Examining Health-Related Quality of Life in Cancer Survivors: Cross-Sectional Associations with Comorbidities, Navigation Services Use, and Perceived Social Support

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Health-Related Quality of Life

2.2.2. Comorbidity Burden

2.2.3. Patient Navigation Utilization

2.2.4. Perceived Social Support

2.2.5. Covariates

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HRQoL | Health-related quality of life |

| FACT-G | Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—General |

| MSPSS | Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support |

References

- Puerto Torres-Cintrón, C.R.; Suárez Ramos, T.; Pagán Santana, Y.; Román Ruiz, Y.; Gierbolini Bermúdez, A.; Ortiz Ortiz, K.J. Cáncer en Puerto Rico, 2018–2022; Registro Central de Cáncer de Puerto Rico: San Juan, Puerto Rico, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.M. Epidemiology of Cancer. Clin. Chem. 2024, 70, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos-Moreno, A.; Verdery, A.M.; Mendes de Leon, C.F.; De Jesús-Monge, V.M.; Santos-Lozada, A.R. Aging and the Left Behind: Puerto Rico and Its Unconventional Rapid Aging. Gerontologist 2022, 62, 964–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firkins, J.; Hansen, L.; Driessnack, M.; Dieckmann, N. Quality of life in “chronic” cancer survivors: A meta-analysis. J. Cancer Surviv. Res. Pract. 2020, 14, 504–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, T.; Suzuki, K.; Tanaka, T.; Okayama, T.; Inoue, J.; Morishita, S.; Nakano, J. Global quality of life and mortality risk in patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Qual. Life Res. 2024, 33, 2631–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neris, R.R.; Nascimento, L.C.; Leite, A.C.A.B.; de Andrade Alvarenga, W.; Polita, N.B.; Zago, M.M.F. The experience of health-related quality of life in extended and permanent cancer survivors: A qualitative systematic review. Psycho-Oncology 2020, 29, 1474–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, S.H.; Park, B.W.; Noh, D.Y.; Nam, S.J.; Lee, E.S.; Lee, M.K.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, K.M.; Park, S.M.; Yun, Y.H. Health-related quality of life in disease-free survivors of breast cancer with the general population. Ann. Oncol. 2007, 18, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bottomley, A. The cancer patient and quality of life. Oncologist 2002, 7, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benzo, R.M.; Moreno, P.I.; Fox, R.S.; Silvera, C.A.; Walsh, E.A.; Yanez, B.; Balise, R.R.; Oswald, L.B.; Penedo, F.J. Comorbidity burden and health-related quality of life in men with advanced prostate cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2023, 31, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.W.; Reeve, B.B.; Bellizzi, K.M.; Harlan, L.C.; Klabunde, C.N.; Amsellem, M.; Bierman, A.S.; Hays, R.D. Cancer, comorbidities, and health-related quality of life of older adults. Health Care Financ. Rev. 2008, 29, 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, M.R.; Axelrod, D.; Guth, A.A.; Cleland, C.M.; Ryan, C.E.; Weaver, K.R.; Qiu, J.M.; Kleinman, R.; Scagliola, J.; Palamar, J.J.; et al. Comorbidities and Quality of Life among Breast Cancer Survivors: A Prospective Study. J. Pers. Med. 2015, 5, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Rodriguez, J.L.; O’Brien, K.M.; Nichols, H.B.; Hodgson, M.E.; Weinberg, C.R.; Sandler, D.P. Health-related quality of life outcomes among breast cancer survivors. Cancer 2021, 127, 1114–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, A.; Fransen, H.P.; Quaresma, M.; Raijmakers, N.; Versluis, M.A.J.; Rachet, B.; van Maaren, M.C.; Leyrat, C. Associations between treatments, comorbidities and multidimensional aspects of quality of life among patients with advanced cancer in the Netherlands—A 2017–2020 multicentre cross-sectional study. Qual. Life Res. 2023, 32, 3123–3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekels, A.; van de Poll-Franse, L.V.; Issa, D.E.; Hoogendoorn, M.; Nijziel, M.R.; Koster, A.; de Jong, C.N.; Achouiti, A.; Thielen, N.; Tick, L.W.; et al. Impact of comorbidity on health-related quality of life in newly diagnosed patients with lymphoma or multiple myeloma: Results from the PROFILES-registry. Ann. Hematol. 2024, 103, 5511–5525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, X.Q.; Sun, S.J.; Wei, S.A.; Fang, S.W.; Xu, L.F.; Xiao, J.; Lu, M.M. Socioeconomic Status Plays a Moderating Role in the Association Between Multimorbidity and Health-Related Quality of Life Among Cancer Patients. Inq. A. J. Med. Care Organ. Provis. Financ. 2024, 61, 469580241264187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Hines, R.B.; Zhu, J.; Nam, E.; Rovito, M.J. Racial and Ethnic Variations in Pre-Diagnosis Comorbidity Burden and Health-Related Quality of Life Among Older Women with Breast Cancer. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2024, 11, 1587–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, C.; Fortin, M.; van den Akker, M.; Mair, F.; Calderon-Larranaga, A.; Boland, F.; Wallace, E.; Jani, B.; Smith, S. Comorbidity versus multimorbidity: Why it matters. J. Multimorb. Comorbidity 2021, 11, 2633556521993993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daw, J. Contribution of Four Comorbid Conditions to Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Mortality Risk. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 52, S95–S102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertz, B.G.; Dunn-Henriksen, A.K.; Kroman, N.; Johansen, C.; Andersen, K.G.; Andersson, M.; Mathiesen, U.B.; Vibe-Petersen, J.; Dalton, S.O.; Envold Bidstrup, P. The effects of individually tailored nurse navigation for patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer: A randomized pilot study. Acta Oncol. 2017, 56, 1682–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, A.G.; Muñoz, E.; Long Parma, D.; Perez, A.; Santillan, A. Quality of life outcomes from a randomized controlled trial of patient navigation in Latina breast cancer survivors. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 7837–7848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, A.G.; Choi, B.Y.; Munoz, E.; Perez, A.; Gallion, K.J.; Moreno, P.I.; Penedo, F.J. Assessing the effect of patient navigator assistance for psychosocial support services on health-related quality of life in a randomized clinical trial in Latino breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer survivors. Cancer 2020, 126, 1112–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellizzi, K.M.; Fritzson, E.; Ligus, K.; Park, C.L. Social Support Buffers the Effect of Social Deprivation on Comorbidity Burden in Adults with Cancer. Ann. Behav. Med. A. Publ. Soc. Behav. Med. 2024, 58, 701–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, J.; Tang, Y.; Chen, C.; Yu, C.; Li, X.; Peng, L.; Zheng, D. The impact of life events on health-related quality of life in rural older adults: The moderating role of social support. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1587104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, L.; Viroj, J.; Glangkarn, S. The Influencing Factors of Family Function, Social Support and Impact on Quality of Life in Patients with Gastrointestinal Cancer. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. APJCP 2025, 26, 2137–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vespa, A.; Spatuzzi, R.; Fabbietti, P.; Di Rosa, M.; Bonfigli, A.R.; Corsonello, A.; Gattafoni, P.; Giulietti, M.V. Association between Sense of Loneliness and Quality of Life in Older Adults with Multimorbidity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cella, D.F.; Tulsky, D.S.; Gray, G.; Sarafian, B.; Linn, E.; Bonomi, A.; Silberman, M.; Yellen, S.B.; Winicour, P.; Brannon, J. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: Development and validation of the general measure. J. Clin. Oncol. 1993, 11, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearman, T.; Yanez, B.; Peipert, J.; Wortman, K.; Beaumont, J.; Cella, D. Ambulatory cancer and US general population reference values and cutoff scores for the functional assessment of cancer therapy. Cancer 2014, 120, 2902–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spigel, D.R.; Patel, J.D.; Reynolds, C.H.; Garon, E.B.; Hermann, R.C.; Govindan, R.; Olsen, M.R.; Winfree, K.B.; Chen, J.; Liu, J.; et al. Quality of life analyses from the randomized, open-label, phase III PointBreak study of pemetrexed-carboplatin-bevacizumab followed by maintenance pemetrexed-bevacizumab versus paclitaxel-carboplatin-bevacizumab followed by maintenance bevacizumab in patients with stage IIIB or IV nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2015, 10, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, V.J.; McMillan, S.; Pedro, E.; Tirado-Gomez, M.; Saligan, L.N. The Health related Quality of Life of Puerto Ricans during Cancer Treatments; A Pilot Study. Puerto Rico Health Sci. J. 2018, 37, 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, C.; Deng, L.; Karr, M.A.; Wen, Y.; Wang, Q.; Perimbeti, S.; Shapiro, C.L.; Han, X. Chronic comorbid conditions among adult cancer survivors in the United States: Results from the National Health Interview Survey, 2002–2018. Cancer 2022, 128, 828–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, Y.; Fagan, J.; Tie, Y.; Padilla, M. Is Patient Navigation Used by People with HIV Who Need It? An Assessment from the Medical Monitoring Project, 2015–2017. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2020, 34, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Villalobos, C.; Briede-Westermeyer, J.C.; Schilling-Norman, M.J.; Contreras-Espinoza, S. Multidimensional scale of perceived social support: Evidence of validity and reliability in a Chilean adaptation for older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levinsen, A.K.G.; Kjaer, T.K.; Thygesen, L.C.; Maltesen, T.; Jakobsen, E.; Gögenur, I.; Borre, M.; Christiansen, P.; Zachariae, R.; Christensen, P.; et al. Social inequality in cancer survivorship: Educational differences in health-related quality of life among 27,857 cancer survivors in Denmark. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 20150–20162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.S.; Davis, J.E.; Chen, L. Impact of Comorbidity on Symptoms and Quality of Life Among Patients Being Treated for Breast Cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2019, 42, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forjaz, M.J.; Rodriguez-Blazquez, C.; Ayala, A.; Rodriguez-Rodriguez, V.; de Pedro-Cuesta, J.; Garcia-Gutierrez, S.; Prados-Torres, A. Chronic conditions, disability, and quality of life in older adults with multimorbidity in Spain. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2015, 26, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, A.; Champion, V.L.; Von Ah, D. Comorbidity, cognitive dysfunction, physical functioning, and quality of life in older breast cancer survivors. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, P.I.; Ramirez, A.G.; San Miguel-Majors, S.L.; Castillo, L.; Fox, R.S.; Gallion, K.J.; Munoz, E.; Estabrook, R.; Perez, A.; Lad, T.; et al. Unmet supportive care needs in Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors: Prevalence and associations with patient-provider communication, satisfaction with cancer care, and symptom burden. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 1383–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammarco, A.; Konecny, L.M. Quality of life, social support, and uncertainty among Latina breast cancer survivors. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2008, 35, 844–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammarco, A.; Konecny, L.M. Quality of life, social support, and uncertainty among Latina and Caucasian breast cancer survivors: A comparative study. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2010, 37, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Figueroa, E.M.; Torres-Blasco, N.; Rosal, M.C.; Jiménez, J.C.; Castro-Rodríguez, W.P.; González-Lorenzo, M.; Vélez-Cortés, H.; Toro-Bahamonde, A.; Costas-Muñiz, R.; Armaiz-Peña, G.N.; et al. Brief Report: Hispanic Patients’ Trajectory of Cancer Symptom Burden, Depression, Anxiety, and Quality of Life. Nurs. Rep. 2021, 11, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Total (n = 643) | Not Poor HRQoL (n = 317) | Poor HRQoL (n = 326) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | 0.304 | |||

| <40 years | 63 (9.8%) | 32 (50.8%) | 31 (49.2%) | |

| 40–64 years | 356 (55.4%) | 166 (46.6%) | 190 (53.4%) | |

| ≥65 years | 224 (34.8%) | 119 (53.1%) | 105 (46.9%) | |

| Sex at birth | 0.514 | |||

| Female | 461 (71.7%) | 231 (50.1%) | 230 (49.9%) | |

| Male | 182 (28.3%) | 86 (47.3%) | 96 (52.7%) | |

| Residence area | 0.367 | |||

| Urban | 362 (56.3%) | 187 (51.7%) | 175 (48.3%) | |

| Suburban | 81 (12.6%) | 39 (48.2%) | 42 (51.8%) | |

| Rural | 200 (31.1%) | 91 (45.5%) | 109 (54.5%) | |

| Education | 0.053 | |||

| High school or less | 170 (26.4%) | 73 (42.9%) | 97 (57.1%) | |

| More than high school | 473 (73.6%) | 244 (51.6%) | 229 (48.4%) | |

| Marital status | 0.584 | |||

| Married/lives with partner | 347 (54.0%) | 171 (49.3%) | 176 (50.7%) | |

| Separated/widowed/divorced | 205 (31.9%) | 97 (47.3%) | 108 (52.7%) | |

| Single/never married | 91 (14.1%) | 49 (53.8%) | 42 (46.2%) | |

| Cancer stage | 0.006 | |||

| Localized | 408 (63.4%) | 220 (53.9%) | 188 (46.1%) | |

| Regional | 136 (21.2%) | 62 (45.6%) | 74 (54.4%) | |

| Distant | 77 (12.0%) | 26 (33.8%) | 51 (66.2%) | |

| Unknown | 22 (3.4%) | 9 (40.9%) | 13 (59.1%) | |

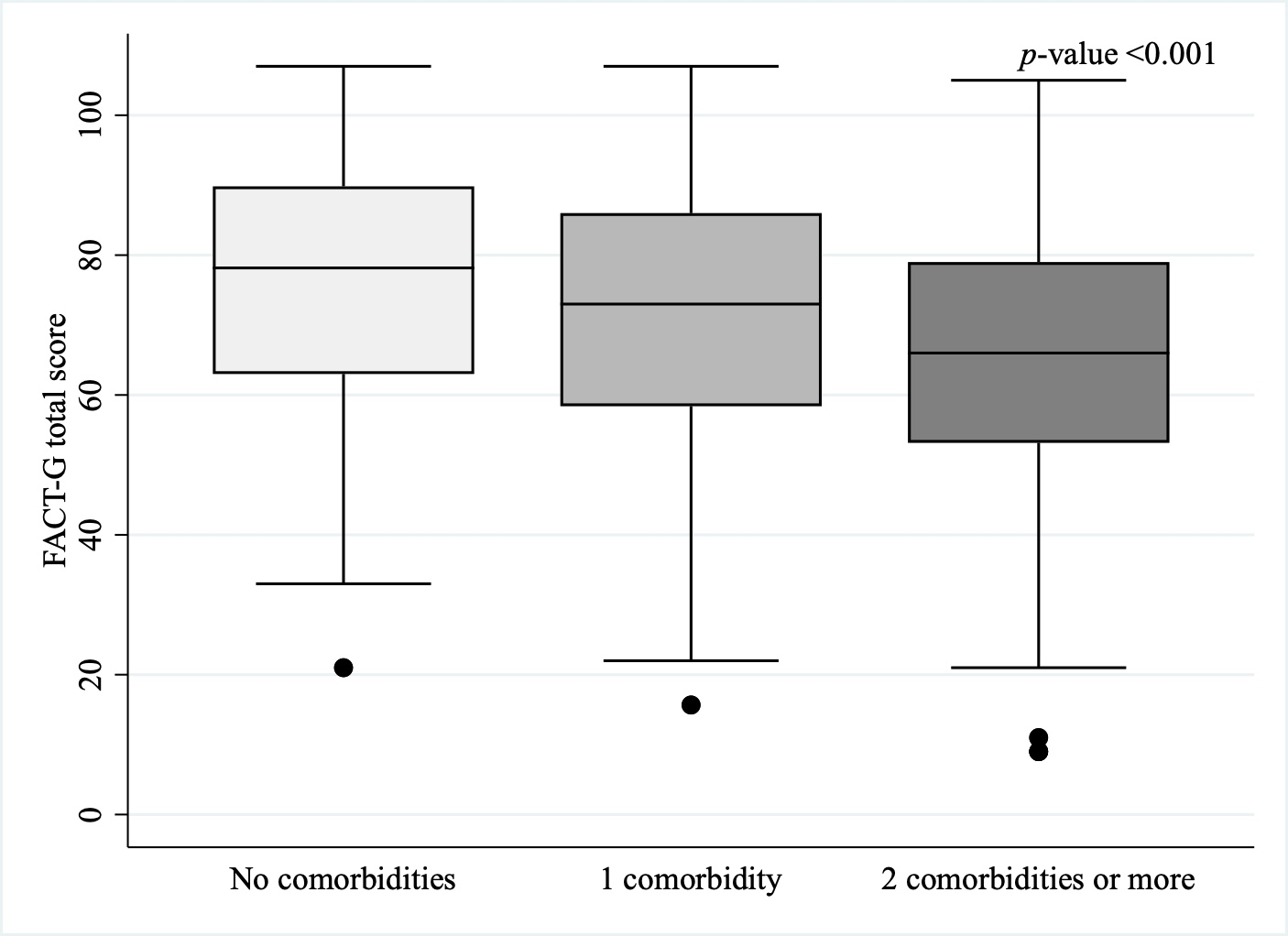

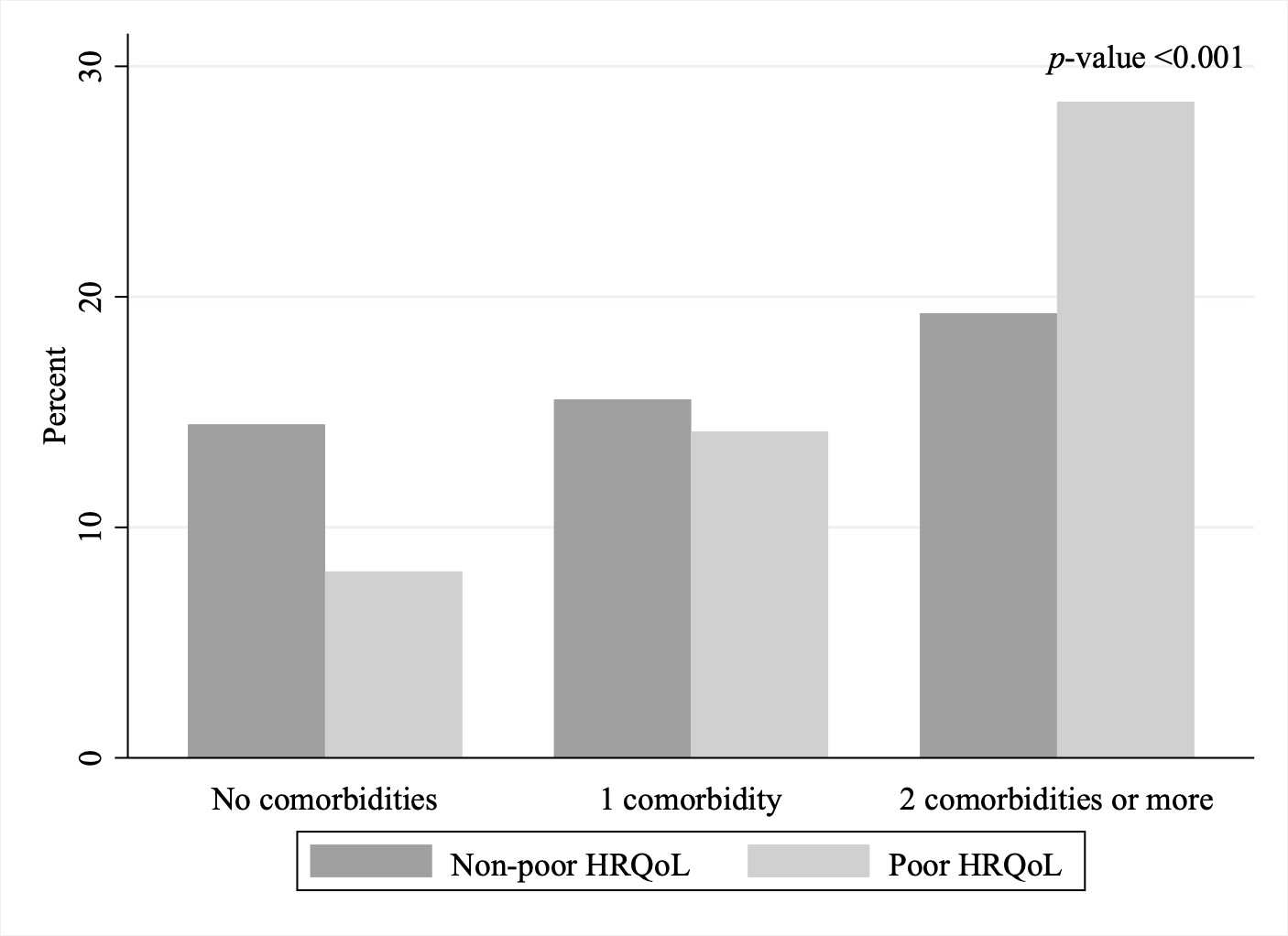

| Comorbidities | <0.001 | |||

| 0 | 145 (22.6%) | 93 (64.1%) | 52 (35.9%) | |

| 1 | 191 (29.7%) | 100 (52.4%) | 91 (47.6%) | |

| ≥2 | 307 (47.7%) | 124 (40.4%) | 183 (59.6%) | |

| Physical activity (last 30 days) | <0.001 | |||

| No | 429 (66.7%) | 178 (41.5%) | 251 (58.5%) | |

| Yes | 214 (33.3%) | 139 (64.9%) | 75 (35.1%) | |

| Smoking status | 0.509 | |||

| Non-smoker | 504 (78.4%) | 254 (50.4%) | 250 (49.6%) | |

| Past smoker | 110 (17.1%) | 51 (46.4%) | 59 (53.6%) | |

| Current smoker | 29 (4.5%) | 12 (41.4%) | 17 (58.6%) | |

| Alcohol (last 30 days) | 0.213 | |||

| No | 496 (77.1%) | 236 (47.6%) | 260 (52.4%) | |

| Moderate drinking | 56 (8.7%) | 33 (58.9%) | 23 (41.1%) | |

| Exceeded moderate drinking | 91 (14.2%) | 48 (52.7%) | 43 (47.3%) | |

| Current cancer treatment | 0.349 | |||

| No | 91 (14.2%) | 49 (53.8%) | 42 (46.2%) | |

| Yes | 552 (85.8%) | 268 (48.5%) | 284 (51.5%) | |

| Time since diagnosis | 0.264 | |||

| ≤5 years | 584 (90.8%) | 292 (50.0%) | 292 (50.0%) | |

| >5 years | 59 (9.2%) | 25 (42.4%) | 34 (57.6%) | |

| Multiple cancer diagnoses | 0.009 | |||

| No | 433 (67.3%) | 229 (52.9%) | 204 (47.1%) | |

| Yes | 210 (32.7%) | 88 (41.9%) | 122 (58.1%) | |

| Perceived social support mean score | 38.8 (8.9) | 42.5 (6.9) | 35.3 (9.3) | <0.001 |

| Patient Navigation | 0.006 | |||

| No | 464 (72.2%) | 213 (45.9%) | 251 (54.1%) | |

| Yes | 179 (27.8%) | 104 (58.1%) | 75 (41.9%) |

| Condition | Non-Poor HRQoL | Poor HRQoL | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ranking | n (%) * | Ranking | n (%) * | ||

| Hypertension | 1 | 134 (44.2) | 1 | 169 (55.8) | 0.013 |

| Diabetes | 2 | 61 (40.1) | 2 | 91 (59.9) | 0.009 |

| Depression | 5 | 32 (26.2) | 3 | 90 (73.8) | <0.001 |

| Arthritis | 3 | 56 (41.8) | 4 | 78 (58.2) | 0.048 |

| Asthma | 4 | 47 (37.9) | 5 | 77 (62.1) | 0.004 |

| Comorbidity Burden | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR * (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | 1.63 (1.05–2.53) | 1.85 (1.15–2.97) |

| 2 | 2.64 (1.75–3.97) | 2.95 (1.88–4.61) |

| Variable | No Comorbidities | 1 Comorbidity Adjusted OR (95% CI) * | ≥2 Comorbidities Adjusted OR (95% CI) * | p-Value for Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient navigation use | ||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.92 (1.09–3.38) | 3.33 (1.94–5.70) | 0.866 |

| Yes | 1.00 | 1.76 (0.64–4.83) | 2.65 (1.05–6.69) | |

| Perceived social support | ||||

| Low | 1.00 | 1.86 (0.88–3.97) | 3.38 (1.60–7.15) | 0.535 |

| High | 1.00 | 1.12 (0.54–2.33) | 2.24 (1.18–4.24) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

López-Vallejo, D.; Pérez, C.M.; González-Sepúlveda, L.; Soto-Salgado, M. Examining Health-Related Quality of Life in Cancer Survivors: Cross-Sectional Associations with Comorbidities, Navigation Services Use, and Perceived Social Support. Cancers 2025, 17, 3784. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233784

López-Vallejo D, Pérez CM, González-Sepúlveda L, Soto-Salgado M. Examining Health-Related Quality of Life in Cancer Survivors: Cross-Sectional Associations with Comorbidities, Navigation Services Use, and Perceived Social Support. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3784. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233784

Chicago/Turabian StyleLópez-Vallejo, Daniela, Cynthia M. Pérez, Lorena González-Sepúlveda, and Marievelisse Soto-Salgado. 2025. "Examining Health-Related Quality of Life in Cancer Survivors: Cross-Sectional Associations with Comorbidities, Navigation Services Use, and Perceived Social Support" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3784. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233784

APA StyleLópez-Vallejo, D., Pérez, C. M., González-Sepúlveda, L., & Soto-Salgado, M. (2025). Examining Health-Related Quality of Life in Cancer Survivors: Cross-Sectional Associations with Comorbidities, Navigation Services Use, and Perceived Social Support. Cancers, 17(23), 3784. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233784