MicroRNA Profiling Identifies Diagnostic and Prognostic Markers in Pediatric Sarcoma

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

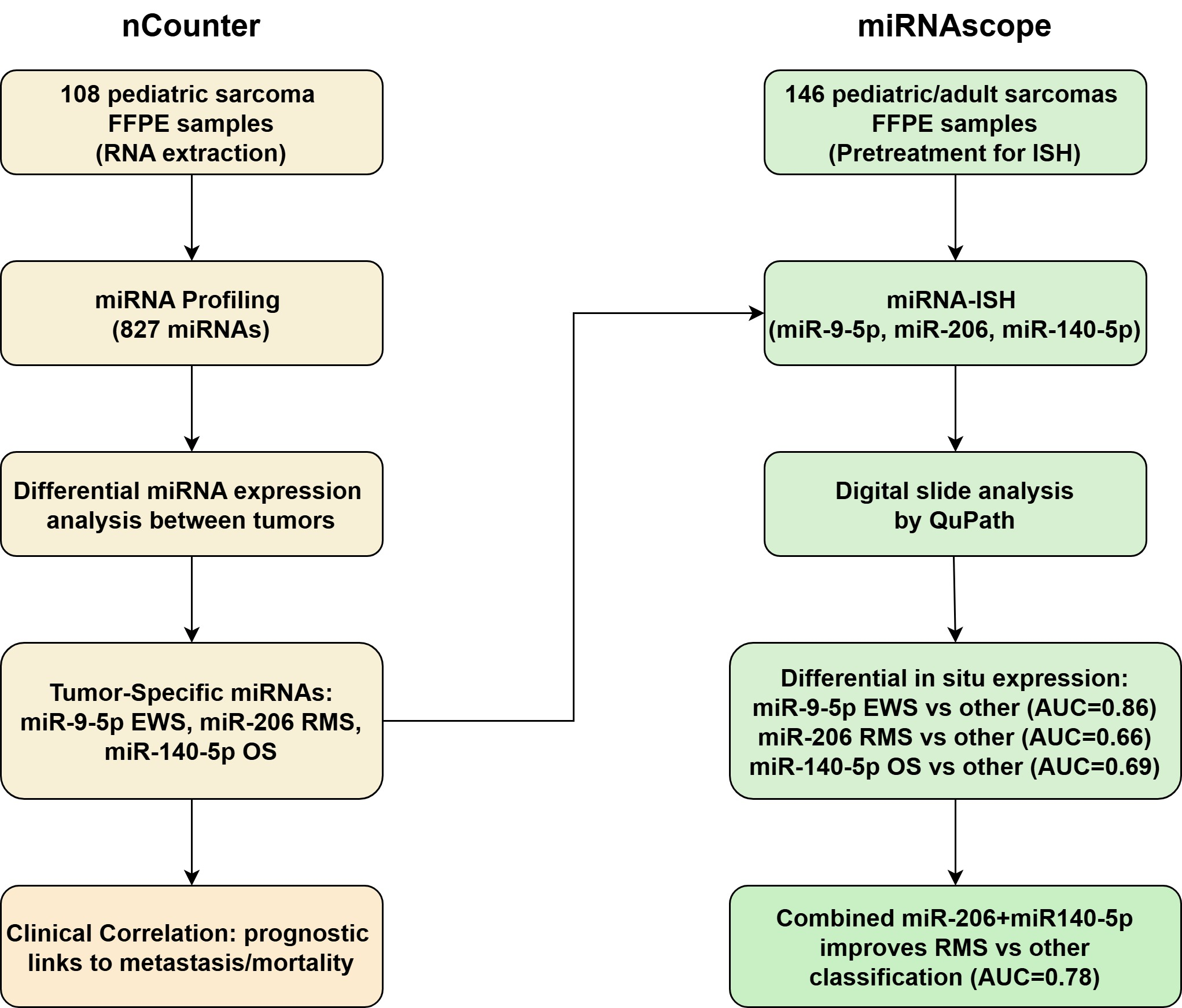

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Materials

2.2. NanoString nCounter miRNA Profiling

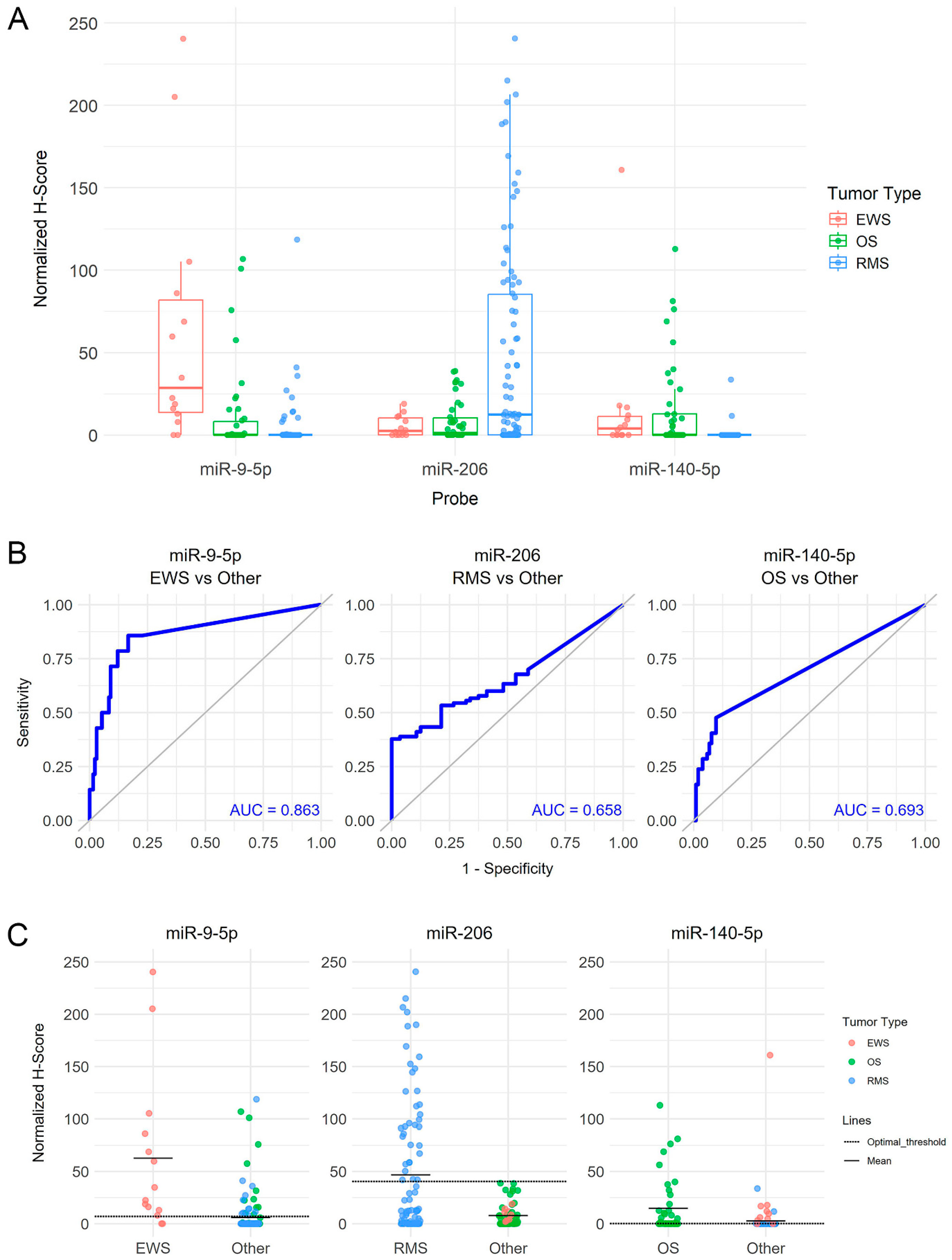

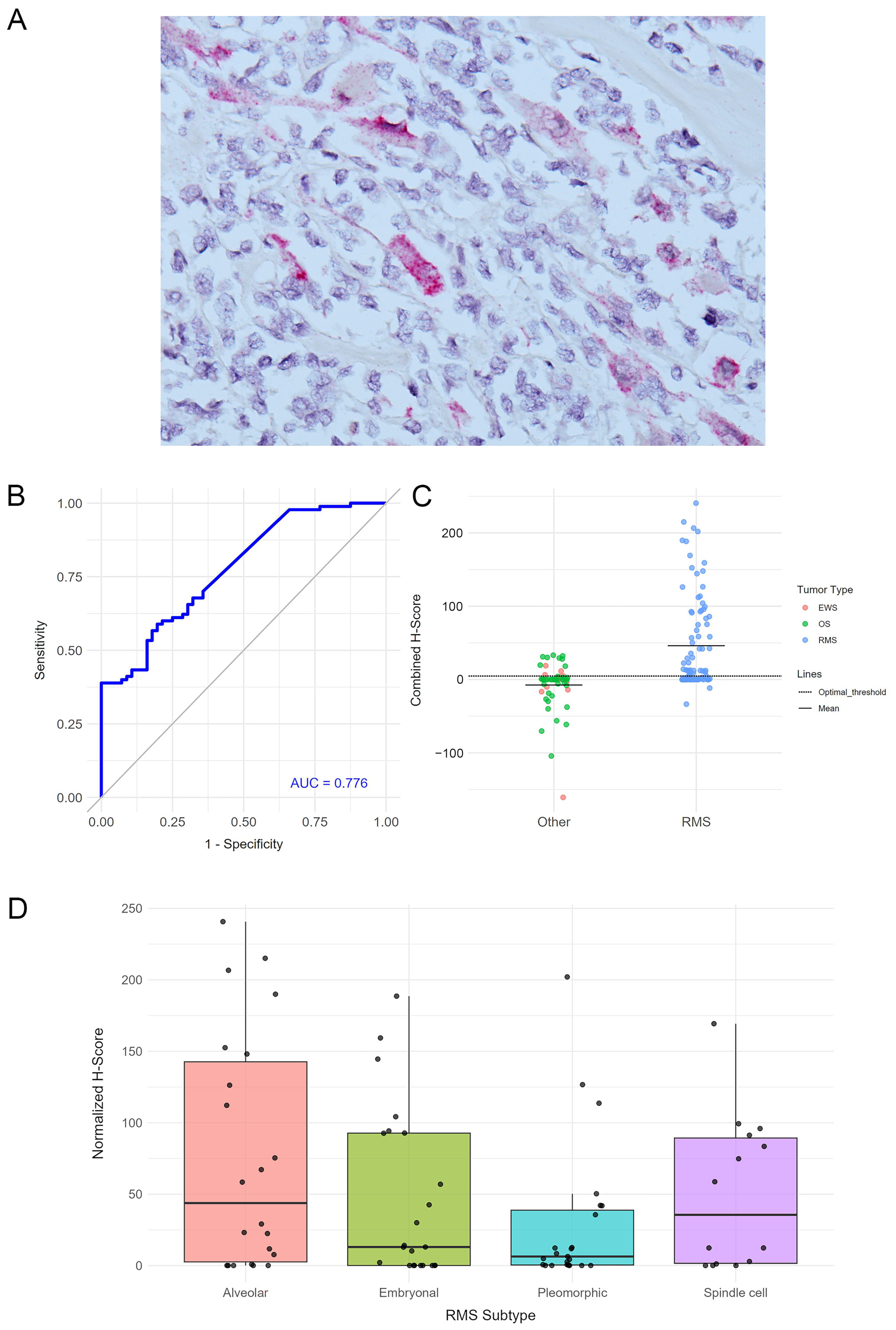

2.3. MicroRNA-Scope

2.4. QuPath Quantification

2.5. Statistical Analysis

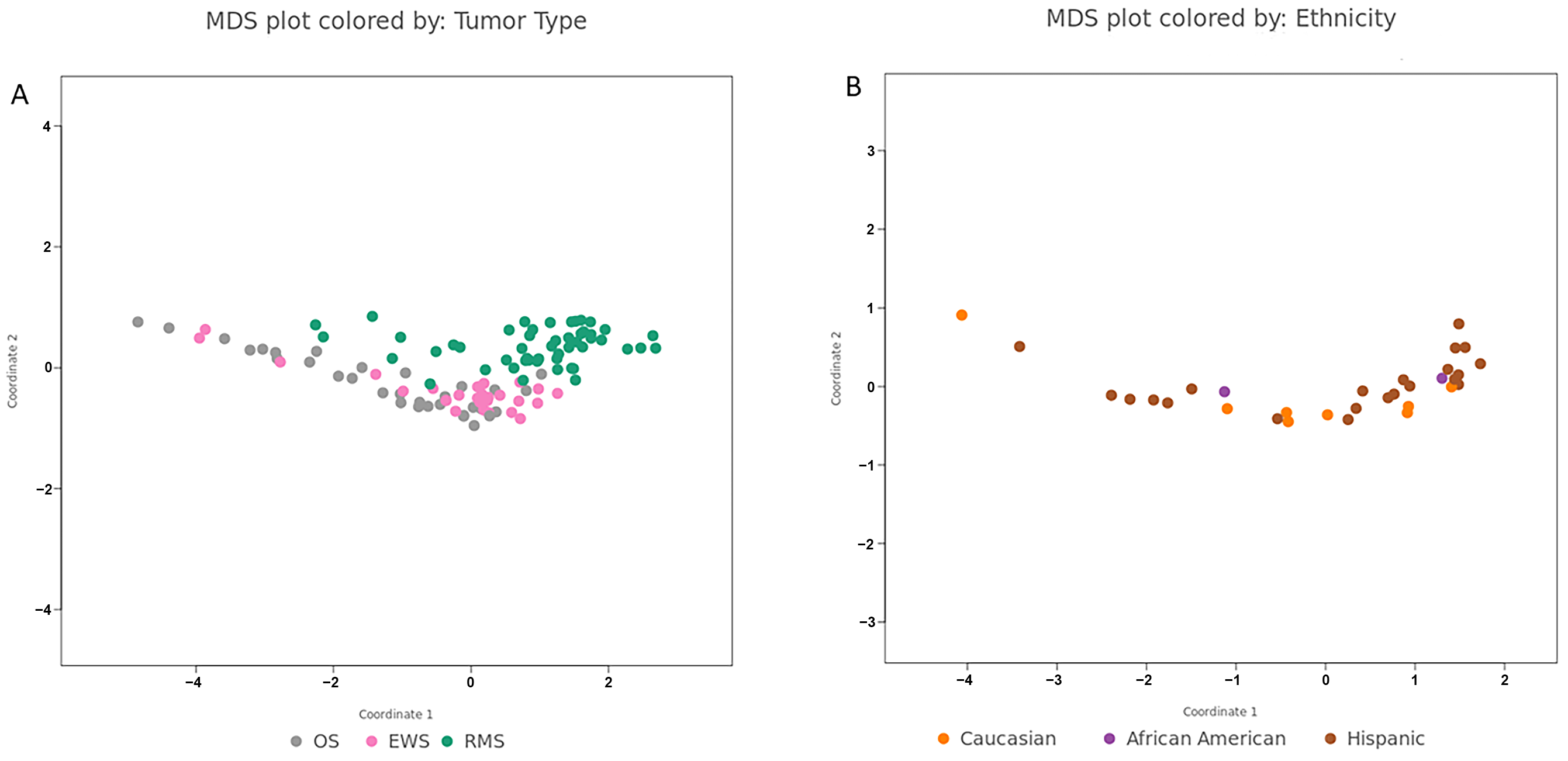

3. Results

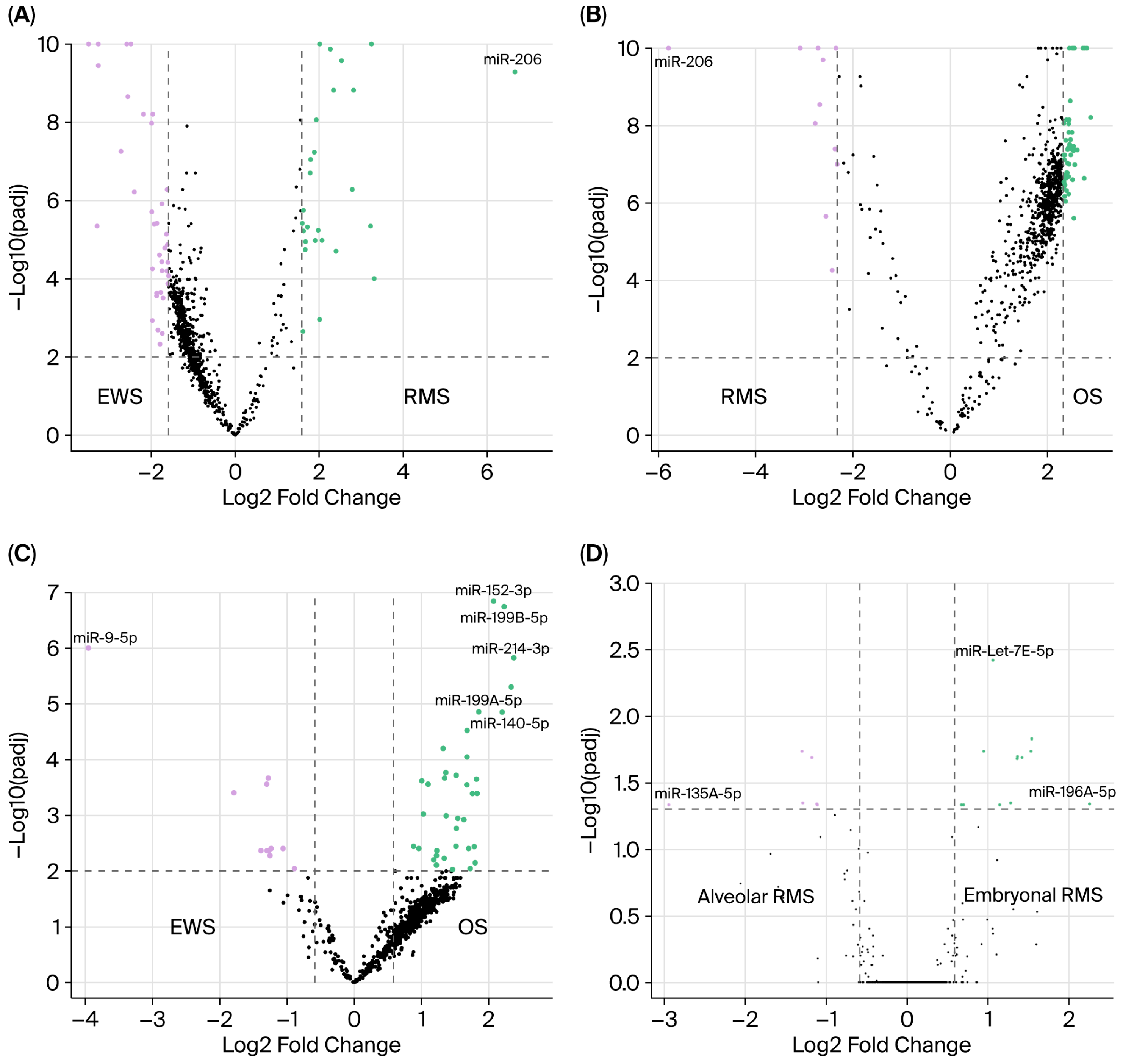

3.1. miRNA Expression in Rhabdomyosarcoma

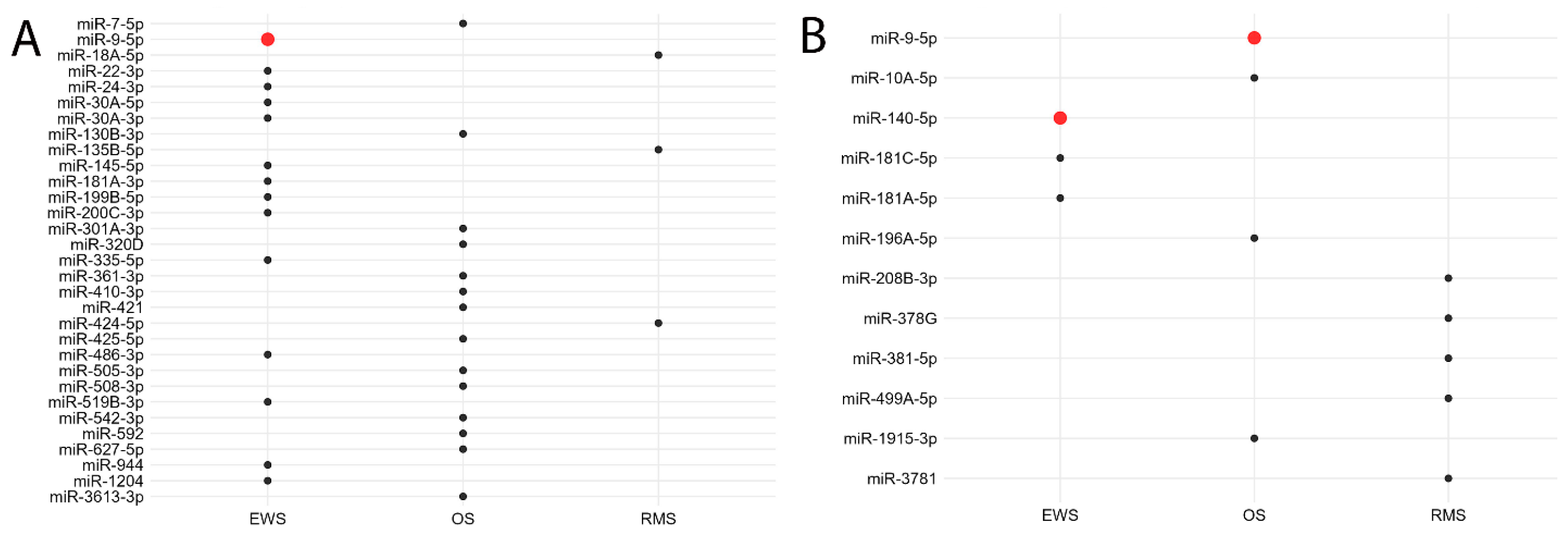

3.2. miRNA Expression in Ewing’s Sarcoma and Osteosarcoma

3.3. miRNA Expression and Patients’ Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bushati, N.; Cohen, S.M. microRNA functions. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2007, 23, 175–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassandro, G.; Ciaccia, L.; Amoruso, A.; Palladino, V.; Palmieri, V.V.; Giordano, P. Focus on MicroRNAs as Biomarker in Pediatric Diseases. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2021, 27, 826–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hata, A.; Lieberman, J. Dysregulation of microRNA biogenesis and gene silencing in cancer. Sci. Signal. 2015, 8, re3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorio, M.V.; Croce, C.M. MicroRNA dysregulation in cancer: Diagnostics, monitoring and therapeutics. A comprehensive review. EMBO Mol. Med. 2012, 4, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Getz, G.; Miska, E.A.; Alvarez-Saavedra, E.; Lamb, J.; Peck, D.; Sweet-Cordero, A.; Ebert, B.L.; Mak, R.H.; Ferrando, A.A.; et al. MicroRNA expression profiles classify human cancers. Nature 2005, 435, 834–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliminejad, K.; Khorram Khorshid, H.R.; Soleymani Fard, S.; Ghaffari, S.H. An overview of microRNAs: Biology, functions, therapeutics, and analysis methods. J. Cell Physiol. 2019, 234, 5451–5465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.S.; Johansson, P.; Chen, Q.R.; Song, Y.K.; Durinck, S.; Wen, X.; Cheuk, A.T.; Smith, M.A.; Houghton, P.; Morton, C.; et al. microRNA profiling identifies cancer-specific and prognostic signatures in pediatric malignancies. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 5560–5568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossland, R.E.; Macdonald, J.; Wang, X.N. Assessing MicroRNA Profiles from Low Concentration Extracellular Vesicle RNA Utilizing NanoString nCounter Technology. Methods Mol. Biol. 2024, 2822, 101–123. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Flanagan, J.; Su, N.; Wang, L.C.; Bui, S.; Nielson, A.; Wu, X.; Vo, H.T.; Ma, X.J.; Luo, Y. RNAscope: A novel in situ RNA analysis platform for formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues. J. Mol. Diagn. 2012, 14, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Golovnina, K.; Chen, Z.X.; Lee, H.N.; Negron, Y.L.; Sultana, H.; Oliver, B.; Harbison, S.T. Comparison of normalization and differential expression analyses using RNA-Seq data from 726 individual Drosophila melanogaster. BMC Genom. 2016, 17, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, M.E.; Phipson, B.; Wu, D.; Hu, Y.; Law, C.W.; Shi, W.; Smyth, G.K. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig, C. Cran-Package Fpc. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/fpc/index.html (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- Ru, Y.; Kechris, K.J.; Tabakoff, B.; Hoffman, P.; Radcliffe, R.A.; Bowler, R.; Mahaffey, S.; Rossi, S.; Calin, G.A.; Bemis, L.; et al. The multiMiR R package and database: Integration of microRNA-target interactions along with their disease and drug associations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, e133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, R.; Bernhart, S.H.; Zu Siederdissen, C.H.; Tafer, H.; Flamm, C.; Stadler, P.F.; Hofacker, I.L. ViennaRNA Package 2.0. Algorithms Mol. Biol. 2011, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankhead, P.; Loughrey, M.B.; Fernández, J.A.; Dombrowski, Y.; McArt, D.G.; Dunne, P.D.; McQuaid, S.; Gray, R.T.; Murray, L.J.; Coleman, H.G.; et al. QuPath: Open source software for digital pathology image analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 16878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, PBC, Boston. 2020. Available online: http://www.rstudio.com (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.D.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rota, R.; Ciarapica, R.; Giordano, A.; Miele, L.; Locatelli, F. MicroRNAs in rhabdomyosarcoma: Pathogenetic implications and translational potentiality. Mol. Cancer 2011, 10, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronez, L.C.; Fedatto, P.F.; Correa, C.A.P.; Lira, R.C.P.; Baroni, M.; da Silva, K.R.; Santos, P.; Antonio, D.S.M.; Queiroz, R.P.S.; Antonini, S.R.R.; et al. MicroRNA expression profile predicts prognosis of pediatric adrenocortical tumors. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2022, 69, e29553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyachi, M.; Tsuchiya, K.; Yoshida, H.; Yagyu, S.; Kikuchi, K.; Misawa, A.; Iehara, T.; Hosoi, H. Circulating muscle-specific microRNA, miR-206, as a potential diagnostic marker for rhabdomyosarcoma. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 400, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Missiaglia, E.; Shepherd, C.J.; Patel, S.; Thway, K.; Pierron, G.; Pritchard-Jones, K.; Renard, M.; Sciot, R.; Rao, P.; Oberlin, O.; et al. MicroRNA-206 expression levels correlate with clinical behaviour of rhabdomyosarcomas. Br. J. Cancer 2010, 102, 1769–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parafioriti, A.; Bason, C.; Armiraglio, E.; Calciano, L.; Daolio, P.A.; Berardocco, M.; Di Bernardo, A.; Colosimo, A.; Luksch, R.; Berardi, A.C. Ewing’s Sarcoma: An Analysis of miRNA Expression Profiles and Target Genes in Paraffin-Embedded Primary Tumor Tissue. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, C.; Liu, M.; Ding, Q.; Yang, F.; Xu, T. Upregulated miR-9-5p inhibits osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells under high glucose treatment. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2022, 40, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.; Singh, A.; Tippett, V.L.; Tattersall, L.; Shah, K.M.; Siachisumo, C.; Ward, N.J.; Thomas, P.; Carter, S.; Jeys, L.; et al. YBX1-interacting small RNAs and RUNX2 can be blocked in primary bone cancer using CADD522. J. Bone Oncol. 2023, 39, 100474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, R.; Cao, G.; Deng, Z.; Su, J.; Cai, L. miR-140-5p attenuates chemotherapeutic drug-induced cell death by regulating autophagy through inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate kinase 2 (IP3k2) in human osteosarcoma cells. Biosci. Rep. 2016, 36, e00392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.; Gu, J.; Ma, J.; Xu, R.; Wu, Q.; Meng, L.; Liu, H.; Li, L.; Xu, Y. GATA4-driven miR-206-3p signatures control orofacial bone development by regulating osteogenic and osteoclastic activity. Theranostics 2021, 11, 8379–8395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yao, C.; Li, H.; Wang, G.; He, X. Serum levels of microRNA-133b and microRNA-206 expression predict prognosis in patients with osteosarcoma. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2014, 7, 4194–4203. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Zhao, G.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Ding, Y.; Xu, N. MiR-199b-5p promotes malignant progression of osteosarcoma by regulating HER2. J. Buon 2018, 23, 1816–1824. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, H.; Miao, M.; Wang, Z. miR-214-3p promotes the proliferation, migration and invasion of osteosarcoma cells by targeting CADM1. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 16, 2620–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.M.; Piao, X.M.; Byun, Y.J.; Song, S.J.; Kim, S.K.; Moon, S.K.; Choi, Y.H.; Kang, H.W.; Kim, W.T.; Kim, Y.J.; et al. Study on the use of Nanostring nCounter to analyze RNA extracted from formalin-fixed-paraffin-embedded and fresh frozen bladder cancer tissues. Cancer Genet. 2022, 268–269, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chilimoniuk, J.; Erol, A.; Rödiger, S.; Burdukiewicz, M. Challenges and opportunities in processing NanoString nCounter data. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2024, 23, 1951–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Tumor Type | Osteosarcoma | Ewing’s Sarcoma | Rhabdomyosarcoma |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| <10 | 5 | 8 | 37 |

| 10–18 | 27 | 18 | 13 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 17 | 15 | 22 |

| Female | 15 | 11 | 28 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 22 | 15 | 43 |

| African American | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Asian | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Caucasian | 8 | 10 | 6 |

| Metastasis | |||

| Primary | 15 | 14 | 24 |

| Metastasis | 17 | 12 | 26 |

| Outcome Status | |||

| Alive | 13 | 9 | 32 |

| Dead | 19 | 13 | 18 |

| RMS Versus EWS (≥3-Fold Change, Adjusted p < 0.01) | RMS Versus OS (≥5-Fold Change, Adjusted p < 0.01) | EWS Versus OS (≥1.5-Fold Change, Adjusted p < 0.01) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMS | EWS | RMS | OS | EWS | OS |

| miR-206 * | miR-29A-3P | miR-206 * | miR-140-5P * | miR-9-5P *† | miR-214-3P |

| miR-1-3P | miR-9-5P *† | miR-495-3P | miR-218-5P | miR-29B-3P | miR-193A-5P+miR-193B-5P |

| miR-483-3P | miR-221-3P | miR-376C-3P | miR-181A-3P | miR-29A-3P | miR-199B-5P |

| miR-133A-3P | miR-29B-3P | miR-382-5P | miR-1469 | miR-221-3P | miR-140-5P * |

| miR-433-3P | miR-196A-5P | miR-376A-3P | miR-140-3P | miR-376C-3P | miR-152-3P |

| miR-133B | miR-497-5P | miR-381-3P | miR-603 | miR-195-5P | miR-199A-5P |

| miR-381-3P | miR-181A-3P † | miR-136-5P | miR-522-3P | miR-376A-3P | miR-450B-5P |

| miR-483-5P | miR-195-5P | miR-133A-3P | miR-3190-3P | miR-20A-5P+miR-20B-5P | miR-199A-3P+miR-199B-3P |

| miR-503-5P | miR-592 | miR-1-3P | miR-551B-3P | miR-130A-3P | miR-548AR-5P |

| miR-495-3P | miR-222-3P | miR-127-3P | miR-1285-5P | miR-19B-3P | miR-579-3P |

| miR-323A-3P | miR-10B-5P | miR-660-5P | miR-147A | miR-106A-5P+miR-17-5p | miR-105-5P |

| miR-450A-5P | miR-221-5P | miR-1264 | miR-574-5P | ||

| miR-135A-5P | miR-1972 | miR-10A-5P | miR-31-5P | ||

| miR-432-5P | miR-490-3P | miR-548AR-5P | miR-218-5P | ||

| miR-299-5P | miR-491-5P | miR-193A-3P | miR-193A-3P | ||

| miR-431-5P | miR-873-5P | miR-3144-3P | miR-140-3P | ||

| miR-500A-5P+miR-501-5P | miR-1290 | miR-3192-5P | miR-1233-3P | ||

| miR-660-5P | miR-150-5P | miR-571 | miR-551B-3P | ||

| miR-376C-3P | miR-4284 | miR-604 | miR-146A-5P | ||

| miR-382-5P | miR-1285-5P | miR-515-3P | miR-574-3P | ||

| miR-409-3P | miR-181A-5P | miR-520A-5P | miR-708-5P | ||

| miR-335-5P | miR-630 | miR-152-3P | miR-519D-3P | ||

| miR-136-5P | miR-494-3P | miR-574-5P | miR-155-5P | ||

| miR-874-3P | miR-765 | miR-365A-3P+miR-365B-3P | |||

| miR-10A-5P | miR-1908-5P | miR-424-5P | |||

| miR-1200 | miR-4755-5P | miR-196B-5P | |||

| miR-1246 | miR-642A-5P | miR-450A-5P | |||

| miR-593-3P | miR-3615 | miR-28-5P | |||

| miR-651-5P | miR-219A-2-3P | miR-503-5P | |||

| miR-181C-5P | miR-1910-5P | miR-148A-3P | |||

| miR-127-3P | miR-890 | miR-28-3P | |||

| miR-345-3P | miR-516B-5P | miR-23B-3P | |||

| miR-505-3P | miR-589-5P | miR-455-5P | |||

| miR-573 | miR-24-3P | ||||

| miR-31-5P | miR-27B-3P | ||||

| miR-3928-3P | miR-21-5P | ||||

| miR-519B-5P+miR-519C-5P+miR-523-5P+miR-518E-5P+miR-522-5P+miR-519A-5P | |||||

| miR-556-3P | |||||

| miR-200C-3P | |||||

| miR-891B | |||||

| miR-579-3P | |||||

| miR-504-3P | |||||

| miR-566 | |||||

| miR-2053 | |||||

| miR-548J-3P | |||||

| Alveolar RMS | Embryonal RMS |

|---|---|

| miR-362-5P | LET-7E-5P |

| miR-532-5P | miR-455-3P |

| miR-135-5P | miR-214-3P |

| miR-660-5P | miR-10B-5P |

| miR-500A-5P+miR-501-5P | miR-455-5P |

| miR-323A-3P | miR-199A-5P |

| miR-99B-5P | |

| miR-196A-5P | |

| miR-218-5P | |

| miR-199A-3P+miR-199B-3P | |

| miR-130A-3P | |

| LET-7C-5P |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Flatt, T.G.; Yermakov, L.M.; Akilesh, S.; Chen, E.Y.; Gonzalez, E.; Parrales, A.; Zapata-Tarres, M.; Cardenas-Cardos, R.; Velasco-Hidalgo, L.; Corcuera-Delgado, C.; et al. MicroRNA Profiling Identifies Diagnostic and Prognostic Markers in Pediatric Sarcoma. Cancers 2025, 17, 3791. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233791

Flatt TG, Yermakov LM, Akilesh S, Chen EY, Gonzalez E, Parrales A, Zapata-Tarres M, Cardenas-Cardos R, Velasco-Hidalgo L, Corcuera-Delgado C, et al. MicroRNA Profiling Identifies Diagnostic and Prognostic Markers in Pediatric Sarcoma. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3791. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233791

Chicago/Turabian StyleFlatt, Terrie G., Leonid M. Yermakov, Shreeram Akilesh, Eleanor Y. Chen, Elizabeth Gonzalez, Alejandro Parrales, Marta Zapata-Tarres, Rocio Cardenas-Cardos, Liliana Velasco-Hidalgo, Celso Corcuera-Delgado, and et al. 2025. "MicroRNA Profiling Identifies Diagnostic and Prognostic Markers in Pediatric Sarcoma" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3791. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233791

APA StyleFlatt, T. G., Yermakov, L. M., Akilesh, S., Chen, E. Y., Gonzalez, E., Parrales, A., Zapata-Tarres, M., Cardenas-Cardos, R., Velasco-Hidalgo, L., Corcuera-Delgado, C., Rodriguez-Jurado, R., García-Rodríguez, L., Farooqi, M. S., & Ahmed, A. A. (2025). MicroRNA Profiling Identifies Diagnostic and Prognostic Markers in Pediatric Sarcoma. Cancers, 17(23), 3791. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233791