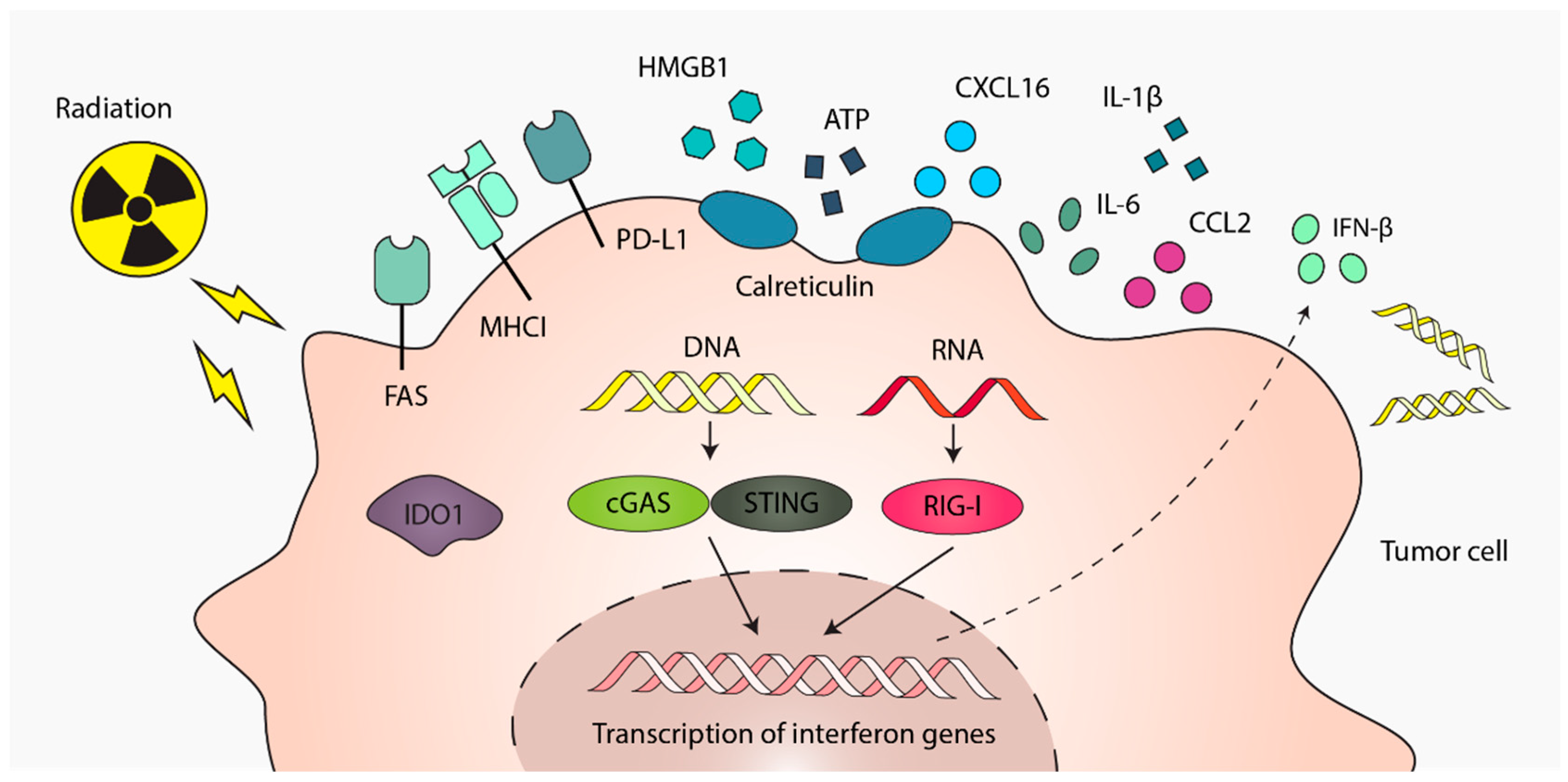

2. Radiotherapy-Induced Immune Signals from Tumor Cells

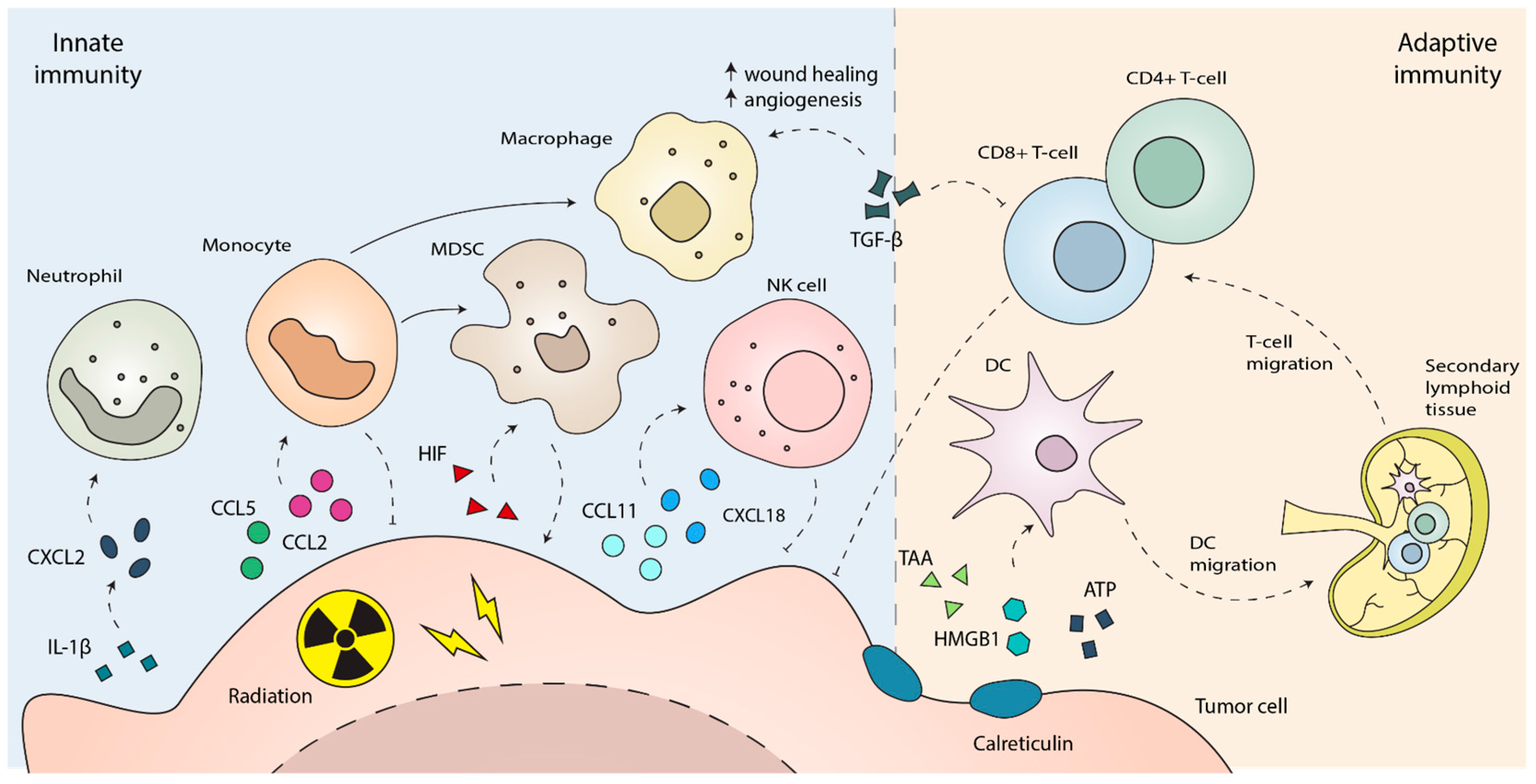

3. The Innate Immune Response to Radiotherapy

4. The Adaptive Immune Response to Radiotherapy

5. Systemic and Off-Target Immunomodulation by Radiotherapy

6. Future Perspectives

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AREG | Amphiregulin |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| ATR | Ataxia-Telangiectasia Mutated and Rad3-Related |

| cGAS | Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase |

| CSF1 | Colony stimulating factor 1 |

| DAMPs | Damage-associated molecular patterns |

| DCs | Dendritic cells |

| dsDNA | Double stranded-DNA |

| FAS | Fas cell surface death receptor |

| FLT3L | FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand |

| GM-CSF | Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

| HIF | Hypoxia-inducible factor |

| HMGB1 | High mobility group box 1 protein |

| ICB | Immune checkpoint blockade |

| ICD | Immunogenic cell death |

| IDO-1 | Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 |

| IFN-I | Type 1 interferon |

| MDSCs | Myeloid-derived suppressor cells |

| MHCI | Major histocompatibility complex I |

| NK | Natural killer |

| NLRP3 | NOD-, LRR- and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 |

| PD-1 | Programmed cell death protein 1 |

| PD-L1 | Programmed death-ligand 1 |

| PGE | Prostaglandin E2 |

| RIG1 | Retinoic acid-inducible gene I |

| SIRPα | Signal regulatory protein α |

| STING | Stimulator of interferon genes |

| TGFβ | Transforming growth factor β |

| TLR4 | Toll-like receptor 4 |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| TNF | Tumor necrosis factor |

| Treg | Regulatory T-cell |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

References

- Wang, L.; Lynch, C.; Pitroda, S.P.; Piffkó, A.; Yang, K.; Huser, A.K.; Liang, H.L.; Weichselbaum, R.R. Radiotherapy and Immunology. J. Exp. Med. 2024, 221, e20232101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandmaier, A.; Formenti, S.C. The Impact of Radiation Therapy on Innate and Adaptive Tumor Immunity. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 2020, 30, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donlon, N.E.; Power, R.; Hayes, C.; Reynolds, J.V.; Lysaght, J. Radiotherapy, Immunotherapy, and the Tumour Microenvironment: Turning an Immunosuppressive Milieu into a Therapeutic Opportunity. Cancer Lett. 2021, 502, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesenko, T.; Bosnjak, M.; Markelc, B.; Sersa, G.; Znidar, K.; Heller, L.; Cemazar, M. Radiation Induced Upregulation of DNA Sensing Pathways Is Cell-Type Dependent and Can Mediate the Off-Target Effects. Cancers 2020, 12, 3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, T.; Kobayashi, J.; Saitoh, T.; Maruyama, K.; Ishii, K.J.; Barber, G.N.; Komatsu, K.; Akira, S.; Kawai, T. DNA Damage Sensor MRE11 Recognizes Cytosolic Double-Stranded DNA and Induces Type I Interferon by Regulating STING Trafficking. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 2969–2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranoa, D.R.E.; Parekh, A.D.; Pitroda, S.P.; Huang, X.; Darga, T.; Wong, A.C.; Huang, L.; Andrade, J.; Staley, J.P.; Satoh, T.; et al. Cancer Therapies Activate RIG-I-like Receptor Pathway through Endogenous Non-Coding RNAs. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 26496–26515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Kageyama, S.-I.; Yamashita, R.; Tanaka, K.; Okumura, M.; Motegi, A.; Hojo, H.; Nakamura, M.; Hirata, H.; Sunakawa, H.; et al. Transposable Elements Potentiate Radiotherapy-Induced Cellular Immune Reactions via RIG-I-Mediated Virus-Sensing Pathways. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reits, E.A.; Hodge, J.W.; Herberts, C.A.; Groothuis, T.A.; Chakraborty, M.; K.Wansley, E.; Camphausen, K.; Luiten, R.M.; de Ru, A.H.; Neijssen, J.; et al. Radiation Modulates the Peptide Repertoire, Enhances MHC Class I Expression, and Induces Successful Antitumor Immunotherapy. J. Exp. Med. 2006, 203, 1259–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.-H.; Lei, Z.; Yang, H.-N.; Tang, Z.; Yang, M.-Q.; Wang, Y.; Sui, J.-D.; Wu, Y.-Z. Radiation-Induced PD-L1 Expression in Tumor and Its Microenvironment Facilitates Cancer-Immune Escape: A Narrative Review. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, M.; Abrams, S.I.; Camphausen, K.; Liu, K.; Scott, T.; Coleman, C.N.; Hodge, J.W. Irradiation of Tumor Cells Up-Regulates Fas and Enhances CTL Lytic Activity and CTL Adoptive Immunotherapy. J. Immunol. 2003, 170, 6338–6347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmgaard, R.B.; Zamarin, D.; Li, Y.; Gasmi, B.; Munn, D.H.; Allison, J.P.; Merghoub, T.; Wolchok, J.D. Tumor-Expressed IDO Recruits and Activates MDSCs in a Treg-Dependent Manner. Cell Rep. 2015, 13, 412–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Liang, H.; Xu, M.; Yang, X.; Burnette, B.; Arina, A.; Li, X.-D.; Mauceri, H.; Beckett, M.; Darga, T.; et al. STING-Dependent Cytosolic DNA Sensing Promotes Radiation-Induced Type I Interferon-Dependent Antitumor Immunity in Immunogenic Tumors. Immunity 2014, 41, 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gameiro, S.R.; Jammed, M.L.; Wattenberg, M.M.; Tsang, K.Y.; Ferrone, S.; Hodge, J.W. Radiation-Induced Immunogenic Modulation of Tumor Enhances Antigen Processing and Calreticulin Exposure, Resulting in Enhanced T-Cell Killing. Oncotarget 2013, 5, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apetoh, L.; Ghiringhelli, F.; Tesniere, A.; Obeid, M.; Ortiz, C.; Criollo, A.; Mignot, G.; Maiuri, M.C.; Ullrich, E.; Saulnier, P.; et al. Toll-like Receptor 4–Dependent Contribution of the Immune System to Anticancer Chemotherapy and Radiotherapy. Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 1050–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeid, M.; Panaretakis, T.; Joza, N.; Tufi, R.; Tesniere, A.; van Endert, P.; Zitvogel, L.; Kroemer, G. Calreticulin Exposure Is Required for the Immunogenicity of γ-Irradiation and UVC Light-Induced Apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2007, 14, 1848–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiringhelli, F.; Apetoh, L.; Tesniere, A.; Aymeric, L.; Ma, Y.; Ortiz, C.; Vermaelen, K.; Panaretakis, T.; Mignot, G.; Ullrich, E.; et al. Activation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome in Dendritic Cells Induces IL-1β–Dependent Adaptive Immunity against Tumors. Nat. Med. 2009, 15, 1170–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cytlak, U.M.; Dyer, D.P.; Honeychurch, J.; Williams, K.J.; Travis, M.A.; Illidge, T.M. Immunomodulation by Radiotherapy in Tumour Control and Normal Tissue Toxicity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2022, 22, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, K.A.; Belt, B.A.; Figueroa, N.M.; Murthy, A.; Patel, A.; Kim, M.; Lord, E.M.; Linehan, D.C.; Gerber, S.A. Increasing the Efficacy of Radiotherapy by Modulating the CCR2/CCR5 Chemokine Axes. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 86522–86535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumura, S.; Wang, B.; Kawashima, N.; Braunstein, S.; Badura, M.; Cameron, T.O.; Babb, J.S.; Schneider, R.J.; Formenti, S.C.; Dustin, M.L.; et al. Radiation-Induced CXCL16 Release by Breast Cancer Cells Attracts Effector T Cells. J. Immunol. 2008, 181, 3099–3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanpouille-Box, C.; Alard, A.; Aryankalayil, M.J.; Sarfraz, Y.; Diamond, J.M.; Schneider, R.J.; Inghirami, G.; Coleman, C.N.; Formenti, S.C.; Demaria, S. DNA Exonuclease Trex1 Regulates Radiotherapy-Induced Tumour Immunogenicity. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, J.-Z.; Zhu, Y.-Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, L.-L.; Hu, L.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Q.-Y. Abscopal Effects of Local Radiotherapy Are Dependent on Tumor Immunogenicity. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 690188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T.; Liu, L.; Jiang, W.; Zhou, R. DAMP-Sensing Receptors in Sterile Inflammation and Inflammatory Diseases. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guipaud, O.; Jaillet, C.; Clément-Colmou, K.; François, A.; Supiot, S.; Milliat, F. The Importance of the Vascular Endothelial Barrier in the Immune-Inflammatory Response Induced by Radiotherapy. Br. J. Radiol. 2018, 91, 20170762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raymakers, L.; Demmers, T.J.; Meijer, G.J.; Molenaar, I.Q.; van Santvoort, H.C.; Intven, M.P.W.; Leusen, J.H.W.; Olofsen, P.A.; Daamen, L.A. The Effect of Radiation Treatment of Solid Tumors on Neutrophil Infiltration and Function: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2024, 120, 845–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Mulvaney, O.; Salcedo, E.; Manna, S.; Zhu, J.Z.; Wang, T.; Ahn, C.; Pop, L.M.; Hannan, R. Radiation-Induced Innate Neutrophil Response in Tumor Is Mediated by the CXCLs/CXCR2 Axis. Cancers 2023, 15, 5686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, A.M.; Johnston, C.J.; Williams, J.P.; Finkelstein, J.N. Role of Infiltrating Monocytes in the Development of Radiation-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis. Radiat. Res. 2018, 189, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadepalli, S.; Clements, D.R.; Saravanan, S.; Hornero, R.A.; Lüdtke, A.; Blackmore, B.; Paulo, J.A.; Gottfried-Blackmore, A.; Seong, D.; Park, S.; et al. Rapid Recruitment and IFN-I–Mediated Activation of Monocytes Dictate Focal Radiotherapy Efficacy. Sci. Immunol. 2023, 8, eadd7446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadepalli, S.; Clements, D.R.; Raquer-McKay, H.M.; Lüdtke, A.; Saravanan, S.; Seong, D.; Vitek, L.; Richards, C.M.; Carette, J.E.; Mack, M.; et al. CD301b+ Monocyte-Derived Dendritic Cells Mediate Resistance to Radiotherapy. J. Exp. Med. 2025, 222, e20231717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Escamilla, J.; Mok, S.; David, J.; Priceman, S.; West, B.; Bollag, G.; McBride, W.; Wu, L. CSF1R Signaling Blockade Stanches Tumor-Infiltrating Myeloid Cells and Improves the Efficacy of Radiotherapy in Prostate Cancer. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 2782–2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Deng, L.; Hou, Y.; Meng, X.; Huang, X.; Rao, E.; Zheng, W.; Mauceri, H.; Mack, M.; Xu, M.; et al. Host STING-Dependent MDSC Mobilization Drives Extrinsic Radiation Resistance. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalbasi, A.; Komar, C.; Tooker, G.M.; Liu, M.; Lee, J.W.; Gladney, W.L.; Ben-Josef, E.; Beatty, G.L. Tumor-Derived CCL2 Mediates Resistance to Radiotherapy in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergerud, K.M.B.; Berkseth, M.; Pardoll, D.M.; Ganguly, S.; Kleinberg, L.R.; Lawrence, J.; Odde, D.J.; Largaespada, D.A.; Terezakis, S.A.; Sloan, L. Radiation Therapy and Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells: Breaking Down Their Cancerous Partnership. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2024, 119, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrand-Rosenberg, S.; Horn, L.A.; Ciavattone, N.G. Radiotherapy Both Promotes and Inhibits Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cell Function: Novel Strategies for Preventing the Tumor-Protective Effects of Radiotherapy. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.-N.; Luo, W.; Sun, C.; Jin, Z.; Zeng, X.; Alexander, P.B.; Gong, Z.; Xia, X.; Ding, X.; Xu, S.; et al. Radiation-Induced Eosinophils Improve Cytotoxic T Lymphocyte Recruitment and Response to Immunotherapy. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabc7609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walle, T.; Kraske, J.A.; Liao, B.; Lenoir, B.; Timke, C.; Halbach, E.v.B.U.; Tran, F.; Griebel, P.; Albrecht, D.; Ahmed, A.; et al. Radiotherapy Orchestrates Natural Killer Cell Dependent Antitumor Immune Responses through CXCL8. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabh4050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickett, T.E.; Knitz, M.; Darragh, L.B.; Bhatia, S.; Court, B.V.; Gadwa, J.; Bhuvane, S.; Piper, M.; Nguyen, D.; Tu, H.; et al. FLT3L Release by NK Cells Enhances Response to Radioimmunotherapy in Preclinical Models of HNSCC. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 6235–6249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, W.; Ling, S.; Cao, Y.; Shao, C.; Sun, X. Combined Use of NK Cells and Radiotherapy in the Treatment of Solid Tumors. Front. Immunol. 2024, 14, 1306534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uong, T.N.T.; Yoon, M.; Chung, I.-J.; Nam, T.-K.; Ahn, S.-J.; Jeong, J.-U.; Song, J.-Y.; Kim, Y.-H.; Nguyen, H.P.Q.; Cho, D.; et al. Direct Tumor Irradiation Potentiates Adoptive NK Cell Targeting Against Parental and Stemlike Cancer in Human Liver Cancer Models. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2024, 119, 234–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.; Liu, Z.; Dong, X.; Wang, K.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, F.; Chen, Y.; Ling, J.; Guo, Y.; et al. Radiotherapy Enhances the Anti-Tumor Effect of CAR-NK Cells for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilones, K.A.; Charpentier, M.; Garcia-Martinez, E.; Daviaud, C.; Kraynak, J.; Aryankalayil, J.; Formenti, S.C.; Demaria, S. Radiotherapy Cooperates with IL15 to Induce Antitumor Immune Responses. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2020, 8, 1054–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Hannan, R.; Fu, Y.-X. Type I IFN Activating Type I Dendritic Cells for Antitumor Immunity. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 3818–3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patin, E.C.; Dillon, M.T.; Nenclares, P.; Grove, L.; Soliman, H.; Leslie, I.; Northcote, D.; Bozhanova, G.; Crespo-Rodriguez, E.; Baldock, H.; et al. Harnessing Radiotherapy-Induced NK-Cell Activity by Combining DNA Damage–Response Inhibition and Immune Checkpoint Blockade. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e004306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, S.; Leader, A.M.; Merad, M. MDSC: Markers, Development, States, and Unaddressed Complexity. Immunity 2021, 54, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, S.K.; Mantovani, A. Macrophage Plasticity and Interaction with Lymphocyte Subsets: Cancer as a Paradigm. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 889–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhood, B.; Khodamoradi, E.; Hoseini-Ghahfarokhi, M.; Motevaseli, E.; Mirtavoos-Mahyari, H.; Musa, A.E.; Najafi, M. TGF-β in Radiotherapy: Mechanisms of Tumor Resistance and Normal Tissues Injury. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 155, 104745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridlender, Z.G.; Sun, J.; Kim, S.; Kapoor, V.; Cheng, G.; Ling, L.; Worthen, G.S.; Albelda, S.M. Polarization of Tumor-Associated Neutrophil Phenotype by TGF-β: “N1” versus “N2” TAN. Cancer Cell 2009, 16, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanpouille-Box, C.; Diamond, J.M.; Pilones, K.A.; Zavadil, J.; Babb, J.S.; Formenti, S.C.; Barcellos-Hoff, M.H.; Demaria, S. TGFβ Is a Master Regulator of Radiation Therapy-Induced Antitumor Immunity. Cancer Res. 2015, 75, 2232–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klug, F.; Prakash, H.; Huber, P.E.; Seibel, T.; Bender, N.; Halama, N.; Pfirschke, C.; Voss, R.H.; Timke, C.; Umansky, L.; et al. Low-Dose Irradiation Programs Macrophage Differentiation to an iNOS+/M1 Phenotype That Orchestrates Effective T Cell Immunotherapy. Cancer Cell 2013, 24, 589–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiga, Y.; Drainas, A.P.; Baron, M.; Bhattacharya, D.; Barkal, A.A.; Ahrari, Y.; Mancusi, R.; Ross, J.B.; Takahashi, N.; Thomas, A.; et al. Radiotherapy in Combination with CD47 Blockade Elicits a Macrophage-Mediated Abscopal Effect. Nat. Cancer 2022, 3, 1351–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeshima, T.; Pop, L.M.; Laine, A.; Iyengar, P.; Vitetta, E.S.; Hannan, R. Key Role for Neutrophils in Radiation-Induced Antitumor Immune Responses: Potentiation with G-CSF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 11300–11305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, T.C.; Bambina, S.; Alice, A.F.; Kramer, G.F.; Medler, T.R.; Baird, J.R.; Broz, M.L.; Tormoen, G.W.; Troesch, V.; Crittenden, M.R.; et al. Dendritic Cell Maturation Defines Immunological Responsiveness of Tumors to Radiation Therapy. J. Immunol. 2020, 204, 3416–3424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.P.; Alice, A.; Crittenden, M.R.; Gough, M.J. The Role of Dendritic Cells in Radiation-Induced Immune Responses. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2023, 378, 61–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crittenden, M.R.; Baird, J.; Friedman, D.; Savage, T.; Uhde, L.; Alice, A.; Cottam, B.; Young, K.; Newell, P.; Nguyen, C.; et al. Mertk on Tumor Macrophages Is a Therapeutic Target to Prevent Tumor Recurrence Following Radiation Therapy. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 78653–78666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanzavecchia, A.; Sallusto, F. Dynamics of T Lymphocyte Responses: Intermediates, Effectors, and Memory Cells. Science 2000, 290, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.Y.H.; Gerber, S.A.; Murphy, S.P.; Lord, E.M. Type I Interferons Induced by Radiation Therapy Mediate Recruitment and Effector Function of CD8+ T Cells. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2014, 63, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, S.-R.; Fuertes, M.B.; Corrales, L.; Spranger, S.; Furdyna, M.J.; Leung, M.Y.K.; Duggan, R.; Wang, Y.; Barber, G.N.; Fitzgerald, K.A.; et al. STING-Dependent Cytosolic DNA Sensing Mediates Innate Immune Recognition of Immunogenic Tumors. Immunity 2014, 41, 830–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, S.M.; Benci, J.L.; Irianto, J.; Discher, D.E.; Minn, A.J.; Greenberg, R.A. Mitotic Progression Following DNA Damage Enables Pattern Recognition within Micronuclei. Nature 2017, 548, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, R.C.-E.; Krishnan, S.; Wu, R.-C.; Boda, A.R.; Liu, A.; Winkler, M.; Hsu, W.-H.; Lin, S.H.; Hung, M.-C.; Chan, L.-C.; et al. ATR-Mediated CD47 and PD-L1 up-Regulation Restricts Radiotherapy-Induced Immune Priming and Abscopal Responses in Colorectal Cancer. Sci. Immunol. 2022, 7, eabl9330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Li, F.; Liu, X.; Li, W.; Shi, W.; Liu, F.-F.; O’Sullivan, B.; He, Z.; Peng, Y.; Tan, A.-C.; et al. Caspase 3–Mediated Stimulation of Tumor Cell Repopulation during Cancer Radiotherapy. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 860–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böttcher, J.P.; Bonavita, E.; Chakravarty, P.; Blees, H.; Cabeza-Cabrerizo, M.; Sammicheli, S.; Rogers, N.C.; Sahai, E.; Zelenay, S.; e Sousa, C.R. NK Cells Stimulate Recruitment of cDC1 into the Tumor Microenvironment Promoting Cancer Immune Control. Cell 2018, 172, 1022–1037.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanpouille-Box, C.; Pilones, K.; Formenti, S.; Demaria, S. Abstract IA04: Partnership of Radiotherapy and Immunotherapy: A New Paradigm in Cancer Treatment. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2015, 3, IA04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, K.H.; Newell, P.; Cottam, B.; Friedman, D.; Savage, T.; Baird, J.R.; Akporiaye, E.; Gough, M.J.; Crittenden, M. TGFβ Inhibition Prior to Hypofractionated Radiation Enhances Efficacy in Preclinical Models. Cancer Immunol. 2014, 2, 1011–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunderson, A.J.; Yamazaki, T.; McCarty, K.; Fox, N.; Phillips, M.; Alice, A.; Blair, T.; Whiteford, M.; O’Brien, D.; Ahmad, R.; et al. TGFβ Suppresses CD8+ T Cell Expression of CXCR3 and Tumor Trafficking. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, J.; Le, T.Q.; Massarelli, E.; Hendifar, A.E.; Tuli, R. Radiation Therapy and PD-1/PD-L1 Blockade: The Clinical Development of an Evolving Anticancer Combination. J. Immunother. Cancer 2018, 6, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formenti, S.C.; Rudqvist, N.-P.; Golden, E.; Cooper, B.; Wennerberg, E.; Lhuillier, C.; Vanpouille-Box, C.; Friedman, K.; de Andrade, L.F.; Wucherpfennig, K.W.; et al. Radiotherapy Induces Responses of Lung Cancer to CTLA-4 Blockade. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1845–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mole, R.H. Whole Body Irradiation—Radiobiology or Medicine? Br. J. Radiol. 1953, 26, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuodeh, Y.; Venkat, P.; Kim, S. Systematic Review of Case Reports on the Abscopal Effect. Curr. Probl. Cancer 2016, 40, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatten, S.J.; Lehrer, E.J.; Liao, J.; Sha, C.M.; Trifiletti, D.M.; Siva, S.; McBride, S.M.; Palma, D.; Holder, S.L.; Zaorsky, N.G. A Patient-Level Data Meta-Analysis of the Abscopal Effect. Adv. Radiat. Oncol. 2022, 7, 100909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demaria, S.; Ng, B.; Devitt, M.L.; Babb, J.S.; Kawashima, N.; Liebes, L.; Formenti, S.C. Ionizing Radiation Inhibition of Distant Untreated Tumors (Abscopal Effect) Is Immune Mediated. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2004, 58, 862–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Ruiz, M.E.; Rodriguez, I.; Garasa, S.; Barbes, B.; Solorzano, J.L.; Perez-Gracia, J.L.; Labiano, S.; Sanmamed, M.F.; Azpilikueta, A.; Bolaños, E.; et al. Abscopal Effects of Radiotherapy Are Enhanced by Combined Immunostimulatory mAbs and Are Dependent on CD8 T Cells and Crosspriming. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 5994–6005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, E.B.; Chhabra, A.; Chachoua, A.; Adams, S.; Donach, M.; Fenton-Kerimian, M.; Friedman, K.; Ponzo, F.; Babb, J.S.; Goldberg, J.; et al. Local Radiotherapy and Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor to Generate Abscopal Responses in Patients with Metastatic Solid Tumours: A Proof-of-Principle Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabrinsky, E.; Macklis, J.; Bitran, J. A Review of the Abscopal Effect in the Era of Immunotherapy. Cureus 2022, 14, e29620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dong, Y.; Kong, L.; Shi, F.; Zhu, H.; Yu, J. Abscopal Effect of Radiotherapy Combined with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2018, 11, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngwa, W.; Irabor, O.C.; Schoenfeld, J.D.; Hesser, J.; Demaria, S.; Formenti, S.C. Using Immunotherapy to Boost the Abscopal Effect. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Z.; Jia, S.; Shao, C.; Shi, Y. Irradiation Induces Cancer Lung Metastasis through Activation of the cGAS–STING–CCL5 Pathway in Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; Yang, K.; Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Huang, X.; Piffkó, A.; Luo, S.Z.; Yu, X.; Rao, E.; Martinez, C.; et al. Radiotherapy Enhances Metastasis Through Immune Suppression by Inducing PD-L1 and MDSC in Distal Sites. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 1945–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piffkó, A.; Yang, K.; Panda, A.; Heide, J.; Tesak, K.; Wen, C.; Zawieracz, K.; Wang, L.; Naccasha, E.Z.; Bugno, J.; et al. Radiation-Induced Amphiregulin Drives Tumour Metastasis. Nature 2025, 643, 810–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straub, J.M.; New, J.; Hamilton, C.D.; Lominska, C.; Shnayder, Y.; Thomas, S.M. Radiation-Induced Fibrosis: Mechanisms and Implications for Therapy. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 141, 1985–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynn, T.A. Fibrotic Disease and the TH1/TH2 Paradigm. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004, 4, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, E.; Bridgeman, V.L.; Ombrato, L.; Karoutas, A.; Rabas, N.; Sewnath, C.A.N.; Vasquez, M.; Rodrigues, F.S.; Horswell, S.; Faull, P.; et al. Radiation Exposure Elicits a Neutrophil-Driven Response in Healthy Lung Tissue That Enhances Metastatic Colonization. Nat. Cancer 2022, 3, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafat, M.; Aguilera, T.A.; Vilalta, M.; Bronsart, L.L.; Soto, L.A.; von Eyben, R.; Golla, M.A.; Ahrari, Y.; Melemenidis, S.; Afghahi, A.; et al. Macrophages Promote Circulating Tumor Cell–Mediated Local Recurrence Following Radiotherapy in Immunosuppressed Patients. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 4241–4252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ando, K.; Hunter, N.; Peters, L.J. Inhibition of Artificial Lung Metastases in Mice by Pre-Irradiation of Abdomen. Br. J. Cancer 1980, 41, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, K.; Peters, L.J.; Hunter, N.; Jinnouchi, K.; Matsumoto, T. Inhibition of Artificial and Spontaneous Lung Metastases by Preirradiation of Abdomen—II. Target Organ and Mechanism. Br. J. Cancer 1983, 47, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Peng, Z.; Liu, X.; Chen, J.; Zheng, X. Role of Lung and Gut Microbiota on Lung Cancer Pathogenesis. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 147, 2177–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Cheng, Y.; Zang, D.; Zhang, M.; Li, X.; Liu, D.; Gao, B.; Zhou, H.; Sun, J.; Han, X.; et al. The Role of Gut Microbiota in Lung Cancer: From Carcinogenesis to Immunotherapy. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 720842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Levy, A.; Tian, A.-L.; Huang, X.; Cai, G.; Fidelle, M.; Rauber, C.; Ly, P.; Pizzato, E.; Sitterle, L.; et al. Low-Dose Irradiation of the Gut Improves the Efficacy of PD-L1 Blockade in Metastatic Cancer Patients. Cancer Cell 2025, 43, 361–379.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordbacheh, T.; Honeychurch, J.; Blackhall, F.; Faivre-Finn, C.; Illidge, T. Radiotherapy and Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 Combinations in Lung Cancer: Building Better Translational Research Platforms. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, H.; Okonogi, N.; Nakano, T. Rationale of Combination of Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 Antibody Therapy and Radiotherapy for Cancer Treatment. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 25, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, T.B.; Henson, R.M.; Shiao, S.L. Targeting Innate Immunity to Enhance the Efficacy of Radiation Therapy. Front. Immunol. 2019, 9, 3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paganetti, H. A Review on Lymphocyte Radiosensitivity and Its Impact on Radiotherapy. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1201500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffari-Nazari, H.; Alimohammadi, M.; Alimohammadi, R.; Rostami, E.; Bakhshandeh, M.; Webster, T.J.; Chalbatani, G.M.; Tavakkol-Afshari, J.; Jalali, S.A. Radiation Dose and Schedule Influence the Abscopal Effect in a Bilateral Murine CT26 Tumor Model. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 108, 108737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, H.; Chen, D.; Ramapriyan, R.; Verma, V.; Barsoumian, H.B.; Cushman, T.R.; Younes, A.I.; Cortez, M.A.; Erasmus, J.J.; de Groot, P.; et al. Influence of Low-Dose Radiation on Abscopal Responses in Patients Receiving High-Dose Radiation and Immunotherapy. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Hou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, H.; Sharma, A.; Zheng, W.; Wang, L.; Torres, R.; Tatebe, K.; Chmura, S.J.; et al. Suppression of Local Type I Interferon by Gut Microbiota–Derived Butyrate Impairs Antitumor Effects of Ionizing Radiation. J. Exp. Med. 2021, 218, e20201915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.-N.; Ma, Q.; Ge, Y.; Yi, C.-X.; Wei, L.-Q.; Tan, J.-C.; Chu, Q.; Li, J.-Q.; Zhang, P.; Wang, H. Microbiome Dysbiosis in Lung Cancer: From Composition to Therapy. npj Precis. Oncol. 2020, 4, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-Labrada, A.G.; Isla, D.; Artal, A.; Arias, M.; Rezusta, A.; Pardo, J.; Gálvez, E.M. The Influence of Lung Microbiota on Lung Carcinogenesis, Immunity, and Immunotherapy. Trends Cancer 2020, 6, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budden, K.F.; Gellatly, S.L.; Wood, D.L.A.; Cooper, M.A.; Morrison, M.; Hugenholtz, P.; Hansbro, P.M. Emerging Pathogenic Links between Microbiota and the Gut–Lung Axis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasanna, P.G.S.; Narayanan, D.; Hallett, K.; Bernhard, E.J.; Ahmed, M.M.; Evans, G.; Vikram, B.; Weingarten, M.; Coleman, C.N. Radioprotectors and Radiomitigators for Improving Radiation Therapy: The Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) Gateway for Accelerating Clinical Translation. Radiat. Res. 2015, 184, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakeri, K.; Narayanan, D.; Vikram, B.; Evans, G.; Coleman, C.N.; Prasanna, P.G.S. Decreasing the Toxicity of Radiation Therapy: Radioprotectors and Radiomitigators Being Developed by the National Cancer Institute Through Small Business Innovation Research Contracts. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2019, 104, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, B.; Huang, D.; Gao, F.; Yang, Y.; Wu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, G.; Dai, T.; Du, X. Mechanisms of FLASH Effect. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 995612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Png, S.; Tadepalli, S.; Graves, E.E. Radiation-Induced Immune Responses from the Tumor Microenvironment to Systemic Immunity. Cancers 2025, 17, 3849. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233849

Png S, Tadepalli S, Graves EE. Radiation-Induced Immune Responses from the Tumor Microenvironment to Systemic Immunity. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3849. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233849

Chicago/Turabian StylePng, Shaun, Sirimuvva Tadepalli, and Edward E. Graves. 2025. "Radiation-Induced Immune Responses from the Tumor Microenvironment to Systemic Immunity" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3849. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233849

APA StylePng, S., Tadepalli, S., & Graves, E. E. (2025). Radiation-Induced Immune Responses from the Tumor Microenvironment to Systemic Immunity. Cancers, 17(23), 3849. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233849