Neighborhood Disadvantage and Cardiovascular Mortality Among Colorectal Cancer Survivors

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Population and Data

2.2. Primary Exposure

2.3. Outcome

2.4. Covariates

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Population Characteristics

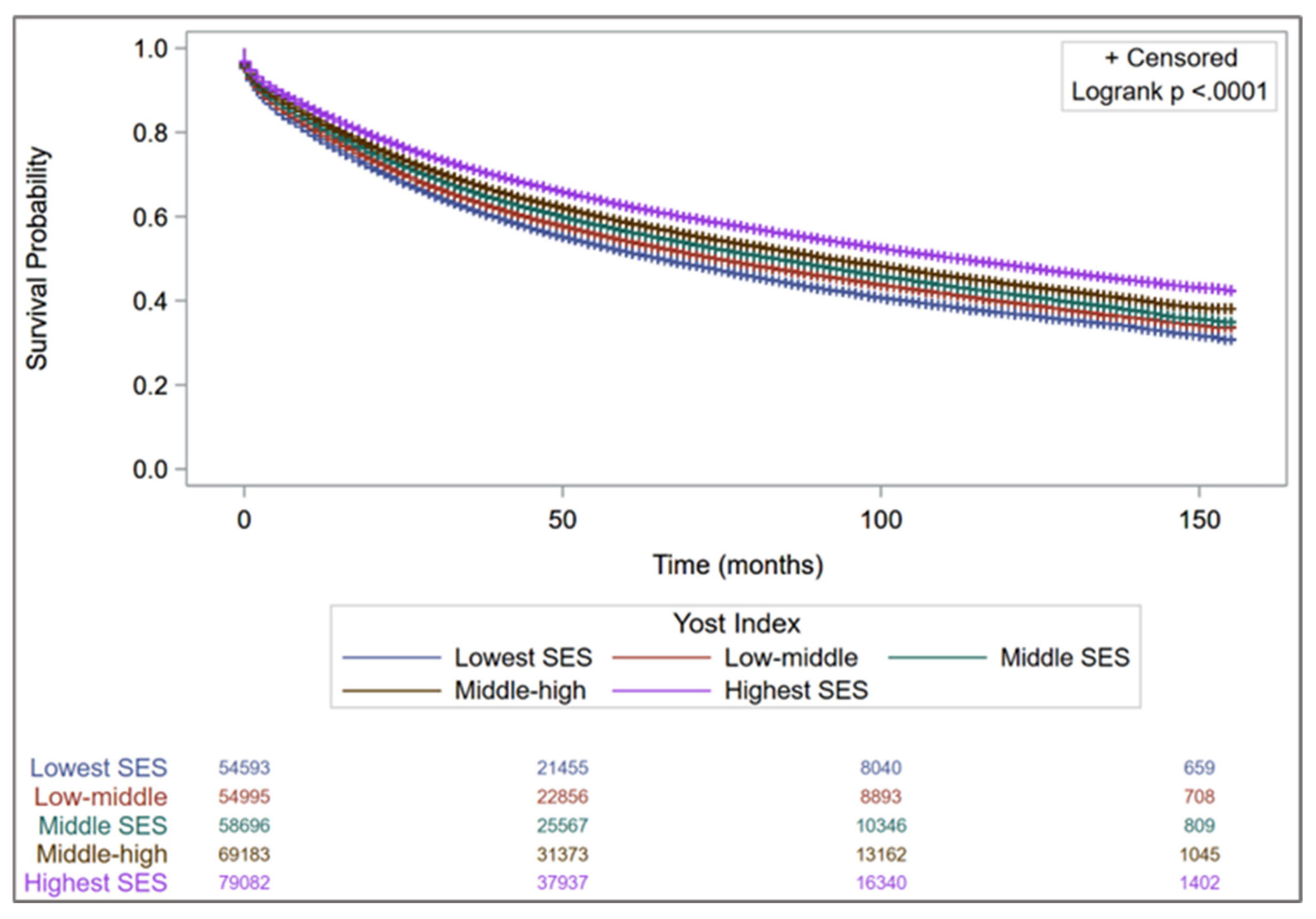

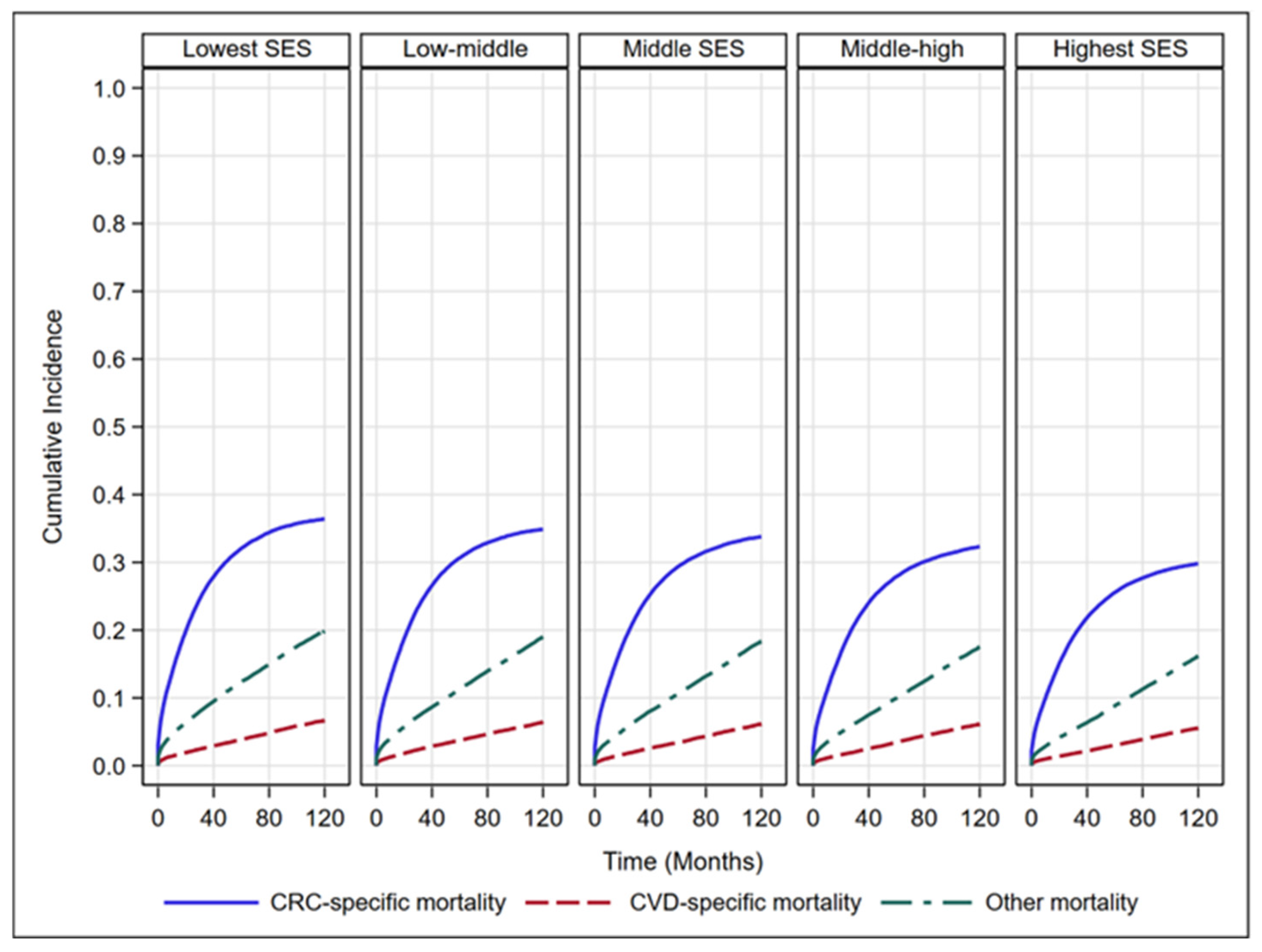

3.2. Survival Analysis

3.3. Effect Modification

4. Discussion

4.1. Treatment-Related Factors

4.2. Psychological and Biological Pathways

4.3. Physical Environment and Health Behaviors

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Kratzer, T.B.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2025, 75, 10–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Cancer Institute. Cancer Stat Facts: Colorectal Cancer. Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/colorect.html (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- American Cancer Society: Key Statistics for Colorectal Cancer. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/colon-rectal-cancer/about/key-statistics.html (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Weaver, K.E.; Foraker, R.E.; Alfano, C.M.; Rowland, J.H.; Arora, N.K.; Bellizzi, K.M.; Hamilton, A.S.; Oakley-Girvan, I.; Keel, G.; Aziz, N.M. Cardiovascular risk factors among long-term survivors of breast, prostate, colorectal, and gynecologic cancers: A gap in survivorship care? J. Cancer Surviv. 2013, 7, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Florido, R.; Daya, N.R.; Ndumele, C.E.; Koton, S.; Russell, S.D.; Prizment, A.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Matsushita, K.; Mok, Y.; Felix, A.S.; et al. Cardiovascular Disease Risk Among Cancer Survivors. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 80, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zullig, L.L.; Smith, V.A.; Lindquist, J.H.; Williams, C.D.; Weinberger, M.; Provenzale, D.; Jackson, G.L.; Kelley, M.J.; Danus, S.; Bosworth, H.B. Cardiovascular disease-related chronic conditions among Veterans Affairs nonmetastatic colorectal cancer survivors: A matched case-control analysis. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, 11, 6793–6802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhu, H.; Hu, H.; Hu, H.; Zhan, W.; Jiang, L.; Tang, M.; Escobar, D.; Huang, W.; Feng, Y.; et al. Cardiovascular-specific mortality and risk factors in colorectal Cancer patients: A cohort study based on registry data of over 500,000 individuals in the US. Prev. Med. 2024, 179, 107796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koene, R.J.; Prizment, A.E.; Blaes, A.; Konety, S.H. Shared risk factors in cardiovascular disease and cancer. Circulation 2016, 133, 1104–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Ai, L.; Liu, T. Cardiovascular Outcomes in the Patients With Colorectal Cancer: A Multi-Registry-Based Cohort Study of 197,699 Cases in the Real World. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 851833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhandiramge, J.; Zalcberg, J.R.; van Londen, G.J.; Warner, E.T.; Carr, P.R.; Haydon, A.; Orchard, S.G. Cardiovascular Disease in Adult Cancer Survivors: A Review of Current Evidence, Strategies for Prevention and Management, and Future Directions for Cardio-oncology. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2022, 24, 1579–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleman, B.M.; Moser, E.C.; Nuver, J.; Suter, T.M.; Maraldo, M.V.; Specht, L.; Vrieling, C.; Darby, S.C. Cardiovascular disease after cancer therapy. Eur. J. Cancer Suppl. 2014, 12, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, N.S.; Amit, U.; Reibel, J.B.; Berlin, E.; Howell, K.; Ky, B. Cardiovascular disease and cancer: Shared risk factors and mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2024, 21, 617–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturgeon, K.M.; Deng, L.; Bluethmann, S.M.; Zhou, S.; Trifiletti, D.M.; Jiang, C.; Kelly, S.P.; Zaorsky, N.G. A population-based study of cardiovascular disease mortality risk in US cancer patients. Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 3889–3897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ksinan, A.J.; Vazsonyi, A.T. Understanding neighborhood disadvantage: A behavior genetic analysis. J. Crim. Justice 2021, 73, 101782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malla, G.; Long, D.L.; Cherrington, A.; Goyal, P.; Guo, B.; Safford, M.M.; Khodneva, Y.; Cummings, D.M.; McAlexander, T.P.; DeSilva, S. Neighborhood disadvantage and risk of heart failure: The Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2024, 17, e009867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kershaw, K.N.; Magnani, J.W.; Diez Roux, A.V.; Camacho-Rivera, M.; Jackson, E.A.; Johnson, A.E.; Magwood, G.S.; Morgenstern, L.B.; Salinas, J.J.; Sims, M.; et al. Neighborhoods and Cardiovascular Health: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2024, 17, e000124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.Y.; Graham, G. Where we live: The impact of neighborhoods and community factors on cardiovascular health in the United States. Clin. Cardiol. 2019, 42, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashyap, M.K.; Mangrulkar, S.V.; Kushwaha, S.; Ved, A.; Kale, M.B.; Wankhede, N.L.; Taksande, B.G.; Upaganlawar, A.B.; Umekar, M.J.; Koppula, S.; et al. Recent Perspectives on Cardiovascular Toxicity Associated with Colorectal Cancer Drug Therapy. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danos, D.M.; Ferguson, T.F.; Simonsen, N.R.; Leonardi, C.; Yu, Q.; Wu, X.C.; Scribner, R.A. Neighborhood disadvantage and racial disparities in colorectal cancer incidence: A population-based study in Louisiana. Ann. Epidemiol. 2018, 28, 316–321.e312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaitanidis, A.; Spathakis, M.; Tsalikidis, C.; Alevizakos, M.; Tsaroucha, A.; Pitiakoudis, M. Risk factors for cardiovascular mortality in patients with colorectal cancer: A population-based study. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 24, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yost, K.; Perkins, C.; Cohen, R.; Morris, C.; Wright, W. Socioeconomic status and breast cancer incidence in California for different race/ethnic groups. Cancer Causes Control 2001, 12, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boscoe, F.P.; Liu, B.; Lee, F. A comparison of two neighborhood-level socioeconomic indexes in the United States. Spat. Spatiotemporal Epidemiol. 2021, 37, 100412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomans-Kropp, H.A.; Elsaid, M.I.; Kweon, Y.; Noonan, A.M.; Stanich, P.P.; Plascak, J.; Kalady, M.F.; Doubeni, C.A.; Paskett, E.D. Neighborhood level socioeconomic disparities are associated with reduced colorectal cancer survival. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 32795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, H.S.; Meng, R.; Marin, T.S.; Damarell, R.A.; Buckley, E.; Selvanayagam, J.B.; Koczwara, B. Cardiovascular mortality in people with cancer compared to the general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Med. 2024, 13, e70057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arun, A.S.; Sawano, M.; Lu, Y.; Warner, F.; Caraballo, C.; Khera, R.; Echols, M.R.; Yancy, C.W.; Krumholz, H.M. Excess Cardiovascular Mortality Among Black Americans 2000–2022. JACC 2024, 84, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, T.; Monteiro, O.; Chen, D.; Luo, Z.; Chi, K.; Li, Z.; Liang, Y.; Lu, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, J. Long-term and short-term cardiovascular disease mortality among patients of 21 non-metastatic cancers. J. Adv. Res. 2025, 69, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. SEER*Stat Database: Incidence—SEER Research Data, 18 Registries (2000–2018), National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Released April 2021, Based on the November 2020 Submission. Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/data-software/documentation/seerstat/nov2020/ (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Cuschieri, S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2019, 13, S31–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, N.; Hernandez, A.E.; Mazul, A. Neighborhood Disadvantage and Breast Cancer–Specific Survival in the US. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e247336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, J.L.; Stinchcomb, D.G.; Yu, M. Providing Higher Resolution Indicators of Rurality in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Database: Implications for Patient Privacy and Research. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2019, 28, 1409–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.K.; Irace, A.L.; Overdevest, J.B.; Turner, J.H.; Patel, Z.M.; Gudis, D.A. Association of Race, Ethnicity, and Socioeconomic Status With Esthesioneuroblastoma Presentation, Treatment, and Survival. OTO Open 2022, 6, 2473974x221075210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.J.; Zhang, X.; Scheike, T.H. Modeling cumulative incidence function for competing risks data. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008, 1, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, D.R. Regression models and life-tables. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 1972, 34, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.Y.; Wei, L.J.; Ying, Z. Checking the Cox model with cumulative sums of martingale-based residuals. Biometrika 1993, 80, 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uno, H.; Claggett, B.; Tian, L.; Inoue, E.; Gallo, P.; Miyata, T.; Schrag, D.; Takeuchi, M.; Uyama, Y.; Zhao, L.; et al. Moving beyond the hazard ratio in quantifying the between-group difference in survival analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 2380–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Wen, W.; Shrubsole, M.J.; Lipworth, L.E.; Mumma, M.T.; Ackerly, B.A.; Shu, X.O.; Blot, W.J.; Zheng, W. Impacts of Poverty and Lifestyles on Mortality: A Cohort Study in Predominantly Low-Income Americans. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2024, 67, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringhini, S.; Carmeli, C.; Jokela, M.; Avendaño, M.; Muennig, P.; Guida, F.; Ricceri, F.; d’Errico, A.; Barros, H.; Bochud, M.; et al. Socioeconomic status and the 25 × 25 risk factors as determinants of premature mortality: A multicohort study and meta-analysis of 1.7 million men and women. Lancet 2017, 389, 1229–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelli, M.B.; Bongiovanni, C.; Da Pra, S.; Miano, C.; Sacchi, F.; Lauriola, M.; D’Uva, G. Cardiotoxicity of Anticancer Drugs: Molecular Mechanisms and Strategies for Cardioprotection. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 847012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, E.T.; Bickford, C.L. Cardiovascular complications of cancer therapy: Incidence, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 53, 2231–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barac, A.; Murtagh, G.; Carver, J.R.; Chen, M.H.; Freeman, A.M.; Herrmann, J.; Iliescu, C.; Ky, B.; Mayer, E.L.; Okwuosa, T.M.; et al. Cardiovascular Health of Patients With Cancer and Cancer Survivors: A Roadmap to the Next Level. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 65, 2739–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfson, J.A.; Sun, C.L.; Wyatt, L.P.; Hurria, A.; Bhatia, S. Impact of care at comprehensive cancer centers on outcome: Results from a population-based study. Cancer 2015, 121, 3885–3893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloysius, M.M.; Goyal, H.; Shah, N.J.; Pallav, K.; John, N.; Gajendran, M.; Perisetti, A.; Tharian, B. Impact of Race and Socioeconomics Disparities on Survival in Young-Onset Colorectal Adenocarcinoma-A SEER Registry Analysis. Cancers 2021, 13, 3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carethers, J.M.; Doubeni, C.A. Causes of Socioeconomic Disparities in Colorectal Cancer and Intervention Framework and Strategies. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 354–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, J.R.M.; Phipps, A.I.; Barrington, W.E.; Hurvitz, P.M.; Sheppard, L.; Malen, R.C.; Newcomb, P.A. Associations of Household Income with Health-Related Quality of Life Following a Colorectal Cancer Diagnosis Varies With Neighborhood Socioeconomic Status. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2021, 30, 1366–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, K.X.; Yuan, W.J.; Huang, C.H.; Xiao, L.; Xiao, R.S.; Zeng, P.W.; Chen, L.; Chen, Z.H. Socioeconomic deprivation and survival outcomes in patients with colorectal cancer. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2022, 12, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Planey, A.M.; Spees, L.P.; Biddell, C.B.; Waters, A.; Jones, E.P.; Hecht, H.K.; Rosenstein, D.; Wheeler, S.B. The intersection of travel burdens and financial hardship in cancer care: A scoping review. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2024, 8, pkae093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanzo, E.S.; Sood, A.K.; Lutgendorf, S.K. Biobehavioral influences on cancer progression. Immunol. Allergy Clin. N. Am. 2011, 31, 109–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A.; Zhao, W.; Wang, X.; Ratliff, S.M.; Mukherjee, B.; Kardia, S.L.R.; Liu, Y.; Roux, A.V.D.; Needham, B.L. Neighborhood characteristics influence DNA methylation of genes involved in stress response and inflammation: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Epigenetics 2017, 12, 662–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoni, M.H.; Dhabhar, F.S. The impact of psychosocial stress and stress management on immune responses in patients with cancer. Cancer 2019, 125, 1417–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S.W. The Conserved Transcriptional Response to Adversity. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2019, 28, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B.S. Sex, stress and the hippocampus: Allostasis, allostatic load and the aging process. Neurobiol. Aging 2002, 23, 921–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, H.S.; Gomez, S.L.; Cheng, I.; Rebbeck, T.R. Relative impact of genetic ancestry and neighborhood socioeconomic status on all-cause mortality in self-identified African Americans. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0273735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S.W.; Nagaraja, A.S.; Lutgendorf, S.K.; Green, P.A.; Sood, A.K. Sympathetic nervous system regulation of the tumour microenvironment. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2015, 15, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.; Liu, Z.; Molinari, M. From Diagnosis to Survivorship: The Role of Social Determinants in Cancer Care. Cancers 2025, 17, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren Andersen, S.; Blot, W.J.; Lipworth, L.; Steinwandel, M.; Murff, H.J.; Zheng, W. Association of Race and Socioeconomic Status With Colorectal Cancer Screening, Colorectal Cancer Risk, and Mortality in Southern US Adults. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e1917995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazoukis, G.; Loscalzo, J.; Hall, J.L.; Bollepalli, S.C.; Singh, J.P.; Armoundas, A.A. Impact of Social Determinants of Health on Cardiovascular Disease. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2025, 14, e039031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, S.; Hickson, D.A.; Kawachi, I.; Subramanian, S.V.; Earls, F. Neighborhood Disadvantage and Cumulative Biological Risk Among a Socioeconomically Diverse Sample of African American Adults: An Examination in the Jackson Heart Study. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2016, 3, 444–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics n (%) | Group 1 (n = 54,593) | Group 2 (n = 54,995) | Group 3 (n = 58,696) | Group 4 (n = 69,183) | Group 5 (n = 79,082) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group, y | |||||

| 20–49 | 6572 (12.0) | 6438 (11.7) | 7095 (12.1) | 8415 (12.2) | 10,339 (13.1) |

| 50–64 | 20,264 (37.1) | 19,266 (35.0) | 20,246 (34.5) | 23,664 (34.2) | 26,808 (33.9) |

| 65–74 | 13,937 (25.5) | 14,019 (25.5) | 14,319 (24.4) | 16,568 (23.9) | 18,290 (23.1) |

| ≥75 | 13,820 (25.3) | 15,272 (27.8) | 17,036 (29.0) | 20,536 (29.7) | 23,645 (29.9) |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 26,067 (47.7) | 26,371 (47.9) | 28,130 (47.9) | 33,222 (48.0) | 37,737 (47.7) |

| Male | 28,526 (52.3) | 28,624 (52.1) | 30,566 (52.1) | 35,961 (52.0) | 41,345 (52.3) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| NH-White | 26,250 (48.0) | 34,846 (63.4) | 39,906 (68.0) | 49,380 (71.4) | 58,999 (74.6) |

| NH-Black | 16,935 (31.0) | 8072 (14.7) | 5896 (10.0) | 5031 (7.3) | 3361 (4.2) |

| Hispanic | 8641 (15.8) | 8232 (15.0) | 7636 (13.0) | 6769 (9.8) | 5412 (6.8) |

| NH-Asian/PI | 2322 (4.2) | 3295 (6.0) | 4691 (8.0) | 7333 (10.6) | 10,383 (13.1) |

| NH-AI/AN | 276 (0.5) | 310 (0.6) | 271 (0.5) | 248 (0.4) | 217 (0.3) |

| Unknown | 169 (0.3) | 240 (0.4) | 296 (0.5) | 422 (0.6) | 710 (0.9) |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married/Partnered | 23,268 (42.6) | 27,051 (49.2) | 30,759 (52.4) | 37,967 (54.9) | 47,991 (61.0) |

| Other | 31,325 (57.4) | 27,944 (50.8) | 27,937 (47.6) | 31,216 (45.1) | 31,091 (39.0) |

| Year of diagnosis | |||||

| 2006–2008 | 13,074 (23.9) | 13,488 (24.5) | 14,989 (25.5) | 18,357 (26.5) | 21,321 (27.0) |

| 2009–2011 | 13,485 (24.7) | 13,865 (25.2) | 14,693 (25.0) | 17,379 (25.1) | 19,743 (24.5) |

| 2012–2014 | 14,123 (25.9) | 13,906 (25.3) | 14,555 (24.8) | 16,840 (24.3) | 18,959 (24.0) |

| 2015–2017 | 13,911 (25.5) | 13,736 (25.0) | 14,459 (24.6) | 16,607 (24.0) | 19,059 (24.1) |

| Stage | |||||

| Localized | 21,119 (38.7) | 21,669 (39.4) | 23,328 (39.7) | 28,023 (40.5) | 33,817 (42.0) |

| Regional | 20,240 (37.1) | 20,611 (37.5) | 22,343 (38.1) | 26,217 (37.9) | 29,788 (37.7) |

| Distant | 13,234 (24.2) | 12,715 (23.1) | 13,025 (22.2) | 14,943 (21.6) | 16,107 (20.4) |

| Tumor location | |||||

| Right colon | 20,925 (38.3) | 21,321 (38.8) | 22,923 (39.0) | 26,980 (38.9) | 30,559 (38.6) |

| Left colon | 15,040 (27.5) | 14,813 (26.9) | 15,942 (27.2) | 18,780 (27.1) | 21,226 (26.8) |

| Rectum | 16,747 (30.7) | 17,099 (31.1) | 18,090 (30.8) | 21,521 (31.1) | 25,262 (31.9) |

| Unspecified | 1881 (3.4) | 1762 (3.2) | 1741 (3.0) | 1992 (2.9) | 2035 (2.6) |

| Tumor grade | |||||

| Well-differentiated | 4918 (9.0) | 4912 (8.9) | 5229 (8.9) | 6136 (8.9) | 7563 (9.6) |

| Moderately differentiated | 33,051 (60.5) | 33,214 (60.4) | 35,562 (60.6) | 41,902 (60.6) | 46,918 (59.3) |

| Poorly differentiated | 6867 (12.6) | 7431 (13.5) | 8220 (14.0) | 10,046 (14.5) | 12,093 (15.3) |

| Undifferentiated or anaplastic | 1333 (2.4) | 1327 (2.4) | 1427 (2.4) | 1512 (2.2) | 1622 (2.0) |

| Unknown | 8424 (15.4) | 8111 (14.7) | 8258 (14.1) | 9587 (13.9) | 10,886 (13.8) |

| Surgery Receipt | |||||

| Yes | 44,882 (82.2) | 45,973 (83.6) | 49,786 (84.8) | 59,132 (85.5) | 68,166 (86.2) |

| No | 9711 (17.8) | 9022 (16.4) | 8910 (15.2) | 10,051 (14.5) | 10,916 (13.8) |

| Chemotherapy | |||||

| Yes | 21,428 (39.2) | 21,635 (39.3) | 23,273 (39.7) | 27,510 (39.8) | 31,934 (40.4) |

| No | 33,165 (60.8) | 33,360 (60.7) | 35,423 (60.3) | 41,673 (60.2) | 47,148 (59.6) |

| Radiation | |||||

| Yes | 7927 (14.5) | 8085 (14.7) | 8597 (14.6) | 9884 (14.3) | 11,195 (14.2) |

| No | 46,666 (85.5) | 46,910 (85.3) | 50,099 (85.4) | 59,299 (85.7) | 67,887 (85.8) |

| Months of follow-up, Median (IQR) | 36 (13–74) | 38 (38–79) | 41 (16–82) | 43 (17–86) | 47 (19–90) |

| Overall Mortality | CVD-Specific Mortality | Cancer-Specific Mortality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value |

| Yost Index | ||||||

| Group 5 (highest SES) | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Group 4 | 1.10 (1.06–1.14) | <0.001 | 1.07 (0.94–1.22) | <0.001 | 1.09 (1.06–1.11) | <0.001 |

| Group 3 | 1.18 (1.14–1.21) | <0.001 | 1.12 (1.01–1.25) | <0.001 | 1.15 (1.12–1.19) | <0.001 |

| Group 2 | 1.23 (1.20–1.26) | <0.001 | 1.24 (1.14–1.35) | <0.001 | 1.19 (1.15–1.24) | <0.001 |

| Group 1 (lowest SES) | 1.31 (1.28–1.33) | <0.001 | 1.39 (1.30–1.48) | <0.001 | 1.24 (1.18–1.30) | <0.001 |

| p-trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Yost Index Quintile | RMST (LCL to UCL) | Change in RMST (LCL to UCL) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 5 (highest SES) | 45.5 (45.3 to 45.6) | Ref | |

| Group 4 | 43.7 (43.6 to 43.9) | −1.8 (−1.9 to −1.5) | <0.0001 |

| Group 3 | 42.8 (42.6 to 43.9) | −2.7 (−2.9 to −2.4) | <0.0001 |

| Group 2 | 41.7 (41.5 to 41.9) | −3.8 (−4.0 to −3.5) | <0.0001 |

| Group 1 (lowest SES) | 40.5 (40.3 to 40.7) | −5.0 (−5.2 to −4.7) | <0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Valvi, N.; Groenewold, M.; Terracina, K.; Verma, H.; Shrestha, P.; Hitchcock, K.E.; Braithwaite, D.; Karanth, S.D. Neighborhood Disadvantage and Cardiovascular Mortality Among Colorectal Cancer Survivors. Cancers 2025, 17, 3782. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233782

Valvi N, Groenewold M, Terracina K, Verma H, Shrestha P, Hitchcock KE, Braithwaite D, Karanth SD. Neighborhood Disadvantage and Cardiovascular Mortality Among Colorectal Cancer Survivors. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3782. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233782

Chicago/Turabian StyleValvi, Nimish, Matthew Groenewold, Krista Terracina, Himanshi Verma, Pratibha Shrestha, Kathryn E. Hitchcock, Dejana Braithwaite, and Shama D. Karanth. 2025. "Neighborhood Disadvantage and Cardiovascular Mortality Among Colorectal Cancer Survivors" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3782. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233782

APA StyleValvi, N., Groenewold, M., Terracina, K., Verma, H., Shrestha, P., Hitchcock, K. E., Braithwaite, D., & Karanth, S. D. (2025). Neighborhood Disadvantage and Cardiovascular Mortality Among Colorectal Cancer Survivors. Cancers, 17(23), 3782. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233782