Stage III NSCLC Treatment Patterns in Spain: A Population-Based Study of the GOECP-SEOR

Simple Summary

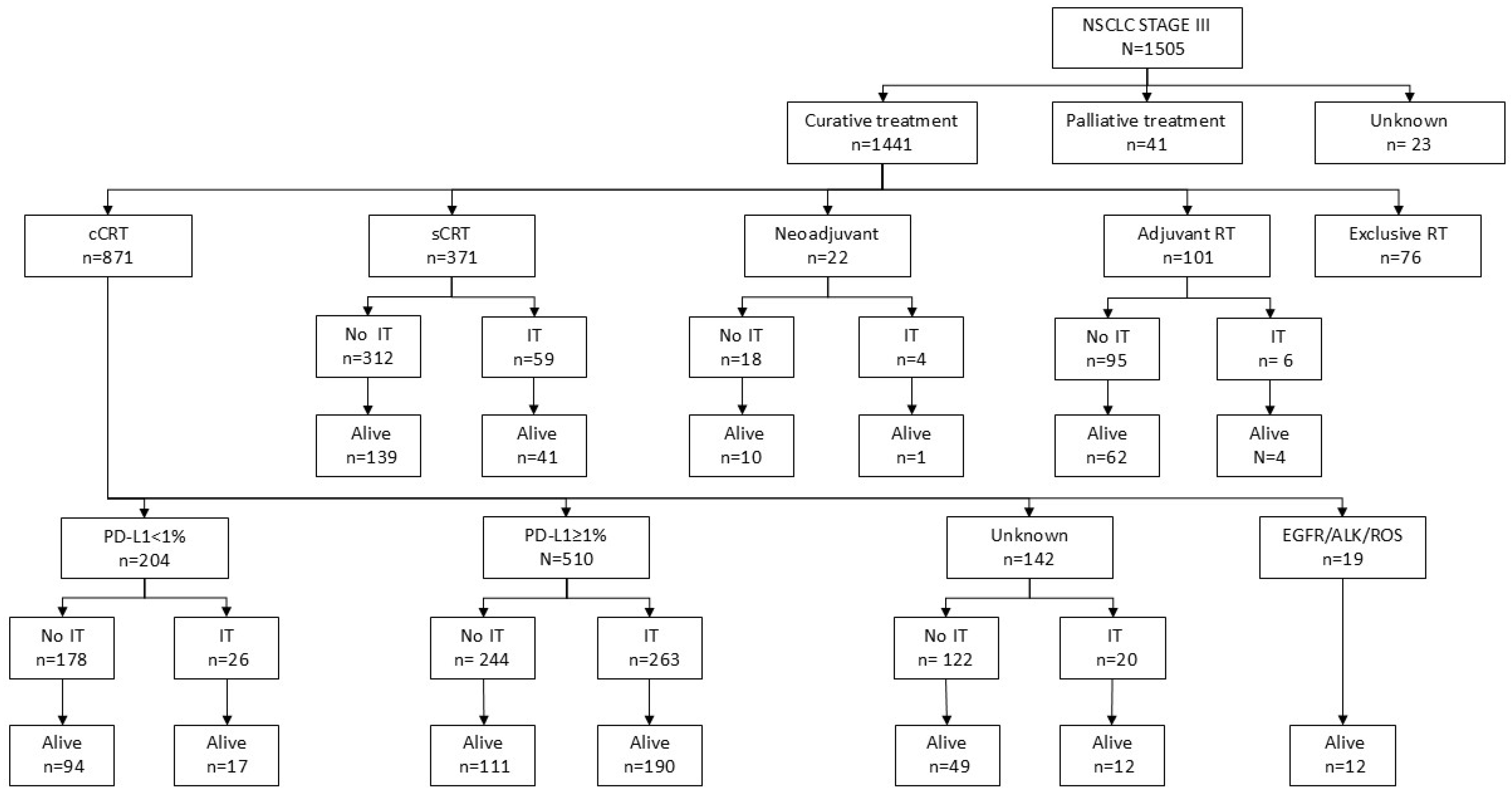

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Problem Statement

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

Specific Objectives

- To characterize the management approaches used for NSCLC-SIII, including radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and consolidation strategies.

- To assess the accessibility of Durvalumab maintenance.

2.2. Selection of Patients

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Ethics Committee Approval

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of Patients and Disease

3.2. Treatment Characteristics

3.3. Local Control

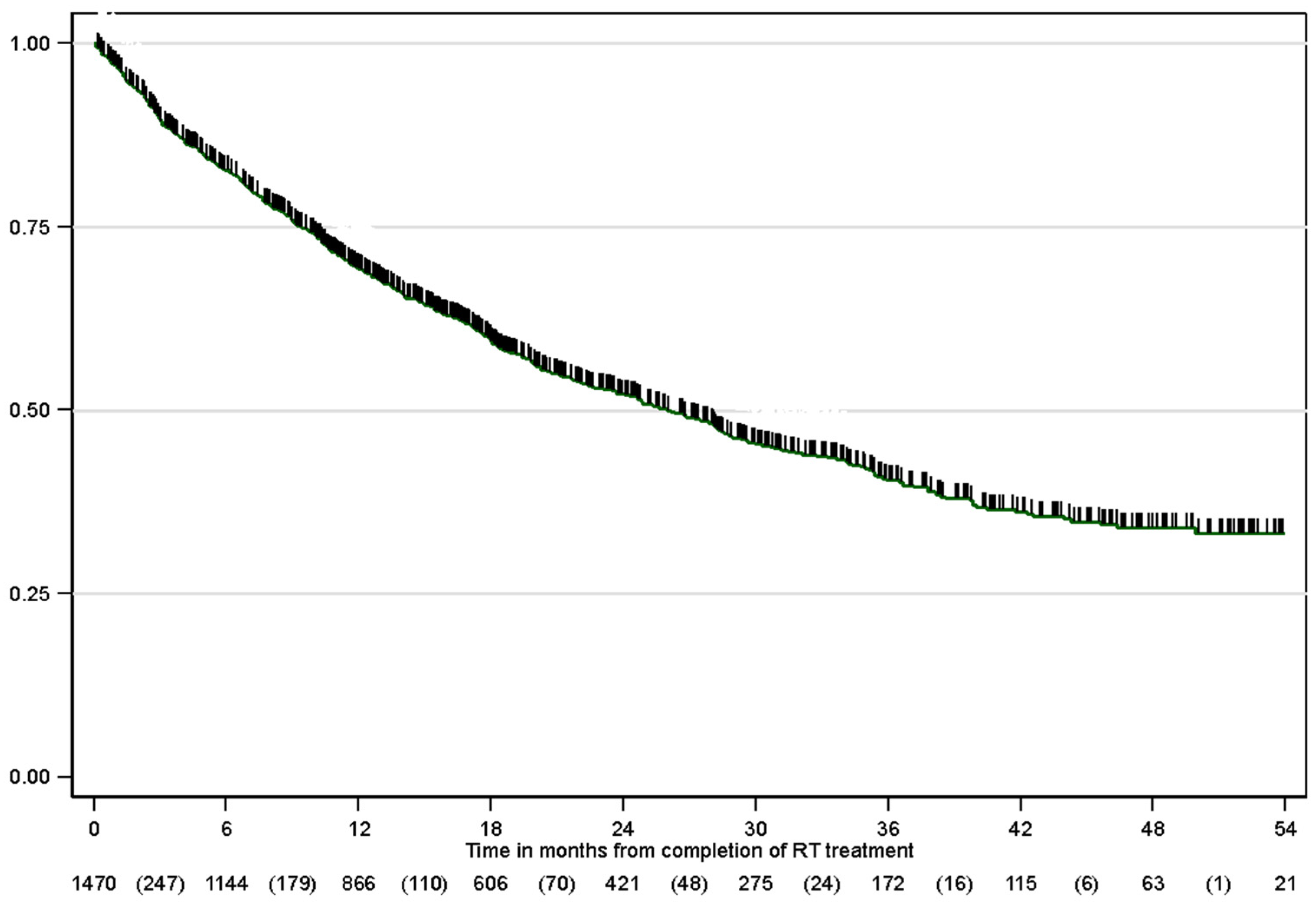

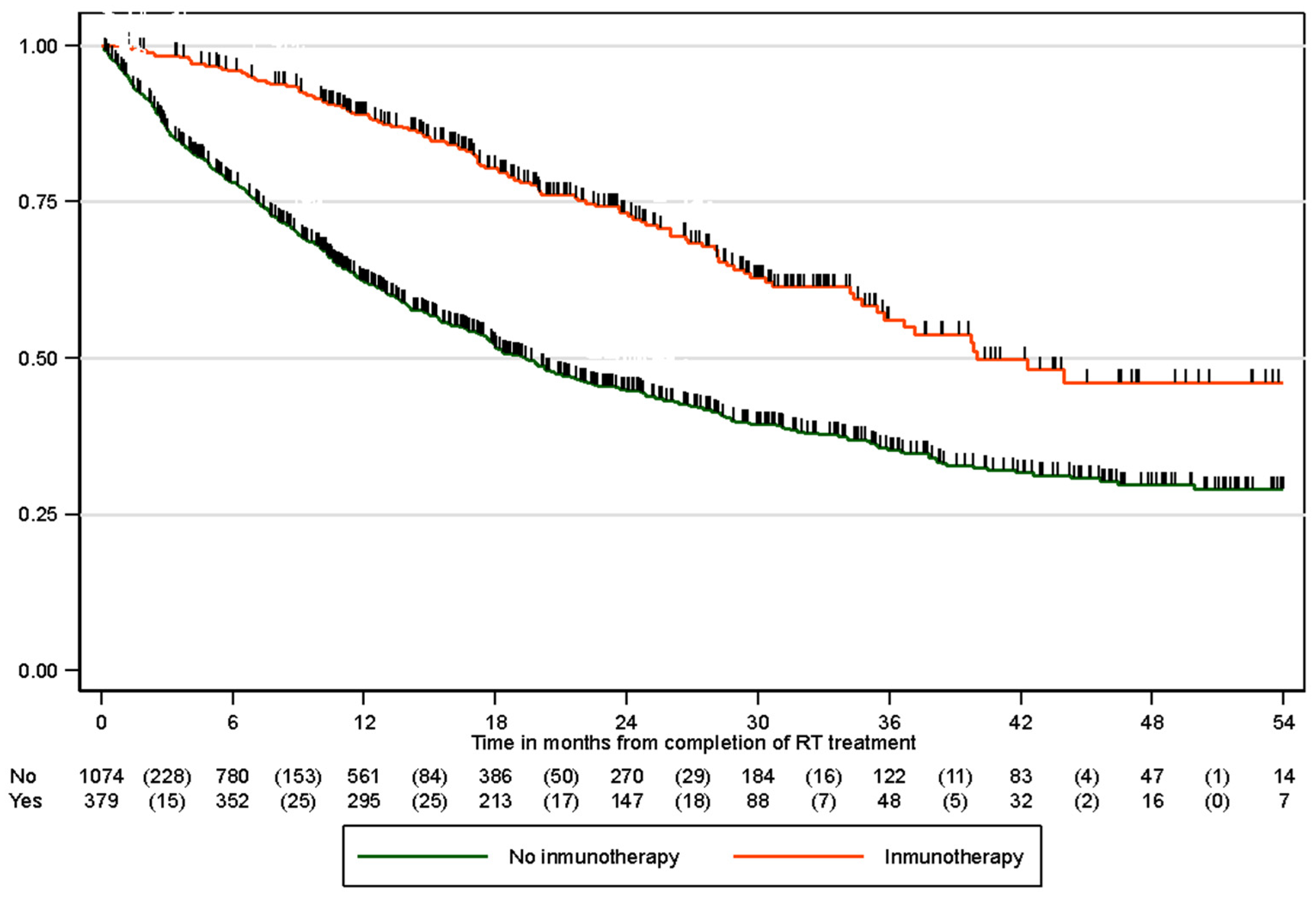

3.4. Overall Survival

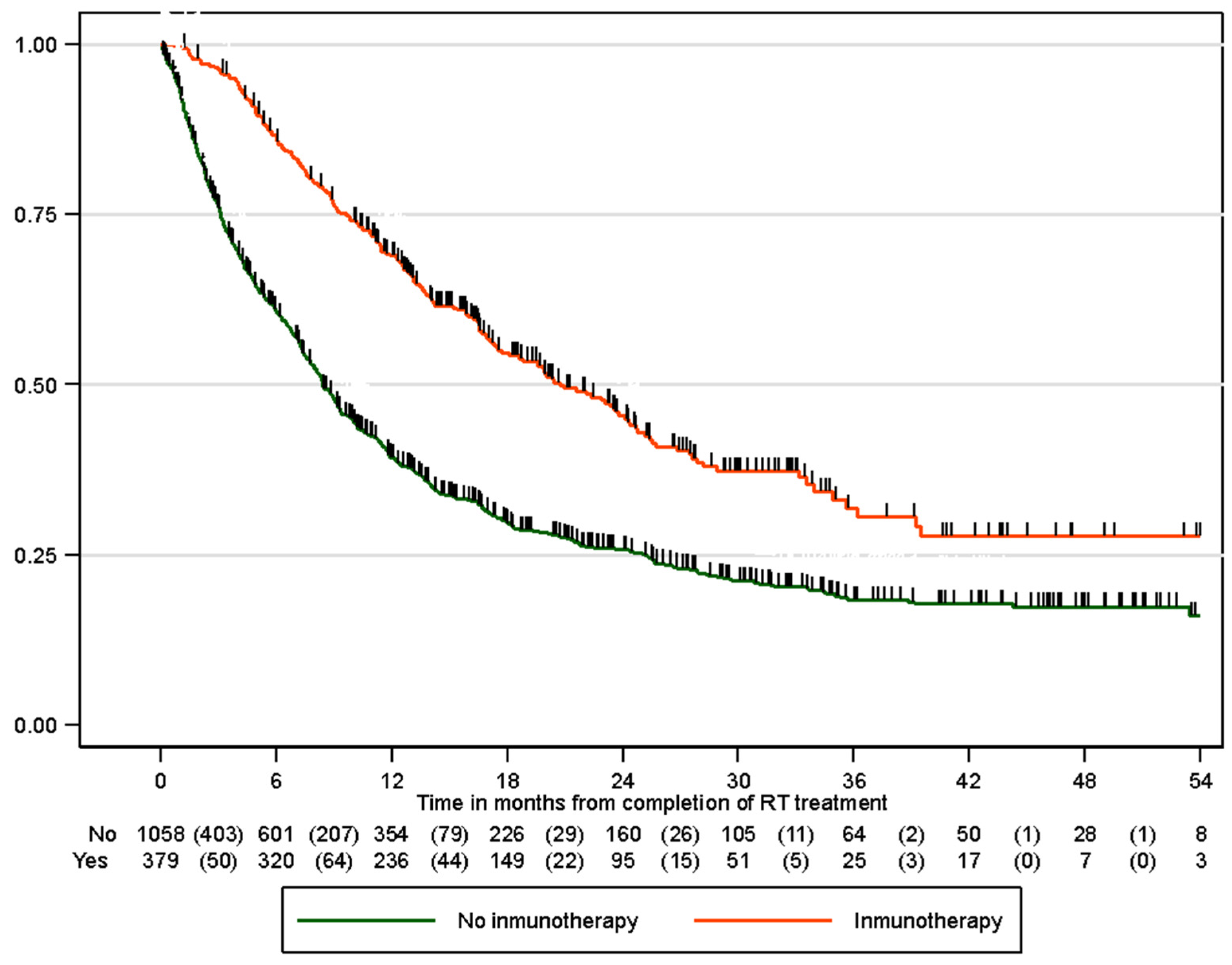

3.5. Progression-Free Survival

3.6. Toxicity

4. Discussion

5. Future Perspectives and Recommendations

6. Study Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ramnath, N.; Dilling, T.J.; Harris, L.J.; Kim, A.W.; Michaud, G.C.; Balekian, A.A.; Diekemper, R.; Detterbeck, F.C.; Arenberg, D.A. Treatment of stage III non-small cell lung cancer: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American college of chest physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2013, 143, e314S–e340S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, L.G.; Haines, C.; Perkel, R.; Enck, R.E. Lung cancer: Diagnosis and management. Am. Fam. Physician 2007, 75, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adizie, J.B.; Khakwani, A.; Beckett, P.; Navani, N.; West, D.; Woolhouse, I.; Harden, S.V. Stage III non-small cell lung cancer management in England. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 31, 688–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simone, C.B.; Bradley, J.; Chen, A.B.; Daly, M.E.; Louie, A.V.; Robinson, C.G.; Videtic, G.M.M.; Rodrigues, G. ASTRO radiation therapy summary of the ASCO guideline on management of stage III non-small cell lung cancer. Pract. Radiat. Oncol. 2023, 13, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faivre-Finn, C.; Vicente, D.; Kurata, T.; Planchard, D.; Paz-Ares, L.; Vansteenkiste, J.F.; Spigel, D.R.; Garassino, M.C.; Reck, M.; Senan, S.; et al. Four-year survival with durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy in stage III NSCLC-an update from the PACIFIC trial. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2021, 16, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schild, S.E.; Hillman, S.L.; Tan, A.D.; Ross, H.J.; McGinnis, W.L.; Garces, Y.A.; Graham, D.L.; Adjei, A.A.; Jett, J.R. Long-term results of a trial of concurrent chemotherapy and escalating doses of radiation for unresectable non-small cell lung cancer: NCCTG N0028 (alliance). J. Thorac. Oncol. 2017, 12, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rengan, R.; Rosenzweig, K.E.; Venkatraman, E.; Koutcher, L.A.; Fox, J.L.; Nayak, R.; Amols, H.; Yorke, E.; Jackson, A.; Ling, C.C.; et al. Improved local control with higher doses of radiation in large-volume stage III non-small-cell lung cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2004, 60, 741–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Sun, X.; Li, M.; Yu, J.; Ren, R.; Yu, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, R.; Li, B.; et al. A randomized study of involved-field irradiation versus elective nodal irradiation in combination with concurrent chemotherapy for inoperable stage III nonsmall cell lung cancer. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 30, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, J.D.; Paulus, R.; Komaki, R.; Masters, G.; Blumenschein, G.; Schild, S.; Bogart, J.; Hu, C.; Forster, K.; Magliocco, A.; et al. Standard-dose versus high-dose conformal radiotherapy with concurrent and consolidation carboplatin plus paclitaxel with or without cetuximab for patients with stage IIIA or IIIB non-small-cell lung cancer (RTOG 0617): A randomised, two-by-two factorial phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landman, Y.; Jacobi, O.; Kurman, N.; Yariv, O.; Peretz, I.; Rotem, O.; Dudnik, E.; Zer, A.; Allen, A.M. Durvalumab after concurrent chemotherapy and high-dose radiotherapy for locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer. OncoImmunology 2021, 10, 1959979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senan, S.; Brade, A.; Wang, L.-H.; Vansteenkiste, J.; Dakhil, S.; Biesma, B.; Aguillo, M.M.; Aerts, J.; Govindan, R.; Rubio-Viqueira, B.; et al. PROCLAIM: Randomized phase III trial of pemetrexed-cisplatin or etoposide-cisplatin plus thoracic radiation therapy followed by consolidation chemotherapy in locally advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 953–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, N.; Neubauer, M.; Yiannoutsos, C.; McGarry, R.; Arseneau, J.; Ansari, R.; Reynolds, C.; Govindan, R.; Melnyk, A.; Fisher, W.; et al. Phase III study of cisplatin, etoposide, and concurrent chest radiation with or without consolidation docetaxel in patients with inoperable stage III non-small-cell lung cancer: The hoosier oncology group and U.S. Oncology. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 5755–5760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.S.; Ahn, Y.C.; Kim, J.-H.; Lee, C.G.; Cho, E.K.; Lee, K.C.; Chen, M.; Kim, D.-W.; Kim, H.-K.; Min, Y.J.; et al. Multinational randomized phase III trial with or without consolidation chemotherapy using docetaxel and cisplatin after concurrent chemoradiation in inoperable stage III non-small-cell lung cancer: KCSG-LU05-04. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 2660–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, K.; Chansky, K.; Gaspar, L.E.; Albain, K.S.; Jett, J.; Ung, Y.C.; Lau, D.H.M.; Crowley, J.J.; Gandara, D.R. Phase III trial of maintenance gefitinib or placebo after concurrent chemoradiotherapy and docetaxel consolidation in inoperable stage III non–small-cell lung cancer: SWOG S0023. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 2450–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, J.E.; Villegas, A.; Daniel, D.; Vicente, D.; Murakami, S.; Hui, R.; Kurata, T.; Chiappori, A.; Lee, K.H.; Cho, B.C.; et al. Three-year overall survival with durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy in stage III NSCLC—Update from PACIFIC. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2020, 15, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonia, S.J.; Villegas, A.; Daniel, D.; Vicente, D.; Murakami, S.; Hui, R.; Kurata, T.; Chiappori, A.; Lee, K.H.; de Wit, M.; et al. Overall survival with durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy in stage III NSCLC. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2342–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonia, S.J.; Villegas, A.; Daniel, D.; Vicente, D.; Murakami, S.; Hui, R.; Yokoi, T.; Chiappori, A.; Lee, K.H.; de Wit, M.; et al. Durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy in stage III non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1919–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spigel, D.R.; Faivre-Finn, C.; Gray, J.E.; Vicente, D.; Planchard, D.; Paz-Ares, L.G.; Vansteenkiste, J.F.; Garassino, M.C.; Hui, R.; Quantin, X.; et al. Five-year survival outcomes with durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy in unresectable stage III NSCLC: An update from the PACIFIC trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 8511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, G.; Oya, Y.; Taniguchi, Y.; Kawachi, H.; Daichi, F.; Matsumoto, H.; Iwasawa, S.; Suzuki, H.; Niitsu, T.; Miyauchi, E.; et al. Real-world survey of pneumonitis and its impact on durvalumab consolidation therapy in patients with non-small cell lung cancer who received chemoradiotherapy after durvalumab approval (HOPE-005/CRIMSON). Lung Cancer 2021, 161, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mir, N.A.; Hull, O.; Bothwell, S.; Das, D. Guideline concordance with durvalumab in unresectable stage III non-small cell lung cancer: A single center veterans hospital experience. Fed. Pract. 2021, 38, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botticella, A.; Mezquita, L.; Le Pechoux, C.; Planchard, D. Durvalumab for stage III non-small-cell lung cancer patients: Clinical evidence and real-world experience. Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. 2019, 13, 1753466619885530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noronha, V.; Talreja, V.T.; Patil, V.; Joshi, A.; Menon, N.; Mahajan, A.; Janu, A.; Prabhash, K. Real-world experience of patients with inoperable, stage III non-small-cell lung cancer treated with durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy: Indian experience. South Asian J. Cancer 2020, 9, 180–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garon, E.B.; Rizvi, N.A.; Hui, R.; Leighl, N.; Balmanoukian, A.S.; Eder, J.P.; Patnaik, A.; Aggarwal, C.; Gubens, M.; Horn, L.; et al. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 2018–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, J.; de Jaeger, K.; Hendriks, L.E.L.; van der Sangen, M.; Terhaard, C.; Siesling, S.; De Ruysscher, D.; Struikmans, H.; Aarts, M.J. Trends and variations in treatment of stage I-III non-small cell lung cancer from 2008 to 2018: A nationwide population-based study from the Netherlands. Lung Cancer 2021, 155, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, N.; Perol, M.; Simon, G.; Valette, C.A.; Gervais, R.; Debieuvre, D.; Schott, R.; Quantin, X.; Coudert, B.; Lena, H.; et al. Treatment strategies for unresectable locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer in the real-life ESME cohort. Lung Cancer 2021, 162, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provencio, M.; Nadal, E.; Insa, A.; García-Campelo, M.R.; Casal-Rubio, J.; Dómine, M.; Majem, M.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Martínez-Martí, A.; De Castro Carpeño, J.; et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy and nivolumab in resectable non-small-cell lung cancer (NADIM): An open-label, multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 1413–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Pechoux, C.; Pourel, N.; Barlesi, F.; Lerouge, D.; Antoni, D.; Lamezec, B.; Nestle, U.; Boisselier, P.; Dansin, E.; Paumier, A.; et al. Postoperative radiotherapy versus no postoperative radiotherapy in patients with completely resected non-small-cell lung cancer and proven mediastinal N2 involvement (Lung ART, IFCT 0503): An open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hergert, J. Real-World PFS Benefit Reported with Durvalumab Regimen in Unresectable Stage III NSCLC. Available online: https://www.onclive.com/view/real-world-pfs-benefit-reported-with-pacific-regimen-in-unresectable-stage-iii-nsclc (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Girard, N.; Bar, J.; Garrido, P.; Garassino, M.C.; McDonald, F.; Mornex, F.; Filippi, A.R.; Smit, H.J.M.; Peters, S.; Field, J.K.; et al. Treatment characteristics and real-world progression-free survival in patients with unresectable stage III NSCLC who received durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy: Findings from the PACIFIC-R study. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2023, 18, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterhouse, D.; Yong, C.; Frankart, A.; Brannman, L.; Mulrooney, T.; Robert, N.; Aguilar, K.M.; Ndukum, J.; Cotarla, I. Durvalumab real-world treatment patterns and outcomes in patients with stage III non-small-cell lung cancer treated in a US community setting. Future Oncol. 2023, 19, 1905–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damhuis, R.; Bahce, I.; Senan, S. Association between PD-L1 score and the outcomes of consolidation durvalumab in a large nationwide series of patients with stage III NSCLC treated with chemoradiotherapy. Clin. Lung Cancer 2024, 25, 683–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filippi, A.R.; Bar, J.; Chouaid, C.; Christoph, D.C.; Field, J.K.; Fietkau, R.; Garassino, M.C.; Garrido, P.; Haakensen, V.D.; Kao, S.; et al. Real-world outcomes with durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy in patients with unresectable stage III NSCLC: Interim analysis of overall survival from PACIFIC-R. ESMO Open 2024, 9, 103464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, F.; Senan, S.; Faivre-Finn, C.; Hatton, M. Curative radiotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer: Practice changing and changing practice? Clin. Oncol. 2019, 31, 678–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chun, S.G.; Hu, C.; Choy, H.; Komaki, R.U.; Timmerman, R.D.; Schild, S.E.; Bogart, J.A.; Dobelbower, M.C.; Bosch, W.; Galvin, J.M.; et al. Impact of intensity-modulated radiation therapy technique for locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: A secondary analysis of the NRG oncology RTOG 0617 randomized clinical trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuang, Y.; Pierce, C.M.; Chang, H.-C.; Sosinsky, A.Z.; Deitz, A.C.; Keller, S.M.; Samkari, A.; Uyei, J. Chemoradiation-induced pneumonitis in patients with unresectable stage III non-small cell lung cancer: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Lung Cancer 2022, 174, 174–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total N = 1505 | No Immunotherapy N = 1115 | Immunotherapy * N = 390 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis, mean (SD) | 67.1 (9.1) | 67.8 (9.3) | 65.1 (8.1) | 0.411 |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.54 | |||

| Female | 358 (24.1) | 251 (22.8) | 107 (27.7) | |

| Male | 1127 (75.9) | 848 (77.2) | 279 (72.3) | |

| Performance Status, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| 0 | 754 (52.2) | 526 (48.9) | 228 (61.6) | |

| 1 | 541 (37.4) | 421 (39.2) | 120 (32.4) | |

| 2 | 110 (7.6) | 96 (8.9) | 14 (3.8) | |

| 3 | 8 (0.6) | 8 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Missing | 32 (2.2) | 24 (2.2) | 8 (2.2) | |

| Smoking status, n (%) | 0.039 | |||

| Active smoker | 575 (38.3) | 410 (36.8) | 165 (42.5) | |

| Former smoker | 820 (54.6) | 630 (56.6) | 190 (49.0) | |

| Never smoker | 81 (5.4) | 58 (5.2) | 23 (5.9) | |

| Missing | 25 (1.7) | 15 (1.3) | 10 (2.6) | |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | 0.04 | |||

| Cardiovascular | 706 (46.9) | 542 (48.6) | 164 (42.1) | |

| Respiratory | 508 (33.8) | 406 (36.4) | 102 (26.2) | |

| Metabolic | 524 (34.8) | 409 (36.7) | 115 (29.5) | |

| Previous tumors | 234 (15.5) | 179 (16.1) | 55 (14.1) | |

| Other | 310 (20.6) | 244 (21.9) | 66 (16.9) | |

| Histology, n (%) | 0.14 | |||

| Epidermoid | 711 (47.2) | 524 (47.0) | 187 (47.9) | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 644 (42.8) | 466 (41.8) | 178 (45.6) | |

| Carcinoma | 67 (4.5) | 55 (4.9) | 12 (3.1) | |

| Large cells | 40 (2.7) | 35 (3.1) | 5 (1.3) | |

| Others | 18 (1.2) | 15 (1.3) | 3 (0.8) | |

| Missing | 25 (1.7) | 20 (1.8) | 5 (1.3) | |

| Mutations, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Unknown | 316 (21.0) | 288 (25.8) | 28 (7.2) | |

| PD-L1 Unknown | 652 (43.3) | 586 (52.6) | 66 (16.9) | |

| PDL1 < 1% | 228 (15.1) | 228 (20.4) | - | |

| PDL1 > 1–50% | 383 (25.4) | 192 (17.2) | 191 (49) | |

| PDL1 > 50% | 242 (16.1) | 109 (9.8) | 133 (34.1) | |

| EGFR | 32 (2.1) | 27 (2.4) | 5 (1.3) | |

| ALK | 16 (1.1) | 15 (1.3) | 1 (0.3) | |

| ROS1 | 5 (0.3) | 5 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| T, n (%) | 0.191 | |||

| Tx | 28 (1.9) | 17 (1.5) | 11 (2.8) | |

| T0 | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Tis | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| T1a (mi) | 10 (0.7) | 7 (0.6) | 3 (0.8) | |

| T1a | 15 (1.0) | 14 (1.3) | 1 (0.3) | |

| T1b | 75 (5.0) | 65 (5.8) | 10 (2.6) | |

| T1c | 86 (5.7) | 66 (5.9) | 20 (5.1) | |

| T2 | 64 (4.3) | 45 (4.0) | 19 (4.9) | |

| T2a | 96 (6.4) | 74 (6.6) | 22 (5.7) | |

| T2b | 82 (5.5) | 58 (5.2) | 24 (6.2) | |

| T3 | 315 (21.0) | 235 (21.1) | 80 (20.6) | |

| T4 | 730 (48.6) | 532 (47.7) | 198 (51.0) | |

| Missing | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.5) | |

| N, n (%) | 0.711 | |||

| N0 | 172 (11.5) | 130 (11.7) | 42 (10.8) | |

| N1 | 115 (7.7) | 89 (8.0) | 26 (6.7) | |

| N2 | 874 (58.2) | 641 (57.6) | 233 (60.1) | |

| N3 | 331 (22.1) | 245 (22.0) | 86 (22.2) | |

| Nx | 9 (0.6) | 8 (0.7) | 1 (0.3) | |

| M, n (%) | 0.307 | |||

| M0 | 1442 (99.0) | 1066 (98.9) | 376 (99.2) | |

| M1a | 4 (0.3) | 3 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | |

| M1b | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.3) | |

| Mx | 9 (0.6) | 8 (0.7) | 1 (0.3) | |

| Missing | 48 (3.2) | 37 (3.3) | 11 (2.8) | |

| TNM stage, n (%) | 0.077 | |||

| IIIA T1a–c N2 M0 | 199 (13.2) | 162 (14.5) | 37 (9.5) | |

| IIIA T2a–b N2 M0 | 185 (12.3) | 138 (12.4) | 47 (12.0) | |

| IIIA T3 N1 M0 | 46 (3.1) | 40 (3.6) | 6 (1.5) | |

| IIIA T4 N0 M0 | 168 (11.2) | 127 (11.4) | 41 (10.5) | |

| IIIA T4 N1 M0 | 67 (4.4) | 47 (4.2) | 20 (5.1) | |

| IIIB T1a–c N3 M0 | 60 (4.0) | 48 (4.3) | 12 (3.1) | |

| IIIB T2a–b N3 | 58 (3.8) | 40 (3.6) | 18 (4.6) | |

| IIIB T3 N2 M0 | 185 (12.3) | 129 (11.6) | 56 (14.4) | |

| IIIB T4 N2 M0 | 355 (23.6) | 255 (22.9) | 100 (25.6) | |

| IIIC T3 N3 M0 | 66 (4.4) | 44 (3.9) | 22 (5.6) | |

| IIIC T4 N3 M0 | 110 (7.3) | 82 (7.3) | 28 (7.2) |

| Total N = 1505 | No Immunotherapy N = 1115 | Immunotherapy * N = 390 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intention of radiotherapy treatment | <0.001 | |||

| Neoadjuvant radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy, n (%) | 22 (1.5) | 18 (1.6) | 4 (1.0) | |

| Sequential radical radiotherapy, n (%) | 371 (24.7) | 312 (28.0) | 59 (15.1) | |

| Concurrent radical radiotherapy, n (%) | 871 (57.9) | 556 (49.9) | 315 (80.8) | |

| Adjuvant postsurgical radiotherapy N2, n (%) | 84 (5.6) | 79 (7.1) | 5 (1.3) | |

| Adjuvant postsurgical radiotherapy R1, n (%) | 17 (1.1) | 16 (1.4) | 1 (0.3) | |

| Palliative radiotherapy, n (%) | 20 (1.3) | 18 (1.6) | 2 (0.5) | |

| Exclusive radical radiotherapy, n (%) | 76 (5.0) | 76 (6.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Unknown, n (%) | 23 (1.5) | 22 (2.0) | 1 (0.3) | |

| Missing, n (%) | 21 (1.4) | 18 (1.6) | 3 (0.8) | |

| Time on radiotherapy in days, median (IQR) | 44.0 (40.0; 49.0) | 44.0 (39.0; 49.0) | 45.0 (42.0; 49.0) | 0.521 |

| Total dose of radiotherapy, mean (SD) | 60.2 (7.5) | 59.5 (8.2) | 62.1 (4.7) | <0.001 |

| Type of radiotherapy, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| 3D | 307 (20.4) | 252 (22.6) | 55 (14.1) | |

| IMRT/VMAT | 1171 (77.8) | 841 (75.4) | 330 (84.6) | |

| Missing | 27 (1.8) | 22 (2.0) | 5 (1.3) | |

| Control of IGRT with CBCT, n (%) | 0.059 | |||

| No | 178 (11.8) | 142 (12.7) | 36 (9.2) | |

| Yes | 1315 (87.4) | 962 (86.3) | 353 (90.5) | |

| Missing | 12 (0.8) | 11 (1.0) | 1 (0.3) | |

| Number of chemotherapy cycles, mean (SD) | 4.0 (2.1) | 4.0 (2.3) | 4.1 (1.7) | 0.458 |

| Scheme, n (%) | 0.280 | |||

| Platinum double | 1107 (73.6) | 788 (70.7) | 319 (81.8) | |

| Others | 248 (16.5) | 185 (16.6) | 63 (16.2) | |

| Missing | 150 (10.0) | 142 (12.7) | 8 (2.1) | |

| Time on chemotherapy, median (IQR) | 63.0 (42.0–77.0) | 63.0 (43.0–79.0) | 58.0 (42.0–76.0) | 0.343 |

| Surgery, n (%) | 157 (10.4) | 146 (13.1) | 11 (2.8) | <0.001 |

| Missing | 16 (1.1) | 12 (1.1) | 4 (1.0) | |

| Intention, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Radical | 144 (9.6) | 136 (12.2) | 8 (2.1) | |

| Rescue | 10 (0.7) | 10 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Palliative/Biopsy | 5 (0.3) | 2 (0.2) | 3 (0.8) | |

| Surgery type, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Pneumonectomy | 17 (1.1) | 17 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Lobectomy | 126 (8.4) | 120 (10.8) | 6 (1.5) | |

| Atypical resection | 15 (1.0) | 10 (0.9) | 5 (1.3) |

| Total N = 871 | No Immunotherapy N = 556 | Immunotherapy * N = 315 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relapse | 459 (52.7) | 314 (56.5) | 145 (46.0) | 0.008 |

| Local | 179 (20.6) | 120 (21.6) | 59 (18.7) | 0.026 |

| Local (within previous RT field) | 116 (13.3) | 78 (14.0) | 38 (12.1) | 0.11 |

| Local (out of field of previous RT) | 86 (9.9) | 56 (10.1) | 30 (9.5) | 0.613 |

| Distance | 202 (23.2) | 136 (24.5) | 66 (21.0) | 0.052 |

| Local and distance | 78 (9.0) | 58 (10.4) | 20 (6.3) | 0.13 |

| Local (within previous RT field) | 57 (6.5) | 42 (7.5) | 15 (4.8) | 0.376 |

| Local (out of field of previous RT) | 47 (5.4) | 35 (6.3) | 12 (3.8) | 0.161 |

| Metastasis | ||||

| Lung | 68 (7.8) | 54 (9.7) | 14 (4.4) | 0.036 |

| Liver | 44 (5.1) | 33 (5.9) | 11 (3.5) | 0.053 |

| CNS | 94 (10.8) | 66 (11.9) | 28 (8.9) | 0.829 |

| Bone | 81 (9.3) | 56 (10.1) | 25 (7.9) | 0.944 |

| Suprarenal | 44 (5.1) | 33 (5.9) | 11 (3.5) | 0.328 |

| Lymph nodes | 54 (6.2) | 43 (7.7) | 11 (3.5) | 0.031 |

| Others | 25 (2.9) | 14 (2.5) | 11 (3.5) | 0.883 |

| Immunotherapy N = 315 | No Immunotherapy N = 556 | |

|---|---|---|

| (a) Overall Survival | ||

| 6 months | 96.0% (93.1%, 97.7%) | 78.2% (74.5%, 81.5%) |

| 12 months | 89.0% (84.8%, 92.1%) | 63.4% (59.1%, 67.4%) |

| 24 months | 73.6% (67.4%, 78.7%) | 46.2% (41.5%, 50.8%) |

| (b) Progression-Free Survival | ||

| 6 months | 88.1% (83.9%, 91.3%) | 61.0% (56.7%, 65.0%) |

| 12 months | 70.2% (64.6%, 75.1%) | 39.1% (34.9%, 43.4%) |

| 24 months | 45.4% (39.0%, 51.6%) | 25.5% (21.6%, 29.6%) |

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p Value | HR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Immunotherapy | 0.42 (0.35, 0.52) | <0.001 | 0.42 (0.34, 0.52) | <0.001 |

| Age | 1.02 (1.01, 1.03) | <0.001 | 0.42 (0.34, 0.52) | <0.001 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | [reference] | [reference] | ||

| Male | 1.40 (1.16, 1.69) | <0.001 | 1.18 (0.97, 1.44) | 0.093 |

| TNM stage | ||||

| IIIA stage | [reference] | [reference] | ||

| IIIB stage | 1.16 (0.99, 1.36) | 0.064 | 1.28 (1.09, 1.52) | 0.003 |

| IIIC stage | 1.37 (1.09, 1.73) | 0.008 | 1.48 (1.16, 1.88) | 0.001 |

| Histology | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | [reference] | [reference] | ||

| Epidermoid | 1.45 (1.24, 1.70) | <0.001 | 1.29 (1.09, 1.53) | 0.003 |

| Others | 1.49 (1.13, 1.95) | 0.004 | 1.33 (1.01, 1.76) | 0.040 |

| Cardiovascular comorbidity | 1.22 (1.05, 1.41) | 0.010 | 1.04 (0.89, 1.22) | 0.639 |

| Respiratory comorbidity | 1.22 (1.04, 1.42) | 0.012 | 1.10 (0.93, 1.29) | 0.260 |

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p Value | HR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Immunotherapy | 0.51 (0.44, 0.59) | <0.001 | 0.48 (0.41, 0.57) | <0.001 |

| Age | 1.01 (1.00, 1.01) | 0.049 | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 0.786 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | [reference] | [reference] | ||

| Male | 1.21 (1.04, 1.41) | 0.013 | 1.14 (0.97, 1.34) | 0.118 |

| TNM stage | ||||

| IIIA stage | [reference] | [reference] | ||

| IIIB stage | 1.27 (1.11, 1.46) | <0.001 | 1.35 (1.17, 1.55) | <0.001 |

| IIIC stage | 1.40 (1.14, 1.72) | 0.001 | 1.51 (1.22, 1.86) | <0.001 |

| Histology | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | [reference] | [reference] | ||

| Epidermoid | 1.17 (1.03, 1.34) | 0.018 | 1.08 (0.94, 1.25) | 0.270 |

| Others | 1.20 (0.94, 1.52) | 0.140 | 1.10 (0.86, 1.40) | 0.443 |

| Cardiovascular comorbidity | 1.20 (1.05, 1.36) | 0.005 | 1.14 (0.99, 1.30) | 0.058 |

| Respiratory comorbidity | 1.22 (1.07, 1.39) | 0.003 | 1.19 (1.03, 1.36) | 0.015 |

| Type of Toxicity | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Pneumonitis | 24 (6.15) |

| Esophagitis | 18 (4.6) |

| Intestinal | 4 (1) |

| Hepatitis | 4 (1) |

| Cutaneous | 3 (0.7) |

| Thyroiditis | 3 (0.7) |

| Nephritis | 2 (0.5) |

| Cardiac | 1 (0.25) |

| Neuropathy | 1 (0.25) |

| Hematologic | 1 (0.25) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sosa-Fajardo, P.; Martín-Martín, M.; Luna-Tirado, J.; López-Guerra, J.L.; Gomis-Sellés, E.; López-Mata, M.; Valtueña-Peydró, G.; Santos-Rodríguez, M.; Álvarez-González, A.-M.; Potdevin-Stein, G.; et al. Stage III NSCLC Treatment Patterns in Spain: A Population-Based Study of the GOECP-SEOR. Cancers 2025, 17, 3807. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233807

Sosa-Fajardo P, Martín-Martín M, Luna-Tirado J, López-Guerra JL, Gomis-Sellés E, López-Mata M, Valtueña-Peydró G, Santos-Rodríguez M, Álvarez-González A-M, Potdevin-Stein G, et al. Stage III NSCLC Treatment Patterns in Spain: A Population-Based Study of the GOECP-SEOR. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3807. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233807

Chicago/Turabian StyleSosa-Fajardo, Paloma, Margarita Martín-Martín, Javier Luna-Tirado, José Luis López-Guerra, Elías Gomis-Sellés, Miriam López-Mata, Germán Valtueña-Peydró, Marina Santos-Rodríguez, Ana-María Álvarez-González, Guillermo Potdevin-Stein, and et al. 2025. "Stage III NSCLC Treatment Patterns in Spain: A Population-Based Study of the GOECP-SEOR" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3807. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233807

APA StyleSosa-Fajardo, P., Martín-Martín, M., Luna-Tirado, J., López-Guerra, J. L., Gomis-Sellés, E., López-Mata, M., Valtueña-Peydró, G., Santos-Rodríguez, M., Álvarez-González, A.-M., Potdevin-Stein, G., Martín-Barrientos, P., Kannemann, A., Farré-Bernadó, N., González-Portillo, E., Manso-Lema, A., Rodríguez-Roldán, M., González-Ruiz, M.-Á., Wals-Zurita, A., Linares-Mesa, N.-A., ... Couñago, F., on behalf of the GOECP Group. (2025). Stage III NSCLC Treatment Patterns in Spain: A Population-Based Study of the GOECP-SEOR. Cancers, 17(23), 3807. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233807