Gut Microbiota Signatures Associate with Chemotherapy-Related Adverse Events in Breast Cancer Patients

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Population

2.2. Fecal Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

2.3. 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

2.4. Adverse Event Assessment

2.5. Statistical and Microbial Community Analysis

2.6. Differential Abundance and Association Analysis

2.7. Data Visualization

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

3.2. Chemotherapy-Related Adverse Event Profile

3.3. Gut Microbiota Alterations Associated with Chemotherapy-Induced Hematologic Toxicity

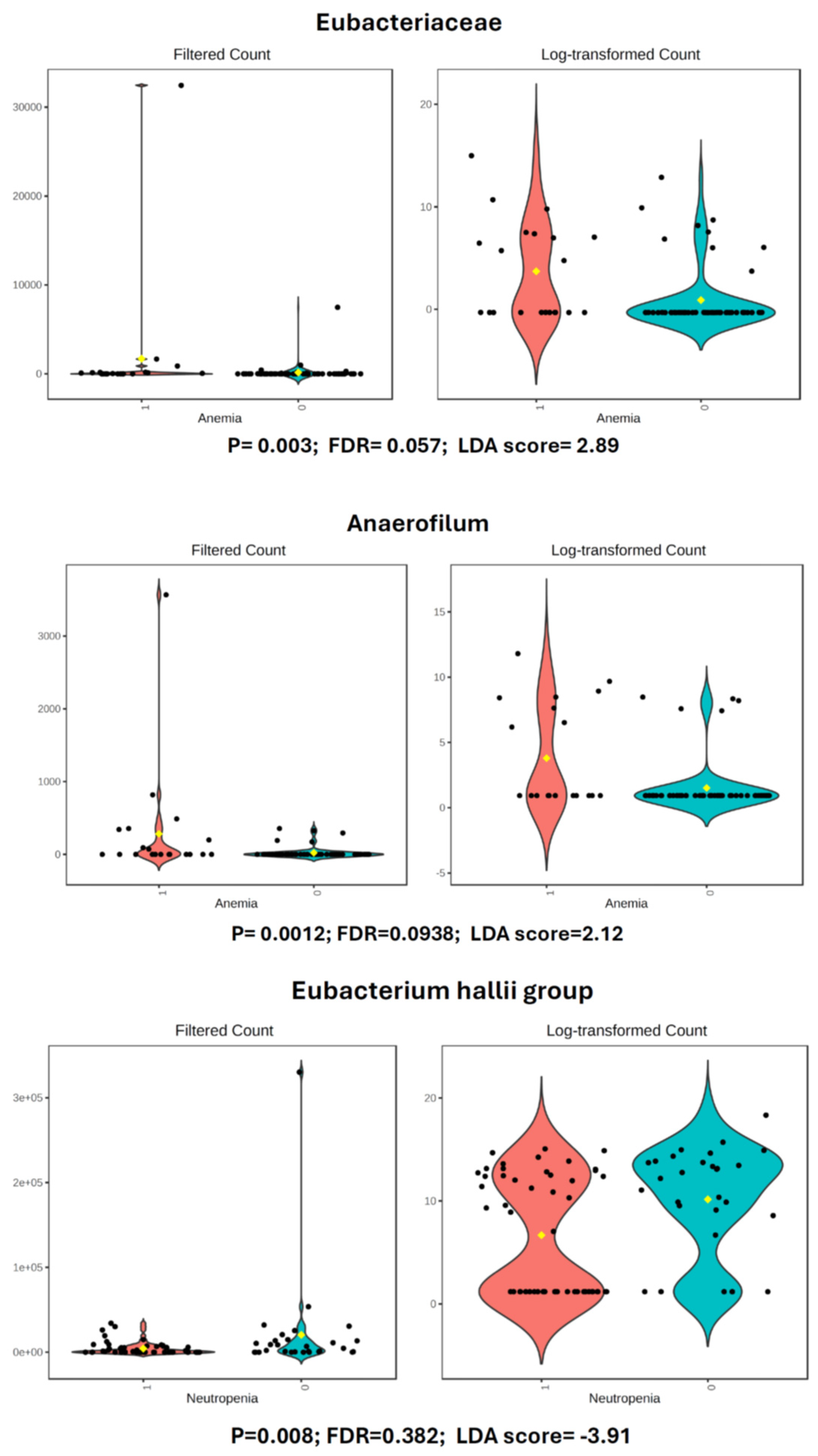

3.3.1. Anemia

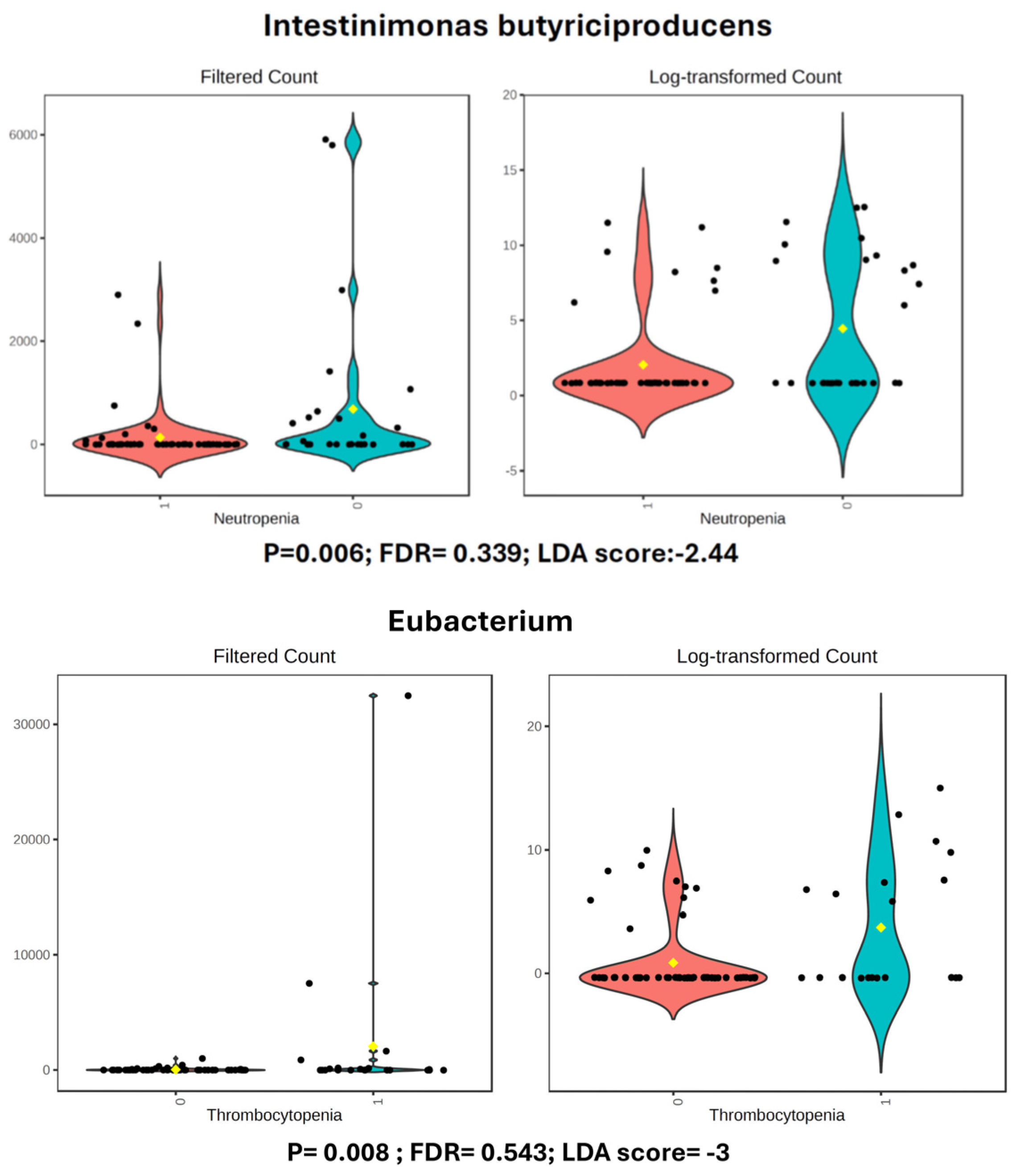

3.3.2. Neutropenia

3.3.3. Thrombocytopenia

3.4. Gut Microbiota Alterations Associated with Chemotherapy-Induced Hepatotoxicity

3.4.1. ALT (GPT) Elevation

3.4.2. AST (GOT) Elevation

3.5. Gut Microbiota Alterations Associated with Chemotherapy-Induced Gastrointestinal Toxicity

3.5.1. Nausea

3.5.2. Oral Mucositis

3.5.3. Diarrhea

3.6. Gut Microbiota Alterations Associated with Chemotherapy-Induced Neurological Toxicity

3.7. Gut Microbiota Alterations Associated with Chemotherapy-Induced Dermatologic Toxicity

3.7.1. Maculopapular Rash

3.7.2. Hand-Foot Syndrome

3.8. Gut Microbiota Alterations Associated with Chemotherapy-Induced Fatigue

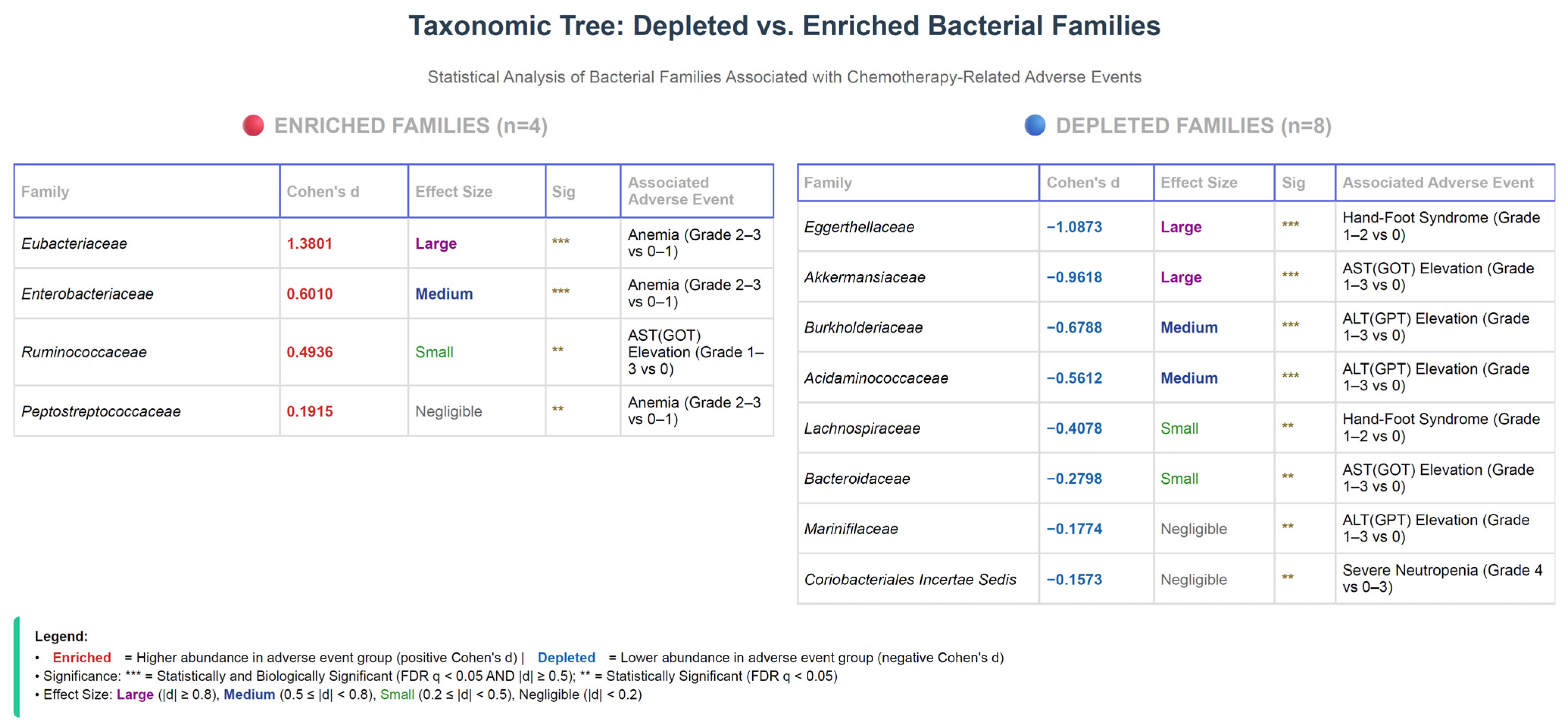

3.9. Summary of Bacterial Family Associations Across Adverse Events

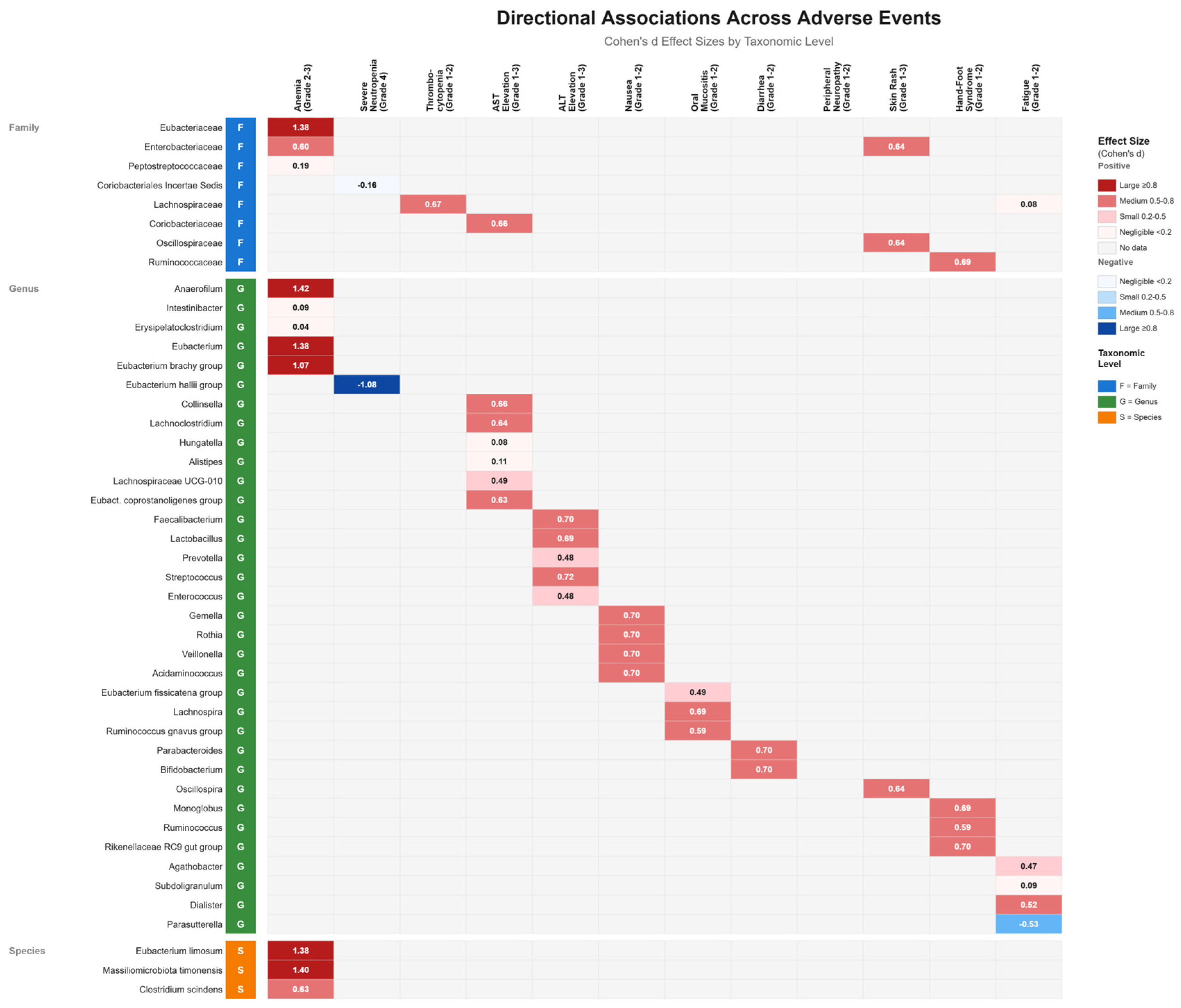

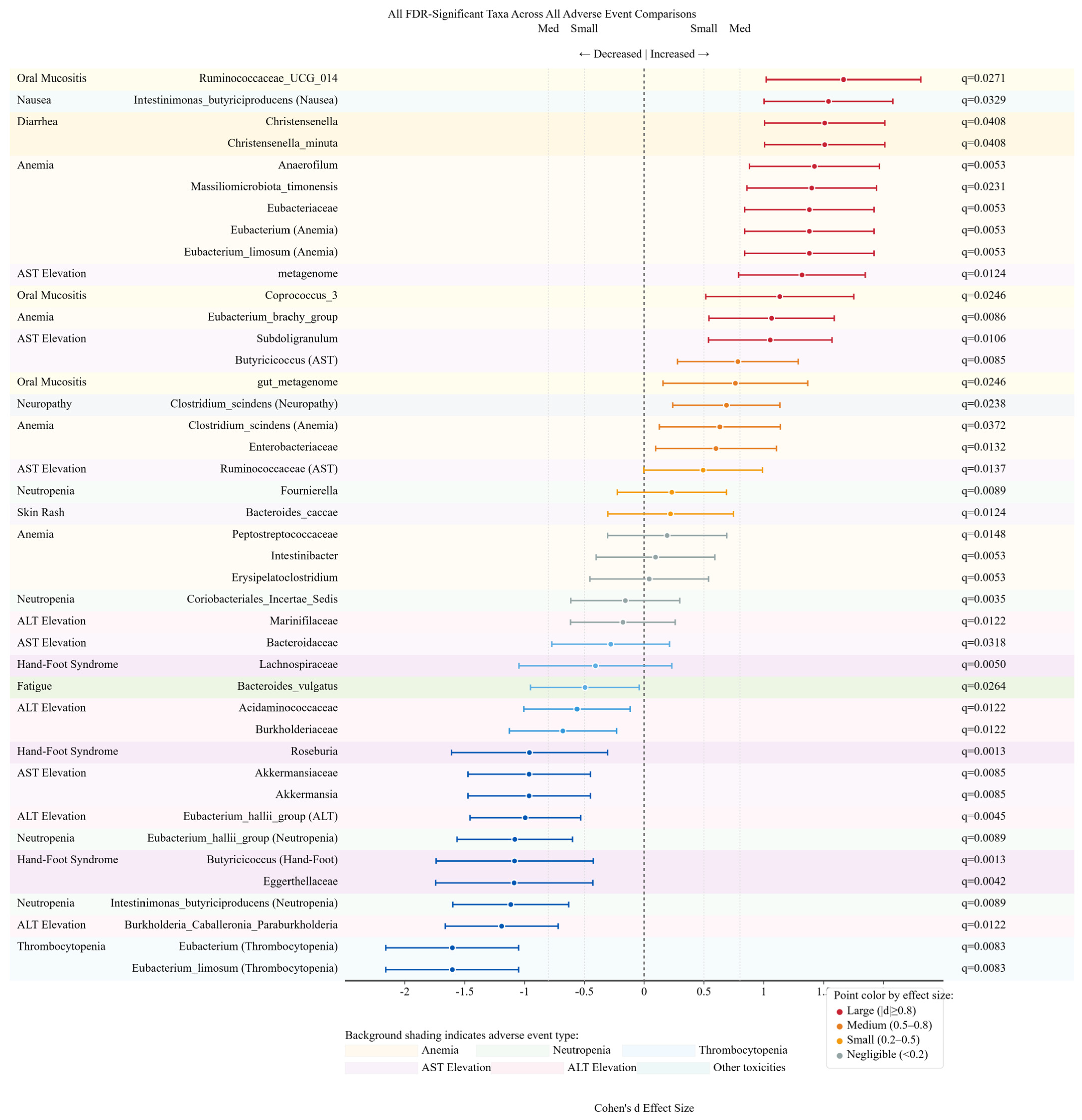

3.10. Directional Association Patterns Between Gut Microbiota and Adverse Events

3.11. Effect Size Distribution and Biomarker Potential

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALT | Alanine Aminotransferase |

| ANC | Absolute Neutrophil Count |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| AST | Aspartate Aminotransferase |

| BRCA | Breast Cancer gene |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CTCAE | Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| GOT | Glutamic-Oxaloacetic Transaminase |

| GPT | Glutamic-Pyruvic Transaminase |

| HER2 | Human Epidermal growth factor Receptor 2 |

| HFS | Hand-Foot Syndrome |

| HR | Hormone Receptor |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| LDA | Linear Discriminant Analysis |

| LEfSe | Linear discriminant analysis Effect Size |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MMH | MacKay Memorial Hospital |

| NCBI | National Center for Biotechnology Information |

| NCDB | National Cancer Database |

| NSTC | National Science and Technology Council |

| OTU | Operational Taxonomic Unit |

| pCR | Pathologic Complete Response |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PCoA | Principal Coordinates Analysis |

| PERMANOVA | Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance |

| PSN | Peripheral Sensory Neuropathy |

| rRNA | Ribosomal Ribonucleic Acid |

| SCFAs | Short-Chain Fatty Acids |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| TDM-1 | Trastuzumab emtansine |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha |

| ULN | Upper Limit of Normal |

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebert, J.M.; Lester, R.; Powell, E.; Seal, M.; McCarthy, J. Advances in the systemic treatment of triple-negative breast cancer. Curr. Oncol. 2018, 25 (Suppl. S1), S142–S150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeidman, M.; Alberty-Oller, J.J.; Ru, M.; Pisapati, K.V.; Moshier, E.; Ahn, S.; Mazumdar, M.; Port, E.; Schmidt, H. Use of neoadjuvant versus adjuvant chemotherapy for hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: A National Cancer Database (NCDB) study. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2020, 184, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, B.L.; Day, C.N.; Hoskin, T.L.; Habermann, E.B.; Boughey, J.C. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Use in Breast Cancer is Greatest in Excellent Responders: Triple-Negative and HER2+ Subtypes. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 25, 2241–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubovszky, G.; Horvath, Z. Recent Advances in the Neoadjuvant Treatment of Breast Cancer. J. Breast Cancer 2017, 20, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moo, T.A.; Sanford, R.; Dang, C.; Morrow, M. Overview of Breast Cancer Therapy. PET Clin. 2018, 13, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorn, C.F.; Oshiro, C.; Marsh, S.; Hernandez-Boussard, T.; McLeod, H.; Klein, T.E.; Altman, R.B. Doxorubicin pathways: Pharmacodynamics and adverse effects. Pharmacogenet Genom. 2011, 21, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarali, H.I.; Muchhala, K.H.; Jessup, D.K.; Cheatham, S. Chemotherapy induced gastrointestinal toxicities. Adv. Cancer Res. 2022, 155, 131–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrisse, S.; Derosa, L.; Iebba, V.; Ghiringhelli, F.; Vaz-Luis, I.; Kroemer, G.; Fidelle, M.; Christodoulidis, S.; Segata, N.; Thomas, A.M.; et al. Intestinal microbiota influences clinical outcome and side effects of early breast cancer treatment. Cell Death Differ. 2021, 28, 2778–2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugam, M.; Raes, J.; Pelletier, E.; Le Paslier, D.; Yamada, T.; Mende, D.R.; Fernandes, G.R.; Tap, J.; Bruls, T.; Batto, J.M.; et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature 2011, 473, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, M.F.; Reina-Perez, I.; Astorga, J.M.; Rodriguez-Carrillo, A.; Plaza-Diaz, J.; Fontana, L. Breast Cancer and Its Relationship with the Microbiota. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francescone, R.; Hou, V.; Grivennikov, S.I. Microbiome, inflammation, and cancer. Cancer J. 2014, 20, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwabe, R.F.; Jobin, C. The microbiome and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2013, 13, 800–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirbel, J.; Pyl, P.T.; Kartal, E.; Zych, K.; Kashani, A.; Milanese, A.; Fleck, J.S.; Voigt, A.Y.; Palleja, A.; Ponnudurai, R.; et al. Meta-analysis of fecal metagenomes reveals global microbial signatures that are specific for colorectal cancer. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Yang, Z.; Yu, J.; Wei, M. The interaction between gut microbiome and anti-tumor drug therapy. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2021, 11, 5812–5832. [Google Scholar]

- Klunemann, M.; Andrejev, S.; Blasche, S.; Mateus, A.; Phapale, P.; Devendran, S.; Vappiani, J.; Simon, B.; Scott, T.A.; Kafkia, E.; et al. Bioaccumulation of therapeutic drugs by human gut bacteria. Nature 2021, 597, 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Modica, M.; Gargari, G.; Regondi, V.; Bonizzi, A.; Arioli, S.; Belmonte, B.; De Cecco, L.; Fasano, E.; Bianchi, F.; Bertolotti, A.; et al. Gut Microbiota Condition the Therapeutic Efficacy of Trastuzumab in HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 2195–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Routy, B.; Le Chatelier, E.; Derosa, L.; Duong, C.P.M.; Alou, M.T.; Daillere, R.; Fluckiger, A.; Messaoudene, M.; Rauber, C.; Roberti, M.P.; et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science 2018, 359, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Dong, B.; Wu, W.; Wang, J.; Jin, H.; Chen, K.; Huang, K.; Huang, S.; Yao, Y. Metagenomic Analyses Reveal Distinct Gut Microbiota Signature for Predicting the Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Responsiveness in Breast Cancer Patients. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 865121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, A.; Bawaneh, A.; Velazquez, C.; Clear, K.Y.J.; Wilson, A.S.; Howard-McNatt, M.; Levine, E.A.; Levi-Polyachenko, N.; Yates-Alston, S.A.; Diggle, S.P.; et al. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Shifts Breast Tumor Microbiota Populations to Regulate Drug Responsiveness and the Development of Metastasis. Mol. Cancer Res. 2020, 18, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cray, P.; Sheahan, B.J.; Cortes, J.E.; Dekaney, C.M. Doxorubicin increases permeability of murine small intestinal epithelium and cultured T84 monolayers. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, S.M.; Tran, H.T.T.; Long, J.; Shrubsole, M.J.; Cai, H.; Yang, Y.; Cai, Q.; Tran, T.V.; Zheng, W.; Shu, X.O. Gut microbiome in association with chemotherapy-induced toxicities among patients with breast cancer. Cancer 2024, 130, 2014–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Alexander, S.G.; Martin, S. Gut microbiome homeostasis and the future of probiotics in cancer immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1114499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Gong, J.; Cottrill, M.; Yu, H.; de Lange, C.; Burton, J.; Topp, E. Evaluation of QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit for ecological studies of gut microbiota. J. Microbiol. Methods 2003, 54, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klindworth, A.; Pruesse, E.; Schweer, T.; Peplies, J.; Quast, C.; Horn, M.; Glockner, F.O. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeSantis, T.Z.; Hugenholtz, P.; Larsen, N.; Rojas, M.; Brodie, E.L.; Keller, K.; Huber, T.; Dalevi, D.; Hu, P.; Andersen, G.L. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 5069–5072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segata, N.; Izard, J.; Waldron, L.; Gevers, D.; Miropolsky, L.; Garrett, W.S.; Huttenhower, C. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grander, C.; Adolph, T.E.; Wieser, V.; Lowe, P.; Wrzosek, L.; Gyongyosi, B.; Ward, D.V.; Grabherr, F.; Gerner, R.R.; Pfister, A.; et al. Recovery of ethanol-induced Akkermansia muciniphila depletion ameliorates alcoholic liver disease. Gut 2018, 67, 891–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plovier, H.; Everard, A.; Druart, C.; Depommier, C.; Van Hul, M.; Geurts, L.; Chilloux, J.; Ottman, N.; Duparc, T.; Lichtenstein, L.; et al. A purified membrane protein from Akkermansia muciniphila or the pasteurized bacterium improves metabolism in obese and diabetic mice. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reunanen, J.; Kainulainen, V.; Huuskonen, L.; Ottman, N.; Belzer, C.; Huhtinen, H.; de Vos, W.M.; Satokari, R. Akkermansia muciniphila Adheres to Enterocytes and Strengthens the Integrity of the Epithelial Cell Layer. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 3655–3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depommier, C.; Everard, A.; Druart, C.; Plovier, H.; Van Hul, M.; Vieira-Silva, S.; Falony, G.; Raes, J.; Maiter, D.; Delzenne, N.M.; et al. Supplementation with Akkermansia muciniphila in overweight and obese human volunteers: A proof-of-concept exploratory study. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1096–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, N.R.; Lee, J.C.; Lee, H.Y.; Kim, M.S.; Whon, T.W.; Lee, M.S.; Bae, J.W. An increase in the Akkermansia spp. population induced by metformin treatment improves glucose homeostasis in diet-induced obese mice. Gut 2014, 63, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everard, A.; Belzer, C.; Geurts, L.; Ouwerkerk, J.P.; Druart, C.; Bindels, L.B.; Guiot, Y.; Derrien, M.; Muccioli, G.G.; Delzenne, N.M.; et al. Cross-talk between Akkermansia muciniphila and intestinal epithelium controls diet-induced obesity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 9066–9071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, N.; Tan, H.Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, C.; Feng, Y. Function of Akkermansia muciniphila in Obesity: Interactions With Lipid Metabolism, Immune Response and Gut Systems. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Li, Q.; Cheng, L.; Buch, H.; Zhang, F. Akkermansia muciniphila is a promising probiotic. Microb. Biotechnol. 2019, 12, 1109–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, S.H.; Louis, P.; Flint, H.J. Lactate-utilizing bacteria, isolated from human feces, that produce butyrate as a major fermentation product. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 5810–5817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miquel, S.; Martin, R.; Rossi, O.; Bermudez-Humaran, L.G.; Chatel, J.M.; Sokol, H.; Thomas, M.; Wells, J.M.; Langella, P. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and human intestinal health. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2013, 16, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorente, C.; Jepsen, P.; Inamine, T.; Wang, L.; Bluemel, S.; Wang, H.J.; Loomba, R.; Bajaj, J.S.; Schubert, M.L.; Sikaroodi, M.; et al. Gastric acid suppression promotes alcoholic liver disease by inducing overgrowth of intestinal Enterococcus. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Clinica T stage | |

| cT1 | 20 (24.7%) |

| cT2 | 48 (59.3%) |

| cT3 | 9 (11.1%) |

| cT4 | 4 (4.9%) |

| Clinical N stage | |

| cN0 | 59 (72.8%) |

| cN+ | 22 (27.2%) |

| Clinical Stage | |

| IA | 20 (24.7%) |

| IIA | 33 (40.7%) |

| IIB | 15 (18.5%) |

| IIIA | 4 (4.9%) |

| IIIB | 3 (3.7%) |

| IIIC | 1 (1.2%) |

| IV | 5 (6.2%) |

| Molecular Subgroup | |

| Luminal A | 16 (19.8%) |

| Luminal B | 28 (34.6%) |

| Luminal Her2 | 12 (14.8%) |

| Her2 | 11 (13.6%) |

| Triple Negative | 14 (17.3%) |

| Chemotherapy Regimen | |

| Anthracycline-based (AC, EC, LipodoxC) | 3 (3.7%) |

| Taxane-based | 11 (13.6%) |

| Anthracycline + taxane sequential | 67 (82.7%) |

| Chemotherapy Type | |

| Neoadjuvant | 26 (32.1%) |

| Adjuvant | 50 (61.7%) |

| Palliative | 5 (6.2%) |

| Molecular Subgroup of Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy (n = 26) | |

| Luminal A | 2 (7.7%) |

| Luminal B | 9 (34.6%) |

| Luminal Her2 | 3 (11.5%) |

| Her2 | 4 (15.4%) |

| Triple Negative | 8 (30.8) |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (n = 26) | |

| pCR | 7 (26.9%) |

| No pCR | 19 (73.1%) |

| Hormone therapy | |

| Yes | 56 (69.1%) |

| No | 25 (30.9%) |

| Recurrence | |

| No | 70 (86.4%) |

| Yes | 6 (7.4%) |

| stage IV | 5 (6.2%) |

| pCR: pathologic complete response | |

| AC: Adriamycin and Cyclophosphamide | |

| EC: Epirubicin and Cyclophosphamide | |

| LipodoxC: Liposomal doxorubicin and Cyclophosphamide | |

| Chemotherapy Side Effect Grading | |

|---|---|

| Anemia | Patient No. (%) |

| 0 | 29 (35.8) |

| 1 | 31 (38.3) |

| 2 | 14 (17.3) |

| 3 | 7 (8.6) |

| Neutropenia | |

| 0 | 3 (3.7) |

| 1 | 5 (6.2) |

| 2 | 7 (8.6) |

| 3 | 14 (17.3) |

| 4 | 52 (64.2) |

| Thrombocytopenia | |

| 0 | 60 (74.1) |

| 1 | 20 (24.7) |

| 2 | 1 (1.2) |

| AST(GOT) Elevation | |

| 0 | 59 (72.8) |

| 1 | 20 (24.7) |

| 2 | 1 (1.2) |

| 3 | 1 (1.2) |

| AST(GOT) Elevation | |

| 0 | 42 (51.9) |

| 1 | 35 (43.2) |

| 2 | 2 (2.5) |

| 3 | 2 (2.5) |

| Nausea | |

| 0 | 58 (71.6) |

| 1 | 22 (27.2) |

| 2 | 1 (1.2) |

| Oral Mucositis | |

| 0 | 68 (84.0) |

| 1 | 12 (14.8) |

| 2 | 1 (1.2) |

| Diarrhea | |

| 0 | 49 (60.5) |

| 1 | 22 (27.2) |

| 2 | 10 (12.3) |

| Peripheral Neuropathy | |

| 0 | 40 (49.4) |

| 1 | 29 (35.8) |

| 2 | 7 (8.6) |

| 3 | 5 (6.2) |

| Skin Rash | |

| 0 | 63 (77.8) |

| 1 | 13 (16.0) |

| 2 | 4 (4.9) |

| 3 | 1 (1.2) |

| Hand Food Syndrome | |

| 0 | 70 (86.4) |

| 1 | 8 (9.9) |

| 2 | 3 (3.7) |

| Fatique | |

| 0 | 50 (61.7) |

| 1 | 28 (34.6) |

| 2 | 3 (3.7) |

| Linear Discriminant Analysis of Gut Microbiota Taxa Associated with Chemotherapy-Related Adverse Events | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse Event | Taxonomic Level | Taxa | With AE (Mean) | Without AE (Mean) | LDA Score | Effect Size | Significance |

| ANEMIA | Family | Erysipelotrichaceae | 190.1 | 140.17 | 2.8 | Large | Bio Sig* |

| ANEMIA | Family | Clostridiaceae | 3824.2 | 4147.1 | 4.37 | Large | Bio Sig* |

| ANEMIA | Genus | Coprococcus | 194.5 | 104.52 | 2.61 | Negligible | Nominal Sig |

| ANEMIA | Genus | Clostridium | 2812.5 | 2323.96 | 2.12 | Large | Bio Sig* |

| ANEMIA | Species | [Eubacterium]_rectale | 731.7 | 693.08 | 1.65 | Negligible | Nominal Sig |

| ANEMIA | Species | Coprococcus_catus | 1613.9 | 1534.5 | 1.6 | Negligible | Nominal Sig |

| ANEMIA | Species | Eubacterium_sp. | 67.6 | 58.52 | 2.35 | Large | Bio Sig* |

| ANEMIA | Species | Bacteroides_thetaiotaomicron_group | 39,132 | 15,068 | 2.87 | Large | Bio Sig* |

| ANEMIA | Species | Akkermansia_muciniphila | 3770 | 160.17 | 2.19 | Large | Bio Sig* |

| ANEMIA | Species | Massilimicrobium_timonense | 221.24 | 19.246 | 2.01 | Large | Bio Sig* |

| ANEMIA | Species | Clostridium_sporogenes | 330.11 | 81.004 | 1.7 | Large | Bio Sig* |

| NEUTROPENIA (Severe) | Family | Clostridiaceae/Lachnospiraceae_Sedis | 530.56 | 641.16 | −1.75 | Medium | Bio Sig* |

| NEUTROPENIA (Severe) | Genus | Eubacterium_hallii_group | 4382 | 2043.4 | −3.91 | Large | Bio Sig* |

| NEUTROPENIA (Severe) | Genus | Roseburia | 266.26 | 200.66 | 1.52 | Small | Nominal Sig |

| NEUTROPENIA (Severe) | Species | Intestinimonas_butyriciproducens | 135.39 | 683.13 | −2.44 | Large | Bio Sig* |

| THROMBOCYTOPENIA | Genus | Eubacterium | 39.127 | 2055 | −3 | Large | Bio Sig* |

| THROMBOCYTOPENIA | Species | Blautia_luti/Faecalibacterium_prausnitzii | 30.127 | 2055 | −3 | Large | Bio Sig* |

| AST(GOT) ELEVATION | Family | Akkermansiaceae | 7241.4 | 2961.2 | −4.03 | Large | Bio Sig* |

| AST(GOT) ELEVATION | Genus | Ruminococcaceae | 167,140 | 92,946 | 4.58 | Small | Nominal Sig |

| AST(GOT) ELEVATION | Genus | Bacteroidaceae | 348,710 | 469,440 | −4.85 | Small | Nominal Sig |

| AST(GOT) ELEVATION | Genus | Butyricicoccus | 3273.4 | 1181.7 | 3.02 | Medium | Bio Sig* |

| AST(GOT) ELEVATION | Genus | Akkermansia | 7241.4 | 2961.2 | −4.03 | Large | Bio Sig* |

| AST(GOT) ELEVATION | Species | Subdoligranulum_variabile | 1790.1 | 3840.3 | 3.82 | Large | Bio Sig* |

| AST(GOT) ELEVATION | Species | metagenome | 7560.1 | 881.63 | 3.52 | Large | Bio Sig* |

| ALT(GPT) ELEVATION | Family | Burkholderiaceae | 65.263 | 19.485 | −3.65 | Medium | Bio Sig* |

| ALT(GPT) ELEVATION | Genus | Haemilus | 864.79 | 810.78 | −2.89 | Negligible | Nominal Sig |

| ALT(GPT) ELEVATION | Genus | Acidaminococcaceae | 16243 | 32,737 | −3.92 | Medium | Bio Sig* |

| ALT(GPT) ELEVATION | Genus | Eubacterium_hallii_group | 3949.8 | 1582.8 | −3.77 | Large | Bio Sig* |

| ALT(GPT) ELEVATION | Genus | Burkholderia_Caballeronia_Para | 172.99 | 1039.3 | −2.64 | Large | Bio Sig* |

| NAUSEA | Species | Intestinimonas_butyriciproducens | 449.56 | 17.621 | 2.34 | Large | Bio Sig* |

| NAUSEA | Species | Christensenella_minuta | 62.35 | 0 | 1.51 | Large | Bio Sig* |

| NAUSEA | Species | Faecalibacterium_prausnitzii | 1296.3 | 159.51 | 2.76 | Large | Bio Sig* |

| NAUSEA | Species | Bacteroides_coprocola_DSM_17136 | 27,895 | 72,430 | −4.35 | Medium | Not Sig |

| ORAL MUCOSITIS | Genus | Coprococcus_2 | 3366.8 | 614 | 3.14 | Large | Bio Sig* |

| ORAL MUCOSITIS | Genus | Ruminococcaceae_UCG_014 | 6478.8 | 0 | 3.51 | Large | Bio Sig* |

| ORAL MUCOSITIS | Species | guL_metagenome | 33196 | 12369 | 4.02 | Medium | Bio Sig* |

| DIARRHEA | Genus | Christensenella | 72.482 | 3.5995 | 1.35 | Large | Bio Sig* |

| DIARRHEA | Species | Christensenella_minuta | 72.482 | 3.5995 | 1.35 | Large | Bio Sig* |

| PERIPHERAL NEUROPATHY | Species | Clostridium_scindens | 122.67 | 51.06 | 1.57 | Medium | Bio Sig* |

| SKIN RASH | Species | Bacteroides_ovatus | 1111.8 | 852.16 | 2.12 | Small | Nominal Sig |

| HAND-FOOT SYNDROME | Family | Erysipelotrichaceae | 125.09 | 188.11 | −3.77 | Large | Bio Sig* |

| HAND-FOOT SYNDROME | Genus | Lachnospiraceae | 115490 | 206780 | −4.61 | Small | Nominal Sig |

| HAND-FOOT SYNDROME | Genus | Butyricicoccus | 1703.5 | 8535.8 | −3.5 | Small | Nominal Sig |

| HAND-FOOT SYNDROME | Genus | Roseburia | 5545.1 | 2057.1 | −3.88 | Large | Small & Bio Sig*** |

| FATIGUE | Species | Bacteroides_vulgatus | 39121 | 72232 | −4.22 | Small | Nominal Sig |

| LEGEND | |||||||

| Significance Categories: | |||||||

| Bio Sig* (Biologically Significant) | FDR p < 0.05 AND Cohen’s d > 0.5—Statistically robust AND biologically meaningful | ||||||

| Nominal Sig | p < 0.05, d ≤ 0.5 (FDR p ≥ 0.05)—Statistically significant but small effect | ||||||

| Small & Bio Sig*** | p < 0.05, d ≥ 0.05 (Cohen’s d > 0.5)—Nominal biological relevance | ||||||

| Not Sig | p ≥ 0.05—No statistical significance | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hsu, J.-W.; Su, Y.-W.; Tsai, C.-H.; Lee, C.-C.; Yang, H.-W.; Lee, J.-J.; Hsu, H.-H.; Lee, F.; Yang, P.-S. Gut Microbiota Signatures Associate with Chemotherapy-Related Adverse Events in Breast Cancer Patients. Cancers 2025, 17, 3783. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233783

Hsu J-W, Su Y-W, Tsai C-H, Lee C-C, Yang H-W, Lee J-J, Hsu H-H, Lee F, Yang P-S. Gut Microbiota Signatures Associate with Chemotherapy-Related Adverse Events in Breast Cancer Patients. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3783. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233783

Chicago/Turabian StyleHsu, Jiun-Wei, Ying-Wen Su, Chung-Hsin Tsai, Chi-Chan Lee, Horng-Woei Yang, Jie-Jen Lee, Hsi-Hsien Hsu, Fang Lee, and Po-Sheng Yang. 2025. "Gut Microbiota Signatures Associate with Chemotherapy-Related Adverse Events in Breast Cancer Patients" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3783. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233783

APA StyleHsu, J.-W., Su, Y.-W., Tsai, C.-H., Lee, C.-C., Yang, H.-W., Lee, J.-J., Hsu, H.-H., Lee, F., & Yang, P.-S. (2025). Gut Microbiota Signatures Associate with Chemotherapy-Related Adverse Events in Breast Cancer Patients. Cancers, 17(23), 3783. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233783