Performance of GAAD and GALAD Biomarker Panels for HCC Detection in Patients with MASLD or ALD Cirrhosis

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Sample Processing and Biomarker Measurement

2.3. Ultrasound Assessment

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Individual Biomarkers

3.3. GAAD and GALAD

3.4. Abdominal Ultrasound

3.5. GAAD vs. Ultrasound Plus AFP

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rumgay, H.; Arnold, M.; Ferlay, J.; Lesi, O.; Cabasag, C.J.; Vignat, J.; Laversanne, M.; McGlynn, K.A.; Soerjomataram, I. Global burden of primary liver cancer in 2020 and predictions to 2040. J. Hepatol. 2022, 77, 1598–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2018, 69, 182–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singal, A.G.; Llovet, J.M.; Yarchoan, M.; Mehta, N.; Heimbach, J.K.; Dawson, L.A.; Jou, J.H.; Kulik, L.M.; Agopian, V.G.; Marrero, J.A.; et al. AASLD Practice Guidance on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2023, 78, 1922–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, N.; Schoenberger, H.; Yekkaluri, S.; Fetzer, D.T.; Rich, N.E.; Yokoo, T.; Gopal, P.; Manwaring, C.; Quirk, L.; Singal, A.G. Association between ultrasound quality and test performance for HCC surveillance in patients with cirrhosis: A retrospective cohort study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 55, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzartzeva, K.; Obi, J.; Rich, N.E.; Parikh, N.D.; Marrero, J.A.; Yopp, A.; Waljee, A.K.; Singal, A.G. Surveillance Imaging and Alpha Fetoprotein for Early Detection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients with Cirrhosis: A Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2018, 154, 1706–1718.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samoylova, M.L.; Mehta, N.; Roberts, J.P.; Yao, F.Y. Predictors of Ultrasound Failure to Detect Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Liver Transpl. 2018, 24, 1171–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.K.; Lee, D.H.; Hur, B.Y.; Lee, H.-C.; Bin Lee, Y.; Yu, S.J.; Kim, Y.J.; Yoon, J.-H.; Lee, J.-H. Effectiveness of US Surveillance of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Chronic Hepatitis B: US LI-RADS Visualization Score. Radiology 2023, 307, e222106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.H.; Kim, N.H.; Kim, D.H.; Choi, Y.; Choi, J.-I. Ultrasound LI-RADS Visualization Scores on Surveillance Ultrasound for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Systematic Review with Meta-analysis. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2023, 49, 2205–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiyarattanachai, T.; Fetzer, D.T.; Kamaya, A. Multicenter Study of ACR Ultrasound LI-RADS Visualization Scores on Serial Examinations: Implications for Surveillance Strategies. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2022, 219, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimman, M.; Hernaez, R.; Cerda, V.; Lee, M.; Yekkaluri, S.; Khan, A.; Sood, A.; Gurley, T.; Quirk, L.; Liu, Y.; et al. Financial Burden of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Screening in Patients with Cirrhosis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 22, 760–767.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narasimman, M.; Hernaez, R.; Cerda, V.; Lee, M.; Sood, A.; Yekkaluri, S.; Khan, A.; Quirk, L.; Liu, Y.; Kramer, J.R.; et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance may be associated with potential psychological harms in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 2023, 79, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, E.; Rich, N.E.; Marrero, J.A.; Parikh, N.D.; Singal, A.G. Use of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Surveillance in Patients with Cirrhosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Hepatology 2020, 73, 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teerasarntipan, T.M.; Sritunyarat, Y.M.; Prathyajuta, P.; Pitakkitnukun, P.; Phathong, C.M.; Ariyaskul, D.; Kulkraisri, K.; Tangkijvanich, P.; Treeprasertsuk, S.; Rerknimitr, R.; et al. Physician- and patient-reported barriers to hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance: A nationwide survey. Medicine 2022, 101, e30538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, S.-S.; Hu, H.-Y.; Cheng, F.-S.M.; Chen, Y.-C.M.; Yen, Y.-F.; Huang, N. Factors associated with nonadherence to surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with hepatic C virus cirrhosis, 2000–2015. Medicine 2022, 101, e31907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, H.; Kim, M.-J.; Kim, D.Y.; An, C.; Kang, W.; Han, K.; Roh, Y.H.; Han, K.-H.; Ahn, S.H.; Choi, J.-Y.; et al. Noncontrast Magnetic Resonance Imaging vs Ultrasonography for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Surveillance: A Randomized, Single-Center Trial. Gastroenterology 2025, 168, 1170–1177.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; An, J.; Lim, Y.-S.; Han, S.; Lee, J.-Y.; Byun, J.H.; Won, H.J.; Lee, S.J.; Lee, H.C.; Lee, Y.S. MRI with Liver-Specific Contrast for Surveillance of Patients with Cirrhosis at High Risk of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Jang, H.Y.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, S.J.; Won, H.J.; Byun, J.H.; Choi, S.H.; Lee, S.S.; An, J.; Lim, Y.-S. Non-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging as a surveillance tool for hepatocellular carcinoma: Comparison with ultrasound. J. Hepatol. 2020, 72, 718–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittaker, S.; Marais, R.; Zhu, A.X. The role of signaling pathways in the development and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene 2010, 29, 4989–5005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, A. Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1450–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Guo, J.; Li, W.; Lu, Y.; Fu, S.; Xie, X.; Xia, H.; Dong, X.; Chen, Y.; Quan, M.; et al. Hepatitis B virus X protein induces expression of alpha-fetoprotein and activates PI3K/mTOR signaling pathway in liver cells. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 12196–12208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, G.; Sun, G.; Cheng, Z.; Zhang, L.; Hu, K.; Xia, X.; Zhou, Y. p55PIK regulates alpha-fetoprotein expression through the NF-κB signaling pathway. Life Sci. 2017, 191, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montal, R.; Andreu-Oller, C.; Bassaganyas, L.; Esteban-Fabró, R.; Moran, S.; Montironi, C.; Moeini, A.; Pinyol, R.; Peix, J.; Cabellos, L.; et al. Molecular portrait of high alpha-fetoprotein in hepatocellular carcinoma: Implications for biomarker-driven clinical trials. Br. J. Cancer 2019, 121, 340–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piratvisuth, T.; Tanwandee, T.; Thongsawat, S.; Sukeepaisarnjaroen, W.; Esteban, J.I.; Bes, M.; Köhler, B.; He, Y.; Lange, M.S.; Morgenstern, D.; et al. Multimarker Panels for Detection of Early Stage Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Prospective, Multicenter, Case-Control Study. Hepatol. Commun. 2021, 6, 679–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrah, M.; Arvind, A.; Gopal, P.; Deodhar, S.; Yang, J.D.; Parikh, N.D.; Singal, A.G. Performance of GALAD, GAAD, and ASAP for Early HCC Detection in Chronic Liver Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Liver Cancer 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maneenil, C.; Sripongpun, P.; Chamroonkul, N.; Tantisaranon, P.; Jarumanokul, R.; Samaeng, M.; Yamsuwan, Y.; Fonghoi, L.; Numit, A.; Piratvisuth, T.; et al. Comparative performance of the GAAD and ASAP scores in predicting early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2025, 13, goaf074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berhane, S.; Toyoda, H.; Tada, T.; Kumada, T.; Kagebayashi, C.; Satomura, S.; Schweitzer, N.; Vogel, A.; Manns, M.P.; Benckert, J.; et al. Role of the GALAD and BALAD-2 Serologic Models in Diagnosis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Prediction of Survival in Patients. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 14, 875–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Fang, M.; Xiao, X.; Wang, H.; Gao, Z.; Ji, J.; Liu, L.; Gu, E.; Li, Y.; Wang, M.; et al. Validation of the GALAD model for early diagnosis and monitoring of hepatocellular carcinoma in Chinese multicenter study. Liver Int. 2021, 42, 210–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, T.; Hou, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, D.; Li, J.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yang, D. Validation of combined AFP, AFP-L3, and PIVKA II for diagnosis and monitoring of hepatocellular carcinoma in Chinese patients. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.-Y.; Wang, N.-Y.; Diao, Y.-K.; Yan, C.-L.; Fan, Z.-P.; Wei, L.-H.; Li, H.-J.; Guan, M.-C.; Wang, M.-D.; Pawlik, T.M.; et al. Comparison between models for detecting hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic liver diseases of various etiologies: ASAP score versus GALAD score. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 2023, 24, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.D.; Addissie, B.D.; Lavu, S.; Cvinar, J.L.; Giama, N.H.; Moser, C.D.; Miyabe, K.; Allotey, L.K.; Algeciras-Schimnich, A.; Theobald, J.P.; et al. GALAD Score for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Detection in Comparison with Liver Ultrasound and Proposal of GALADUS Score. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2019, 28, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piratvisuth, T.; Hou, J.; Tanwandee, T.; Berg, T.; Vogel, A.; Trojan, J.; De Toni, E.N.; Kudo, M.; Eiblmaier, A.; Klein, H.-G.; et al. Development and clinical validation of a novel algorithmic score (GAAD) for detecting HCC in prospective cohort studies. Hepatol. Commun. 2023, 7, e0317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, J.; Bechmann, L.P.; Sowa, J.P.; Sydor, S.; Dechêne, A.; Pflanz, K.; Bedreli, S.; Schotten, C.; Geier, A.; Berg, T.; et al. GALAD Score Detects Early Hepatocellular Carcinoma in an International Cohort of Patients with Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 18, 728–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, J.; Berg, T.; Vogel, A.; Piratvisuth, T.; Trojan, J.; De Toni, E.N.; Kudo, M.; Malinowsky, K.; Findeisen, P.; Hegel, J.K.; et al. Comparative evaluation of multimarker algorithms for early-stage HCC detection in multicenter prospective studies. JHEP Rep. 2024, 7, 101263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, P.J.; Pirrie, S.J.; Cox, T.F.; Berhane, S.; Teng, M.; Palmer, D.; Morse, J.; Hull, D.; Patman, G.; Kagebayashi, C.; et al. The Detection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Using a Prospectively Developed and Validated Model Based on Serological Biomarkers. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2014, 23, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, W.; Tan, S.; Yamada, H.; Krishnamoorthy, T.; Chang, J.P.; Yeo, C.; Tan, C. Performance of the GALAD Model in an Asian Cohort Undergoing Hepatocellular Carcinoma Surveillance: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, 40, 1818–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schotten, C.; Ostertag, B.; Sowa, J.-P.; Manka, P.; Bechmann, L.P.; Hilgard, G.; Marquardt, C.; Wichert, M.; Toyoda, H.; Lange, C.M.; et al. GALAD Score Detects Early-Stage Hepatocellular Carcinoma in a European Cohort of Chronic Hepatitis B and C Patients. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, R.W.; Ong, C.E.Y.; Ong, E.Y.H.; Chung, C.H.; Lim, W.H.; Xiao, J.; Danpanichkul, P.; Law, J.H.; Syn, N.; Chee, D.; et al. Global Prevalence, Clinical Characteristics, Surveillance, Treatment Allocation, and Outcomes of Alcohol-Associated Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 22, 2394–2402.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, D.J.H.; Ng, C.H.; Lin, S.Y.; Pan, X.H.; Tay, P.; Lim, W.H.; Teng, M.; Syn, N.; Lim, G.; Yong, J.N.; et al. Clinical characteristics, surveillance, treatment allocation, and outcomes of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-related hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.J.; Li, M.; Vutien, P.; Mecham, B.; Borgerding, J.; Swarts, K.; Atuluru, P.; Michel, M.C.; Giustini, A.B.; Mezzacappa, C.; et al. Changes in Liver Disease Etiology Support a Lower Alpha-Fetoprotein Threshold for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Screening. Gastroenterology 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stine, J.G.; Wentworth, B.J.; Zimmet, A.; Rinella, M.E.; Loomba, R.; Caldwell, S.H.; Argo, C.K. Systematic review with meta-analysis: Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis without cirrhosis compared to other liver diseases. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 48, 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitellius, C.; Desjonqueres, E.; Lequoy, M.; Amaddeo, G.; Fouchard, I.; N’kOntchou, G.; Canivet, C.M.; Ziol, M.; Regnault, H.; Lannes, A.; et al. MASLD-related HCC: Multicenter study comparing patients with and without cirrhosis. JHEP Rep. 2024, 6, 101160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, S.; El-Serag, H.B.; Sada, Y.H.; Kanwal, F.; Duan, Z.; Temple, S.; May, S.B.; Kramer, J.R.; Richardson, P.A.; Davila, J.A. Hepatocellular Carcinoma in the Absence of Cirrhosis in United States Veterans Is Associated with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 14, 124–131.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Daher, D.; Yekkaluri, S.; Ng, M.; Rich, N.E.; Singal, A.G. Addition of AFP Improves Sensitivity of Ultrasound for Early-Stage HCC Detection in Patients with Cirrhosis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuck, M.K.; Chan, D.W.; Chia, D.; Godwin, A.K.; Grizzle, W.E.; Krueger, K.E.; Rom, W.; Sanda, M.; Sorbara, L.; Stass, S.; et al. Standard Operating Procedures for Serum and Plasma Collection: Early Detection Research Network Consensus Statement Standard Operating Procedure Integration Working Group. J. Proteome Res. 2009, 8, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-F.; Kroeniger, K.; Wang, C.-W.; Jang, T.-Y.; Yeh, M.-L.; Liang, P.-C.; Wei, Y.-J.; Hsu, P.-Y.; Huang, C.-I.; Hsieh, M.-Y.; et al. Surveillance Imaging and GAAD/GALAD Scores for Detection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients with Chronic Hepatitis. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2024, 12, 907–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fetzer, D.T.; Browning, T.; Xi, Y.; Yokoo, T.; Singal, A.G. Associations of Ultrasound LI-RADS Visualization Score with Examination, Sonographer, and Radiologist Factors: Retrospective Assessment in Over 10,000 Examinations. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2021, 218, 1010–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, T.A.; Maturen, K.E.; Dahiya, N.; Sun, M.R.M.; Kamaya, A.; American College of Radiology Ultrasound Liver Imaging; Reporting Data System (US LI-RADS) Working Group. US LI-RADS: Ultrasound liver imaging reporting and data system for screening and surveillance of hepatocellular carcinoma. Abdom. Imaging 2017, 43, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, P.; Soundararajan, R.; Patel, A.; Kumar-M, P.; Sharma, V.; Kalra, N. Abbreviated MRI for hepatocellular carcinoma screening: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Hepatol. 2021, 75, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Choi, S.H.; Shim, J.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, S.S.; Byun, J.H.; Choi, J.-I. Meta-Analysis of the Accuracy of Abbreviated Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Surveillance: Non-Contrast versus Hepatobiliary Phase-Abbreviated Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Cancers 2021, 13, 2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.K.; Lee, S.; Lee, M.Y.; Kim, M.-J. Effectiveness of noncontrast-abbreviated magnetic resonance imaging in a real-world hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance. Eur. Radiol. 2025, 35, 5792–5800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Kim, D.W.; Choi, W.-M.; Kim, S.Y. Abbreviated MRI-Based Surveillance Strategies for Early Hepatocellular Carcinoma Detection. J. Korean Soc. Radiol. 2025, 86, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.W.; Chang, W.; Kim, S.Y.; Lim, Y.-S.; Choi, J.; Cho, J.; Kim, J.-W.; Cho, J.Y.; Jeon, S.K.; Bin Lee, Y.; et al. Non-contrast magnetic resonance imaging for detection of late recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after curative treatment: A prospective multicenter comparison to contrast-enhanced computed tomography. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2025, 31, 1285–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singal, A.G.; Tiro, J.A.; Murphy, C.C.; Blackwell, J.-M.; Kramer, J.R.; Khan, A.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Phillips, J.L.; Hernaez, R. Patient-Reported Barriers Are Associated with Receipt of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Surveillance in a Multicenter Cohort of Patients with Cirrhosis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 19, 987–995.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, S.-Y.Z.; Sangha, K.; Fujiwara, N.; Hoshida, Y.; Parikh, N.D.; Singal, A.G. Cost-effectiveness of a precision hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance strategy in patients with cirrhosis. eClinicalMedicine 2024, 75, 102755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singal, A.G.; Chhatwal, J.; Parikh, N.; Tapper, E. Cost-Effectiveness of a Biomarker-Based Screening Strategy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients with Cirrhosis. Liver Cancer 2024, 13, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeoui, T.; Kositamongkol, C.; Chantrakul, R.; Sripongpun, P.; Chamroonkul, N.; Kongkamol, C.; Phisalprapa, P.; Kaewdech, A. Cost-Utility Analysis of Biomarker-Based vs. USG + AFP Strategies for HCC Surveillance in Chronic Hepatitis B. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singal, A.G.; Parikh, N.D.; Kanwal, F.; Marrero, J.A.; Deodhar, S.; Page-Lester, S.; Lopez, C.; Feng, Z.; Tayob, N. National Liver Cancer Screening Trial (TRACER) study protocol. Hepatol. Commun. 2024, 8, e0565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoenberger, H.; Chong, N.; Fetzer, D.T.; Rich, N.E.; Yokoo, T.; Khatri, G.; Olivares, J.; Parikh, N.D.; Yopp, A.C.; Marrero, J.A.; et al. Dynamic Changes in Ultrasound Quality for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Screening in Patients with Cirrhosis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 20, 1561–1569.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beudeker, B.J.; Fu, S.; Balderramo, D.; Mattos, A.Z.; Carrera, E.; Diaz, J.; Prieto, J.; Banales, J.; Vogel, A.; Arrese, M.; et al. Validation and optimization of AFP-based biomarker panels for early HCC detection in Latin America and Europe. Hepatol. Commun. 2023, 7, e0264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singal, A.G.; Yang, J.D.; Jalal, P.K.; Salgia, R.; Mehta, N.; Hoteit, M.A.; Kao, K.; Daher, D.; El Dahan, K.S.; Hernandez, P.; et al. Patient-Perceived Risk of Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Net Benefit of Surveillance: A Multicenter Survey Study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2025, 120, 1800–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolen, S.A.; Singal, A.G.; Davenport, M.S.; Troost, J.P.; Khalatbari, S.; Mittal, S.; Siddiqui, S.; Fobar, A.; Morris, J.; Odewole, M.; et al. Patient Preferences for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Surveillance Parameters. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 20, 204–215.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singal, A.G.; Quirk, L.; Boike, J.; Chernyak, V.; Feng, Z.; Giamarqo, G.; Kanwal, F.; Ioannou, G.N.; Manes, S.; Marrero, J.A.; et al. Value of HCC surveillance in a landscape of emerging surveillance options: Perspectives of a multi-stakeholder modified Delphi panel. Hepatology 2024, 82, 794–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, T.L.; Parikh, N.D.; Roberts, L.R.; Schwartz, M.E.; Nguyen, M.H.; Befeler, A.; Page-Lester, S.; Tayob, N.; Srivastava, S.; Rinaudo, J.A.; et al. A Phase 3 Biomarker Validation of GALAD for the Detection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2024, 168, 316–326.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderaro, J.; Seraphin, T.P.; Luedde, T.; Simon, T.G. Artificial intelligence for the prevention and clinical management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2022, 76, 1348–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audureau, E.; Carrat, F.; Layese, R.; Cagnot, C.; Asselah, T.; Guyader, D.; Larrey, D.; De Lédinghen, V.; Ouzan, D.; Zoulim, F.; et al. Personalized surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis—Using machine learning adapted to HCV status. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 1434–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Hur, M.H.; Song, B.G.; Park, S.Y.; Kim, G.-A.; Choi, G.; Nam, J.Y.; Kim, M.A.; Park, Y.; Ko, Y.; et al. AI model using CT-based imaging biomarkers to predict hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis B. J. Hepatol. 2024, 82, 1080–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Hao, X.; Chen, L.; Qian, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, X.; Fan, X.; Jiang, G.; Zheng, D.; Gao, P.; et al. Early warning of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients by three-phase CT-based deep learning radiomics model: A retrospective, multicentre, cohort study. eClinicalMedicine 2024, 74, 102718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalasani, N.P.; Ramasubramanian, T.S.; Bhattacharya, A.; Olson, M.C.; V, D.K.E.; Roberts, L.R.; Kisiel, J.B.; Reddy, K.R.; Lidgard, G.P.; Johnson, S.C.; et al. A Novel Blood-Based Panel of Methylated DNA and Protein Markers for Detection of Early-Stage Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 19, 2597–2605.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.; Lin, Y.; Xu, J.; Liu, D.; Li, D.; Meng, H.; Gallant, M.A.; Kubota, N.; Roy, D.; Li, J.S.; et al. A multi-analyte cell-free DNA–based blood test for early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol. Commun. 2022, 6, 1753–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Huang, A.; Sun, J.; Zhang, S.; Cheng, J.; Jiang, R.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhang, F.; Peng, J.; et al. The genomic and epigenomic abnormalities of plasma cfDNA as liquid biopsy biomarkers to detect hepatocellular carcinoma: A multicenter cohort study. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2025, 18, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Xu, J.; Li, D.; Zhang, X.; Chen, D.; Xie, F.; Huang, L.; Yu, X.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, Y. HepaClear, a blood-based panel combining novel methylated CpG sites and protein markers, for the detection of early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin. Epigenetics 2023, 15, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, B.; Yang, K.; Wang, Z.; Li, Q.; Wang, W.; Chen, D.; Ma, J.; Zhou, J. Development of a circulating tumor DNA methylation biomarker panel for hepatocellular carcinoma detection. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. (EJSO) 2025, 52, 111167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, B.; Ma, F.; Liu, H.; Hu, J.; Rao, L.; Liu, C.; Jiang, Y.; Kuangzeng, S.; Lin, X.; Wang, C.; et al. Cell-free DNA methylation markers for differential diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Med. 2022, 20, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kisiel, J.B.; Dukek, B.A.; Kanipakam, R.V.S.R.; Ghoz, H.M.; Yab, T.C.; Berger, C.K.; Taylor, W.R.; Foote, P.H.; Giama, N.H.; Onyirioha, K.; et al. Hepatocellular Carcinoma Detection by Plasma Methylated DNA: Discovery, Phase I Pilot, and Phase II Clinical Validation. Hepatology 2019, 69, 1180–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardet, R.; Dubois, M.; Manasseh, G.; Jreige, M.; Du Pasquier, C.; Canniff, E.; Gulizia, M.; Bonvin, M.; Aleman, Y.; Taouli, B.; et al. The combination of non-contrast abbreviated MRI and alpha foetoprotein has high performance for hepatocellular carcinoma screening. Eur. Radiol. 2023, 33, 6929–6938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.L.Y.; Hu, Y.; Malinowsky, K.; Madin, K.; Kroeniger, K.; Hou, J.; Sharma, A. Prospective appraisal of clinical diagnostic algorithms for hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B infection. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demirtas, C.O.; Akin, S.; Karadag, D.Y.; Yilmaz, T.; Ciftci, U.; Huseynov, J.; Bulte, T.T.; Kaldirim, Y.A.; Dilber, F.; Ozdogan, O.C.; et al. Enhancing Hepatocellular Carcinoma Surveillance: Comparative Evaluation of AFP, AFP-L3, DCP and Composite Models in a Biobank-Based Case-Control Study. Cancers 2025, 17, 2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| HCC Cases (n = 71) | Cirrhosis Controls (n = 81) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <0.001 | ||

| <65 | 36 (50.7%) | 70 (86.4%) | |

| ≥65 | 35 (49.3%) | 11 (13.6%) | |

| Sex | 0.07 | ||

| Women | 25 (35.2%) | 41 (50.6%) | |

| Men | 46 (64.8%) | 40 (49.4%) | |

| Race and Ethnicity | 0.32 | ||

| Hispanic White | 37 (52.1%) | 39 (48.1%) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 28 (39.4%) | 36 (44.4%) | |

| Black | 4 (5.6%) | 1 (1.2%) | |

| Asian | 2 (2.8%) | 5 (6.2%) | |

| Liver disease Etiology | 0.87 | ||

| ALD | 33 (46.5%) | 39 (48.1%) | |

| MASLD | 38 (53.5%) | 42 (51.9%) | |

| Child-Pugh Class | 0.01 | ||

| A | 31 (43.7%) | 50 (64.9%) | |

| B/C | 40 (56.3%) | 27 (35.1%) | |

| Body mass index category | 0.68 | ||

| Normal | 10 (14.1%) | 14 (17.3%) | |

| Overweight | 24 (33.8%) | 22 (27.2%) | |

| Obesity class I | 20 (28.2%) | 19 (23.5%) | |

| Obesity class II | 9 (12.7%) | 16 (19.8%) | |

| Obesity class III | 8 (11.3%) | 10 (12.3%) | |

| Number of HCC tumors, median (IQR) | 1 (1–2) | - | - |

| Maximum tumor diameter (cm), median (IQR) | 3.9 (2.6–6.8) | - | - |

| BCLC staging | - | - | |

| Stage 0 | 3 (4.2%) | ||

| Stage A | 36 (50.7%) | ||

| Stage B | 7 (9.9%) | ||

| Stage C | 17 (23.9%) | ||

| Stage D | 8 (11.3%) |

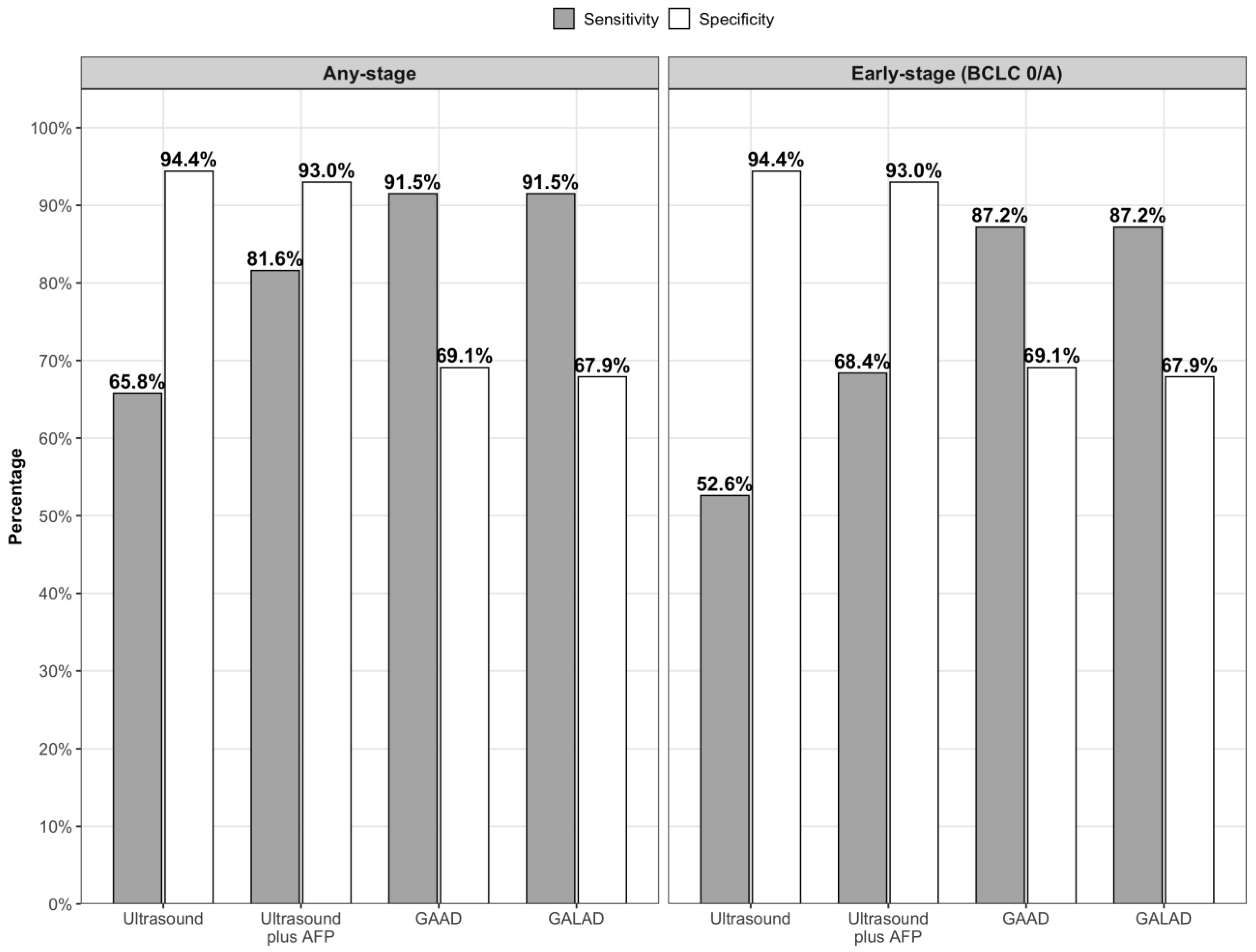

| Test | AUROC | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any-stage HCC (n = 71 cases, 81 controls) | |||

| Ultrasound (n = 109) | 0.80 (95% CI 0.72–0.88) | 65.8% (95% CI 48.6–80.4%) | 94.4% (95% CI 86.2–98.4%) |

| Ultrasound plus AFP (n = 109) | 0.88 (95% CI 0.80–0.96) | 81.6% (95% CI 65.7–92.3%) | 93.0% (95% CI 84.3–97.7%) |

| GAAD (n = 152) | 0.92 (95% CI 0.88–0.97) | 91.5% (95% CI 82.5–96.8%) | 69.1% (95% CI 57.9–78.9%) |

| GALAD (n = 152) | 0.92 (95% CI 0.88–0.97) | 91.5% (95% CI 82.5–96.8%) | 67.9% (95% CI 56.6–77.8%) |

| Early-stage HCC (n = 39 cases, 81 controls) | |||

| Ultrasound (n = 90) | 0.73 (95% CI 0.62–0.85) | 52.6% (95% CI 28.9–75.6%) | 94.4% (95% CI 86.2–98.4%) |

| Ultrasound plus AFP (n = 90) | 0.79 (95% CI 0.64–0.93) | 68.4% (95% CI 43.4–87.4%) | 93.0% (95% CI 84.3–97.7%) |

| GAAD (n = 120) | 0.90 (95% CI 0.84–0.96) | 87.2% (95% CI 72.6–95.7%) | 69.1% (95% CI 57.9–78.9%) |

| GALAD (n = 120) | 0.90 (95% CI 0.84–0.96) | 87.2% (95% CI 72.6–95.7%) | 67.9% (95% CI 56.6–77.8%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jarrah, M.; Deodhar, S.; Quirk, L.; Al-Hasan, M.; Sharma, A.; Bhamra, G.; Terrell, J.; Kanwal, F.; Hoshida, Y.; Rich, N.E.; et al. Performance of GAAD and GALAD Biomarker Panels for HCC Detection in Patients with MASLD or ALD Cirrhosis. Cancers 2025, 17, 3835. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233835

Jarrah M, Deodhar S, Quirk L, Al-Hasan M, Sharma A, Bhamra G, Terrell J, Kanwal F, Hoshida Y, Rich NE, et al. Performance of GAAD and GALAD Biomarker Panels for HCC Detection in Patients with MASLD or ALD Cirrhosis. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3835. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233835

Chicago/Turabian StyleJarrah, Mohammad, Sneha Deodhar, Lisa Quirk, Mohammed Al-Hasan, Ashish Sharma, Guruveer Bhamra, Julia Terrell, Fasiha Kanwal, Yujin Hoshida, Nicole E. Rich, and et al. 2025. "Performance of GAAD and GALAD Biomarker Panels for HCC Detection in Patients with MASLD or ALD Cirrhosis" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3835. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233835

APA StyleJarrah, M., Deodhar, S., Quirk, L., Al-Hasan, M., Sharma, A., Bhamra, G., Terrell, J., Kanwal, F., Hoshida, Y., Rich, N. E., Gopal, P., & Singal, A. G. (2025). Performance of GAAD and GALAD Biomarker Panels for HCC Detection in Patients with MASLD or ALD Cirrhosis. Cancers, 17(23), 3835. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233835