Integrating Functional Genomic Screens and Multi-Omics Data to Construct a Prognostic Model for Lung Adenocarcinoma and Validating SPC25

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

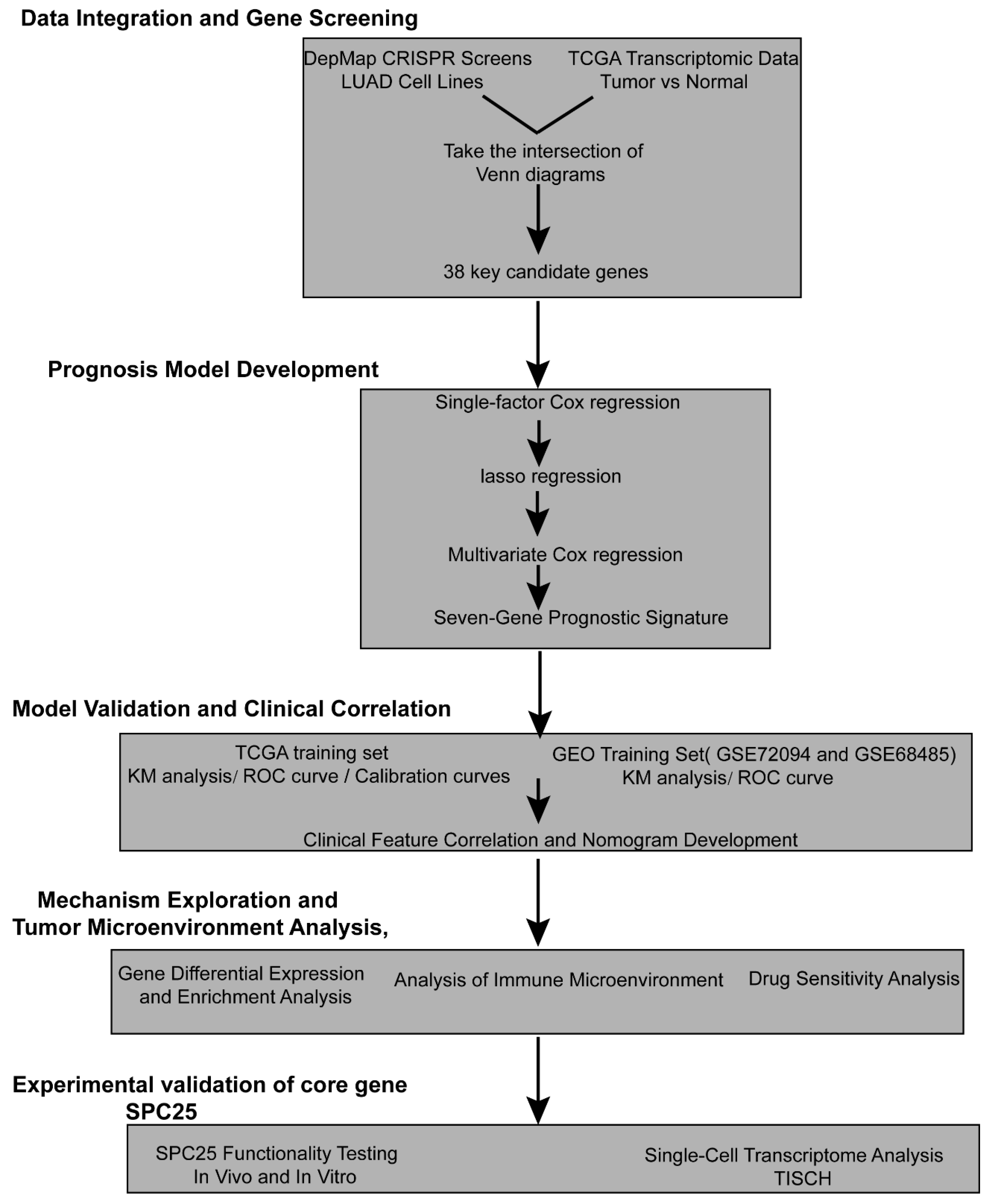

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.1.1. Identification of Crucial LUAD Genes

2.1.2. Construction of a Prognostic Model

2.1.3. Verification and Assessment of a Predictive Model

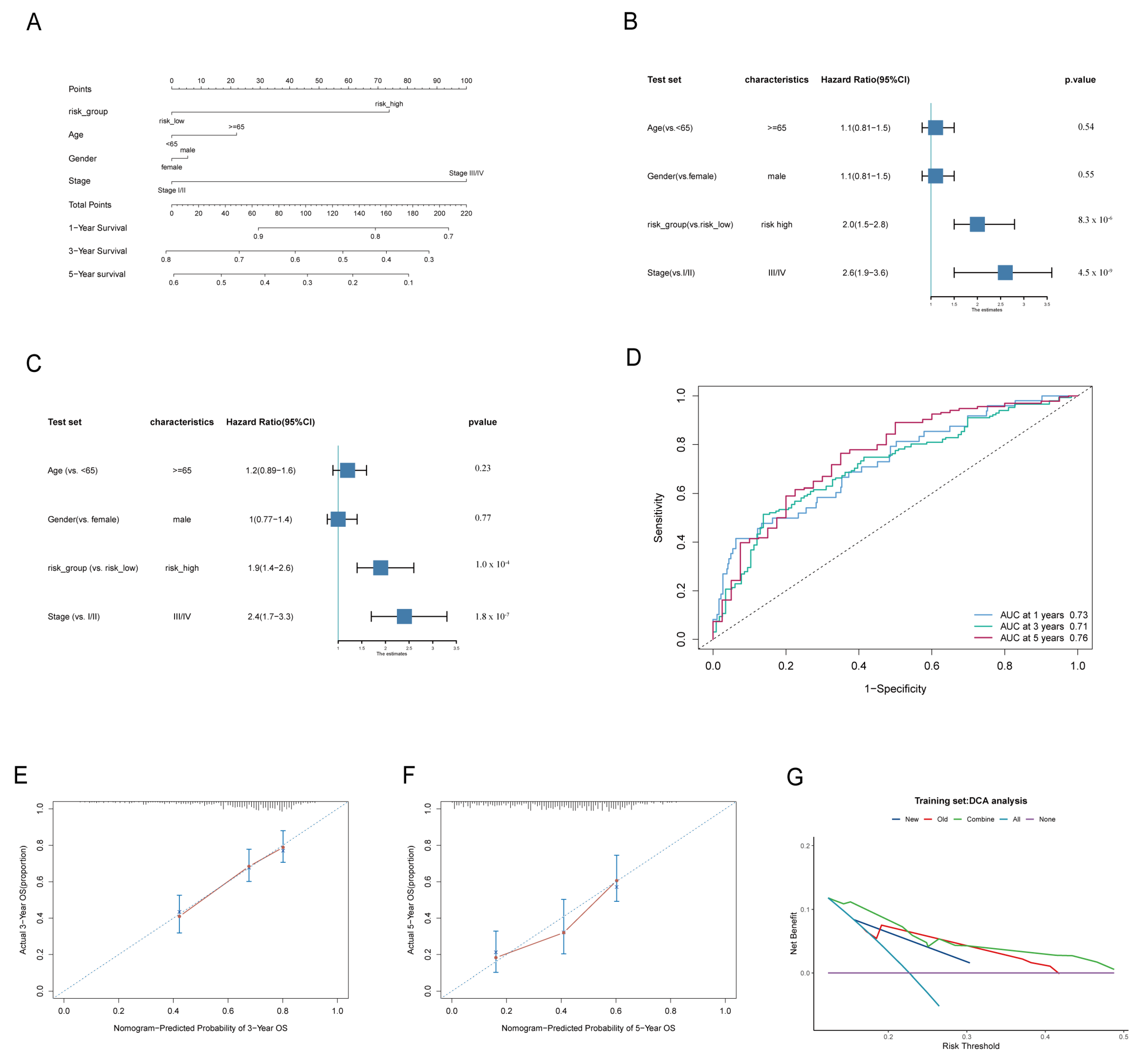

2.2. Establishment and Validation of a Nomogram Scoring System

2.3. Clinical Analyses Related to Risk Scores

2.4. Functional Enrichment Analysis Associated with Risk Score

2.5. Evaluation of Immune Cell Infiltration

2.6. Chemotherapy Response Prediction

2.7. Validation of Characteristic Genes

2.8. Role of Key Genes in Immunotherapy Efficacy and Prognosis for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

2.9. Cell Culture and Lentiviral Transfection

2.10. Western Blotting (WB)

2.11. Colony Formation Assays

2.12. Wound Closure Assays

2.13. Ethynyl Deoxyuridine (EDU) Proliferation Assay

2.14. Animal Experiments

2.15. Single Cell Sequencing Analysis

2.16. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

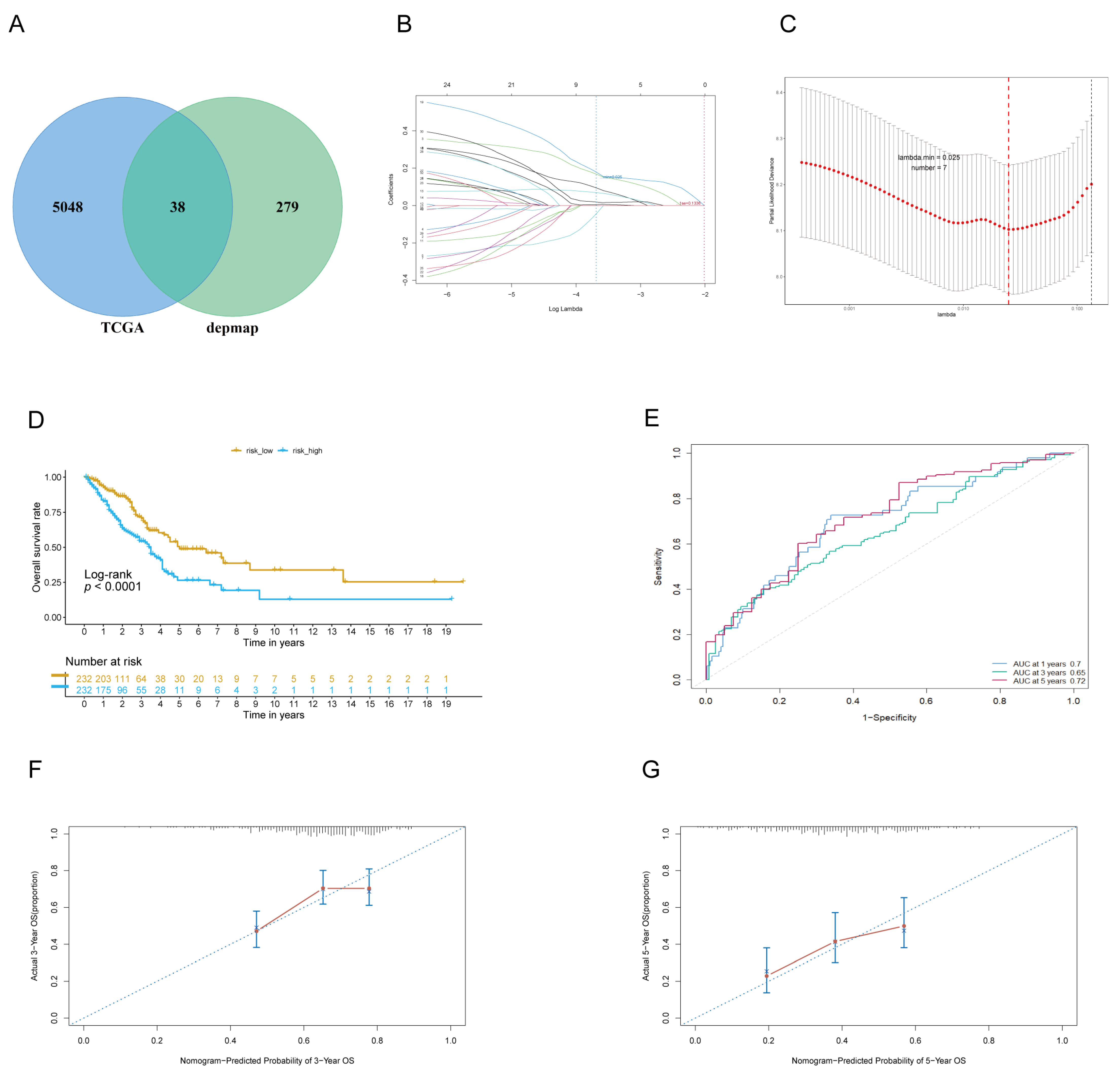

3.1. Identifying Lung Adenocarcinoma Dependence Genes (LADGs) and Developing Prognostic Signature

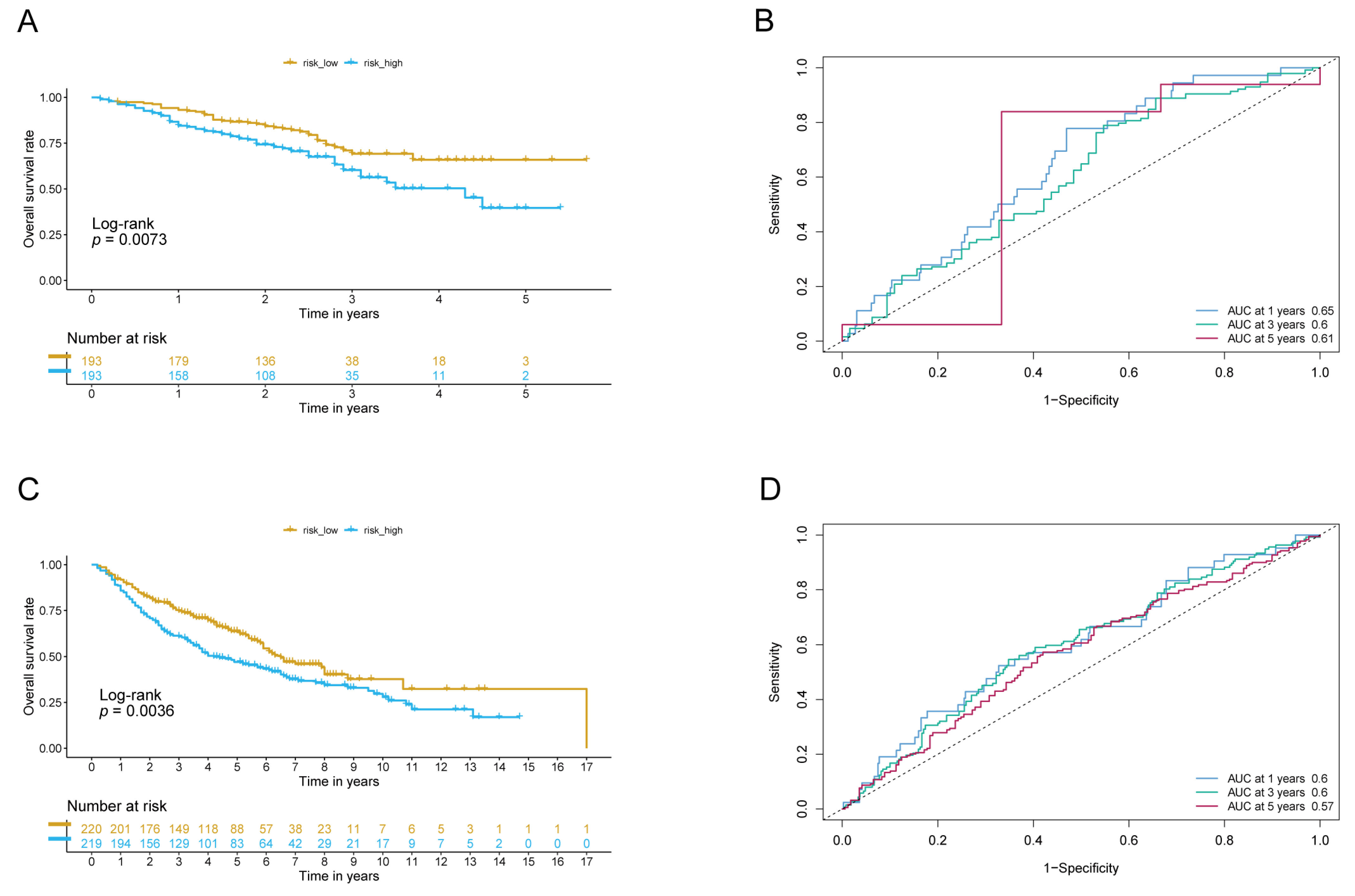

3.2. The Signature of LADGs Was Identified as a Significant Independent Prognostic Factor for LUAD

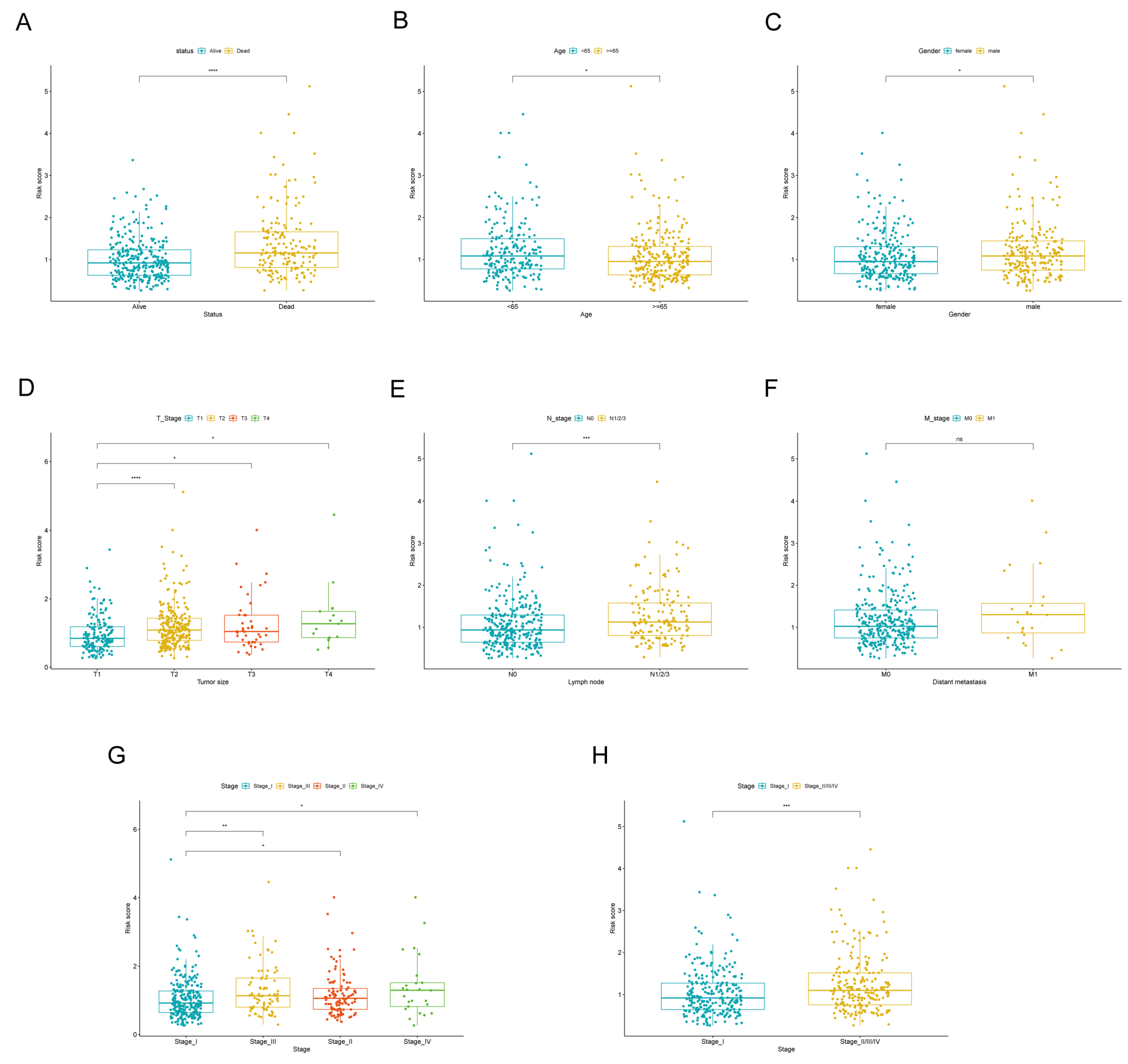

3.3. The Correlation Between Signature of LADGs and Clinical Characteristics

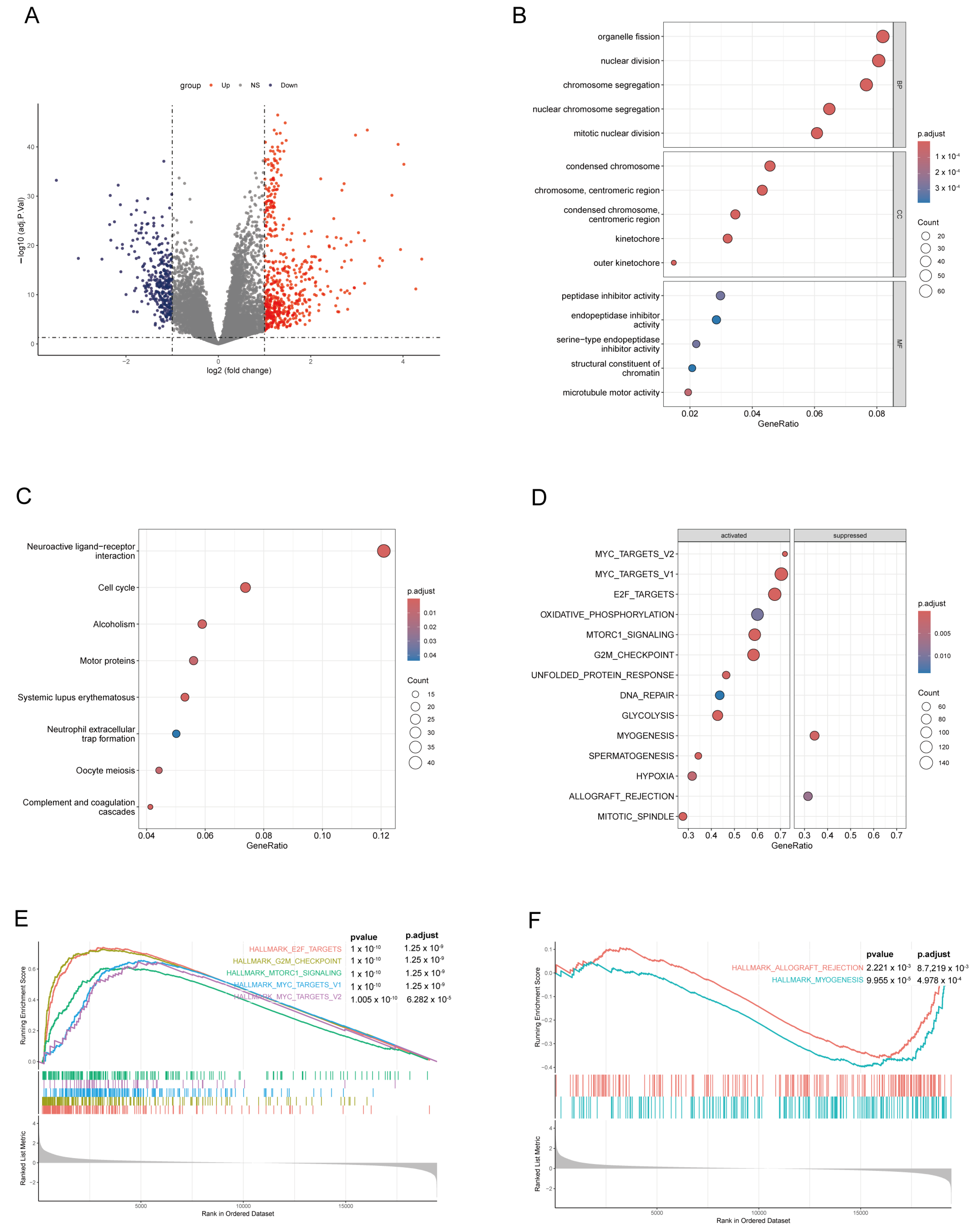

3.4. Differential Gene Analysis and Enrichment Analysis in High-Score and Low-Score Risk Groups on the LADGs Signature

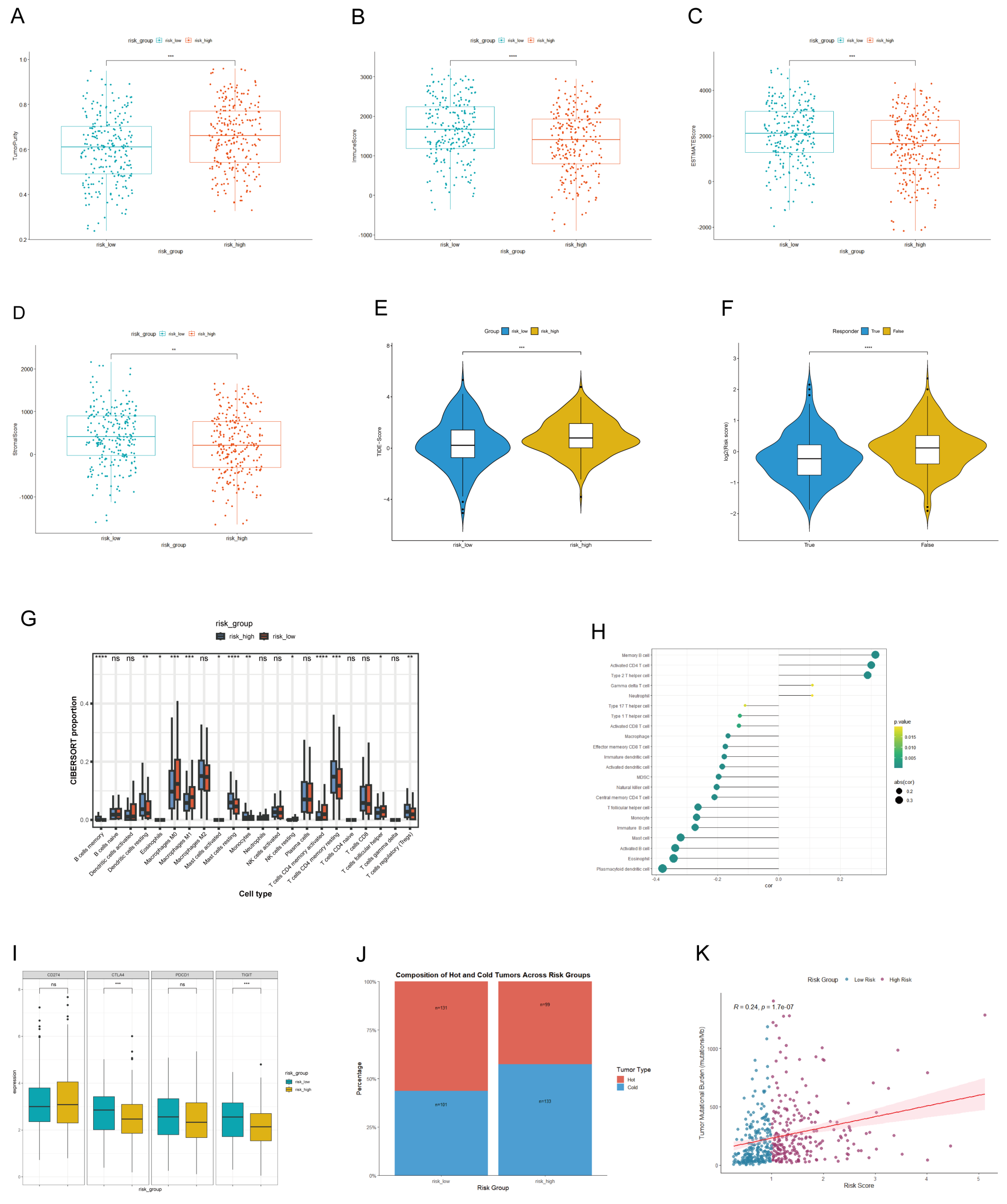

3.5. The Link Between LADGs Signature and Tumor Microenvironment

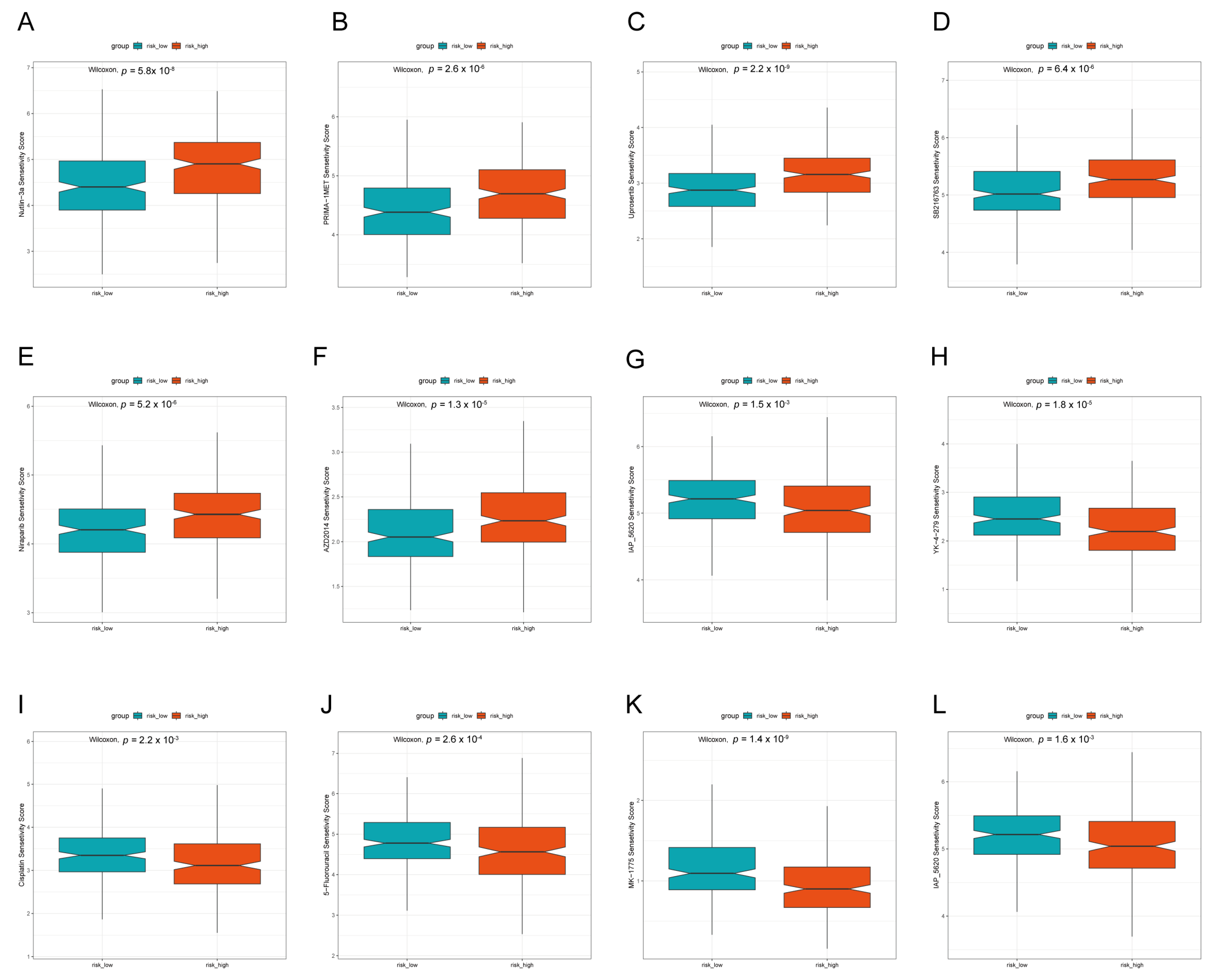

3.6. Prediction of Drug Treatment Response Based on LADGs Features

3.7. Expression and Localization of Signature Genes

3.8. Characteristic Genes Hold Promise as Biomarkers and Potential Targets for Immunotherapy

3.9. Verification of LADGs Expression and Function in LUAD Cells

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LUAD | Lung adenocarcinoma |

| LADGs | LUAD-dependent genes |

| LASSO | Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator |

| HPA | Human Protein Atlas |

| TCGA | The Cancer Genome Atlas |

| GEO | Gene Expression Omnibus |

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Yan, Q.; Fan, C.; Mo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Liao, Q.; Guo, C.; Li, G.; Zeng, Z.; et al. Overview and countermeasures of cancer burden in China. Sci. China Life Sci. 2023, 66, 2515–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai, A.A.; Solomon, B.J.; Sequist, L.V.; Gainor, J.F.; Heist, R.S. Lung cancer. Lancet 2021, 398, 535–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Lu, S.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, B.; Hu, C.; Lin, L.; Zhong, W.; et al. Expert consensus on treatment for stage III non-small cell lung cancer. iLABMED 2023, 1, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Lung Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2021, 325, 962–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Jiao, D.; Liu, A.; Wu, K. Tumor organoids: Applications in cancer modeling and potentials in precision medicine. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, A.; Li, J.; Li, M.; Liu, Y. Patient-derived xenograft model in cancer: Establishment and applications. Medcomm 2025, 6, e70059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokhanbigli, S.; Haghi, M.; Dua, K.; Oliver, B.G.G. Cancer-associated fibroblast cell surface markers as potential biomarkers or therapeutic targets in lung cancer. Cancer Drug Resist. 2024, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Shen, H.; Gu, W.; Zheng, H.; Wang, Y.; Ma, G.; Du, J. Prediction of prognosis, immunogenicity and efficacy of immunotherapy based on glutamine metabolism in lung adenocarcinoma. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 960738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, F.; Lu, S.; Guo, S.; Shi, R.; Zhai, Y.; Gao, Y.; Tao, X.; Jin, Z.; et al. Identification of a disulfidptosis-related genes signature for prognostic implication in lung adenocarcinoma. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 165, 107402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, M.; Zeng, Q.; Fan, T.; Lei, Y.; Wang, F.; Zheng, S.; Wang, X.; Zeng, H.; Tan, F.; Sun, N.; et al. Clinical Significance and Immunometabolism Landscapes of a Novel Recurrence-Associated Lipid Metabolism Signature In Early-Stage Lung Adenocarcinoma: A Comprehensive Analysis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 783495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Zhou, B.; Zhu, X.; Yang, F.; Jin, K.; Dai, J.; Zhu, Y.; Song, X.; Jiang, G. Differentiation-related genes in tumor-associated macrophages as potential prognostic biomarkers in non-small cell lung cancer. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1123840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Tokheim, C.; Gu, S.S.; Wang, B.; Tang, Q.; Li, Y.; Traugh, N.; Zeng, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; et al. In vivo CRISPR screens identify the E3 ligase Cop1 as a modulator of macrophage infiltration and cancer immunotherapy target. Cell 2021, 184, 5357–5374.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsherniak, A.; Vazquez, F.; Montgomery, P.G.; Weir, B.A.; Kryukov, G.; Cowley, G.S.; Gill, S.; Harrington, W.F.; Pantel, S.; Krill-Burger, J.M.; et al. Defining a Cancer Dependency Map. Cell 2017, 170, 564–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, R.M.; Bryan, J.G.; McFarland, J.M.; Weir, B.A.; Sizemore, A.E.; Xu, H.; Dharia, N.V.; Montgomery, P.G.; Cowley, G.S.; Pantel, S.; et al. Computational correction of copy number effect improves specificity of CRISPR–Cas9 essentiality screens in cancer cells. Nat. Genet. 2017, 49, 1779–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Director’s Challenge Consortium for the Molecular Classification of Lung Adenocarcinoma Gene expression–based survival prediction in lung adenocarcinoma: A multi-site, blinded validation study. Nat. Med. 2008, 14, 822–827. [CrossRef]

- Schabath, M.B.; A Welsh, E.; Fulp, W.J.; Chen, L.; Teer, J.K.; Thompson, Z.J.; E Engel, B.; Xie, M.; E Berglund, A.; Creelan, B.C.; et al. Differential association of STK11 and TP53 with KRAS mutation-associated gene expression, proliferation and immune surveillance in lung adenocarcinoma. Oncogene 2015, 35, 3209–3216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.H.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. Regularization Paths for Generalized Linear Models via Coordinate Descent. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 33, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogensen, U.B.; Ishwaran, H.; Gerds, T.A. Evaluating Random Forests for Survival Analysis Using Prediction Error Curves. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 50, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshihara, K.; Shahmoradgoli, M.; Martínez, E.; Vegesna, R.; Kim, H.; Torres-Garcia, W.; Treviño, V.; Shen, H.; Laird, P.W.; Levine, D.A.; et al. Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune cell admixture from expression data. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoentong, P.; Finotello, F.; Angelova, M.; Mayer, C.; Efremova, M.; Rieder, D.; Hackl, H.; Trajanoski, Z. Pan-cancer Immunogenomic Analyses Reveal Genotype-Immunophenotype Relationships and Predictors of Response to Checkpoint Blockade. Cell Rep. 2017, 18, 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Khodadoust, M.S.; Liu, C.L.; Newman, A.M.; Alizadeh, A.A. Profiling Tumor Infiltrating Immune Cells with CIBERSORT. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018, 1711, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Gu, S.; Pan, D.; Fu, J.; Sahu, A.; Hu, X.; Li, Z.; Traugh, N.; Bu, X.; Li, B.; et al. Signatures of T cell dysfunction and exclusion predict cancer immunotherapy response. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1550–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeser, D.; Gruener, R.F.; Huang, R.S. oncoPredict: An R package for predicting in vivo or cancer patient drug response and biomarkers from cell line screening data. Briefings Bioinform. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Sun, D.; Hu, J.; Chen, Y.; Sun, L.; Yu, H.; Xiong, Y.; Huang, Z.; Xia, H.; Zhu, X.; et al. Multi-omic profiling highlights factors associated with resistance to immuno-chemotherapy in non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat. Genet. 2024, 57, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, N.S.; Nabet, B.Y.; Müller, S.; Koeppen, H.; Zou, W.; Giltnane, J.; Au-Yeung, A.; Srivats, S.; Cheng, J.H.; Takahashi, C.; et al. Intratumoral plasma cells predict outcomes to PD-L1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Cell 2022, 40, 289–300.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deepika, B.; Janani, G.; Mercy, D.J.; Udayakumar, S.; Girigoswami, A.; Girigoswami, K. Inhibitory Effect of Nano-Formulated Extract of Passiflora incarnata on Dalton’s Lymphoma Ascites-Bearing Swiss albino Mice. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrechts, D.; Wauters, E.; Boeckx, B.; Aibar, S.; Nittner, D.; Burton, O.; Bassez, A.; Decaluwé, H.; Pircher, A.; Van den Eynde, K.; et al. Phenotype molding of stromal cells in the lung tumor microenvironment. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1277–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Wang, Y.; Dong, X.; Sun, D.; Liu, Z.; Yue, J.; Wang, H.; Li, T.; Wang, C. TISCH2: Expanded datasets and new tools for single-cell transcriptome analyses of the tumor microenvironment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 51, D1425–D1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meher, R.K.; Mir, S.A.; Anisetti, S.S. In silico and in vitro investigation of dual targeting Prima-1 MET as precision therapeutic against lungs cancer. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 42, 4169–4184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelstein, B.; Papadopoulos, N.; Velculescu, V.E.; Zhou, S.; Diaz, L.A., Jr.; Kinzler, K.W. Cancer Genome Landscapes. Science 2013, 339, 1546–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trastulla, L.; Savino, A.; Beltrao, P.; Ciriano, I.C.; Fenici, P.; Garnett, M.J.; Guerini, I.; Bigas, N.L.; Mattaj, I.; Petsalaki, E.; et al. Highlights from the 1st European cancer dependency map symposium and workshop. FEBS Lett. 2023, 597, 1921–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, H.; Jiang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Li, F.; Zhang, Z. Serine related gene CCT6A promotes metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma via interacting with RPS3. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2024, 24, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.-K.; Yu, T.; Wang, Y.-M.; Sun, A.; Liu, J.; Lu, K.-H. CCT6A facilitates lung adenocarcinoma progression and glycolysis via STAT1/HK2 axis. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, W. Chaperonin containing TCP1 subunit 6A may activate Notch and Wnt pathways to facilitate the malignant behaviors and cancer stemness in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2023, 25, 2287122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Cao, J.; Liu, T.; Li, B.; Wang, J.; Pan, S.; Guo, D.; Tao, Z.; Hu, X. Chaperonin-containing TCP1 subunit 6A inhibition via TRIM21-mediated K48-linked ubiquitination suppresses triple-negative breast cancer progression through the AKT signalling pathway. Clin. Transl. Med. 2024, 14, e70097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, L.; Su, B.; Xu, L.; Hu, Z.; Li, H.; Du, H.; Li, J. MCM7 supports the stemness of bladder cancer stem-like cells by enhancing autophagic flux. iScience 2022, 25, 105029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Ho, J.-N.; Jin, H.; Lee, S.C.; Hong, S.-K.; Lee, J.W.; Lee, E.-S.; Byun, S.-S. Upregulated expression of BCL2, MCM7, and CCNE1 indicate cisplatin-resistance in the set of two human bladder cancer cell lines: T24 cisplatin sensitive and T24R2 cisplatin resistant bladder cancer cell lines. Investig. Clin. Urol. 2016, 57, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D. MCM7 affects the cisplatin resistance of liver cancer cells and the development of liver cancer by regulating the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2021, 44, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, W.; Liang, H.; Shan, S.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Q. HSPE1 Inhibits Bladder Cancer Ferroptosis via a Glutathione-Dependent Mechanism by Suppressing GPX4. Am. J. Men’s Heal. 2024, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.; Li, M. HSPE1 enhances aerobic glycolysis to promote progression of lung adenocarcinoma. Mutat. Res. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2024, 829, 111867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Gao, X.; Zheng, W.; Zhang, J. Potential impact of epithelial splicing regulatory protein 1 (ESRP1) associated with tumor immunity in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J. Proteom. 2024, 308, 105277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.-H.; Zhang, Z.-Y.; Che, C.-L.; Mei, Y.-F.; Shi, Y.-Z. Array analysis for potential biomarker of gemcitabine identification in non-small cell lung cancer cell lines. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2013, 6, 1734-46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xiong, W.; Zhang, B.; Yu, H.; Zhu, L.; Yi, L.; Jin, X. RRM2 Regulates Sensitivity to Sunitinib and PD-1 Blockade in Renal Cancer by Stabilizing ANXA1 and Activating the AKT Pathway. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2100881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Li, L.; Wu, Y.; Luo, T.; Tang, C.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Wu, J.; Lai, Y.; Zhu, D.; et al. The key cellular senescence related molecule RRM2 regulates prostate cancer progression and resistance to docetaxel treatment. Cell Biosci. 2023, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Xiang, X.; Li, W.; Yang, Q.; Yu, H.; Liu, T. RRM2 promotes liver metastasis of pancreatic cancer by stabilizing YBX1 and activating the TGF-beta pathway. iScience 2024, 27, 110864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, M.-S.; Ling, H.H.; Setiawan, S.A.; Hardianti, M.S.; Fong, I.-H.; Yeh, C.-T.; Chen, J.-H. Therapeutic targeting of thioredoxin reductase 1 causes ferroptosis while potentiating anti-PD-1 efficacy in head and neck cancer. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2024, 395, 111004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliaki, S.; Beyaert, R.; Afonina, I.S. Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) signaling in cancer and beyond. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2021, 193, 114747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Cheng, L.; Li, J.; Qiao, Q.; Karki, A.; Allison, D.B.; Shaker, N.; Li, K.; Utturkar, S.M.; Lanman, N.M.A.; et al. Targeting Plk1 Sensitizes Pancreatic Cancer to Immune Checkpoint Therapy. Cancer Res. 2022, 82, 3532–3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Zotano, Á.; Belli, S.; Zielinski, C.; Gil-Gil, M.; Fernandez-Serra, A.; Ruiz-Borrego, M.; Gil, E.M.C.; Pascual, J.; Muñoz-Mateu, M.; Bermejo, B.; et al. CCNE1 and PLK1 Mediate Resistance to Palbociclib in HR+/HER2− Metastatic Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 1557–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, J.C.; Varkaris, A.; Croucher, P.J.; Ridinger, M.; Dalrymple, S.; Nouri, M.; Xie, F.; Varmeh, S.; Jonas, O.; Whitman, M.A.; et al. Plk1 Inhibitors and Abiraterone Synergistically Disrupt Mitosis and Kill Cancer Cells of Disparate Origin Independently of Androgen Receptor Signaling. Cancer Res. 2022, 83, 219–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-J.; You, G.-R.; Lai, M.-Y.; Lu, L.-S.; Chen, C.-Y.; Ting, L.-L.; Lee, H.-L.; Kanno, Y.; Chiou, J.-F.; Cheng, A.-J. A Combined Systemic Strategy for Overcoming Cisplatin Resistance in Head and Neck Cancer: From Target Identification to Drug Discovery. Cancers 2020, 12, 3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Chen, H.; Yang, H.; Dai, H. SPC25 upregulation increases cancer stem cell properties in non-small cell lung adenocarcinoma cells and independently predicts poor survival. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 100, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Xie, L.; Lin, B.; Su, X.; Liang, R.; Ma, Z.; Li, Y. Mechanism Study of E2F8 Activation of SPC25-Mediated Glutamine Metabolism Promoting Immune Escape in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Immunology 2025, 174, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Yang, M.; Zhang, W.; Shi, D.; Li, Y.; He, L.; Huang, S.; Chen, B.; Chen, X.; Kong, L.; et al. Targeting the SPC25/RIOK1/MYH9 Axis to Overcome Tumor Stemness and Platinum Resistance in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2406688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, J.M.; Marabelle, A.; Eggermont, A.; Soria, J.-C.; Kroemer, G.; Zitvogel, L. Targeting the tumor microenvironment: Removing obstruction to anticancer immune responses and immunotherapy. Ann. Oncol. 2016, 27, 1482–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characters | Level | TCGA | GSE68465 | GSE72094 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 464 | 439 | 386 | |

| Gender | Male | 212 | 221 | 168 |

| Female | 252 | 218 | 218 | |

| Age (year) | <65 | 207 | 213 | 104 |

| >=65 | 257 | 226 | 282 | |

| T stage | T1 | 159 | 150 | NA |

| T2 | 243 | 248 | NA | |

| T3 | 42 | 29 | NA | |

| T4 | 17 | 11 | NA | |

| Tx | 3 | NA | NA | |

| N stage | N0 | 301 | 287 | NA |

| N1 | 84 | 87 | NA | |

| N2 | 67 | 52 | NA | |

| N3 | 2 | NA | NA | |

| Nx | 10 | 1 | NA | |

| M stage | M0 | 303 | NA | NA |

| M1 | 24 | NA | NA | |

| Mx | 134 | NA | NA | |

| Missing | 3 | NA | NA | |

| Pathologic stage | I | 253 | NA | 246 |

| II | 108 | NA | 65 | |

| III | 78 | NA | 56 | |

| IV | 25 | NA | 14 | |

| Missing | NA | NA | 5 | |

| Race | White | 362 | 291 | 365 |

| Non-white | 58 | 19 | 18 | |

| Missing | 44 | 129 | 3 | |

| Smoker | Yes | NA | 297 | 291 |

| No | NA | 49 | 65 | |

| Missing | NA | 93 | 30 | |

| Histological type | Acinar cell carcinoma | 20 | NA | NA |

| Adenocarcinoma with mixed subtypes | 103 | NA | NA | |

| Adenocarcinoma, NOS | 280 | NA | NA | |

| Bronchio-alveolar carcinoma, mucinous | 4 | NA | NA | |

| Bronchiolo-alveolar adenocarcinoma, NOS | 3 | NA | NA | |

| Bronchiolo-alveolar carcinoma, non-mucinous | 14 | NA | NA | |

| Clear cell adenocarcinoma, NOS | 1 | NA | NA | |

| Micropapillary carcinoma, NOS | 2 | NA | NA | |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 11 | NA | NA | |

| Papillary adenocarcinoma, NOS | 20 | NA | NA | |

| Signet ring cell carcinoma | 1 | NA | NA | |

| Solid carcinoma, NOS | 5 | NA | NA | |

| OS status | Alive | 297 | 206 | 277 |

| Dead | 167 | 233 | 109 | |

| Treatment type | Pharmaceutical Therapy, NOS | 233 | 89 | NA |

| Radiation Therapy, NOS | 231 | 65 | NA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Tan, H.; Jiang, D. Integrating Functional Genomic Screens and Multi-Omics Data to Construct a Prognostic Model for Lung Adenocarcinoma and Validating SPC25. Cancers 2025, 17, 3844. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233844

Zhang Y, Tan H, Jiang D. Integrating Functional Genomic Screens and Multi-Omics Data to Construct a Prognostic Model for Lung Adenocarcinoma and Validating SPC25. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3844. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233844

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yang, Huijun Tan, and Depeng Jiang. 2025. "Integrating Functional Genomic Screens and Multi-Omics Data to Construct a Prognostic Model for Lung Adenocarcinoma and Validating SPC25" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3844. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233844

APA StyleZhang, Y., Tan, H., & Jiang, D. (2025). Integrating Functional Genomic Screens and Multi-Omics Data to Construct a Prognostic Model for Lung Adenocarcinoma and Validating SPC25. Cancers, 17(23), 3844. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233844