Survival Determinants and Treatment Outcomes of Patients with Small Cell Lung Cancer and Brain Metastases: A U.S. National Analysis †

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

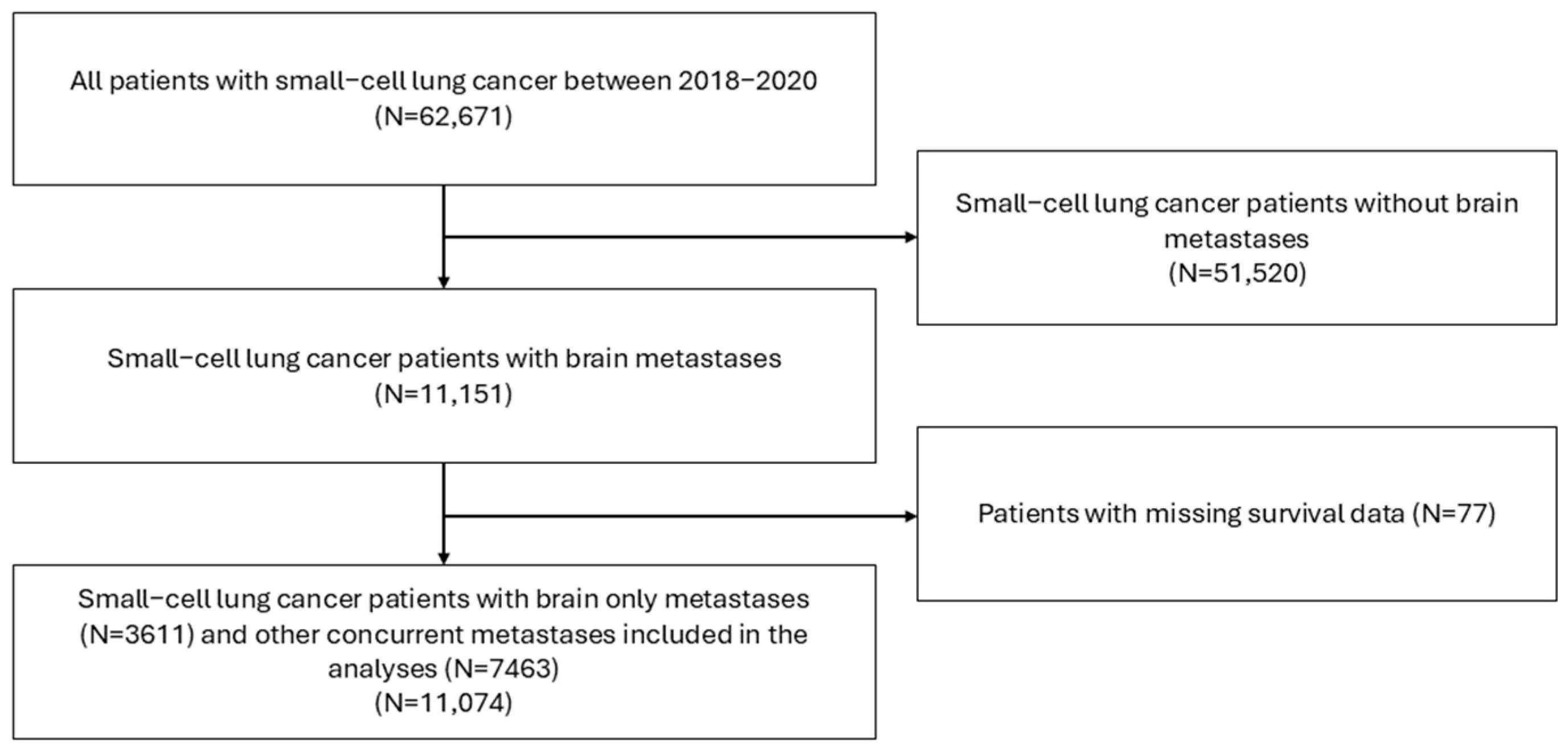

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Study Design

2.2. Variables and Definitions

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

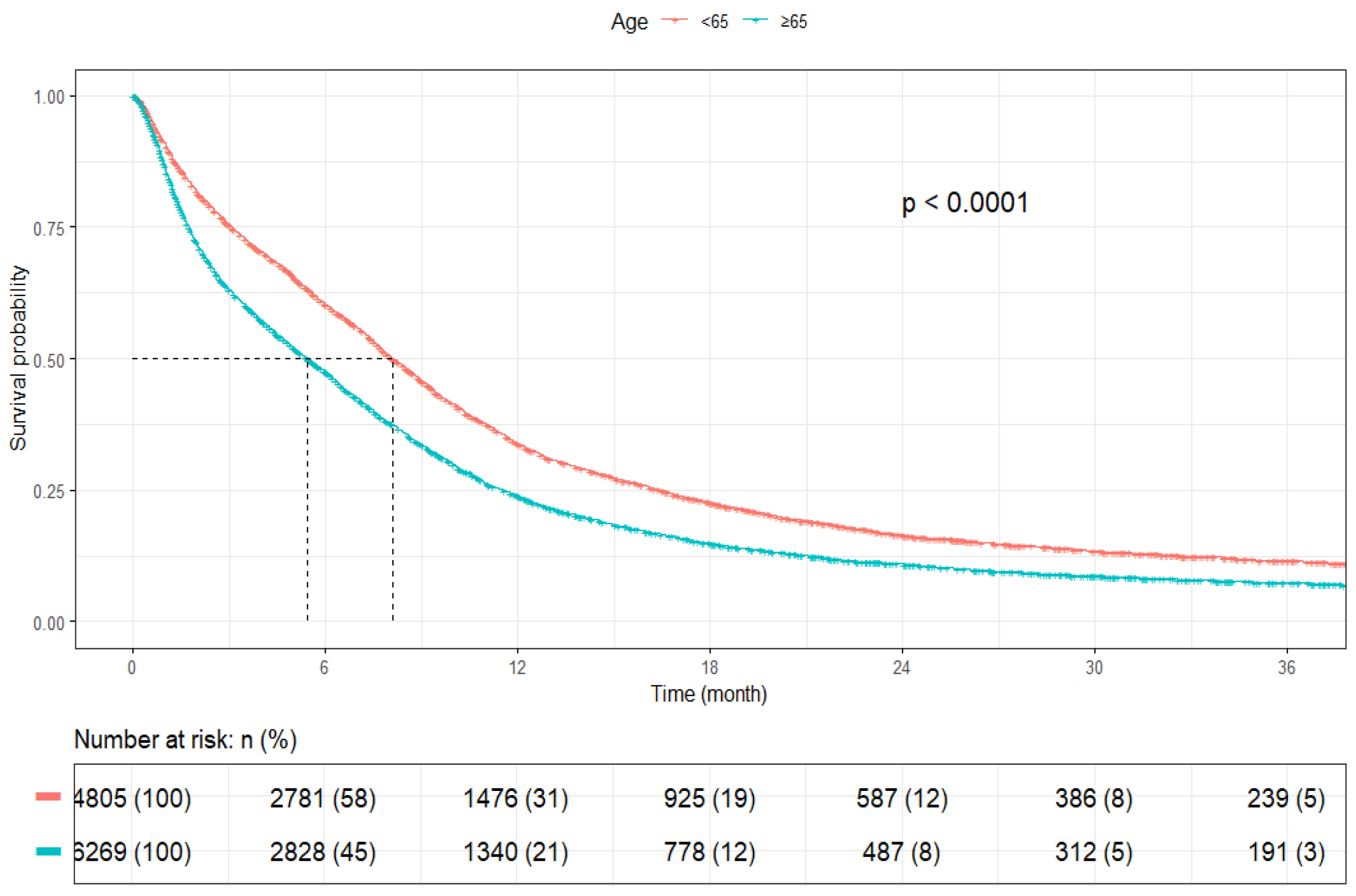

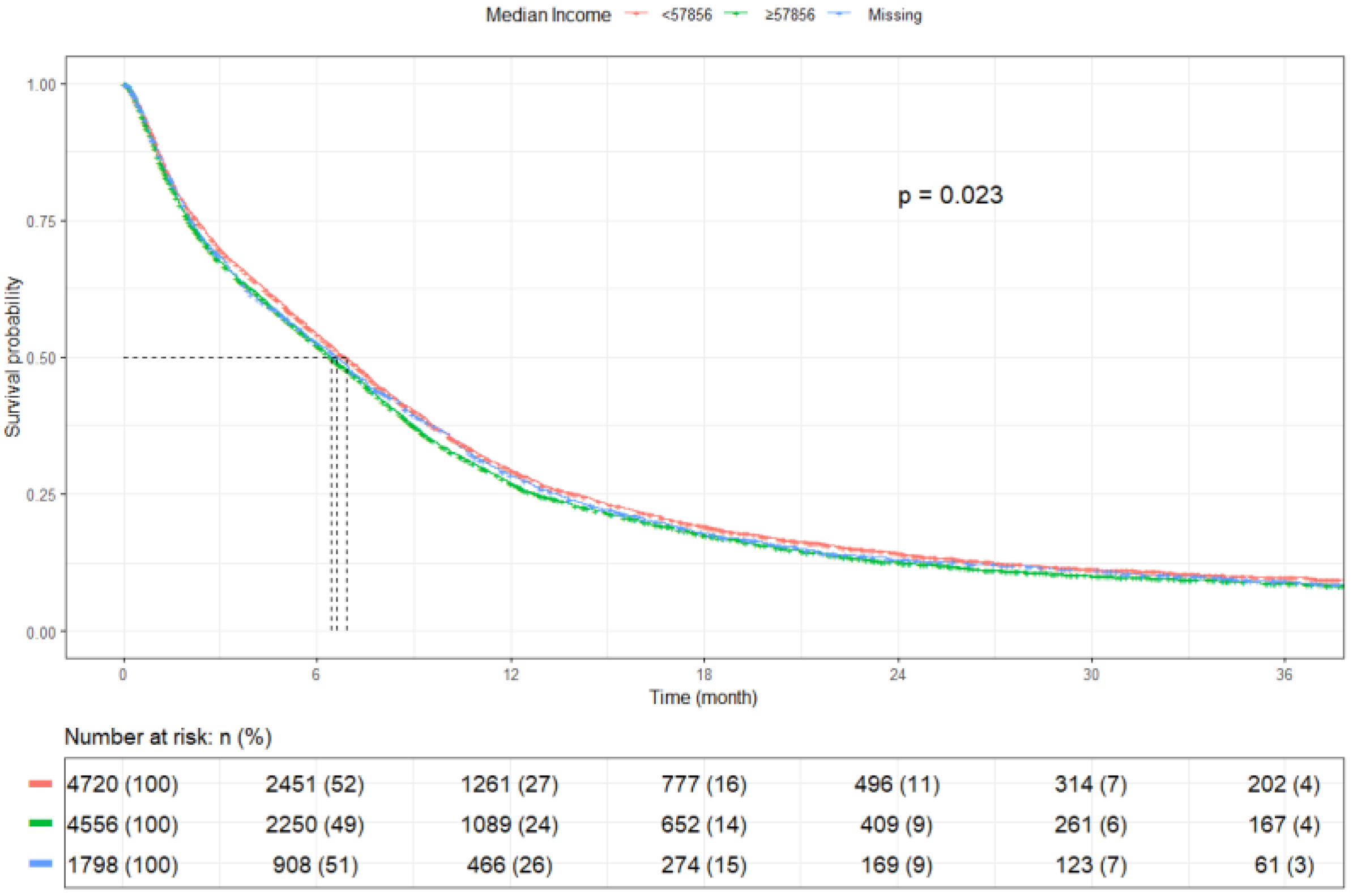

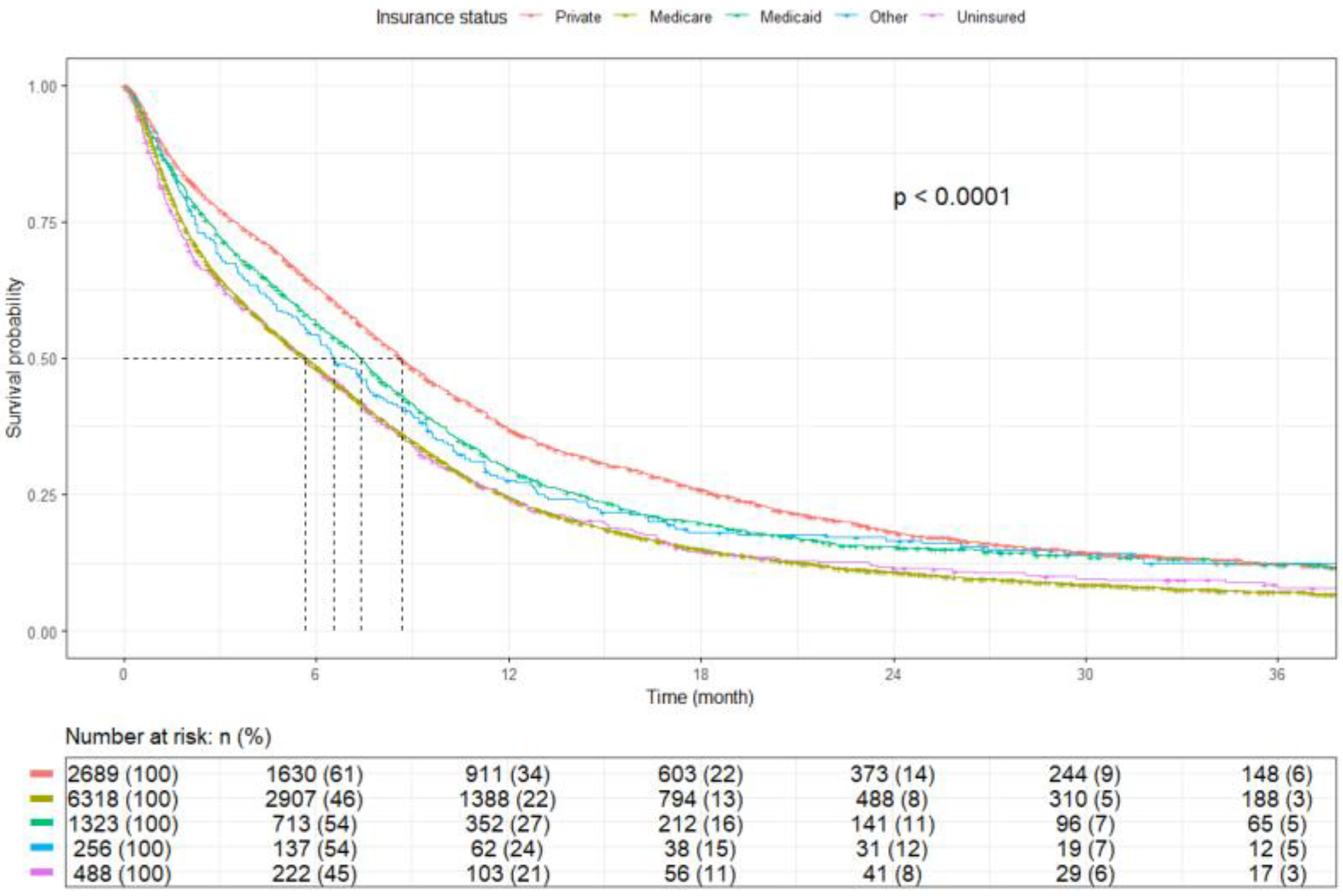

3.2. Survival Outcomes

3.3. Factors Associated with Overall Survival (Multivariable Analysis)

3.4. Subgroup Analyses by Extent of Metastatic Disease

3.5. Assessment of Proportional Hazards and AFT Model Validation

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BM | Brain metastases |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| mOS | Median overall survival |

| NCDB | National Cancer Database |

| OS | Overall survival |

| PCI | Prophylactic cranial irradiation |

| SCLC | Small cell lung cancer |

| SRS | Stereotactic radiosurgery |

| Sys | Systemic therapy |

| WBRT | Whole-brain radiotherapy |

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Kratzer, T.B.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2025, 75, 10–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Cancer. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Cancer Stat Facts: Lung and Bronchus Cancer. Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/lungb.html (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Wang, Q.; Gümüş, Z.H.; Colarossi, C.; Memeo, L.; Wang, X.; Kong, C.Y.; Boffetta, P. SCLC: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Genetic Susceptibility, Molecular Pathology, Screening, and Early Detection. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2023, 18, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, R.; Page, N.; Morgensztern, D.; Read, W.; Tierney, R.; Vlahiotis, A.; Spitznagel, E.L.; Piccirillo, J. Changing epidemiology of small-cell lung cancer in the United States over the last 30 years: Analysis of the surveillance, epidemiologic, and end results database. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 4539–4544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Paz-Ares, L.; Reinmuth, N.; Garassino, M.C.; Statsenko, G.; Hochmair, M.J.; Özgüroğlu, M.; Verderame, F.; Havel, L.; Losonczy, G.; et al. Impact of Brain Metastases on Treatment Patterns and Outcomes with First-Line Durvalumab Plus Platinum-Etoposide in Extensive-Stage SCLC (CASPIAN): A Brief Report. JTO Clin. Res. Rep. 2022, 3, 100330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Schalper, K.A.; Chiang, A. Mechanisms of immunotherapy resistance in small cell lung cancer. Cancer Drug Resist. 2024, 7, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.L.; Lu, S.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, B.; Hu, C.; Lin, L.; Zhong, W. Expert consensus on treatment for stage III non-small cell lung cancer. Med. Adv. 2023, 1, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudin, C.M.; Brambilla, E.; Faivre-Finn, C.; Sage, J. Small-cell lung cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2021, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukas, R.V.; Gondi, V.; Kamson, D.O.; Kumthekar, P.; Salgia, R. State-of-the-art considerations in small cell lung cancer brain metastases. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 71223–71233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, T.; Takahashi, N.; Chakraborty, S.; Takebe, N.; Nassar, A.H.; Karim, N.A.; Puri, S.; Naqash, A.R. Emerging advances in defining the molecular and therapeutic landscape of small-cell lung cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 21, 610–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, V.; Zhang, B.; Tang, M.; Peng, W.; Amos, C.; Cheng, C. Racial and socioeconomic disparities in survival improvement of eight cancers. BJC Rep. 2024, 2, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redondo-Sánchez, D.; Petrova, D.; Rodríguez-Barranco, M.; Fernández-Navarro, P.; Jiménez-Moleón, J.J.; Sánchez, M.J. Socio-Economic Inequalities in Lung Cancer Outcomes: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. Cancers 2022, 14, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tannenbaum, S.L.; Koru-Sengul, T.; Zhao, W.; Miao, F.; Byrne, M.M. Survival disparities in non-small cell lung cancer by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. Cancer J. 2014, 20, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.; Li, G.; Bhambhvani, H.; Hayden-Gephart, M. Socioeconomic Disparities in Brain Metastasis Survival and Treatment: A Population-Based Study. World Neurosurg. 2022, 158, e636–e644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, T.; Walker, P.; Podder, T.; Efird, J.T. Effect of Race and Insurance on the Outcome of Stage I Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Anticancer. Res. 2015, 35, 4243–4249. [Google Scholar]

- Said, R.; Terjanian, T.; Taioli, E. Clinical characteristics and presentation of lung cancer according to race and place of birth. Future Oncol. 2010, 6, 1353–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Shi, H.; Chen, R.; Cochuyt, J.J.; Hodge, D.O.; Manochakian, R.; Zhao, Y.; Ailawadhi, S.; Lou, Y. Association of Race, Socioeconomic Factors, and Treatment Characteristics with Overall Survival in Patients with Limited-Stage Small Cell Lung Cancer. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2032276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, S.H.; Ziogas, A.; Zell, J.A. Prognostic factors for survival in extensive stage small cell lung cancer (ED-SCLC): The importance of smoking history, socioeconomic and marital statuses, and ethnicity. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2009, 4, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffa, D.J.; Rosen, J.E.; Mallin, K.; Loomis, A.; Gay, G.; Palis, B.; Thoburn, K.; Gress, D.; McKellar, D.P.; Shulman, L.N.; et al. Using the National Cancer Database for Outcomes Research: A Review. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 1722–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NAACR. North American Association of Central Cancer Registries, Inc. (NAACCR) 2018 Implementation Guidelines and Recommendations. Available online: https://www.naaccr.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/2018-Implementation-Guidelines20181101a.pdf? (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Post, A. FDA Approves Atezolizumab for Extensive-Stage Small Cell Lung Cancer. Available online: https://ascopost.com/News/59852 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Bellur, S.S.; Jayram, D.; Ahmad, S.; Bhat, V.; Ozair, A.; Ganiyani, M.A.; Khosla, A.A.; Podder, V.; Ahluwalia, M.S. Socioeconomic disparities in survival outcomes of patients with SCLC with brain metastases: A nationwide analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, e20133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maryland Department of Planning SDAC. 2016–2020 Multi-Year ACS 5-Year Estimates for All Geographies. Available online: https://planning.maryland.gov/MSDC/Pages/american_community_survey/2016-2020ACS.aspx#:~:text=The%202016-2020%205-year%20American%20Community%20Survey%20%28ACS%29%20estimates,Acrobat%20file%20%28social%2C%20economic%2C%20housing%2C%20and%20demographic%20profiles%29 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Ludbrook, J.J.; Truong, P.T.; MacNeil, M.V.; Lesperance, M.; Webber, A.; Joe, H.; Martins, H.; Lim, J. Do age and comorbidity impact treatment allocation and outcomes in limited stage small-cell lung cancer? a community-based population analysis. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2003, 55, 1321–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Shi, F.; Zhang, C.; Jiao, Q.; Zhu, H. Better cancer specific survival in young small cell lung cancer patients especially with AJCC stage III. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 34923–34934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roof, L.; Wei, W.; Tullio, K.; Pennell, N.A.; Stevenson, J.P. Impact of Socioeconomic Factors on Overall Survival in SCLC. JTO Clin. Res. Rep. 2022, 3, 100360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Tang, J.; Sun, T.; Zheng, X.; Li, J.; Sun, H.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, Z.; et al. Survival changes in patients with small cell lung cancer and disparities between different sexes, socioeconomic statuses and ages. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albain, K.S.; Crowley, J.J.; LeBlanc, M.; Livingston, R.B. Determinants of improved outcome in small-cell lung cancer: An analysis of the 2,580-patient Southwest Oncology Group data base. J. Clin. Oncol. 1990, 8, 1563–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uprety, D.; Seaton, R.; Hadid, T.; Mamdani, H.; Sukari, A.; Ruterbusch, J.J.; Schwartz, A.G. Racial and socioeconomic disparities in survival among patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2024, 116, 1697–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, D.N.; Sandler, K.L.; Henderson, L.M.; Rivera, M.P.; Aldrich, M.C. Disparities in Lung Cancer Screening: A Review. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2020, 17, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackstock, A.W.; Herndon, J.E., 2nd; Paskett, E.D.; Miller, A.A.; Lathan, C.; Niell, H.B.; Socinski, M.A.; Vokes, E.E.; Green, M.R. Similar outcomes between African American and non-African American patients with extensive-stage small-cell lung carcinoma: Report from the Cancer and Leukemia Group B. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, S., 3rd; Page, B.R.; Jaboin, J.J.; Chapman, C.H.; Deville, C., Jr.; Thomas, C.R., Jr. The pervasive crisis of diminishing radiation therapy access for vulnerable populations in the United States, part 1: African-American patients. Adv. Radiat. Oncol. 2017, 2, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascha, M.S.; Funk, K.; Sloan, A.E.; Kruchko, C.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. Disparities in the use of stereotactic radiosurgery for the treatment of lung cancer brain metastases: A SEER-Medicare study. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2020, 37, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, E.F.; Ten Haaf, K.; Arenberg, D.A.; de Koning, H.J. Disparities in Receiving Guideline-Concordant Treatment for Lung Cancer in the United States. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2020, 17, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noda, K.; Nishiwaki, Y.; Kawahara, M.; Negoro, S.; Sugiura, T.; Yokoyama, A.; Fukuoka, M.; Mori, K.; Watanabe, K.; Tamura, T.; et al. Irinotecan plus cisplatin compared with etoposide plus cisplatin for extensive small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, N.; Bunn, P.A., Jr.; Langer, C.; Einhorn, L.; Guthrie, T., Jr.; Beck, T.; Ansari, R.; Ellis, P.; Byrne, M.; Morrison, M.; et al. Randomized phase III trial comparing irinotecan/cisplatin with etoposide/cisplatin in patients with previously untreated extensive-stage disease small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 2038–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klugman, M.; Xue, X.; Hosgood, H.D., 3rd. Race/ethnicity and lung cancer survival in the United States: A meta-analysis. Cancer Causes Control 2019, 30, 1231–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapan, U.; Furtado, V.F.; Qureshi, M.M.; Everett, P.; Suzuki, K.; Mak, K.S. Racial and Other Healthcare Disparities in Patients with Extensive-Stage SCLC. JTO Clin. Res. Rep. 2021, 2, 100109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, R.; Pillai, R.N.; Owonikoko, T.K.; Steuer, C.E.; Saba, N.F.; Pakkala, S.; Patel, P.R.; Belani, C.P.; et al. Survival Outcomes with Thoracic Radiotherapy in Extensive-Stage Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis of the National Cancer Database. Clin. Lung Cancer 2019, 20, 484–493.e486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLean, M.; Luo, X.; Wang, S.; Kernstine, K.; Gerber, D.E.; Xie, Y. Outcomes of neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy in stage 2 and 3 non-small cell lung cancer: An analysis of the National Cancer Database. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 24470–24479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, F.B.; Morris, C.R.; Parikh-Patel, A.; Cress, R.D.; Keegan, T.H.M.; Li, C.S.; Lin, P.S.; Kizer, K.W. Disparities in Systemic Treatment Use in Advanced-stage Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer by Source of Health Insurance. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2019, 28, 1059–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groth, S.S.; Al-Refaie, W.B.; Zhong, W.; Vickers, S.M.; Maddaus, M.A.; D’Cunha, J.; Habermann, E.B. Effect of insurance status on the surgical treatment of early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2013, 95, 1221–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y.; Dholaria, B.; Soyano, A.; Hodge, D.; Cochuyt, J.; Manochakian, R.; Ko, S.J.; Thomas, M.; Johnson, M.M.; Patel, N.M.; et al. Survival trends among non-small-cell lung cancer patients over a decade: Impact of initial therapy at academic centers. Cancer Med. 2018, 7, 4932–4942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusthoven, C.G.; Yamamoto, M.; Bernhardt, D.; Smith, D.E.; Gao, D.; Serizawa, T.; Yomo, S.; Aiyama, H.; Higuchi, Y.; Shuto, T.; et al. Evaluation of First-line Radiosurgery vs Whole-Brain Radiotherapy for Small Cell Lung Cancer Brain Metastases: The FIRE-SCLC Cohort Study. JAMA Oncol. 2020, 6, 1028–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robin, T.P.; Jones, B.L.; Amini, A.; Koshy, M.; Gaspar, L.E.; Liu, A.K.; Nath, S.K.; Kavanagh, B.D.; Camidge, D.R.; Rusthoven, C.G. Radiosurgery alone is associated with favorable outcomes for brain metastases from small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2018, 120, 88–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, W.; Haque, W.; Verma, V.; Butler, B.; Teh, B.S. Stereotactic radiosurgery for brain metastases from newly diagnosed small cell lung cancer: Practice patterns and outcomes. Acta Oncol. 2019, 58, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Level | All (N = 11,074) | SCLC with BM Only (N = 3611) | SCLC-BM with Other Concurrent Metastases (N = 7463) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Median (IQR) | 66.0 (60.0 to 73.0) | 66.0 (60.0 to 73.0) | 66.0 (60.0 to 72.0) |

| <65 years | 4805 (43.4) | 1513 (41.9) | 3292 (44.1) | |

| ≥65 years | 6269 (56.6) | 2098 (58.1) | 4171 (55.9) | |

| Sex | Male | 5591 (50.5) | 1697 (47.0) | 3894 (52.2) |

| Female | 5483 (49.5) | 1914 (53.0) | 3569 (47.8) | |

| Race | White | 9727 (87.8) | 3089 (85.5) | 6638 (88.9) |

| Black | 1005 (9.1) | 398 (11.0) | 607 (8.1) | |

| Asian | 147 (1.3) | 54 (1.5) | 93 (1.2) | |

| Other | 195 (1.8) | 70 (1.9) | 125 (1.7) | |

| Ethnicity | Non-Hispanic | 10,591 (95.6) | 3441 (95.3) | 7150 (95.8) |

| Hispanic | 483 (4.4) | 170 (4.7) | 313 (4.2) | |

| Charlson–Deyo Comorbidity Index | 0 | 6354 (57.4) | 2064 (57.2) | 4290 (57.5) |

| 1 | 2659 (24.0) | 868 (24.0) | 1791 (24.0) | |

| 2–3 | 2061 (18.6) | 679 (18.8) | 1382 (18.5) | |

| Insurance | Private | 2689 (24.3) | 830 (23.0) | 1859 (24.9) |

| Medicare | 6318 (57.1) | 2085 (57.7) | 4233 (56.7) | |

| Medicaid | 1323 (11.9) | 450 (12.5) | 873 (11.7) | |

| Other | 256 (2.3) | 80 (2.2) | 176 (2.4) | |

| Uninsured | 488 (4.4) | 166 (4.6) | 322 (4.3) | |

| Median Income * | ≥$57,856 | 4720 (42.6) | 1512 (41.9) | 3208 (43.0) |

| <$57,856 | 4556 (41.1) | 1528 (42.3) | 3028 (40.6) | |

| Unknown | 1798 (16.2) | 571 (15.8) | 1227 (16.4) | |

| Education ** | ≥9.1% | 5291 (47.8) | 1806 (50.0) | 3485 (46.7) |

| <9.1% | 4013 (36.2) | 1245 (34.5) | 2768 (37.1) | |

| Unknown | 1770 (16.0) | 560 (15.5) | 1210 (16.2) | |

| Facility type | Academic | 3357 (30.3) | 1145 (31.7) | 2212 (29.6) |

| Integrated network | 2300 (20.8) | 732 (20.3) | 1568 (21.0) | |

| Community | 5384 (48.6) | 1725 (47.8) | 3659 (49.0) | |

| Unknown | 33 (0.3) | 9 (0.2) | 24 (0.3) | |

| Distance (Crowfly) *** | 11.2+ miles | 4713 (42.6) | 1585 (43.9) | 3128 (41.9) |

| <11.2 miles | 4666 (42.1) | 1486 (41.2) | 3180 (42.6) | |

| Missing | 1695 (15.3) | 540 (15.0) | 1155 (15.5) | |

| Year of diagnosis | 2018 | 3825 (34.5) | 1270 (35.2) | 2555 (34.2) |

| 2019 | 3827 (34.6) | 1242 (34.4) | 2585 (34.6) | |

| 2020 | 3422 (30.9) | 1099 (30.4) | 2323 (31.1) | |

| Treatment | SRS+Sys | 714 (6.4) | 298 (8.3) | 416 (5.6) |

| WBRT+Sys | 4488 (40.5) | 1469 (40.7) | 3019 (40.5) | |

| Sys | 2804 (25.3) | 696 (19.3) | 2108 (28.2) | |

| SRS | 127 (1.1) | 76 (2.1) | 51 (0.7) | |

| WBRT | 1073 (9.7) | 453 (12.5) | 620 (8.3) | |

| None | 1868 (16.9) | 619 (17.1) | 1249 (16.7) | |

| Vital status | Alive | 1678 (15.2) | 777 (21.5) | 901 (12.1) |

| Dead | 9396 (84.8) | 2834 (78.5) | 6562 (87.9) | |

| Median follow-up | Median (IQR) | 34.2 (24.6 to 44.4) | 34.7 (25.1 to 44.6) | 33.7 (24.3 to 44.3) |

| Cohort | Median (Months) | 3-month Survival Rate (%) | 6-month Survival Rate (%) | 1-year Survival Rate (%) | 2-year Survival Rate (%) | 3-year Survival Rate (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients (N = 11,074) | 6.60 (6.47–6.87) | 68.6 (67.7–69.4) | 53.1 (52.2–54.1) | 28.2 (27.4–29.1) | 13.4 (12.7–14.1) | 9.2 (8.6–9.8) | <0.0001 |

| SCLC with BM only (N = 3611) | 8.80 (8.38–9.26) | 73.6 (72.2–75.1) | 60.0 (58.4–61.6) | 39.0 (37.4–40.7) | 21.3 (19.9–22.7) | 15.4 (14.1–16.9) | |

| SCLC BM with other Concurrent metastases (N = 7463) | 5.95 (5.75–6.18) | 66.1 (65.1–67.2) | 49.8 (48.7–51.0) | 23.0 (22.0–24.0) | 9.5 (8.8–10.2) | 6.1 (5.5–6.8) |

| Cohort | Level | Number | Median OS (95%CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | All patients | 11,074 | 6.6 (6.5–6.9) | - |

| Age | <65 years | 4805 | 8.1 (7.8–8.5) | <0.0001 |

| ≥65 years | 6269 | 5.4 (5.2–5.7) | ||

| Gender | Male | 5591 | 6.1 (5.8–6.3) | <0.0001 |

| Female | 5483 | 7.3 (7.0–7.6) | ||

| Race | White | 9727 | 6.5 (6.3–6.7) | <0.0001 |

| Black | 1005 | 7.5 (6.8–8.2) | ||

| Asian | 147 | 8.3 (6.8–9.9) | ||

| Other | 195 | 7.6 (5.7–9.6) | ||

| Ethnicity | Non-Hispanic | 10,591 | 6.6 (6.4–6.8) | 0.011 |

| Hispanic | 483 | 7.5 (6.5–8.5) | ||

| Charlson–Deyo Comorbidity Index | 0 | 6354 | 7.4 (7.2–7.7) | <0.0001 |

| 1 | 2659 | 6.3 (6.0–6.6) | ||

| 2–3 | 2061 | 4.9 (4.5–5.3) | ||

| Median Income * | ≥$57,856 | 4720 | 6.9 (6.6–7.2) | 0.023 |

| <$57,856 | 4556 | 6.4 (6.2–6.7) | ||

| Unknown | 1798 | 6.6 (6.1–7.0) | ||

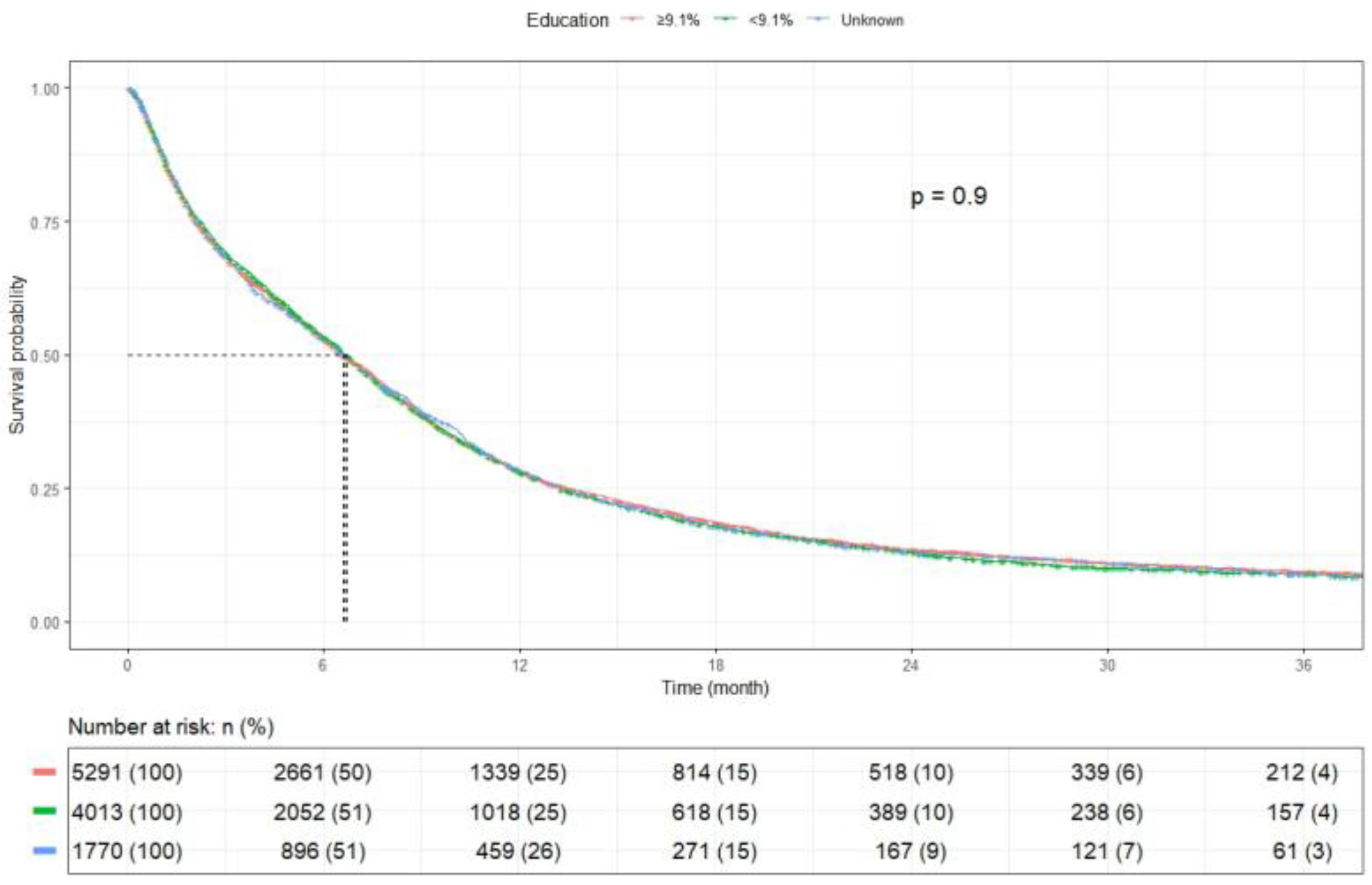

| Education ** | ≥9.1% | 5291 | 6.6 (6.3–6.9) | 0.903 |

| <9.1% | 4013 | 6.7 (6.4–7.0) | ||

| Unknown | 1770 | 6.6 (6.1–7.1) | ||

| Insurance | Private | 2689 | 8.7 (8.3–9.1) | <0.0001 |

| Medicare | 6318 | 5.7 (5.4–6.0) | ||

| Medicaid | 1323 | 7.4 (6.8–7.8) | ||

| Other | 256 | 6.5 (5.6–7.8) | ||

| Uninsured | 488 | 5.6 (4.7–6.7) | ||

| Facility | Academic | 3357 | 7.6 (7.3–7.9) | <0.0001 |

| Integrated network | 2300 | 6.7 (6.2–7.1) | ||

| Community | 5384 | 6.0 (5.8–6.3) | ||

| Unknown | 33 | 9.2 (6.9–30.3) | ||

| Crowfly distance *** | <11.2 miles | 4666 | 6.4 (6.2–6.7) | 0.601 |

| 11.2+ miles | 4713 | 6.9 (6.6–7.2) | ||

| Missing | 1695 | 6.6 (6.1–7.1) | ||

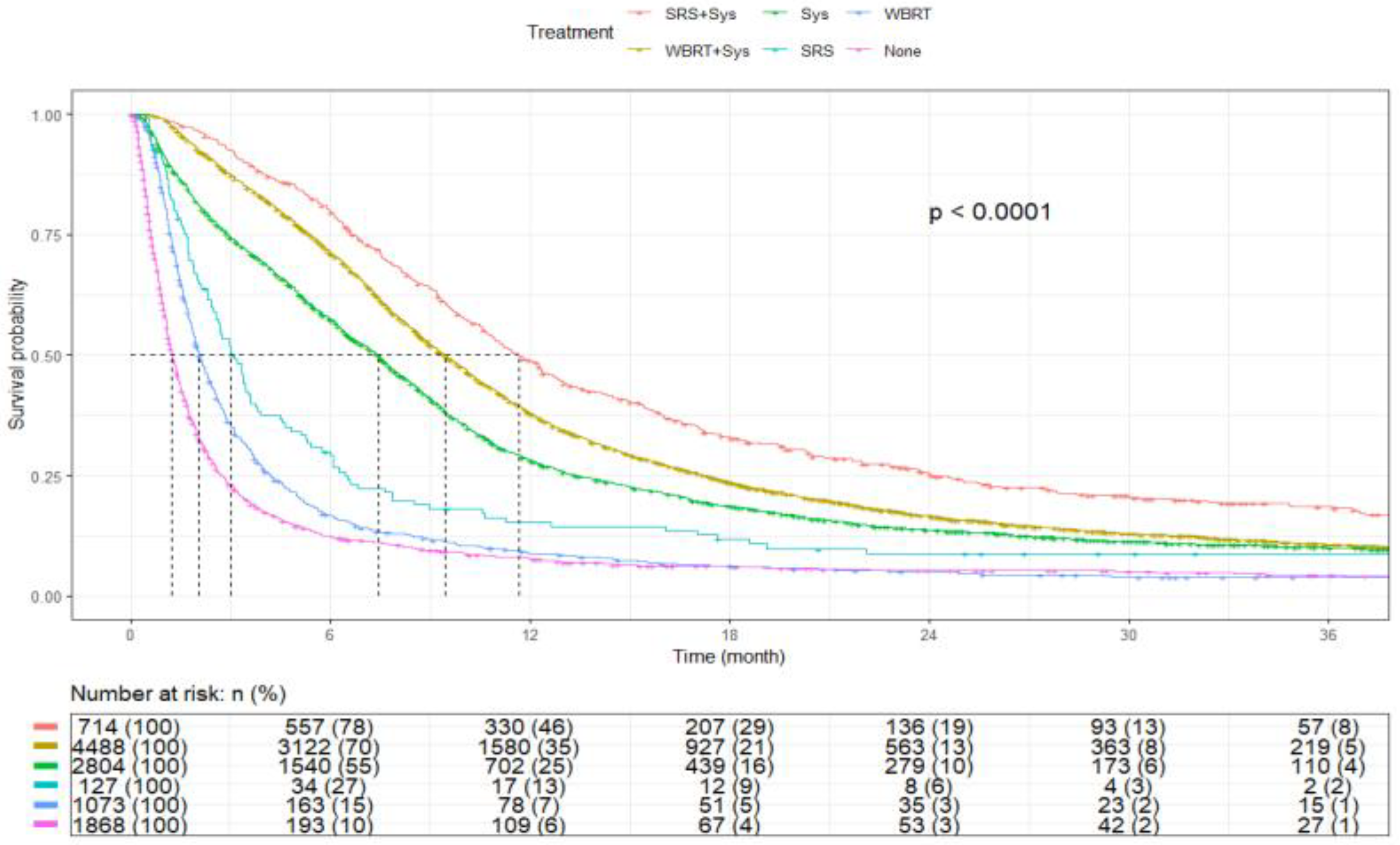

| Treatment | SRS+Sys | 714 | 11.7 (10.9–12.6) | <0.0001 |

| WBRT+Sys | 4488 | 9.4 (9.1–9.7) | ||

| Sys | 2804 | 7.4 (7.1–7.7) | ||

| SRS | 127 | 3.0 (2.6–3.6) | ||

| WBRT | 1073 | 2.0 (1.9–2.2) | ||

| None | 1868 | 1.2 (1.2–1.3) |

| Characteristics | Level | N (%) | HR (Univariable) | HR (Multivariable) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <65 Years | 4805 (43.4) | - | - |

| ≥65 Years | 6269 (56.6) | 1.33 (1.28–1.39, p < 0.001) | 1.13 (1.07–1.19, p < 0.001) | |

| Sex | Male | 5591 (50.5) | - | - |

| Female | 5483 (49.5) | 0.87 (0.83–0.90, p < 0.001) | 0.87 (0.84–0.91, p < 0.001) | |

| Race | White | 9727 (87.8) | - | - |

| Black | 1005 (9.1) | 0.86 (0.80–0.92, p < 0.001) | 0.88 (0.82–0.95, p = 0.001) | |

| Asian | 147 (1.3) | 0.77 (0.65–0.93, p = 0.006) | 0.80 (0.67–0.97, p = 0.022) | |

| Other | 195 (1.8) | 0.90 (0.77–1.06, p = 0.214) | 0.93 (0.79–1.10, p = 0.393) | |

| Ethnicity | Non-Hispanic | 10,591 (95.6) | - | - |

| Hispanic | 483 (4.4) | 0.88 (0.79–0.97, p = 0.011) | 0.87 (0.78–0.96, p = 0.008) | |

| Charlson–Deyo Comorbidity Index | 0 | 6354 (57.4) | - | - |

| 1 | 2659 (24.0) | 1.11 (1.05–1.16, p < 0.001) | 1.12 (1.06–1.17, p < 0.001) | |

| 2–3 | 2061 (18.6) | 1.30 (1.24–1.38, p < 0.001) | 1.21 (1.14–1.28, p < 0.001) | |

| Insurance | Private | 2689 (24.3) | - | - |

| Medicare | 6318 (57.1) | 1.40 (1.33–1.47, p < 0.001) | 1.12 (1.06–1.20, p < 0.001) | |

| Medicaid | 1323 (11.9) | 1.14 (1.06–1.23, p < 0.001) | 1.14 (1.06–1.22, p = 0.001) | |

| Other | 256 (2.3) | 1.18 (1.03–1.36, p = 0.018) | 0.89 (0.77–1.03, p = 0.119) | |

| Uninsured | 488 (4.4) | 1.40 (1.26–1.56, p < 0.001) | 1.26 (1.13–1.40, p < 0.001) | |

| Median Income * | ≥$57,856 | 4720 (42.6) | - | - |

| <$57,856 | 4556 (41.1) | 1.06 (1.02–1.11, p = 0.006) | 1.07 (1.02–1.13, p = 0.011) | |

| Unknown | 1798 (16.2) | 1.03 (0.97–1.10, p = 0.271) | 1.34 (0.90–2.00, p = 0.155) | |

| Education ** | ≥9.1% | 5291 (47.8) | - | - |

| <9.1% | 4013 (36.2) | 1.01 (0.97–1.06, p = 0.651) | 1.03 (0.98–1.09, p = 0.198) | |

| Unknown | 1770 (16.0) | 1.01 (0.95–1.07, p = 0.856) | 0.67 (0.42–1.08, p = 0.101) | |

| Facility Type | Academic | 3357 (30.3) | - | - |

| Integrated network | 2300 (20.8) | 1.20 (1.13–1.27, p < 0.001) | 1.15 (1.09–1.22, p < 0.001) | |

| Community | 5384 (48.6) | 1.25 (1.19–1.31, p < 0.001) | 1.18 (1.12–1.24, p < 0.001) | |

| Unknown | 33 (0.3) | 0.72 (0.48–1.07, p = 0.103) | 0.77 (0.51–1.15, p = 0.200) | |

| Distance *** | 11.2+ miles | 4713 (42.6) | 0.98 (0.94–1.02, p = 0.330) | 1.00 (0.96–1.04, p = 0.965) |

| <11.2 miles | 4666 (42.1) | - | - | |

| Missing | 1695 (15.3) | 1.00 (0.94–1.06, p = 0.908) | 1.13 (0.88–1.46, p = 0.344) | |

| Treatment | SRS+Sys | 714 (6.4) | - | - |

| WBRT+Sys | 4488 (40.5) | 1.28 (1.17–1.40, p < 0.001) | 1.19 (1.09–1.30, p < 0.001) | |

| Sys | 2804 (25.3) | 1.59 (1.45–1.74, p < 0.001) | 1.44 (1.31–1.58, p < 0.001) | |

| SRS | 127 (1.1) | 2.58 (2.10–3.17, p < 0.001) | 2.64 (2.15–3.24, p < 0.001) | |

| WBRT | 1073 (9.7) | 3.82 (3.43–4.24, p < 0.001) | 3.76 (3.39–4.18, p < 0.001) | |

| None | 1868 (16.9) | 5.17 (4.69–5.70, p < 0.001) | 4.86 (4.40–5.36, p < 0.001) | |

| Other Concurrent Metastases | No | 3611 (32.6) | - | - |

| Yes | 7463 (67.4) | 1.50 (1.44–1.57, p < 0.001) | 1.63 (1.55–1.70, p < 0.001) |

| Characteristics | Level | N (%) | HR (Univariable) | HR (Multivariable) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <65 Years | 1513 (41.9) | - | - |

| ≥65 Years | 2098 (58.1) | 1.52 (1.41–1.63, p < 0.001) | 1.28 (1.15–1.42, p < 0.001) | |

| Sex | Male | 1697 (47.0) | - | - |

| Female | 1914 (53.0) | 0.95 (0.88–1.02, p = 0.139) | 0.94 (0.87–1.02, p = 0.119) | |

| Race | White | 3089 (85.5) | - | - |

| Black | 398 (11.0) | 0.82 (0.73–0.93, p = 0.002) | 0.85 (0.75–0.97, p = 0.015) | |

| Asian | 54 (1.5) | 0.66 (0.48–0.92, p = 0.013) | 0.73 (0.52–1.02, p = 0.061) | |

| Other | 70 (1.9) | 0.92 (0.70–1.20, p = 0.546) | 0.91 (0.69–1.21, p = 0.527) | |

| Ethnicity | Non-Hispanic | 3441 (95.3) | - | - |

| Hispanic | 170 (4.7) | 0.97 (0.82–1.16, p = 0.757) | 0.99 (0.82–1.19, p = 0.898) | |

| Comorbid Condition | 0 | 2064 (57.2) | - | - |

| 1 | 868 (24.0) | 1.08 (0.99–1.18, p = 0.098) | 1.11 (1.02–1.22, p = 0.020) | |

| 2–3 | 679 (18.8) | 1.24 (1.13–1.37, p < 0.001) | 1.17 (1.06–1.29, p = 0.002) | |

| Insurance | Private | 830 (23.0) | - | - |

| Medicare | 2085 (57.7) | 1.58 (1.44–1.74, p < 0.001) | 1.15 (1.02–1.29, p = 0.018) | |

| Medicaid | 450 (12.5) | 1.23 (1.07–1.40, p = 0.003) | 1.29 (1.12–1.47, p < 0.001) | |

| Other | 80 (2.2) | 1.21 (0.93–1.57, p = 0.163) | 0.85 (0.65–1.11, p = 0.226) | |

| Uninsured | 166 (4.6) | 1.63 (1.35–1.97, p < 0.001) | 1.49 (1.23–1.80, p < 0.001) | |

| Median Income * | ≥$57,856 | 1512 (41.9) | - | - |

| <$57,856 | 1528 (42.3) | 1.08 (1.00–1.17, p = 0.053) | 1.06 (0.97–1.17, p = 0.199) | |

| Unknown | 571 (15.8) | 1.13 (1.01–1.25, p = 0.031) | 1.39 (0.69–2.79, p = 0.359) | |

| Education ** | ≥9.1% | 1806 (50.0) | - | - |

| <9.1% | 1245 (34.5) | 1.01 (0.93–1.10, p = 0.790) | 1.05 (0.96–1.16, p = 0.300) | |

| Unknown | 560 (15.5) | 1.09 (0.98–1.21, p = 0.127) | 0.89 (0.38–2.09, p = 0.786) | |

| Facility Type | Academic | 1145 (31.7) | - | - |

| Integrated network | 732 (20.3) | 1.28 (1.15–1.42, p < 0.001) | 1.20 (1.08–1.34, p = 0.001) | |

| Community | 1725 (47.8) | 1.32 (1.21–1.44, p < 0.001) | 1.23 (1.13–1.35, p < 0.001) | |

| Unknown | 9 (0.2) | 0.46 (0.17–1.23, p = 0.124) | 0.38 (0.14–1.03, p = 0.057) | |

| Distance (Crowfly) *** | 11.2+ miles | 1585 (43.9) | 0.99 (0.92–1.08, p = 0.875) | 1.01 (0.93–1.09, p = 0.868) |

| <11.2 miles | 1486 (41.2) | - | - | |

| Missing | 540 (15.0) | 1.08 (0.97–1.20, p = 0.180) | 0.89 (0.54–1.48, p = 0.664) | |

| Treatment | SRS+Sys | 298 (8.3) | - | - |

| WBRT+Sys | 1469 (40.7) | 1.25 (1.08–1.45, p = 0.003) | 1.19 (1.03–1.38, p = 0.022) | |

| Sys | 696 (19.3) | 1.38 (1.18–1.62, p < 0.001) | 1.29 (1.10–1.52, p = 0.002) | |

| SRS | 76 (2.1) | 2.97 (2.24–3.93, p < 0.001) | 2.61 (1.97–3.47, p < 0.001) | |

| WBRT | 453 (12.5) | 3.81 (3.22–4.50, p < 0.001) | 3.55 (3.00–4.21, p < 0.001) | |

| None | 619 (17.1) | 4.66 (3.97–5.48, p < 0.001) | 4.26 (3.62–5.02, p < 0.001) |

| Characteristics | Level | N (%) | HR (Univariable) | HR (Multivariable) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <65 Years | 3292 (44.1) | - | - |

| ≥65 Years | 4171 (55.9) | 1.27 (1.21–1.33, p < 0.001) | 1.07 (1.00–1.15, p = 0.039) | |

| Sex | Male | 3894 (52.2) | - | - |

| Female | 3569 (47.8) | 0.84 (0.80–0.89, p < 0.001) | 0.84 (0.80–0.89, p < 0.001) | |

| Race | White | 6638 (88.9) | - | - |

| Black | 607 (8.1) | 0.93 (0.85–1.02, p = 0.134) | 0.89 (0.82–0.98, p = 0.019) | |

| Asian | 93 (1.2) | 0.89 (0.71–1.11, p = 0.310) | 0.87 (0.70–1.09, p = 0.236) | |

| Other | 125 (1.7) | 0.93 (0.76–1.13, p = 0.452) | 0.94 (0.76–1.15, p = 0.539) | |

| Ethnicity | Non-Hispanic | 7150 (95.8) | - | - |

| Hispanic | 313 (4.2) | 0.83 (0.74–0.95, p = 0.005) | 0.80 (0.70–0.92, p = 0.001) | |

| Comorbid Condition | 0 | 4290 (57.5) | - | - |

| 1 | 1791 (24.0) | 1.13 (1.06–1.20, p < 0.001) | 1.12 (1.05–1.19, p < 0.001) | |

| 2–3 | 1382 (18.5) | 1.36 (1.27–1.45, p < 0.001) | 1.22 (1.14–1.30, p < 0.001) | |

| Insurance | Private | 1859 (24.9) | - | - |

| Medicare | 4233 (56.7) | 1.33 (1.25–1.41, p < 0.001) | 1.11 (1.03–1.20, p = 0.005) | |

| Medicaid | 873 (11.7) | 1.12 (1.03–1.23, p = 0.008) | 1.07 (0.98–1.17, p = 0.110) | |

| Other | 176 (2.4) | 1.18 (1.00–1.39, p = 0.052) | 0.91 (0.77–1.08, p = 0.267) | |

| Uninsured | 322 (4.3) | 1.33 (1.17–1.51, p < 0.001) | 1.16 (1.02–1.32, p = 0.026) | |

| Median Income * | ≥$57,856 | 3208 (43.0) | - | - |

| <$57,856 | 3028 (40.6) | 1.06 (1.01–1.12, p = 0.025) | 1.07 (1.01–1.14, p = 0.028) | |

| Unknown | 1227 (16.4) | 0.99 (0.92–1.06, p = 0.707) | 1.35 (0.82–2.21, p = 0.236) | |

| Education ** | ≥9.1% | 3485 (46.7) | - | - |

| <9.1% | 2768 (37.1) | 0.99 (0.94–1.04, p = 0.733) | 1.02 (0.96–1.09, p = 0.481) | |

| Unknown | 1210 (16.2) | 0.95 (0.89–1.02, p = 0.164) | 0.62 (0.35–1.09, p = 0.096) | |

| Facility Type | Academic | 2212 (29.6) | - | - |

| Integrated network | 1568 (21.0) | 1.15 (1.07–1.23, p < 0.001) | 1.12 (1.05–1.21, p = 0.001) | |

| Community | 3659 (49.0) | 1.20 (1.14–1.27, p < 0.001) | 1.15 (1.09–1.22, p < 0.001) | |

| Unknown | 24 (0.3) | 0.77 (0.50–1.20, p = 0.249) | 1.03 (0.66–1.61, p = 0.887) | |

| Distance (Crowfly) *** | 11.2+ miles | 3128 (41.9) | 0.98 (0.93–1.04, p = 0.501) | 1.00 (0.94–1.05, p = 0.863) |

| <11.2 miles | 3180 (42.6) | - | - | |

| Missing | 1155 (15.5) | 0.96 (0.89–1.03, p = 0.242) | 1.19 (0.88–1.60, p = 0.252) | |

| Treatment | SRS+Sys | 416 (5.6) | - | - |

| WBRT+Sys | 3019 (40.5) | 1.21 (1.08–1.36, p = 0.001) | 1.19 (1.07–1.34, p = 0.002) | |

| Sys | 2108 (28.2) | 1.52 (1.36–1.71, p < 0.001) | 1.51 (1.34–1.70, p < 0.001) | |

| SRS | 51 (0.7) | 2.62 (1.93–3.57, p < 0.001) | 2.61 (1.91–3.55, p < 0.001) | |

| WBRT | 620 (8.3) | 4.08 (3.56–4.67, p < 0.001) | 3.91 (3.41–4.47, p < 0.001) | |

| None | 1249 (16.7) | 5.45 (4.82–6.17, p < 0.001) | 5.23 (4.63–5.92, p < 0.001) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qidwai, K.A.; Sarfraz, Z.; Mustafayev, K.; Hodgson, L.C.; Maharaj, A.; Sen, T.; Ranjan, T.; Ahluwalia, M.S. Survival Determinants and Treatment Outcomes of Patients with Small Cell Lung Cancer and Brain Metastases: A U.S. National Analysis. Cancers 2025, 17, 3833. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233833

Qidwai KA, Sarfraz Z, Mustafayev K, Hodgson LC, Maharaj A, Sen T, Ranjan T, Ahluwalia MS. Survival Determinants and Treatment Outcomes of Patients with Small Cell Lung Cancer and Brain Metastases: A U.S. National Analysis. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3833. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233833

Chicago/Turabian StyleQidwai, Khalid Ahmad, Zouina Sarfraz, Khalis Mustafayev, Lydia C. Hodgson, Arun Maharaj, Triparna Sen, Tulika Ranjan, and Manmeet S. Ahluwalia. 2025. "Survival Determinants and Treatment Outcomes of Patients with Small Cell Lung Cancer and Brain Metastases: A U.S. National Analysis" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3833. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233833

APA StyleQidwai, K. A., Sarfraz, Z., Mustafayev, K., Hodgson, L. C., Maharaj, A., Sen, T., Ranjan, T., & Ahluwalia, M. S. (2025). Survival Determinants and Treatment Outcomes of Patients with Small Cell Lung Cancer and Brain Metastases: A U.S. National Analysis. Cancers, 17(23), 3833. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233833