CAR Therapies: Ex Vivo and In Vivo Potential of Exosomes and Biomimetic Nanoparticles

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Structure of the CAR and Its Evolution

- (a)

- Extracellular Antigen-Binding Domain

- (b)

- Hinge Region (Spacer)

- (c)

- Transmembrane Domain

- (d)

- Intracellular Signaling Domains

3. Biological Nanoparticles: Classification and Properties

3.1. Extracellular Vesicles

- (a)

- Therapeutic Potential: The unique properties of ApoBDs open promising avenues for their use as natural, biocompatible platforms for the targeted delivery of therapeutic agents. Their innate ability to be efficiently taken up by various cell types, modulate immune responses, and carry protected cargo makes them ideal candidates for novel drug development [33]. Potential application strategies include:

- (b)

- Targeted Drug Delivery: Loading ApoBDs with chemotherapeutic agents, anti-cancer RNAs (e.g., siRNA), or immunomodulators allows for the exploitation of their natural uptake mechanism for targeted delivery to specific cells, such as macrophages or tumor cells, thereby enhancing therapeutic efficacy and reducing systemic toxicity [33].

- (c)

- Immunotherapy and Vaccines: Due to their capacity to carry a full spectrum of tumor-associated antigens from the parent cell, ApoBDs can be utilized to develop therapeutic anti-cancer vaccines, enhancing antigen presentation by dendritic cells and stimulating a specific T-cell-mediated immune response against the malignancy [33,34].

- (d)

- Regenerative Medicine: The ability of ApoBDs to transfer signaling molecules and organelles could be harnessed to stimulate reparative processes in damaged tissues, for instance, by delivering proliferative signals or mitochondria to restore cellular energy metabolism [33].

3.2. Biomimetic Nanoparticles

Core Materials Strategic: Selection and Function Characteristic

3.3. Biomimetic Shells: Biological Targeting Mechanisms

- (1)

- Red Blood Cell Membranes. This most common type of biomimetic shell confers long circulation times and enhanced tumor penetration. These properties are largely attributed to surface markers like CD47, which binds to the SIRPα receptor on macrophages to inhibit phagocytosis [40].

- (2)

- Platelet Membranes. This type contains surface proteins that promote targeted accumulation at sites of tumor neovascularization. Key mediators include adhesive molecules like P-selectin, which binds specifically to CD44 receptors on tumor cells. Other significant components are the CD40L ligand (involved in immune activation), integrins (CD41, CD61), and glycoproteins (CD42b) [41].

- (3)

- Leukocyte Membranes (e.g., neutrophils, macrophages). Membranes derived from leukocytes possess chemokine receptors that are recruited to pathological tissues by inflammatory signals. Surface receptors such as LFA-1 and Mac-1 facilitate specific binding to adhesion molecules (e.g., VCAM-1) on inflamed endothelium and tumor cells, enabling targeted nanoparticle delivery to diseased sites [41].

- (4)

- Cancer Cell Membranes. This type of membranes contains a unique profile of tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) and adhesion proteins (e.g., EpCAM, integrins) that serve as a tumor-specific “identification signature” [42]. When used to coat synthetic nanoparticles, these membranes create biomimetic systems capable of homotypic targeting: the retained surface proteins mediate specific binding to other cancer cells of the same type through natural cell-adhesion mechanisms. This approach promotes efficient tumor accumulation while simultaneously camouflaging the nanoparticle from immune recognition [8].

3.4. Virus-like Particles

- Hepatitis B Surface Antigen (HBsAg) VLPs

- Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) VLPs

- Bacteriophage VLPs

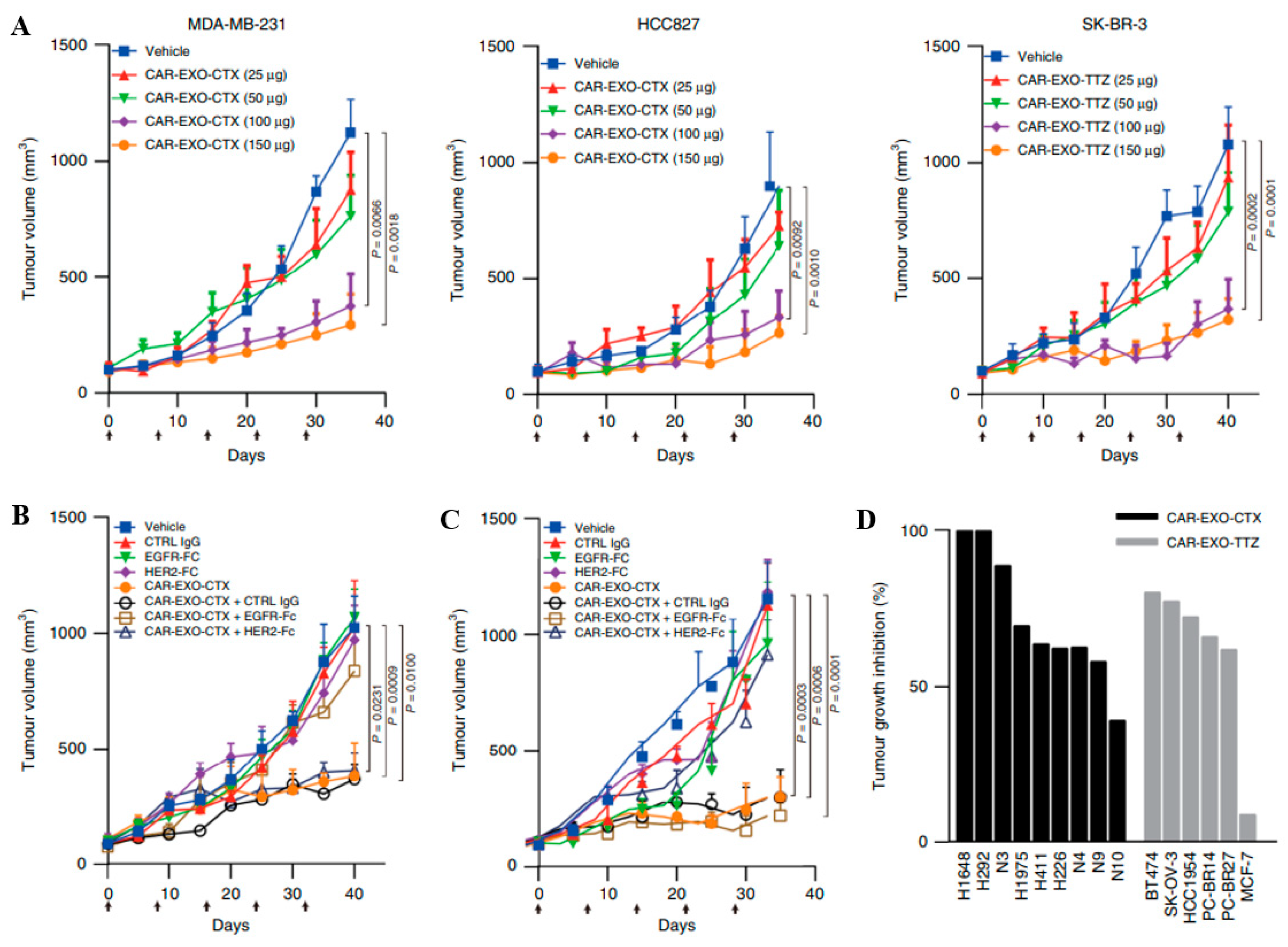

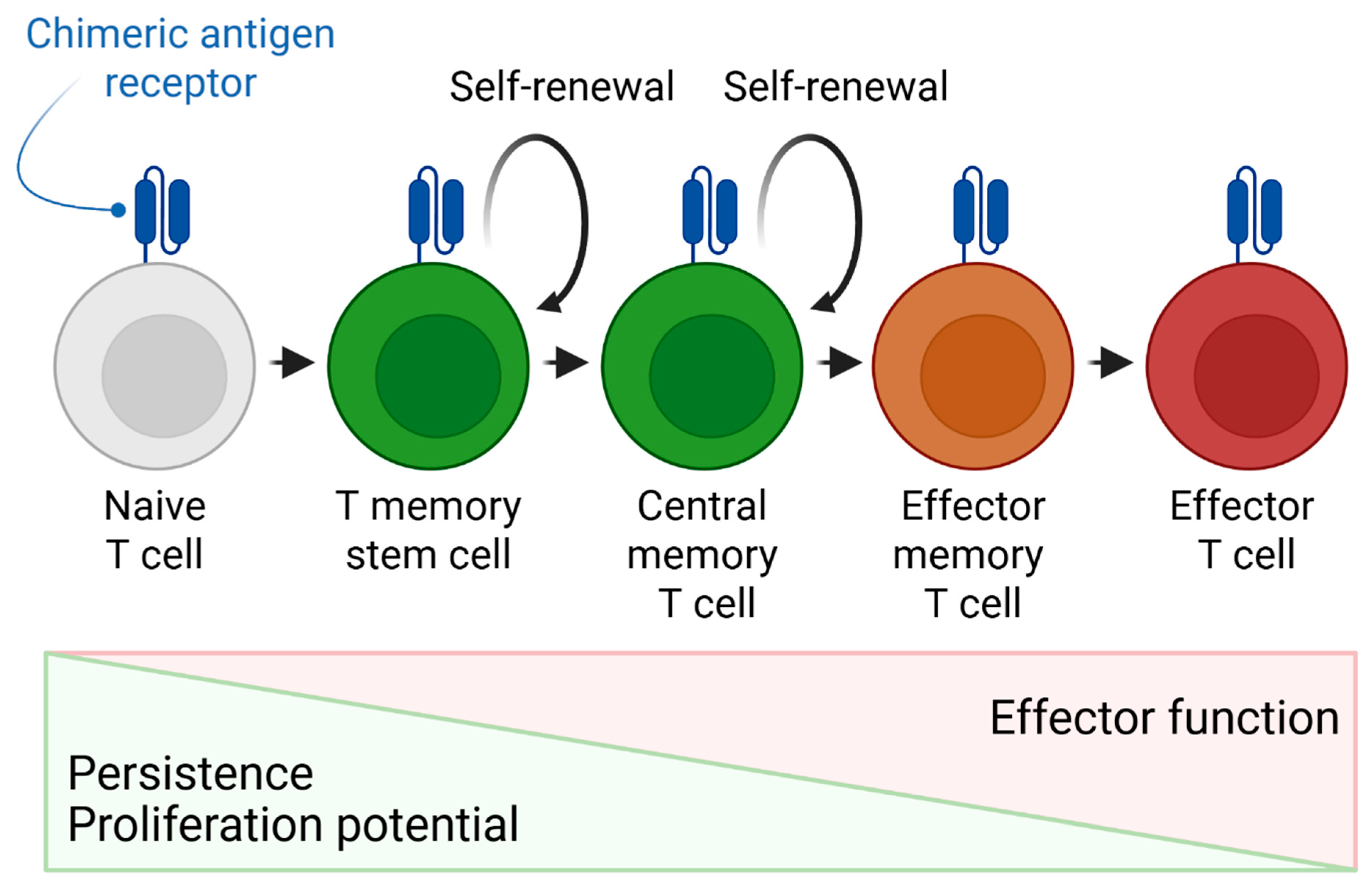

4. The Use of BNPs in CAR-T Therapy

- (a)

- The initial stage is the collection of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) of the patient by leukocyte apheresis, which allows selectively isolating the leukocyte fraction with minimal loss of cellular material. Then selective isolation of T-lymphocytes is carried out [55].

- (b)

- The key stage of CAR-T therapy is the introduction of the CAR gene into the genome of the patient’s T-lymphocytes, using vector transduction based on viral or non-viral systems. The most common vectors for transduction are those based on AAV or lentiviruses. After transduction, successfully modified cells are selected and then activated in vitro [56].

- (a)

- Activation is aimed at inducing proliferation and enhancing the efficiency of genetic modification. In vitro, physiological activation mediated by TCR and co-stimulatory signals (e.g., via CD28) is simulated using artificial stimuli. The most common method involves the use of magnetic nanoparticles conjugated with antibodies against CD3 and CD28 [61]. Additionally, cytokines (such as IL-2, IL-7, and IL-15) are employed to stimulate T cells [62].

- (b)

- Genetically modified CAR-T cells are administered to the patient intravenously as a slow infusion. Before the infusion of CART cells to the patient, lymphodepletion is performed, which helps to reduce the cytotoxic response of the body and provides favorable conditions for the proliferation of CAR-T cells [63].

4.1. In Vivo CAR Therapies

Challenges and Limitations of In Vivo CAR-T Cell Generation

4.2. Ex Vivo and In Vivo CAR Cell Engineering: Comparative Challenges and Delivery Platforms

5. Targeted Activation and In Vivo Control

6. Problems and Drawbacks

7. Review of Clinical Progress of the First FDA-Approved CCAR-T Therapies

7.1. Tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah): The First Approved CAR-T Therapy

7.2. Axicabtagene Ciloleucel (Yescarta): Advancing Lymphoma Treatment

7.3. Brexucabtagene Autoleucel (Tecartus): Optimized for B-ALL

7.4. Comparative Clinical Implications

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cappell, K.M.; Kochenderfer, J.N. Long-term outcomes following CAR T cell therapy: What we know so far. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 20, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chohan, K.L.; Siegler, E.L.; Kenderian, S.S. CAR-T Cell Therapy: The Efficacy and Toxicity Balance. Curr. Hematol. Malig. Rep. 2023, 18, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konoplya, N.E.; Kalenik, O.A.; Severin, I.N.; Savritskaya, A.A.; Bobrova, N.M.; Doroshenko, T.M.; Portyanko, A.S. Use of locally produced anti-CD19 CAR-T cells in the treatment of relapsed/refractory B-cell lymphomas in adults. Oncogematologiya 2023, 18, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponterio, E.; Haas, T.L.; De Maria, R. Oncolytic virus and CAR-T cell therapy in solid tumors. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1455163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tian, Y.; Li, C.; Fang, W.; Li, X.; Jing, Z.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Huang, Y.; Gong, J.; et al. In Situ engineering of mRNA-CAR T cells using spleen-targeted ionizable lipid nanoparticles to eliminate cancer cells. Nano Today 2024, 59, 102518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadelain, M.; Riddell, S.; Kettering, S.; Cancer, H. Therapeutic T cell engineering. Nature 2017, 545, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wherry, E.J.; Kurachi, M. Molecular and cellular insights into T cell exhaustion. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 15, 486–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, C.; Chen, C.; Gao, H.; Zhou, X.; Liu, T.; Qian, Q. Safety and Efficacy of an Immune Cell-Specific Chimeric Promoter in Regulating Anti-PD-1 Antibody Expression in CAR T Cells. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2020, 19, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagar, G.; Gupta, A.; Masoodi, T.; Nisar, S.; Merhi, M.; Hashem, S.; Chauhan, R.; Dagar, M.; Mirza, S.; Bagga, P.; et al. Harnessing the potential of CAR-T cell therapy: Progress, challenges, and future directions in hematological and solid tumor treatments. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelapu, S.S.; Tummala, S.; Kebriaei, P.; Wierda, W.; Gutierrez, C.; Locke, F.L.; Komanduri, K.V.; Lin, Y.; Jain, N.; Daver, N.; et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy—assessment and management of toxicities. Physiol. Behav. 2017, 176, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, K.; Farrukh, H.; Chittepu, V.C.S.R.; Xu, H.; Pan, C.-X.; Zhu, Z. CAR race to cancer immunotherapy: From CAR T, CAR NK to CAR macrophage therapy. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 41, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brezgin, S.; Danilik, O.; Yudaeva, A.; Kachanov, A.; Kostyusheva, A.; Karandashov, I.; Ponomareva, N.; Zamyatnin, A.A.J.; Parodi, A.; Chulanov, V.; et al. Basic Guide for Approaching Drug Delivery with Extracellular Vesicles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikhonov, A.; Kachanov, A.; Yudaeva, A.; Danilik, O.; Ponomareva, N.; Karandashov, I.; Kostyusheva, A.; Zamyatnin, A.A.J.; Parodi, A.; Chulanov, V.; et al. Biomimetic Nanoparticles for Basic Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, A.; Bagherifar, R.; Ansari Dezfouli, E.; Kiaie, S.H.; Jafari, R.; Ramezani, R. Exosomes as bio-inspired nanocarriers for RNA delivery: Preparation and applications. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitra, A.; Barua, A.; Huang, L.; Ganguly, S.; Feng, Q.; He, B. From bench to bedside: The history and progress of CAR T cell therapy. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1188049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiseleva, Y.Y.; Shishkin, A.M.; Ivanov, A.V.; Kulinich, T.M.; Bozhenko, V.K. CAR T-cell therapy of solid tumors: Promising approaches to modulating antitumor activity of CAR T cells. Bull. Russ. State Med. Univ. 2019, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, H.; Chen, S.; Xiao, Y. CAR-T Cell Therapy in Hematological Malignancies: Current Opportunities and Challenges. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 927153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Yoon, C.W.; Yuan, Z.; Guo, T.; Qu, Y.; He, P.; Yu, X.; Zhu, Z.; Limsakul, P.; Wang, Y. Cellular and molecular imaging of CAR-T cell-based immunotherapy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2023, 203, 115135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermanson, D.L.; Kaufman, D.S. Utilizing chimeric antigen receptors to direct natural killer cell activity. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalaitsidou, M.; Kueberuwa, G.; Schütt, A.; Gilham, D.E. CAR T-cell therapy: Toxicity and the relevance of preclinical models. Immunotherapy 2015, 7, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minciacchi, V.R.; Freeman, M.R.; Di Vizio, D. Extracellular vesicles in cancer: Exosomes, microvesicles and the emerging role of large oncosomes. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2015, 40, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Freitas, D.; Kim, H.S.; Fabijanic, K.; Li, Z.; Chen, H.; Mark, M.T.; Molina, H.; Martin, A.B.; Bojmar, L.; et al. Identification of distinct nanoparticles and subsets of extracellular vesicles by asymmetric flow field-flow fractionation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, C.; Wang, L.; Li, C. Bacterial outer membrane vesicles as drug delivery carrier for photodynamic anticancer therapy. Front. Chem. 2023, 11, 1284292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Guan, Y.; Xie, A.; Yan, Z.; Gao, S.; Li, W.; Rao, L.; Chen, X.; Chen, T. Extracellular vesicles: A rising star for therapeutics and drug delivery. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudin, Y. Characterization of the Equilibrium between the Native and Fusion-Inactive Conformation of Rabies Virus Glycoprotein Indicates That the Fusion Complex is Made of Several Trimers. Virology 2002, 135, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.-H.; Cerione, R.A.; Antonyak, M.A. Extracellular Vesicles and Their Roles in Cancer Progression. Methods Mol. Biol. 2021, 2174, 143–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowal, J.; Arras, G.; Colombo, M.; Jouve, M.; Morath, J.P.; Primdal-Bengtson, B.; Dingli, F.; Loew, D.; Tkach, M.; Théry, C. Proteomic comparison defines novel markers to characterize heterogeneous populations of extracellular vesicle subtypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E968–E977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura, E.; Nicco, C.; Lombard, B.; Véron, P.; Raposo, G.; Batteux, F.; Amigorena, S.; Théry, C. ICAM-1 on exosomes from mature dendritic cells is critical for efficient naive T-cell priming. Blood 2005, 106, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanada, M.; Bachmann, M.H.; Hardy, J.W.; Frimannson, D.O.; Bronsart, L.; Wang, A.; Sylvester, M.D.; Schmidt, T.L.; Kaspar, R.L.; Butte, M.J.; et al. Differential fates of biomolecules delivered to target cells via extracellular vesicles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E1433–E1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, C.; Zhao, Z.; Li, R.; Saw, P.E.; Xu, X. Advances in targeted delivery of mRNA into immune cells for enhanced cancer therapy. Theranostics 2024, 14, 5528–5550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akers, J.C.; Gonda, D.; Kim, R.; Carter, B.S.; Chen, C.C. Biogenesis of extracellular vesicles (EV): Exosomes, microvesicles, retrovirus-like vesicles, and apoptotic bodies. J. Neurooncol. 2013, 113, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratajczak, M.Z.; Ratajczak, J. Extracellular microvesicles/exosomes: Discovery, disbelief, acceptance, and the future? Leukemia 2020, 34, 3126–3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Luo, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, D. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Apoptotic Bodies: Biological Functions and Therapeutic Potential. Cells 2022, 11, 3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, T.K.; Ozkocak, D.C.; Poon, I.K.H. Unleashing the therapeutic potential of apoptotic bodies. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2020, 48, 2079–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeppesen, D.K.; Fenix, A.M.; Franklin, J.L.; Higginbotham, J.N.; Zhang, Q.; Zimmerman, L.J.; Liebler, D.C.; Ping, J.; Liu, Q.; Evans, R.; et al. Reassessment of Exosome Composition. Cell 2019, 177, 428–445.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostyusheva, A.; Romano, E.; Yan, N.; Lopus, M.; Zamyatnin, A.A.J.; Parodi, A. Breaking barriers in targeted Therapy: Advancing exosome Isolation, Engineering, and imaging. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2025, 218, 115522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alimohammadvand, S.; Kaveh Zenjanab, M.; Mashinchian, M.; Shayegh, J.; Jahanban-Esfahlan, R. Recent advances in biomimetic cell membrane-camouflaged nanoparticles for cancer therapy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 177, 116951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaman, S.; Ramachandramoorthy, H.; Oter, G.; Zhukova, D.; Nguyen, T.; Sabnani, M.K.; Weidanz, J.A.; Nguyen, K.T. Melanoma Peptide MHC Specific TCR Expressing T-Cell Membrane Camouflaged PLGA Nanoparticles for Treatment of Melanoma Skin Cancer. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Wu, M.; Chen, S.; Song, M.; Yue, Y. Biomimetic nanoparticles for tumor immunotherapy. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 989881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Wu, J.; Williams, G.R.; Fan, Q.; Niu, S.; Wu, J.; Xie, X.; Zhu, L.M. Platelet-membrane-biomimetic nanoparticles for targeted antitumor drug delivery. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2019, 17, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.; Lu, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhu, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Gong, P. Application and advances of biomimetic membrane materials in central nervous system disorders. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Krishnamachary, B.; Barnett, J.D.; Chatterjee, S.; Chang, D.; Mironchik, Y.; Wildes, F.; Jaffee, E.M.; Nimmagadda, S.; Bhujwalla, Z.M. Human Cancer Cell membrane Coated Biomimetic Nanoparticles Reduce Fibroblast-mediated Invasion and Metastasis, and Induce T Cells. J. Oncol. Transl. Res. 2018, 176, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nooraei, S.; Bahrulolum, H.; Hoseini, Z.S.; Katalani, C.; Hajizade, A.; Easton, A.J.; Ahmadian, G. Virus-like particles: Preparation, immunogenicity and their roles as nanovaccines and drug nanocarriers. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taghizadeh, M.S.; Niazi, A.; Afsharifar, A. Virus-like particles (VLPs): A promising platform for combating against Newcastle disease virus. Vaccine X 2024, 16, 100440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirbaghaee, Z.; Bolhassani, A. Different applications of virus-like particles in biology and medicine: Vaccination and delivery systems. Biopolymers 2016, 105, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Li, J. Vesicular Stomatitis Virus as a Vector To Deliver Virus-Like Particles of Human Norovirus: A New Vaccine Candidate against an Important Noncultivable Virus. J. Virol. 2015, 85, 2942–2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, J.M.; Her, L.; Varvel, V.; Lund, E.; Dahlberg, J.E. The Matrix Protein of Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Inhibits Nucleocytoplasmic Transport When It Is in the Nucleus and Associated with Nuclear Pore Complexes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000, 20, 8590–8601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Lu, A.; Nehlmeier, I.; Winkler, M.; Po, S. The glycoprotein of vesicular stomatitis virus promotes release of virus-like particles from tetherin-positive cells. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Somiya, M.; Kuroda, S. Elucidation of the early infection machinery of hepatitis B virus by using bio-nanocapsule. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 8489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinuma, S.; Fujita, K.; Kuroda, S. Binding of Nanoparticles Harboring Recombinant Large Surface Protein of Hepatitis B Virus to Scavenger Receptor. Viruses 2021, 13, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundstrom, K. Viral Vectors in Gene Therapy: Where Do We Stand in 2023? Viruses 2023, 15, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Yu, L.; Lin, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, F.; Deng, W. Virus-like Particles as Nanocarriers for Intracellular Delivery of Biomolecules and Compounds. Viruses 2022, 14, 1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.A.; Mei, H.; Sang, R.; Ortega, D.G.; Deng, W. Advancements and challenges in developing in vivo CAR T cell therapies for cancer treatment. eBioMedicine 2024, 106, 105266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uscanga-Palomeque, A.C.; Chávez-Escamilla, A.K.; Alvizo-Báez, C.A.; Saavedra-Alonso, S.; Terrazas-Armendáriz, L.D.; Tamez-Guerra, R.S.; Rodríguez-Padilla, C.; Alcocer-González, J.M. CAR-T Cell Therapy: From the Shop to Cancer Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umair, M.M.; Lai, X.; Xue, Y.B.; Yao, H. Influence of CAR T-cell therapy associated complications. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1494986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, E.F.; Lione, L.; Compagnone, M.; Paccagnella, M.; Salvatori, E.; Greco, M.; Frezza, V.; Marra, E.; Aurisicchio, L.; Roscilli, G.; et al. From ex vivo to in vivo chimeric antigen T cells manufacturing: New horizons for CAR T-cell based therapy. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, Z.; Shi, Y.; Jing, R.; Luo, D. CRISPR/Cas-based CAR-T cells: Production and application. Biomark. Res. 2024, 12, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostyushev, D.; Kostyusheva, A.; Brezgin, S.; Smirnov, V.; Volchkova, E.; Lukashev, A.; Chulanov, V. Gene Editing by Extracellular Vesicles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, T.; Zhong, J.; Pan, Q.; Zhou, T.; Ping, Y.; Liu, X. Exosome-mediated delivery of Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complexes for tissue-specific gene therapy of liver diseases. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabp9435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, P.; Lung, M.S.Y.; Okuzaki, Y.; Sasakawa, N.; Iguchi, T.; Makita, Y.; Hozumi, H.; Miura, Y.; Yang, L.F.; Iwasaki, M.; et al. Extracellular nanovesicles for packaging of CRISPR-Cas9 protein and sgRNA to induce therapeutic exon skipping. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Méndez, D.; Mendoza, L.; Villarreal, C.; Huerta, L. Continuous Modeling of T CD4 Lymphocyte Activation and Function. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 743559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, D.; Wong, R.A.; Yang, X.; Wang, D.; Pecoraro, J.R.; Kuo, C.F.; Aguilar, B.; Qi, Y.; Ann, D.K.; Starr, R.; et al. IL15 enhances CAR-T-cell antitumor activity by reducing mTORC1 activity and preserving their stem cell memory phenotype. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2019, 7, 759–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khawar, M.B.; Afzal, A.; Si, Y.; Sun, H. Steering the course of CAR T cell therapy with lipid nanoparticles. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitt, M.A. Vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein mutations that affect membrane fusion activity and abolish virus infectivity Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Glycoprotein Mutations That Affect Membrane Fusion Activity and Abolish Virus Infectivity. J. Virol. 1995, 69, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Zhu, D.; Li, J.; Chen, X.; Xie, W.; Jiang, X.; Wu, L.; Wang, G.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, Z.; et al. Coating biomimetic nanoparticles with chimeric antigen receptor T cell-membrane provides high specificity for hepatocellular carcinoma photothermal therapy treatment. Theranostics 2020, 10, 1281–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dong, M.; Chu, Y.; Zhou, L.; You, Y.; Pang, X.; Yang, S.; Zhang, L.; Chen, L.; Zhu, L.; et al. Dawn of CAR-T cell therapy in autoimmune diseases. Chin. Med. J. 2024, 137, 1140–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michels, K.R.; Sheih, A.; Hernandez, S.A.; Brandes, A.H.; Parrilla, D.; Irwin, B.; Perez, A.M.; Ting, H.A.; Nicolai, C.J.; Gervascio, T.; et al. Preclinical proof of concept for VivoVec, a lentiviral-based platform for in vivo CAR T-cell engineering. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e006292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, W.; Huang, B.; Xu, S.; Li, Y.; Zhu, L.; Yiqiao, H.; Wu, Z.; Wu, X. AAV-mediated in vivo CAR gene therapy for targeting human T-cell leukemia. Blood Cancer J. 2021, 11, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Shi, Y. Exosomes Derived from Immune Cells: The New Role of Tumor Immune Microenvironment and Tumor Therapy. Int. J. Nanomed. 2022, 17, 6527–6550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, W.; Lei, C.; Liu, S.; Cui, Y.; Wang, C.; Qian, K.; Li, T.; Shen, Y.; Fan, X.; Lin, F.; et al. CAR exosomes derived from effector CAR-T cells have potent antitumour effects and low toxicity. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storci, G.; De Felice, F.; Ricci, F.; Santi, S.; Messelodi, D.; Bertuccio, S.N.; Laprovitera, N.; Dicataldo, M.; Rossini, L.; De Matteis, S.; et al. CAR+ extracellular vesicles predict ICANS in patients with B cell lymphomas treated with CD19-directed CAR T cells. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 134, e173096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitt, J.M.; André, F.; Amigorena, S.; Soria, J.C.; Eggermont, A.; Kroemer, G.; Zitvogel, L. Dendritic cell-derived exosomes for cancer therapy. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 1224–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.H.; Peng, L.L.; Chen, Y.F.; Xu, Y.; Moradi, V. Focusing on exosomes to overcome the existing bottlenecks of CAR—T cell therapy. Inflamm. Regen. 2024, 44, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muntasell, A.; Berger, A.C.; Roche, P.A. T cell-induced secretion of MHC class II–peptide complexes on B cell exosomes. EMBO J. 2007, 26, 4263–4272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, T.; Cheng, L.; Zhou, C.; Zhao, Y.; Hu, Z.; Wu, X. In-Vivo Induced CAR-T Cell for the Potential Breakthrough to Overcome the Barriers of Current CAR-T Cell Therapy. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 809754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendell, J.R.; Al-Zaidy, S.A.; Rodino-Klapac, L.R.; Goodspeed, K.; Gray, S.J.; Kay, C.N.; Boye, S.L.; Boye, S.E.; George, L.A.; Salabarria, S.; et al. Current Clinical Applications of In Vivo Gene Therapy with AAVs. Mol. Ther. 2021, 29, 464–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachanov, A.; Kostyusheva, A.; Brezgin, S.; Karandashov, I.; Ponomareva, N.; Tikhonov, A.; Lukashev, A.; Pokrovsky, V.; Zamyatnin, A.A.J.; Parodi, A.; et al. The menace of severe adverse events and deaths associated with viral gene therapy and its potential solution. Med. Res. Rev. 2024, 44, 2112–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yudaeva, A.; Kostyusheva, A.; Kachanov, A.; Brezgin, S.; Ponomareva, N.; Parodi, A.; Pokrovsky, V.S.; Lukashev, A.; Chulanov, V.; Kostyushev, D. Clinical and Translational Landscape of Viral Gene Therapies. Cells 2024, 13, 1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brezgin, S.; Parodi, A.; Kostyusheva, A.; Ponomareva, N.; Lukashev, A.; Sokolova, D.; Pokrovsky, V.S.; Slatinskaya, O.; Maksimov, G.; Zamyatnin, A.A., Jr. Technological aspects of manufacturing and analytical control of biological nanoparticles. Biotechnol. Adv. 2023, 64, 108122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghilardi, G.; Fraietta, J.A.; Gerson, J.N.; Van Deerlin, V.M.; Morrissette, J.J.D.; Caponetti, G.C.; Paruzzo, L.; Harris, J.C.; Chong, E.A.; Susanibar Adaniya, S.P.; et al. T cell lymphoma and secondary primary malignancy risk after commercial CAR T cell therapy. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 984–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruella, M.; Xu, J.; Barrett, D.M.; Fraietta, J.A.; Reich, T.J.; Ambrose, D.E.; Klichinsky, M.; Shestova, O.; Patel, P.R.; Kulikovskaya, I.; et al. Induction of resistance to chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy by transduction of a single leukemic B cell. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1499–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardi, N.; Tuyishime, S.; Muramatsu, H.; Kariko, K.; Mui, B.L.; Tam, Y.K.; Madden, T.D.; Hope, M.J.; Weissman, D. Expression kinetics of nucleoside-modified mRNA delivered in lipid nanoparticles to mice by various routes. J. Control. Release 2015, 217, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesselhoeft, R.A.; Kowalski, P.S.; Anderson, D.G. Engineering circular RNA for potent and stable translation in eukaryotic cells. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Liu, Z.; Chen, S.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Wang, X.; Yang, F.; Wang, S.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; et al. Engineered circular RNA-based DLL3-targeted CAR-T therapy for small cell lung cancer. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2025, 14, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lin, L.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Yin, J.; Gao, F.; Liao, X.; Zhang, C.; Yin, Q.; Zhao, C.; et al. Synergically enhanced anti-tumor immunity of in vivo CAR by circRNA vaccine boosting. bioRxiv 2024. bioRxiv: 2024.07.05.600312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Xu, Y.; Li, J.; Gu, S.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y. The potential and challenges of circular RNA in the development of vaccines and drugs for emerging infectious diseases. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2025, 36, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostyusheva, A.; Brezgin, S.; Ponomareva, N.; Frolova, A.; Lunin, A.; Bayurova, E.; Tikhonov, A.; Slatinskaya, O.; Demina, P.; Kachanov, A. Biologics-based technologies for highly efficient and targeted RNA delivery. Mol. Ther. 2025, 33, 168–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayamajhi, S.; Nguyen, T.D.T.; Marasini, R.; Aryal, S. Macrophage-derived exosome-mimetic hybrid vesicles for tumor targeted drug delivery. Acta Biomater. 2019, 94, 482–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Wu, J.; Gu, W.; Huang, Y.; Tong, Z.; Huang, L.; Tan, J. Exosome-Liposome Hybrid Nanoparticles Deliver CRISPR/Cas9 System in MSCs. Adv. Sci. 2018, 5, 1700611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; He, D.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Ru, D.; Wang, L.; Gong, K.; Liu, F.; Duan, Y.; Li, H. Exosome-liposome hybrid nanoparticle codelivery of TP and miR497 conspicuously overcomes chemoresistant ovarian cancer. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 20, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, W.; Zhu, T.; Tang, L.; Li, Z.; Jiang, G.; Huang, X. Inhalable CAR-T cell-derived exosomes as paclitaxel carriers for treating lung cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolesova, E.; Pulone, S.; Kostyushev, D.; Tasciotti, E. CRISPR/Cas bioimaging: From whole body biodistribution to single-cell dynamics. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2025, 224, 115619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.I.; Park, J.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, X.; Han, Y.; Zhang, D. Recent advances in extracellular vesicles for therapeutic cargo delivery. Exp. Mol. Med. 2024, 56, 836–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Li, D.; Pan, X.; Liang, Y. Targeted therapy using engineered extracellular vesicles: Principles and strategies for membrane modification. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyquem, J.; Mansilla-Soto, J.; Giavridis, T.; van der Stegen, S.J.C.; Hamieh, M.; Cunanan, K.M.; Odak, A.; Gönen, M.; Sadelain, M. Targeting a CAR to the TRAC locus with CRISPR/Cas9 enhances tumour rejection. Nature 2017, 543, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, L.; Holt, R.A.; Cullis, P.R.; Evgin, L. Direct in vivo CAR T cell engineering. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2024, 45, 406–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Pan, H.; Li, W.; Chen, Z.; Ma, A.; Yin, T.; Liang, R.; Chen, F.; Ma, Y.; Jin, Y.; et al. T Cell Membrane Mimicking Nanoparticles with Bioorthogonal Targeting and Immune Recognition for Enhanced Photothermal Therapy. Adv. Sci. 2019, 6, 1900251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Meng, F.; Li, X.; Xue, L.; Chen, A.; Qiu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, L.; Liu, F.; Li, Y.; et al. Nanomodified Switch Induced Precise and Moderate Activation of CAR-T Cells for Solid Tumors. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2205044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterner, R.C.; Sterner, R.M. CAR-T cell therapy: Current limitations and potential strategies. Blood Cancer J. 2021, 11, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.; Eslami, M.; Sahandi-Zangabad, P.; Mirab, F.; Farajisafiloo, N.; Shafaei, Z.; Ghosh, D.; Bozorgomid, M.; Dashkhaneh, F.; Hamblin, M.R. pH-Sensitive stimulus-responsive nanocarriers for targeted delivery of therapeutic agents. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2016, 8, 696–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakar, M.S.; Kearl, T.J.; Malarkannan, S. Controlling Cytokine Release Syndrome to Harness the Full Potential of CAR-Based Cellular Therapy. Front. Oncol. 2020, 9, 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Han, J.; Gong, Y.; Liu, C.; Yu, H.; Xie, N. Nanoparticle-Based Drug Delivery Systems Targeting Tumor Microenvironment for Cancer Immunotherapy Resistance: Current Advances and Applications. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parodi, A.; Molinaro, R.; Sushnitha, M.; Evangelopoulos, M.; Martinez, J.O.; Arrighetti, N.; Corbo, C.; Tasciotti, E. Bio-inspired engineering of cell- and virus-like nanoparticles for drug delivery. Biomaterials 2017, 147, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, J.-G.; Wang, L.; Gao, F.; You, Y.-Z.; Xiong, Y.; Yang, L. Erythrocyte membrane is an alternative coating to polyethylene glycol for prolonging the circulation lifetime of gold nanocages for photothermal therapy. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 10414–10425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Lila, A.S.; Ishida, T. Liposomal Delivery Systems: Design Optimization and Current Applications. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2017, 40, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awasthi, R.; Maier, H.J.; Zhang, J.; Lim, S. Kymriah® (tisagenlecleucel)—An overview of the clinical development journey of the first approved CAR-T therapy. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2023, 19, 2210046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, B.D.; Ghobadi, A.; Oluwole, O.O.; Logan, A.C.; Boissel, N.; Cassaday, R.D.; Leguay, T.; Bishop, M.R.; Topp, M.S.; Tzachanis, D.; et al. KTE-X19 for relapsed or refractory adult B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: Phase 2 results of the single-arm, open-label, multicentre ZUMA-3 study. Lancet 2021, 398, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlDallal, S.M. Yescarta: A New Era for Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Patients. Cureus 2020, 12, e11504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Xia, C.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, N.; Chen, Z.; Li, W. Research Progress on Cell Membrane-Coated Biomimetic Delivery Systems. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 772522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Generation | Intracellular Domains | The Principle of Operation | Advantages | Disadvantages | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | CD3ζ | Provides only activation signal 1 (via ITAM motives). | Simplicity of construction. | Insufficient proliferation, rapid cell death in vivo, and low efficiency. | [18,19,20] |

| Second | CD3ζ + one co-stimulatory domain (CD28, 4-1BB, etc.) | Provides signal 1 (activation) and signal 2 (co-stimulation). | Rapid activation, proliferation, and long-term persistence of cells. | Risk of cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurological toxicity (ICANS) | [18,19,20] |

| Third | CD3ζ + two co-stimulatory domains (e.g., CD28 + 4-1BB) | An amplified and prolonged activation signal. | A potentially more powerful response. | Increased risk of depletion of T cells, lack of clear advantages over the 2nd generation in the clinic. | [19,20] |

| Fourth | Multidomain constructs + additional gene cassettes (e.g., cytokines, induced promoters). | Targeted delivery of immunomodulators to the tumor microenvironment or logical activation (AND-gate). | High safety (reduction in on-target/off-tumor toxicity), overcoming the immunosuppressive microenvironment. | High complexity of design and production, and potential immunogenicity of the structure. | [19,20] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tkachenko, E.; Ponomareva, N.; Evmenov, K.; Kachanov, A.; Brezgin, S.; Kostyusheva, A.; Chulanov, V.; Volchkova, E.; Lukashev, A.; Kostyushev, D.; et al. CAR Therapies: Ex Vivo and In Vivo Potential of Exosomes and Biomimetic Nanoparticles. Cancers 2025, 17, 3766. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233766

Tkachenko E, Ponomareva N, Evmenov K, Kachanov A, Brezgin S, Kostyusheva A, Chulanov V, Volchkova E, Lukashev A, Kostyushev D, et al. CAR Therapies: Ex Vivo and In Vivo Potential of Exosomes and Biomimetic Nanoparticles. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3766. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233766

Chicago/Turabian StyleTkachenko, Ekaterina, Natalia Ponomareva, Konstantin Evmenov, Artyom Kachanov, Sergey Brezgin, Anastasiya Kostyusheva, Vladimir Chulanov, Elena Volchkova, Alexander Lukashev, Dmitry Kostyushev, and et al. 2025. "CAR Therapies: Ex Vivo and In Vivo Potential of Exosomes and Biomimetic Nanoparticles" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3766. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233766

APA StyleTkachenko, E., Ponomareva, N., Evmenov, K., Kachanov, A., Brezgin, S., Kostyusheva, A., Chulanov, V., Volchkova, E., Lukashev, A., Kostyushev, D., & Timashev, P. (2025). CAR Therapies: Ex Vivo and In Vivo Potential of Exosomes and Biomimetic Nanoparticles. Cancers, 17(23), 3766. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233766