High-Throughput Molecular Characterization of the Microbiome in Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma and Peri-Implant Benign Seromas

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Nanopore Sequencing and Data Analysis

2.3. Microbiome Sequencing by 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing and Data Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

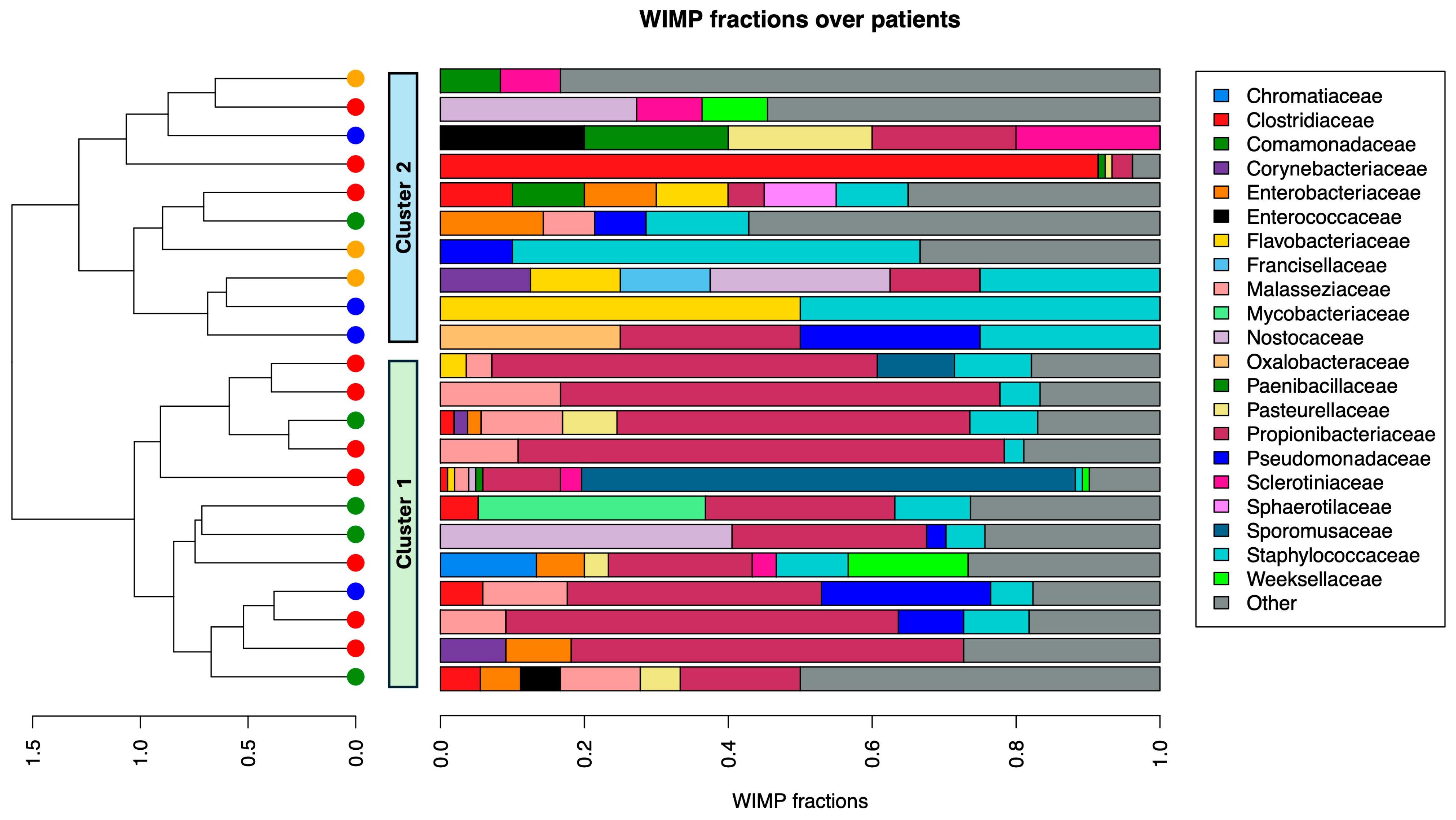

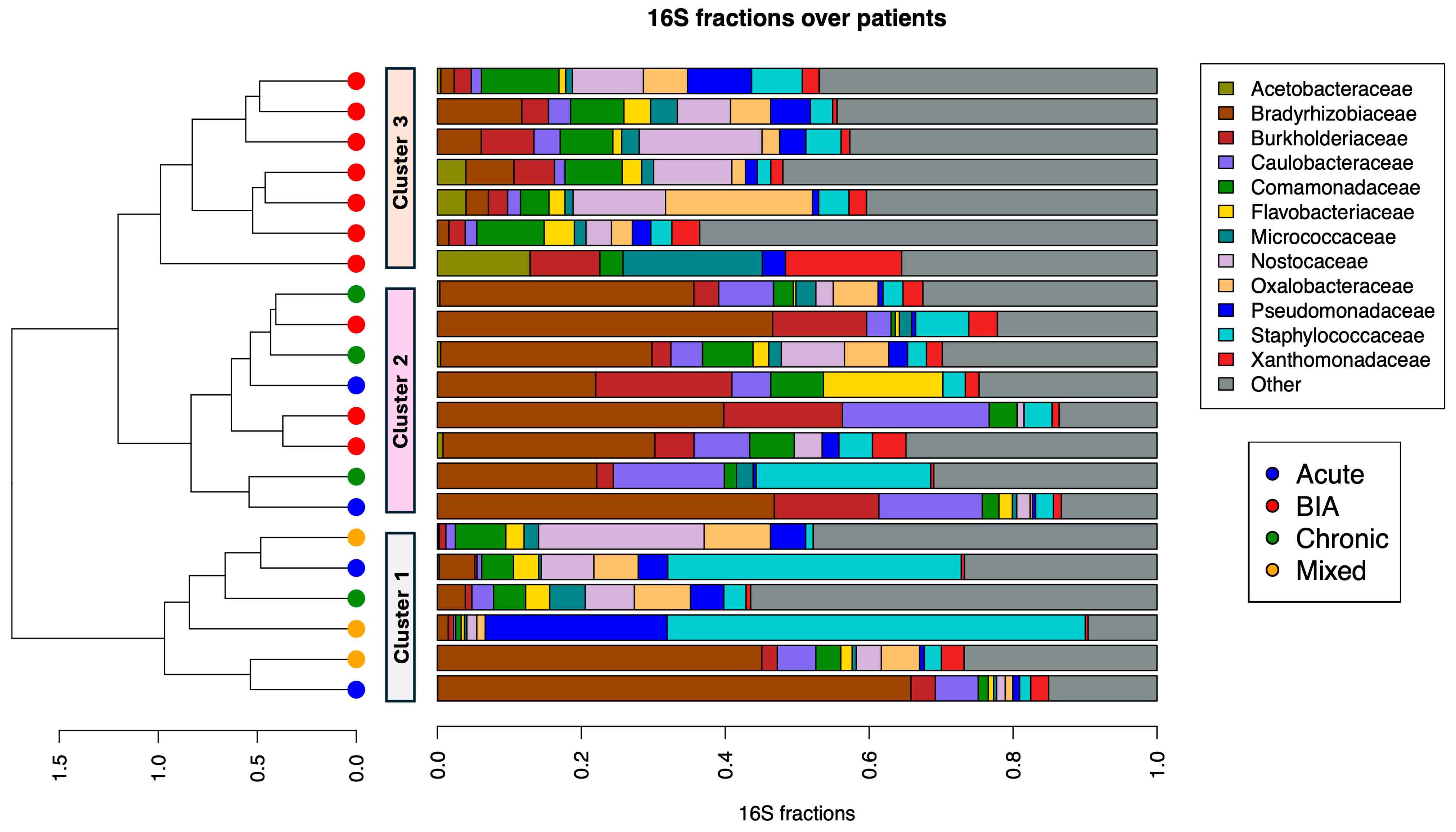

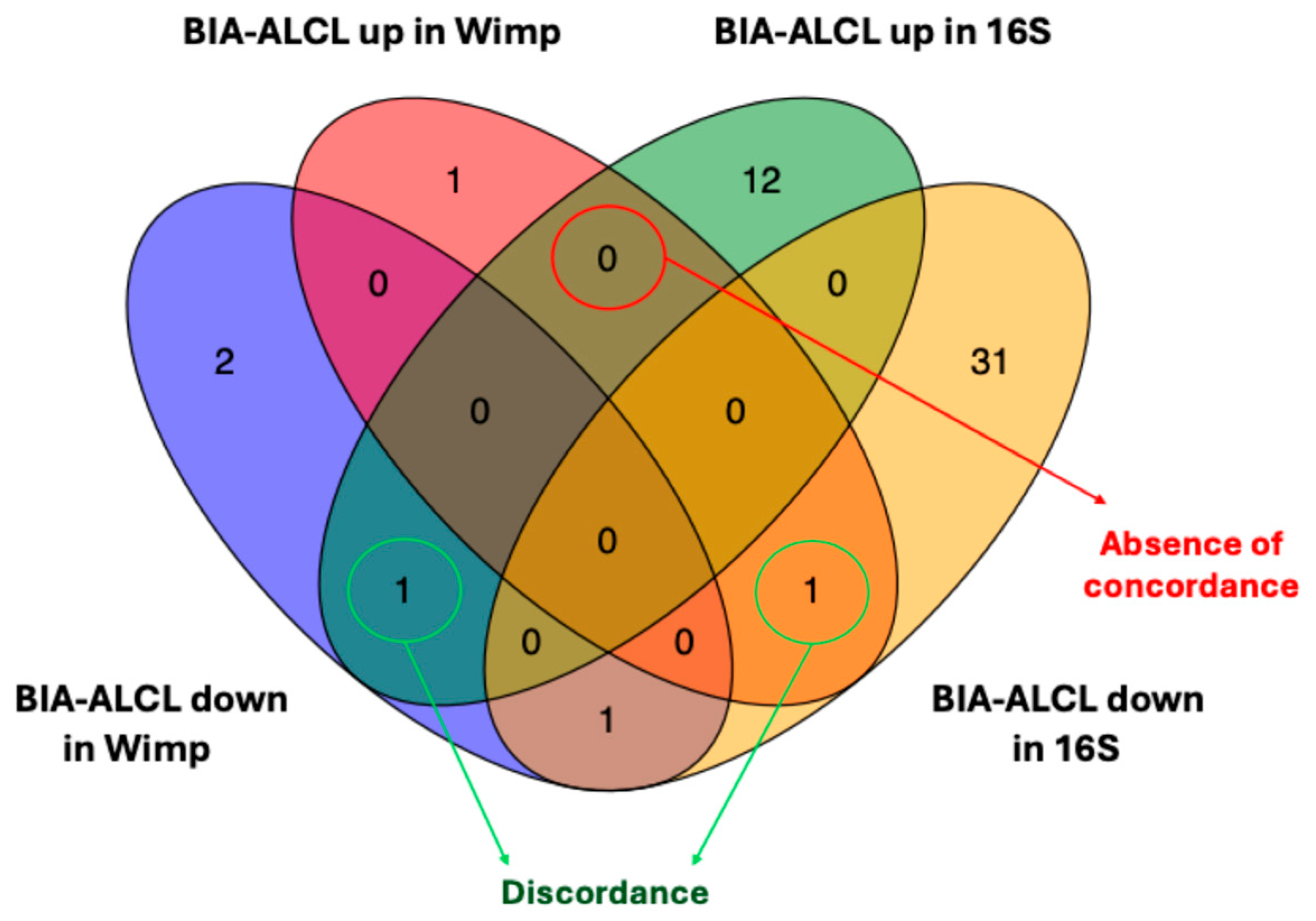

3.1. Abundance Analysis of BIA-ALCL and Benign Samples

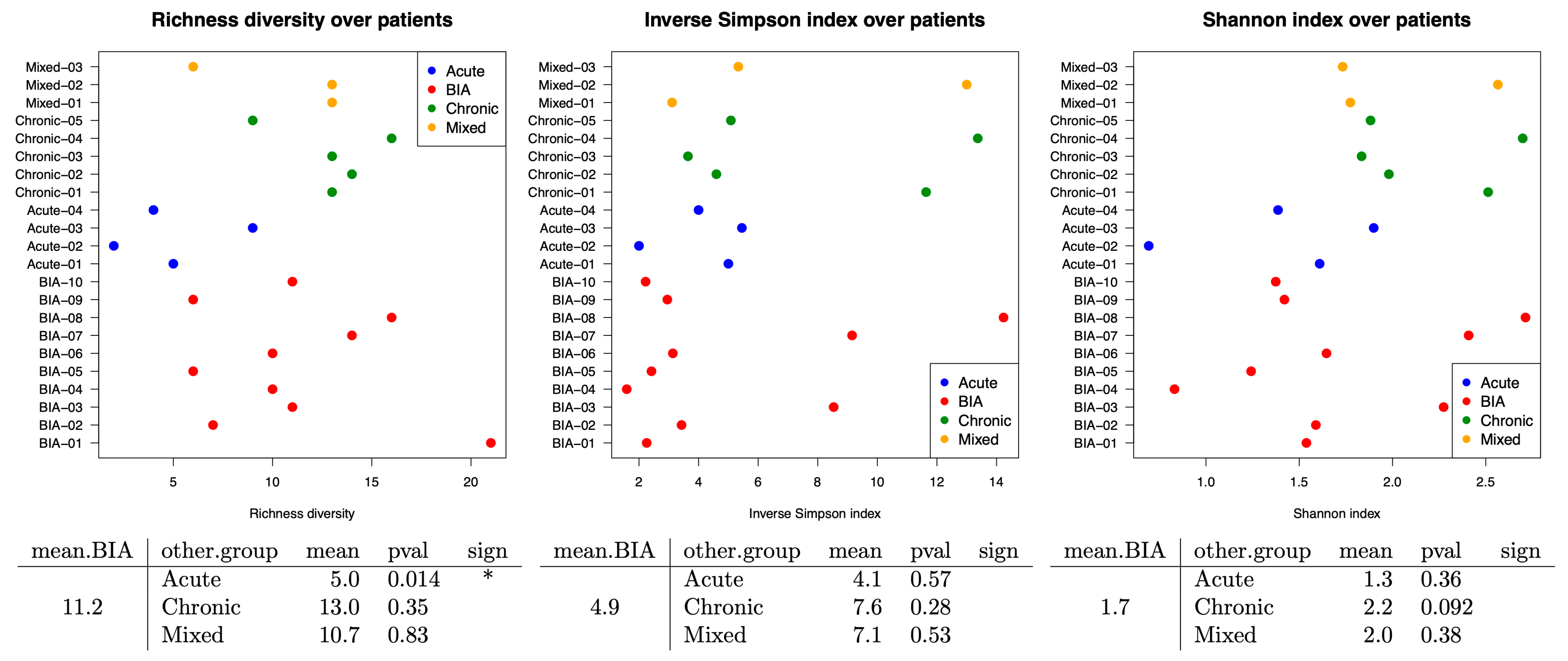

3.2. Bacterial Family Differences Within Samples by Using Alpha Diversity Assays

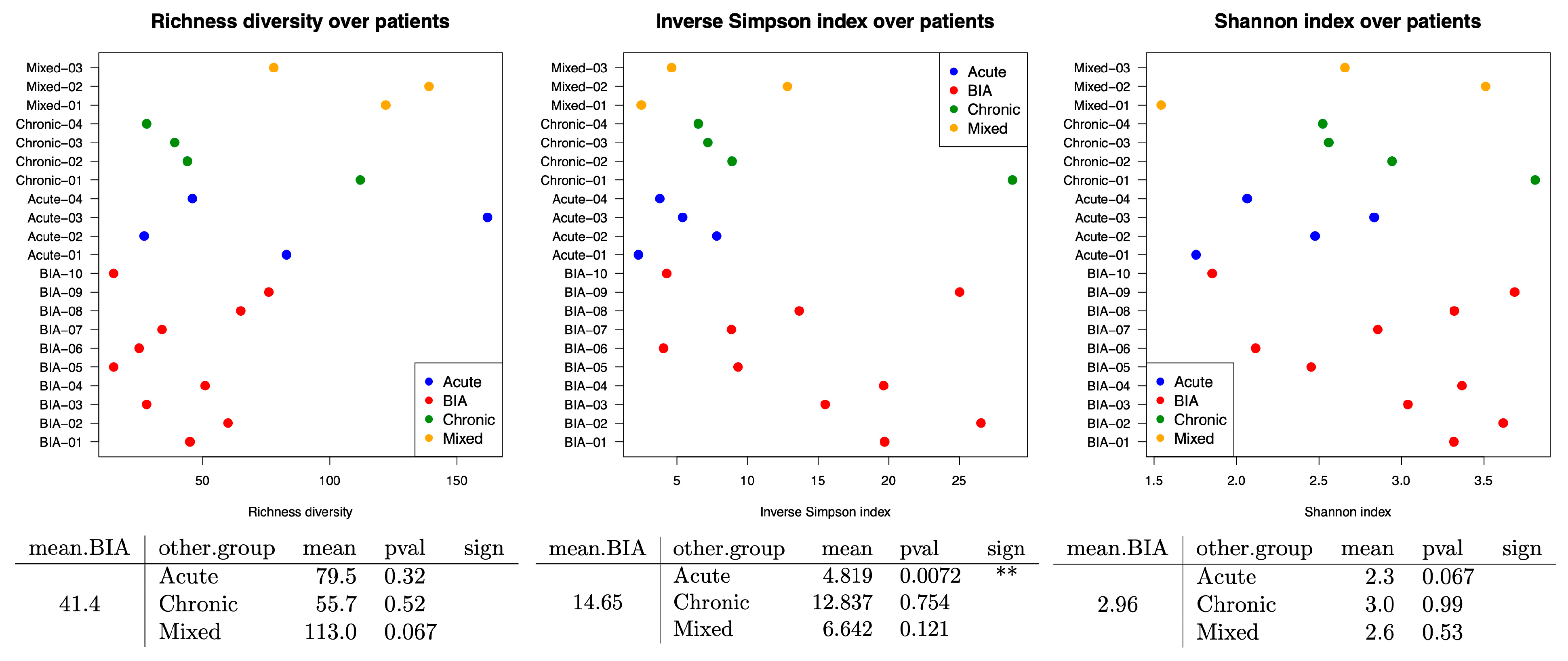

3.3. Impact of Bacteria GRAM Stain in Benign and BIA-ALCL Seromas

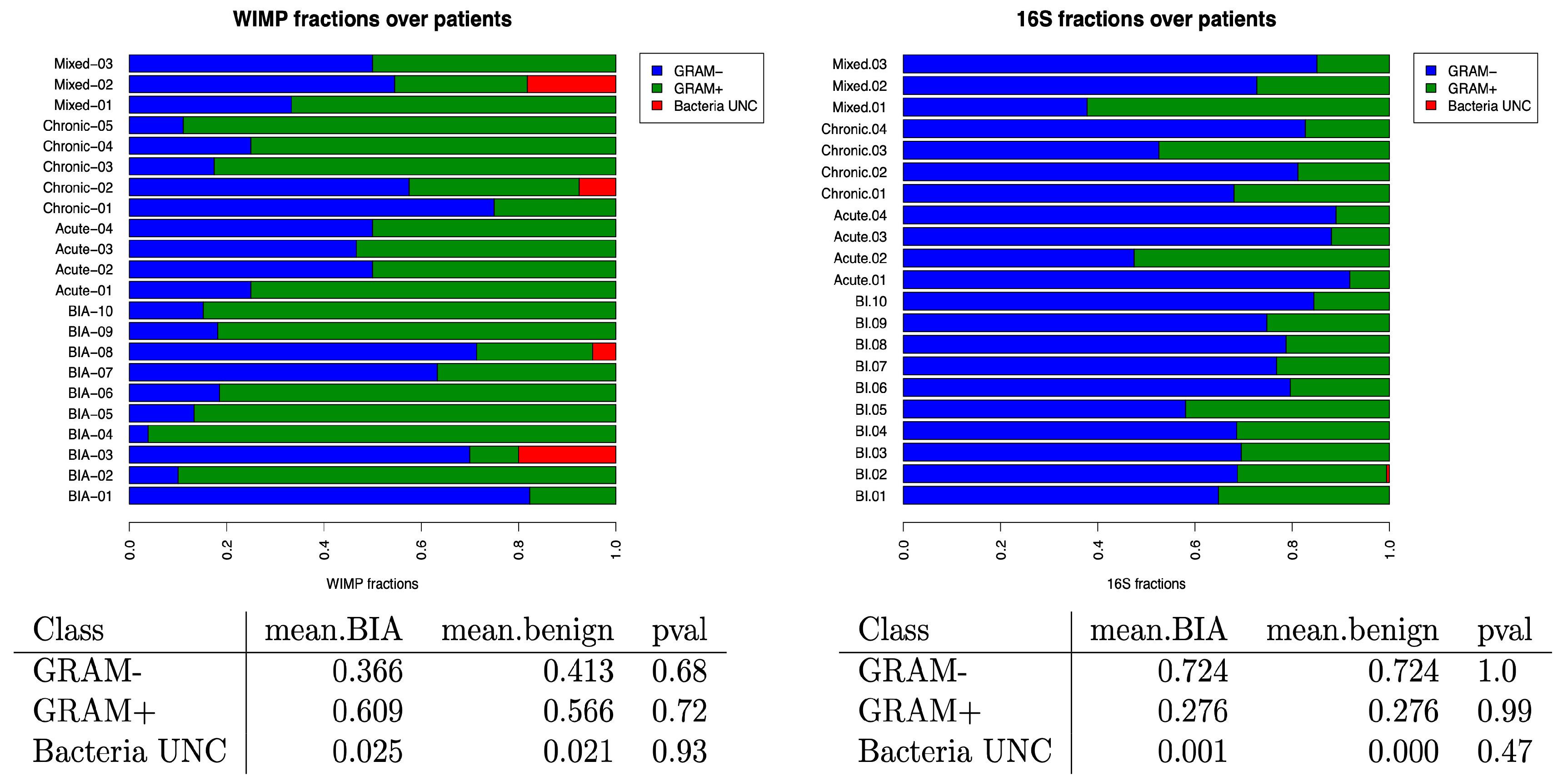

3.4. Oxygen Tolerance of the Bacteria in Benign and BIA-ALCL Seromas

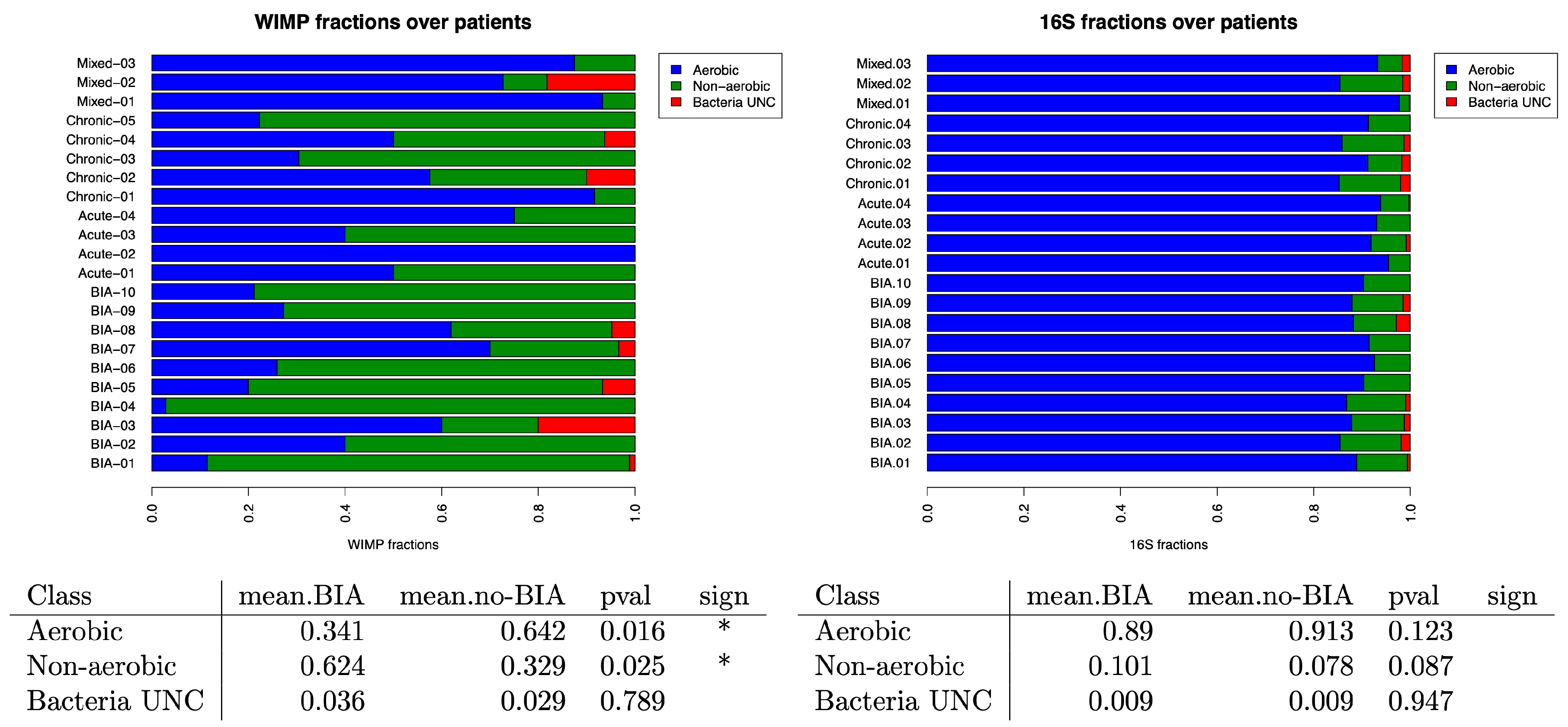

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BIA-ALCL | Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| SCHEER | Scientific Committee on Health, Emerging and Environmental Risks |

| NGS | Next Generation Sequencing |

| WIMP | What’s in my Pot? |

| ALK | Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase |

| HHV8 | Herpes Virus 8 |

| QIIME | Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology 2 |

| ANCOMBC | Analysis of Compositions of Microbiomes with Bias Correction |

| ONT | Oxford Nanopore Technologies |

| NCBI | National Center for Biotechnology Information |

References

- Alaggio, R.; Amador, C.; Anagnostopoulos, I.; Attygalle, A.D.; Araujo, I.B.d.O.; Berti, E.; Bhagat, G.; Borges, A.M.; Boyer, D.; Calaminici, M.; et al. The 5th Edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Lymphoid Neoplasms. Leukemia 2022, 36, 1720–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Medical Device Reports of Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/breast-implants/medical-device-reports-breast-implant-associated-anaplastic-large-cell-lymphoma (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Di Napoli, A.; Pepe, G.; Giarnieri, E.; Cippitelli, C.; Bonifacino, A.; Mattei, M.; Martelli, M.; Falasca, C.; Cox, M.C.; Santino, I.; et al. Cytological Diagnostic Features of Late Breast Implant Seromas: From Reactive to Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, E.S.; Ashar, B.S.; Clemens, M.W.; Feldman, A.L.; Gaulard, P.; Miranda, R.N.; Sohani, A.R.; Stenzel, T.; Yoon, S.W. Best Practices Guideline for the Pathologic Diagnosis of Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large-Cell Lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 1102–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCoster, R.C.; Clemens, M.W.; Di Napoli, A.; Lynch, E.B.; Bonaroti, A.R.; Rinker, B.D.; Butterfield, T.A.; Vasconez, H.C. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2021, 147, 30e–41e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oishi, N.; Hundal, T.; Phillips, J.L.; Dasari, S.; Hu, G.; Viswanatha, D.S.; He, R.; Mai, M.; Jacobs, H.K.; Ahmed, N.H.; et al. Molecular Profiling Reveals a Hypoxia Signature in Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma. Haematologica 2021, 106, 1714–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Napoli, A.; Jain, P.; Duranti, E.; Margolskee, E.; Arancio, W.; Facchetti, F.; Alobeid, B.; Santanelli di Pompeo, F.; Mansukhani, M.; Bhagat, G. Targeted next Generation Sequencing of Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma Reveals Mutations in JAK/STAT Signalling Pathway Genes, TP53 and DNMT3A. Br. J. Haematol. 2018, 180, 741–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blombery, P.; Thompson, E.R.; Jones, K.; Arnau, G.M.; Lade, S.; Markham, J.F.; Li, J.; Deva, A.; Johnstone, R.W.; Khot, A.; et al. Whole Exome Sequencing Reveals Activating JAK1 and STAT3 Mutations in Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma. Haematologica 2016, 101, e387–e390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oishi, N.; Brody, G.S.; Ketterling, R.P.; Viswanatha, D.S.; He, R.; Dasari, S.; Mai, M.; Benson, H.K.; Sattler, C.A.; Boddicker, R.L.; et al. Genetic Subtyping of Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma. Blood 2018, 132, 544–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letourneau, A.; Maerevoet, M.; Milowich, D.; Dewind, R.; Bisig, B.; Missiaglia, E.; de Leval, L. Dual JAK1 and STAT3 Mutations in a Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma. Virchows Arch. 2018, 473, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, C.; Nicolae, A.; Laurent, C.; Le Bras, F.; Haioun, C.; Fataccioli, V.; Amara, N.; Adélaïde, J.; Guille, A.; Schiano, J.-M.; et al. Gene Alterations in Epigenetic Modifiers and JAK-STAT Signaling Are Frequent in Breast Implant-Associated ALCL. Blood 2020, 135, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Los-de Vries, G.T.; de Boer, M.; van Dijk, E.; Stathi, P.; Hijmering, N.J.; Roemer, M.G.M.; Mendeville, M.; Miedema, D.M.; de Boer, J.P.; Rakhorst, H.A.; et al. Chromosome 20 Loss Is Characteristic of Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma. Blood 2020, 136, 2927–2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quesada, A.E.; Zhang, Y.; Ptashkin, R.; Ho, C.; Horwitz, S.; Benayed, R.; Dogan, A.; Arcila, M.E. Next Generation Sequencing of Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphomas Reveals a Novel STAT3-JAK2 Fusion among Other Activating Genetic Alterations within the JAK-STAT Pathway. Breast J. 2021, 27, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechner, M.G.; Megiel, C.; Church, C.H.; Angell, T.E.; Russell, S.M.; Sevell, R.B.; Jang, J.K.; Brody, G.S.; Epstein, A.L. Survival Signals and Targets for Therapy in Breast Implant-Associated ALK--Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 4549–4559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Napoli, A.; De Cecco, L.; Piccaluga, P.P.; Navari, M.; Cancila, V.; Cippitelli, C.; Pepe, G.; Lopez, G.; Monardo, F.; Bianchi, A.; et al. Transcriptional Analysis Distinguishes Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma from Other Peripheral T-Cell Lymphomas. Mod. Pathol. 2019, 32, 216–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14607:2024; Non-Active Surgical Implants—Mammary Implants—Particular Requirements. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- SCHEER—Scientific Committee on Health, Environmental and Emerging Risks. Scientific Opinion on the Safety of Breast Implants in Relation to Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Doloff, J.C.; Veiseh, O.; de Mezerville, R.; Sforza, M.; Perry, T.A.; Haupt, J.; Jamiel, M.; Chambers, C.; Nash, A.; Aghlara-Fotovat, S.; et al. The Surface Topography of Silicone Breast Implants Mediates the Foreign Body Response in Mice, Rabbits and Humans. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 5, 1115–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santanelli di Pompeo, F.; Sorotos, M.; Canese, R.; Valeri, M.; Roberto, C.; Giorgia, S.; Firmani, G.; di Napoli, A. Study of the Effect of Different Breast Implant Surfaces on Capsule Formation and Host Inflammatory Response in an Animal Model. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2023, 43, 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Jacombs, A.; Vickery, K.; Merten, S.L.; Pennington, D.G.; Deva, A.K. Chronic Biofilm Infection in Breast Implants Is Associated with an Increased T-Cell Lymphocytic Infiltrate: Implications for Breast Implant-Associated Lymphoma. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2015, 135, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mempin, M.; Hu, H.; Chowdhury, D.; Deva, A.; Vickery, K. The A, B and C’s of Silicone Breast Implants: Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma, Biofilm and Capsular Contracture. Materials 2018, 11, 2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, G.A.; Boegli, L.; Hancock, J.; Bowersock, L.; Parker, A.; Kinney, B.M. Bacterial Adhesion and Biofilm Formation on Textured Breast Implant Shell Materials. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2019, 43, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezende-Pereira, G.; Albuquerque, J.P.; Souza, M.C.; Nogueira, B.A.; Silva, M.G.; Hirata, R.; Mattos-Guaraldi, A.L.; Duarte, R.S.; Neves, F.P.G. Biofilm Formation on Breast Implant Surfaces by Major Gram-Positive Bacterial Pathogens. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2021, 41, 1144–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Mempin, M.; Hu, H.; Chowdhury, D.; Foley, M.; Cooter, R.; Adams, W.P.; Vickery, K.; Deva, A.K. The Functional Influence of Breast Implant Outer Shell Morphology on Bacterial Attachment and Growth. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2018, 142, 837–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chessa, D.; Ganau, G.; Spiga, L.; Bulla, A.; Mazzarello, V.; Campus, G.V.; Rubino, S. Staphylococcus Aureus and Staphylococcus Epidermidis Virulence Strains as Causative Agents of Persistent Infections in Breast Implants. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mempin, M.; Hu, H.; Vickery, K.; Kadin, M.E.; Prince, H.M.; Kouttab, N.; Morgan, J.W.; Adams, W.P.; Deva, A.K. Gram-Negative Bacterial Lipopolysaccharide Promotes Tumor Cell Proliferation in Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large-Cell Lymphoma. Cancers 2021, 13, 5298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Johani, K.; Almatroudi, A.; Vickery, K.; Van Natta, B.; Kadin, M.E.; Brody, G.; Clemens, M.; Cheah, C.Y.; Lade, S.; et al. Bacterial Biofilm Infection Detected in Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large-Cell Lymphoma. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2016, 137, 1659–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, J.N.; Hanson, B.M.; Pinkner, C.L.; Simar, S.R.; Pinkner, J.S.; Parikh, R.; Clemens, M.W.; Hultgren, S.J.; Myckatyn, T.M. Insights into the Microbiome of Breast Implants and Periprosthetic Tissue in Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemens, M.W.; Medeiros, L.J.; Butler, C.E.; Hunt, K.K.; Fanale, M.A.; Horwitz, S.; Weisenburger, D.D.; Liu, J.; Morgan, E.A.; Kanagal-Shamanna, R.; et al. Complete Surgical Excision Is Essential for the Management of Patients With Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large-Cell Lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanoporetech Oxford Nanopore Technologies. Available online: https://nanoporetech.com/document/experiment-companion-minknow (accessed on 26 August 2020).

- EPI2ME. Available online: https://epi2me.nanoporetech.com/about/ (accessed on 26 August 2020).

- RefSeq: NCBI Reference Sequence Database. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/refseq (accessed on 26 August 2020).

- Solcova, M.; Demnerova, K.; Purkrtova, S. Application of Nanopore Sequencing (MinION) for the Analysis of Bacteriome and Resistome of Bean Sprouts. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechan Llontop, M.E.; Sharma, P.; Aguilera Flores, M.; Yang, S.; Pollok, J.; Tian, L.; Huang, C.; Rideout, S.; Heath, L.S.; Li, S.; et al. Strain-Level Identification of Bacterial Tomato Pathogens Directly from Metagenomic Sequences. Phytopathology 2020, 110, 768–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maguire, M.; Kase, J.A.; Roberson, D.; Muruvanda, T.; Brown, E.W.; Allard, M.; Musser, S.M.; González-Escalona, N. Precision Long-Read Metagenomics Sequencing for Food Safety by Detection and Assembly of Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia Coli in Irrigation Water. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, S.A.; Szöcs, E. Taxize: Taxonomic Search and Retrieval in R. F1000Research 2013, 2, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, L.; Borro, M.; Milani, C.; Simmaco, M.; Esposito, G.; Canali, G.; Pilozzi, E.; Ventura, M.; Annibale, B.; Lahner, E. Gastric Microbiota Composition in Patients with Corpus Atrophic Gastritis. Dig. Liver Dis. 2021, 53, 1580–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Peddada, S.D. Analysis of Compositions of Microbiomes with Bias Correction. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, E. Measurement of Diversity. Nature 1949, 163, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spellerberg, I.F.; Fedor, P.J. A Tribute to Claude Shannon (1916–2001) and a Plea for More Rigorous Use of Species Richness, Species Diversity and the “Shannon–Wiener” Index. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2003, 12, 177–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Statistical Software; v4.5.0. The R Project for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria. Available online: http://www.R-project.org (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Schober, I.; Koblitz, J.; Sardà Carbasse, J.; Ebeling, C.; Schmidt, M.L.; Podstawka, A.; Gupta, R.; Ilangovan, V.; Chamanara, J.; Overmann, J.; et al. BacDive in 2025: The Core Database for Prokaryotic Strain Data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D748–D756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UK Health Security Agency, Culture Collection. Available online: https://www.culturecollections.org.uk (accessed on 26 August 2020).

- Cébron, A.; Zeghal, E.; Usseglio-Polatera, P.; Meyer, A.; Bauda, P.; Lemmel, F.; Leyval, C.; Maunoury-Danger, F. BactoTraits—A Functional Trait Database to Evaluate How Natural and Man-Induced Changes Influence the Assembly of Bacterial Communities. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 130, 108047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessler, M.; Neumann, J.S.; Afshinnekoo, E.; Pineda, M.; Hersch, R.; Velho, L.F.M.; Segovia, B.T.; Lansac-Toha, F.A.; Lemke, M.; DeSalle, R.; et al. Large-Scale Differences in Microbial Biodiversity Discovery between 16S Amplicon and Shotgun Sequencing. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, R.H.; Glendinning, L.; Walker, A.W.; Watson, M. Investigating the Impact of Database Choice on the Accuracy of Metagenomic Read Classification for the Rumen Microbiome. Anim. Microbiome 2022, 4, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sczyrba, A.; Hofmann, P.; Belmann, P.; Koslicki, D.; Janssen, S.; Dröge, J.; Gregor, I.; Majda, S.; Fiedler, J.; Dahms, E.; et al. Critical Assessment of Metagenome Interpretation-a Benchmark of Metagenomics Software. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 1063–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CASE ID | Type of Seroma | Age | Reason of the Implant |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute-01 | Acute | 42 | Aesthetic |

| Acute-02 | Acute | 43 | Reconstruction after breast cancer |

| Acute-03 | Acute | 59 | Reconstruction after breast cancer |

| Acute-04 | Acute | 33 | Aesthetic |

| Mixed-01 | Mixed | 56 | Aesthetic |

| Mixed-02 | Mixed | 50 | Reconstruction after breast cancer |

| Mixed-03 | Mixed | 63 | Aesthetic |

| Chronic-01 | Chronic | 60 | Reconstruction after breast cancer |

| Chronic-02 | Chronic | 38 | Aesthetic |

| Chronic-03 | Chronic | 69 | Reconstruction after breast cancer |

| Chronic-04 | Chronic | 69 | Reconstruction after breast cancer |

| Chronic-05 | Chronic | 52 | Reconstruction after breast cancer |

| CASE ID | Age (Years) | Reason of the Implant | Time from the Implant (Years) | MD Anderson Stage | Therapy | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIA-01 | 53 | Aesthetic | 3 | IA | Radical en-bloc capsulectomy | CR |

| BIA-02 | 67 | Reconstruction after breast cancer | 13 | IIA | Radical en-bloc Capsulectomy+RT | CR |

| BIA-03 | 66 | Reconstruction after breast cancer | 11 | IIB | Radical en-bloc capsulectomy+CHOEP | CR |

| BIA-04 | 55 | Aesthetic | 10 | IA | Radical en-bloc capsulectomy | CR |

| BIA-05 | 49 | Reconstruction after breast cancer | 8 | IA | Radical en-bloc capsulectomy | CR |

| BIA-06 | 76 | Reconstruction after breast cancer | 15 | IIA | Radical en-bloc capsulectomy+RT | CR |

| BIA-07 | 54 | Reconstruction after breast cancer | 13 | IA | Radical en-bloc capsulectomy | CR |

| BIA-08 | 51 | Reconstruction after breast cancer | NA | IB | Radical en-bloc capsulectomy | CR |

| BIA-09 | 40 | Aesthetic | 12 | IA | Radical en-bloc capsulectomy | CR |

| BIA-10 | 38 | Aesthetic | 6 | IA | Radical en-bloc capsulectomy | CR |

| Sample Type | Microorganisms (Total n) | Bacterial Families (n) | Fungal Families (n) | Viral Families (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIA-ALCL | 63 | 55 | 4 | 4 |

| Benign seroma | 65 | 56 | 6 | 3 |

| Acute-type | 15 | 12 | 2 | 1 |

| Mixed-type | 29 | 26 | 2 | 1 |

| Chronic-type | 43 | 37 | 4 | 2 |

| Sample Type | Bacterial Families (n) |

|---|---|

| BIA-ALCL | 130 |

| Benign seroma | 212 |

| Acute-type | 175 |

| Mixed-type | 180 |

| Chronic-type | 119 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rogges, E.; Bertolazzi, G.; Vacca, D.; Borro, M.; Lopez, G.; Simmaco, M.; Scattone, A.; Firmani, G.; Sorotos, M.; Santanelli di Pompeo, F.; et al. High-Throughput Molecular Characterization of the Microbiome in Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma and Peri-Implant Benign Seromas. Cancers 2025, 17, 3839. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233839

Rogges E, Bertolazzi G, Vacca D, Borro M, Lopez G, Simmaco M, Scattone A, Firmani G, Sorotos M, Santanelli di Pompeo F, et al. High-Throughput Molecular Characterization of the Microbiome in Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma and Peri-Implant Benign Seromas. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3839. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233839

Chicago/Turabian StyleRogges, Evelina, Giorgio Bertolazzi, Davide Vacca, Marina Borro, Gianluca Lopez, Maurizio Simmaco, Anna Scattone, Guido Firmani, Michail Sorotos, Fabio Santanelli di Pompeo, and et al. 2025. "High-Throughput Molecular Characterization of the Microbiome in Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma and Peri-Implant Benign Seromas" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3839. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233839

APA StyleRogges, E., Bertolazzi, G., Vacca, D., Borro, M., Lopez, G., Simmaco, M., Scattone, A., Firmani, G., Sorotos, M., Santanelli di Pompeo, F., Noccioli, N., Savino, E., Vecchione, A., & Di Napoli, A. (2025). High-Throughput Molecular Characterization of the Microbiome in Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma and Peri-Implant Benign Seromas. Cancers, 17(23), 3839. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233839