Daily Consumption of Apigenin Prevents Acute Lymphoma/Lymphoblastic Leukemia in Male C57BL/6J Mice Exposed to Space-like Radiation

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

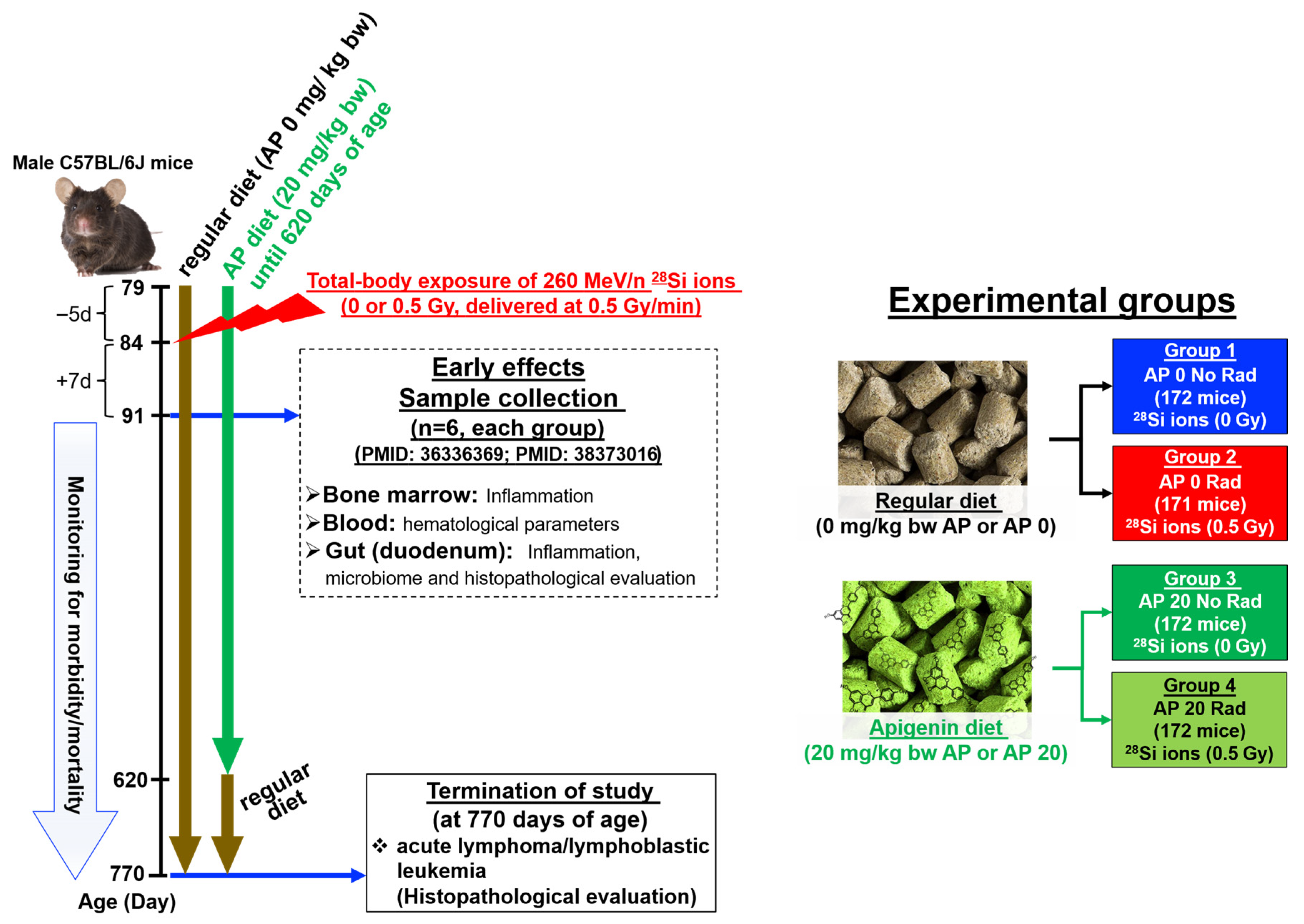

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

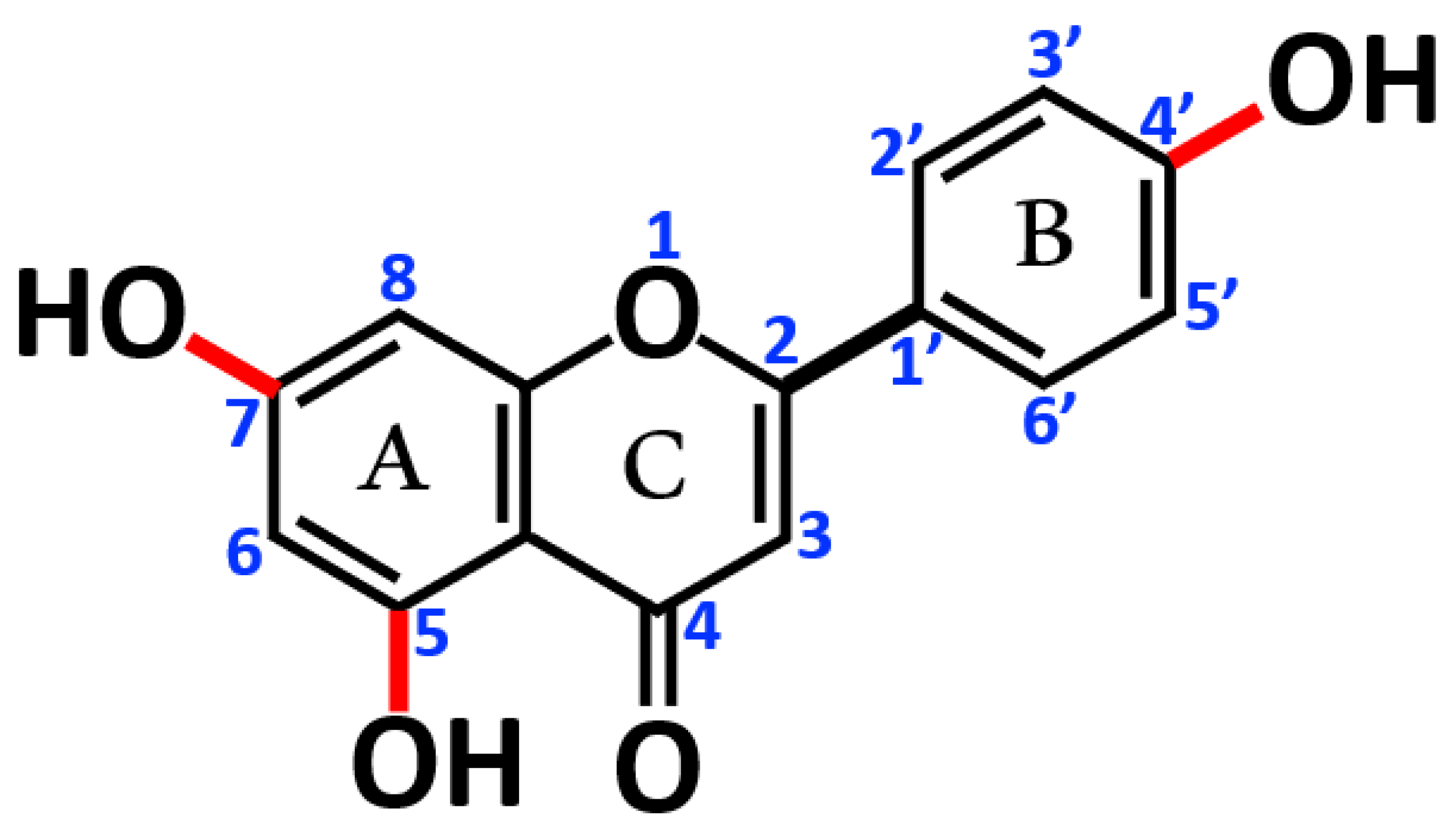

2.2. AP Diet Supplement

2.3. Whole-Body Exposure of Mice to 260 MeV/n, 28Si Ions

2.4. Statistical Analysis

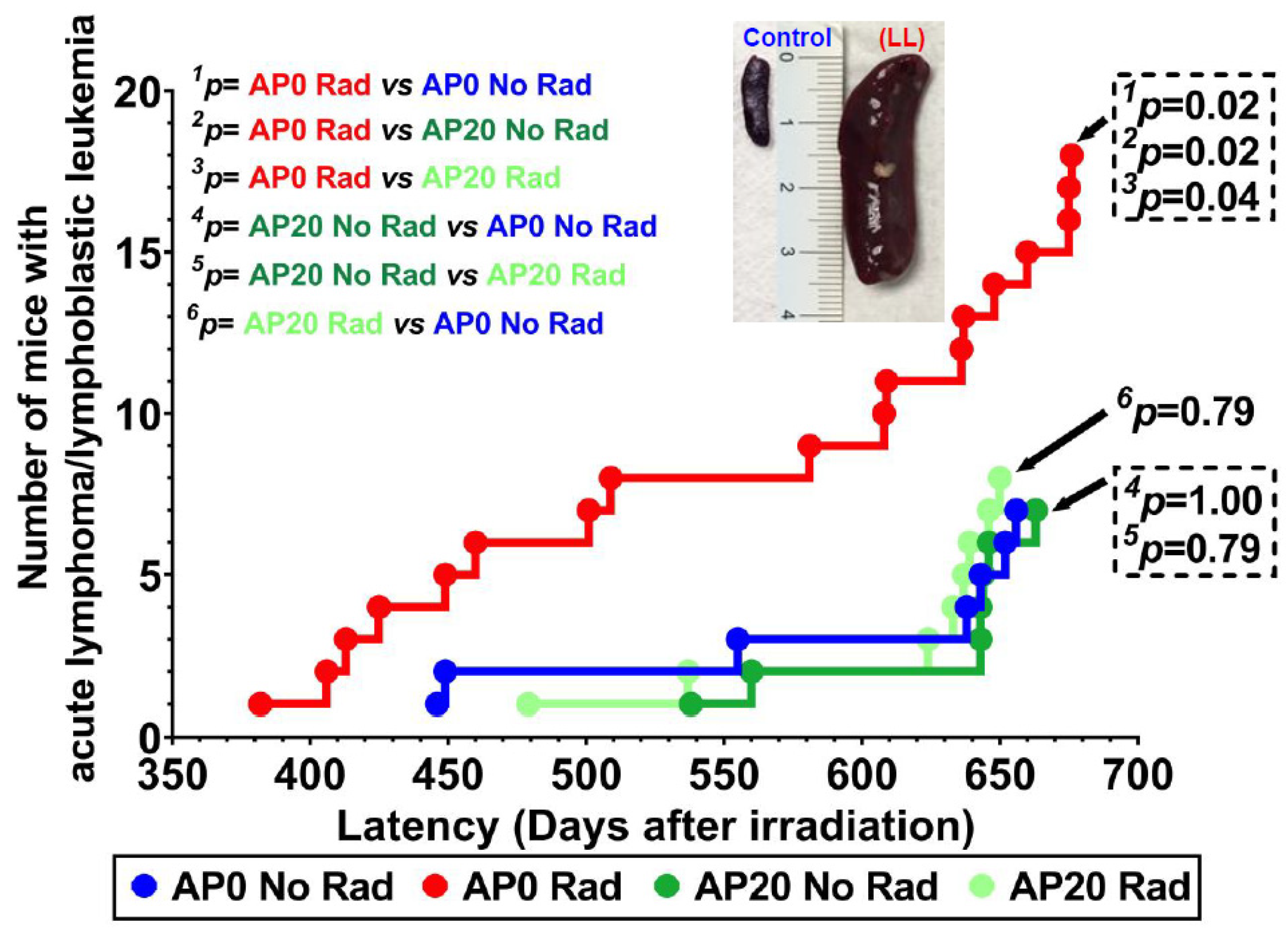

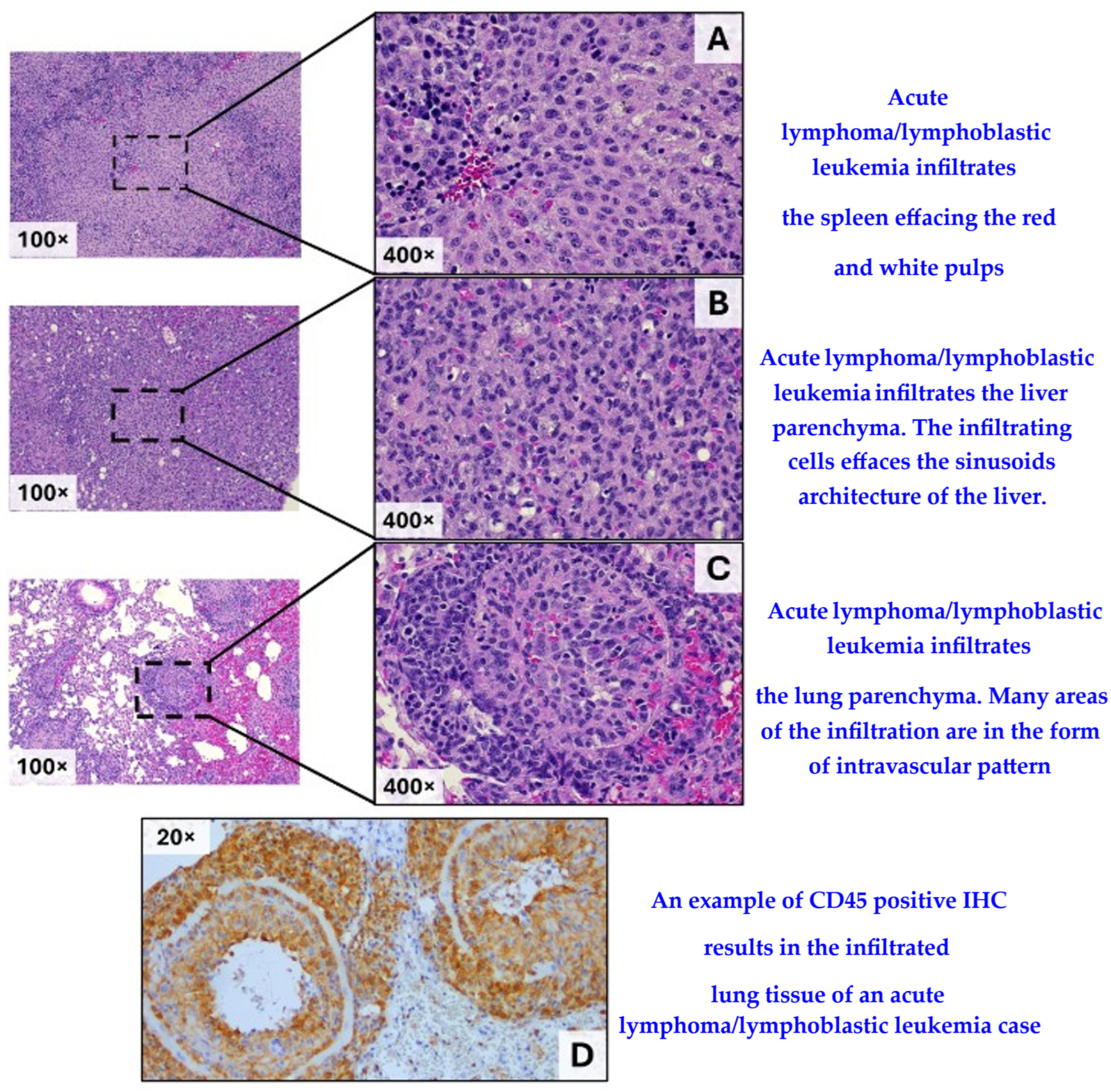

3. Results

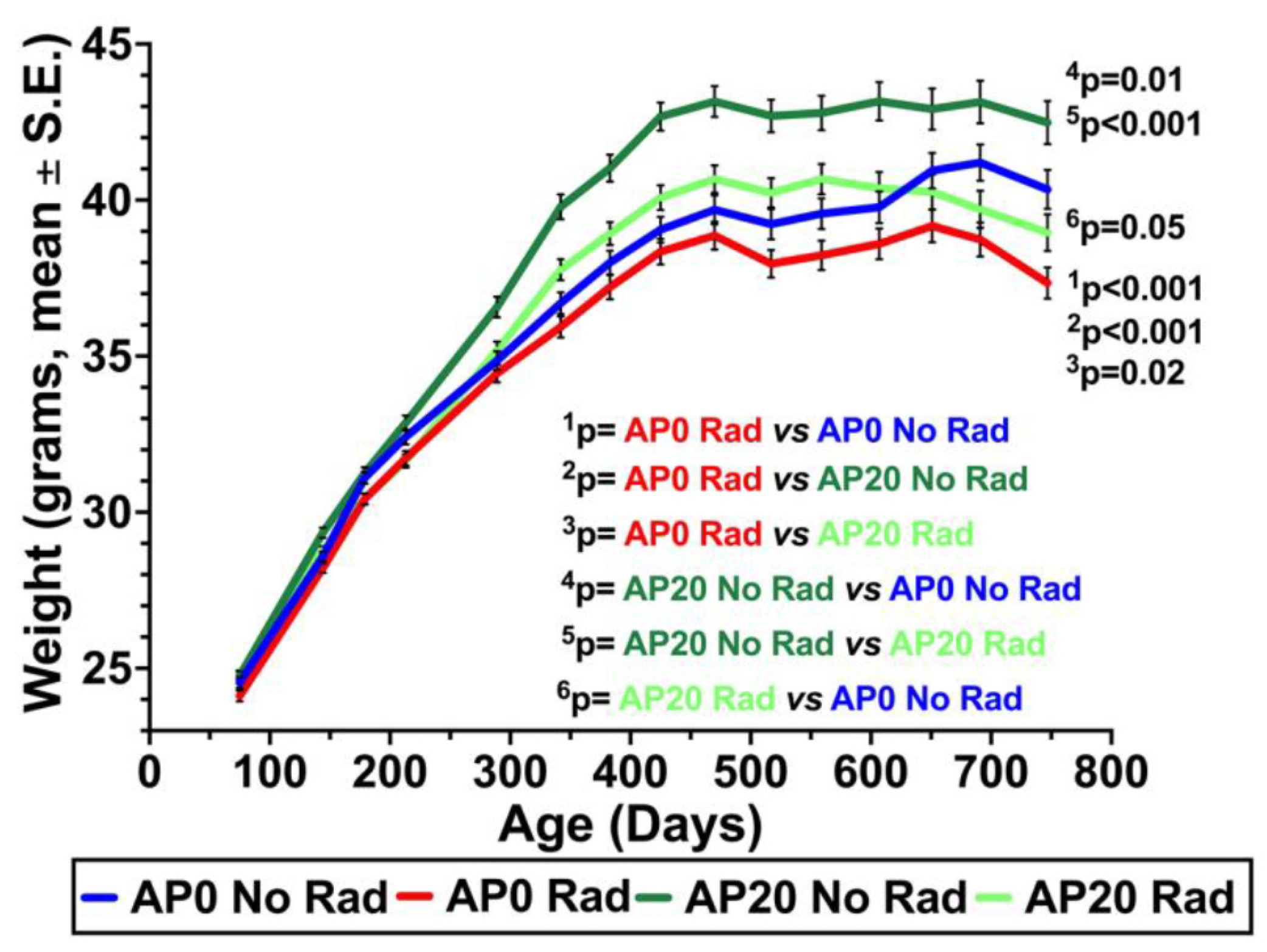

3.1. Weights of Mice

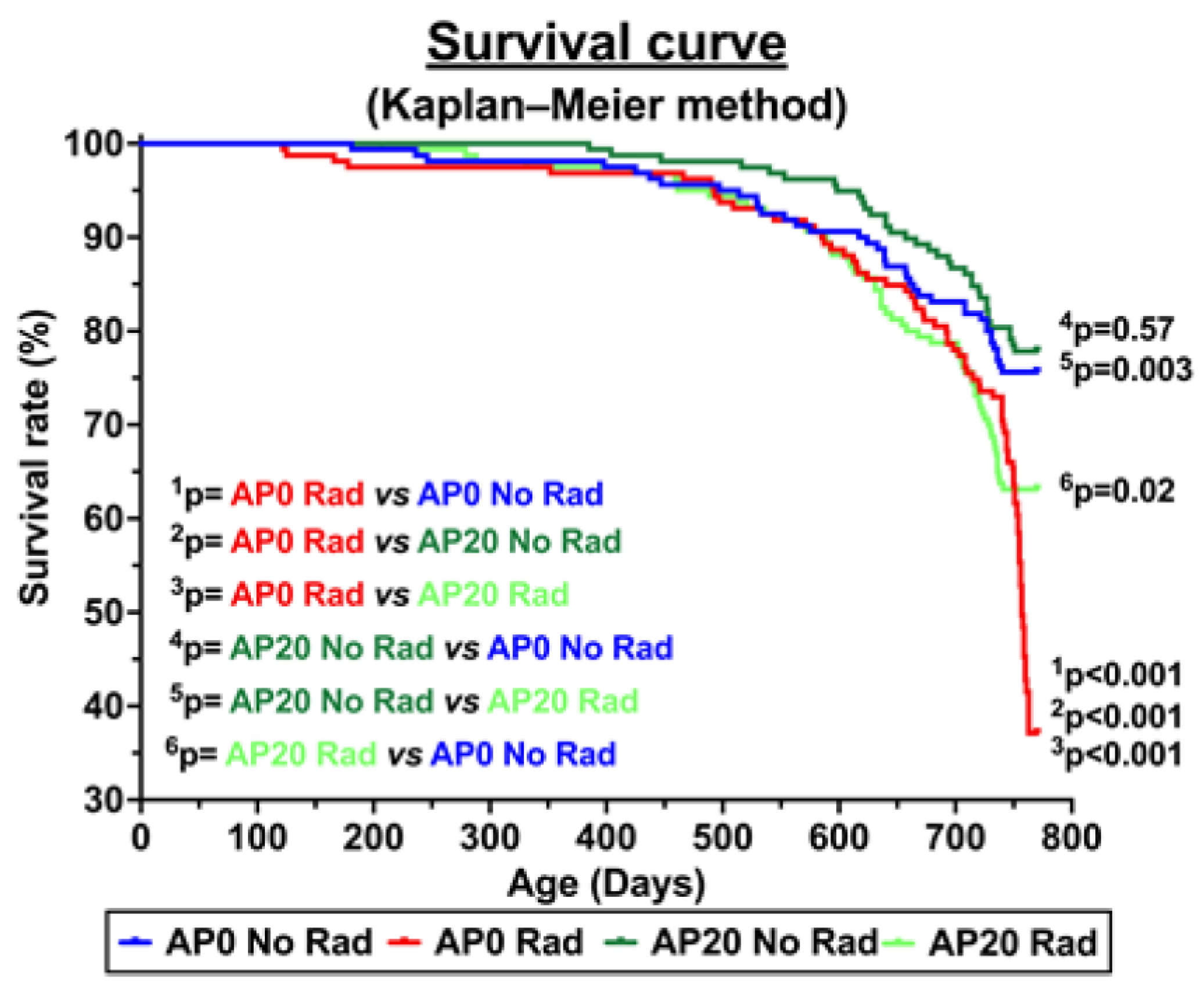

3.2. Survival Curve and Acute Lymphoma/Lymphoblastic Leukemia Incidence

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cucinotta, F.A. Space Radiation Risks for Astronauts on Multiple International Space Station Missions. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e96099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sishc, B.J.; Zawaski, J.; Saha, J.; Carnell, L.S.; Fabre, K.M.; Elgart, S.R. The Need for Biological Countermeasures to Mitigate the Risk of Space Radiation-Induced Carcinogenesis, Cardiovascular Disease, and Central Nervous System Deficiencies. Life Sci. Space Res. 2022, 35, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnell, L.S. Spaceflight medical countermeasures: A strategic approach for mitigating effects from solar particle events. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2020, 97, S125–S131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peanlikhit, T.; Honikel, L.; Liu, J.; Zimmerman, T.; Rithidech, K. Countermeasure efficacy of apigenin for silicon-ion-induced early damage in blood and bone marrow of exposed C57BL/6J mice. Life Sci. Space Res. 2022, 35, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rithidech, K.N.; Peanlikhit, T.; Honikel, L.; Li, J.; Liu, J.; Karakach, T.; Zimmerman, T.; Welsh, J. Consumption of Apigenin Prevents Radiation-induced Gut Dysbiosis in Male C57BL/6J Mice Exposed to Silicon Ions. Radiat. Res. 2024, 201, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.P.; Brown, S.L.; Georges, G.E.; Hauer-Jensen, M.; Hill, R.P.; Huser, A.K.; Kirsch, D.G.; MacVittie, T.J.; Mason, K.A.; Medhora, M.M.; et al. Animal Models for Medical Countermeasures to Radiation Exposure. Radiat. Res. 2010, 173, 557–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kominami, R.; Niwa, O. Radiation carcinogenesis in mouse thymic lymphomas. Cancer Sci. 2006, 97, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartge, P.; Smith, M.T. Environmental and behavioral factors and the risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2007, 16, 367–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, H.S.; Brown, M.B.; Paull, J. Influence of postirradiation thymectomy and of thymic implants on lymphoid tumor incidence in C57BL mice. Cancer Res. 1953, 13, 677–680. [Google Scholar]

- Rivina, L.; Schiestl, R. Mouse Models for Efficacy Testing of Agents against Radiation Carcinogenesis—A Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 10, 107–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, H.; Myers, D.D.; Fox, R.R.; Laird, C.W. Occurrence, pathological features, and propagation of gonadal teratomas in inbred mice and in rabbits. Cancer Res. 1970, 30, 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hoag, W.G. Spontaneous cancer in mice*. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1963, 108, 805–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, H.S. Observations on radiation-induced lymphoid tumors of mice. Cancer Res. 1947, 7, 141–147. [Google Scholar]

- Milder, C.M.; Chappell, L.; Charvat, J.M.; Van Baalen, M.; Huff, J.L.; Semone, E.J. Cancer Risk in Astronauts: A Constellation of Uncommon Consequences; NTRS-NAS Technical Reports Series; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sauvaget, C.; Kasagi, F.; Waldren, C.A. Dietary factors and cancer mortality among atomic-bomb survivors. Mutat. Res. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2004, 551, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, A.R. Biological effects of space radiation and development of effective countermeasures. Life Sci. Space Res. 2014, 1, 10–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, F.J.; Tang, M.-S.; Frenkel, K.; Nádas, A.; Wu, F.; Uddin, A.; Zhang, R. Induction and prevention of carcinogenesis in rat skin exposed to space radiation. Radiat. Environ. Biophys. 2007, 46, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, A.R.; Davis, J.G.; Carlton, W.; Ware, J.H. Effects of Dietary Antioxidant Supplementation on the Development of Malignant Lymphoma and Other Neoplastic Lesions in Mice Exposed to Proton or Iron-Ion Radiation. Radiat. Res. 2008, 169, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, A.R.; Ware, J.H.; Carlton, W.; Davis, J.G. Suppression of the Later Stages of Radiation-Induced Carcinogenesis by Antioxidant Dietary Formulations. Radiat. Res. 2011, 176, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peanlikhit, T.; Aryal, U.; Welsh, J.S.; Shroyer, K.R.; Rithidech, K.N. Evaluation of the Inhibitory Potential of Apigenin and Related Flavonoids on Various Proteins Associated with Human Diseases Using AutoDock. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B.; Venditti, A.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Kręgiel, D.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Durazzo, A.; Lucarini, M.; Santini, A.; Souto, E.B.; Novellino, E.; et al. The therapeutic potential of apigenin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, X.; Qi, M.; Li, P.; Zhan, Y.; Shao, H. Apigenin in cancer therapy: Anti-cancer effects and mechanisms of action. Cell Biosci. 2017, 7, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, Z.; Sadeer, N.B.; Hussain, M.; Mahwish; Alsagaby, S.A.; Imran, M.; Mumtaz, T.; Umar, M.; Tauseef, A.; Al Abdulmonem, W.; et al. Therapeutical properties of apigenin: A review on the experimental evidence and basic mechanisms. Int. J. Food Prop. 2023, 26, 1914–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, E.; Goel, A.; Gupta, K.; Gupta, S. Plant Flavone Apigenin: An Emerging Anticancer Agent. Curr. Pharmacol. Rep. 2017, 3, 423–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, S.; Gupta, S. Apigenin: A Promising Molecule for Cancer Prevention. Pharm. Res. 2010, 27, 962–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.U.; Dagur, H.S.; Khan, M.; Malik, N.; Alam, M. Mushtaque Therapeutic role of flavonoids and flavones in cancer prevention: Current trends and future perspectives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. Rep. 2021, 3, 100010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, A.H.; Alsahli, M.A.; Almatroudi, A.; Almogbel, M.A.; Khan, A.A.; Anwar, S.; Almatroodi, S.A. The Potential Role of Apigenin in Cancer Prevention and Treatment. Molecules 2022, 27, 6051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, J.J.A.; Alblas, J.; van der Pol, S.M.A.; van Tol, E.A.F.; Dijkstra, C.D.; de Vries, H.E. Flavonoids influence monocytic GTPase activity and are protective in experimental allergic encephalitis. J. Exp. Med. 2004, 200, 1667–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, S.; Shankar, E.; Fu, P.; MacLennan, G.T.; Gupta, S. Suppression of NF-κB and NF-κB-regulated gene expression by apigenin through IκBα and IKK pathway in TRAMP mice. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dross, R.; Xue, Y.; Knudson, A.; Pelling, J.C. The Chemopreventive Bioflavonoid Apigenin Modulates Signal Transduction Pathways in Keratinocyte and Colon Carcinoma Cell Lines. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 3800S–3804S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.; Gupta, S. Apigenin-induced Cell Cycle Arrest is Mediated by Modulation of MAPK, PI3K-Akt, and Loss of Cyclin D1 Associated Retinoblastoma Dephosphorylation in Human Prostate Cancer Cells. Cell Cycle 2007, 6, 1102–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, N.; Rajendra Prasad, N.; Kanimozhi, G.; Agilan, B. Apigenin prevents gamma radiation-induced gastrointestinal damages by modulating inflammatory and apoptotic signalling mediators. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 36, 1631–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, D.; Shukla, S.; Gupta, S. Apigenin and cancer chemoprevention: Progress, potential and promise (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 2007, 30, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefort, É.C.; Blay, J. Apigenin and its impact on gastrointestinal cancers. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2013, 57, 126–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossatelli, L.; Maroccia, Z.; Fiorentini, C.; Bonucci, M. Resources for Human Health from the Plant Kingdom: The Potential Role of the Flavonoid Apigenin in Cancer Counteraction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 25, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahbub, A.A.; Le Maitre, C.L.; Cross, N.A.; Jordan-Mahy, N. The effect of apigenin and chemotherapy combination treatments on apoptosis-related genes and proteins in acute leukaemia cell lines. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rithidech, K.N.; Tungjai, M.; Whorton, E.B. Protective effect of apigenin on radiation-induced chromosomal damage in human lymphocytes. Mutat. Res. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2005, 585, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rithidech, K.N.; Tungjai, M.; Reungpatthanaphong, P.; Honikel, L.; Simon, S.R. Attenuation of oxidative damage and inflammatory responses by apigenin given to mice after irradiation. Mutat. Res. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2012, 749, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, N.; Prasad, N.R. Apigenin, a dietary antioxidant, modulates gamma radiation-induced oxidative damages in human peripheral blood lymphocytes. Biomed. Prev. Nutr. 2012, 2, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, N.; Prasad, N.R.; Kanimozhi, G.; Hasan, A.Q. Apigenin ameliorates gamma radiation-induced cytogenetic alterations in cultured human blood lymphocytes. Mutat. Res. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2012, 747, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddique, Y.H.; Afzal, M. Protective effect of apigenin against hydrogen peroxide induced genotoxic damage on cultured human peripheral blood lymphocytes. J. Appl. Biomed. 2009, 7, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, Y.H.; Afzal, M. Antigenotoxic effect of apigenin against mitomycin C induced genotoxic damage in mice bone marrow cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2009, 47, 536–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, N.; Prasad, R.; Thayalan, K. Apigenin protects gamma-radiation induced oxidative stress, hematological changes and animal survival in whole body irradiated Swiss albino mice. Int. J. Nutr. Pharmacol. Neurol. Dis. 2012, 2, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, G.; Stevens, K.A.; Russell, R.J. Nutritions; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Harkness, J.E.; Wagner, J.E. The Biology and Medicine of Rabbits and Rodents, 2nd ed.; Lea & Febiger: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Rithidech, K.N.; Reungpatthanaphong, P.; Tungjai, M.; Jangiam, W.; Honikel, L.; Whorton, E.B. Persistent depletion of plasma gelsolin (pGSN) after exposure of mice to heavy silicon ions. Life Sci. Space Res. 2018, 17, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tungjai, M.; Whorton, E.B.; Rithidech, K.N. Persistence of apoptosis and inflammatory responses in the heart and bone marrow of mice following whole-body exposure to 28Silicon (28Si) ions. Radiat. Environ. Biophys. 2013, 52, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morse, H.C., III; Anver, M.R.; Fredrickson, T.N.; Haines, D.C.; Harris, A.W.; Harris, N.L.; Jaffe, E.S.; Kogan, S.C.; MacLennan, I.C.M.; Pattengale, P.K.; et al. Bethesda proposals for classification of lymphoid neoplasms in mice. Blood 2002, 100, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleiss, J.L. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportion, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jangiam, W.; Tungjai, M.; Rithidech, K.N. Induction of chronic oxidative stress, chronic inflammation and aberrant patterns of DNA methylation in the liver of titanium-exposed CBA/CaJ mice. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2015, 91, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rithidech, K.N.; Jangiam, W.; Tungjai, M.; Gordon, C.; Honikel, L.; Whorton, E.B. Induction of Chronic Inflammation and Altered Levels of DNA Hydroxymethylation in Somatic and Germinal Tissues of CBA/CaJ Mice Exposed to 48Ti Ions. Front. Oncol. 2016, 6, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rithidech, P.K.R.; Honikel, L.; Whorton, E.B. Genomic Instability and Chronic Inflammation in Bone Marrow Cells of Mice Exposed Whole Body to Low Dose Rates of Protons. NASA. 2011. Available online: www.dsls.usra.edu/meetings/hrp2011/ (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Gridley, D.S.; Nelson, G.A.; Peters, L.L.; Kostenuik, P.J.; Bateman, T.A.; Morony, S.; Stodieck, L.S.; Lacey, D.L.; Simske, S.J.; Pecaut, M.J. Genetic models in applied physiology: Selected contribution: Effects of spaceflight on immunity in the C57BL/6 mouse. II. Activation, cytokines, erythrocytes, and platelets. J. Appl. Physiol. 2003, 94, 2095–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datta, K.; Suman, S.; Kallakury, B.V.S.; Fornace, A.J. Exposure to Heavy Ion Radiation Induces Persistent Oxidative Stress in Mouse Intestine. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.W.; Nishiyama, N.C.; Pecaut, M.J.; Campbell-Beachler, M.; Gifford, P.; Haynes, K.E.; Becronis, C.; Gridley, D.S. Simulated Microgravity and Low-Dose/Low-Dose-Rate Radiation Induces Oxidative Damage in the Mouse Brain. Radiat. Res. 2016, 185, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baulch, J.E.; Craver, B.M.; Tran, K.K.; Yu, L.; Chmielewski, N.; Allen, B.D.; Limoli, C.L. Persistent oxidative stress in human neural stem cells exposed to low fluences of charged particles. Redox Biol. 2015, 5, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, B.P.; Giedzinski, E.; Izadi, A.; Suarez, T.; Lan, M.L.; Tran, K.K.; Acharya, M.M.; Nelson, G.A.; Raber, J.; Parihar, V.K.; et al. Functional Consequences of Radiation-Induced Oxidative Stress in Cultured Neural Stem Cells and the Brain Exposed to Charged Particle Irradiation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014, 20, 1410–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suman, S.; Rodriguez, O.C.; Winters, T.A.; Fornace, A.J., Jr.; Albanese, C.; Datta, K. Therapeutic and space radiation exposure of mouse brain causes impaired DNA repair response and premature senescence by chronic oxidant production. Aging 2013, 5, 607–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridharan, D.M.; Asaithamby, A.; Bailey, S.M.; Costes, S.V.; Doetsch, P.W.; Dynan, W.S.; Kronenberg, A.; Rithidech, K.N.; Saha, J.; Snijders, A.M.; et al. Understanding Cancer Development Processes after HZE-Particle Exposure: Roles of ROS, DNA Damage Repair and Inflammation. Radiat. Res. 2015, 183, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rithidech, K.N.; Udomtanakunchai, C.; Honikel, L.M.; Whorton, E.B. No Evidence for the in vivo Induction of Genomic Instability by Low Doses of 137Cs Gamma Rays in Bone Marrow Cells of BALB/cJ and C57BL/6J Mice. Dose-Response 2011, 10, 11–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chelakkot, C.; Ghim, J.; Ryu, S.H. Mechanisms regulating intestinal barrier integrity and its pathological implications. Exp. Mol. Med. 2018, 50, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.-J.; Li, S.; Gan, R.-Y.; Zhou, T.; Xu, D.-P.; Li, H.-B. Impacts of Gut Bacteria on Human Health and Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 7493–7519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, Y.; Wang, X.; Guo, Y.; Yan, J.; Abuduwaili, A.; Aximujiang, K.; Yan, J.; Wu, M. Gut microbiota influence tumor development and Alter interactions with the human immune system. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 40, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, T.; Sharma, P.; Are, A.C.; Vickers, S.M.; Dudeja, V. New Insights Into the Cancer–Microbiome–Immune Axis: Decrypting a Decade of Discoveries. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 622064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durack, J.; Lynch, S.V. The gut microbiome: Relationships with disease and opportunities for therapy. J. Exp. Med. 2019, 216, 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanabani, S.S. Impact of Gut Microbiota on Lymphoma: New Frontiers in Cancer Research. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2024, 25, e82–e89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goswami, M.; Bose, P.D. Gut microbial dysbiosis in the pathogenesis of leukemia: An immune-based perspective. Exp. Hematol. 2024, 133, 104211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Shoubaky, G.A.; Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Mansour, M.H.; Salem, E.A. Isolation and Identification of a Flavone Apigenin from Marine Red Alga Acanthophora spicifera with Antinociceptive and Anti-Inflammatory Activities. J. Exp. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Case # | Days, Post Irradiation (Latency) | Complete Blood Count with Differential Count | Histopathological Evaluation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone | Gut | Kidney | Liver | Lung | Pancreas | Spleen | Thymus | |||

| 1 | 445 | CBC RBC = 2.94 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 840 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 23.75 × 103 cells/µL Differential count nd | na | na | na | LL | npd | na | LL | LL |

| 2 | 449 | CBC RBC = 4.74 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 540 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 43.35 × 103 cells/µL Differential count nd | no | na | na | npd | LL | na | npd | LL |

| 3 | 555 | CBC nd | no | na | npd | npd | npd | na | npd | LL |

| 4 | 638 | CBC RBC = 6.51 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 167 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 2.82 × 103 cells/µL Differential count NEUT = 1.21 × 103 cells/µL LYMPH = 1.03 × 103 cells/µL MONO = 0.19 × 103 cells/µL EOS = 0.31 × 103 cells/µL BASO = 0.07 × 103 cells/µL | no | npd | npd | LL | LL | npd | LL | na |

| 5 | 643 | CBC RBC = 8.01 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 1251 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 5.42 × 103 cells/µL Differential count NEUT = 1.39 × 103 cells/µL LYMPH = 1.91 × 103 cells/µL MONO = 0.57 × 103 cells/µL EOS = 0.86 × 103 cells/µL BASO = 0.68 × 103 cells/µL | no | na | npd | npd | npd | na | LL | na |

| 6 | 652 | CBC RBC = 6.35 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 1067 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 5.14 × 103 cells/µL Differential count NEUT = 1.62 × 103 cells/µL LYMPH = 1.9 × 103 cells/µL MONO = 0.43 × 103 cells/µL EOS = 0.82 × 103 cells/µL BASO = 0.37 × 103 cells/µL | no | na | npd | npd | npd | na | LL | LL |

| 7 | 656 | CBC RBC = 6.54 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 1229 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 4.92 × 103 cells/µL Differential count NEUT = 1.64 × 103 cells/µL LYMPH = 1.58 × 103 cells/µL MONO = 0.2 × 103 cells/µL EOS = 0.36 × 103 cells/µL BASO = 1.14 × 103 cells/µL | na | npd | npd | npd | LL | npd | npd | LL |

| Case # | Days, Post Irradiation (Latency) | Complete Blood Count with Differential Count | Histopathological Evaluation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone | Gut | Kidney | Liver | Lung | Pancreas | Spleen | Thymus | |||

| 1 | 382 | CBC RBC = 15.65 × 106 cells/µL PLT = uncountable WBC = uncountable Differential count nd | no | npd necrosis | npd | LL | npd | na | LL | na |

| 2 | 406 | CBC RBC = 5.98 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 180 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 15.4 × 103 cells/µL Differential count nd | no | npd | na | LL | LL | npd | LL | na |

| 3 | 413 | CBC RBC = 8.3 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 480 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 3.35 × 103 cells/µL Differential count nd | na | na | npd | npd | npd | na | npd | LL |

| 4 | 425 | CBC RBC = 3.66 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 120 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 31.45 × 103 cells/µL Differential count nd | no | na | npd | LL | npd | na | LL | na |

| 5 | 449 | CBC RBC = 2.28 × 106 cells/µL PLT =270 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 295.5 × 103 cells/µL Differential count nd | no | npd | npd | npd | npd | na | LL | na |

| 6 | 460 | CBC RBC = 3.26 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 320 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 226.75 × 103 cells/µL Differential count nd | no | npd | npd | LL | LL | na | LL | na |

| 7 | 501 | CBC RBC = 2.76 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 20 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 518 × 103 cells/µL Differential count nd | no | na | npd | LL | npd | na | LL | na |

| 8 | 509 | CBC RBC = 1.28 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 40 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 292 × 103 cells/µL Differential count nd | no | npd | npd | fatty liver | npd | npd | LL | na |

| 9 | 581 | CBC RBC = 5.52 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 875 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 4.92 × 103 cells/µL Differential count nd | no | na | npd | npd | npd | na | npd | LL |

| 10 | 608 | CBC RBC = 3.35 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 100 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 6.28 × 103 cells/µL Differential count NEUT = 3.21 × 103 cells/µL LYMPH = 2.12 × 103 cells/µL MONO = 0.7 × 103 cells/µL EOS = 0.16 × 103 cells/µL BASO = 0.09 × 103 cells/µL | no | npd necrosis | npd | LL | npd | npd | lpd | na |

| 11 | 609 | CBC RBC = 7.01 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 1741 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 3.88 × 103 cells/µL Differential count NEUT = 1.64 × 103 cells/µL LYMPH = 1.58 × 103 cells/µL MONO = 0.2 × 103 cells/µL EOS = 0.36 × 103 cells/µL BASO = 1.14 × 103 cells/µL | na | na | npd | npd | npd | na | npd | LL |

| 12 | 636 | CBC RBC = 7.7 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 1741 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 3.88 × 103 cells/µL Differential count NEUT = 1 × 103 cells/µL LYMPH = 1.37 × 103 cells/µL MONO = 0.35 × 103 cells/µL EOS = 0.66 × 103 cells/µL BASO = 0.5 × 103 cells/µL | no | na | npd | LL | npd | na | LL | LL |

| 13 | 637 | CBC RBC = 2.94 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 503 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 8.94 × 103 cells/µL Differential count NEUT = 4.34 × 103 cells/µL LYMPH = 3.04 × 103 cells/µL MONO = 0.67 × 103 cells/µL EOS = 0.72 × 103 cells/µL BASO = 0.16 × 103 cells/µL | no | npd | npd | LL | npd | npd | npd | na |

| 14 | 648 | CBC RBC = 3.52 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 376 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 1.54 × 103 cells/µL Differential count NEUT = 0.52 × 103 cells/µL LYMPH = 0.56 × 103 cells/µL MONO = 0.17 × 103 cells/µL EOS = 0.26 × 103 cells/µL BASO = 0.03 × 103 cells/µL | no | npd | npd | LL | LL | npd | LL | na |

| 15 | 660 | CBC RBC = 3.95 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 1178 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 4.12 × 103 cells/µL Differential count NEUT = 1.07 × 103 cells/µL LYMPH = 0.88 × 103 cells/µL MONO = 0.35 × 103 cells/µL EOS = 0.96 × 103 cells/µL BASO = 0.86 × 103 cells/µL | no | npd | npd | npd | npd | npd | LL | LL |

| 16 | 675 | CBC RBC = 8.47 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 1872 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 11.28 × 103 cells/µL Differential count NEUT = 3.25 × 103 cells/µL LYMPH = 5.6 × 103 cells/µL MONO = 0.95 × 103 cells/µL EOS = 0.95 × 103 cells/µL BASO = 0.53 × 103 cells/µL | no | npd | npd | liver tumor | npd | na | LL | na |

| 17 | 675 | CBC RBC = 8.41 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 1872 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 10.82 × 103 cells/µL Differential count NEUT = 3.21 × 103 cells/µL LYMPH = 4.71 × 103 cells/µL MONO = 1.13 × 103 cells/µL EOS = 1.33 × 103 cells/µL BASO = 0.43 × 103 cells/µL | no | na | npd | fatty liver | npd | na | LL | LL |

| 18 | 676 | CBC RBC = 7.42 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 1825 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 12.04 × 103 cells/µL Differential count NEUT = 2.64 × 103 cells/µL LYMPH = 6.05 × 103 cells/µL MONO = 1.12 × 103 cells/µL EOS = 1.67 × 103 cells/µL BASO = 0.56 × 103 cells/µL | no | npd | npd | npd | LL | npd | LL | na |

| Case # | Days, Post Irradiation (Latency) | Complete Blood Count with Differential Count | Histopathological Evaluation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone | Gut | Kidney | Liver | Lung | Pancreas | Spleen | Thymus | |||

| 1 | 538 | CBC RBC = 2.22 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 460 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 161.2 × 103 cells/µL Differential count nd | na | npd | npd | LL | npd | npd | lpd | na |

| 2 | 560 | CBC RBC = 3.6 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 350 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 480 × 103 cells/µL Differential count nd | na | npd | npd | LL | LL | npd | lpd | na |

| 3 | 643 | CBC RBC = 6.15 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 1178 × 103 cells/µL WBC = high Differential count NEUT = high LYMPH = high MONO = 69.44 × 103 cells/µL EOS = 68.24 × 103 cells/µL BASO = 21.78 × 103 cells/µL | no | na | npd | LL | LL | na | LL | LL |

| 4 | 643 | CBC RBC = 4.77 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 180 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 11.76 × 103 cells/µL Differential count NEUT = 7.2 × 103 cells/µL LYMPH = 2.96 × 103 cells/µL MONO = 0.84 × 103 cells/µL EOS = 0.8 × 103 cells/µL BASO = 0.11 × 103 cells/µL | no | npd | npd | LL | LL | npd | LL | na |

| 5 | 644 | CBC RBC = 6.25 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 2365 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 6.36 × 103 cells/µL Differential count NEUT = 1.79 × 103 cells/µL LYMPH = 2.77 × 103 cells/µL MONO = 0.47 × 103 cells/µL EOS = 0.7 × 103 cells/µL BASO = 0.43 × 103 cells/µL | no | na | npd | npd | npd | na | LL | LL |

| 6 | 646 | CBC RBC = 9.09 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 1069 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 5.38 × 103 cells/µL Differential count NEUT = 1.53 × 103 cells/µL LYMPH = 2.54 × 103 cells/µL MONO = 0.47 × 103 cells/µL EOS = 0.58 × 103 cells/µL BASO = 0.26 × 103 cells/µL | no | na | npd | LL | npd | na | LL | na |

| 7 | 663 | CBC RBC = 5.8 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 879 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 3.43 × 103 cells/µL Differential count NEUT = 1.57 × 103 cells/µL LYMPH = 1.06 × 103 cells/µL MONO = 0.25 × 103 cells/µL EOS = 0.96 × 103 cells/µL BASO = 0.5 × 103 cells/µL | no | npd | nod | npd | npd | na | LL | LL |

| Case # | Days, Post Irradiation (Latency) | Complete Blood Count with Differential Count | Histopathological Evaluation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone | Gut | Kidney | Liver | Lung | Pancreas | Spleen | Thymus | |||

| 1 | 479 | CBC RBC = 3.84 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 300 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 182 × 103 cells/µL Differential count nd | no | npd | LL | necrosis | na | npd | LL | LL |

| 2 | 537 | CBC RBC = 4.075 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 1475 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 245 × 103 cells/µL Differential count nd | no | na | npd | npd | npd | npd | npd | LL |

| 3 | 624 | CBC nd Differential count nd | no | npd | npd | LL | LL | na | LL | na |

| 4 | 633 | CBC RBC = 6.86 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 1965 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 3.24 × 103 cells/µL Differential count NEUT = 0.89 × 103 cells/µL LYMPH = 1.26 × 103 cells/µL MONO = 0.21 × 103 cells/µL EOS = 0.8 × 103 cells/µL BASO = 0.11 × 103 cells/µL | no | na | npd | na | npd | na | LL | LL |

| 5 | 637 | CBC RBC = 6.25 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 2365 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 6.36 × 103 cells/µL Differential count NEUT = 0.96 × 103 cells/µL LYMPH = 1.48 × 103 cells/µL MONO = 0.34 × 103 cells/µL EOS = 0.91 × 103 cells/µL BASO = 0.66 × 103 cells/µL | no | na | npd | necrosis | npd | na | npd | LL |

| 6 | 639 | CBC RBC = 5.03 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 1195 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 8.96 × 103 cells/µL Differential count NEUT = 3.31 × 103 cells/µL LYMPH = 3.61 × 103 cells/µL MONO = 0.7 × 103 cells/µL EOS = 0.97 × 103 cells/µL BASO = 0.36 × 103 cells/µL | no | na | npd | LL | npd | na | LL | LL |

| 7 | 646 | CBC RBC = 5.25 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 1007 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 11.08 × 103 cells/µL Differential count NEUT = 3.75 × 103 cells/µL LYMPH = 4.48 × 103 cells/µL MONO = 0.38 × 103 cells/µL EOS = 1.24 × 103 cells/µL BASO = 1.23 × 103 cells/µL | no | npd | npd | npd | npd | npd | npd | LL |

| 8 | 650 | CBC RBC = 8.14 × 106 cells/µL PLT = 996 × 103 cells/µL WBC = 10.08 × 103 cells/µL Differential count NEUT = 4.11 × 103 cells/µL LYMPH = 1.92 × 103 cells/µL MONO = 0.51 × 103 cells/µL EOS = 3.06 × 103 cells/µL BASO = 0.48 × 103 cells/µL | no | na | npd | necrosis | na | na | LL | LL |

| Treatment Group | RBC (×106 Cells/µL) | PLT (×103 Cells/µL) | WBC (×103 Cells/µL) | LYMPH (×103 Cells/µL) | NEUT (×103 Cells/µL) | MONO (×103 Cells/µL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AP 0 No Rad | 5.85 ± 0.72 | 849 ± 174.57 | 14.23 ± 6.62 | 1.61 ± 0.21 | 1.47 ± 0.10 | 0.35 ± 0.09 |

| AP 0 Rad | 5.64 ± 0.81 | 77.94 ± 182.15 | 85.30 ± 36.90 | 2.88 ± 0.69 | 2.32 ± 0.44 | 0.63 ±0.13 |

| AP 20 No Rad | 5.41 ± 0.83 | 925 ± 278.70 | 111.36 ± 77.93 | 2.33 ± 0.43 | 3.02 ± 0.43 | 14.29 ±13.79 |

| AP 20 Rad | 5.64 ± 0.58 | 1329 ± 257.76 | 38.54 ± 38.54 | 2.49 ± 0.61 | 2.66 ± 0.71 | 0.43 ± 0.08 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peanlikhit, T.; Liu, J.; Ahmed, T.; Welsh, J.S.; Karakach, T.; Shroyer, K.R.; Whorton, E., Jr.; Rithidech, K.N. Daily Consumption of Apigenin Prevents Acute Lymphoma/Lymphoblastic Leukemia in Male C57BL/6J Mice Exposed to Space-like Radiation. Cancers 2025, 17, 3513. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17213513

Peanlikhit T, Liu J, Ahmed T, Welsh JS, Karakach T, Shroyer KR, Whorton E Jr., Rithidech KN. Daily Consumption of Apigenin Prevents Acute Lymphoma/Lymphoblastic Leukemia in Male C57BL/6J Mice Exposed to Space-like Radiation. Cancers. 2025; 17(21):3513. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17213513

Chicago/Turabian StylePeanlikhit, Tanat, Jingxuan Liu, Tahmeena Ahmed, James S. Welsh, Tobias Karakach, Kenneth R. Shroyer, Elbert Whorton, Jr., and Kanokporn Noy Rithidech. 2025. "Daily Consumption of Apigenin Prevents Acute Lymphoma/Lymphoblastic Leukemia in Male C57BL/6J Mice Exposed to Space-like Radiation" Cancers 17, no. 21: 3513. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17213513

APA StylePeanlikhit, T., Liu, J., Ahmed, T., Welsh, J. S., Karakach, T., Shroyer, K. R., Whorton, E., Jr., & Rithidech, K. N. (2025). Daily Consumption of Apigenin Prevents Acute Lymphoma/Lymphoblastic Leukemia in Male C57BL/6J Mice Exposed to Space-like Radiation. Cancers, 17(21), 3513. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17213513